Charles E W Bean, Diaries, AWM38 3DRL 606/119/1 - Photostats - Part 4

[*D12

Page 132*]

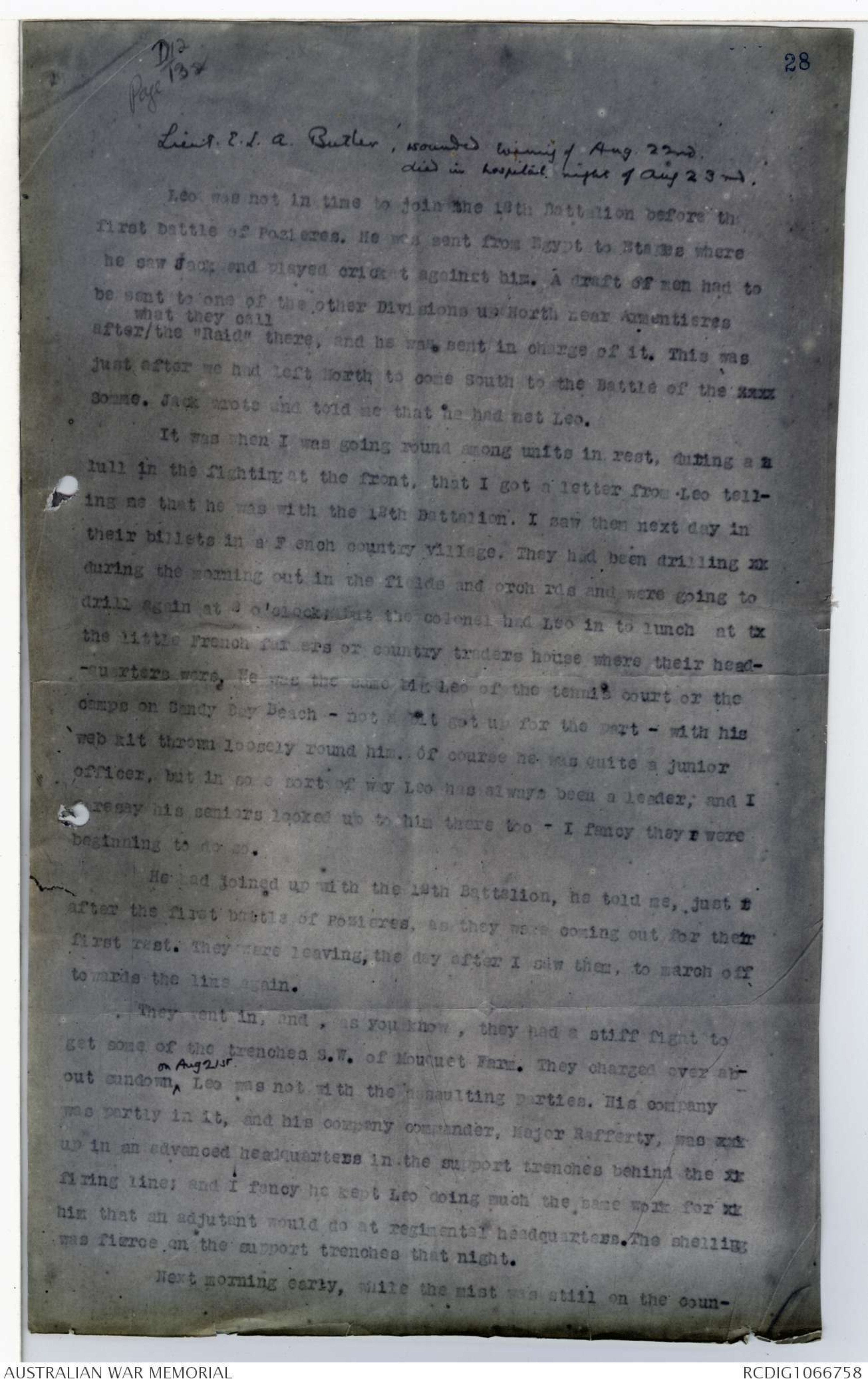

28

Lieut. E.L.A. Butler, wounded evening of Aug. 22nd

died in hospital night of Aug 23rd.

Leo was not in time to jointhe 18th Battalion before the

first battle of Pozieres. He was sent from Egypt to Etaples where

he saw Jack and played cricket against him. A draft of men had to

be sent to one of the other Divisions up North near Armentieres

after ^what they call the "Raid" there, and he was sent in charge of it. This was

just after we had left North to come South to the Battle of the xxxx

Somme. Jack wrote and told me that he had met Leo.

It was when I was going round among units in rest, during a x

lull in in the fighting at the front, that I got a letter from Leo telling

me that he was with the 12th Battalion. I saw them next day in

their billets in a French country viilage. They had been drilling xx

during the morning out in the fields and orchards and were going to

drill again at 2 o'clock; but the colonel had Leo in to lunch at xx

the little French farmers or country traders house where their headquarters

were. he was the same big Leo of the tennis court or the

camps on Sandy Bay Beach - not a bit got up for the part - with his

web kit thrown loosely round him. Of course he was quite a junior

officer, but in some sort of way Leo has always been a leader; and I

daresay his seniors looked up to him there too - I fancy they r were

beginning to do so.

