Charles E W Bean, Diaries, AWM38 3DRL 606/276/1 - 1928-1937 - Part 10

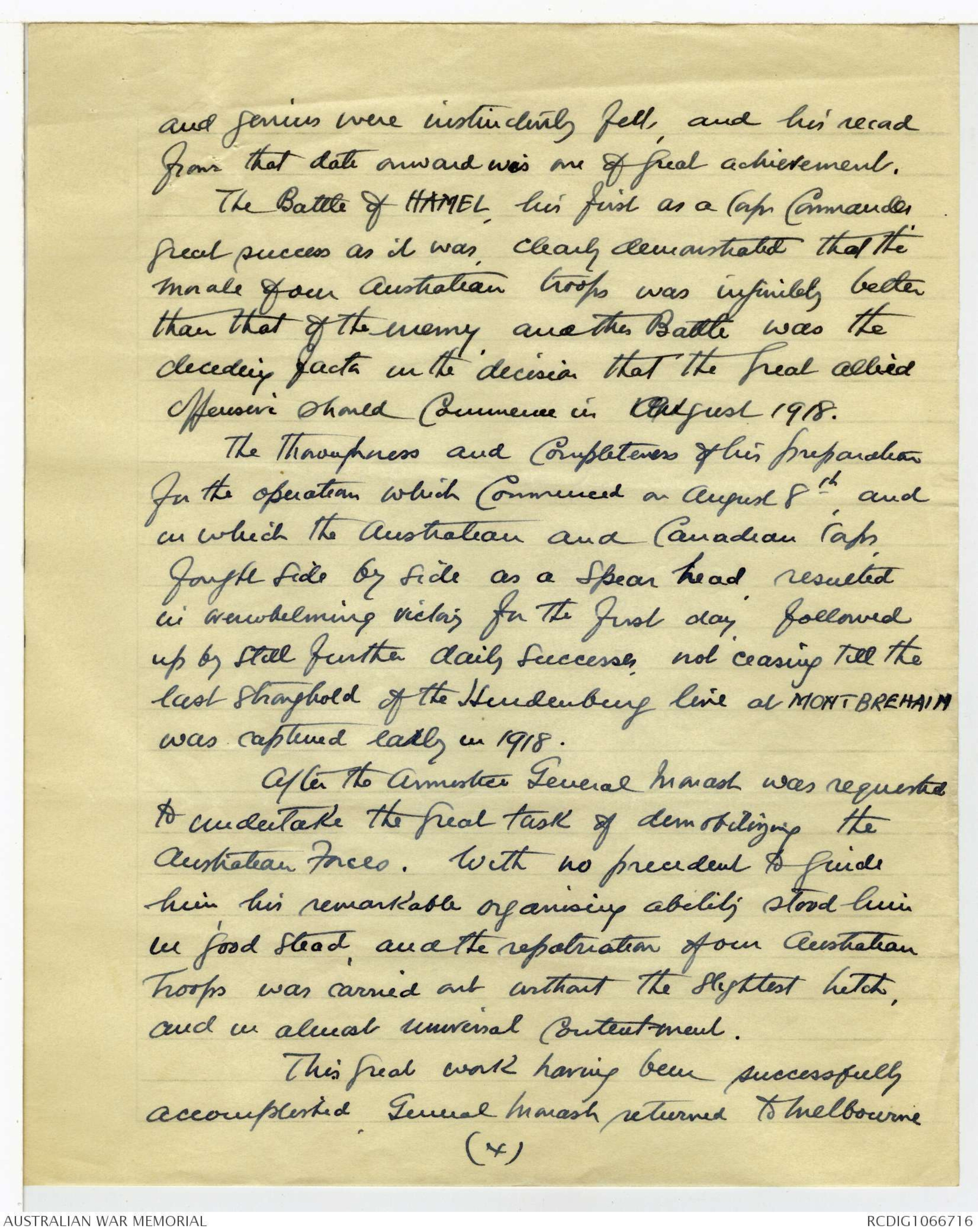

and jerries were instinctively felt, and his record

from that date onward was one of great achievement.

the Battle of HAMEL, his first as a Corps Commander great success as it was, clearly demonstrated that the morale from Australian troops was infinitely better than that of the enemy and this Battle was the deciding fact in the decision that the Great Allied Offensive should commence in August 1918.

The thoroughness and completeness of his preparation for the operation which commenced on August 8th, and in which the Australian and Canadian Corps fought side by side as a spear head resulted in overwhelming victory for the first day followed up by still further daily successes, not ceasing till the last stronghold of the Hindenburg line at MONT BREHAIN was captured early in 1918.

After the Armistice General Monash was requested to undertake the great task of demobilizing the Australian forces. With no precedent to guide him his remarkable organising ability stood him in good stead, and the repatriation of our Australian Troops was carried out without the slightest hitch, and in almost universal contentment.

