Sir John Monash, Personal Files Book 14, 6 October - 30 November 1916, Part 6

– 3 –.

everybody understands. A Commander generally has plenty of time

to go round to see the different units in the command and

ascertain that Officers and Non-Commissioned Officers know where

and when to go forward, and under what circumstances they will

co-operate with others, the time, place, and geographical features

of the operation, and everything concerned in connection

with it. Commanders should make a practice of doing this. Put

energy into your work, hard though ^you at present work. You will thus

have a very considerable guarantee for the success of your operation.

One thing avoid whenever possible. That is changes in

orders. It requires a nice judgement to balance the advantages,

and disadvantages, of the promulgation of particular orders as

to committing orders definitely on certain points. It may be

that after issuing a preliminary order you find that upon fuller

consideration you have made a mistake, that you have named the

wrong road, time, or unit. But make as little alteration as

possible. Every change of orders involves confusion, sometimes

little, sometimes much. But you will probably find the following

true--"Order, Counter-Order, Disorder". Orders when once issued

should never by modified, chopped or changed about on Active

Service unless absolutely necessary for the safe conduct of

the operation and men, then as little as is consistent with

that safety. Take the example of an operation ordered for

4 o'clock in the afternoon. The Infantry get into positions of

readiness, wires are laid, signal stations established, and

communication strengthened etc., etc. Then orders are received

that the operation is put on for half an hour. Probably some of

the subordinate Units have already started. Wires are overcrowded

with signal traffic, and everybody gets rattled and confused

just at a moment when he should be most cool and collected. At

the first attack on Hill 60, orders had to be altered only

because at the last moment the Artillery authorities decided

that certain batteries would not be available, and could not be

supplied to assist the Infantry, as it would take two days to

fix and wires. Consequently Commanders did not know what was

going to happen, and the whole operation was more or less,

though not entirely, a failure. And simply because a change of

orders had been made when everybody was thoroughly settled on

a certain plan of campaign which had to be altered in a hurry.

It would have been far better to have said nothing about the

Artillery, and let the operation go ahead. They should have

assumed that the batteries would co-operate, and said nothing

about the change. The orders were altered, everybody got rattled,

everybody waited, it was altogether a mis-timed, mis-calculated,

and mis-directed operation. The result was considerable loss of

life and little gain. Later on all xthese errors were eliminated

and the attack was more of a success.

I will now deal with alterations in orders. This is

a subject under your own control, and you have the power to

perfect it with your own units. It is better to carry one an

operation on lines which are maturer lines, though not the very

best, than to alter orders for trifling reasons. I do not mean

to say for one moment "right, or wrong, you stick to an order;"

But think twice, and think long, before altering orders for

trifling reasons. It means stress on the personnel. It always

hits the man in the ranks. He is awakened up in the middle of

the night, dragged away from his meals, not allowed to get a

clean, either because of miscarriage or misdirection of orders

from above; men are thus deprived of their rest, their food, and

their comfort. And very often all for nothing. It is seen even

in a peace training camp. Take for example a fatigue party has

to report at a certain time. The men are warned. The party marches

off. The somebody says "we we will take that party out of "B" Company,

not "A" Company". A counter-order is issued and it is a

case of "back to your quarters". It means another party have then

to go through the trouble of preparation, and finally arrives

late. Two sets of men have been bucketered about instead of one.

The point is that owing to ill-considered orders in changing, it

invariably means stress upon the personnel and consequently a

reduction of their fighting efficiency.

– 4 –.

I said a word about framing orders. But I said

very little about reading of orders. Always enjoin upon your

subordinate Officers the necessity of careful reading of orders.

Every formation publishes orders. Army Orders, Corps, Divisions,

Brigades, Battalions; and Officers are overwhelmed with orders,

and they are very much inclined to say "they cannot expect us to

read all this stuff. I won't take any notice of it". It is a

dangerous state of mind to get into. Any minute an order may be

of extreme importance, whether an administrative, or a fighting

order. Every order should be read on its merits, and scrutinised

carefully as to whether it does affect you or not. For instance,

you get an order that you do not consider affects you, as

another Brigade is mentioned. If you belong to "X" Brigade and

you read that "Y" Brigade does something to-night, you may say

'it is not intended for me;" You lay it aside and go on with

whatever you are doing. Very probably it was anticipated that

you were expected to take co-operating action. To show you how

important it is to take every order on its merits, supposing

a certain Battalion is in a certain part of the line. You have

working parties out repairing, digging, building emplacements,

and you get an order which tells you that the next Battalion

is going to carry out an enterprise to-night. You may say "This

doesn't affect me; I am going to carry on;" But it does affect

you. While their enterprise is going on, the enemy artillery

is going to retaliate wildly all over the place. Your working

parties will suffer very heavily. The issuer of the order sent

you that that you might safeguard your men when your neighbouring

unit or other unit is carrying out an operation. Nobody ever told

you that anybody knew you had working parties out, but the order

was sent to you in case it might affect you, so that you should

know what was going on, and, in the way that I have indicated

very important action was, in such a case, necessary by you. No

man can ever afford to take an order, glance at it superficially,

wash it out and put it aside. No order is ever issued without

a purpose, unless issued by mistake, which very rarely parely happens.

He should then ask himself the question, "Am I intended to take

any action, or not?" Very, very often orders reach you which

superficially do not affect you, But upon serious examination

you will find that these orders do affect you. I remember a very

striking case where action was taken up by a Brigade. I was associated

with a neighbouring Unit which was going to attack. This

Brigade got information of it. They brought up all their working

parties under cover, and brought up stretcher bearers to help

if wanted, and established dressing stations. There were no

orders to do so, but yet they appreciated their duties so well,

they took it upon themselves to take this action and get stretcher

bearers on the flanks, and ready for hard work at a moment's

notice, and they were required, too. That is an example of

acting on orders which are not draftedf for your instruction.

In regard to orders generally, if you are not

perfectly clear about order, do not hesitate to ask questions.

