Charles E W Bean, Diaries, AWM38 3DRL 606/276/1 - 1928-1937 - Part 15

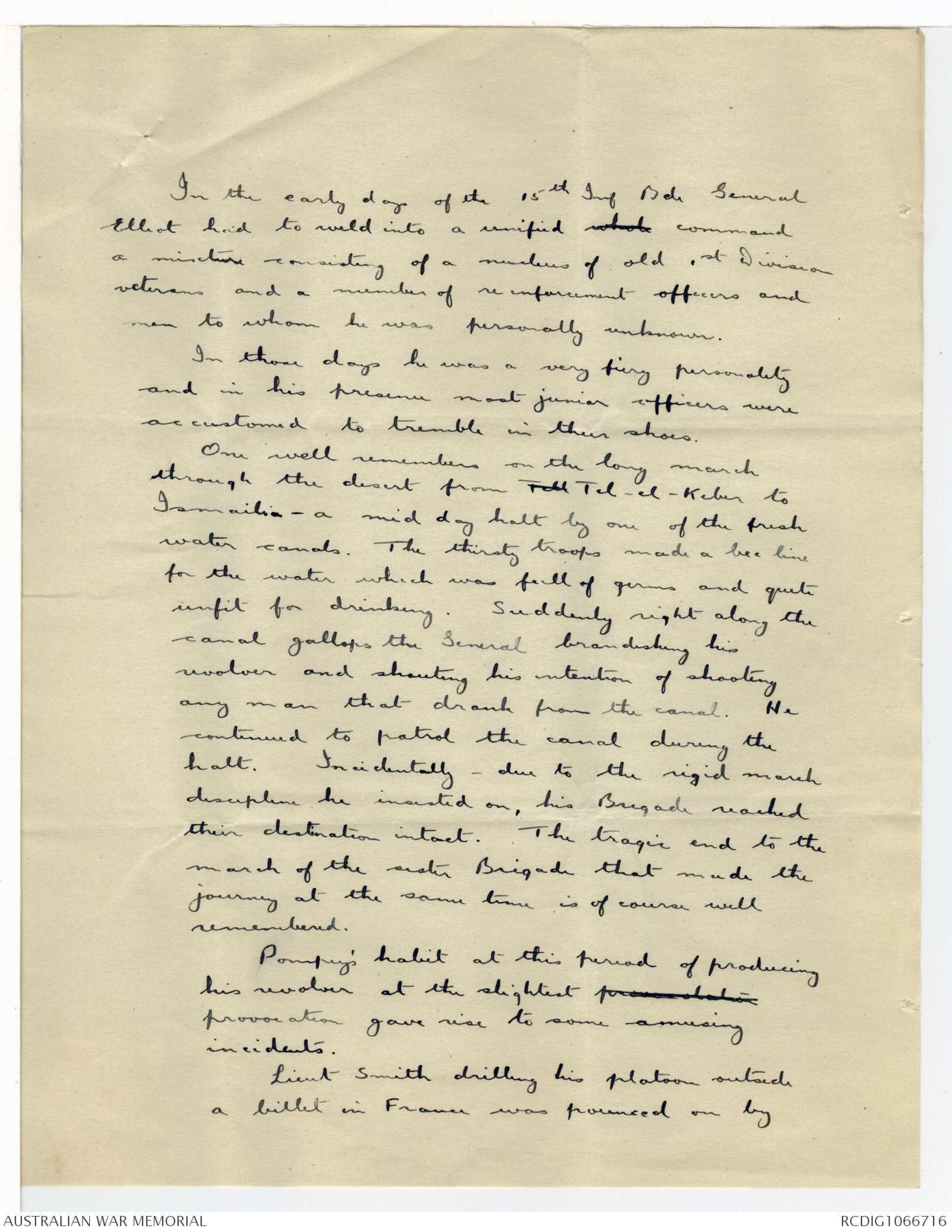

In the early days of the 15th Inf Bde General

Elliot had to weld into a unified whole command

a mixture consisting of a nucleus of old 1st Division

veterans and a number of reinforcement officers and

men to whom he was personally unknown.

In those days he was a very fiery personality

and in his presence most junior officers were

accustomed to tremble in their shoes.

One well remembers on the long march

through the desert from Tell Tel-el-Kebir to

Ismailia - a mid day halt by one of the fresh

water canals. The thirsty troops made a bee line

for the water which was full of germs and quite

unfit for drinking. Suddenly right along the

canal gallops the General brandishing his

revolver and shouting his intention of shooting

any man that drank from the canal. He

continued to patrol the canal during the

halt. Incidentally - due to the rigid march

discipline he insisted on, his Brigade reached

their destination intact. The tragic end to the

march of the sister Brigade that made the

journey at the same time, is of course will

remembered.

Pompey's habit at this period of producing

his revolver at the slightest prxxxxxxxx

provocation gave rise to some amusing

incidents.

