Charles E W Bean, Diaries, AWM38 3DRL 606/274B/1 - 1918 - 1939 - Part 5

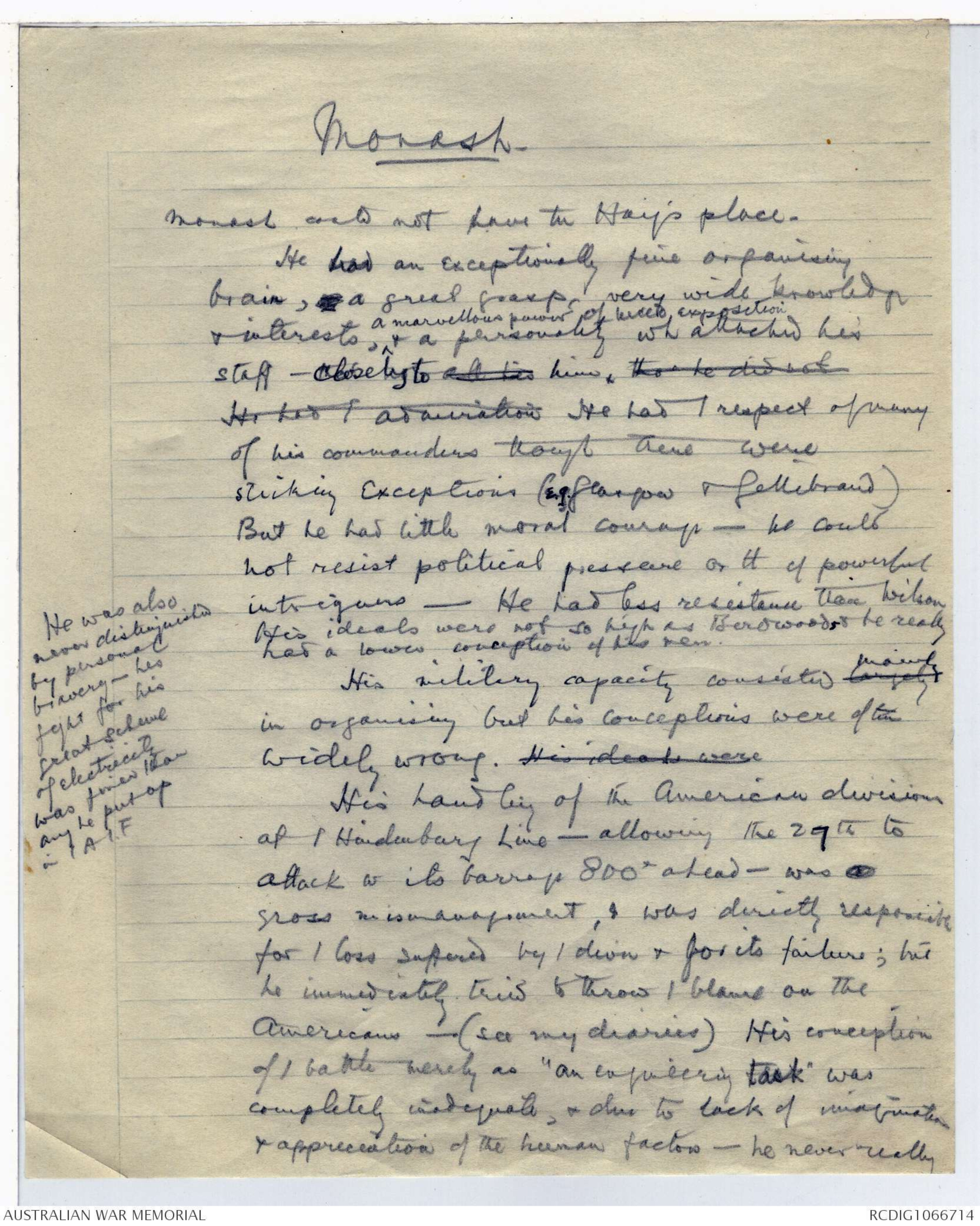

Monash.

