Charles E W Bean, Diaries, AWM38 3DRL 606/117/1 - September - December 1918 - Part 1

AWM38

Official History,

1914-18 War: Records of C E W Bean,

Official Historian.

Diaries and Notebooks

Item number: 3DRL606/117/1

Title: Diary, September - December 1918

Covers fighting of September - October 1918,

breaking up of battalions, W M Hughes in

England and France, the armistice and Bean in

England.

AWM38-3DRL606/117/1

T.D

AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL

ACCESS STATUS

OPEN

No 1 Copy SetNo 2 Copy

Diary No. 117.

Sept 27 1918. to Nov 12 29 1918 Dec. 3, 1918.

1st SET DIARY. No 117.

AWM38 3DRL 606 ITEM 117 [1]

DIARIES AND NOTES OF C. E. W. BEAN

CONCERNING THE WAR OF 1914-1918

THE use of these diaries and notes is subject to conditions laid down in the terms

of gift to the Australian War Memorial. But, apart from those terms, I wish the

following circumstances and considerations to be brought to the notice of every

reader and writer who may use them.

These writings represent only what at the moment of making them I believed to be

true. The diaries were jotted down almost daily with the object of recording what

was then in the writer's mind. Often he wrote them when very tired and half asleep;

also, not infrequently, what he believed to be true was not so – but it does not

follow that he always discovered this, or remembered to correct the mistakes when

discovered. Indeed, he could not always remember that he had written them.

These records should, therefore, be used with great caution, as relating only what

their author, at the time of writing, believed. Further, he cannot, of course, vouch

for the accuracy of statements made to him by others and here recorded. But he

did try to ensure such accuracy by consulting, as far as possible, those who had

seen or otherwise taken part in the events. The constant falsity of second-hand

evidence (on which a large proportion of war stories are founded) was impressed

upon him by the second or third day of the Gallipoli campaign, notwithstanding that those who passed on such stories usually themselves believed them to be true. All second-hand evidence herein should be read with this in mind.

16 Sept. 1946. C. E. W. BEAN.

AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL

ACCESS STATUS

OPEN

2nd Copy.

Diary

Sept. 27 1918

to Nov 16 29 1918.

1

SEPTEMBER 27th. continued. 117

We spent last night in Boulogne and I came on tonight today

to BARLEUX, where Murdoch and Gilmour had already arrived.

a couple of days since. One of the first bits of news

Murdoch told me was that there had been a regular

epidemic of mutinies in the A.I.F. during the last few

days. It was, I believe, the question of the disbandment

of battalions, and arose first out of the case of

the 37th battn., where STOREYm, the Colonel, some time ago

made an unexpected disturbance over the proposed

dissolving of his battalion.

It is a long yarn. Storey was second in command at

Messines, and there, in the confused recriminations which

followed the putting down of a barrage on the 37th and

its withdrawal from the objective, McNICHOLL and Storey

came to loggerheads. Murdoch says the two had been old

enemies in Australia, both being in the Education Dept.

and having some quarrel over their military work.

Whether this is so or not, there is no doubt they were

pretty bitterly opposed after Messines. SMITH, the

colonel of the battalion, who took Storey's xx side, had

to go. McNicholl was supported by MONASH, whose pride

was very much hurt by the fact that the left flank of his

division had not kept in its place with the right flank

when the 4th Div. retired. Lately Storey has been given

the command of his battalion, and no doubt Storey thought

that it was the enmity of McNicholl that caused the 37th

to be picked out as the proper st battalion to be broken

up. Storey first protested to McNicholl and afterwards

wrote a couple of very wild letters to Gen. BIRDWOOD,

over the head of his superior officers. He also made

his opinion quite widely known to the battn., and I fancy

said something to them on parade about the pity of their

being broken up. Monash was very incensed xxxxxxxx

Sto rey's action - which indeed was impossible for any

commanding officer to put up with and disloyal to the

interests of the A.I.F. as a whole - and Monash had

decided to send Storey to England when the news came that

the 37th had refused to be disbanded, and that the men,

when ordered to march off to their new units, had stood

fast. This happened a few days ago.

It so happense that the War Council has been urging

Birdwood to have the breaking up of the battalions carried

out at once in order to keep up the strength of the

divisions. Monash certainly did not want this, but if

the divisions were to be kept up to full strength,

something had to be done. Birdwood came down a few days

ago and informed Monash that the disbandment of the units

which were to be split up must take place. Accordingly

a number of battalions which had been chosen as the ones

to be disbanded were ordered to march their men off to

other units of their brigade. The 54th, 60th, 42nd, 21st,

37th and, I think, the 27th or 26th, were amongst these.

I am certain of all but the 26th or 27th.