Lieut Smith drilling his platoon outside

a billet in France was pounced on by

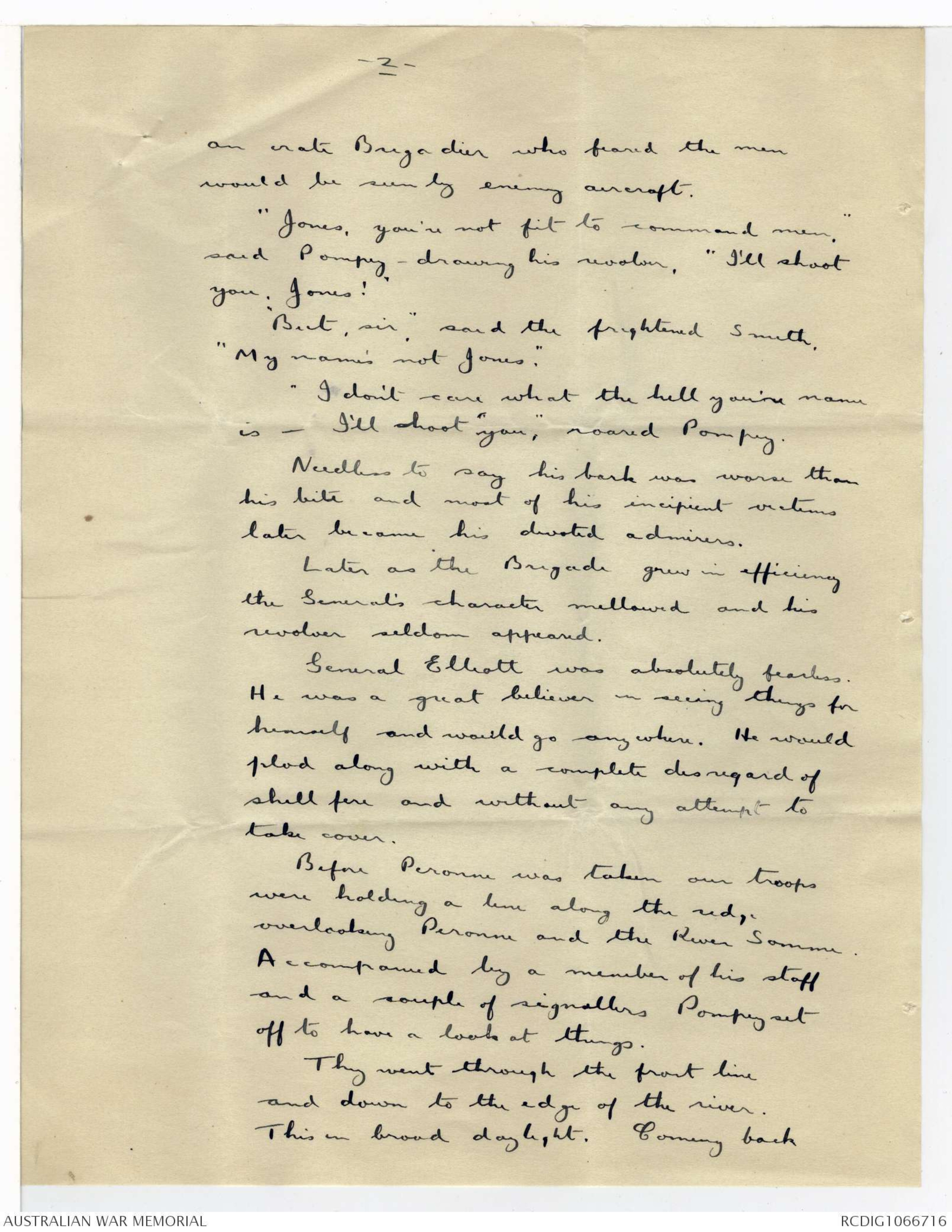

-2-

an irate Brigadier who feared the men

would be seen by enemy aircraft.

"Jones, you're not fit to command men,"

said Pompey - drawing his revolver, "I'll shoot

you, Jones!"

"But, sir," said the frightened Smith,

"My name's not Jones."

"I don't care what the hell you're name

is - I'll shoot "you," roared Pompey.

Needless to say his bark was worse than

his bite and most of his incipient victims

later became his devoted admirers.

Later as the Brigade grew in efficiency

the General's character mellowed and his

revolver seldom appeared.

General Elliott was absolutely fearless.

He was a great believer in seeing things for

himself and would go anywhere. He would

plod along with a complete disregard of

shell fire and without any attempt to

take cover.

Before Peronne was taken our troops

were holding a line along the ridge

overlooking Peronne and the River Somme.

Accompanied by a member of his staff

and a couple of signallers Pompey set

off to have a look at things.

They went through the front line

and down to the edge of the river.