Monash could not have tn Haig's place.

He had an exceptionally fine organising

brain, x a great grasp, very wide knowledge

& interests, ^a marvellous power of lucid exposition & a personality wh attached his

staff - closely to all his him. tho he did notHe had / admiration He had / respect of many

of his commanders though there were

striking exceptions (eg. Glasgow and Gellibrand)

But he had little moral courage - he could

not resist political pressure or tt of powerful

intriguers - He had less resistance than Wilson

His ideals were not so high as Birdwoods, & he really

had a lower conception of his men.

[*He was also

never distinguished

by personal

bravery - his

fight for his

great scheme

of electricity

was finer than

any he put up

in / A I.F*]

His military capacity consisted largely mainly

in organising but his conceptions were often

widely wrong. HIs ideals were

His handling of the American division

at / Hindenburg Line - allowing the 27th to

attack w its barrage 800x ahead - was a

gross mismanagement, & was directly responsible

for / loss suffered by / divn & for its failure; but

he immediately tried to throw / blame on the

Americans —(see my diaries) His conception

of / battle merely as "an engineering task" was

completely inadequate, & due to lack of imagination

& appreciation of the human factors - he never really

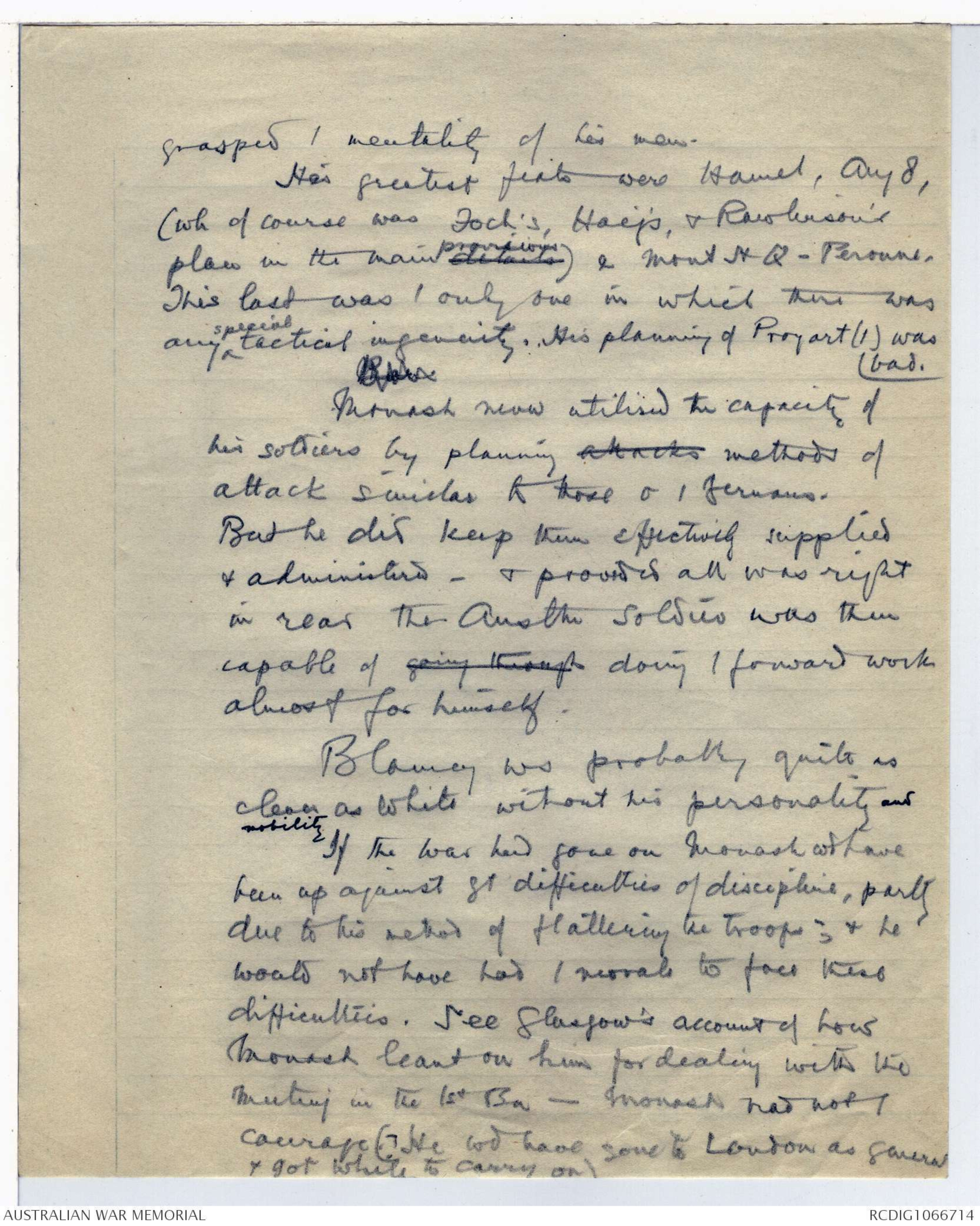

grasped / mentality of his men.

His greatest feats were Hamel, Aug 8,

(wh of course was Foch's, Haig's, & Rawlinson's

plan in the main details provisions) & Mont St Q - Perrone.

This last was / only one in which there was

any ^special tactical ingenuity. His planning of Proyart (1) was bad .

Bxxx

Monash never utilised the capacity of

his soldiers by planning attacks methods of

attack similar to those o / Germans.

But he did keep them effectively supplied

& administered - & provided all was right

in rear the Austln soldier was then

capable of going through doing / forward work

almost for himself.

Blamey ws probably quite as

clear as White without his personality and

mobility.

If the war had gone on Monash wd have

been up against gt difficulties of discipline, partly

due to his method of flattering the troops; & he

would not have had / morals to face these

difficulties. See Glasgow's account of how

Monash leant on him for dealing with the

mutiny in the 1st Bn - Monash had not /

courage (He wd have gone to London as General

& got White to carry on)

