Sir John Monash, Personal Files Book 12, 3 April - 30 April 1916, Part 8

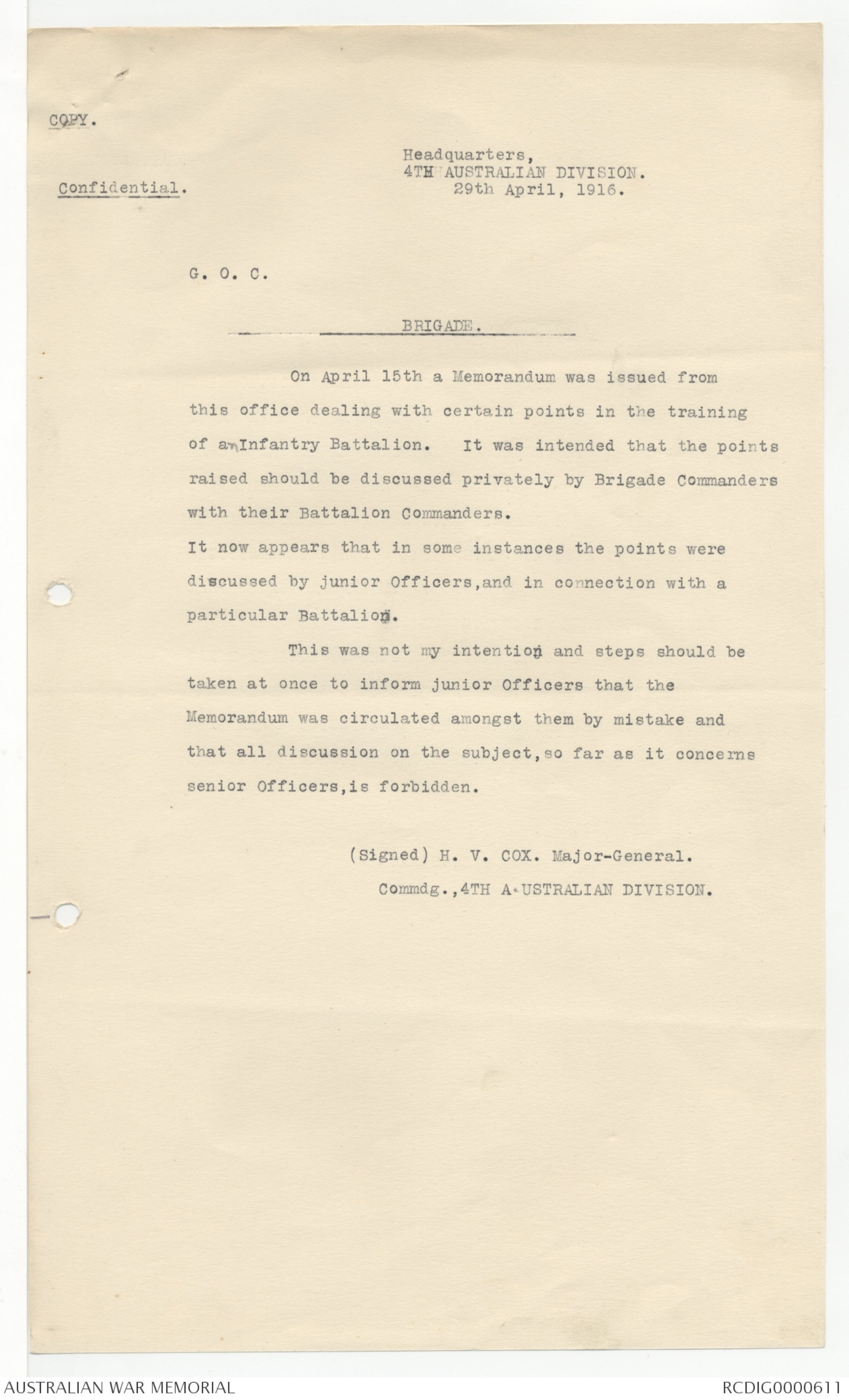

COPY.