When the 37th struck the others did the same; the

54th and 21st seemed to have been especially firm. Their

officers and N.C.O.'s in each case, when the order came to

the battalion on parade to join its new unit, left the

battalion and went to their new homes; but the men of the

battalion stood fast. The discipline of the battalions

was rigorously kept up. The new officers and N.C.O.'s

did not assume stars or stripes, but took charge of the

battalion on parade, N.C.O.'s told off their platoons

and handed them over to the platoon commander, who reported

to the Company commander. The "Colonel" roared his men up

in approved

3

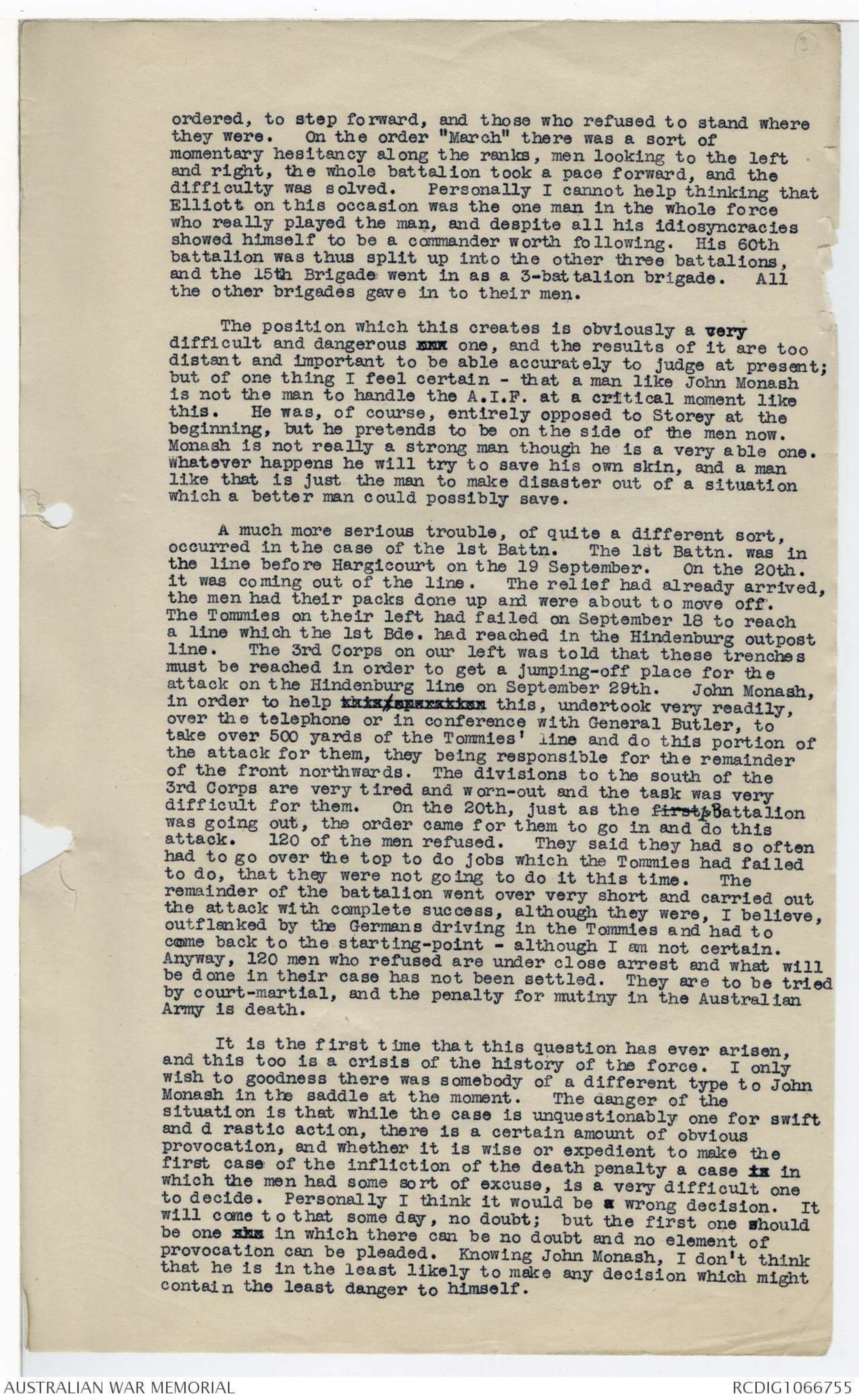

ordered, to step forward, and those who refused to stand where

they were. On the order "March" there was a sort of

momentary hesitancy along the ranks, men looking to the left

and right, the whole battalion took a pace forward, and the

difficulty was solved. Personally I cannot help thinking that

Elliott on this occasion was the one man in the whole force

who really played the man, and despite all his idiosyncracies

showed himself to be a commander worth following. His 60th

battalion was thus split up into the other three battalions,

and the 15th Brigade went in as a 3-battalion brigade. All

the other brigades gave in to their men.

The position which this creates is obviously a very

difficult and dangerous xxx one, and the results of it are too

distant and important to be able accurately to judge at present;

but of one thing I feel certain - that a man like John Monash

is not the man to handle the A.I.F. at a critical moment like

this. He was, of course, entirely opposed to Storey at the

beginning, but he pretends to be on the side of the men now.

Monash is not really a strong man though he is a very able one.

Whatever happens he will try to save his own skin, and a man

like that is just the man to make disaster out of a situation

which a better man could possibly save.