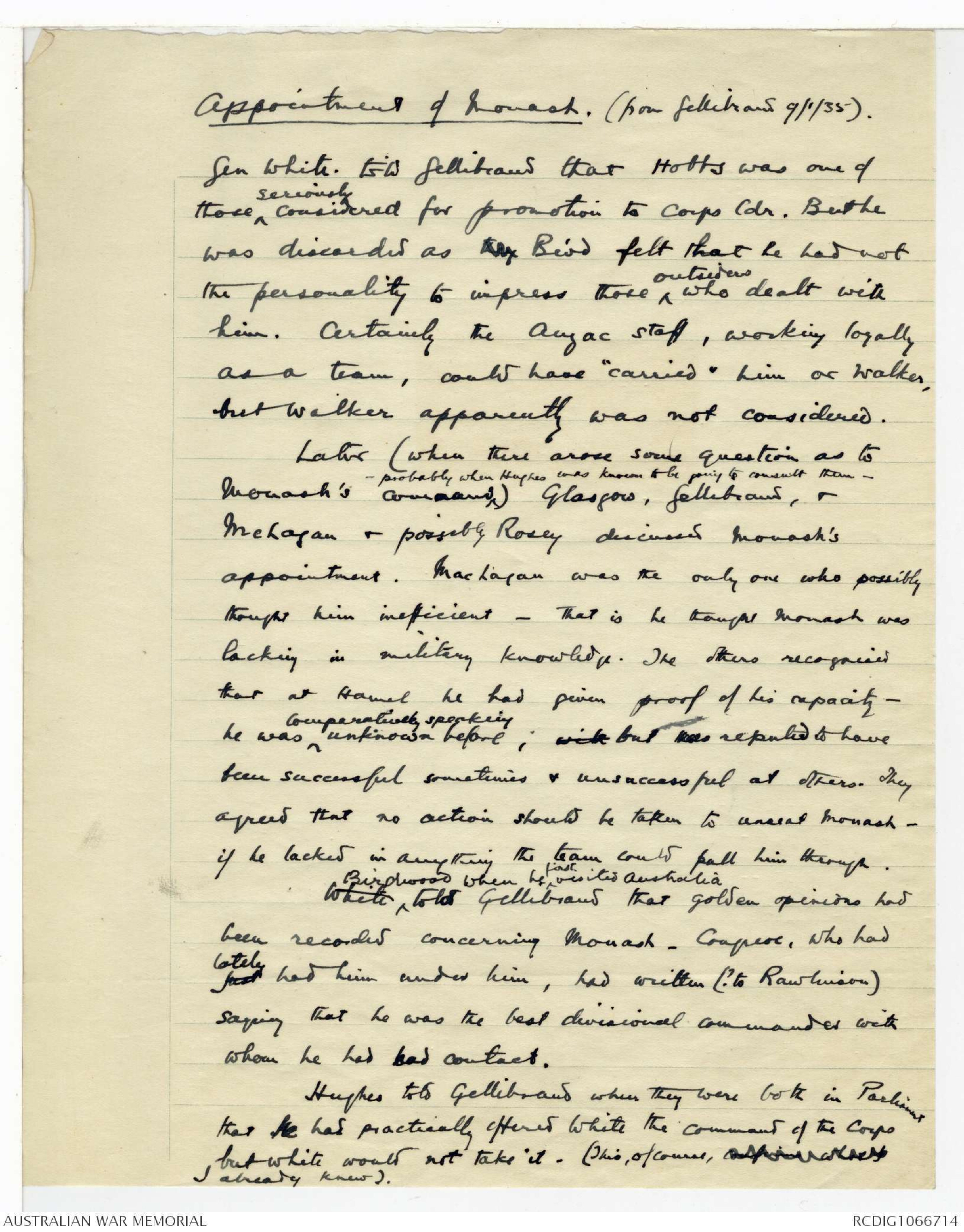

Appointment of Monash. (from Gellibrand 9/1/35).

Gen White. told Gellibrand that Hobbs was one of

those ^seriously considered for promotion to Corps Cdr. But he

was discarded as they Bird felt that he had not

the personality to impress those ^outsiders who dealt with

him. Certainly the Anzac staff, working loyally

as a team, could have "carried" him or Walker,

but Walker apparently was not considered.

Later (when there arose some question as to

Monash's command ^- probably when Hughes was known to be going to consult them -) Glasgow, Gellibrand, &

McLagan & possibly Rosey discussed Monash's

appointment. MacLagan was the only one who possibly

thought him inefficient - That is he thought Monash was

lacking in military knowledge. The others recognised

that at Hamel he had given proof of his capacity -

he was ^Comparatively speaking unknown before; with but was reputed to have

been successful sometimes & unsuccessful at others. They

agreed that no action should be to taken to unseat Monash -

if he lacked in anything the team could pull him through.

White^Birdwood when he^first visited Australia told Gellibrand that golden opinions had

been recorded concerning Monash. [[Coupere?]], who had

Just lately had him under him, had written(? to Rawlinson)

saying that he was the best divisional commander with

whom he had had contact.

Hughes told Gellibrand when they were both in Parliament

that he had practically offered White the Command of the Corps

but White would not take it . (This, of course, xxxxxxx xx xxx

I already knew).

S. M. Herald

6/7/34

6/7/34 LATE GENERAL MONASH.

Commenting on Mr. Lloyd George's reference

in his memoirs to his fruitless wartime search

for a suitable British Commander-in-Chief,

and that "since the war he had been told by

men, whose judgment he valued, that the only

soldier thrown up by the war on the British

side possessing the necessary qualities was a

dominion General," the "Evening Standard"

diarist says: "That soldier was the late General

Monash whose military genius came as

naturally to him as to Napoleon's Generals."