He had joined up with the 12th Battalion, he told me, just x

after the first battle of Pozieres, as they were coming out for their

first rest. They were leaving the day after I saw them, to march off

towards the line again.

They went in, and, as you know, they had a stiff fight to

get some of the trenches S.W. of Mouquet Farm. They charged over about

sundown ^on Aug 21st, Leo was not with the assaulting parties. His company

was partly in it, and his company commander, Major Rafferty, was xxx

up in an advanced headquarters in the support trenches behind the xx

firing line; and I fancy he kept Leo doing much the same work for xx

him that an adjutant would do at regimental headquarters. The shelling

was fierce on the support trenches that night.

next morning early, while the mist was still on the country

[*D12

132*]

(2)

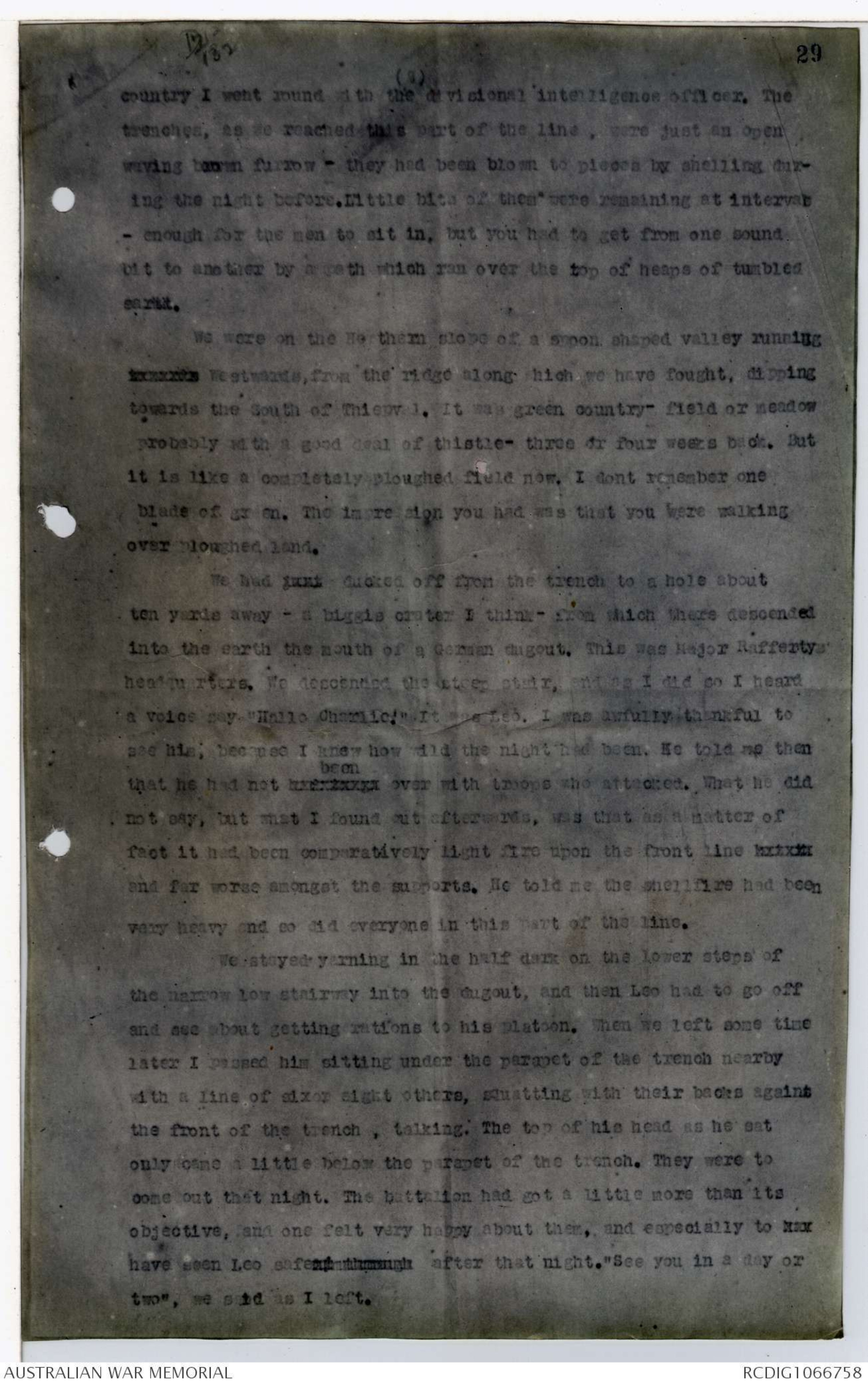

29

I went round with the divisional intelligence officer. The

trenches, as we reached this part of the line, were just an open

waving brown furrow - they had been blown to pieces by shelling during

the night before.Little bits of them were remaining at intervals

- enough for the men to sit in, but you had to get from one sound

bit to another by a path which ran over the top of heaps of tumbled

earth.

We were on the Northern slope of a spoon shaped valley runningxxxxxx Westwards, from the ridge along which we have fought, dipping

towards the South of Thiepval. It was green country - field or meadow

probably a good deal of thistle - three or four weeks back. But

it is like a completely ploughed field now. I dont remember one

blade of green. The impression you had was that you were walking

over ploughed land.