Headquarters,

4TH AUSTRALIAN DIVISION.

29th April, 1916.

Confidential.

G. O. C.

BRIGADE.

On April 15th a Memorandum was issued from

this office dealing with certain points in the training

of anInfantry Battalion. It was intended that the points

raised should be discussed privately by Brigade Commanders

with their Battalion Commanders.

It now appears that in some instances the points were

discussed by junior Officers,and in connection with a

particular Battalion.

This was not my intention and steps should be

taken at once to inform junior Officers that the

Memorandum was circulated amongst them by mistake and

that all discussion on the subject, so far as it concerns

senior Officers,is forbidden.

(Signed) H. V. COX. Major-General.

Commdg. ,4TH A-USTRALIAN DIVISION.

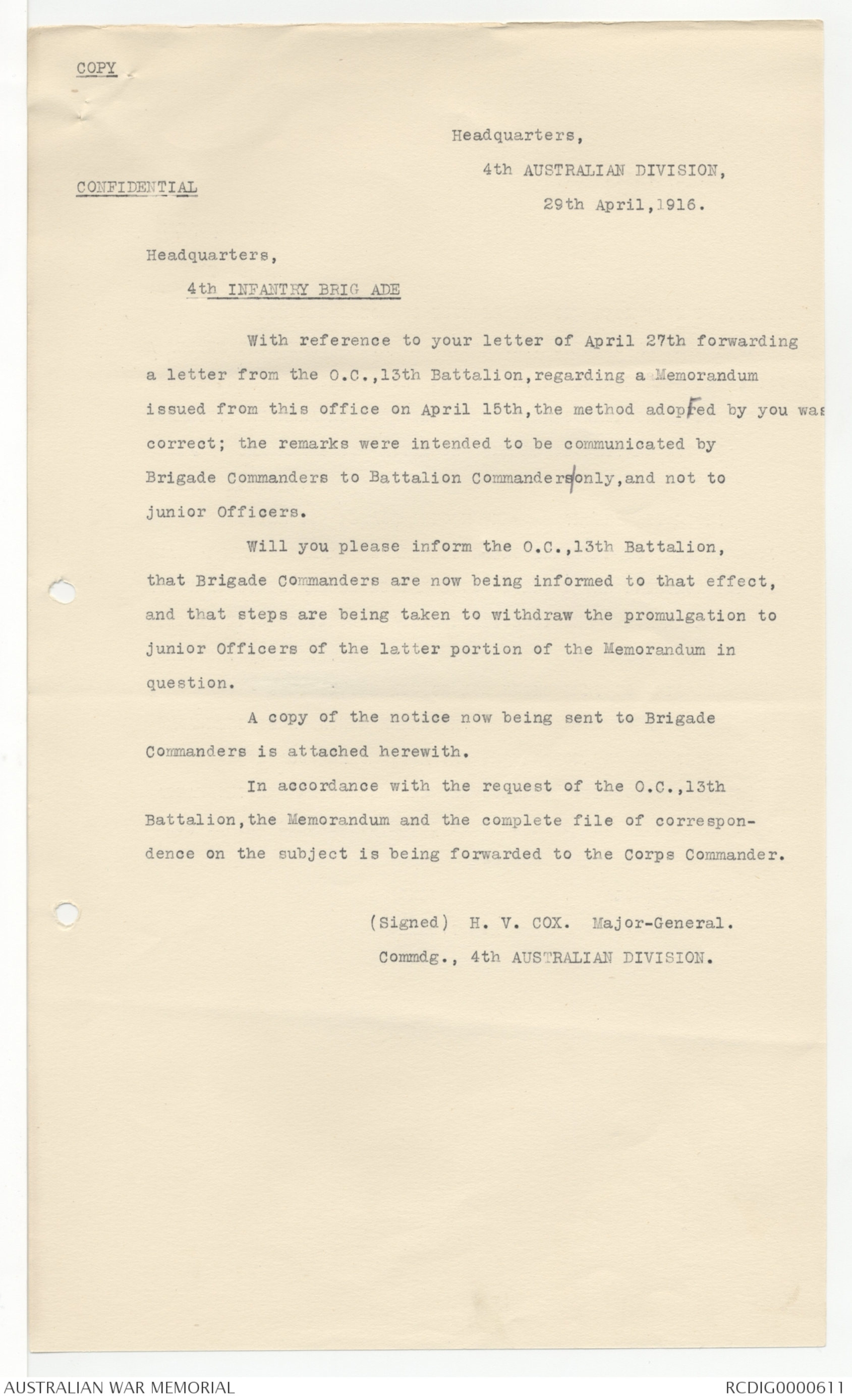

COPY

Headquarters,

4th AUSTRALIAN DIVISION,

29th April,1916.

CONFIDENTIAL

Headquarters,

4th INFANTRY BRIG ADE

With reference to your letter of April 27th forwarding

a letter from the O.C., 13th Battalion, regarding a Memorandum

issued from this office on April 15th, the method adoprted by you was

correct; the remarks were intended to be communicated by

Brigade Commanders to Battalion Commanders/only,and not to

junior Officers.

Will you please inform the O.C.,13th Battalion,

that Brigade Commanders are now being informed to that effect,

and that steps are being taken to withdraw the promulgation to

junior Officers of the latter portion of the Memorandum in

question.

A copy of the notice now being sent to Brigade

Commanders is attached herewith.

In accordance with the request of the O.C.,13th

Battalion,the Memorandum and the complete file of correspondence

on the subject is being forwarded to the Corps Commander.

(Signed) H. V. COX. Major-General.

Commdg., 4th AUSTRALIAN DIVISION.

