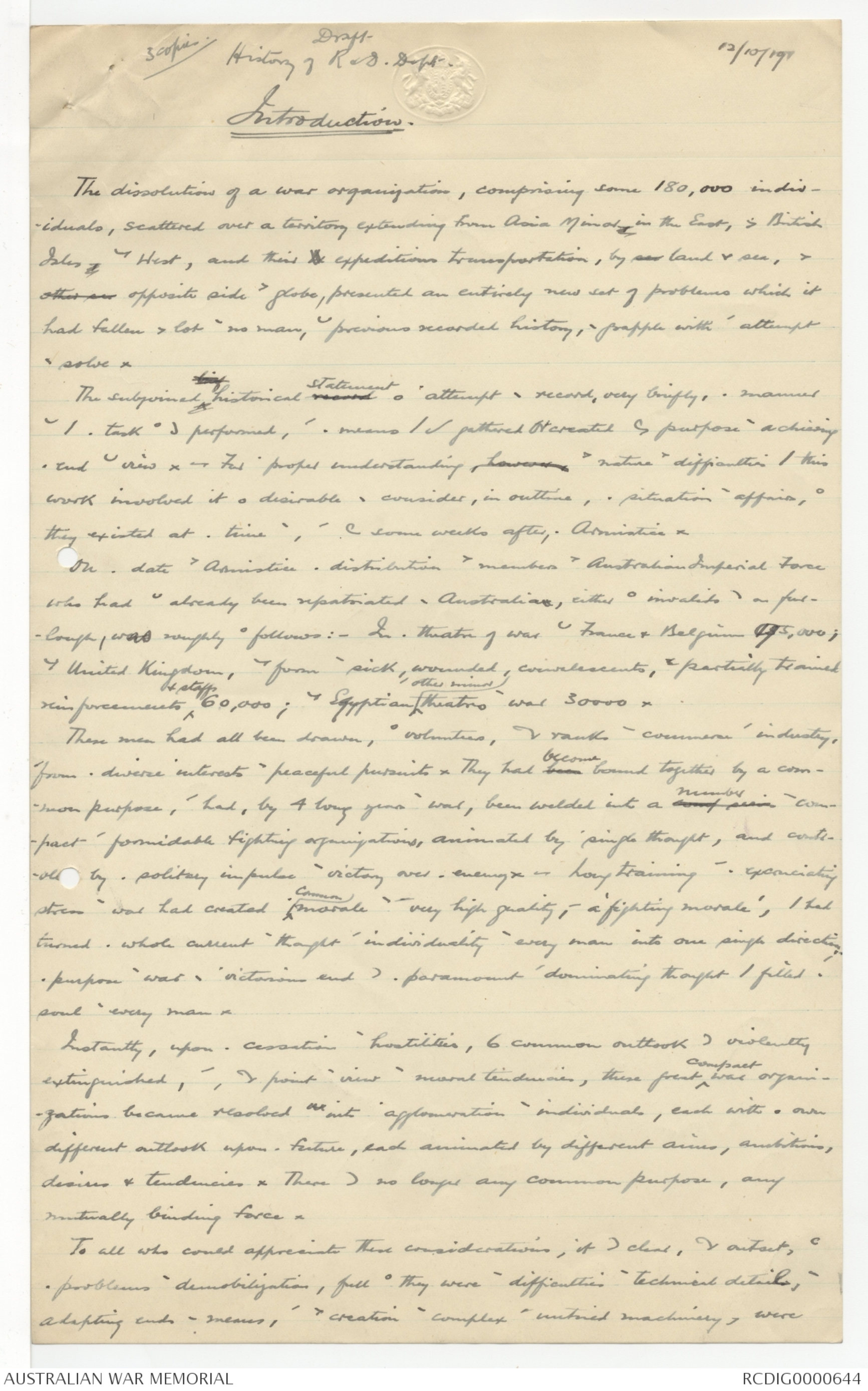

General Sir John Monash, Personal Files Book 23, 24 September - 26 December 1919, Part 2

(3 copies)

Draft

History of R & D Dept

12/10/19

Introduction

The dissolution of a war organization, comprising some 180,000 individuals,

scattered over a territory extending from Asia Minor in the East, & British

Isles in the West, and their xx expeditious transportation, by sea land & sea, &other in opposite side of the globe, presented an entirely new set of problems which it

had fallen to the lot of no man, in previous recorded history, to grapple with and attempt

to solve.