We had just ducked off from the trench to a hole about

ten yards away - a biggis crater I think - from which there descended

into the earth the mouth of a German dugout. This was Major Raffertys

headquarters. We descended the steep stair, and as I did so I heard

a voice say "hallo Charlie!" It was Leo. I was awfully thankful to

see him, because I knew how wild the night had been. He told me then

that he had not xxxxxxxx been over with the troops who attacked. What he did

not say, but what I found out afterwards, was that as a matter of

fact it had been comparatively light fIre upon the front line xxxx

and far worse amongst the supports. He told me the shellfire had been

very heavy so did everyone in this part of the line.

We stayed yarning in the half dark on the lower steps of

the narrow low stairway into the dugout, and then Leo had to go off

and see about getting rations to his platoon. When we left some time

later I passed him sitting under the parapet of the trench nearby

with a line of six or eight others, squatting with their backs against

the front of the trench, talking. The top of his head as he sat

only came a little above the parapet of the trench. They were to

come out that night. The battalion had got a little more than its

objective, and one felt very happy about them, and especially to xxx

have seen Leo safe xxxxxxxxxxxxx after that night. "See you in a day or

two", we said as I left.

[*D12

132*]

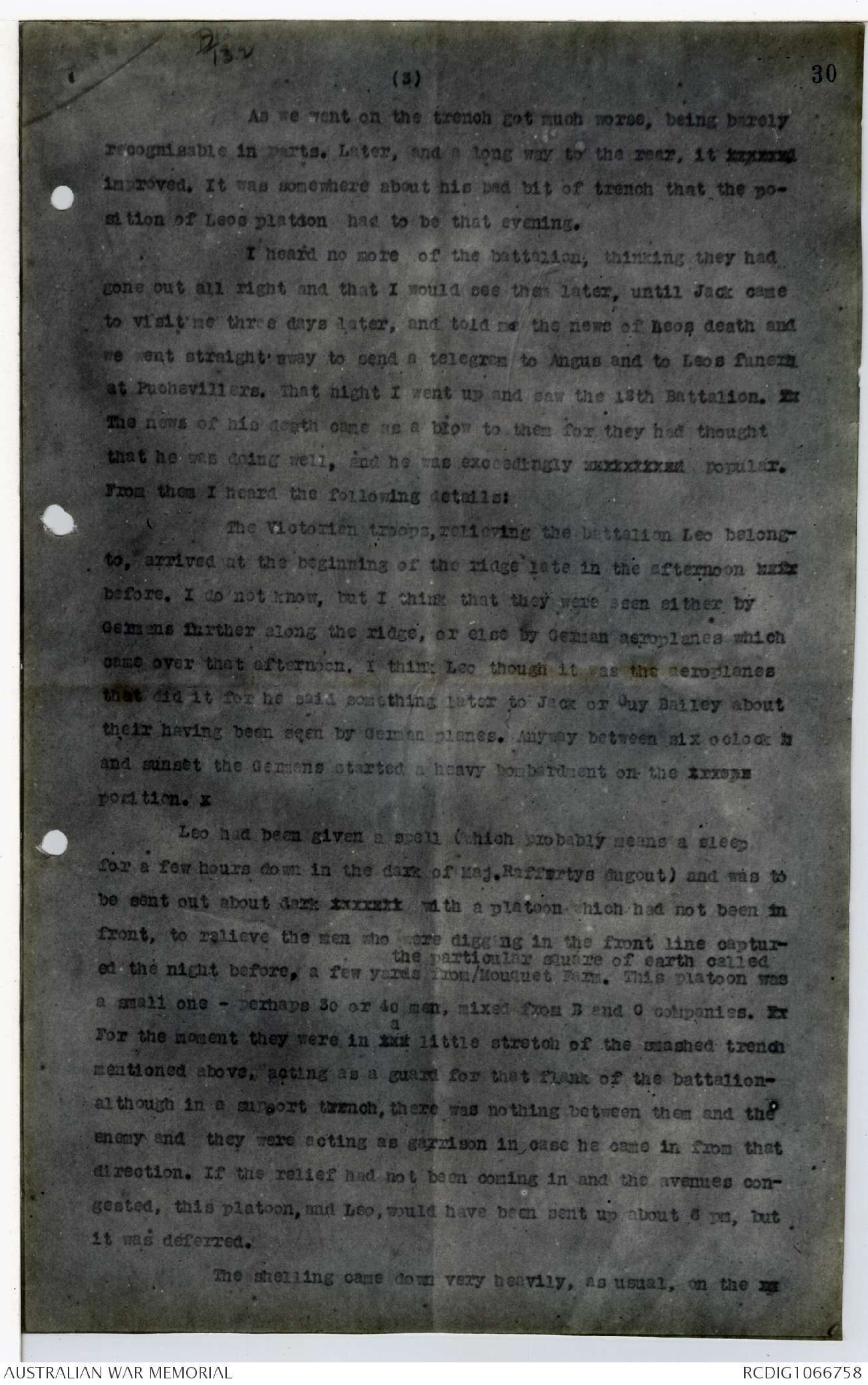

30

(3)

As we went on the trench got much worse, being barely,

recognisable in parts. Later, and a long way to the rear, it xxxxxx

improved. It was somewhere about his bad bit of trench that the position

of Leos platoon had to be that evening.