This great work having been successfully accomplished, General Monash returned to Melbourne

(4)

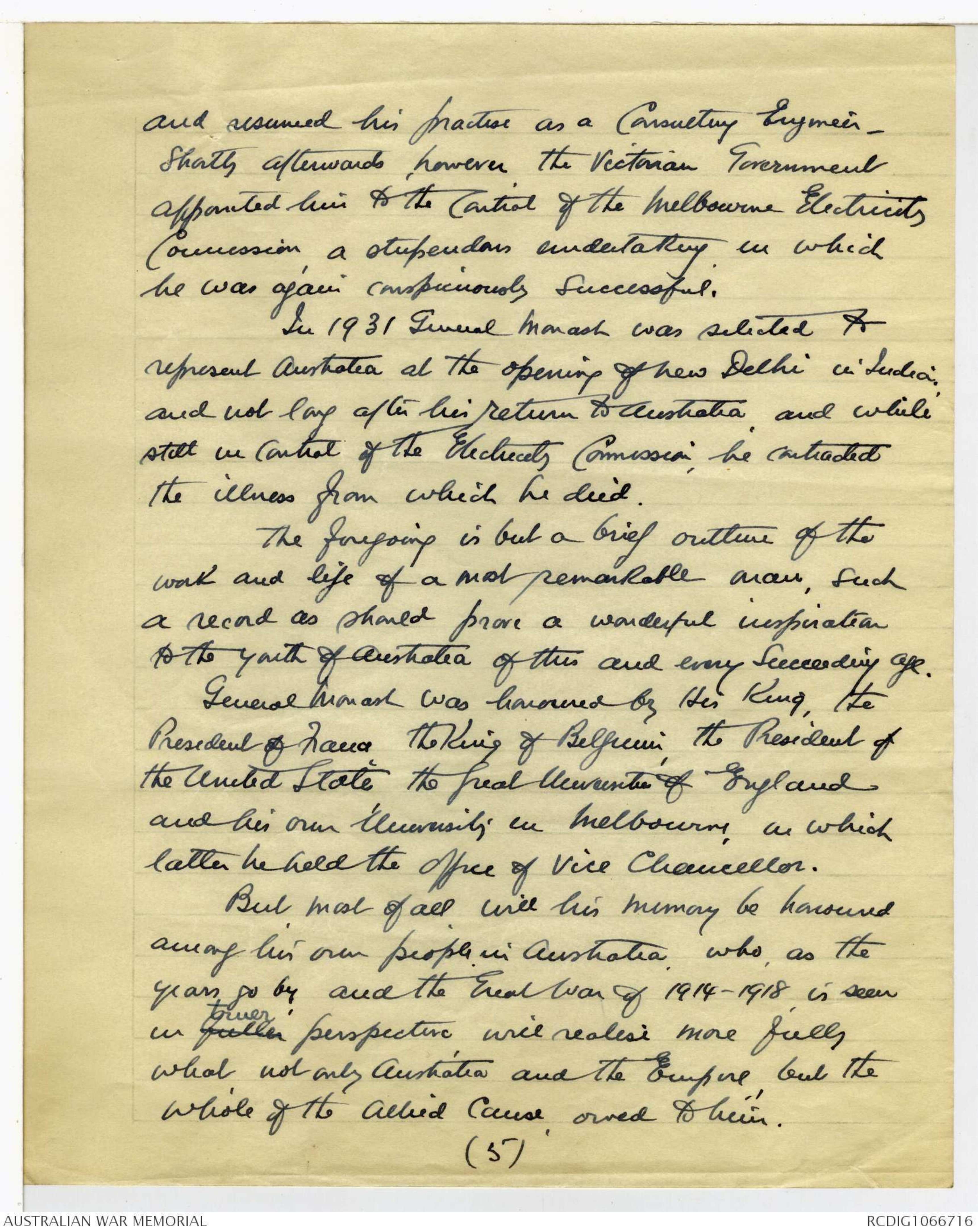

and resumed his practise as a Consulting Engineer. Shortly afterwards however, the Victorian Government appointed him to the control of the Melbourne Electricity Commission, a stupendous undertaking in which he was again conspicuously successful.

In 1931 General Monash was selected to represent Australia at the opening of New Delhi in India and not long after his return to Australia, and while still in control of the Electricity Commission, he contracted the illness from which he died.

The forgoing is but a brief outline of the work and life of a most remarkable man, such a record as should prove a wonderful inspiration to the youth of Austrlia of this and every succeeding age.

General Monash was honoured by the King, the President of France, the King of Belgium, the President of the United States, the great Universities of England and his own University in Melbourne, in which latter he held the office of Vice Chancellor.

But most of all will his memory be honoured among his own people in Australia who, as the years go by, and the Great War of 1914-1918 is seen in truer perspective, will realise more fully what not only Australia and the Empire, but the whole of the Allied Cause, owed to him.