A much more serious trouble, of quite a different sort,

occurred in the case of the 1st Battn. The 1st Battn. was in

the line before Hargicourt on the 19 September. On the 20th.

it was coming out of the line. The relief had already arrived,

the men had their packs done up and were about to move off.

The Tommies on their left had failed on September 18 to reach

a line which the 1st Bde. had reached in the Hindenburg outpost

line. The 3rd Corps on our left was told that these trenches

must be reached in order to get a jumping-off place for the

attack on the Hindenburg line on September 29th. John Monash,

in order to help xxxxxxxxxxxx this, undertook very readily,

over the telephone or in conference with General Butler, to

take over 500 yards of the Tommies' line and do this portion of

the attack for them, they being responsible for the remainder

of the front northwards. The divisions to the south of the

3rd Corps are very tired and worn-out and the task was very

difficult for them. On the 20th, just as the first 1st Battalion

was going out, the order came for them to go in and do this

attack. 120 of the men refused. They said they had so often

had to go over the top to do jobs which the Tommies had failed

to do, that they were not going to do it this time. The

remainder of the battalion went over very short and carried out

the attack with complete success, although they were, I believe,

outflanked by the Germans driving in the Tommies and had to

come back to the starting-point - although I am not certain.

Anyway, 120 men who refused are under close arrest and what will

be done in their case has not been settled. They are to be tried

by court-martial, and the penalty for mutiny in the Australian

Army is death.

It is the first time that this question has ever arisen,

and this too is a crisis of the history of the force. I only

wish to goodness there was somebody of a different type to John

Monash in the saddle at the moment. The danger of the

situation is that while the case is unquestionably one for swift

and d rastic action, there is a certain amount of obvious

provocation, and whether it is wise or expedient to make the

first case of the infliction of the death penalty a case is in

which the men had some sort of excuse, is a very difficult one

to decide. Personally I think it would be a wrong decision. It

will come t o that some day, no doubt; but the first one should

be one xxx in which there can be no doubt and no element of

provocation can be pleaded. Knowing John Monash, I don't think

that he is in the least likely to make any decision which might

contain the least danger to himself.