I heard no more of the battalion, thinking they had

gone out all right and that I would see them later, until Jack came

to visit me three days later, and told me the news of Leos death and

we went straight away to send a telegram to Angus and to Leos funeral

at Puchevillers. That night I went up and saw the 12th Battalion. xx

The news of his death came as a blow to them for they had thought

that he was doing well, and he was exceedingly xxxxxxxx popular.

From them I heard the following details:

The Victorian troops, relieving the Battalion Leo belong-

to, arrived at the beginning of the ridge late in the afternoon xxxx

before. I do not know, but I think that they were seen either by

Germans further along the ridge, or else by German aeroplanes which

came over that afternoon. I think Leo thought it was the aeroplanes

that did it for he said something later to Jack or Guy Bailey about

their having been seen by German planes. Anyway between six oclock x

and sunset the Germans started a heavy bombardment on the xxxxxx

position. x

Leo had been given a spell (which probably means a sleep

for a few hours down in the dark of Maj.Raffertys dugout) and was to

be sent out about dark xxxxxx with a platoon which had not been in

front, to relieve the men who were digging in the front line captured

the night before, a few yards from ^the particular square of earth called Mouquet Farm. This platoon was

a small one - Perhaps 30 or 40 men, mixed from B and C companies. Xx

For the moment they were in xxx a little stretch of the smashed trench

mentioned above, acting as a guard for that flank of the battalion -

although in a support trench, there was nothing between them and the

enemy and they were acting as garrison in case he came in from that

direction. If the relief had not been coming in and the avenues congested,

this platoon, and Leo, would have been sent up about 6 pm, but

it was deferred.

The shelling came down very heavily, as usual, on the xx

[*D12

Page 132*]

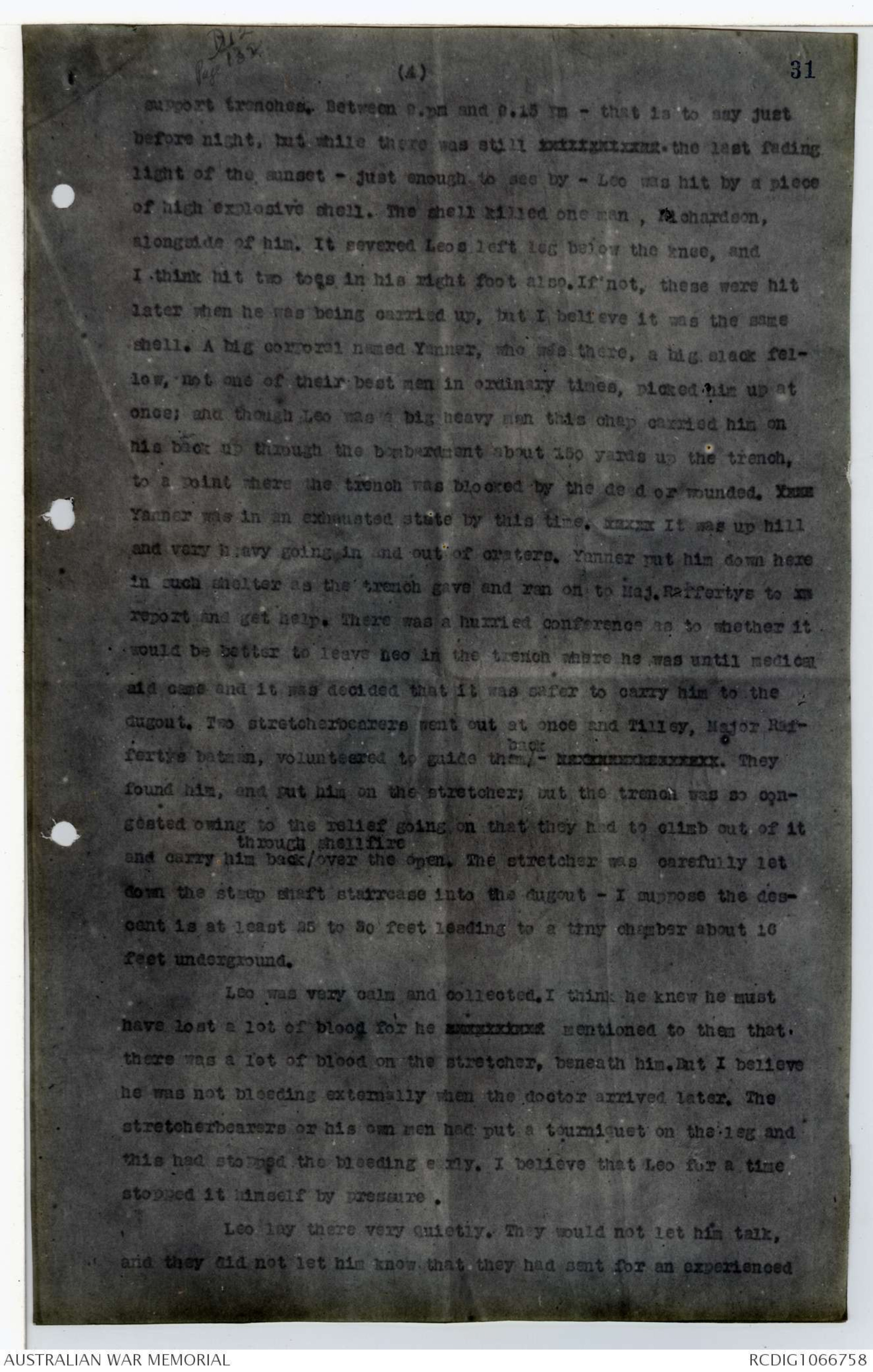

31

(4)