(5)

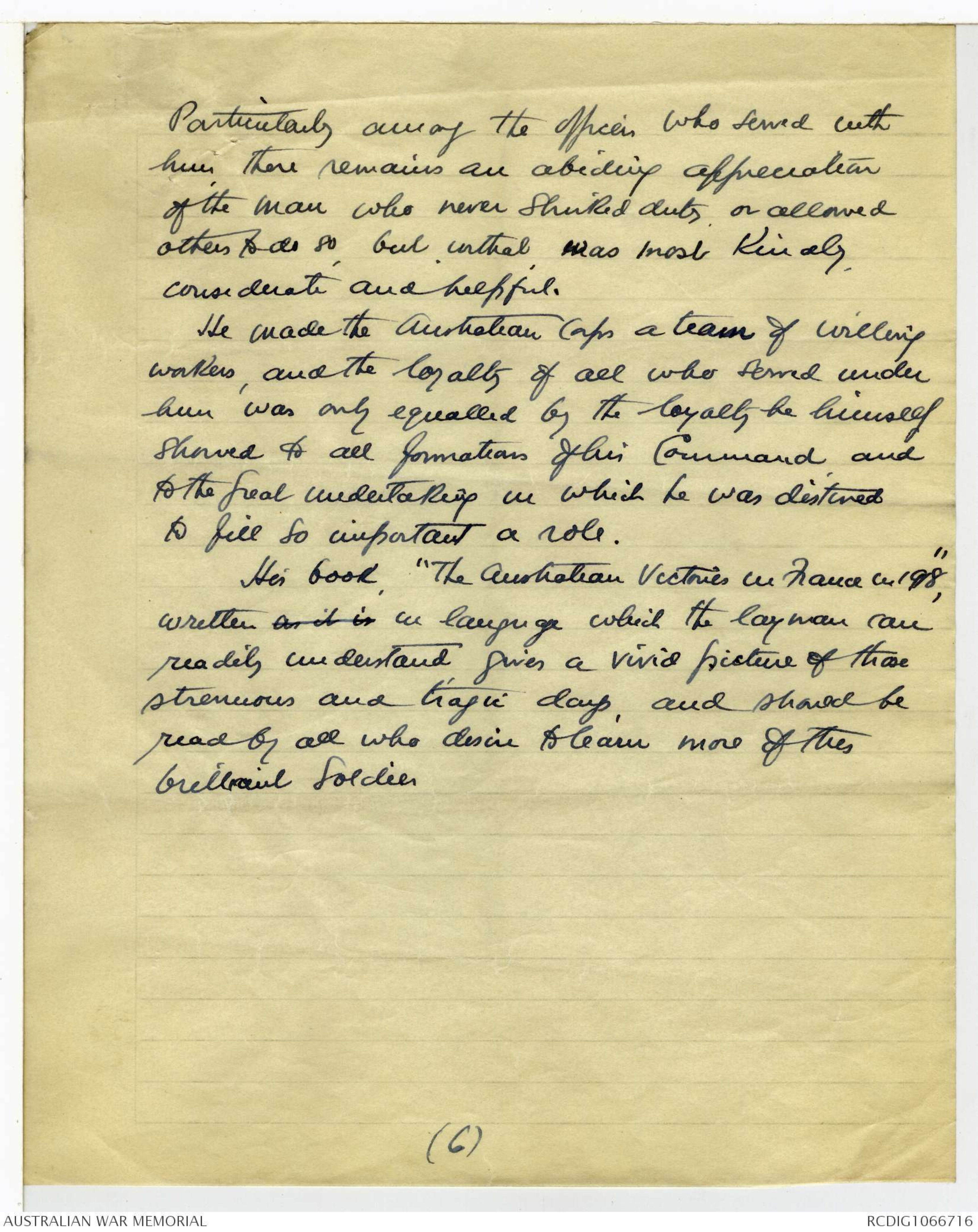

Particularly among the officers who served with him, there remains an abiding appreciation of trhe man who never shirked duty or allowed others to do so, but in that was most kindly, considerate and helpful.

He made the Australian Corps a team of willing workers, and the loyalty of all who served under him was only equalled by the loyalty he himself showed to all formations of his Command and to the great undertakings in which he was destined to fill so important a role.

His book "The Australian Victories in France in 1918" written in language which the layman can readily understand gives a vivid picture of those strenuous and tragic days, and should be read by all who desire to learn more of this brilliant soldier.

(6)