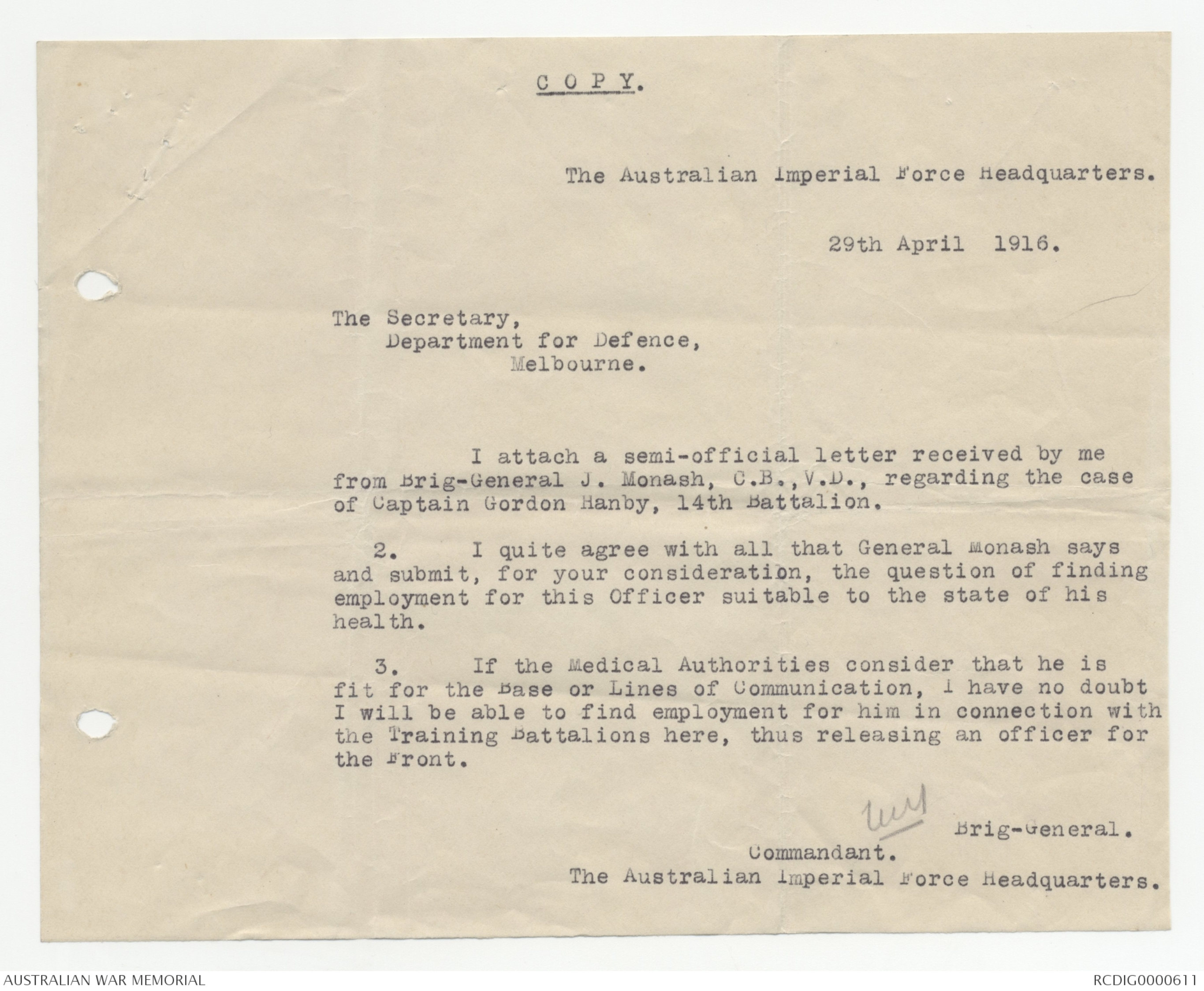

COPY.

The Australian Imperial Force Headquarters.

29th April 1916.

The Secretary,

Department for Defence,

Melbourne.

I attach a semi-official letter received by me

from Brig-General J. Monash, C.B., V.D., regarding the case

of Captain Gordon Hanby, 14th Battalion.

2. I quite agree with all that General Monash says

and submit, for your consideration, the question of finding

employment for this Officer suitable to the state of his

health.

3. If the Medical Authorities consider that he is

fit for the Base or Lines of Communication, I have no doubt

I will be able to find employment for him in connection with

the Training Battalions here, thus releasing an officer for

the Front.

[[?]] Brig-General.

Commandant.

The Australian Imperial Force Headquarters.