Notwithstanding that despatch riders are overworked and lines

chock-a-block with communications, you are quite right to inquire

if there is any doubt or ambiguity, and by all means send a

telegram and inquire what about paragraph so and so, and what is

really to be done. And take your Snub: It is better to put up a

question and get your Snub than to make a mistake and mess up

the whole operation. Unless an Officer worries unduly or unnecessarily,

I will take care he is not snubbed for asking questions

in this Division. There is an unfortunate tendency amongst minor

Australians to criticise one another, and their Superiors,

and Senior Officers as well as Junior Officers are the offenders.

It is bad business and quite prejudicial to military discipline.

Loyalty to your superiors is a fine thing, and Commanders should

always try to earn it. But unfortunately they do not always have

it. It is mighty easy being loyal to a man who is your superior

when you agree with him, and he does what you expect him to do,

and you are pleased to be with him. But the loyalty we want is

loyalty to the man when you think he is unnecessarily severe,

critical or wrong, when he is adopting a course of action which

you feel and know to be incorrect. It is when he knows he will

get your obedience in letter and spirit even though you don't

agree with him and his commands, that counts. That

– 5 –.

That is the only kind of loyalty that is worth

a damn, or counts at all. I do not suggest that you will do

behind your Seniors' backs things that you were told not to do.

Or fail to do things you were instructed to do. But there is a

tendency to criticise. Wipe it out Gentlemen; Do not permit it

with subordinates. Not even with your Senior Officers. Do not

allow two Subordinates to dismiss the propriety or wisdom or

efficiency of even orders. It is bad for the Division and

the whole force. It creates a bad spirit which leads to inefficiency

and failure in battle. Let us have these things cut

out in this Division. It is an easy principle, and merely

wants and requires strength of character and control of

speech on the part of Officers and Commanding Officers to

put it down. Adverse criticism of even orders means that

their execution is an action done, as it were, under protest.

It is very much against all prudent principles of war, and wants

to be stamped out.

I should now like to say a little about the

personnel and their welfare. I want to put it on a bed-rock

basis, and say to you that I am not doing it solely or even

at all on the grounds of humanity, but on the grounds of

expediency. That, after all is said and done, the man in

the ranks in your working tool, your master-tradesman, your

working implement, and it is up to you to see that he is

always kept sharp and fit so that you will be able to use

him when called upon. Do not be as foolish as the Carpenter

who refused to sharpen his tools. The fitness of the fighting

soldier depends upon food, and rest, and upon his being

made as comfortable as possible under the circumstances, on

all occasions. We do not look after him the way we do or try

to do, because we think it is human and he is our fellow-man,

and we ought to do it, but because we want to keep him going

as a fighting machine. Because if he falls below par, he will

not have the physical endurance to do his tasks. We keep

him protected, and as secure as we can to preserve his fighting

efficiency. We must look at the problem as it stands. Not

from a humanitarian point of view but from an efficiency

point of view. For that reason your constant care should be

to see that the man gets plenty of rest. A man can fight

reasonably well when hungry, but he cannot fight at all

when he is dog-tired for want of sleep. I am sure that men

are in fact played out quicker on account of loss of sleep

than want of food. Our means of bringing up supplies are so

good that it very rarely happens that a man gets separated

from the opportunity of getting food. That depends upon

the efficiency of the section of certain subordinates, such

as the Quartermasters, Quartermaster-Sergeants, etc. The

question of sleep is very much upon the Company Commander, and

almost entirely on his hands. It is owing to his skill and

ability to supervise subordinates, though it also depends

upon the Company's dispositions and arrangements.

I remember when we first went into the line

at Bois xxxxxx Grenier. I visited the Battalion on the right, and

asked how things were. I got the cheerful reply 'not many

casualties, not very tired;" and the remark passed me by.

But upon inspecting the men I found them absolutely played

out. They hadn't slept for four days and four nights, except

for dozes during the day time. This Battalion had got

itself worked up into a condition of the highest possible

nervousness and were unable, owing to their condition, to

take part in operations either defensive or offensive.

They thought that everybody should stop awake all night

and peer over the parapets, and that every minute there was

going to be an attack launched. The Battalion Commander

was told (and sharply, too) and soon mended his ways. That

Battalion had got into difficulties because of no proper

organisation of duties and tasks. The Commander was so

anxious about raids, counter-raids, and shelling, that he

thought the only thing to do would be forx the men to sit

up all night and keep a look-out. I hope you know better

than that. But it is very liable to happen. The tendency

is towards its happen unless checked. If left to himself the

– 6 –

average men will try to get a sleep under a breastwork or somewhere.

But under the circumstances I mention he was not left

sufficiently alone. A Commander's first concern ought to be "What

is the maximum number of men I can get rest for? What is the minimum

number of men I can keep ax lookout with and meet an emergency.

That is to get the maximum of sleep for all Officers, Non-Commissioned

Officers and men and the Battalion Commander himself. If the

command is properly organized and the defence is properly organized,

it should be perfectly possible to adjust the command I have in view,

by stressing the least number of the personnel as possible. That

means in practice that every man will get at night time (the normal

time to sleep) two nights rest out of three, apart from what he

can snatch during the day. It is practical but not a bit academic

Keep in view the means of safeguarding your men's rest.

In connection with rosters of duty, I have discovered

that a good many people, particularly Non-Commissioned

Officers, think that a duty roster means nothing more than the

allocation of certain individuals to certain duties and then

you are done with it. This is not what it means at all. It means,

in a Military sense, the proper rotation of duties so that everybody

in turn gets the tough job, and everybody in turn gets the

easy job., so that any one fraction of a Unit, or this Unit as a

whole, is not unduly stressed. That is why you always keep a

reserve, never putting all in the line at once. That is why

platoons, companies, battalions, brigades, and divisions etc.,

change periodically and get their turn of hard work, and slack

work. That is done by properly drawn up rosters of duties. The

rotation of duties throughout is the secret of success in distributing

stress of duties over the maximum reserve of fighting

efficiency.