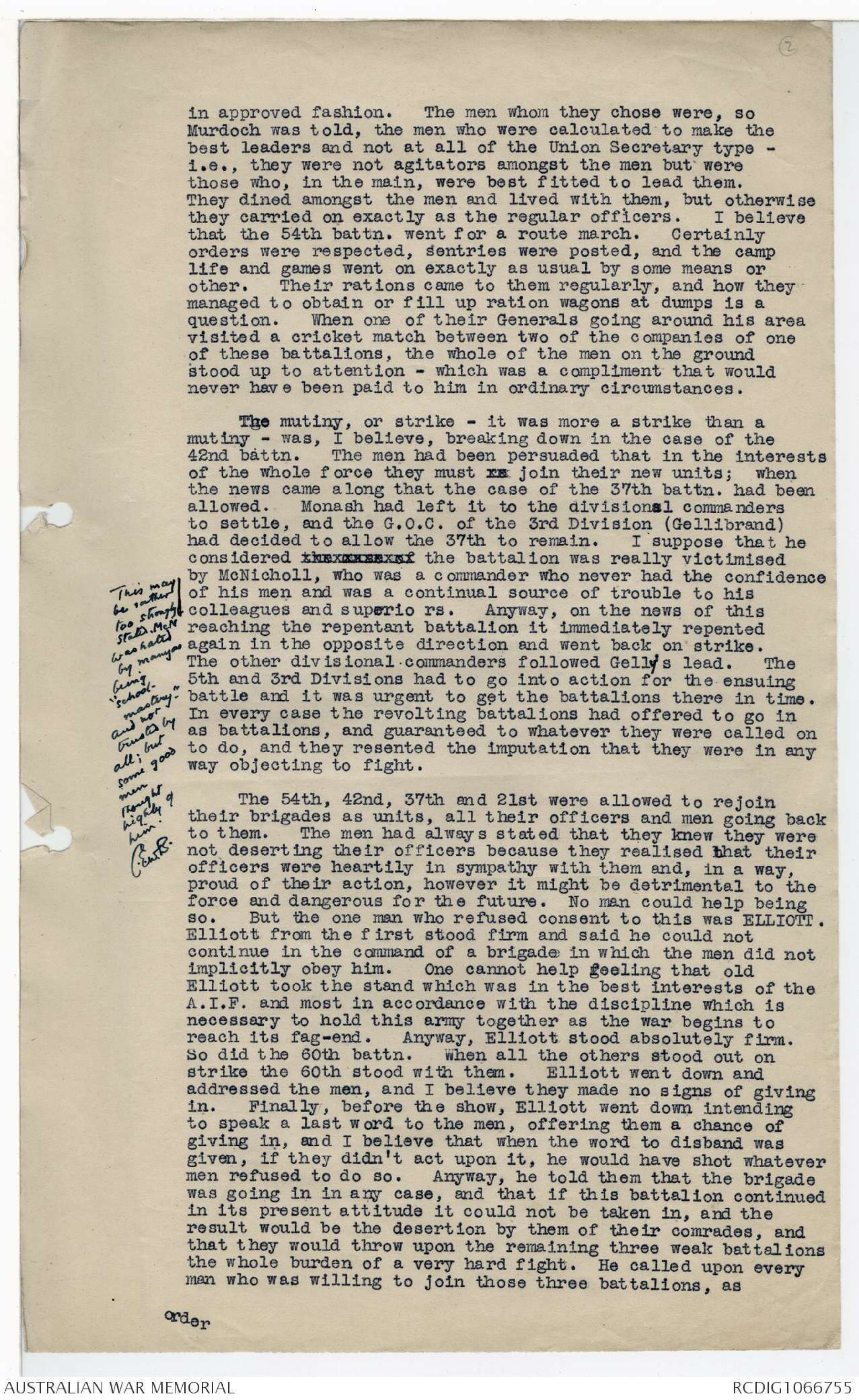

2

in approved fashion. The men whom they chose were, so

Murdoch was told, the men who were calculated to make the

best leaders and not at all of the Union Secretary type -

i.e., they were not agitators amongst the men but were

those who, in the main, were best fitted to lead them.

They dined amongst the men and lived with them, but otherwise

they carried on exactly as the regular officers. I believe

that the 54th battn. went for a route march. Certainly

orders were respected, sentries were posted, and the camp

life and games went on exactly as usual by some means or

other. Their rations came to them regularly, and how they

managed to obtain or fill up ration wagons at dumps is a

question. When one of their Generals going around his area

visited a cricket match between two of the companies of one

of these battalions, the whole of the men on the ground

stood up to attention - which was a compliment that would

never have been paid to him in ordinary circumstances.

The mutiny, or strike - it was more a strike than a

mutiny - was, I believe, breaking down in the case of the

42nd battn. The men had been persuaded that in the interests

of the whole force they must xx join their new units; when

the news came along that the case of the 37th battn. had been

allowed. Monash had left it to the divisional commanders

to settle, and the G.O.C. of the 3rd Division (Gellibrand)

had decided to allow the 37th to remain. I suppose that he

considered xxxxxxxxxx the battalion was really victimised

by McNicholl, who was a commander who never had the confidence

of his men and was a continual source of trouble to his

colleagues and superi ors. Anyway, on the news of this

[*This may be rather too strongly stated. McN was hated by many as being "school-mastery", and not trusted by all; but some good men thought highly of him. C. E. W. B.*]

reaching the repentant battalion it immediately repented

again in the opposite direction and went back on strike.

The other divisional commanders followed Gelly's lead. The

5th and 3rd Divisions had to go into action for the ensuing

battle and it was urgent to get the battalions there in time.

In every case the revolting battalions had offered to go in

as battalions, and guaranteed to whatever they were called on

to do, and they resented the imputation that they were in any

way objecting to fight.

The 54th, 42nd, 37th and 21st were allowed to rejoin

their brigades as units, all their officers and men going back

to them. The men had always stated that they knew they were

not deserting their officers because they realised that their

officers were heartily in sympathy with them and, in a way,

proud of their action, however it might be detrimental to the

force and dangerous for the future. No man could help being

so. But the one man who refused consent to this was ELLIOTT.

Elliott from the first stood firm and said he could not

continue in the command of a brigade in which the men did not

implicitly obey him. One cannot help feeling that old

Elliott took the stand which was in the best interests of the

A.I.F. and most in accordance with the discipline which is

necessary to hold this army together as the war begins to

reach its fag-end. Anyway, Elliott stood absolutely firm.