GENERAL MONASH.

Some Sidelights.

(BY NORMAN CAMPBELL.)

A man so various that he seemed to be not one

but all mankind's epitome.

In his informative article on the 'War

Letters of General Monash," R.G.H. says: "When,

after the war, he led 5000 picked men through

London, it must have been truly the most

splendid moment of his career."

Once I asked General Monash that very

question, "What was the proudest moment of

your career?"

He knit his brows for a moment in his

characteristic way, and then said: "I've had

two proud moments which I recall. One

was when I called a council of war just before

we broke the Hindenburg line, the other was

when I had a yarn with Ned Kelly."

[*Miss Monash tells me she knows

nothing of this. Apparently J. Monash

was then in Melbourne & had been

for 2 yrs a long time. She would surely have

heard of it if it were true. C.E.W.B.*]

Of course, I asked for details as to both

events. "I was a school kid at Jerilderie,"

explained Sir John, "when Ned Kelly and his

gang took possession of the township and held

it for three days. That was in February,

1879. Like all the other youngsters in the

place, I was keen to get a glimpse of the

famous outlaw. So I went round in the

morning, rather early, to the hotel which Ned had

made his headquarters, and saw him come

out of the place and squat on the verandah's

edge to have a smoke. He beckoned me

over, asked me my name, and so forth, and

then gave me a short lecture. A Sunday school

superintendent couldn't have given me

better advice as to human conduct.

The council of war I called on the Western

Front on the occasion I have mentioned

was a ticklish business. I wasn't afraid that

I couldn't convince my Australian generals

that I was right but several British generals

were also present. Each one of these was a

professional soldier. Each had been born

into the cast-iron traditions of the British

Army. Each subconsciously felt some disdain

for my views - I, a mere citizen soldier. Well,

I had to convince these men that my plan

was the best possible in the circumstances, and

not only that, but send them away from that

council enthusiastic about it, and eager to

carry it out. I did it," he concluded simply,

"and that, I think, was really the proudest

moment of my life."

THE GALLIPOLI EVACUATION.

I once sat next Sir John at a long and

rather dreary political banquet, and as usual

he chatted freely on all kinds of things. The

subject of the evacuation of Gallipoli came up,

and he told me many details concerning that

masterly operation. "We had strict orders

to leave no scrap of writing - and not even

a newspaper - behind. Well, my party was

almost the last to leave, and, just as we

had got to the embarkation point, I suddenly

remembered that I had left all my private

papers and diary-letters in my dugout, three

miles away. I simply told the others to

'carry on', and dashed back through the night

to retrieve my precious documents. I ran

all the way, got my papers all right, and

then dashed back safely. The point of the

story is that there was not a man between me

and the entire Turkish army."

One pictures the sturdy little figure scudding

through the night! A few days later

I wrote and asked Sir John if he would allow

me to print the story. Here is his reply:

"Thanks for your letter of the 18th inst.,

and for the enclosure from your little niece.

Please tell her that I appreciate her letter

of thanks just as much as she could have

appreciated my autograph.

"Regarding that story I told you about the

night of the evacuation, by all means use it

if it is of interest to you. I should add

that the despatch case which I went back

to find contained not only the whole of the

orders for the evacuation - which we had

been strictly enjoined to destroy after perusal,

but which I had wickedly hung on to as an

historical souvenir - but also contained the

diary-letter to my folk at home, which

contained a detailed account of everything that

had happened in my part of the Anzac

position from the date - some ten days previously

- when senior officers first became aware,

confidentially, that the evacuation was to

take place.

"It would have been very disastrous if

all these documents had fallen into enemy

hands.

