Sir John Monash - Personal Files Book 2, 1 April - 11 April 1915, Part 1

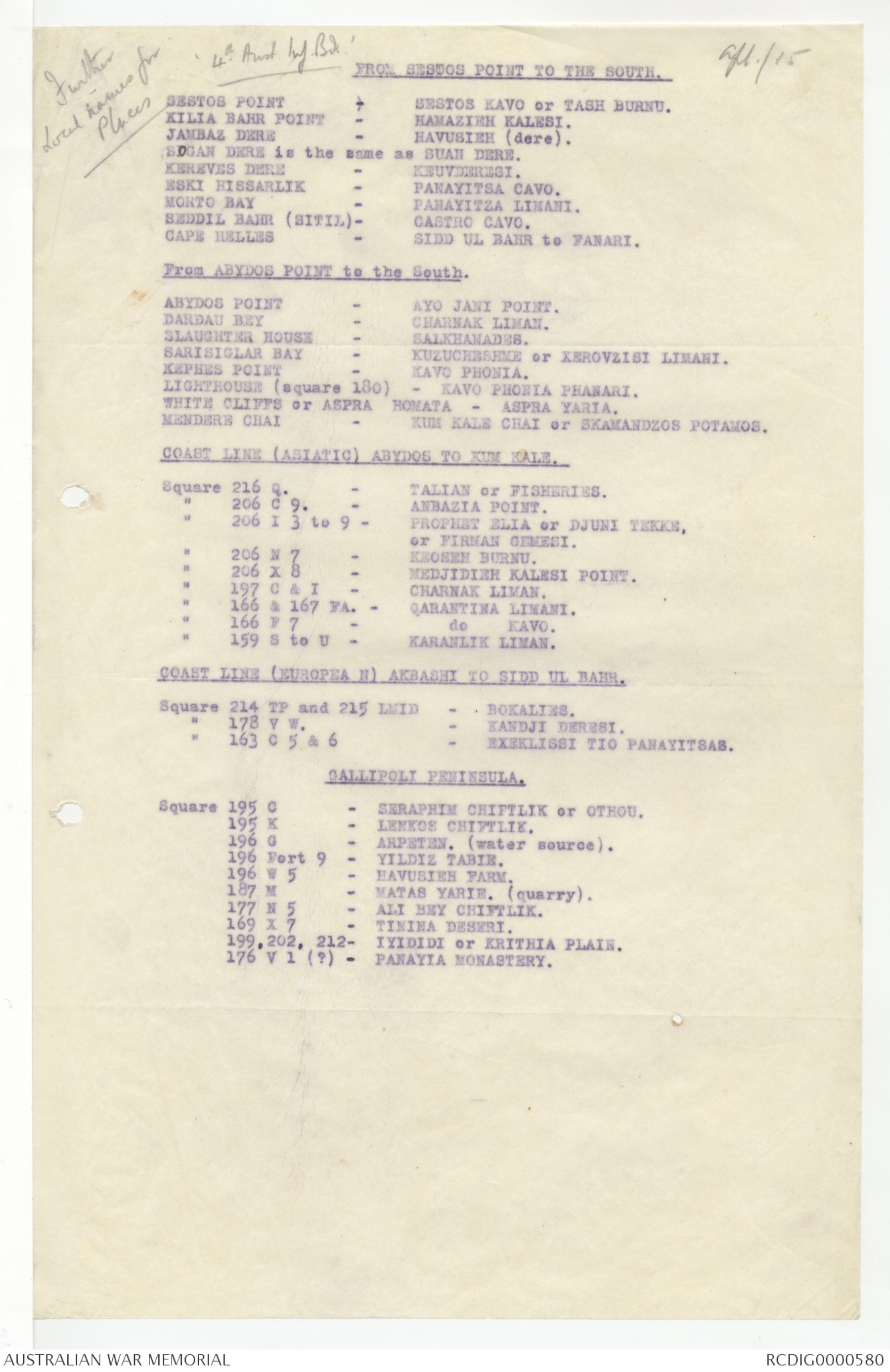

[*Further Local Names for Places*]

'4th Aust. Inf. Bde.'

Apl,/15

FROM SESTOS POINT TO THE SOUTH

SESTOS POINT - SESTOS KAVO or TASH BURNU.

KILIA BAHR POINT - HAMAZIEH KALESI.

JAMBAZ DERE - HAVUSIEH (dere).

SOGAN DERE is the same as SUAN DERE.

KEREVES DERE - KEUVDERESI.

ESKI HISSARLIK - PANAYTSA CAVO.

MORTO BAY - PANAYITZA LIMANI.

SEDDIL BAHR (SITIL) - CASTRO CAVO.

CAPE HELLES - SIDD UL HABH to FANARI.

From ABYDOS POINT to the South.

ABYDOS POINT - AYO JANI POINT.

DARDAU BEY - CHARNAK LIMAN.

SLAUGHTER HOUSE - SALKHANADES.

SARISIGLAR BAY - KUZUCHESHME or XEROVZISI LIMANI.

KEPHES POINT - KAVO PHONIA.

LIGHTHOUSE (square 180) - KVAO PHONIA PHANARI.

WHITE CLIFFS OR ASPRA HOMATA - ASPRA YARIA.

MENDERE CHAI - KUM KALE CHAI or SKAMANDZOS POTAMOS.

COAST LINE (ASIATIC) ABYDOS TO KUM KALE.

Square 216 Q. - TALIAN or FISHERIES.

" 206 C 9. - ANBAZIA POINT.

" 206 I 3 to 9 - PROPHET ELIA or DJUNI TEKKE,

or FIRMAN GEMESI.