support trenches. Between 9. pm and 9.15 pm - that is to say just

before night, but while there was still xxxxxxxxxx - the last fading

light of the sunset - just enough to see by - Leo was hit by a piece

of high explosive shell. The shell killed one man, Richardson,

alongside of him. It severed Leos left leg below the knee, and

I think hit two toes in his right foot also. If not, these were hit

later when he was being carried up, but I believe it was the same

shell. A big corporal named Yanner, who was there, a big slack fellow,

not one of their best men in ordinary times, picked him up at

once; and though Leo was a big heavy man this chap carried him on

his back up through the bombardment about 150 yards up the trench

to a point where the trench was blocked by the dead or wounded. Xxx

Yanner was in an exhausted state by this time. xxxxx It was up hill

and very heavy going in and out of craters. Yanner put him down here

in such shelter as the trench gave and ran on to Maj.Raffertys to xx

report and get help. There was a hurried conference as to whether it

would be better to leave Leo in the trench where he was until medical

aid came and it was decided that it was safer to carry him to the

dugout. Two stretcherbearers went out at once and Tilley, Major Raffertys

batman, volunteered to guide them ^back - xxxxxxxxxxxxx . They

found him, and put him on the stretcher; but the trench was so congested

owing to the relief going on that they had to climb out of it

and carry him back ^through shell fire over the open. The stretcher was carefully let

down the steep shaft staircase into the dugout - I suppose the descent

is at least 25 to 30 feet leading to a tiny chamber about 16

feet underground.

Leo was very calm and collected. I think he knew he must

have lost a lot of blood for he xxxxxxxx mentioned to them that

there was a lot of blood on the stretcher, beneath him. But I believe

he was not bleeding externally when the doctor arrived later. The

stretcherbearers or his own men had put a tourniquet on the leg and

this had stopped the bleeding early. I believe that Leo for a time

stopped it himself by pressure.

Leo lay there very quietly. They would not let him talk,

and they did not let him know that they had sent for an experienced

[*D12

Page 132*]

32

(5)

A.M.C. man to come and see him. (They do not ask the doctor to come

up there as his job is at his aid post. There was a barrage of German

shell between the front line and the aid post and it was dangerous

to come through it.The doctor would not be expected in the front).

Leo told Rafferty as he lay there that all day he had felt that

something was going to happen to him. He had given Rafferty a couple

of pocket books, with a note as to what to do with his things (which

note is with his valuables and badges now, tied up with the two pocket

books exactly as Rafferty gave it to me.).

Somewhere about midnight there arrived at the dugout

Capt. Johnson, the doctor of the 12th Bn. He had been relieved andx

was free to go out of the line, the new battalions doctor having

taken his duties; but he came up himself. He gave Leo an opiate to

send him to sleep for a while. While the doctor was up there he

attended to a number of other wounded also. Leo did not want to be

attended to first - he asked to take his turn and that the doctor

should not attend to him while he had others to attend to.

The next difficulty was to get Leo carried back the very

long and dangerous journey from there to the advanced dressing

station, where the wounded are put into cars. About two miles back

they are put into Horse ambulances, which go another mile to the

dressing station, where xxxxxx dressings are looked at and left on or taken xx

off as appears necessary. The battalion stretcherbearers were utterly

worn out and Maj.Rafferty asked for two to be sent up from a field

Ambulance. I dont know whether these came or not. Anyway two worn

out regimental stretcherbearers volunteered to stay and carry him x

down as soon as daylight came. The stretcherbearers say that the

Germans will not snipe at them by day so long as they have the white

flag up - so that they could carry him ^straight over the open then only chancing

the shells which are generally easiest at that hour.

That is what they did. The battalion left at 3 in the morning

when the new battalion took over. The new battalion (24th) came

into the dugout and Capt. Williams of that battalion promised to have

Leo sent down as soon as it was light. Capt. Williams may know xxxxxx

something more - I have not seen him yet.

[*D12

Page 132*]

33

(6)

Capt. Johnson went back to the aid post, administering

injections to wounded men wherever he met them, and at daylight

went on to the advanced dressing station xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

to let them know Leo was coming and interest them. Leo passed

through the dressing station some time that day(August 23rd

Wednesday). He went on to hospital at Warloy, a village about

7 miles back, and later, after the operation, I think, to

Puchevillers. It may have been that he was operated on at

Puchevillers - Guy Bailey and Jack know all about that. I am a

little vague.xxxxx They had to take Leos left leg off at the hip.