The subjoined ^brief historical record statement is an attempt to record, very briefly, the manner

in which the task has been performed, and the means which we gathered or created for the purpose of achieving

the end in view. - For a proper understanding, however of the nature of the difficulties which this

work involved it is desirable to consider, in outline, the situation of affairs, as

they existed at Fthe and, for some weeks after the Armistice.

On the date of the Armistice the distribution of members Australian Imperial Force

who had not already been repatriated to Australia, either as invalids or on furlough,

was roughly follows:- In the theatre of war in France & Belgium 95,000;

in the United Kingdom, in the form of sick, wounded, convalescents, & partially trained

reinforcements ^& staffs 60,000; in the Egyptian ^and other minor theatres of war 30000.

These men had all been drawn, as volunteers, from the ranks of commerce & industry,

and from the diverse interests of peaceful pursuits. They had been become bound together by a common

purpose, and had, by 4 long years of war, been welded into a xxx xxx number of compact

and formidable fighting organizations, animated by single thought, and controlled

by the solitary impulse of victory over the enemy. - Long training and the excruciating

stress of war had created ^a common morale of very high quality, and a 'fighting morale' which had

turned the whole current thought and individuality of every man into one single direction.

The purpose of war to a victorious end was the paramount and dominating thought which filled the

soul of every man.

Instantly, upon the cessation of hostilities, this common outlook was violently

extinguished, and, from the point of view of moral tendencies, these great ^compact war organizations

became resolved into an agglomeration of individuals, each with his own

different outlook upon the future, each animated by different aims, ambitions,

desires and tendencies. There was no longer any common purpose, any

mutually binding force.

To all who could appreciate these considerations, it was clear, from the outset, that

the problems of demobilization, full as they were of difficulties of technical details, of

shifting ends and means, and of the creation of complex and untried machinery, were