This in broad day light. Coming back

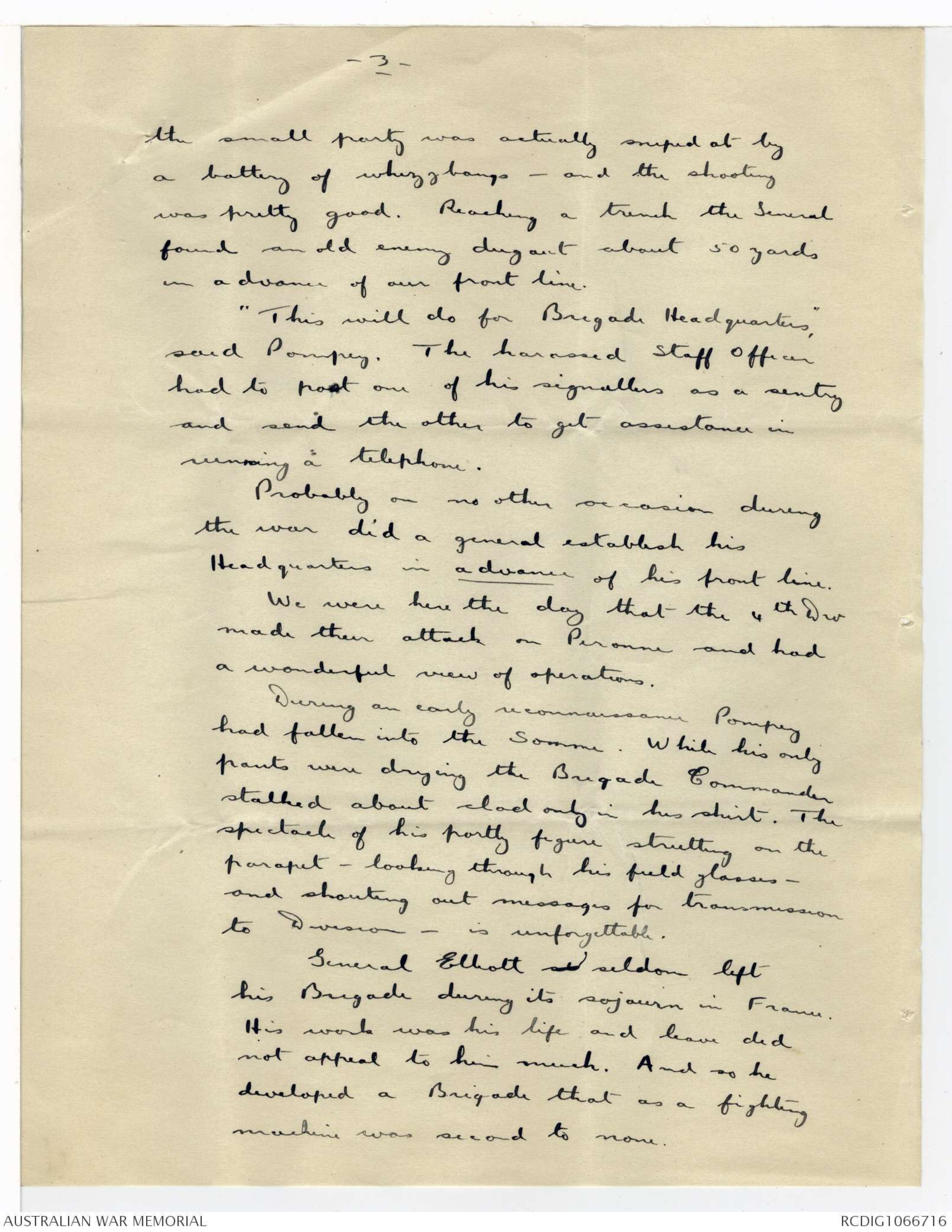

-3-

the small party was actually sniped at by

a battery of whizzbangs - and the shooting

was pretty good. Reaching a trench the General

found an old enemy dugout about 50 yards

in advance of our front line.

"This will do for Brigade Headquarters."

said Pompey. The harassed Staff Officer

had to post one of his signallers as a sentry

and send the other to get assistance in

running a telephone.

Probably on no other occasion during

the war did a general establish his

Headquarters in advance of his front line.

We were here the day that the 4th Div

made their attack on Peronne and had

a wonderful view of operations.

During an early reconnaissance Pompey

had fallen into the Somme. While his only

pants were drying the Brigade Commander

stalked about clad only in his shirt. The

spectacle of his portly figure strutting on the

parapet - looking through his field glasses -

and shouting out messages for transmission

to Division - is unforgettable.

General Elliott se seldom, left

his Brigade during its sojourn in France.

His work was his life and leave did

not appeal to him much. And so he

developed a Brigade that as a fighting

machine was second to none.

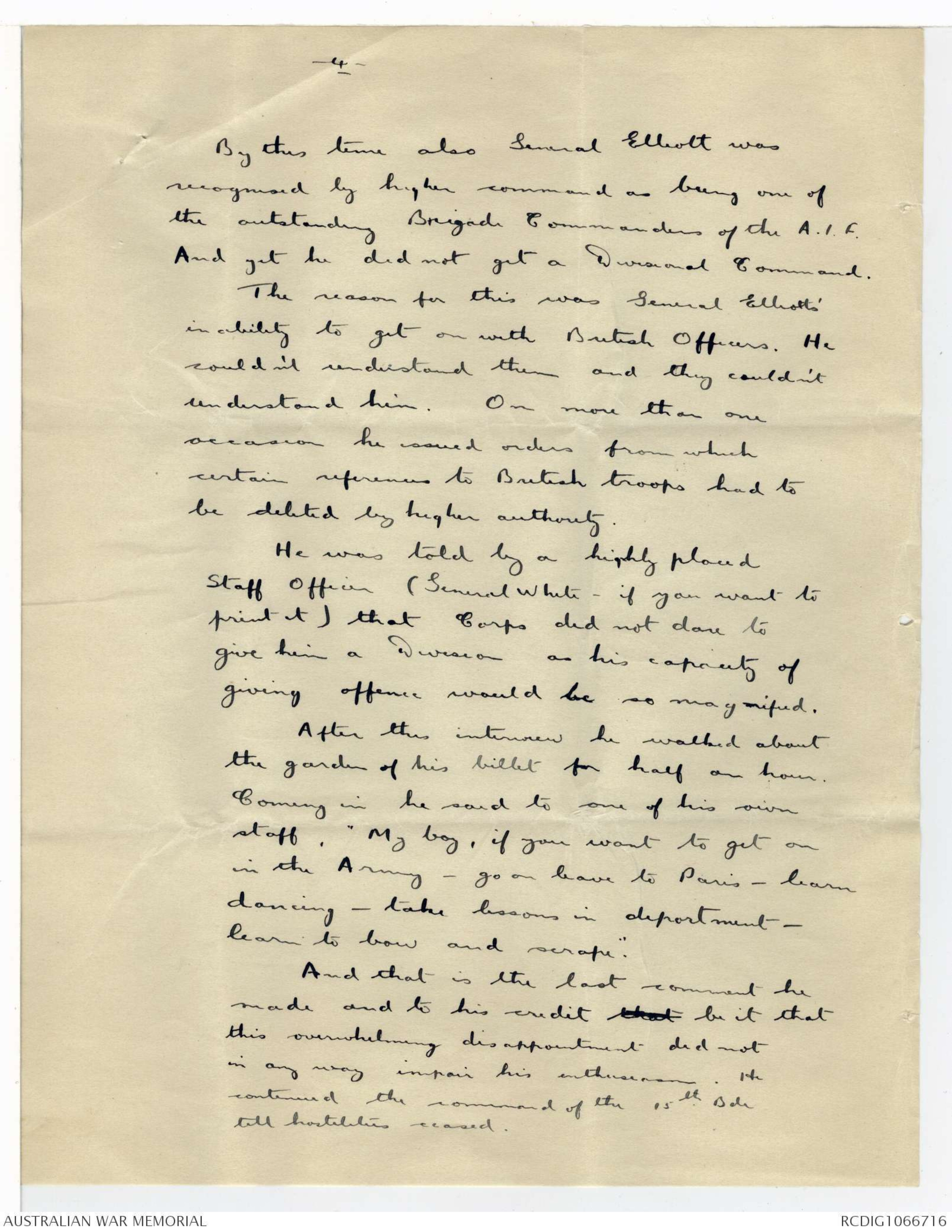

-4-

By this time also General Elliott was

recognised by higher command as being one of

the outstanding Brigade Commanders of the A.I.F.