Of course that is a most serious operation, but they say he seemed

to get through it well and his voice as strong. It was the loss of

blood, apparently, that made it so very dangerous. I believe the

circulation in his other leg had stopped and it would have been a x

question, had he lived, whether that leg too might not have had to

be amputated.

Jack tells me that when he saw Leo he said he was not

in pain but only very restless Restlessness would be a sign of the

loss of blood.

That is all that I heard as to the xxx. Leos men

and his commanding officer xxxx were very much attached to him. Maj

Rafferty told me: " Butler became attached to my company _C-when we

went from Pozieres the first time. He was new to us, but I soon

knew there was something in him by the way the men took to him. They

jumped at him, .at once: from the first moment he joined. He did not

seem to sharp in speech or action like most smart soldiers - he

spoke quietly and evenly, always the same; you learned to know and

appreciate that even manner of his.Leo - well he was well named;

there was something lionlike in him x - a grand man.

"He was only attached temporarily to C company in the first

place. He wanted to go to B company because his friends Sherwin and

others were there. The Colonel told him he would put him with us for

the present because we were short. Some days after he went to the xx

Colonel and reminded him of the request, 'and asked him not to

[*D12

page 132*]

34

(7)xxxx trouble about the transfer. He had decided to stay with "C" xx

company." He and Rafferty lived in the same billet in most of the

villages they stopped in. At Herrissert the major noticed him one

night ^sitting reading a small book.

"What, are you fond of poetry?" Rafferty asked.

"No, its a testament," Leo said. "I promised my mother

before I came away that I would read a little every day, and I

intend to keep that promise."

Guy Bailey was present, I think, when Leo died, at

11p.m. on Wednesday August 23rd, at xxxxxxxxxx Hospital

Allan Barton, a great friend of Angus at xxxxxxxx college, was there too.

Jack had seen him an hour before when he seemed to be doing well.

His funeral took place at the Puchevillers hospital cemetery at

the next afternoon. Major Ingram (who was also at the same hospital)

Guy Bailey, a youngster(also a medico) named Walker, Alan

Barton, Jack and myself were present. The grave is in the corner of

a wheatfield overlooking a wide undulating beautiful country, far

away from the guns, with rows of great trees topping the distant

hills and the peaceful cultivated country between. A country cart

track wanders down past it. As the service was proceeding, the

rough wooden coffin clearly covering the frame of a splendid man

(for it was bigger even than most soldiers coffins) lying there under

the union Jack - the sun shining on the wheatfields and three aeroplanes

wheeling through the sky in the distance near the aerodrome,

two French farming people came by: a middleaged woman in a blue

holland dress carrying some sort of big pewter can on her arm, and

a man, over the middle age, with his scythe fresh from the mowing.

The man took off his cap and leaned on his scythe, and the woman

stood there in the road while the chaplain read. Then I saw her

going away dabbing her eyes, and the man went too, to his work.

It is only a small cemetery at present. There is a cross marking xxx

each grave. They have to be wooden crosses. We are seeing if we can

get a specially strong one put up, with a simple inscription in xxxx

brass. After the war they will no doubt allow more permanent grave

stones to be erected.

I was taking all Leos things, except a few that

[*D12

Page 132*]

35

(8)

Angus preferred to keep, to Aunt Katie next week or the week after

I went and got all his things at once from his battalion and took

them up to Angus. Angus I know was going to send the few notes which

were in Leos pocket book, to Major Rafferty to give to the stretcher

bearers and Corporal Yanner, and to Tilley (the colonels batman) and

any others.)

[*B19

Page 15*]