" 206 N 7 - KOESEH BURNU.

" 206 X 8 - MEDJIDIEH KALESI POINT.

" 197 C & I - CHARNAK LIMAN.

" 166 & 167 FA. - QARANTINA LIMANI.

" 166 F 7 - do KAVO.

" 159 S TO U - KARANLIK LIMAN.

COAST LINE (EUROPEA N) AKBASHI TO SIDD UL BAHR.

Square 214 TP and 215 LMID - BOKALIES.

" 178 V W. - KANDJI DERESI.

" 163 C 5 & 6 - EXEKLISSI TIO PANAYITSAS.

GALLIPOLI PENINSULA.

Square 195 C - SERAPHIM CHIFTLIK or OTHOU.

195 K - LENKOS CHIFTLIK.

196 G - ARPETEN. (water source).

196 Fort 9 - YILDIZ TABIE.

196 W 5 - HAVUSIEH FARM.

187 M - MATAS YARIE. (quarry).

177 N 5 - ALI BEY CHIFTLIK.

169 X 7 - TININA DESERI.

199, 202, 212 - IYIDIDI or KRITHIA PLAIN.

176 V 1 (?) - PANAYIA MONASTERY.

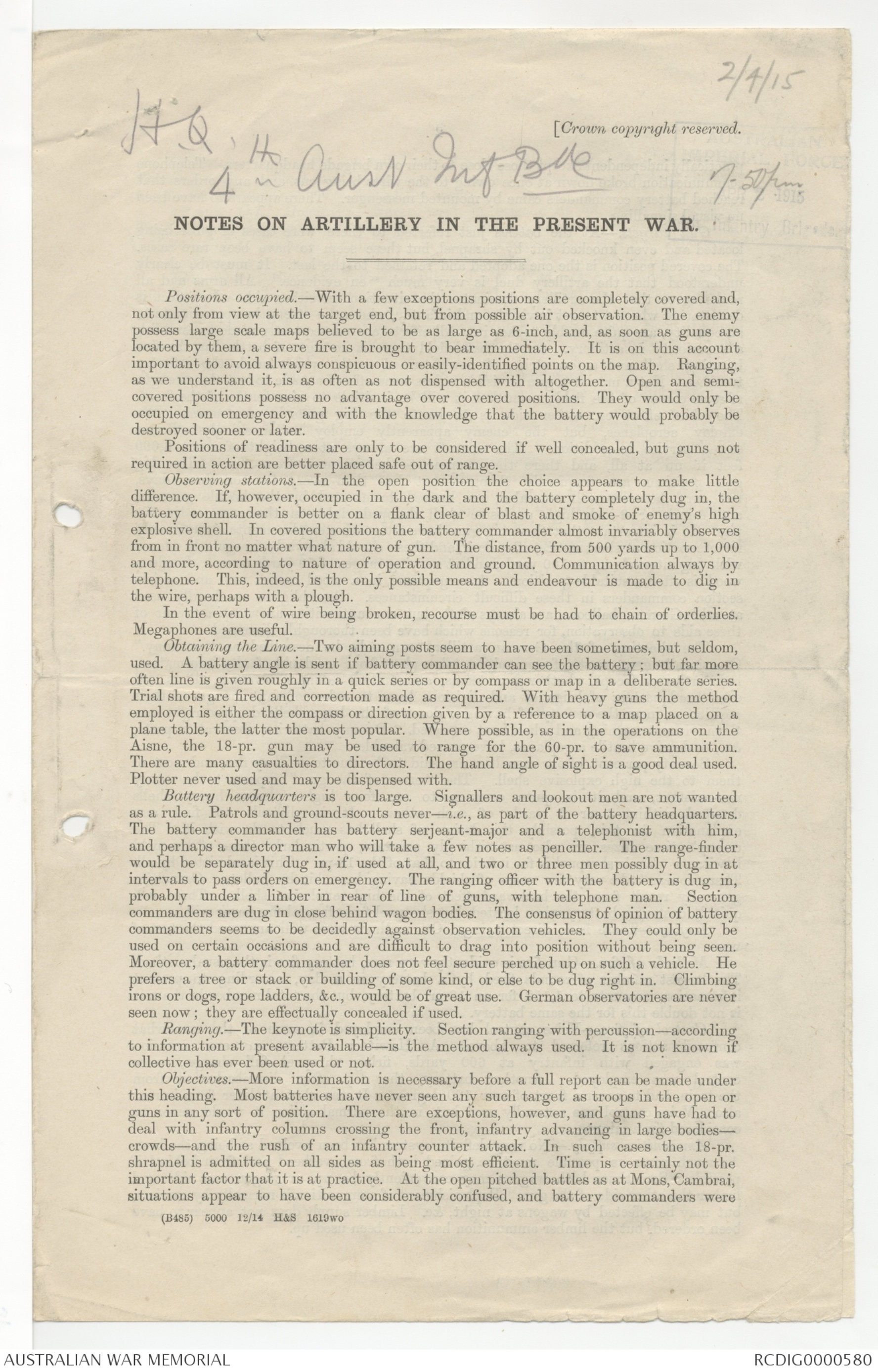

2/4/15

[Crown copyright reserved.

H.Q.

4th Aust Inf. Bde. 7.50pm

NOTES ON ARTILLERY IN THE PRESENT WAR.