As regards the question of keeping men fit, mentally

and morally, Times are when things look pretty thin. At

Gallipoli you will know, some of you, that people started to grouse

and I regret to say, started to grouse in the hearing of their

men. Some were very promptly dealt with when discovered. It is

the first duty of every Officer, no matter how he may feel, to keep

himself and men cheerful, and, no matter how bad the situation,

to blot it out. We are going to face winter conditions, but we

must pretend to like them. It is going to be wet and muddy, and

uncomfortable, and there will be losses. But we are going to kid

ourselves we are going to have the greatest time of our lives,

and so infuse cheerfulness into the men, and this can be done

now, and during the period of passive resistance through which

we will pass before seriously entering into trench life and

offensive warfare. You must never let the men hear your Officers

complaining. Never should an Officer say in the hearing of his

men "It is time these men were drawn out, they are played out

and done for;" Any Officer who is guilty of inducing a man to

"feel sorry for himself" is a traitor to his cause. In all circumstances

ensure that the men feel happy,mentally, if they are not

happy physically. I can remember catching Officers in their dugouts

and overhearing them talking about the length of time they

had been in the trenches, and the sickness, and casualties, and

that it was well time they took the men away and gave them rest.

Unfortunately, it was talk under circumstances where men could

hear them, and, I am sorry to say, lots of men came to us and

said they had had enough of it. And this was brought about by the

Officers themselves. The attitude of Officers is very infectious,

and men respond very quickly. For example, supposing a section of

trenches has been heavily shelled. The Officer says "Let us put

it right at once lads; Now to get to work and we'll soon have it

as it was before;" The result will be that the men will set to

work smartly and confidently, and forget probably what they have

been though. By giving his orders in a cheerful way, and encouraging

the men by act and deed, very soon the Officer will

have the whole position restored. The man is accustomed to

obey, and take his order from the Officer, and the Officer's

influence is very potent. If he is gloomy, they will be gloomy

themselves. Send cheerful Officers amongst them, and keep cheerful

Officers amongst them. When things are bad, nothing helps

the men more than to see their Officers moving amonst them.

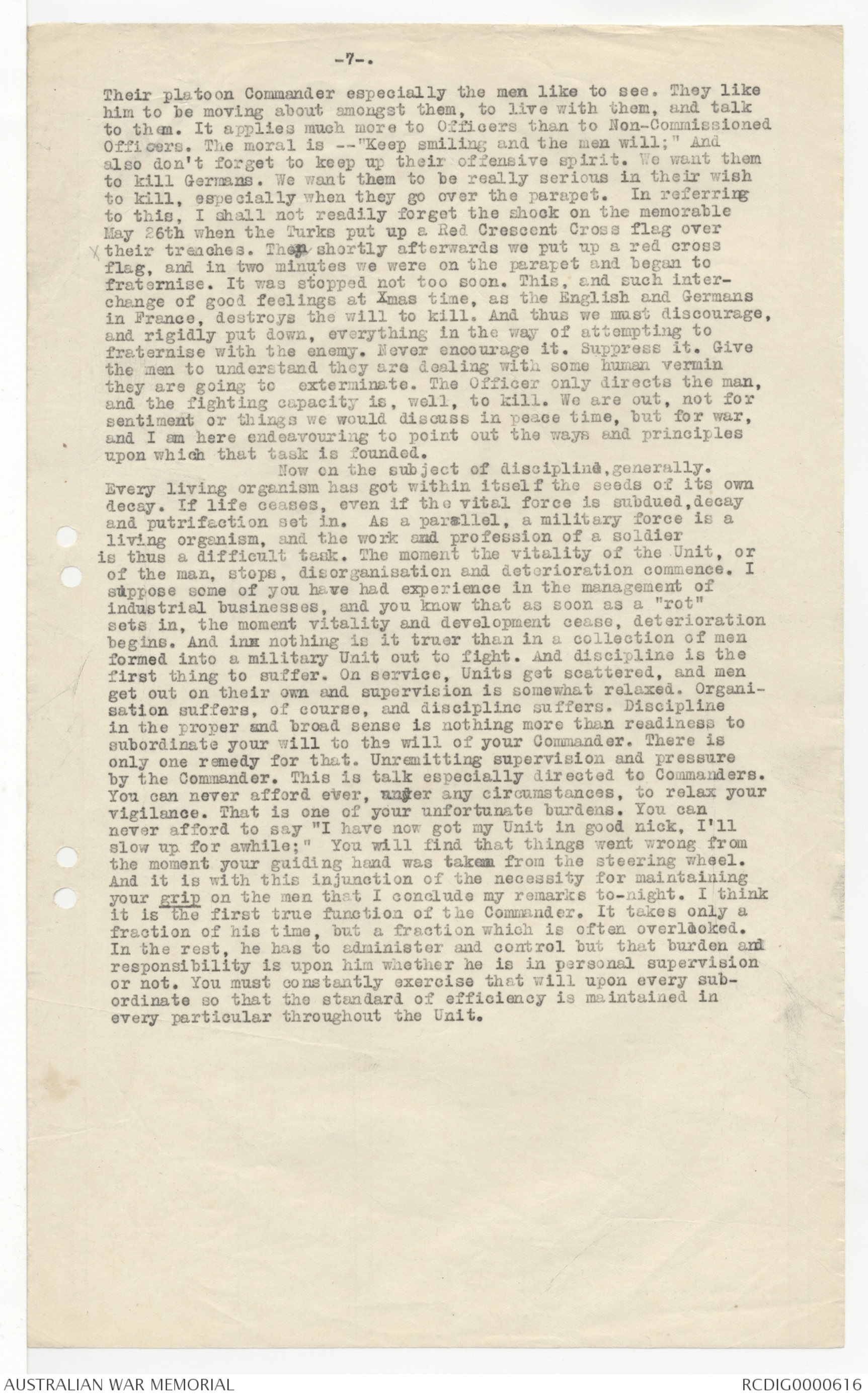

– 7 –

Their platoon Commander especially the men like to see. They like

him to be moving about amongst them, to live with them, and talk

to them. It applies much more to Officers than to Non-Commissioned

Officers. The moral is – – "Keep smiling and the men will;" And

also don't forget to keep up their offensive spirit. We want them

to kill Germans. We want them to be really serious in their wish

to kill, especially when they go over the parapet. In referring

to this, I shall not readily forget the shock on the memorable

May 26th when the Turks put up a Red Crescent Cross flag over

their trenches. Then shortly afterwards we put up a red cross

flag, and in two minutes we were on the parapet and began to

fraternise. It was stopped not too soon. This, and such interchange

of good feelings at Xmas time, as the English and Germans

in France, destroys the will to kill. And thus we must discourage,

and rigidly put down, everything in the way of attempting to

fraternise with the enemy. Never encourage it. Suppress it. Give

the men to understand they are dealing with some human vermin

they are going to exterminate. The Officer only directs the man,

and the fighting capacity is, well, to kill. We are out, not for

sentiment or things we would discuss in peace time, but for war,

and I am here endeavouring to point out the ways and principles

upon which that task is founded.