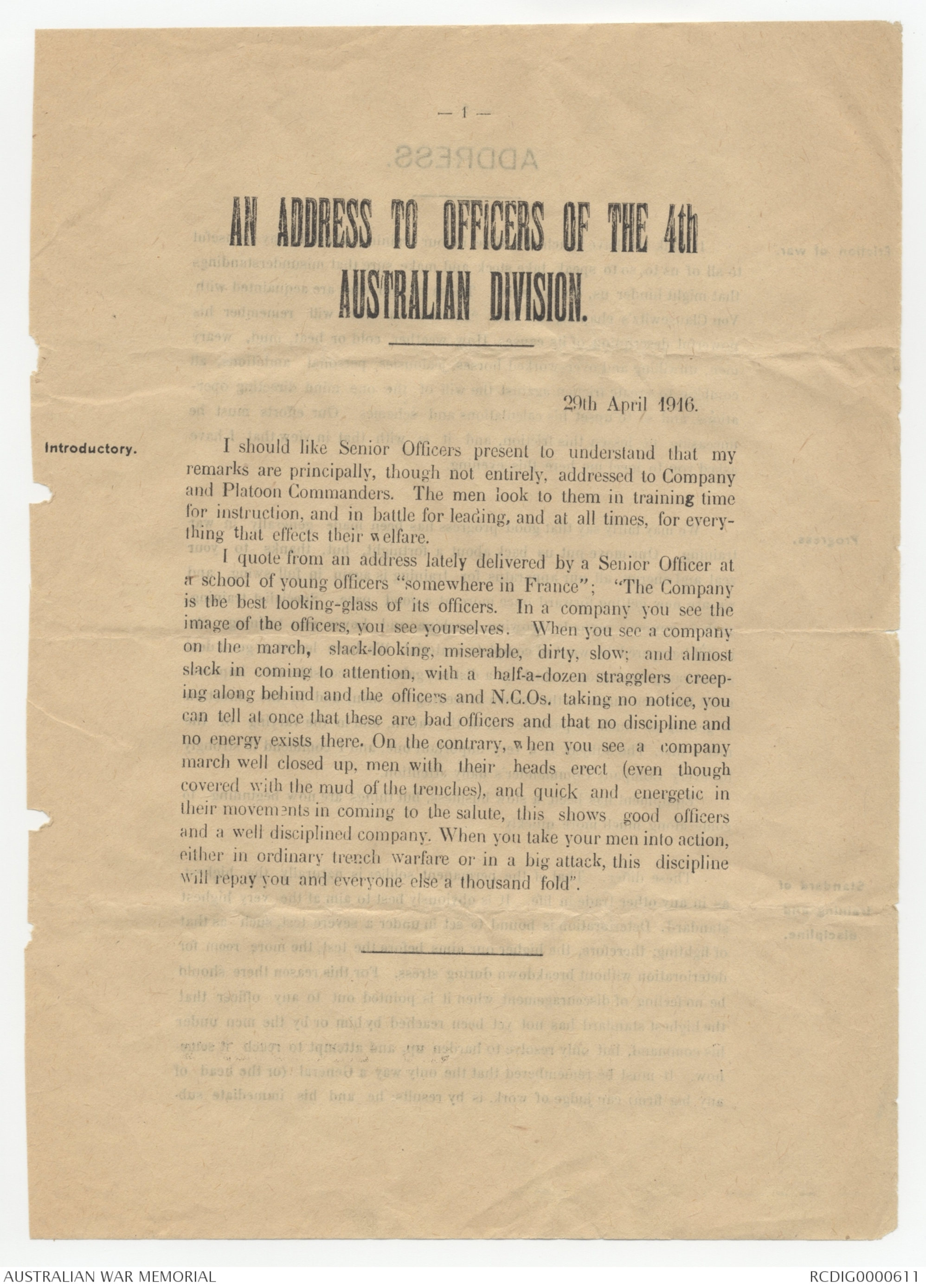

-1-

AN ADDRESS TO OFFICERS OF THE 4th

AUSTRALIAN DIVISION.

29th April 1916.

Introductory. I should like Senior Officers present to understand that my

remarks are principally, though not entirely, addressed to Company

and Platoon Commanders. The men look to them in training time

for instruction, and in battle for leading, and at all times, for everything

that effects their welfare.

I quote from an address lately delivered by a Senior Officer at

a school of young officers "somewhere in France"; "The Company

is the best looking-glass of its officers. In a company you see the

image of the officers, you see yourselves. When you see a company

on the march, slack-looking, miserable, dirty, slow; and almost

slack in coming to attention, with half-a-dozen stragglers creeping

along behind and the officers and N.C.Os taking no notice, you

can tell at once that these are bad officers and that no discipline and

no energy exists there. On the contrary, when you see a company

march well closed up, men with their heads erect (even though

covered with the mud of the trenches), and quick and energetic in

their movements in coming to the salute, this shows good officers

and a well disciplined company. When you take your men into action,

either in ordinary trench warfare or in a big attack, this discipline

will repay you and everyone else a thousand fold".

______________________________

-2-

ADDRESS.

Friction of war. I think we have reached a time in our training where it may be useful

to all of us to, so to speak, take stock and make sure that misunderstandings

that might hinder us, do not exist. Those of you who are acquainted with

Von Clausewitz's chapter, on the "Friction of War" will remember his

powerful description of its causes. How weather, cold or heat, mud, weary

men, unwilling and over-worked horses, jealousies, personal ambitions, all

combine to create friction against the will of the one mind directing operations,

and so to upset his calculations and schemes. Our efforts must be

unceasing to lessen this friction, and it is with that in view that I have

asked you to meet me here this evening.