So did the 60th battn. When all the others stood out on

strike the 60th stood with them. Elliott went down and

addressed the men, and I believe they made no signs of giving

in. Finally, before the show, Elliott went down intending

to speak a last word to the men, offering them a chance of

giving in, and I believe that when the word to disband was

given, if they didn't act upon it, he would have shot whatever

men refused to do so. Anyway, he told them that the brigade

was going in in any case, and that if this battalion continued

in its present attitude it could not be taken in, and the

result would be the desertion by them of their comrades, and

that they would throw upon the remaining three weak battalions

the whole burden of a very hard fight. He called upon every

man who was willing to join those three battalions, as

order

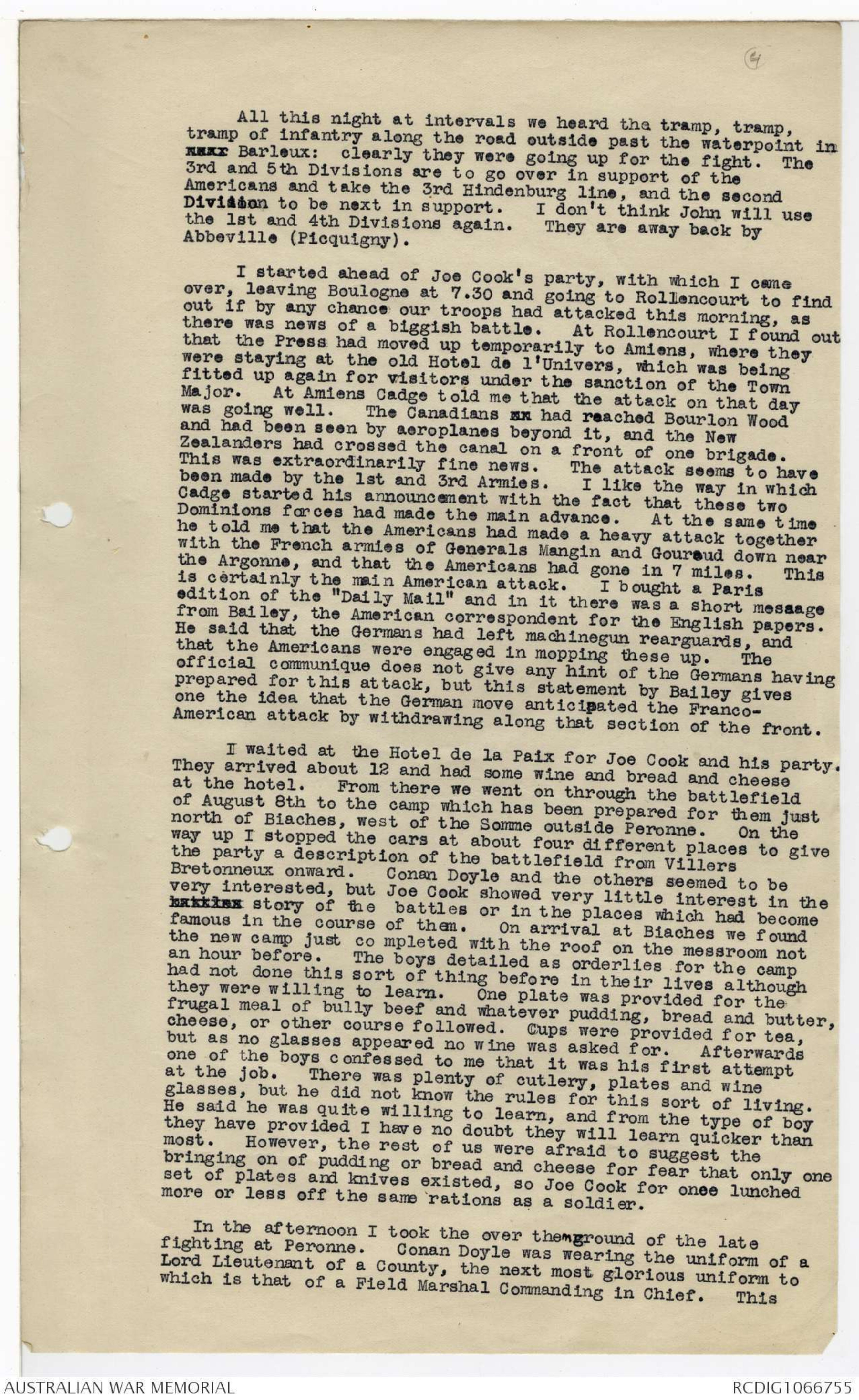

4

All this night at intervals we heard the tramp, tramp,

tramp of infantry along the road outside past the waterpoint in

xxxx Barleux: clearly they were going up for the fight. The

3rd and 5th Divisions are to go over in support of the

Americans and take the 3rd Hindenburg line, and the second

Division to be next in support. I don't think John will use

the 1st and 4th Divisions again. They are away back by

Abbeville (Picquigny).

I started ahead of Joe Cook's party, with which I came

over, leaving Boulogne at 7.30 and going to Rollencourt to find

out if by any chance our troops had attacked this morning, as

there was news of a biggish battle. At Rollencourt I found out

that the Press had moved up temporarily to Amiens, where they

were staying at the old Hotel de l'Univers, which was being

fitted up again for visitors under the sanction of the Town

Major. At Amiens Cadge told me that the attack on that day

was going well. The Canadians xx had reached Bourlon Wood

and had been seen by aeroplanes beyond it, and the New

Zealanders had crossed the canal on a front of one brigade.

This was extraordinarily fine news. The attack seems to have

been made by the 1st and 3rd Armies. I like the way in which

Cadge started his announcement with the fact that these two

Dominions forces had made the main advance. At the same time

he told me that the Americans had made a heavy attack together

with the French armies of Generals Mangin and Gouroud down near

the Argonne, and that the Americans had gone in 7 miles. This

is certainly the main American attack. I bought a Paris

edition of the "Daily Mail" and in it there was a short message

from Bailey, the American correspondent for the English papers.

He said that the Germans had left machinegun rearguards, and

that the Americans were engaged in mopping these up. The

official communique does not give any hint of the Germans having

prepared for this attack, but this statement by Bailey gives

one the idea that the German move anticipated the Franco-

American attack by withdrawing along that section of the front.

I waited at the Hotel de la Paix for Joe Cook and his party.