And yet he did not get a Divisional Command.

The reason for this was General Elliotts'

inability to get on with British Officers. He

couldn't understand them and they couldn't

understand him. On more than one

occasion he issued orders from which

certain references to British troops had to

be deleted by higher authority.

He was told by a highly placed

Staff Officer (General White - if you want to

print it) that Corps did not dare to

give him a Division as his capacity of

giving offence would be so magnified.

After this interview he walked about

the garden of his billet for half on hour.

Coming in he said to one of his own

staff. "My boy, if you want to get on

in the Army - go on leave to Paris - learn

dancing - take lessons in deportment -

learn to bow and scrape."

And that is the last comment he

made and to his credit that be it that

this overwhelming disappointment did not

in any way impair his enthusiasm. He

continued the command of the 15th Bde

till hostilities ceased.

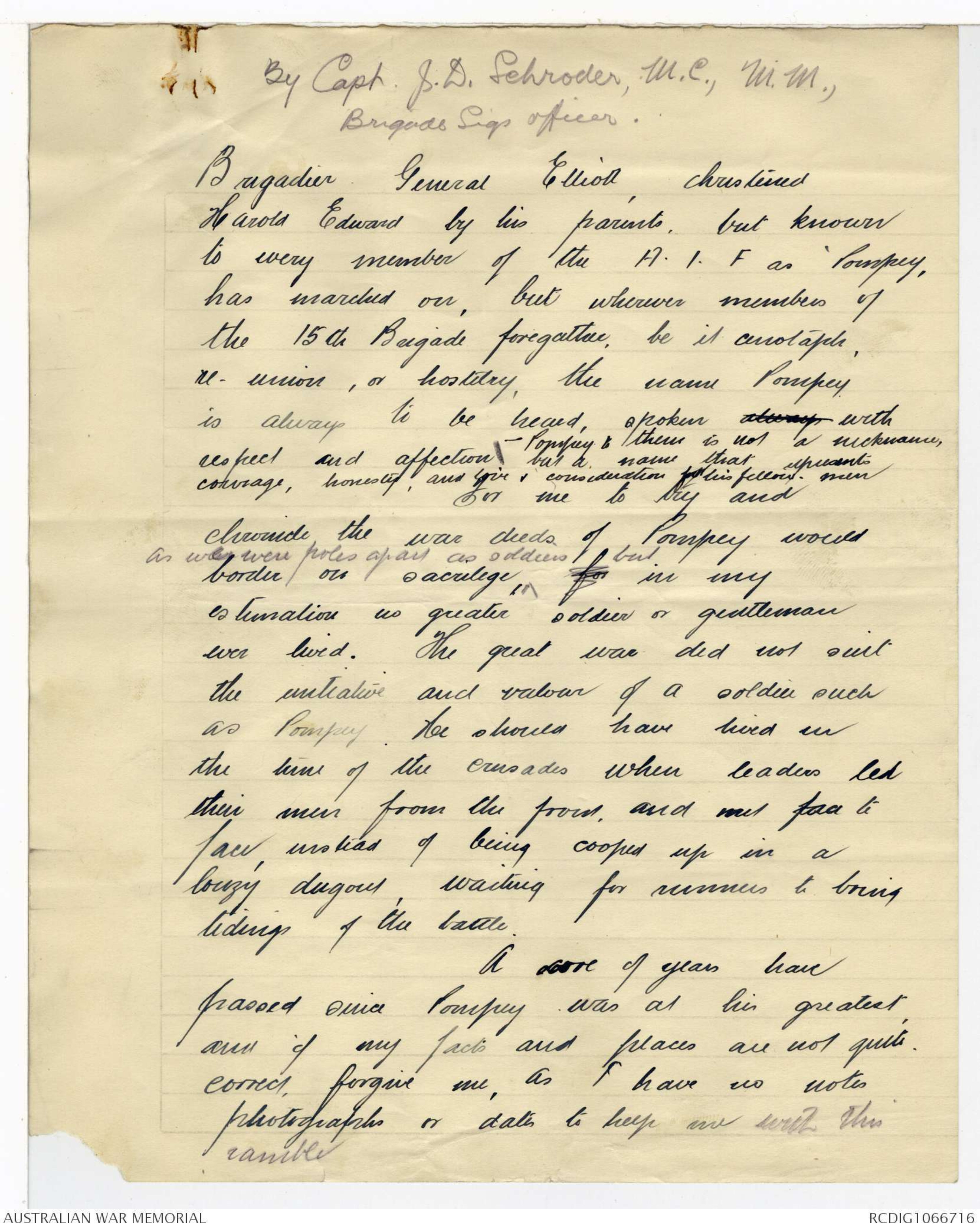

By Capt. J.D. Schroder, M.C, M.M.,

Brigade Sigs officer.

Brigadier General Elliott, christened

Harold Edward by his parents, but known

to every member of the A.I.F. & as 'Pompey,

has marched on, but wherever members of

the 15th Brigade foregather, be it cenotaph,

re-union, or hostelry, the name Pompey

is always to be heard, spoken always with

respect and affection - Pompey to them is not a nickname, but a name that represents

courage, honesty and love & consideration for his fellow-men

For me to try and

chronicle the war deeds of Pompey would

border on sacrilege, ^as we were poles apart as soldiers but for in my

estimation no greater soldier or gentleman

ever lived. The great war did not suit

the initiative and valour of a soldier such

as Pompey. He should have lived in

time of the crusades when leaders led

their men from the front, and met face to

face, instead of being cooped up in a

lousy dugout, waiting for runners to bring

tidings of the battle.