Progress. We may fairly say that good progress has been made generally in war

training. Our move put us back about a fortnight, but, thanks to your

zeal and energy, all our apparatus for training is again in full swing, and

we are now getting forward once more at a good pace. Specialist training,

such as gunnery, grenade throwing, machine and Lewis gun training, etc

is still hampered by want of complete material. We have learnt a good deal

about camp sanitation, which is a distinct gain, and considerable improvement

has been made in the system of feeding the men, and in the direction

of getting as much as possible out of the ration, and in the varying of the

men's diet. The subject is a very important one, and I commend it strongly

to every Company Commander's daily attention.

Equipment has been a slow business, but things are now beginning to

come along much more quickly.

Standard of training and discipline. These differ. That of the permanent soldier is naturally the highest,

as in any other trade in life. It is obviously best to aim at the very highest

standard. Deterioration is bound to set in under a severe test, such as that

of fighting; therefore, the higher our aims before the test, the more room for

deterioration without breaking down during stress. For this reason there should

be no feeling of discouragement when it is pointed out to any officer that

the highest standard has not yet been reached by him or by the men under

his command, but only resolve to harden up, and attempt to reach it somehow.

It must be remembered that the only way a General (or the head of

any big firm) can judge of work, is by results; he and his immediate

-3-

subordinates supply the driving power and insist on a certain standard. But it

must not be considered that this driving power is applied without knowledge

of, and toleration and sympathy for the difficulties of the others. I am

well aware of them, the multiplicity of duties, at one time, administrative

work pushing aside training work, Court Martial Duty, Divisional Field

Officer's duties, Orderly Officer's duty, frequent change of commanders

each with different ideas, the impossibility of getting his N. C. Os & men

together owing to gards and fatigues, the transfer of men to other

units; all these combine to try the temper, endurance and spirit of a keen

company or platoon commander almost beyond bearing. But such officers

must not forget that they have no monopoly of trials in this respect. Their

Commanding Officers and their Brigadiers have at least an equal share, and

if any of them could spend a whole day with a Divisional Commander, they

would discover that he was not exactly lying on a bed of roses !

Methods of instruction. I think I have been long enough with the Australian soldier to know

something, though not as much as you do, of his peculiarities. They are

mostly due to his bringing up and environment. He is a very intelligent and

independent man ; he takes little or nothing for granted, and thinks for

himself far more than does his English comrade. For this reason, unless

the meaning of any instruction is obvious, it is necessary to explain fully to

him why he is being instructed in any particular subject. I find this is not

always done, and where it is omitted, results are always poor. To take a

case in point - the matter of saluting. I have talked to a great many

Australian soldiers, who evidently dislike saluting, and have found invariably

that their ideas are altogether mistaken. Such men consider that the salute

is a tribute to the particular officer they salute, whereas we know it is only

a necessary mark of respect of the commission the officer holds from the

King, and has nothing whatever to do with the officer personally. They fail

entirely to see the link between good saluting and good discipline; and some

of them think that it is just an honour that officers desire for their own glorification.

Here is another extract from the "Senior Officer" "...but

you cannot be too particular in insisting on a smart, alert, cheerful

appearance, and on the prompt and willing accordance of all honours and

salutes; it is only that Company or that Battalion which shows attention to

all these which really does possess discipline ; without discipline no body of

men will stand an hour of real danger. These matters of appearance and

respect to officers are not eye-wash; they are an outward and visible sign of

the inward and spiritual grace as the parson says". The point I want to

-4-

make here is that while your instructions on every subject must be forcible

(and it can only be so if you know your subject thoroughly) it must leave

your men in no doubt whatever as to exactly what is meant and why it is

important. This leads up to another point, viz, the necessity for strict

discipline during training. I will read you an extract from that excellent

publication "Impressions and reflection of a French Company Officer".

He is arguing that while trench warfare gives cohesion to troops, they are in

danger, after a long spell of it, of losing discipline and their offensive spirit,

and says that for these reasons "during any training period rigid discipline

impossible in trenches, must be maintained. Compliments should be

strictly observed and exactitude in uniform closely supervised.