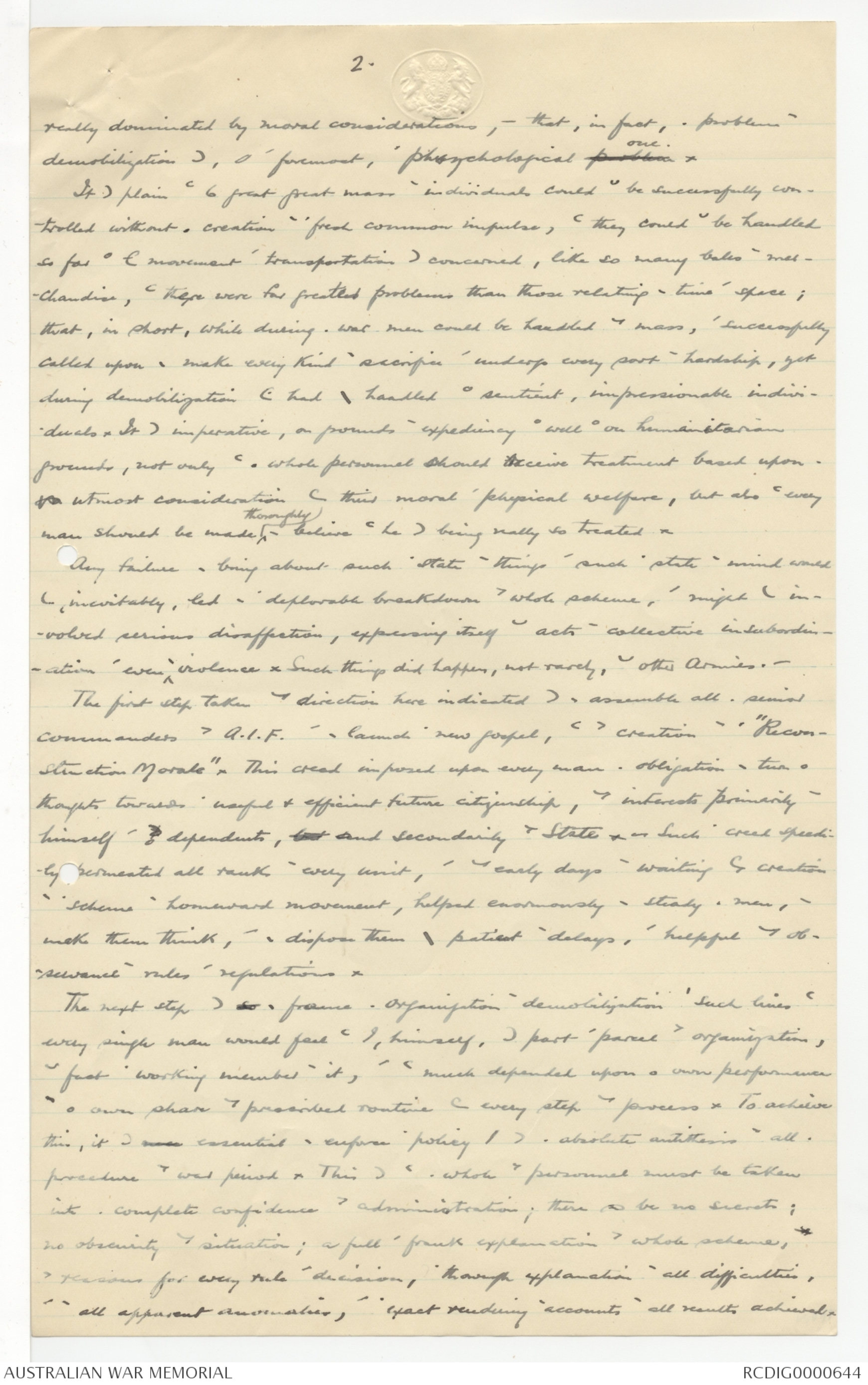

2

really dominated by moral considerations, - that, in fact, the problem of

demobilization was, first and foremost, a psychological problem one.

It was plain that this great great mass of individuals could not be successfully controlled

without creation of a fresh common impulse, that they could not be handled

so far as (movement transportation was concerned, like so many bales of merchandise,

that there were far greater problems than those relating to time and space;

that, in short, while during war men could be handled in the mass, and successfully

called upon to make every kind of sacrifice and undergo every post of hardship, yet

during demobilization they had to be handled as sentient, impressionable individuals.

It was imperative, on grounds of expediency as well as on humanitarian

grounds, not only that whole personnel should receive treatment based upon thexx utmost consideration for their moral and physical welfare, but also that every

man should be made ^thoroughly to believe he was being really so treated.

Any failure to bring about such a state of things and such state of mind would

have inevitably, led to a deplorable breakdown of the whole scheme, and might have involved

serous dissatisfaction, expressing itself in acts of collective insubordination

even and ^of violence. Such things did happen, not rarely,in other Armies. -

The first step taken in the direction here indicated was to assemble all the senior

commanders of the A.I.F. and to launch a new project, with all the creation of a "Reconstruction

Morale". This creed imposed upon every man the obligation to turn his

thoughts towards a useful & efficient future citizenship, in the interests primarily of

himself and h dependents, but and secondarily of the State. -Such a creed specially

permeated all ranks of every unit, and in the early days of waiting for the creation

of a scheme of homeward movement, helped enormously to steady men, to

make them think, and to dispose them to be patient of delays, and helpful in the observance

of rules and regulations.

The next step was to do form an organization of demobilization on such lines that

every single man would feel that he, himself, was part and parcel of the organization,

in fact a working member of it, and that much depended upon his own performance

and his own share of the prescribed routine for every step in the process. To achieve

this, it was essential to enforce a policy which was the absolute antithesis of all the

procedure of the war period. This was that the whole personnel must be taken

into the complete confidence of the administration; there can be no secrets;

no obscurity in the situation; a full and frank explanation of the whole scheme,*

of the reasons for every rule and decision, a thorough explanation of all difficulties,

and of all apparent anomalies, and an exact rendering of accounts of all results achieved.

3

The methods by which these purposes were achieved consisted in propagandaby partly by the wide promulgation among all ranks of pamphlets

leaflets, news sheets, bulletins and notices of all kinds, and partly by vocal

addresses ^delivered at many stages of the journey by numerous specially selected officers and men, who

could talk to the soldiers, both from the platform and in small groups, who could

glean a man's point of view and could sympathetically explain apparent

difficulties or anomalies, ^and show why ^some strongly desired amendment of the

regulations we had cause have ^disadvantage more men than xxxxx it might benefit

Above all, it was put to the men quite plainly, that speedy movement, and physical

comfort ^during the movement and in depôts depended upon that same characteristic of "successful team

work" which had helped them while I had a hand to connect them on the field these had again to win great battles. They were taught that this scheme of

demobilization was also going to be a great battle against unprecedented

difficulties, and that the whole A.I.F. must pull together as one man, if they

were to get home quickly, comfortably, and in the right frame of mind.

It is not an easy matter to inspire 180,000 in individual ^men with a common

outlook and a uniform code of thought. It reflects the highest credit upon

the enthusiasm, skill and loyalty of all subordinate commanders that this

task was so speedily, with effectually and successfully carried out.

From the moment that the responsibility of organizing the Australian Demobilization

was imposed upon me by the Commonwealth Prime Minister, on Nov 21/1918, I found

myself comforted with a number of grave questions of fundamental importance.