Now on the subject of discipline, generally.

Every living organism has got within itself the seeds of its own

decay. If life ceases, even if the vital force is subdued,decay

and putrification set it. As a parallel, a military force is a

living organism, and the work and profession of a soldier

is thus a difficult task. The moment the vitality of the Unit, or

of the man, stops, disorganisation and deterioration commence. I

suppose some of you had experience in the management of

industrial businesses, and you know that as soon as a "rot"

sets in, the moment vitality and development cease, deterioration

begins. And inx nothing is it truer than in a collection of men

formed into a military Unit out to fight. And discipline is the

first thing to suffer. On service, Units get scattered, and men

get out on their own and supervision is somewhat relaxed. Organisation

suffers, of course, and discipline suffers. Discipline

in the proper and broad sense is nothing more than readiness to

subordinate your will to the will of your Commander. There is

only one remedy for that. Unremitting supervision and pressure

by the Commander. This is talk especially directed to Commanders.

You can never afford ever, under any circumstances, to relax your

vigilance. That is one of your unfortunate burdens. You can

never afford to say "I have now got my Unit in good nick, I'll

slow up for awhile;" You will find that things went wrong from

the moment your guiding hand was taken from the steering wheel.

And it is with this injunction of the necessity for maintaining

your grip on the men that I conclude my remarks to-night. I think

it is the first true function of the Commander. It takes only a

fraction of his time, but a fraction which is often overlooked.

In the rest, he has to administer and control but that burden and

responsibility is upon him whether he is in personal supervision

or not. You must constantly exercise that will upon every subordinate

so that the standard of efficiency is maintained in

every particular thoughout the Unit.

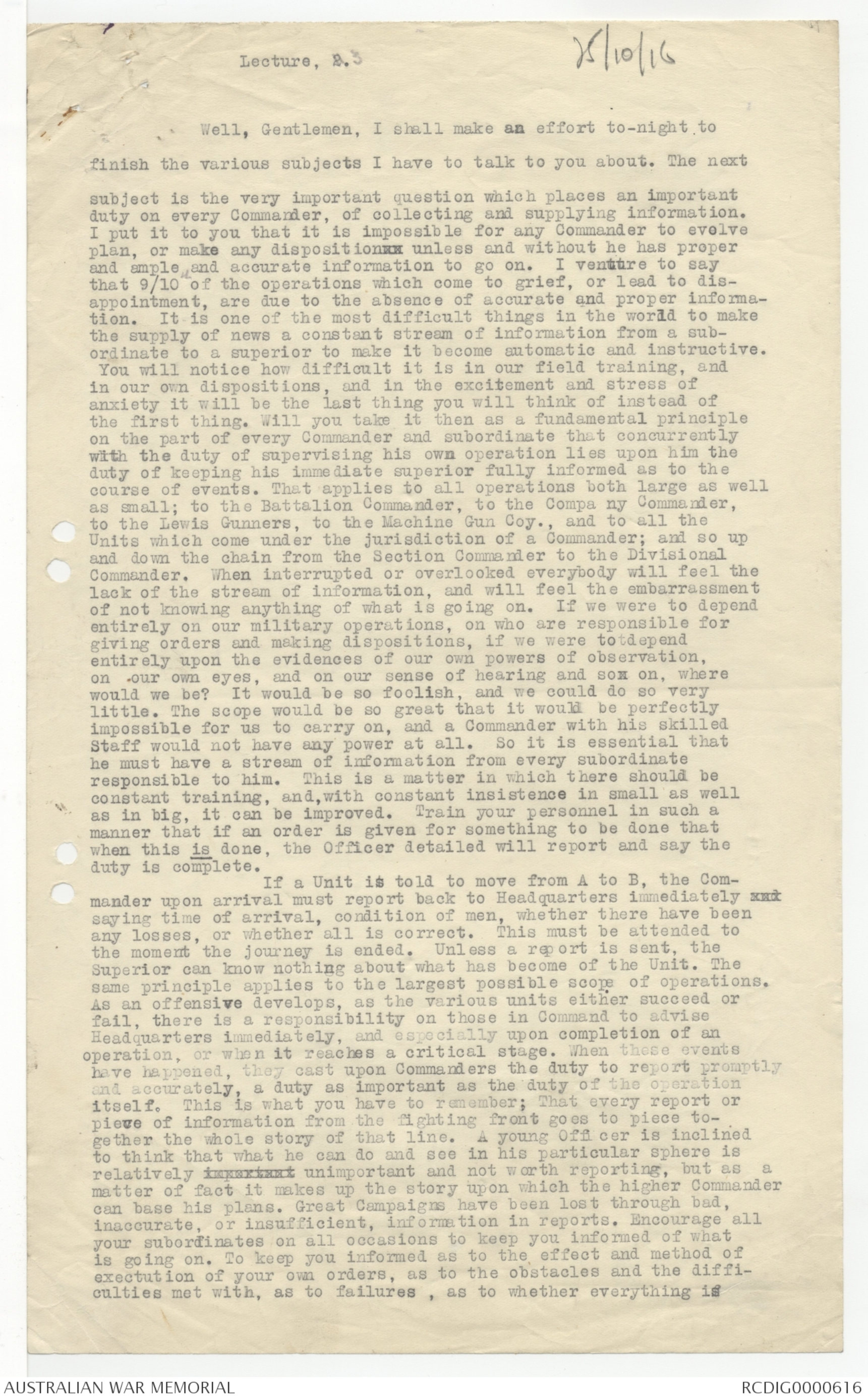

Lecture, 2. 3

25/10/16

Well, Gentlemen, I shall make effort to-night to

finish the various subjects I have to talk to you about. The next

subject is the very important question which places an important

duty on every Commander, of collecting and supplying information.