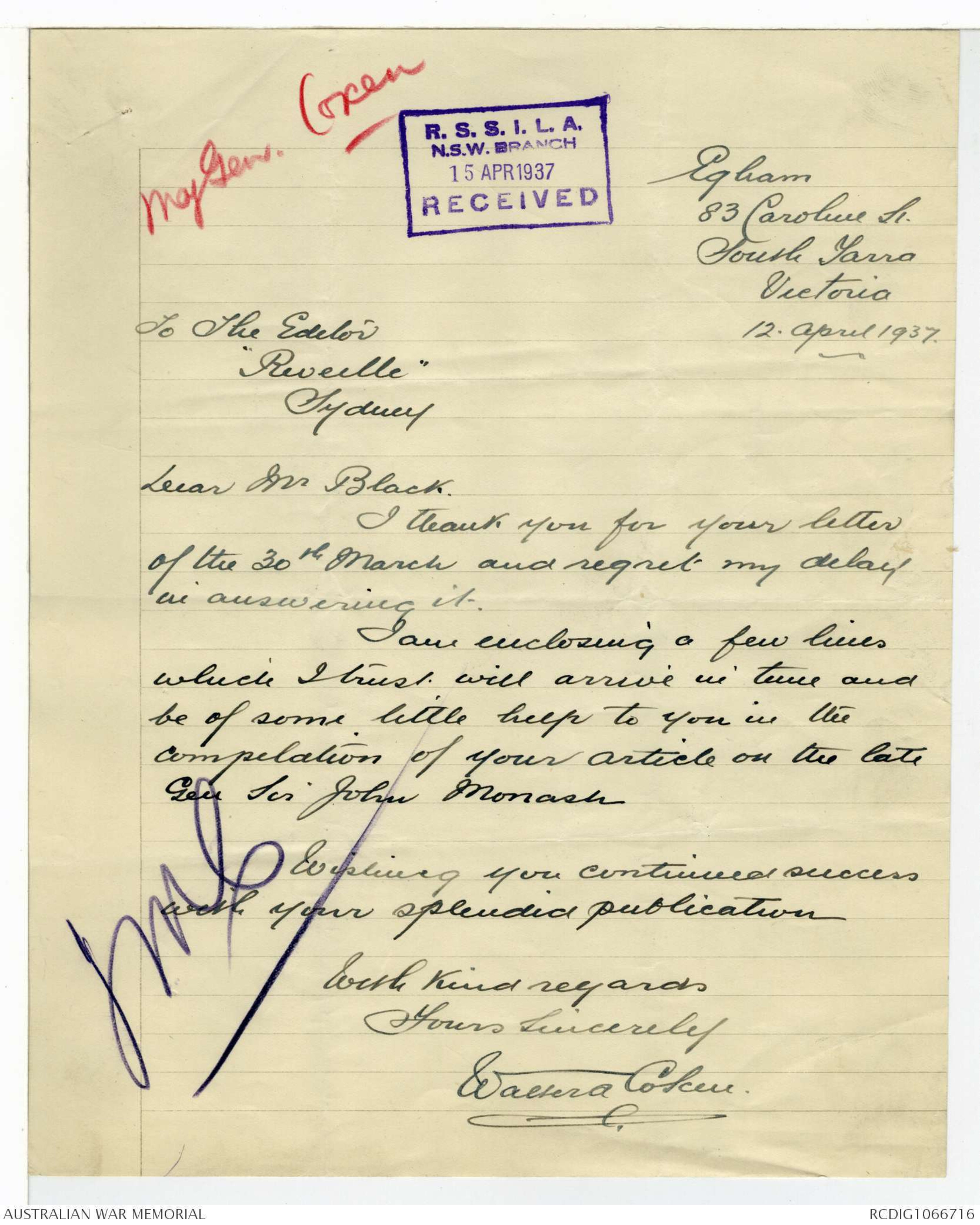

Maj. Gen. Oxen

R.S.S.I.L.A.

NSW Branch

15 Apr 1937

RECEIVED

Egham

83 Caroline St.

South Yarra

Victoria

12 April 1937

To The Editor

"Reveille"

Sydney

Dear Mr Black.

I thank you for your letter of the 30th March and regret my delay in answering it.

I am enclosing a few lines which I trust will arrive in time and be of some little help to you in the compilation of your article on the late Gen. Sir John Monash.

Wishing you continued success with your splendid publication.