They arrived about 12 and had some wine and bread and cheese

at the hotel. From there we went on through the battlefield

of August 8th to the camp which has been prepared for them just

north of Biaches, west of the Somme outside Peronne. On the

way up I stopped the cars at about four different places to give

the party a description of the battlefield from Villers

Bretonneux onward. Conan Doyle and the others seemed to be

very interested, but Joe Cook showed very little interest in the

xxxxxxx story of the battles or in the places which had become

famous in the course of then. On arrival at Biaches we found

the new camp just co mpleted with the roof on the messroom not

an hour before. The boys detailed as orderlies for the camp

had not done this sort of thing before in their lives although

they were willing to learn. One plate was provided for the

frugal meal of bully beef and whatever pudding, bread and butter,

cheese, or other course followed. Cups were provided for tea,

but as no glasses appeared no wine was asked for. Afterwards

one of the boys c onfessed to me that it was his first attempt

at the job. There was plenty of cutlery, plates and wine

glasses, but he did not know the rules for this sort of living.

He said he was quite willing to learn, and from the type of boy

they have provided I have no doubt they will learn quicker than

most. However, the rest of us were afraid to suggest the

bringing on of pudding or bread and cheese for fear that only one

set of plates and knives existed, so Joe Cook for once lunched

more or less off the same rations as a soldier.

In the afternoon I took the over the ground of the late

fighting at Peronne. Conan Doyle was wearing the uniform of a

Lord Lieutenant of a County, the next most glorious uniform to

which is that of a Field Marshal Commanding in Chief. This

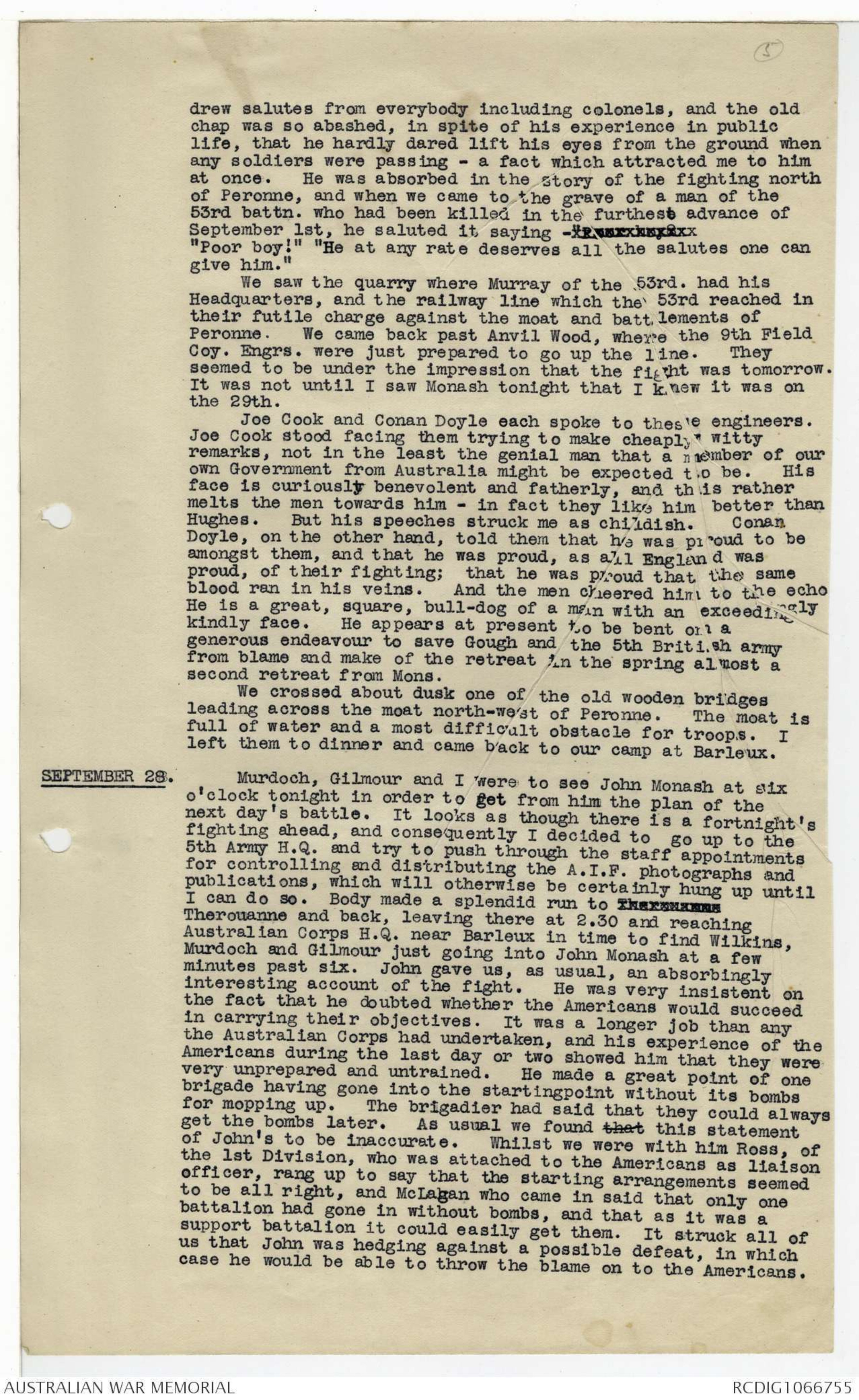

5

drew salutes from everybody including colonels, and the old

chap was so abashed, in spite of his experience in public

life, that he hardly dared lift his eyes from the ground when

any soldiers were passing - a fact which attracted me to him

at once. He was absorbed in the story of the fighting north

of Peronne, and when we came to the grave of a man of the

53rd battn, who had been killed in the furthest advance of

September 1st, he saluted it saying -xxxxxxxxxx

"Poor boy!" "He at any rate deserves all the salutes one can

give him."