Positions occupied.—With a few exceptions positions are completely covered and,

not only from view at the target end, but from possible air observation. The enemy

possess large scale maps believed to be as large as 6-inch, and, as soon as guns are

located by them, a severe fire is brought to bear immediately. It is on this account

important to avoid always conspicuous or easily-identified points on the map. Ranging,

as we understand it, is as often as not dispensed with altogether. Open and semi-

covered positions possess no advantage over covered positions. They would only be

occupied on emergency and with the knowledge that the battery would probably be

destroyed sooner or later.

Positions of readiness are only to be considered if well concealed, but guns not

required in action are better placed safe out of range.

Observing stations.—In the open position the choice appears to make little

difference. If, however, occupied in the dark and the battery completely dug in, the

battery commander is better on a flank clear of blast and smoke of enemy’s high

explosive shell. In covered positions the battery commander almost invariably observes

from in front no matter what nature of gun. The distance, from 500 yards up to 1,000

and more, according to nature of operation and ground. Communication always by

telephone. This, indeed, is the only possible means and endeavour is made to dig in

the wire, perhaps with a plough.

In the event of wire being broken, recourse must be had to chain of orderlies.

Megaphones are useful.

Obtaining the Line.—Two aiming posts seem to have been sometimes, but seldom,

used. A battery angle is sent if battery commander can see the battery; but far more

often line is given roughly in a quick series or by compass or map in a deliberate series.

Trial shots are fired and correction made as required. With heavy guns the method

employed is either the compass or direction given by reference to a map placed on a

plane table, the latter the most popular. Where possible, as in the operations on the

Aisne, the 18-pr. gun may be used to range for the 60-pr. to save ammunition.

There are many casualties to directors. The hand angle of sight is a good deal used.

Plotter never used and may be dispensed with.

Battery headquarters is too large. Signallers and lookout men are not wanted

as a rule. Patrols and ground-scouts never—i.e., as part of the battery headquarters.

The battery commander has battery sergeant-major and a telephonist with him,

and perhaps a director man who will take a few notes as a penciller. The range-finder

would be separately dug in, if used at all, and two or three men possibly dug in at

intervals to pass orders on emergency. The ranging officer with the battery is dug in,

probably under a limber in rear of line of guns, with telephone man. Section

commanders are dug in close behind wagon bodies. The consensus of opinion of battery

commanders seems to be decidedly against observation vehicles. They could only be

used on certain occasions and are difficult to drag into position without being seen.

Moreover, a battery commander does not feel secure perched up on such a vehicle. He

prefers a tree or stack or building of some kind, or else to be dug right in. Climbing

irons or dogs, rope ladders, &c., would be of great use. German observatories are never

seen now; they are effectually concealed if used.

Ranging.—The keynote is simplicity. Section ranging with percussion- according

to information at present available—is the method always used. It is not known if

Collective has ever been used or not.

Objectives.—More information is necessary before a full report can be made under

this heading. Most batteries have never seen any such target as troops in the open or

guns in any sort of position. There are exceptions, however, and guns have had to

deal with infantry columns crossing the front, infantry advancing in large bodies—

shrapnel is admitted on all sides as being most efficient. Time is certainly not the

important factor that it is at practice. At the open pitched battles as at Mons, Cambrai,

situations appear to have been considerably confused, and battery commanders were