I put it to you that is is impossible for any Commander to evolve

plan, or make any dispositionxx unless and without he has proper

and ample and accurate information to go on. I venture to say

that 9/10th of the operations which come to grief, or lead to disappointment,

are due to the absence of accurate and proper information.

It is one of the most difficult things in the world to make

the supply of news a constant stream of information from a subordinate

to a superior to make it become automatic and instructive.

You will notice how difficult it is in our field training, and

in our own dispositions, and in the excitement and stress of

anxiety it will be the last thing you will think of instead of

the first thing. Will you take it then as a fundamental principle

on the part of every Commander and subordinate that concurrently

with the duty of supervising his own operation lies upon him the

duty of keeping his immediate superior fully informed as to the

course of events. That applies to all operations both large as well

as small; to the Battalion Commander, to the Compa ny Commander,

to the Lewis Gunners, to the Machine Gun Coy., and to all the

Units which come under the jurisdiction of a Commander; and so up

and down the chain from the Section Commander to the Divisional

Commander. When interrupted or overlooked everybody will feel the

lack of the stream of information, and will feel the embarrassment

of not knowing anything of what is going on. If we were to depend

entirely on our military operations, on who are responsible for

giving orders and making dispositions, if we were to depend

entirely upon the evidences of our own powers of observation,

on our own eyes, and on our sense of hearing and sox on, where

would we be? It would be so foolish, and we could do so very

little. The scope would be so great that it would be perfectly

impossible for us to carry on, and a Commander with his skilled

Staff would not have any power at all. So it is essential that

he must have a stream of information from every subordinate

responsible to him. This is a matter in which there should be

constant training, and, with constant insistence in small as well

as in big, it can be improved. Train your personnel in such a

manner that if an order is given for something to be done that

when this is done, the Officer detailed will report and say the

duty is complete.

If a Unit is told to move from A to B, the Commander

upon arrival must report back to Headquarters immediately and

saying time of arrival, condition of men, whether there have been

any losses, or whether all is correct. This must be attended to

the moment the journey is ended. Unless a report is sent, the

Superior can know nothing about what has become of the Unit. The

same principle applies to the largest possible scope of operations.

As an offensive develops, as the various units either succeed or

fail, there is a responsibility on those in Command to advise

Headquarters immediately, and especially upon completion of an

operation, or when it reaches a critical stage. When these events

have happened, they cast upon Commanders the duty to report promptly

and accurately, a duty as important as the duty of the operation

itself. This is what you have to remember; That every report or

piece of information from the fighting front goes to piece together

the whole story of that line. A young Officer is inclined

to think that what he can do and see in his particular sphere is

relatively important unimportant and not worth reporting, but as a

matter of fact it makes up the story upon which the higher Commander

can base his plans. Great Campaigns have been lost through bad,

inaccurate, or insufficient, information in reports. Encourage all

your subordinates on all occasions to keep you informed of what

is going on. To keep you informed as to the effect and method of

exectution of your own orders, as to the obstacles and the difficulties

met with, as to failures, as to whether everything is

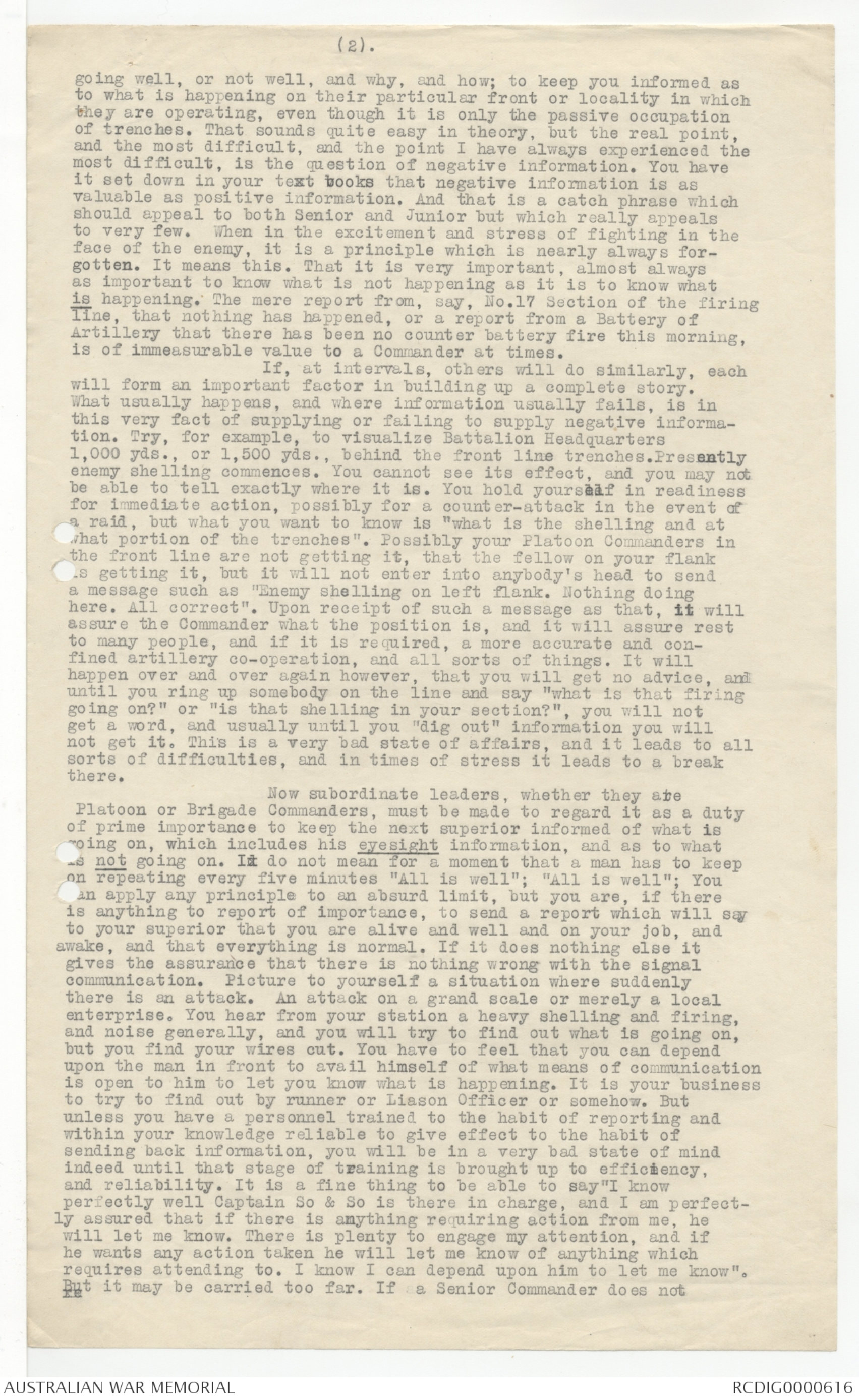

(2).