At what rate should the process be effected, whether at the maximum possible rate

was the same lessor rate? Would the shipping situation, in any case, reach possiblexxxxx high rate of movement? On what principle should the priority of right to

speedy repatriation be determined? Could any time be gained by using

French ports for final embarkation of the Field Army in France? What should be

done with the many thousands of men who were doomed in any case to wait

many months for the ships which would carry them home? Where should I find a

body of efficient and loyal helpers to carry out the details of this stupendous task? How

best could I deal xx to with a situation of general demoralization of all public services

which was the outcome of the weariness of four year's of war and which manifested itself

in every direction?

There were also many subordinate questions. Peace negotiations had not yet

been begun, and it was quite uncertain at what rate troops actually in the field

in France, Belgium & Egypt could be released by. the War office from further service.

All French & British posts were congested. The French railways were in a

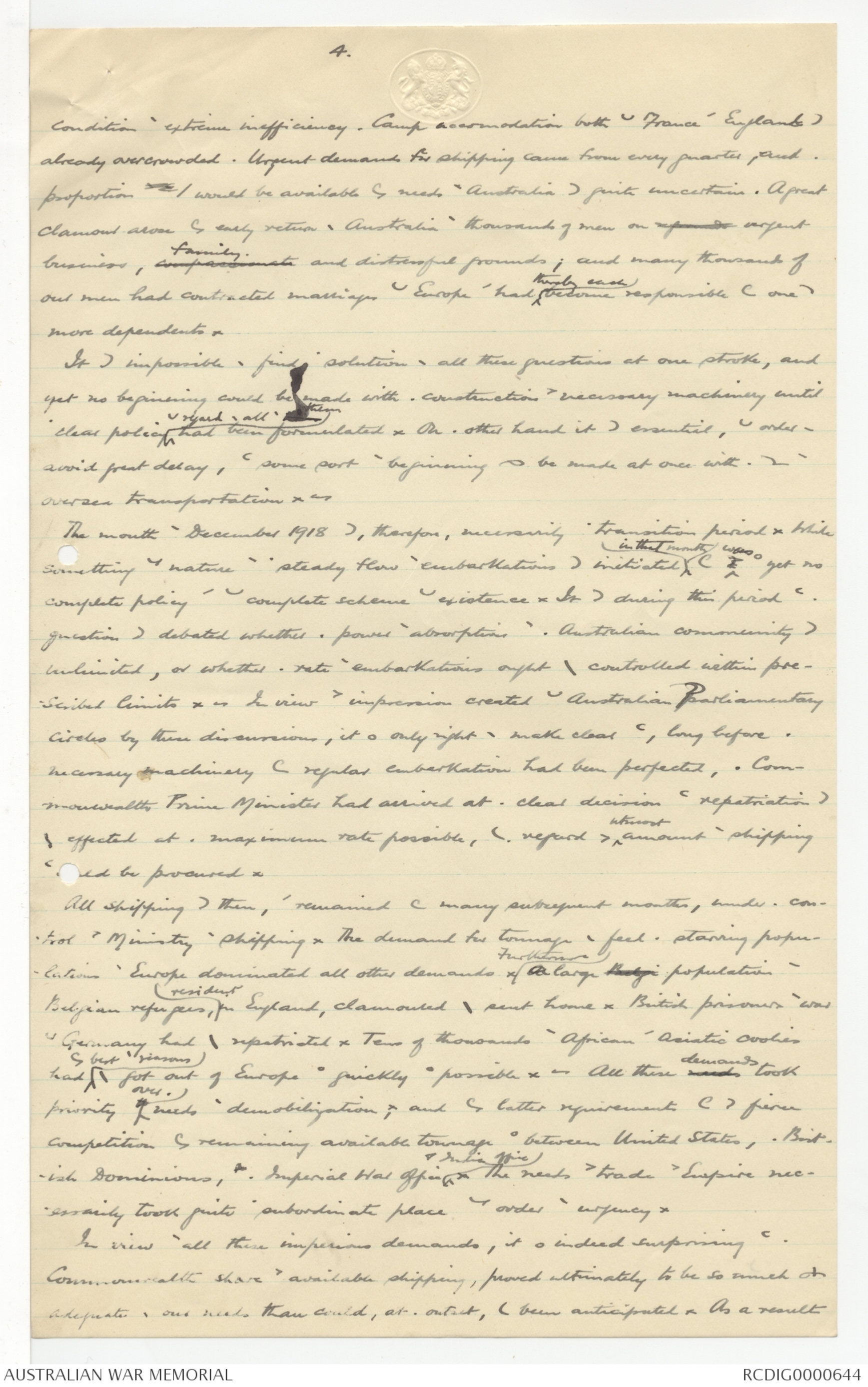

4.

condition of extreme in efficiency. Camp accomodation both in France & England was

already overcrowded. Urgent demands for shipping came from every quarter, and the

proportion xx which would be available for the needs of Australia was quite uncertain. A great

clamour arose for the early return to Australia of thousands of men on refxxx urgent

business, compassionate family and distressful grounds; and many thousands of

our men had contracted marriages in Europe and had ^thereby each become responsible for one or

more dependents.