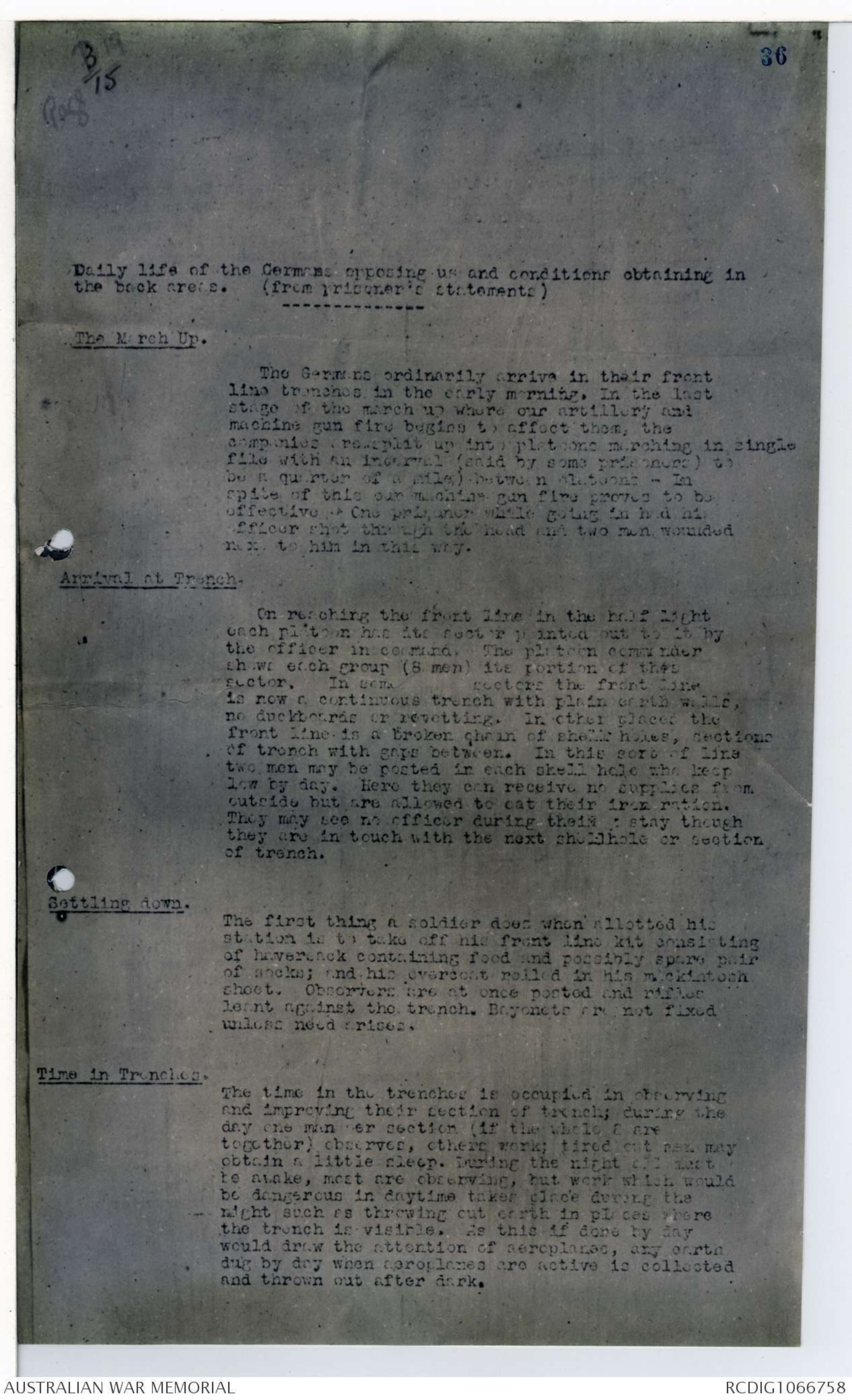

36

Daily life of the Germans opposing us and conditions obtaining in

the back areas. (from prisoner's statements)

The March Up.

The Germans ordinarily arrive in their front

line trenches in the early morning. In the last

stage of the march up where our artillery and

machine gun fire begins to affect them, the

companies re-split up into platoons marching in single

file with an interval (said by some prisoners) to

be a quarter of a mile) between platoons - In

spite of this our machine gun fire proves to be

effective. One prisoner while going in had his

officer shot through the head and two men wounded

next to him in this way.

Arrival at Trench.

On reaching the front line in the half light

each platoon has its sector pointed out to it by

the officer in command. The platoon commander

shows each group (8 men) its portion of this

sector. In some sectors the front line

is now a continuous trench with plain earth walls,

no duckboards or revetting. In other places the

front line is a broken chain of shell holes, Sections

of trench with gaps between. In this sort of line

two men may be posted in each shell hole who keep

low by day. Here they can receive no supplies from

outside but are allowed to eat their iron ration.

They may see no officer during their stay though

they are in touch with the next shellhole or section

of trench.

Settling down.

The first thing a soldier does when allotted his

station is to take off his front line kit consisting

of haversack containing food and possibly spare pair

of socks; and his overcoat rolled in his mackintosh

sheet. Observers are at once posted and rifles

leant against the trench. Bayonets are not fixed

unless need arises.

Time in Trenches.

The time in trenches is occupied in observing

and improving their section of trench; during the

day one man per section (if the whole 8 are

together) observes, others work; tired out men may

obtain a little sleep. During the night all must

be awake, most are observing, but work which would

be dangerous in daytime takes place during the

night such as throwing out earth in places where

the trench is visible. As this if done by day

would draw the attention of aeroplanes, any earth

dug by day when aeroplanes are active is collected

and thrown out after dark.