going well, or not well, and why, and how; to keep you informed as

to what is happening on their particular front or locality in which

they are operating, even though it is only the passive occupation

of trenches. That sounds quite easy in theory, but the real point,

and the most difficult, and the point I have always experienced the

most difficult, is the question of negative information. You have

it set down in your text books that negative information is as

valuable as positive information. And that is a catch phrase which

should appeal to both Senior and Junior but which really appeals

to very few. When in the excitement and stress of fighting in the

face of the enemy, it is a principle which is nearly always forgotten.

It means this. That it is very important, almost always

as important to know what is not happening as it is to know what

is happening. The mere report from, say, No. 17 Section of the firing

line, that nothing has happened, or a report from a Battery of

Artillery that there has been no counter battery fire this morning,

is of immeasurable value to a Commander at times.

If at intervals, others will do similarly, each

will form an important factor in building up a complete story.

What usually happens, and where information usually fails, is in

this very fact of suppplying or failing to supply negative information.

Try, for example, to visualize Battalion Headquarters

1,000 yds., or 1,500 yds., behind the front line trenches. Presently

enemy shelling commences. You cannot see its effect, and you may not

be able to tell exactly where it is. You hold yourself in readiness

for immediate action, possibly for a counter-attack in the event of

a raid, but what you want to know is "what is the shelling and at

what portion of the trenches". Possibly your Platoon Commanders in

the front line are not getting it, that the fellow on your flank

is getting it, but it will not enter into anybody's head to send

a message such as "Enemy shelling on left flank. Nothing doing

here. All correct". Upon receipt of such a message as that, it will

assure the Commander what the position is, and it will assure rest

to many people, and if it is required, a more accurate and confined

artillery co-operation, and all sorts of things. It will

happen over and over again however, that you will get no advice, and

until you ring up somebody on the line and say "what is that firing

going on?" or "is that shelling in your section?" you will not

get a word, and usually until you "dig out" information you will

not get it. This is a very bad state of affairs, and it leads to all

sorts of difficulties, and in times of stress it leads to a break

there.

Now subordinate leaders, whether they are

Platoon or Brigade Commanders, must be made to regard it as a duty

of prime importance to keep the next superior informed of what is

going on, which includes his eyesight information, and as to what

is not going on. Id do not mean for a moment that a man has to keep

on repeating every five minutes "All is well"; "All is well"; You

can apply any principle to an absurd limit, but you are, if there

is anything to report of importance, to send a report which will say

to your superior that you are alive and well and on your job, and

awake, and that everything is normal. If it does nothing else it

gives the assurance that there is nothing wrong with the signal

communication. Picture to yourself a situation where suddenly

there is an attack. An attack on a grand scale or merely a local

enterprise. You hear from your station a heavy shelling and firing

and noise generally, and you will try to find out what is going on,

but you find your wires cut. You have to feel that you can depend

upon the man in front to avail himself of what means of communication

is open to him to let you know what is happening. It is your business

to try to find out by runner or Liaison Officer or somehow. But

unless you have a personnel trained to the habit of reporting and

within your knowledge reliable to give effect to the habit of

sending back information, you will be in a very bad state of mind

indeed until that stage of training is brought up to efficiency,

and reliability. It is a fine thing to be able to say "I know

perfectly well Captain So & So is there in charge, and I am perfectly

assured that if there is anything requiring action from me, he

will let me know. There is plenty to engage my attention, and if

he wants any action taken he will let me know of anything which

requires attending to. I know I can depend upon him to let me know".