It was impossible to find a solution to all these question at one stroke, and

yet no beginning could be made with the construction of the necessary machinery until

a clear policy ^in regard to all of them had been formulated. On the other hand it was essential, in order to

avoid great delay, that some sort of beginning must be made at once with the scheme of

oversea transportation. -

The month of December 1918 was, therefore, necessarily a transition period. While

in that month was

something in the nature of a steady flow of embarkations was initiated ^in that month there was as yet no

complete policy and no complete scheme in existence. It was during this period that the

question was debated whether the power of absorption of the Australian community was

unlimited, or whether the rate of embarkations ought to be controlled within prescribed

limits. - In view of the impression created in Australian Parliamentary

circles by these discussions, it is only right to make clear that, long before the

necessary machinery for regular embarkation had been perfected,. Commonwealth

Prime Minister had arrived a the clear decision that repatriation was

to be

expected at the maximum rate possible, having regard to the ^utmost amount of shipping

that could be provided.

All shipping was then, and remained for many subsequent months, under control

of the Ministry of shipping. The demand for tonnage to feed the starving populations

of Europe dominated all other demands. ^Furthermore a large Belg population of

Belgian refugees, ^resident in England, clamoured to be sent home. British prisoners of war

in Germany had to be repatriated. Tens of thousands of African and Asiatic coolies

had ^for the best of reasons got out of Europe as quickly as possible. - All these needs demands took

priority ^over the needs of demobilization; and for the latter requirements there was fierce

competition for the remaining available tonnage as between United States, the British

Dominions, and the Imperial War Office ^and India Office. The needs of the trade of the Empire necessarily

took quite a subordinate place in the order of urgency.

In view of all these imperious demands, it is indeed surprising that the

Commonwealth share of the available shipping, proved ultimately to be so much someday

adequate to our needs than could, at the outset, have been anticipated. As a result