We saw the quarry where Murray of the 53rd. had his

Headquarters, and the railway line which the 53rd reached in

their futile charge against the moat and battlements of

Peronne. We came back past Anvil Wood, where the 9th Field

Coy. Engrs. were just prepared to go up the line. They

seemed to be under the impression that the fight was tomorrow.

It was not until I saw Monash tonight that I knew it was on

the 29th.

Joe Cook and Conan Doyle each spoke to these engineers.

Joe Cook stood facing them trying to make cheaply witty

remarks, not in the least the genial man that a number of our

own Government from Australia might be expected to be. His

face is curiously benevolent and fatherly, and this rather

melts the men towards him - in fact they like him better than

Hughes. But his speeches struck me as childish. Conan

Doyle, on the other hand, told them that he was proud to be

amongst them, and that he was proud, as all England was

proud, of their fighting; that he was proud that the same

blood ran in his veins. And the men cheered him to the echo.

He is a great, square, bull-dog of a man with an exceedingly

kindly face. He appears at present to be bent on a

generous endeavour to save Gough and the 5th British army

from blame and make of the retreat in the spring almost a

second retreat from Mons.

We crossed about dusk one of the old wooden bridges

leading across the moat north-west of Peronne. The moat is

full of water and a most difficult obstacle for troops. I

left them to dinner and came back to our camp at Barleux.

SEPTEMBER 28. Murdoch, Gilmour and I were to see John Monash at six

o'clock tonight in order to get from him the plan of the

next day's battle. It looks as though there is a fortnight's

fighting ahead, and consequently I decided to go up to the

5th Army H.Q. and try to push through the staff appointments

for controlling and distributing the A.I.F. photographs and

publications, which will otherwise be certainly hung up until

I can do so. Body made a splendid run to xxxxxxxx

Therouanne and back, leaving there at 2.30 and reaching

Australian Corps H.Q. near Barleux in time to find Wilkins,

Murdoch and Gilmour just going into John Monash at a few

minutes past six. John gave us, as usual, an absorbingly

interesting account of the fight. He was very insistent on

the fact that he doubted whether the Americans would succeed

in carrying their objectives. It was a longer job than any

the Australian Corps had undertaken, and his experience of the

Americans during the last day or two showed him that they were

very unprepared and untrained. He made a great point of one

brigade having gone into the startingpoint without its bombs

for mopping up. The brigadier had said that they could always

get the bombs later. As usual we found that this statement

of John's to be inaccurate. Whilst we were with him Ross, of

the 1st Division, who was attached to the Americans as liaison

officer, rang up to say that the starting arrangements seemed

to be all right, and McLagan who came in said that only one

battalion had gone in without bombs, and that as it was a

support battalion it could easily get them. It struck all of

us that John was hedging against a possible defeat, in which

case he would be able to throw the blame on to the Americans.

6

The Australian troops will not go over until 11 7o'clock

tomorrow, leaving their starting point and reaching the

American objective, where they will pass through the American

troops, at 11 o'clock. This gives four clear hours for

roadmaking. We shall go up to the battlefield in time to

see the Australians go over. The Meteor says that the weather

is going to be fine.

Joe Cook has been chafing like an impatient child to-day.

He knew that Hughes when he was over here addressed the troops

several times, and I had told him that the men had received

Hughes particularly well on several occasions. Joe evidently

wanted to do the same: "Conan Doyle here wants to see

battlefields, but I want to see the men", he said. "They told

me I could see men and I have not seen men. What I want to

know is when I can see some of the men."

Plunkett, a genial old farmer, who is a captain in the 3rd.

Battn. and is acting as one of the conducting officers, arranged

with great trouble to take Cook off to Abbeville and Picquigny

to see the 1st and 4th Divisions in the back area. Joe went

off with him in an aggressive frame of mind, and as they

went through xxxxx Longueau the car completelybroke down.

Being a war-time car it had inferior metal in the engines

and something snapped. Plunkett, by using all his sense and

push, managed to get the loan of a small runabout car to take

Cook on into Amiens, and there tried to persuade him

to have lunch while he himself hurried around to raise another motor

car. Cook said he didn't want to have lunch - he wanted to

see the troops. As the troops were 20 miles away and there

was no means of getting there except by finding a motorcar,

which Plunkett was trying to do, this was not very helpful.

Eventually Plunkett raised a car from the 1st Division,

and they arrived there to find that Cook's son, whom Cook

wanted specially to visit, was away back acting as liaison

officer with the Americans who were attacking next day. The

result of this was that Cook began worrying about his son.

"I know old Cook of the 2nd. Battn., and I knew damned well

there was nothing to worry about - he'd never hop over the

top with the Americans", said Plunkett; but it took a long

time to convince Joe Cook that his s on was not going into

immediate and sudden death. However, by the time they had

arrived back at the camp he had managed to allay Cook's fears

on this point. As they, came in the first thing that young

Lowden, the other conducting officer, said was - "Well, Mr.