But it may be carried too far. If a Senior Commander does not

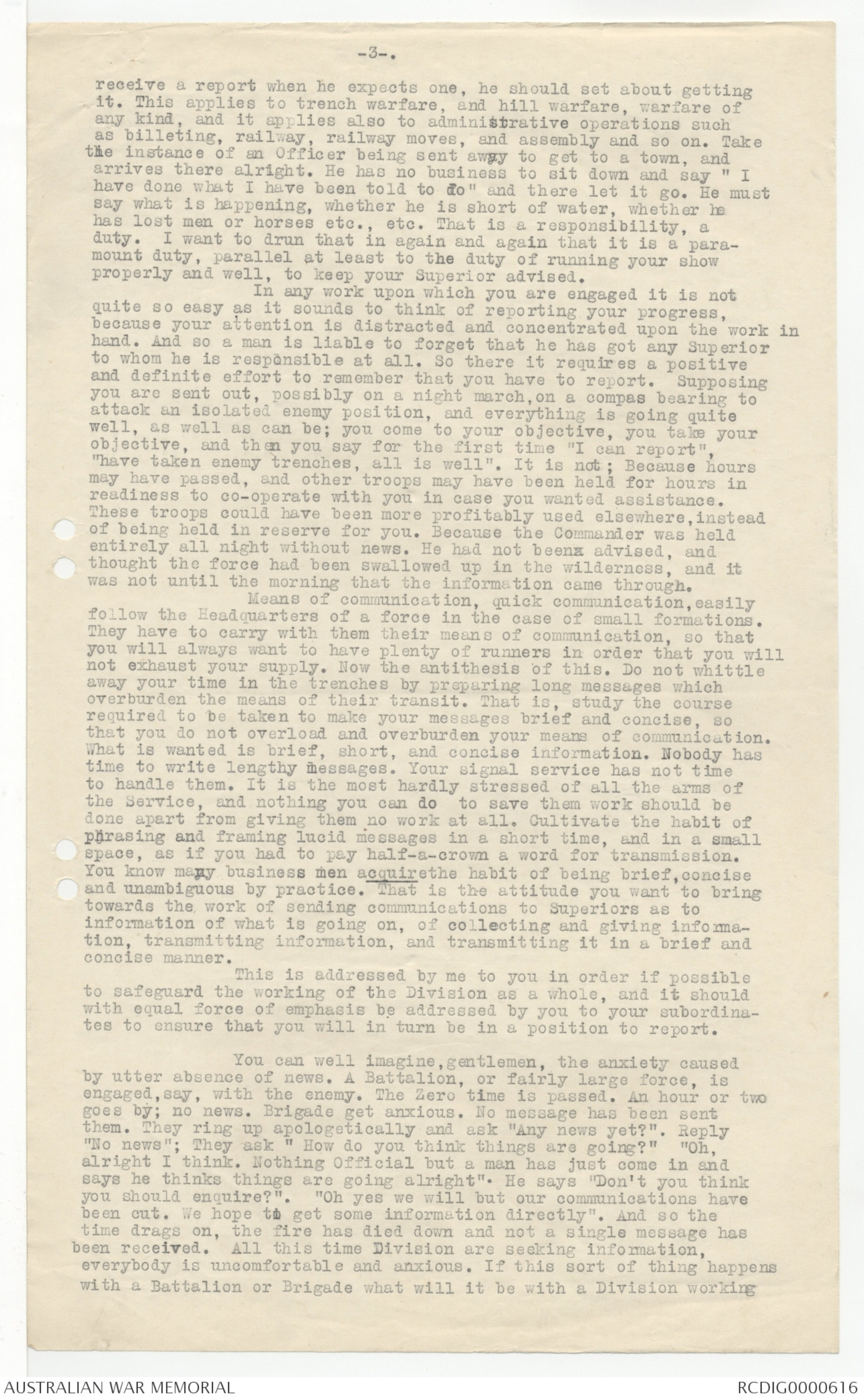

-3-

receive a report when he expects one, he should set about getting

it. This applies to trench warfare, and hill warfare, warfare of

any kind, and it applies also to administrative operations such

as billeting, railway, railway moves, and assembly and so on. Take

the instance of an Officer being sent away to get to a town, and

arrives there alright. He has no business to sit down and say "I

have done what I have been told to do" and there let it go. He must

say what is happening, whether he is short of water, whether he

has lost men or horses etc., etc. That is a responsibility, a

duty. I want to drun that in again and again that it is a paramount

duty, parallel at least to the duty of running your show

properly and well, to keep your Superior advised.

In any work upon which you are engaged it is not

quite so easy as it sounds to think of reporting your progress,

because your attention is distracted and concentrated upon the work in

hand. And so a man is liable to forget that he has got any Superior

to whom he is responsible at all. So there it requires a positive

and definite effort to remember that you have to report. Supposing

you are sent out, possibly on a night march, on a compas bearing to

attack an isolated enemy position, and everything is going quite

well, as well as can be; you come to your objective, you take your

objective, and then you say for the first time "I can report",

"have taken enemy trenches, all is well". It is not; Because hours

may have passed, and other troops may have been held for hours in

readiness to co-operate with you in case you wanted assistance.

These troops could have been more profitably used elsewhere, instead

of being held in reserve for you. Because the Commander was held

entirely all night without news. He had not beenx advised, and

thought the force had been swallowed up in the wilderness, and it

was not until the morning that the information came through.

Means of communication, quick communication, easily

follow the Headquarters of a force in the case of small formations.

They have to carry with them their means of communication, so that

you will always want to have plenty of runners in order that you will

not exhaust your supply. Now the antithesis of this. Do not whittle

away your time in the trenches by preparing long messages which

overburden the means of their transit. That is, study the course

required to be taken to make your message brief and concise, so

that you do not overload and overburden your means of communication.

What is wanted is brief, short, and concise information. Nobody has

time to write lengthy messages. Your signal service has not time

to handle them. It is the most hardly stressed of all the arms of

the Service, and nothing you can do to save them work should be

done apart from giving them no work at all. Cultivate the habit of

phrasing and framing lucid messages in a short time, and in a small

space, as if you had to pay half-a-crown a word for transmission.

You know many business men acquire the habit of being brief, concise

and unambiguous by practice. That is the attitude you want to bring

towards the work of sending communications to Superiors as to

information of what is going on, of collecting and giving information

transmitting information, and transmitting it in a brief and

concise manner.

This is addressed by me to you in order if possible

to safeguard the working of the Division as a whole, and it should

with equal force of emphasis be addressed by you to your subordinates

to ensure that you will in turn be in a position to report.

You can well imagine, gentlemen, the anxiety caused

by utter absence of news. A Battalion, or fairly large force, is

engaged, say, with the enemy. The Zero time is passed. An hour or two

goes by; no news. Brigade get anxious. No message has been sent

them. They ring up apologetically and ask "Any news yet?. Reply

"No News"; They ask "How do you think things are going?". "Oh,

alright I think. Nothing Official but a man has just come in and

says he thinks things are going alright". He says "Don't you think

you should enquire?' Oh yes we will but our communications have

been cut. We hope to get some information directly". And so the

time drags on, the fire has died down and not a single message has

been received. All this time Division are seeking information,

everybody is uncomfortable and anxious. If this sort of thing happens

with a Battalion or Brigade what will it be with a Division working

-4-.

on a broad front if you cannot get any information from the

different Brigades? What a stress of mind the Commander is in.

The higher command should be quickly and definitely supplied with

accurate information. I could speak for quite another hour on

subordinate phases of this same question, but providing my point

is clear I do not wish to labor the question.

Another topic is the important question of

re-organising your commands after an operation. There again is a

question of training. It is a question which you, with your

unaided efforts cannot solve. It depends on the discipline and

training of subordinate. It must be your business to impress

upon every subordinate that after an offensive has caused dislocation

and disorganization, both in point of personnel and geographical

distribution, it is above everything a Commander's first

business to get in touch with a Superior near him, and say what

he is doing and how many men he has and so on.

One incident on Gallipoli I shall always

remember quite well; it was very illuminating.

On the night of the 6/7th August a column consisting

of over 8,000 troops was marched out at 8 o'clock at night

in a compact body. Then they were thrown on a compas bearing in a

certain direction to clear the country and attack a certain spier.