With kind regards

Yours sincerely

Walter A Coxen

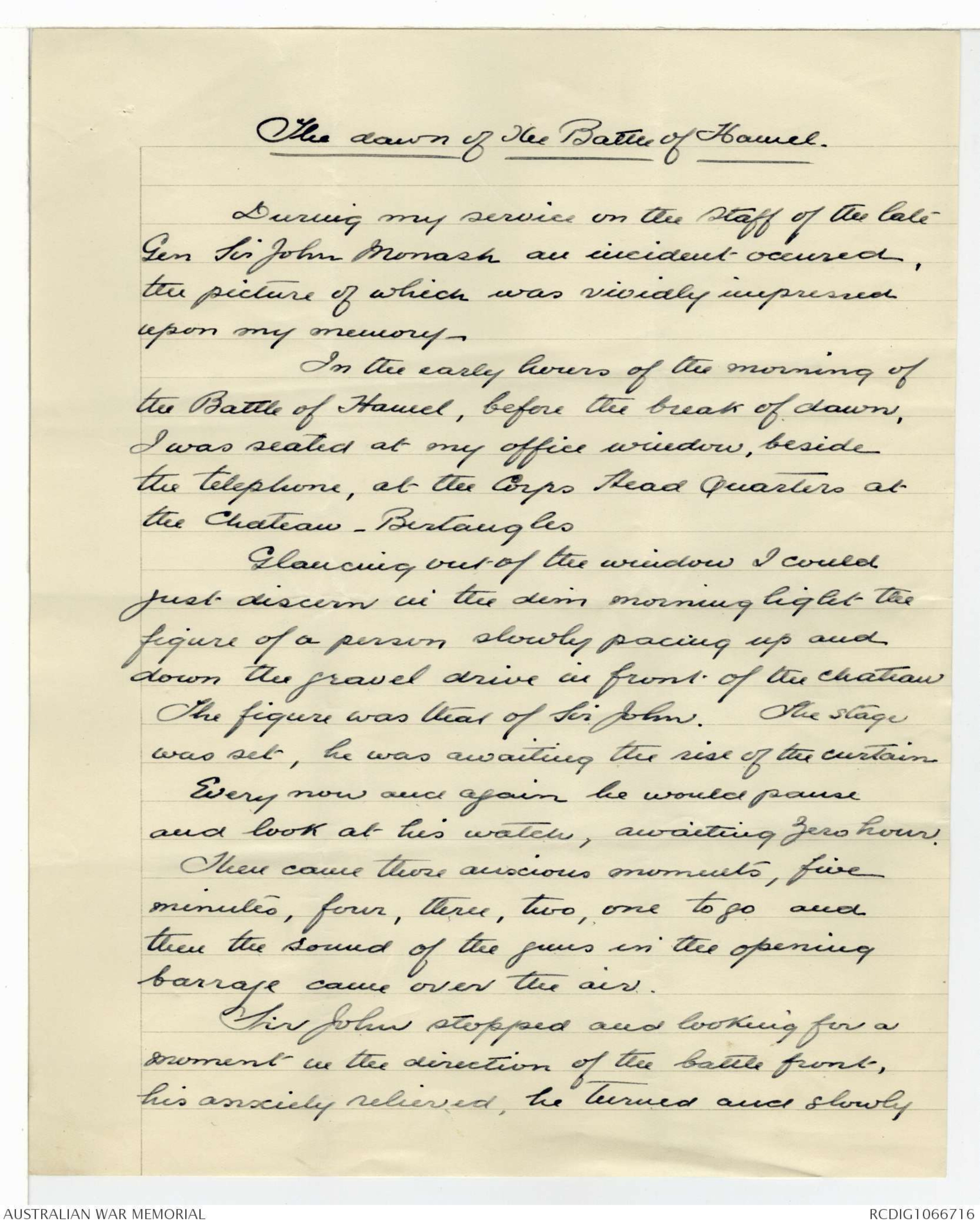

The dawn of the Battle of Hamel

During my service in the staff of the late Gen Sir John Monash an incident occured, the picture of which was vividly impressed upon my memory.

In the early hours of the morning of the Battle of Hamel, before the break of dawn, I was seated at my office window, beside the telephone, at the Corps Head Quarters at the Chateau - Bertangles.

Glancing out of the window I could just discern in the dim morning light the figure of a person slowly pacing up and down the gravel drive in front of the chateau. The figure was that of Sir John. The stage was set, he was awaiting the rise of the curtain. Every now and again he would pause and look at his watch, awaiting zero hour. Then came those anxious moments, five minutes, four, three, two, one to go and then the sound of the guns in the opening barrage came over the air.

Sir John stopped and looking for a moment in the direction of the battle front, his anxiety relieved, he turned and slowly