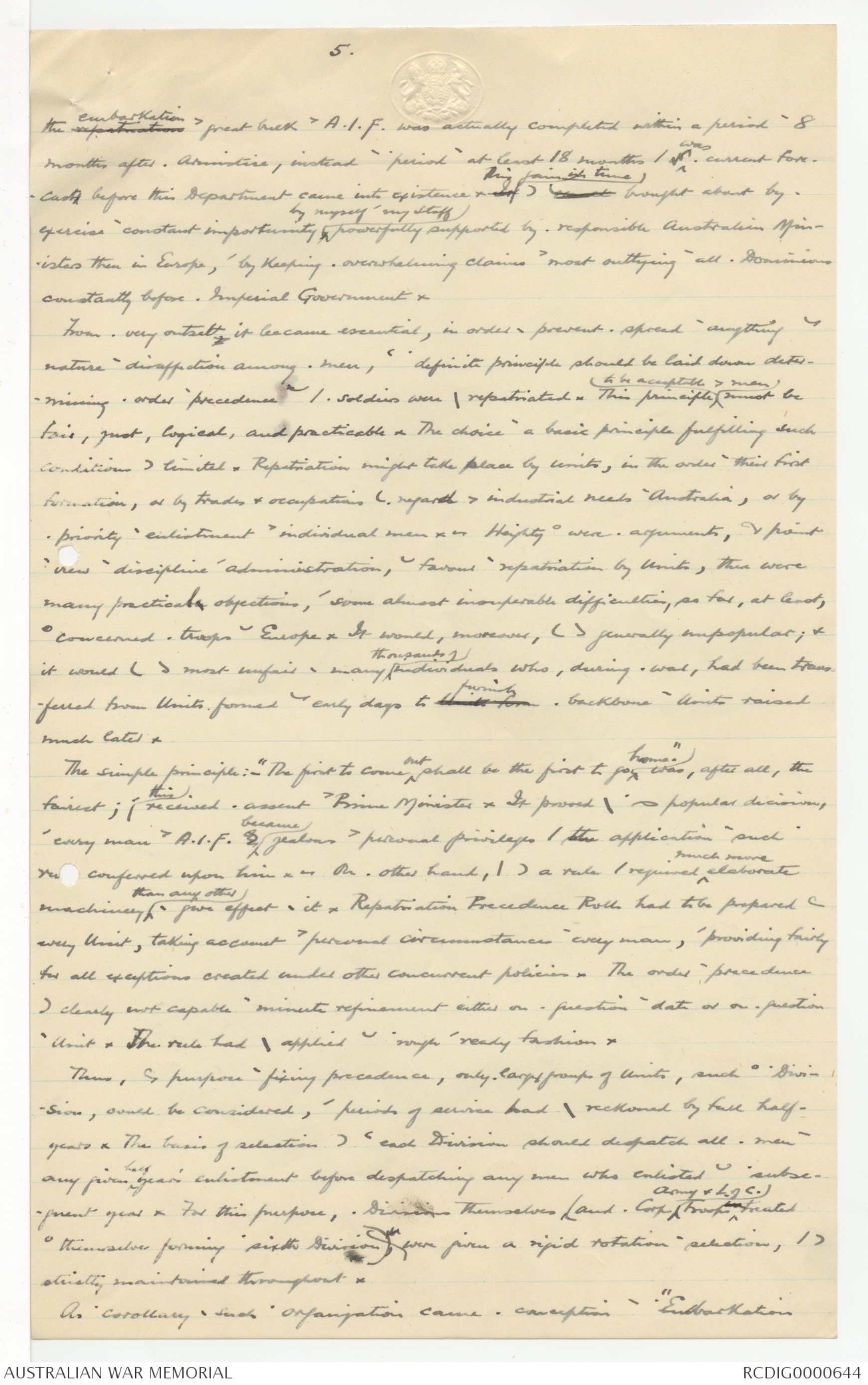

5.

the expatriations embarkation of the great bulk of the A.I.F. was actually completed with a period of 8

months after the Armistice, instead of a period of at least 18 months which was current forecast

before this Department came into existence. ^This gain in time xxxx brought about by the

exercise of constant importunity ^by myself and my staff powerfully supported by the responsible Australian Ministers

then in Europe, and by keeping the overwhelming claims of the most outlying all Dominions the Dominions

constantly before the Imperial Government.

From the very outset it became essential, in order to prevent the spread of anything in the

nature of disaffection among the men, that a definite principle should be laid down determining

the order of precedence in which the soldiers were repatriated. This principle ^to be acceptable to the men must be

fair, just, logical, and practicable. The choice of a basic principle fulfilling such

conditions was limited. Repatriation might take place by units, in the order of their first

formation, or by trades & occupations having regard to the industrial needs of Australia, or by

the priority of enlistment of the individual man. - Mighty as were the arguments, from the

of view of discipline and administration, in favour of repatriation by Units, there were

many practical objections, and some almost inoperable difficulties, so far, at least,

as concerned the troops in Europe. It would, moreover, have been generally unpopular; &

it would have been most unfair to many ^thousands from Individuals who, during the war, had been transferred

from Units formed in the early days to think form provide the backbone of Units raised

much later.

The simple principle:- "The first to come ^out shall be the first to go ^home." was, after all, the

fairest; ^and this received the assent of the Prime Minister.It proved to be a most popular decision,

and every man of the A.I.F. x ^became jealous of the personal privileges which the application of such a

conferred upon him. On the other hand, it was a rule which required ^much more elaborate

machinery ^than any other to give effect to it. Repatriation Precedence Rolls had to be prepared for

every Unit, taking account of the personal circumstances of every man, and providing fairly

for all exceptions created under other concurrent policies. The order of precedence

was clearly not capable of minute refinement either on a question of date or on a question

of Unit. The rule had to be applied in a rough & ready fashion.

Thus, for the purpose of fixing precedence, only, large groups of Units, such as a Division,

would be considered, and periods of service had to be reckoned by full half-years.

The basis of selection was that each Division should despatch all the men of

any given ^half year's enlistment before despatching any men who enlisted in a subsequent

year. For this purpose, the Divisions / themselves and the Corp Army and each of their Troops treated

as themselves forming a sixth Division were given a rigid rotation of selection, which was

strictly maintained throughout.

As a corollary of such an organization came the conception of a "Embarkation

6

Quota", to be provided by each Division in turn. This was fixed at the constant strength

of 1000 men, being the average load of a railway train, the average load for a transport,

& the average accomodation of a normal camp. It was a close analogy to an Infantry

Battalion. - In order that a sense of cohesion and discipline should be maintained

during a period of some four months that the Quota would have to exist and an organized

body, each Quota was designed, complete in all details except horse transport,

in lines of an xxxx Infantry Battalion, fully officered staffed by personnel under

whom the men had been accustomed to serve in the field.