They were faced with a position on considerable difficulty, also in

most broken country, and in the darkness, so that during the night the

whole of the Brigade was smashed into fragments. There was hardly

anywhere so much as a platoon of men which belonged to another

and were together. They were scattered in small bodies, with half

a platoon here and half a platoon there. Men had lost direction

gone to a flank to clear men off a ridge etc. The operation ended

at 8 o'clock in the morning. Before the operations Officers and

N. C. Os. had been assembled and everybody had it impressed upon

him that when he lost connection he had to detach a man to find it.

Had this been done before the landing at Gallipoli there would not

have been the dispersion of Units and consequent losses. However

this injunction bore fruit on this occasion; as a result in

a very few hours, though the Brigades had been hopelessly mixed up,

in a very few hours the Commanders knew exactly where they were

and were concentrated that night and able to complete the operation

the next evening. At ANZAC it took nearly a week to sort out

Units and get people back to where they belonged. That was a very

remarkable object lesson. If it had not been done, and the Brigades

had to go on, the Commanders would have had to say "I cannot carry

on. I do not know where my command is; I have nobody to command,

therefore I cannot do anything;" If you get disorganized you cease

yo exist. You cease to have a command. There is no use issuing

orders if you do not know where to find your men. Therefore you must

concert matters inx all operations, that where men get detached,

lose direction and get mixed up, they must sit tight, they must

take the initiative and find out where the rest of the Battalion is

and get a message through, saying, "There are 60 of us here. We are

alright and we can hang out until you send for us", and so on.

Your Unit will not be fit for fighting and sustained fighting

unless you xcan make the point of initiative good and ensure that it

is done. If you can infuse that spirit of self-help in all the

Units, you will find that things will work much more smoothly and

that otherwise it will be chaos. I can give instances of where a

Battalion in half an hour became no battalion at all. If applies

where the amount of dispersion is only local, extending over a

particular frontage, or where the dispersion is extremex, as in the

example I have given.

Of course, gentleman, I can speak on a great

number of these subjects which really interest and concern you, but

I only pick out those which the members of my staff have probably

not dealt with, nor not dealt with at any length, in their addresses

to you. Referring to purely tactical matters, the subject has not

been exhaustive, and I have endeavoured to limit it to those matters

which are transcendently important. The remainder are more, if I

might say so, administration and psychological, and to-night I want

to say a very serious word to you upon the question of your losses.

Now war is a very cruel thing, and I strongly recommend that you all

try to visualize the possibilities that are before you are so strongly.

-5-

that they won't take you by surprise. Many a good man has ruined

his xxxxxxx Military reputation in this war through having

failed to visualize possiblities, and has been overwhelmed at the

last moment with things he might very well have anticipated if he

had thought about them.

Over and over again I have seen men paralysed

because they have lost men whom they have relied upon. They

are overwhelmed with the loss and death and blood-shed. You must

get yourself into a callous state of mind. A commander who worries,

is not worth a damn, is not a bit good. You are going to have

losses, you do not know whom it is going to affect. Make up your

minds you are not going to worry. It will do after the war. Other

people, well outside the sphere of operations, will worry. You are

concerned enough with the operation in hand. If you are knocked off

your perch because somebody has been killed or taken prisoner, if

he is going to sit down and wring his hands, the sooner he is sent

back to the base, the better. Hypnotise yourself into a state of

complete indifference as to losses. Whether your Battalion is 100

strong or 300 strong, you have got to carry on. Big junks of your

Battalion disappear, but you have got to carry on. It will not be

tolerated because a man says "I have a certain percentage of losses

and cannot carry on." You will think it is almost impertinence on my

part to say this, but I have seen it in Senior and Junior Officers.

Big losses occur and a state of paralysis takes command of the

Officer. It happened in Gallipoli and in France. It will happen

again, and you must give your imagination play so that apart from

your own selves you will be utterly callous of your losses. It is

certainly hard to see an Officer's men thinned out, with your

best friends all missing after the battle, but that is what war is to

you if you regard it at the normal, not the abnormal, thing. The man

who can think of the thing objectively, not subjectively, is the

man who is going to succeed. If you allow yourself to be disturbed

by the occurrence of an event which you might readily foretell, then

you are going to suffer through want of foresight.

I am not going to dwell too long on the

matter, but just sufficiently long to warn you to prepare for when

the time comes so that you are not going to be taken unawares,

and that you will carry on coolly and methodically with reduced

numbers. Even if your best friends have gone, as a further assurance

of an equanimity of mind every man ought to know where to lay his hand

on a substitute for every single implement in his kit as tools

and everything will be liable to be lost or destroyed. He must

know where he can lay his hands on a reasonably good substitute to

carry on. The first two Australian Divisions have been carrying on

for 18 months or more, and are just as good to-day as on the first

day they started fighting. A Unit can fight with reduced numbers,

even if 50% of losses have been suffered. Some Commanders still

seem to think that the old method of withdrawing a Unit for reorganization

and rest after having suffered 25% of losses still

holds good. It does not; It is wrong, and has been proved wrong,

even where Senior Officers are sick and wounded and nobody is left

who seems to know anything. Steel your minds to the realization

first of all, that you will have your valuable assistants, coadjutors

etc., drop away from you one by one, and that you can carry

on without them quite well, and perhaps as well. The period of

rest will come. You will be withdrawn, to lick your sores, reorganise

again, and go on as happy as ever. Remember the old Kitchener

doctrine "Carry On" and this, the last thing I have said is the

most important in every particular aspect..

Speaking on casualties and still confining

my remarks to the duties of Commanders, I want to impress upon you

also that a serious responsibility lies upon that casualties

are reported promptly. You have your Adjutants, Orderly Room Clerks

etc, but because of indifference on part of the C.O. that work

is often very, very, badly done, but although the reporting of

casualties correctly does not help to win the war, it does help

to maintain the National morale. The Public quickly notices the

badly conducted casualty reporting. I do not know whether we can

realise in the early months of the Gallipoli Campaign what utter

absence of news there was concerning what was going on, and what

casualties were being suffered. The causalty returns that were

supplied were often wrong, names mis-spelled, and numbers wrong,

Deb Parkinson

Deb ParkinsonThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.