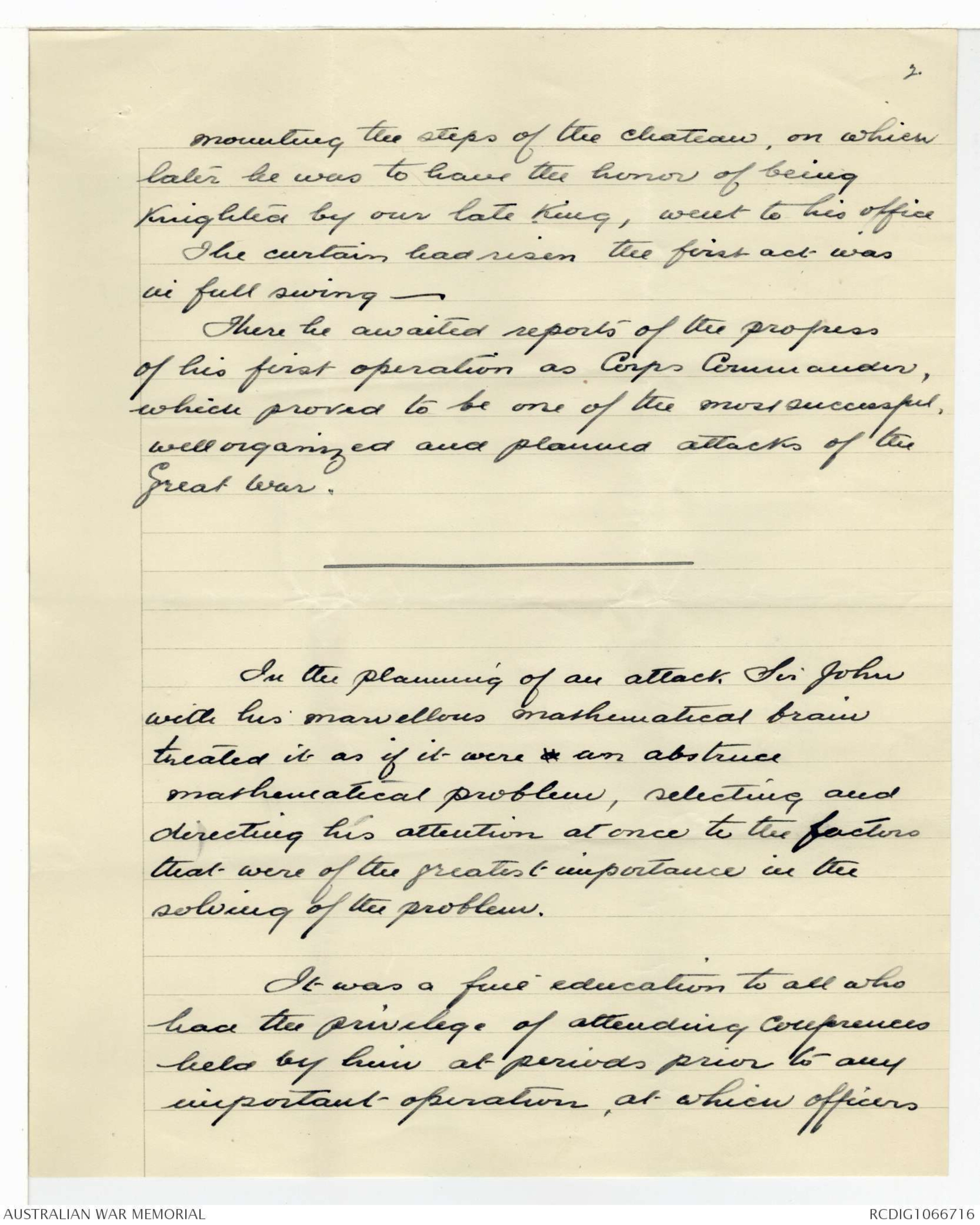

mounting the steps of the chateau, on which later he was to have the honor of being knighted by our late King, went to his office. The curtains had risen the first act was in full swing ---

There he awaited reports of the progress of his first operation as Corps Commander, which proved to be one of the most successful, well organized and planned attacks of the Great War.

-----------------------------------

In the planning of an attack Sir John with his marvellous mathematical brain treated it as if it were an abstruse mathematical problem, selecting and directing his attention at once to the factors that were of the greatest import5ance in the solving of the problem.