(B485) 5000 12/14 H&S 1619wo

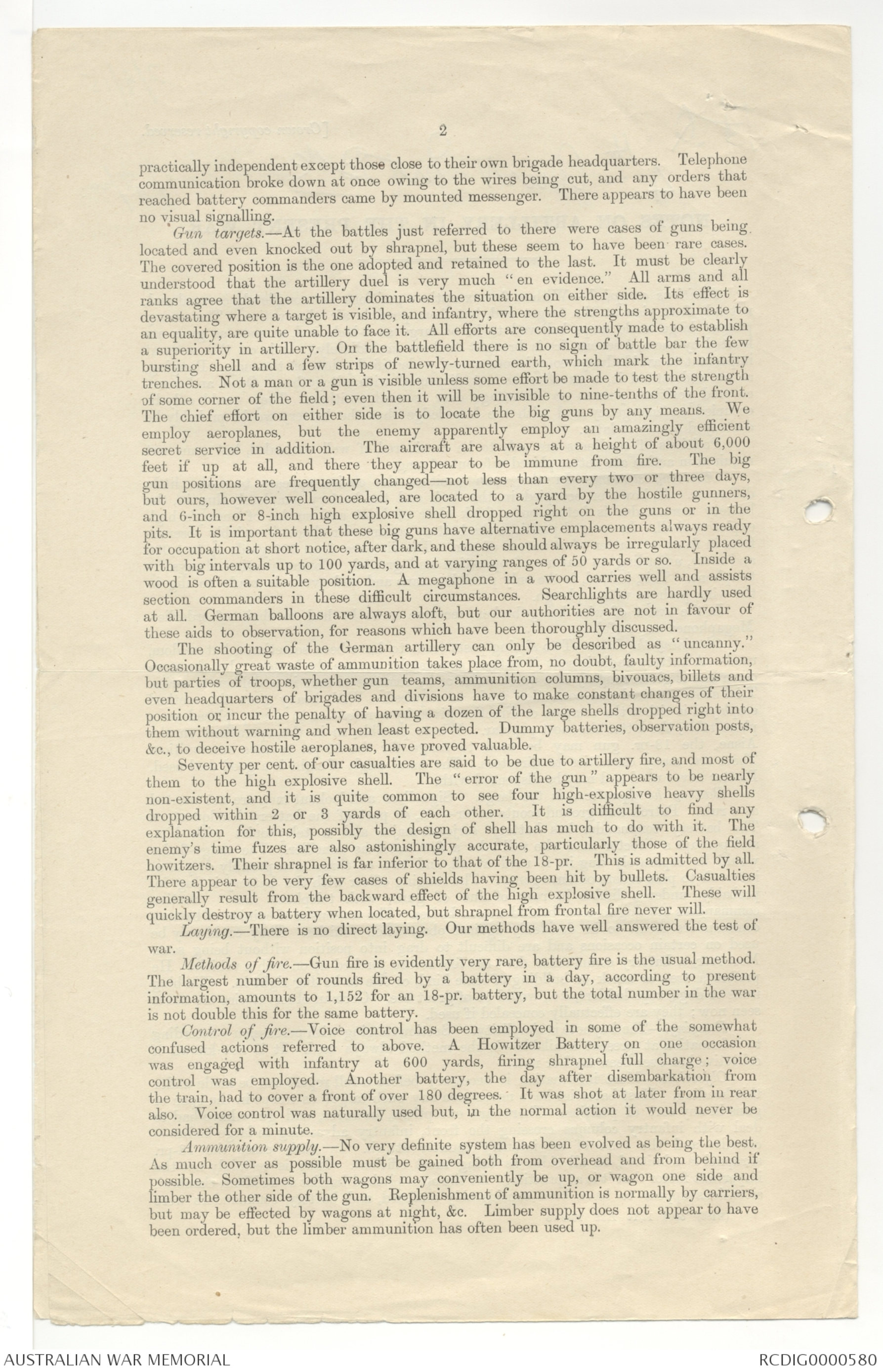

2

practically independent except those close to their own brigade headquarters. Telephone

communication broke down at once owing to the wires being cut, and any orders that

reached battery commanders came by mounted messenger. There appears to have been

no visual signalling.

Gun targets.—At the battles just referred to there were cases of guns being

located and even knocked out by shrapnel, but these seem to have been rare cases.

The covered position is the one adopted and retained to the last. It must be clearly

understood that the artillery duel is very much " en evidence." All arms and all

ranks agree that the artillery dominates the situation on either side. Its effect is

devastating where a target is visible, and infantry, where the strengths approximate to

an equality, are quite unable to face it. All efforts are consequently made to establish

a superiority in artillery. On the battlefield there is no sign of battle bar the few

bursting shell and a few strips of newly-turned earth, which mark the infantry

trenches. Not a man or a gun is visible unless some effort be made to test the strength

of some corner of the field; even then it will be invisible to nine-tenths of the front.

The chief effort on either side is to locate the big guns by any means. We

employ aeroplanes, but the enemy apparently employ an amazingly efficient

secret service in addition. The aircraft are always at a height of about 6,000

feet it up at all, and there they appear to be immune from fire. The big

gun positions are frequently changed—not less than every two or three days,

but ours, however well concealed, are located to a yard by the hostile gunners,

and 6-inch or 8-inch high explosive shell dropped right on the guns or in the

pits. It is important that these big guns have alternative emplacements always ready

for occupation at short notice, after dark, and these should always be irregularly placed

with big intervals up to 100 yards, and at varying ranges of 50 yards or so. Inside a

wood is often a suitable position. A megaphone in a wood carries well and assists

section commanders in these difficult circumstances. Searchlights are hardly used

at all. German balloons are always aloft, but our authorities are not in favour of

these aids to observation, for reasons which have been thoroughly discussed.

The shooting of the German artillery can only be described as

"uncanny."

Occasionally great waste of ammunition takes place from, no doubt, faulty information,

but parties of troops, whether gun teams, ammunition columns,

bivouacs, billets and

even headquarters of brigades and divisions have to make constant changes of their

position or incur the penalty of having a dozen of the large shells dropped right into

them without warning and when least expected. Dummy batteries, observation posts,

&c., to deceive hostile aeroplanes, have proved valuable.

Seventy per cent. of our casualties are said to be due to artillery fire, and most of

them to the high explosive shell. The "error of the gun"

appears to be nearly

non-existent, and it is quite common to see four high-explosive heavy shells

dropped within 2 or 3 yards of each other. It is difficult to

find any

explanation for this, possibly the design of shell has much to do with it. The

enemy's time fuzes are also astonishingly accurate, particularly those of the field

howitzers. Their shrapnel is far inferior to that of the 18-pr. This is admitted by all.

There appear to be very few cases of shields having been hit by bullets. Casualties

generally result from the backward effect of the high explosive shell. These will

quickly destroy a battery when located, but shrapnel from frontal fire never will.

Laying.—There is no direct laying. Our methods have well answered the test of

war.

Methods of fire.—Gun fire is evidently very rare, battery fire is the usual method.

The largest number of rounds fired by a battery in a day, according to present

information, amounts to 1,152 for an 18-pr. battery, but the total number in the war

is not double this for the same battery.

Control of fire.—Voice control has been employed in some of the somewhat

confused actions referred to above. A Howitzer Battery on one occasion was engaged with infantry at 600 yards, firing shrapnel, full charge ; voice

control was employed. Another battery, the day after disembarkation from

the train, had to cover a front of over 180 degrees. It was shot at later from in rear

also. Voice control was naturally used but, in the normal action it would never be

considered for a minute.

Ammunition supply.—No very definite system has been evolved as being the best.

As much cover as possible must be gained both from overhead and from behind if

possible. Sometimes both wagons may conveniently be up, or wagon one side and

limber the other side of the gun. Replenishment of ammunition is normally by carriers,

but may be effected by wagons at night, &c. Limber supply does not appear to have

been ordered, but the limber ammunition has often been used up.