A score of years have

passed since Pompey was at his greatest,

and if my facts and places are not quite

correct, forgive me, as I have no notes

photographs or dates to keep me with this

ramble

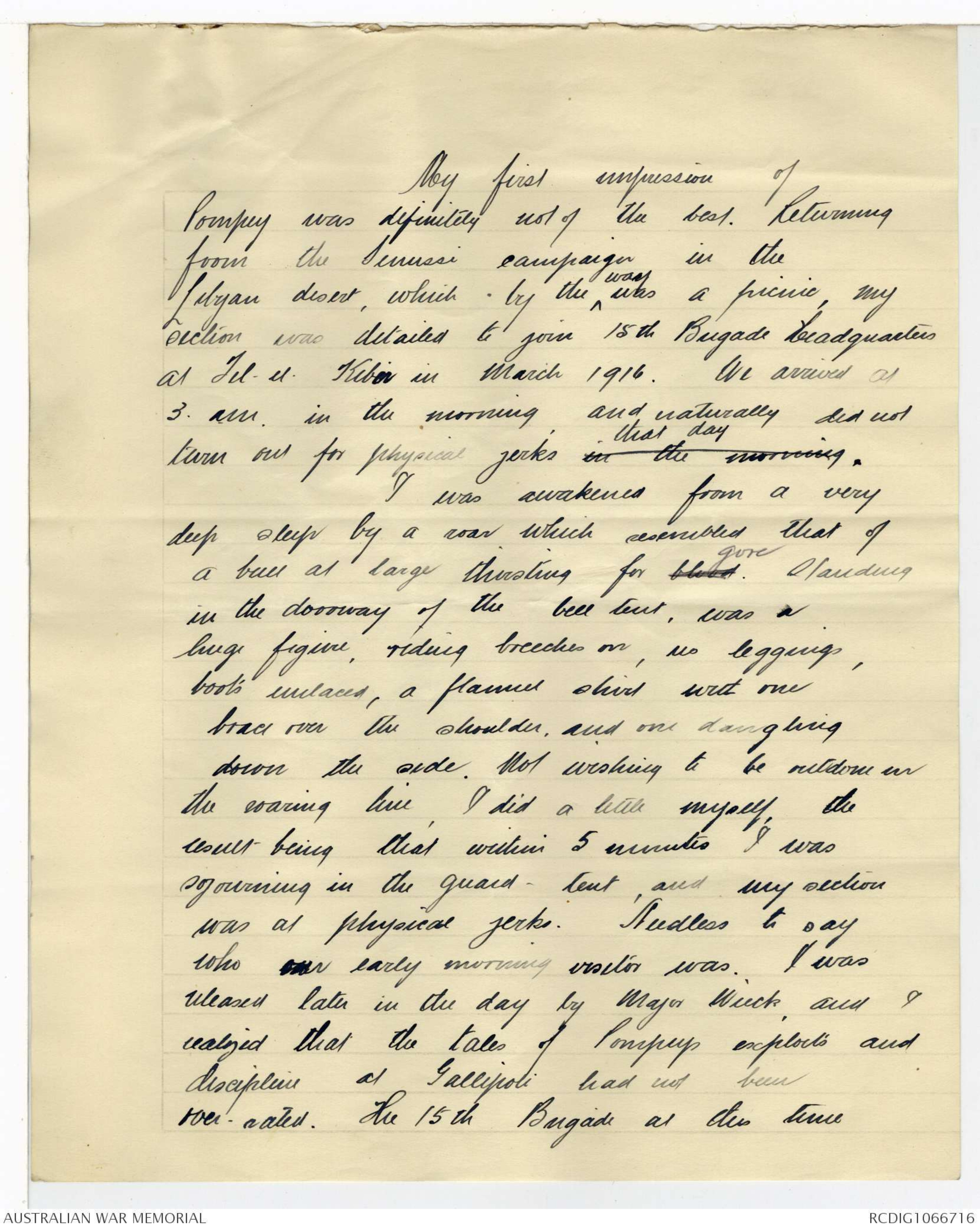

My first impression of

Pompey was definitely not of the best. Returning

from the Senussi campaign in the

Libyan desert, which by the ^way was a picnic, my

section was detailed to join 15th Brigade Headquarters

at Tel-el-Kebir in March 1916. We arrived at

3. am. in the morning and naturally did not

turn out for physical jerks in the morning that day.