Nothing is more demoralizing to the soldier than to see his comrades

badly turned out and slack in the performance of their duties. It may sometimes

seem more comfortable to the soldier but in reality he knows that in

such a lawless, ill-disciplined crowd, everybody will desert him in the hour

of danger. The daily sight of a company smartly turned out and well disciplined

gives him, on the other hand, a feeling of comfort and confidence".

But, gentlemen. it must not be forgotten than no Company Officer can insist

on this rigid discipline, often so uncomfortable to the soldier, unless he

places himself under the same discipline. It should be his pride and glory

to undergo the same hardships as his men, and to abide by exactly the

same rules and orders in small as in great matters. I have noticed that

this is not thoroughly appreciated by all of you, and I want to put great

emphasis upon it ; nothing carries greater wight with the men, nothing

influences them more quickly than to realise that their Company and

Platoon Commanders are cheerful partners of their discomforts and privations.

Never think for a moment that because you are an officer a disagreeable

order does not apply to you. As an instance of things in this

respect as they should be, I should like to quote you our battalions of

Guards as one sees them on service. The popular idea of the Guard's officer

is that he cannot exist away from London society, and is unable to do

without all sorts of comforts and luxuries ; never was there a more mistaken

idea. In this respect, as in most others. the Guards are a pattern to the

rest of the British Army. Their officers take everything that comes exactly

as their men, and set a brilliant example of devotion to duty and of self-

sacrifice, while at the same time insisting upon the highest standard of

discipline. I am told that 24 hours after the Guards leave their trenches,

weary and coated with mud from head to foot, they turn out for steady drill

and ceremonial as if they were outside Buckingham Palace.

-5-

Responsibility for seeing that orders are carried out as well as for giving they order that the shall be. This is very important. "I gave the order that it was to be done" is

often taken to be a clearance certificate for the whole affair. It is nothing of

the kind, and should never be accepted as such. I also want[to draw your

attention to the general responsibility of officers for seeing that all orders are

carried out. Corps, Divisional and Brigade as well as regimental or company.

Because an order is a Divisional or Brigade order, it does not rest with only

the Divisional or Brigade Staff to see that it is observed. Every officer must

make it his business. An instance that occurs to me is the order issued

some time ago as to only driving wagons at a walk. Is there a single officer

present who has ever checked or reported drivers for disobeying this order?

No. I thought not and will tell you why. If officers generally had done

their duty in this respect it would have stopped long ago.

The necessity for reading and thinking. If it is to be really effective, the next day's instructional work must be

the subject of reading and thought by every officer after the current day's

work is over, in order that he may start with the new subject fresh in his

mind and be certain of the points he wishes to make. Company Commanders

will do well to discuss the new day's work with their Platoon Commanders

Ten minutes or a quarter of an hour is quite sufficient. It is only in this way

that waste of time next day can be avoided, and the men instead of being

kept waiting, be put through a brisk spell of work in which the most important

points are forcibly rubbed in. Let no officer think for a moment that

because he is well educated, intelligent, and a successful man of business

there is nothing much to learn in soldiering. That attitude is a delusion and

a snare. I grant that common sense is as useful in a military officer as

it is in a business man, but, as in any business, there is lots more required.

I can only tell you, gentlemen, that I have been soldiering hard for nearly

37 years. I am disheartened by my own ignorance at least once a day, and

I have never been content with my knowledge.

The "Senior Officer" says "knowledge is not a heaven sent gift ; it is

the outcome of steady hard work and thought, and it is an absolute necessity

to you as an officer. It is the foundation of your own character, for without

it you cannot gain self-confidence. You must know your job. If you do

not you can have no confidence in yourself, and the men of the Company

will have no confidence in you either. Knowledge is, therefore, the first great

essential for your capacity to command your men. They must feel, not only

that you know your job, but also that you will set an example of courage,

self-sacrifice, and cheerfulness, and will look after their welfare and comfort.