Cook, I hear your boy is going over the top with the

Americans tomorrow. It was just after this that Murdoch,

Wilkins, Dyson and myself walked in to their messroom, We

noticed that the table didn't appear to be a cheerful one -

in fact nobody seemed to be speaking. Cook disappeared to

bed at once and Lowden and Plunkett each took me out and

explained for 10 minutes that if Billy Hughes was a handful

Joe Cook was a "Bastard, and a damned sight worse!"

SEPTEMBER 29th. For the first time in the last 12 months we have come

back from a battle that went wrong. The last one was

on October 12th at Paschendaale, and this went almost as wrong as

that. We started late this morning. We were going up to see

the Australian infantry start at 9 near Gillement farm 2 miles

east of Ronssoy. Gillement Farm was the farthest point that

Wilkins had reconnoitred, and we calculated that from there

we should be able to look down the valley towards Le Catelet,

and by crossing over into the next ridge to the east side of

the railway ridge just beyond the line of the canal tunnel,

we ought to be able to see up the line towards Beaurevoir

which our troops would then be attacking. By winding up the

high lands which lie eastward from this point we could, if the

shelling were in any way moderate, keep in touch with the

battle as it advanced.

The party of visitors was in trouble to-day, having only

one car for the whole seven. My car had broken down with a

weak spring- also

7

weak spring - also a result of wartime metal, - and Murdoch's

car was already full. Accordingly it was suggested that Smart

who was interested in seeing how the official photographs were

taken, should go up with Casserley, the Press photographer, and

take one of the party with him. Dyson offered to go with

Wilkins to Gillement Farm where he might wait for us. Murdoch,

Gilmour and myself proposed to go through Ronssoy to a point near

Gillement Farm and work out from there. We mistook our turning

in Templeux and reached Hargicourt by mistake at about 10 a.m.

We turned back and passed through Ronssoy towards Gillement Farm,

leaving the car just beyond the first crossroad past Ronssoy.

The crest of the hill is only a few hundred yards ahead.

On our way up we called in at the 3rd Division, which was

very well advanced between Templeux and Ronssoy. They told us

there that the Americans were said to have reached the green

line - which was their objective - and the 2nd Hindenburg trench

system, but that they had left any number of German machine gun

posts, and that our brigades as they started to go forward after

the Americans had been held up at once by machine gun fire. The

right, so far as was known, had gone a good deal better, and

Bellicourt had been taken; but on the left in front of the 3rd

Division, although Bony had been passed and possibly taken by the

Americans, it was quite unapproachable at present owing to the

German machine guns in it. At 3rd. Div. H.Q. we found Smart

and Berry (the editor of the "Sunday Times") with Casserley,

the Press Photographer. As Casserley was new to it I advised

them all to come along with me. The crest of the hill

was about 300 or 400 yards away. As we walked along the road

towards Gillemont Farm we noticed at least 20 American dead

who must have been killed by shell bursts - possibly in some

cases by machine gun fire - before they had even reached their

starting point. In the hollow on our right were a number of

guns and a line of tanks. On our left on the flat surface of

the hill was a disabled tank and a number of men in shell holes -

largely belonging to the 3rd. Div. M.G. Battn. Men occasionally

crossed the hill-crest on our left front. As occasional shells

burst up the road I thought I thought we would make towards

our front left for the hilltop where from the crest we ought to

be able to get a v iew of what was happening towards the northern

mouth of the t unnel and Bony. We went over, Murdo ch and I in

front and Smart and Bury following, and had not gone 100 yards

when the Germans burst several shells not far away on the left.

I altered the course a little to the right past these, and the

next salvo fell right amongst us - one whizzbang shell burst

about 10 yards behind between Murdoch and myself and about 10 yards

ahead of Smart. I signed to them to get down into shell-holes,

and we sat there while four or five salvoes came over, when the

shelling ceased.

Clearly things were too hot for us to take the party in that

direction. There was also a fairly constant crackle of machine

gun fire in that direction. Accordingly we turned back and walked

towards the valley intending to go around to the right where the

5th Division were and where the attack had succeeded. On

reaching the line of tanks we found that these tanks had each

been blown up by a mine which was placed under the wire. Men

who had seen them told us that the mines had heaved the tanks

slightly and burst their travellers. The men inside were in some

cases killed. Later on Gellibrand told us that these were

American tanks and that the mines which had blown them up were

old British mines which had been planted in the wire before the

German attack on March 21st last year and remained in it still.

There were, he said, two notices of "Danger" and the 3rd Div.

were aware of this and guided their tanks another way or laid

down routes to avoid them. It looked as if the Americans had not

been warned and had been allowed to blunder on to the British

mines by s ome terrible mistake. Anyway a line of eight of them

were there lying along the wire, and we who saw them at first

thought the Germans had successfully solved the problem of dealing

with tanks. How these mines would stand a heavy bombardment I

don't know. They seem to have consisted of the old plumpudding

Sam scott

Sam scottThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.