Such a procedure applied only to the field Army in France. It did not apply to the

population of some 40000 invalids and convalescents who found themselves in

England on the signing of Armistice, and it did not apply to the field force in Egypt and Palestine.

In the latter case, repatriation by Units was found better to suit the local

conditions and the military situation in that theatre of war.

It was also very important, to determine from the outsets whether any, or many,

embarkations could be effected, direct to Australia from French ports. A short

investigation proved that such a prospect was utterly impracticable. On the one hand

neither were ^suitable ports available, nor depôts to house the troops, nor trains to carry them

to such ports as would, if available, have been suitable, nor an organization to

administer such a line of movement. - On the other hand there was already in

40000 troops at any one time, and there was also in existence quite a machinery of movement.

from England to France in port of Havre, which machinery was capable of

reversal so as to be available to function in the opposite direction.

Moreover. the Prime Minister laid down that every man was to receive thee weeks

holiday in England before embarkation. The resources of cross-channel shipping

would not have been equal to dealing with such a large stream of men from

France to England for leave, and then back to France for embarkation. to Australia

All transportation facilities were already taxed to their uttermost by British

and American demobilization. -

I was able therefore to arrive at the decision, early in January ^1919, that all final

embarkations must take place from British ports. This had a further advantage

of giving me direct access to & close supervision of the shipping allocated to me, and to

ensure the adequate standard of comfort in the equipment and the rationing of all the

ships. No equally effective control could have been retained over shipping in

foreign ports, under the control of foreign port authorities.

7

Under the most expeditious scheme of repatriation that could be devised, it was imitable

that many thousands of the men would be compelled to remain in Europe for

many months. It was imperative to devise means to employ them ^as usefully as

possible. This policy was also inspired by the Prime Minister, and he authorized the promulgation

of liberal terms in order to encourage applicants. From this inspiration

sprang my scheme of Non-Military Employment, which was a considerable

extension of the A.I.F. Education scheme, already in partial existence

when this Department began to operate, and which I took over in its entirety. The

whole story of the Non-Military Employment Branch of this Department is told

briefly in Chapter ?

For the first two months, i.e. Dec 1918 & Jany 1919, my principal difficulties

arose from the entire lack of administrative facilities of any sort or kind. The

condition of general demobilization was, from the business man's point of view,

appalling. Postal, telegraph and telegraph services were slow and unreliable; all

means of transportation was seriously congested, making travel & movement

of troops ^& current staff officers tedious and difficult. Qualified Staff officers were still with their Brigades

and Divisions in the field, and their fighting services might again have been required. It was a

slow and laborious process to collect a competent personnel, and to construct ever

the mere administrative machinery of the Departmental London Headquarters.

In addition Embarkation staffs at French & English ports had to be created, and the Australian

depôts in Havre & on Salisbury Plains had to be reorganised in order to be in

a position both to reverse their previous functions, and to deal, with precision

and regularity, with a steady stream of Quotas travelling from east to west.

It was essential to make use, as far as possible, existing A.I.F. facilities, &

so, such ^existing branches as 'pay', 'central registry,' records &c &c were drawn ^into service, &

arrangement with the A.I.F. Administrative Commandant, was considered as

an integral part of this Department, while still carrying out their former duties.

Indeed the close association of the Administrative and Demobilization xxxxx Departments of the A.I.F.

and the cordial and sympathetic cooperation of their respective staffs was the Keynote of

much of the success, and also of the ^financial economy, achieved.

In the following Chapter an effort has been made to place on permanent

record, an outline narrative of the activities of the Department during the 10 months

of its existence as a separate organization. They will disclose in more detail the

nature of the methods employed to carry the policies which they have been indicated. - The whole

of the policy machinery for its realizations were embodied in a series of orders which

we called "General Instructions". These were issued [[sectionally?]] to the whole of the A.I.F.

8

Europe and the East, and comprise in themselves a consecutive and complete narrative of the

steps by which the operation of the Department were controlled. Sw The experience of space

has precluded the publication of the whole of these General Instructions in this

Report, but a substantial portion of them has been reproduced as an Appendix, and

will repay perusal by those who are desirous of familiarizing themselves with

the details of the whole process of the Australian Demobilization.

In closing these introductory remarks to the formal report to the short first& nevertheless Department of Repatriation and Demobilization of the A.I.F., which

had a comparatively short but a most strenuous life, I cannot refrain

from tendering sincere acknowledgements the a band of loyal helpers, who

were prepared, at great personal sacrifice, to continue, for nearly another

year, their arduous war service to Australia and to the A.I.F.