I was awakened from a very

deep sleep by a roar which resembled that of

a bull at large thirsting for blood gore. Standing

in the doorway of the bell tent, was a

huge figure, riding breeches on, no leggings,

boots unlaced, a flannel shirt with one

brace over the shoulder, and one dangling

down the side. Not wishing to be outdone in

the roaring line, I did a little myself, the

result being that within 5 minutes I was

sojourning in the guard - tent, and my section

was at physical jerks. Needless to say

who our early morning visitor was. I was

released later in the day by Major Wieck and I

realized that the tales of Pompeys exploits and

discipline at Gallipoli had not been

over-rated. The 15th Brigade at this time

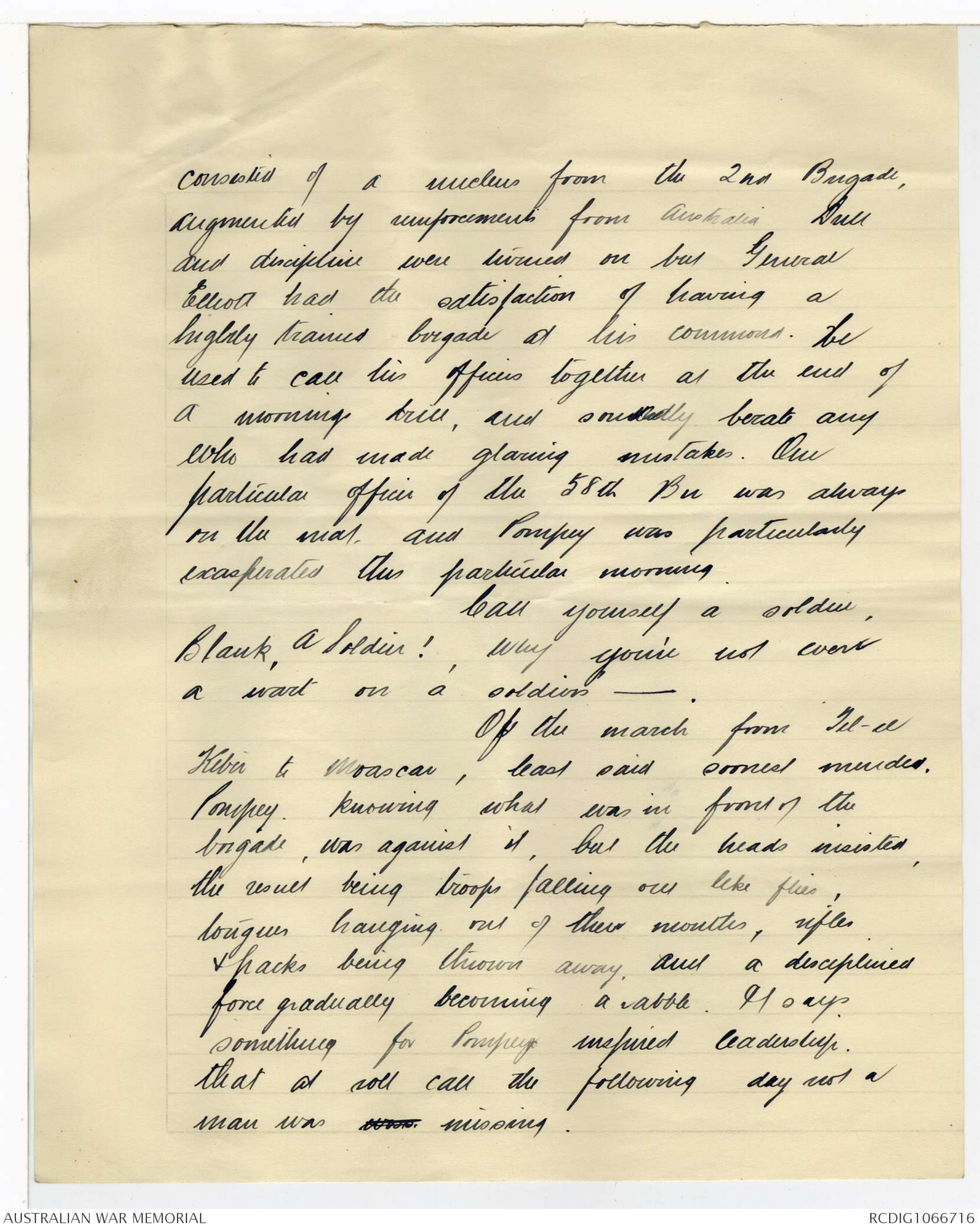

consisted of a nucleus from the 2nd Brigade,

augmented by reinforcements from Australia. Drill

and discipline were [[turned?]] on but General

Elliott had the satisfaction of having a

highly trained brigade at his command. He

used to call his officers together at the end of

a morning drill, and soundly berate any

who had made glaring mistakes. One

particular officer of the 58th Bn was always

on the mat and Pompey was particularly

exasperated this particular morning.

Call yourself a soldier,

Blank, a Soldier! Why you're not even

a wart on a soldiers' _____.

Of the march from Tel-el

Kebir to Moascar, least said soonest mended.

Pompey, knowing what was in front of the

brigade, was against it, but the heads insisted,

the result being troops falling over like flies,

tongues hanging out of their months, rifles

& packs being thrown away, and a disciplined

force gradually becoming a rabble. It says

something for Pompeys inspired leadership,

that at roll call the following day not a

man was was missing.