3

Corrector.—Officers do not sufficiently use the table on page 164, Field Artillery

Training. The cardinal fault of our shooting would appear to be bursting shrapnel

too short ; the same applies to that of the enemy.

4.5-inch Q.F. Howitzers.—Never used in brigade at all, often by sections.

Time shrapnel ranging with the howitzer is believed not to have been used at all.

60-pr. B.L. has been invaluable. Economy of ammunition is of first importance.

It can sometimes be attained by making use of the 18-pr. for ranging purposes.

Entrenching.—Types in “Field Artillery Training “of pits, &c., are not sufficient.

Pits for men must be at least 4 feet deep and narrow, but many battery commanders prefer

the gun to be in a deep pit. It depends partly on the weather. It is desirable to have a

parapet in rear as well as in front on account of the high explosive shell. Solid overhead cover is also desirable as far as possible. The width, 13 feet, is not excessive in bad

ground or wet weather.

Map reading.— Map reading forms a very important detail in the daily work of

officers and non-commissioned officers, and any work out in the open after dark, and

should, therefore, be practised as much as possible.

Signalling.—The amount of work and time devoted to visual signalling have not

borne fruit in this war, but the more practice men have with the telephones and the

buzzer the better. An enormous amount is dependent on the telephones. Heavy

batteries go in for flag signalling with the Observation Officers.

On the whole peace training is proved to have been on the right lines, but from

what has been seen much more might be done with the advanced artillery officer.

The Germans are said to use him to a great extent. Much has also to be

learnt by artillery in their work in conjunction with aircraft.

Some notes on this

subject will form a heading in a later communication.

HEADQUARTERS,

BRITISH EXPEDITIONARY FORCE,

2nd October, 1914.

No. 1.

GENERAL ROUTINE ORDERS

By General Sir I. S. M. Hamilton, G.C.B., D.S.O., A.D.C.,

Commanding the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force.

GENERAL HEADQUARTERS,

2nd April, 1915.

ADJUTANT GENERAL’S BRANCH

1–Appointments.

(a) General Sir I. S. M. Hamilton, G.C.B., D.S.O., A.D.C., assumed command of the

Mediterranean Expeditionary Force on the 13th March, 1915.

(b) The following Officers were appointed to the General Headquarters of the

Mediterranean Expeditionary Force on the 13th March, 1915 :—

Chief of the General Staff … … … Major-General W. P. Braithwaite, C.B.

General Staff Officers—1st Grade

(Lieut.-Colonel M. C. P. Ward, R.A.

(Lieut.-Colonel W. de L. Williams, D.S.O., Hampshire Regt.

2nd Grade

(Major C. G. Fuller, P.E.

(Capt. C. F. Aspinall, R. Munster Fus.'

3rd Grade

(Major H. F. L. Grant, R.A.

(Capt. E. B. Powell, Rifle Brigade

(Capt. G. P. Dawnay, D.S.O., M.V.O.

(Capt. C. A. Bolton, Manchester Regt.

PERSONAL STAFF.

A.D.C.s to G.O.C.

(Capt. S. H. Pollen, R. of O.

(Lieut. Hon. G. St. J. Brodrick, Surrey Yeomanry.

A.D.C. to C.G.S. … … … 2nd-Lieut. V. A. Braithwaite, Somerset L.I.

Camp Commandant … … … Major J. S. S. Churchill, Oxfordshire Yeomanry.

Attached … … … … … Capt. O. C. Williams.

(c) The following Officers were appointed to the General Headquarters on the 17th March,

1915 :—

ADJUTANT GENERAL'S BRANCH.

Deputy Adjutant General … … … … Brig.-General E. M. Woodward.

Assistant Adjutant General … … … Lieut.-Colonel H. L. N. Beynon, R.A.

Deputy Assistant Adjutant General ... … Major T. S. Cox, Indian Army.

Deputy Assistant Adjutant General … … Capt. A. F. Egerton, D.S.O., R. of 0.

Staff Captain … … … … Capt. D. M. McLeod, N. Staff. Regt.

QUARTER MASTER GENERAL'S BRANCH.

Deputy Quarter-master General … … … Brig.-General S. H. Winter..

Assistant Quarter-master General … … Lieut.-Colonel L. R. P. Beadon, A.S.C.

Deputy Assist. Quarter-master General … Major E. F. O. Gascoigne, D.S.O., R. of O.

Deputy Assist. Quarter-master General … Capt. F. P. Dunlop, Worcester Regt.

Attached to General Headquarters

(Brig. -General R. W. Fuller, R.A.

(Brig.-General R. N. Roper, R.E.

Liaison Officer … … … … … Capt. C. de Putron, Lancashire Fus.

Interpreters

(Major W. H. Salmon, R. of 0.

(Capt. H. A. Bros, R.A.

(2nd-Lieut. E. J. Riches, R.A.

Censor … … … … … … … … … Capt. W. Maxwell.

[P.T.O.]

3rd ECHELON.

Assistant Adjutant General … … … … Colonel T. E. O'Leary, C.B.

Deputy Assistant Adjutant General … … Major E. W. Margesson, R. of 0.

Deputy Assistant Adjutant General … Major C. P. Scudamore, D.S.O., R. of O.

Staff Captain … … … … … Capt. H. C. Moffat, R. of 0.

Principal Chaplain … … … … … Rev. A. C. Hordern.

Veterinary Officer … … … … … … Lieut. F. Chambers.

Attached to GS.

(Lieut. T. O. Nicholas.

(Major A. Delacombe.

(d) The following Officers were appointed to the General Headquarters on the 18th March,

1915 :—

General Staff Officer—2nd Grade … Lieut.-Colonel C. H. M. Doughty-Wylie, C.B.,

C.M.G., R. Welsh Fus.