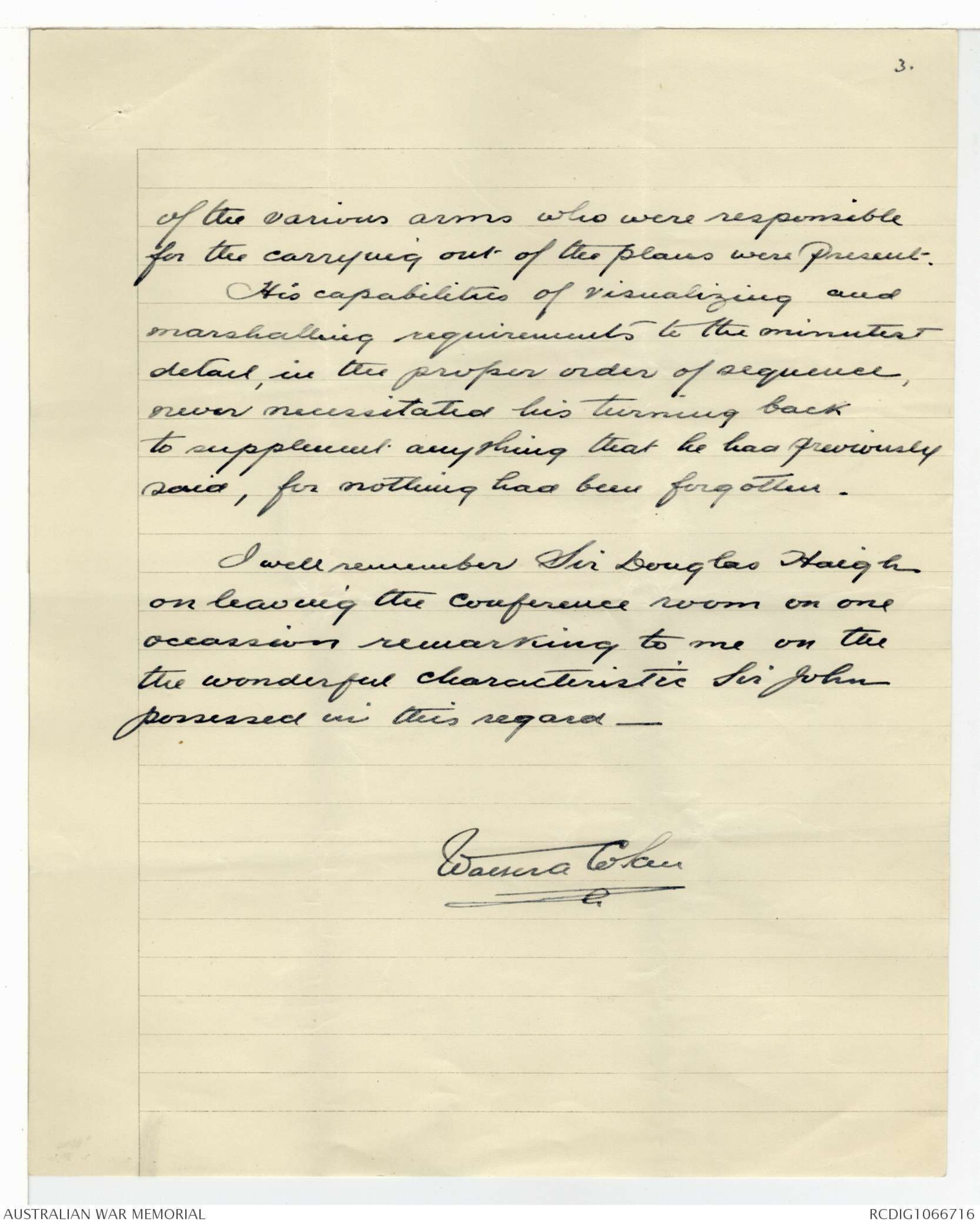

It was a fine education to all who had the privilege of attending conferences held by him at periods prior to any important operation, at which officers

of the various arms who were responsible for the carrying out of the plans were present.

His capabilities of visualizing and marshalling requirements to the minutest detail, in the proper order of sequence, never necessitated his turning back to supplement anything that he had previously said, for nothing had been forgotten.

I well remember Sir Douglas Haigh on leaving the conference room on one occassion remarking to me on the the wonderful characteristic Sir John possessed in this regard. ----

Walter A Coxan

Telephone

Central 11227

Box No. 531E

G.P.O. Melbourne

9 Apr 1937

RECEIVED

342 FLINDERS LAND

MELBOURNE

C.I.