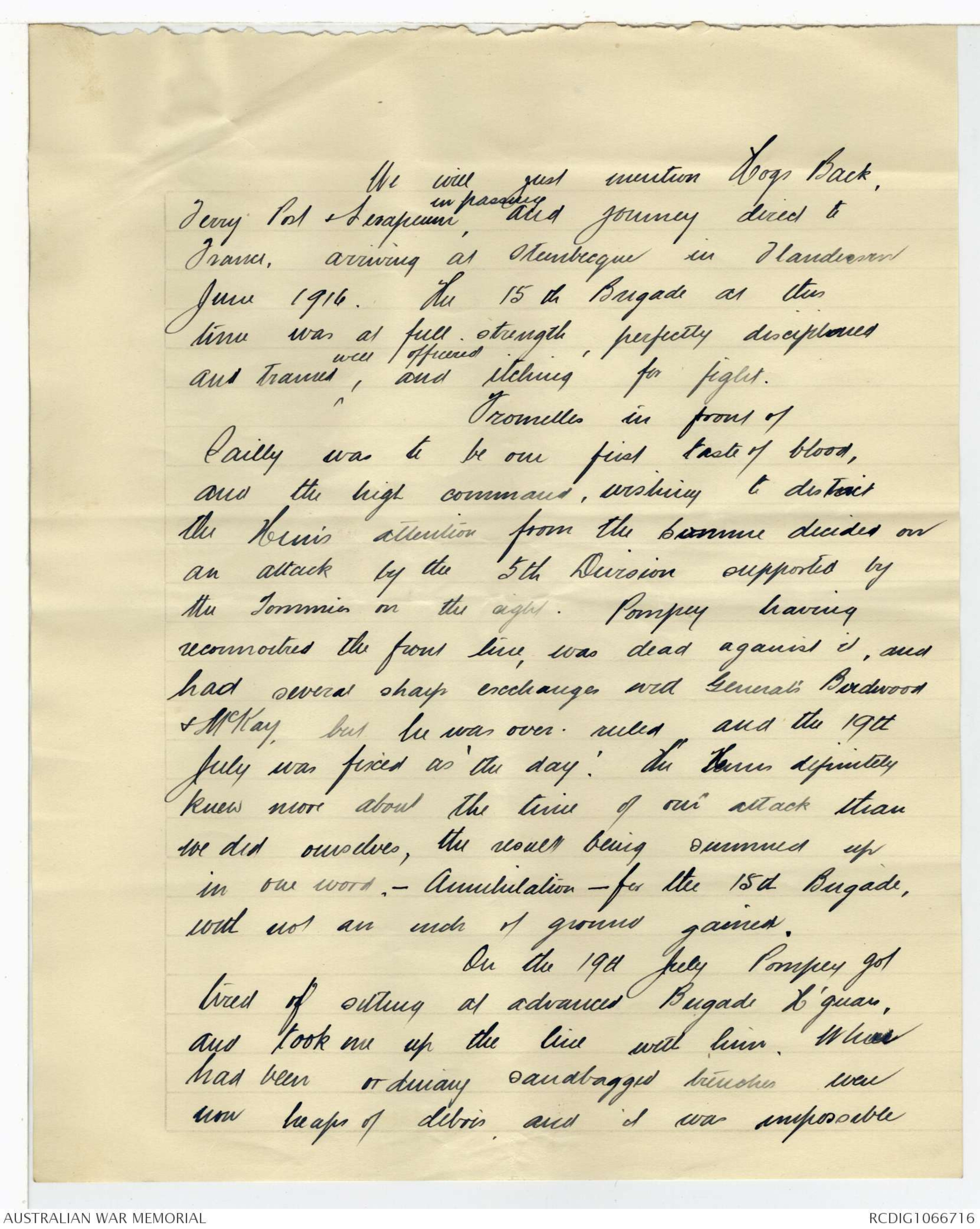

We will just mention Hogs Back.

Ferry Post & Serapeum in passing and journey direct to

France, arriving at Steenbecque in Flanders in

June 1916. The 15th Brigade at this

time was at full strength, perfectly disciplined

and trained ^well, officered and itching for fight.

Fromelles in front of

Sailly was to be our first taste of blood,

and the high command, wishing to distract

the Hun's attention from the Somme decided on

an attack by the 5th Division supported by

the Tommies on the right. Pompey having

reconnoitred the front line, was dead against it, and

had several sharp exchanges with General's Birdwood

& McKay, but he was over-ruled and the 19th

July was fixed as 'the day'. The Huns definitely

knew more about the time of our attack than

we did ourselves, the result being summed up

in one word - Annihilation - for the 15th Brigade

with not an inch of ground gained.