"As regards the diary-letter above referred

to, I managed (again against orders) to get

this smuggled into Australia so as to escape

censorship, and subsequently, during 1916,

many copies of same were made and widely

circulated among my acquaintances and

interested strangers.

"I hope that in writing about these matters,

you do not deal too hardly with me for

"disobeying orders.' "

THE KING AND THE AUTOGRAPH

BOOK.

The allusion to a letter from my little

niece recalls another matter of some interest.

I had asked the General for his autograph

for this little girl, and he willingly gave it.

"You know," he said, "I am very fond of

collecting autographs myself. I have a book

containing specimens from every notability

associated with the war - a most catholic

collection. One day in France I was in my

H.Q., and this autograph book was lying

on the table, when the King strolled in.

Casually, he picked up the book and glanced

through it. 'By jove, Monash,' he said,

'you have a wonderful collection here.' 'Yes,

Sir,' says I. Then the King said. 'Do you

mind if I take this?' 'Not at all, Sir, says I,

and his Majesty slipped my precious book

into his overcoat pocket and walked off.

"Some weeks later he strolled in again. 'I've

brought you back your book, Monash,' he

said, and handed it to me. The signature

of every member of the Royal family from

King George down, had been added to my

collection, with a word of good cheer from

each."

When Sir John came back from India,

where he had been representing the

Commonwealth at the Durbar at Delhi, I remarked

to him that he seemed to work harder as

he grew older.

"Yes", he said, "I'm a busy man. Sometimes

I wish I could find time to play with

my toys."

"What are your toys, General?" I asked.

"Standard roses and the piano," he

answered, "I never seem to get time to

practise now."

Not many people knew that he was quite

an accomplished musician.

Monash's Letters.

Now, good people, don't worry

about me or my advancement. For me

it counts for very little. If they

want me to command a division they

know where to find me. So far

nobody has passed over me.

McCay, Chauvel and Legge are all

my seniors. I might have had the

4th Division. Pearce cabled Birdwood

asking that either Brudenell

White or I might get it; but Birdwood

preferred to entrust it to Cox,

a Kitchener man, and an old Indian

colleague of Birdwood's.

My thoroughly successful command

or my own brigade, and my

satisfactory performance of every task set

my brigade is quite good enough for

me, and I know what Cox and Godley

and Birdwood and Commander-in

Chief (Sir Archibald Murray)

think of me and my brigade.

AUSTRALIA'S ABLEST SOLDIER;

Brudenell White, brigadier-general,

was Director of Military Operations

in Australia. He was Bridges's

right-hand man. He was the general staff

officer, first grade, of Bridges's

division. Later on he was chief of the

general staff of Birdwood's Army

Corps. He is far and away the ablest

soldier Australia has every turned out.

He is also a charming good fellow.

Since last writing, the only two

things of interest that have

happened are, firstly, the successful raid

by a portion of our front line here

on an advanced Turkish post, in

which we captured 33 Turks and one

Austrian officer, with the loss of only

one man, and, secondly, the visit

to Serapeum of the Commander-in-Chief

(Sir Archibald Murray).

He came along with his great

retinue of generals and staff, with

Godley and his staff, the Prince of

→his staff. I put up a star turn with

all the brigade at work all over the

↑Wales, now gazetted a captain, with

desert-musketry, bayonet fighting,

grenade fighting (real grenades) and

machine-gun practice galore. The

old Commander-in-Chief was

mightily pleased, and said so.