3rd Grade … … … … … Capt. W. H. Deedes, K.R.R.C.

Special Service Officer … … … Capt. I. M. Smith, Somerset L.I.

(e) - The following Officer was appointed to the General Headquarters on the 17th March,

1915 :—

Provost Marshal … … … … Capt. Hon. C. C. Bigham, C.M.G.

(f) The following Officer was appointed to the General Headquarters, 3rd Echelon, on the

28th March, 1915 :—

Commandant of Militay Prisons in the Field ... Capt. H. D. Carlton, Royal Scots.

(g) The following Officers were appointed to Headquarters of Administrative Services and

Departments of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force, on the 17th March, 1915 :—

Director of Army Signals ... Lieut.-Colonel M. G. E. Bowman-Manifold, D.S.O., R.E.

Assistant Director of Supplies and Transport … … Major G. F. Davies, A.S.C.

Assistant Director of Transport … … … Major W. M. Parker, A.S.C.

Deputy Director of Ordnance Stores … … … Colonel P. A. Bainbridge.

Assistant Commissary of Ordnance … … … Lieut. L. D. Henderson.

Director of Works … … … … Brig. -General G. S. MoD. Elliot.

Director of Medical Services … … … Surgeon General W. E. Birrell.

Deputy Director of Medical Services … … Lieut.-Colonel A. E. C. Keble.

Deputy Assistant Direstor of Medical Services … … Capt. E. N. N. Paine.

Director of Veterinary Services … … … Lieut.-Colonel E. Taylor.

Chief Paymaster … … … … … Lieut.-Colonel J. Armstrong.

Army Pay Department

(Capt. W. P. Mackenzie.

(Lieut. H. W. H. Elliot.

( “ S. A. Godfrey.

( “ A. S. N. Brooke.

( “ H. S. C. Roy.

( “ L. H. Carter.

2–Field Return. (Army Form B 213).

With reference to F.S.R., Part 2, para. 132-1, Officers Commanding will at once transmit

A.F. B 213 for every unit to the A.A.G., General Headquarters, 3rd Echelon.

This return will, subsequently, be transmitted weekly as laid down in the above mentioned para.

E. M. WOODWARD, Brigadier-General,

D.A.G., M.E.F.

QUARTERMASTER-GENERAL'S BRANCH.

3–Transport.

Units at the Base will utilize their regimental transport as for as possible for all purposes.

Should further transport be required Units at Mustapha will requisition on the Transport Officer

there. Units at all other camps will requisition on Officer i/c Transport, Wardian Camp.

S. H. WINTER, Brigadier-General,

D.Q.M.G., M.E.F.

Printed at General Headquarters by Printing Section, R.E.

H.Q.

4th Aust Inf Brigade

AUSTRALIAN

IMPERIAL FORCE

7-50pm

APR 2 1915

4th Infantry Brigade.

FURTHER NOTES ON ARTILLERY IN THE PRESENT WAR.

Speaking generally, it may be said that Field Artillery Training in the light of

experiences up to date requires remarkably little alteration. Both the general

principles laid down and the detailed instructions given have been proved to be correct,

with hardly any exceptions.

Some notes on various sections of the Training Manual follow :—

Chapter VII., Section 146.—Concealment assumes greater importance than ever.

It is not merely desirable but essential, and in modern war concealment means cover

from view from the enemy's observers, whether on the ground or in the air. In addition

tọ concealment when in position the approach to the position must also be hidden from

air observers. If hostile aeroplanes are observed guns must remain perfectly still along

the edge of woods, &c., where they may escape observation ; during movement there

must be look-out men on the watch for the approach of the enemy's aircraft.

Owing to the great height at which these fly, i.e., about 6,000 to 7,000 feet, they

cannot usually be detected unless first heard approaching. The look-out man should

therefore be placed where the approach of an aeroplane would be audible, e.g., away

from roads. It is possible to distinguish between the enemy's and friendly machines

by means of the coloured designs painted on the under plane. The French have

red, white and blue concentric rings, and the English a union jack in addition to the

rings. The German machines show a black cross almost similar to a Maltese cross

It is usual when possible to stop firing when the enemy's aeroplane is overhead

until it disappears owing to the importance of keeping

gun positions secret. When

they are located the enemy do not seem to find much difficulty in shelling them and

inflicting casualties both on personnel and material.

Much may, however, be done to mislead the enemy's air observers by the use of

partially concealed emplacements and puffs to represent the flash and report of guns.

These must, however, be sparingly used, and, as a rule, be under the direction of the

Divisional Artillery Headquarters.

It is quite as important to conceal completely wagon and gun teams as the guns

themselves, and they are best placed, if possible out of range altogether. Where it is

not possible to conceal them, their position must be changed directly it has been located

by an observer, if casualties are to be avoided.

Even when positions are effectually hidden it must be remembered that if the

locality can be described accurately by spies, just as effective fire can be brought to

bear as if the position had been plainly visible. The chief considerations, then—given

concealment—should be

(1.) The selection of a position difficult to locate accurately on a map.

(2.) The occupation of the position in such a way as to increase the difficulty of

hitting any gun or emplacement, viz., by placing guns at wide and irregular

intervals, and even at varying ranges.

Section 147. Economy of force.—The necessity for this has been well exemplified

according to all reports and personal observation. The enemy's guns and observing

stations are so well concealed and so constantly changed that it is nearly always

advisable to reserve guns to deal with later contingencies. That this is not sufficiently

practised is perhaps due to peace training, but it has assumed great importance in war,

and great stress must be laid on it during training. The labour of taking up a position

and entrenching is great, whereas, often, it may have been completed only just before

a change is shown to be desirable.