The character of the officer is the foundation of the discipline of his men"

-6-

Now a word to any of you who may be inclined to feel sometimes at

the bottom of your hearts something of this sort - "It is all very well for

the General to talk in this way, and to preach the necessity for all these

things, but we do not notice that the permanent soldiers, have made such a

great success of matters in this war, and mistakes appear to be abundant".

I believe, gentlemen, it will be realised some day when the proper perspective

is established, and matters have had time to sort themselves out, that

considering the new conditions permanent soldiers had to face, their

mistakes have not been so very frequent, and it has been when the politicians

have interfered with the soldier's legitimate work that severe trouble

has occurred. It took that very able man, Abraham Lincoln nearly three

years to discover that the only way to win for the North in the Amercain

Civil War was to let the soldiers run their own show, and I am afraid we

have no Abraham Lincoln with us now.

I should like to touch on a kindred matter, namely, the feeling of the

permanent soldier for those who have voluntarily joined the army since the

war began, because sometimes I think there is a misunderstanding here. I

often fancy that there is a sort of idea among the younger (and so more

sensitive) officers who have joined since the beginning of the war, that the

permanent officer is inclined to be over-critical, perhaps apt to laugh at

mistakes of a technical kind, and to assume an air of superiority. I can

assure you that this is not the case, and that if this tiresome frame of mind

is met with by any of you it will only be among the very young and very

foolish. Those of us permanent soldiers who have thought about the matter

are full of admiration for the patriotism that has placed you where you now

are, and for the stern resolve to do your duty that distinguishes you. I have

oftened wondered whether our patriotism would, in like case, have stood

the test that yours has come so triumphantly through, and have ended by

hoping with a good deal of humility, that it might.

In conclusion let us constantly bear in mind how short the time is

before we enter the principal theatre of this great war, and that we must

work at high pressure through the whole of the period that is left to us. Let

us keep our eyes fixed on our great motives. The suppression of a tyranical

and brutal militarism, the refutation of the abominable doctrine that Might

is Right, the defence of the rights of weaker nations, and of the solemnity

and binding nature of treaties.

-7-

If these great things are kept before us they must incite us to more

stenuous effort, assist us to comtemplate our daily troubles and worries with

patience and toleration, and to dispose of them in such a way as to increase

as little as may be the inevitable "Friction of War".

H.V. COX,

Major General

_____________

Remarks by Brigadier General J. MONASH, C.B

_____________

The General has asked me to add some remarks, and I feel sure that

he would desire that, in doing so, I should apply myself to one or two

themes other than those touched upon by him in the convincing and stimulating

address to which we have listened. And this I shall endeavour to do

In the first place, why do we, on this, as on previous occasions, direct

our appeal specially to and at the Platoon Commander ? It is not because

the principles of command and leadership which have been enunciated to

you do not apply equally well to all officers, senior and junior. It is because

the Platoon Commander is the man who stands in the most intimate contact

with, and the most direct relationship to, the personnel. It is because it is

through him, and by his agency, and by none other, that we can

reach the man in the ranks, and can achieve the highest fighting efficiency.

It is because the Platoon is, for all purposes, the unit for whose

perfection we strive. Because a perfect Platoon means a perfect Battalion

and Brigade and Division ; and the efficiency of an Army Corps is to be

measured by that of its Platoons. The Platoon is the compact unit of some

fifty men committed to the sole care of a single officer, and that officer

must look to it that, in all things, he fails in no respect in his responsibility

to and for those fifty men.

And in making this appeal to Platoon Commanders, for the exercise of

their highest powers and for the practice of their greatest self-devotion. I do

so with the consciousness that it is very necessary to remind ourselves,

sometimes, how great, how responsible, is the duty which is laid upon us

all. Removed as we are from the centre of things, living as we are, so to

say, on the fringe of the Empire's activities, in an atmosphere of monotonous

war training in this desert, and without the hourly stimulus of great and

Jen

Jen This transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.