Brig. Gen Foott ^stayed functional throughout as my Deputy, and was charged with the

duty of carrying into practical effect all my orders and policies, and of coordinating

and supervising the scheme of the whole Demobilization staff. The heads

of the several branches of the Department were the following: - Col. Bonches [[titles?]]

controlled the branch dealing with Non-Military employment and ^with all Individual

questions ^of every kind advising in connection with the troops of all ranks. He was ably

assisted in the direction of educational and industrial activities by his brigadier

Generals McNicoll? & Long & by Lt Col Sanday WH DSO.MC. & Mr. Burchell M.H.R. -

Brigadier General EA Wisdom CB. CMG. DSO (?) was Director of Movements, Quartering

and Supply. All parties of Shipping, Depôts, Ports, Embarkations and the war

(principal?) welfare of the troops were under his direct control. The Administration

Branch of the Dept. was headed by Lt Col Ridley J.C.T D.S.O who was responsible

for the control of the staff and for all statistical and documentary business relating

to Demobilization. The Fourth Branch dealt with the demobilization

of all war equipment, stores and animals, and the acquisition of

all post-bellum Army equipment. This branch was organized and supervized

by Maj.Gen WA. Coxen, CB CMG DSO, assisted by Col(B.T?)Leane (?) CBE and

Major C Speckman MC. The last, but by no means the least

important Branch dealt with financial policy, pay, allowances, fees,

accounts, audit & expenditure in every detail. It was covered directed

first by Lt Col H Evans (CME), & later by Lt Col. T. J. Thomas ( )

The A.I.F. Depôts at Havre were under the control of Col. CH Davis, CBD. DSO. VD, while

those on Salisbury Plain, England were ^ably commanded successfully by

Maj-Gen Sir T.H. McCay [?) KCMB CB. VD and Maj Gen Sid C Rosenthal KCB CMG DSO

9.

Brigadier General J.P. McGlinn performed most valuable services as the Liaison

officer of the Department to the Depôts in United Kingdom, while Lt Col. J.L. Whitham CMG DSO

performed similar functions at G.H.Q. in France.

Towards the end of March 1919, the Hon the Minister of Defence, Senator ? G F

Pearce arrived in England, and his presence on the spot proved of inestimable value

to the scheme in hand. Not only was he able, by the weight of his authority, to obtain

prompt attention to the demands made upon Imperial resources in a direction of

maintaining our embarkation programmes at a full scale, but he could

settle ^without delay a great mass of administrative p and financial questions which were of a

nature to require the experience of Ministerial responsibility.

When xxxxx the whole of the A.I.F. in Egypt had been embarked, and the

residue remaining in England had, on Sep 30/19, fallen to about

10000 of all ranks, this Department was merged with that of the Administration Commandant, Brig -Gen Jess, & all officer service officers of the Repatn.

and Demobilization Dept. senior to him caused relinquished their

duties.

JM Monash

Lieut.General

Dir.G -R & D

DRAFT

13.10-19.

HISTORY OF REPATRIATION & DEMOBILISATION DEPT.

INTRODUCTION

The dissolution of a war organisation, comprising some

180,000 individuals, scattered over a territory extending from

Asia Minor in the Fast, to the British Isles in the West, and

their expeditious transportation, by land and sea, to the

opposite side of the globe, presented an entirely new set of

problems which it had fallen to the lot of no man, in previous

recorded history, to grapple with and attempt to solve.

The subjoined historical statement is an attempt to

record, very briefly, the manner in which the task has been

performed, and the means which we were gathered or created for the

purpose of achieving the end in view.- For a proper understanding

of the nature of the difficulties which this work involved

it is desirable to consider, in outline, the situation ofn

affairs, as they existed at the time of, and for some weeks

after, the Armistice.

on the date of the Armistice the distribution of the

members of the Australian Imperial Force who had not already been

repatriated to Australia, either as invalids or on furlough, was

roughly as follows: - In the theatre of war in France and

Belgium, 95,000; in the United Kingdom, in the form of sick,

wounded, convalescents, partially trained reinforcements and

staffs, 60,000, in the Egyptian and other minor theatres of

war. 30,000.

These men had all been drawn, as volunteers, from the

ranks of commerce and industry, and from the diverse interests

of peaceful pursuits. They had become bound together by a

common purpose, and had, by ^four 4 long years of war, been welded

into a number of compact and formidable fighting organisations,

animated by a single thought, and controlled by a solitary

impulse of victory ever the enemy. - Long training and the

Sam scott

Sam scottThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.