The bigger the calibre of the gun the more important this factor of economy. If

howitzers are required for a task, four may often be sufficient, or even two ; while heavy guns should hardly ever be in larger units than sections.

(B510) 5000 12/14 H&S 1620wo

2

The bigger the calibre the greater also the difficulty of the ammunition supply.

It may therefore sometimes be advisable to attach an 18-pr. gun to heavier

natures to assist in ranging and registering. It is true this introduces complications,

but nevertheless it may sometimes be worth while.

In modern battle fronts the extent of ground is so great that the character of the

country will vary in different parts of the position. At the battle of the Aisne the

British Corps were extended over a front of some 15 miles or even more. In some

portions only could howitzers be profitably utilized, while in others guns could do all that was required.

Section 148. Protection, sub-paragraph 5.—The carrying of rifles on wagons in

the artillery appears to have been justified by their having been made use of on more

than one occasion.

Section 149. Intercommunication.—Communications are perhaps

the greatest

difficulty that units have to contend with owing to the almost exclusive use of the

telephone. Flag signalling is rare, but has been used both by field and heavy artillery

on suitable occasions when there was no chance of observation by the enemy.

Buzzing on the telephone is very much resorted to and is invaluable.

It was perhaps not sufficiently recognized in the Royal Artillery in peace how

much training is required to keep telephone communication uninterrupted. The difference

in the working of the telephones by the Royal Engineers and Royal Artillery to some extent

fail.

The necessity for an efficient telephone service cannot be too strongly impressed

on those now training. Men require much training in speaking, which is an acquired

art, as well as in keeping the instruments and line in good working order. Casualties

amongst these men, who do not hesitate to go out and repair lines under the hottest

fire, are bound to occur, and there should therefore be plenty under training. Every

telephonist must know the Morse code and be able to use the buzzer.

When laid out the wire should be dug in if time permit, as such frequent interruptions

occur from the wire being cut. The digging in is best arranged by ploughing a

furrow with an ordinary plough, if available, and there are many about in the fields.

The lamp is useful, but it alsorequires highly skilled signallers.

Megaphones are useful. Section commanders sometimes use them to make themselves

heard above the noise of bursting shell

Section 163A. Artillery in wood fighting.—Most guns in the recent battle have

been inside or just on the edge of woods. If woods did not accommodate the guns,

young trees were cut down and planted around the batteries so as to screen them. In

the winter, except where firs are available, these methods will not, perhaps, be so

effective. Wagon teams were always concealed in woods if possible.

Artillery will do well to keep clear of all villages, if within range of hostile guns.

Villages aid the location of targets by description, and are apt to draw shell fire.

It may be well here to emphasize the necessity of much practice with maps, e.g.,

locating places in strange country, using the map for obtaining range, line and angle of

sight.

Section 164. Night operations.—The chief work to be carried out at night is the

occupation of positions and entrenching. Practice in peace training is all important.

Ammunition is constantly replenished at night, and changes of

gun positions or the

positions of the teams are nearly always effected at night. Suitable artificial light is a

great help. The showing of lights would generally be unobjectionable if positions are

well concealed from the target direction.

Firing by night is more indulged in by the enemy than ourselves, but it has been

attempted on certain occasions against targets to which the range had been ascertained

by day. The enemy make frequent endeavours to shell villages or buildings known to

be occupied by our troops after dark, but the effect would not appear commensurate

with the expenditure of ammunition ; at least, we should not consider it so.

Chapter VIII., Section 181. Reconnaissance.—From the information available on

this subject, it would seem that the battery commanders have had more tactical control

of their units than is contemplated by Field Artillery Training. This is due mainly to

the difficulty of communication in the field. Battery commanders have certainly very

often done the whole of their reconnaissance, making their choice of position on the

information and instructions received from brigade headquarters. Space appears for

the most part not to be confined, but, since batteries are always concealed, observing

stations are nearly always distant. No account is taken of the danger angle. The

3

"position in observation" is much used, but the "position in readiness" finds no place

in the modern battle.

Section 186. Allotting objectives is effected either by the map or by personally

pointing out localities visible from observing stations.

A howitzer brigade is seldom used as such, and howitzer batteries are further much

split up into sections, or even single guns on occasions.

Chapter IX., Section 192. Reconnaissance of a position.—Complete concealment

in the reconnaissance and in the approach to and occupation of the observing station is

absolutely essential. A background is necessary to the observing station, and there

should be as few people present there as possible. All required must be dug in to

complete cover, and a view of the battery is likely to be impossible. The use of observation

wagons would seldom be desirable or possible, except sometimes in a flat country

where it is necessary to raise the eye of the observer. But it should then be remembered

that the shield of the observatory is no protection against high explosive shell. A

battery commander would be as secure, on the whole, in a tree as raised up on a ladder

provided with a shield, and at the same time better supported.

The first object of the reconnaissance is, contrary to paragraph 3 of this section,

almost always a position for the guns that will defy discovery as long as possible.

The position of the observation station is subservient, being selected as occasion demands,

and is normally in front of the guns.

It is hardly ever necessary to mark the line of fire with aiming posts. The line is

generally obtained roughly from the map and a trial shot fired from which to make a

correction.

Section 193. Methods of occupying a position.—In the above circumstances the

"special method" is more often followed than the ordinary.

Occupations of position by night require special treatment, the method being

adapted to circumstances.

Whatever the method or whatever the position, digging should commence at the

earliest possible moment.