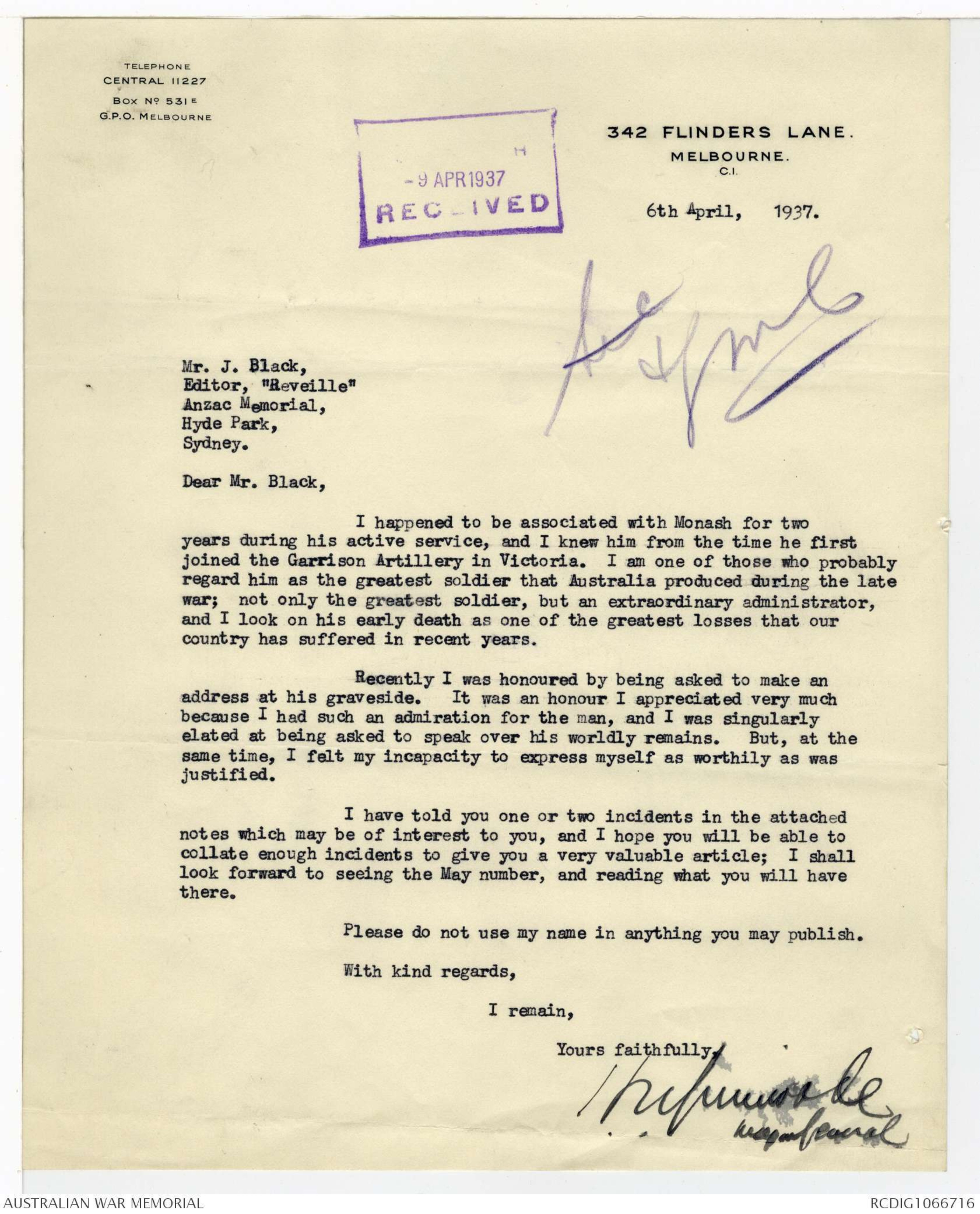

6 April, 1937

Mr. J. Black,

Editor, "Reveille"

Anzac Memorial,

Hyde Park,

Sydney.

Dear Mr. Black,

I happened to be associated with Monash for two years during his active service, and I knew him from the time he first joined the Garrison Artillery in Victoria. I am one of those who probably regard him as the greatest soldier that Australia produced during the late war; not only the greatest soldier, but an extraordinary administrator, and I look on his early death as one of the greatest losses that our country has suffered in recent years.

Recently I was honoured by being asked to make an address at his graveside. It was an honour I appreciated very much because I had such an admiration for the man, and I was singularly elated at being asked to speak over his worldly remains. But, at the same time, I felt my incapacity to express myself as worthily as was justified.

I have told you one or two incidents in the attached notes which may be of interest to you, and I hope you will be able to collate enough incidents to give you a very valuable article; I shall look forward to seeing the May number, and reading which you will have there.

Please do not use my name in anything you may publish.

With kind regards,

I remain,

Yours faithfully,

[[ ?? ]]

One attribute that always to my mind characterized the late General Sir John Monash was his fair and sincere outlook on life. He was a man of great attainments and great capabilities, but in all my experience of him - which extended over a long while - I never knew him to fail to give anyone a chance to show their value. I happened to be a Senior Staff Officer associated with him in 1916 '17 and early '18, and I never knew him during those very active years, do anything that savoured of unfairness to anyone. It did not matter what was going on at the time, if any officer or man had an idea on a subject, he could have it ventilated and Monash would give it his personal thought.

I remember two incidents - one during training in the middle of '16 when he found fault with a senior officer for not doing what he had been told by Divisional orders; when the senior officer drew attention to the fact that Monash's own staff had misled him, he immediately turned to that officer and said: "You happen to be senior to my staff, and can give them what particular hell you like".

On another occasion during active service in 1917 he found fault with that same officer for not carrying out Divisional Orders. The officer put a hypothetical case to Monash to protect himself, and he replied exactly in accordance with what this officer had done; when he realized this, he apologized and blackguarded his own Divisional Staff for issuing orders which demanded wrong service.

I give these two examples to show that Monash was fair and true to everyone. If a man failed him, he was down on him, but if the man served him well, he could not do enough for that man.

He was a wonder-ful man for absorbing details himself and explaining them to others. On one occasion during preparation for a very big offensive in 1917, I happened to be present, amongst a number of others, when the Commander in Chief visited Monash's Headquarters to learn something of the proposed operations. The room that he used as an office was lined with maps and Monash went through all the activities of the different arms under him - what they were doing, and what they proposed to do - during which time I could see General Haig's eyes glued on him taking in everything he was being told. At the end of the short address, Monash said: "I have my Senior Officers here from all these Commands to tell you anything you may wish to know, Sir". General Haig in his nice,

-2-

gentlemanly way thanked Monash and said that he did not think there was anything that Monash had left unsaid, and the officers who were gathered there to answer for their actions, were thanked for being present and sent away with his very best wishes.

It was marvellous the thoroughness that Sir John Monash put into all the work he did; it was wonderful that he had the time available to do everything so thoroughly as he did it. He was able to work quickly and get everyone else around him to absorb details just as quickly as he was able to describe them. An English officer attached to his Division was very struck with the way the Divisional Commander knew everything that happened in the whole of his command, as in those days the British Generals in command left a great deal of detail to their subordinates. General Monash left responsibility to his subordinates, but helped them the whole time by advising them what was required.

I do not think there was any man under Monash's command who did not have the very highest regard for him, amounting almost to affection; they certainly would not have hesitated to lay down their lives for him or do anything to further him in any way possible.

[[ (??) ]]

April 6th 1937

Sam scott

Sam scottThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.