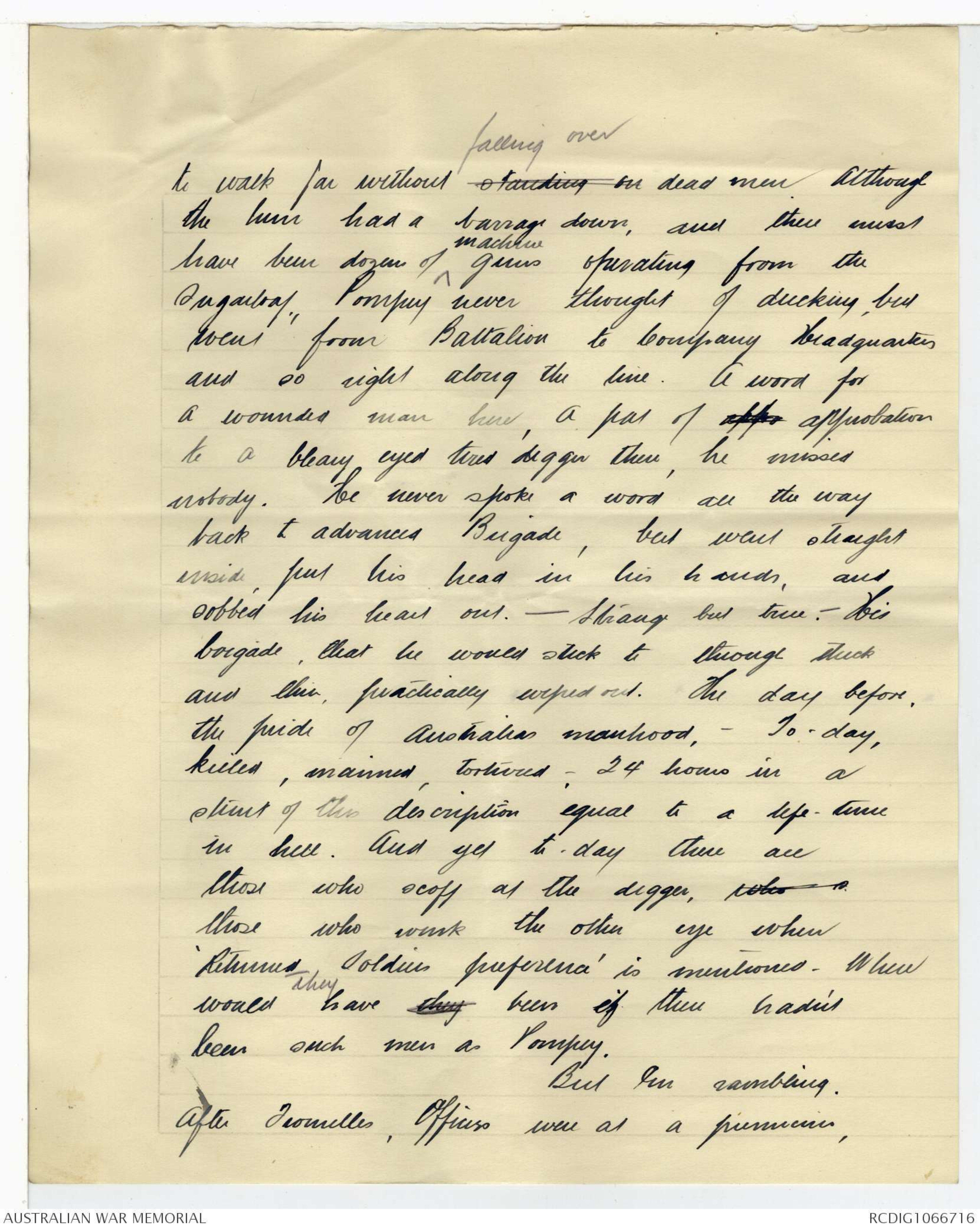

On the 19th July Pompey got

tired of sitting at advanced Brigade H'quars,

and took me up the line will him. Where

had been ordinary sandbagged trenches were

now heaps of debris, and it was impossible

to walk far without standing on falling over dead men. Although

the hum had a barrage down, and there must

have been dozen of ^machine guns operating from the

Sugarloaf, Pompey never thought of ducking but

went from Battalion to Company Headquarters

and so right along the line. A word for

a wounded man here, a pat of appo approbation

to a bleary eyed tired digger there, he missed

nobody. He never spoke a word all the way

back to advances Brigade, but went straight

inside, put his head in his hands, and

sobbed his heart out. - Strange but true - His

brigade, that he would stick to through thick

and thin, practically wiped out. The day before

the pride of Australias manhood, - To-day,

killed, maimed, tortured, - 24 hours in a

stunt of this description equal to a life-time

in hell. And yet to-day there are

those who scoff of the digger, who w

those who wink the other eye when

'returned soldiers preference' is mentioned. When

would they have they been if there hadn't

been such men as Pompey.

But Im rambling.

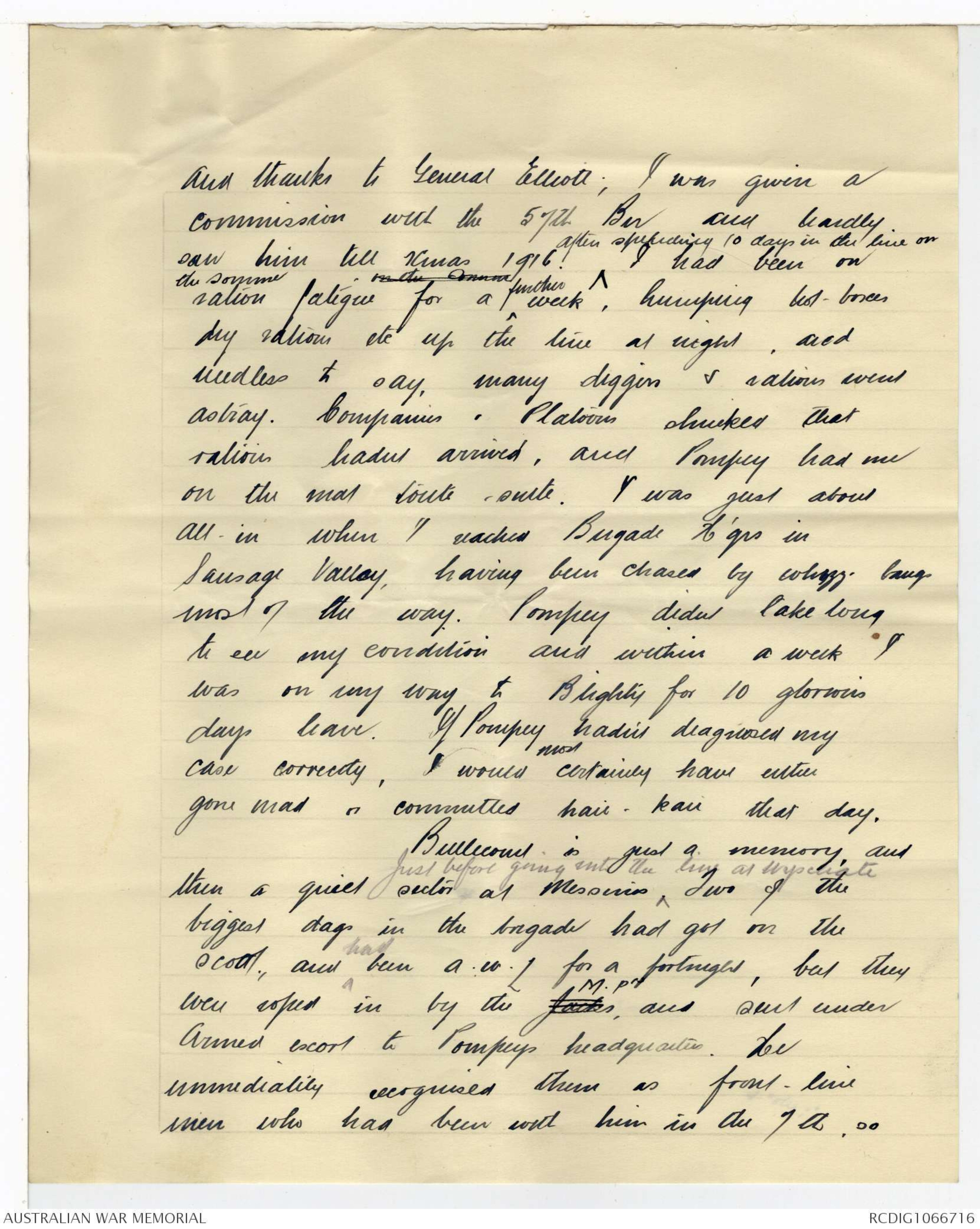

After Fromelles, Officers were at a premium,

and thanks to General Elliott; I was given a

commission with the 57th Bn and hardly

saw him till Xmas 1916. ^After spending 10 days in the line on the Somme I had been on

ration fatigue on the Somme for a ^further week, humping hot-boxes

dry rations etc up the line at night, and

needless to say, many diggers & rations went

astray. Companies. Platoons shucked that

rations hadnt arrived, and Pompey had me

on the mat toute-suite. I was just about

all-in when I reached Brigade H'qrs in

Sausage Valley, having been chased by whizz-bangs

most of the way. Pompey didnt take long

to see my condition and within a week I

was on my way to Blighty for 10 glorious

days leave. If Pompey hadn't diagnosed my

case correctly, I would most certainly have either

gone mad or committed hari-kari that day.

Bellecourt is just a memory and

then a quiet sector at Messines ^just before going into the line at Wyschate. Two of the

biggest days in the brigade had got on the

scout, and ^had been A.W.L for a fortnight, but they

were roped in by the Jacks M.P, and sent under

armed escort to Pompeys headquarters. He

immediately recognised them as front-line

men who had been with him in the 7th, so

Sam scott

Sam scottThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.