Section 195. Advance for action.—This section requires slight modifications in

accordance with the above. The wagon line should be as far away from the battery as

possible, convenient with ammunition supply, which will probably be by ammunition

carriers by hand, or else take place after dark.

Section 196. To come into action.—Batteries may require to have either both

wagons in action at the same time or to have the wagon on one side of the gun and

the limber on the other, if reliance is placed on the vehicles to afford cover. Normally,

however, cover is obtained by digging.

Section 198. Laying out the line of fire.—Method of obtaining the line has been

alluded to in the remarks on Section 192, the governing fact is, of course, that the

battery is not likely to be visible from the observing station.

The compass is most

useful. Maps are even more so.

The procedure adopted is somewhat as follows :—

Place the map on a plane table, or on some flat surface, in the battery. Set

the map accurately either by means of two known points located on the map or by

the compass, taking into account the magnetic variation.

The battery commander measures with a protractor the angle between the target

and some object shown on the map, such as a church, and telephones the

object selected to the battery leader, who is thus enabled to fix a line on the map

by means of two pins, viz. :—the line battery—church.

Suppose the battery commander orders the line of fire 10 degrees right of the

fixed line, the battery leader will lay his director set at 10 degrees right on the

line joining the two pins in his map. The director is then swung round to zero,

when it will be in the required line of fire. Individual angles may then be given

to guns or an aiming point selected in the ordinary way.

When working in conjunction with aircraft the line should be obtained by clamping

the director on the aeroplane when immediately over the target. A good method of

signalling when the machine is over the target is that adopted by the enemy, whose

observers fire a small smoke ball which shows very clearly, and could be laid easily on

with a director.

Sections 203–205. Co-operation of aircraft.—Air observation is greatly used both

by ourselves and the enemy.

Both the battery commander and observer are provided with a map, the larger

scale the better, and the position of target on the map is given by the observer. The

(1620)

4

battery then lays out the line by the aid of the map and observations are signalled

back after each round fired. Effective fire can be reached within some 10 minutes of

the first round fired.

The first necessity of any system is speed, on account of the exposure of the airman

to hostile fire throughout the operation.

This system is slow, and experiments have been undertaken with a view to devising

other systems. (See Appendix I.)

Wireless telegraphy has been found the quickest and most satisfactory system of

communication. The use of Very's lights is resorted to on occasions when wireless

telegraphy is not available, and some fair results are believed to have been obtained with

them.

The German method of giving the line to the battery by firing a smoke ball over

the target is most effective: it appears to be only a part of a somewhat elaborate

system. The resulting fire is generally most accurate.

Section 207. Ranging.—Section ranging is the method that is employed as being

the simplest, with percussion or long corrector, the former for choice, owing to there being

less chance of error. False crests do not abound in the north-east of France. The

general aspect of the country is not unlike Wiltshire, and often remarkably like Salisbury

Plain. There is a bigger sprinkling of woods, and they are larger. The features are

bolder and the valleys wider and deeper. Time shrapnel ranging, which is so suitable for

overcoming the difficulties met with where there are many small dips and depressions,

is not apparently required by the conditions prevailing.

Fuzes have sometimes burst at irregular heights. This is usually due to one of the

following reasons—

(1.) Sights getting slightly out of adjustment.

(2.) Want of exact precision in the use of the gears when adjusting sights.

(3.) Development of increased play in equipment

(4.) Bubble not being accurately centred before firing

The importance of paying attention to these points must be impressed on all concerned

with the training.

The heights of burst given in the Manual must not be exceeded if fire is to be

effective.

Section 215. Searching.—Searching is much resorted to, in spite of the

expenditure of ammunition entailed. On the Aisne the lie of the land in the enemy's

position was soon fairly well known and constant reports sent in from aeroplanes

increased the value and effect of searching.

Section 216. Sweeping.—Sweeping has been employed on at least one occasion

and the effect appeared to be satisfactory. The method adopted was an adaptation of

that laid down in this section, the object being to avoid a regularity of fire against

which the hostile detachments can easily protect themselves.

Section 219. To register a zone.—Cases of registering a zone by single batteries,

so far as is known, have been rare. Either targets have been presented by bodies of

troops moving in an area in such a way that they were capable of being dealt with by

following them up as they moved, with shrapnel fire, or else the artillery have been

employed in shelling certain held portions of a position which may or may not be visible

from the observing station.

Registration would seem to have been more the task of the artillery of a division

as a whole, that is to say, a division is made responsible for a certain zone and all the

portions in that zone are ranged on, watched and shelled as required by the various

batteries concerned, under divisional arrangements.

Sections 220–226. Objectives.—The artillery duel appears to have returned, and

one of the principal tasks of our artillery has been the silencing of the enemy’s guns.

The destruction or effectual shelling of an observing station requires all the skill

of an experienced battery commander ; similarly, infantry shelter trenches require the

most accurate fire to be brought against them, but for each case such as those

mentioned there will probably be many where it is required to bring fire to bear on

an area behind a ridge, a wood, a village, a ravine, or to keep quiet guns posted in an

invisible locality. In such cases accuracy in the service of the gun is as necessary as

ever, but extreme accuracy of observation loses some of its importance.

A few batteries have made use of walls of fire, and at Caudry , in August,

batteries built walls of fire which held up all movement for a considerable length of time.

Indeed, the wall was impenetrable so long as it lasted.

In dealing with situations similar to those at the Aisne, where the opposing

infantry trenches were within a few hundred yards of each other and the guns of either

Jacqueline Kennedy

Jacqueline KennedyThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.