B19

Page 15

37

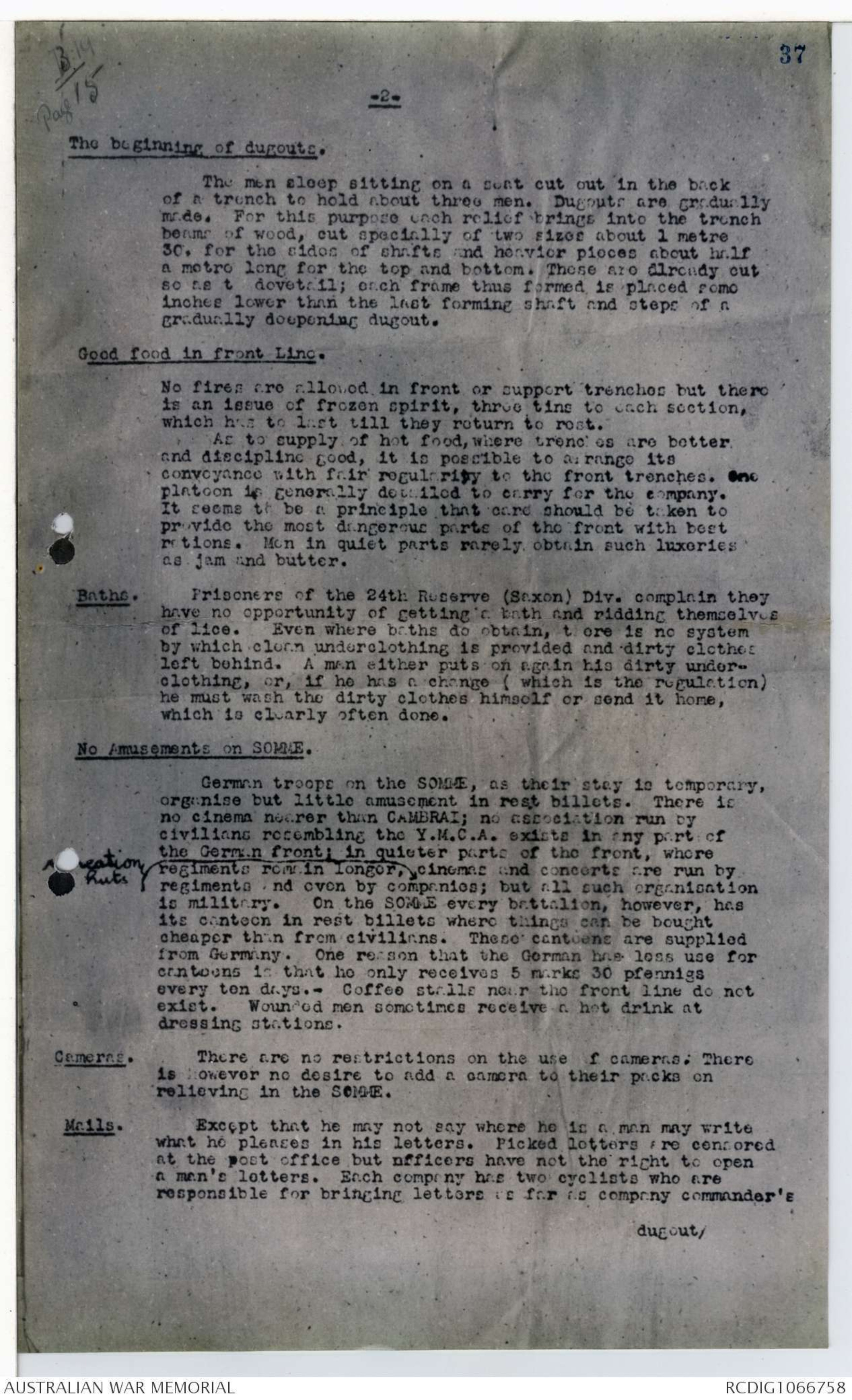

-2-

The beginning of dugouts.

The men sleep sitting on a seat cut out in the back

of a trench to hold about three men. Dugouts are gradually

made. For this purpose each relief brings into the trench

beams of wood, cut specially of two sizes about 1 metre

30. for the sides of shafts and heavier pieces about half

a metre long for the top and bottom. Those are already cut

so as to dovetail; each frame thus formed is placed some

inches lower than the last forming shaft and steps of a

gradually deepening dugout.

Good food in front Line.

No fires are allowed in front or support trenches but there

is an issue of frozen spirit, three tins to each section,

which has to last till they return to rost.

As to supply of hot food, where trenches are better.

and discipline good, it is possible to arrange its

conveyance with fair regularity to the front trenches. One

platoon is generally detailed to carry for the company.

It seems to be a principle that care should be taken to

provide the most dangerous parts of the front with best

rations. Men in quiet parts rarely obtain such luxuries

as jam and butter.

Baths. Prisoners of the 24th Reserve (Saxon) Div. complain they

have no opportunity of getting a bath and ridding themselves

of lice. Even where baths do obtain, there is no system

by which clean underclothing is provided and dirty clothes

left behind. A man either puts on again his dirty underclothing,

or, if he has a change (which is the regulation)

he must wash the dirty clothes himself or send it home,

which is clearly often done.

No Amusements on SOMME.

German troops on the SOMME, as their stay is temporary,

organise but little amusement in rest billets. There is

no cinema nearer than CAMBRAI; no association run by

civilians resembling the Y.M.C.A. exists in any part of

the German front; in quieter parts of the front, where

regiments remain longer,^ [*recreation huts*] cinemas and concerts are run by

regiments and even by companies; but all such organisation

is military. On the SOMME every battalion, however, has

its canteen in rest billets where things can be bought

cheaper than from civilians. These canteens are supplied

from Germany. One reason that the German has less use for

canteens is that he only receives 5 marks 30 pfennigs

every ten days.- Coffee stalls near the front line do not

exist. Wounded men sometimes receive a hot drink at

dressing stations.

Cameras. There are no restrictions on the use of cameras: There

is however no desire to add a camera to their packs on

relieving in the SOMME.

Mails. Except that he may not say where he is a man may write

what he pleases in his letters. Picked letters are censored

at the post office but officers have not the right to open

a man's letters. Each company has two cyclists who are

responsible for bringing letters as far as company commander's

dugout/

Deb Parkinson

Deb ParkinsonThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.