Newspaper article - see original document

JOHN MONASH - The Boy Who Made The Man

By FELIX MEYER

THE HERALD, SATURDAY EVENING, OCTOBER 10, 1931

Newspaper article - see original document

Fence Posts and High Finance

by W.M. Hughes

THE HERALD, SATURDAY EVENING, OCTOBER 10, 1931

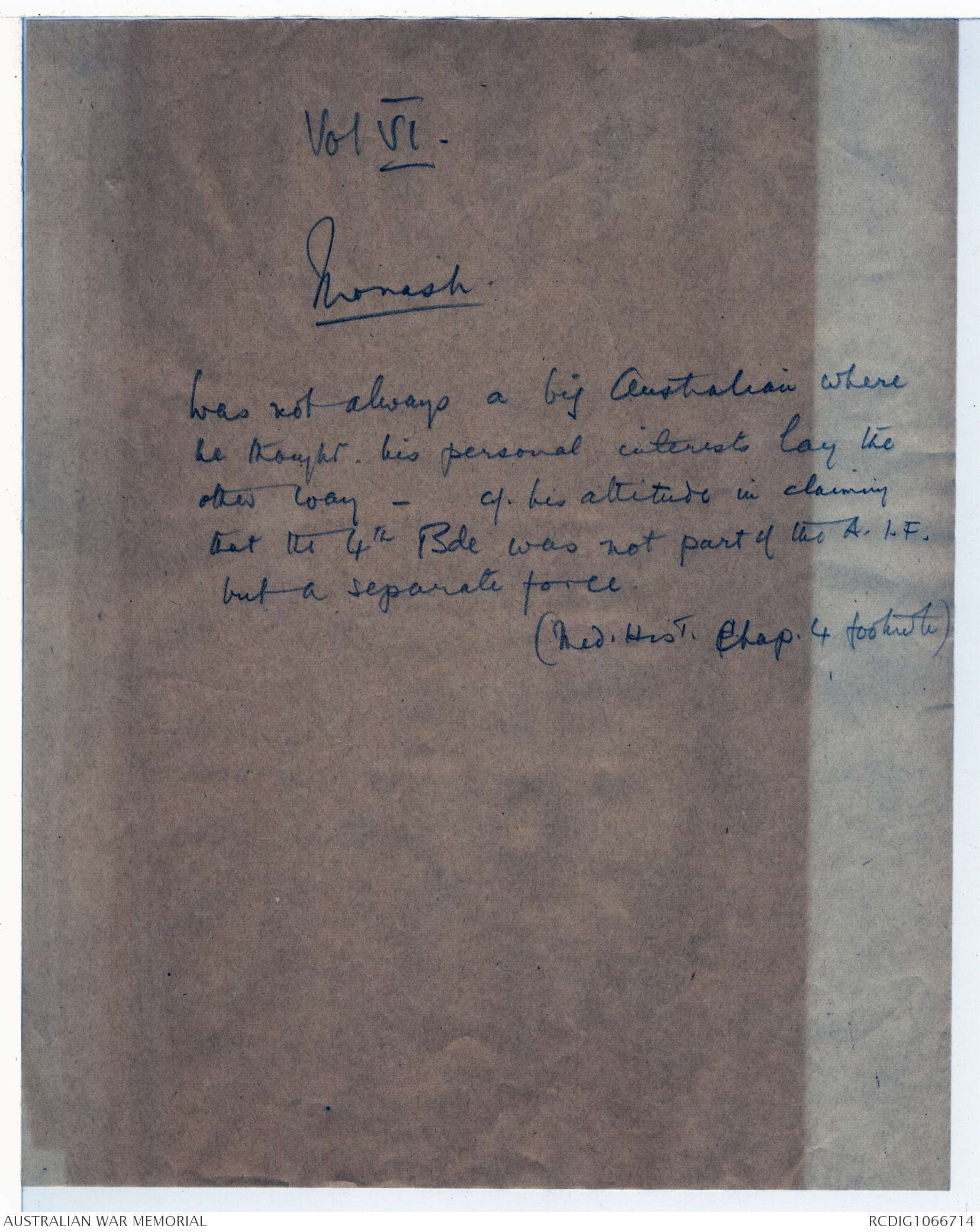

Vol VI.

Monash.

Was not always a big Australian where

he thought. his peronal interests lay the

other way - c/. his attitude in claiming

that the 4th Bde was not part of the A.I.F.

but a separate force.

(Med. Hist. Chap. 4 footnote)

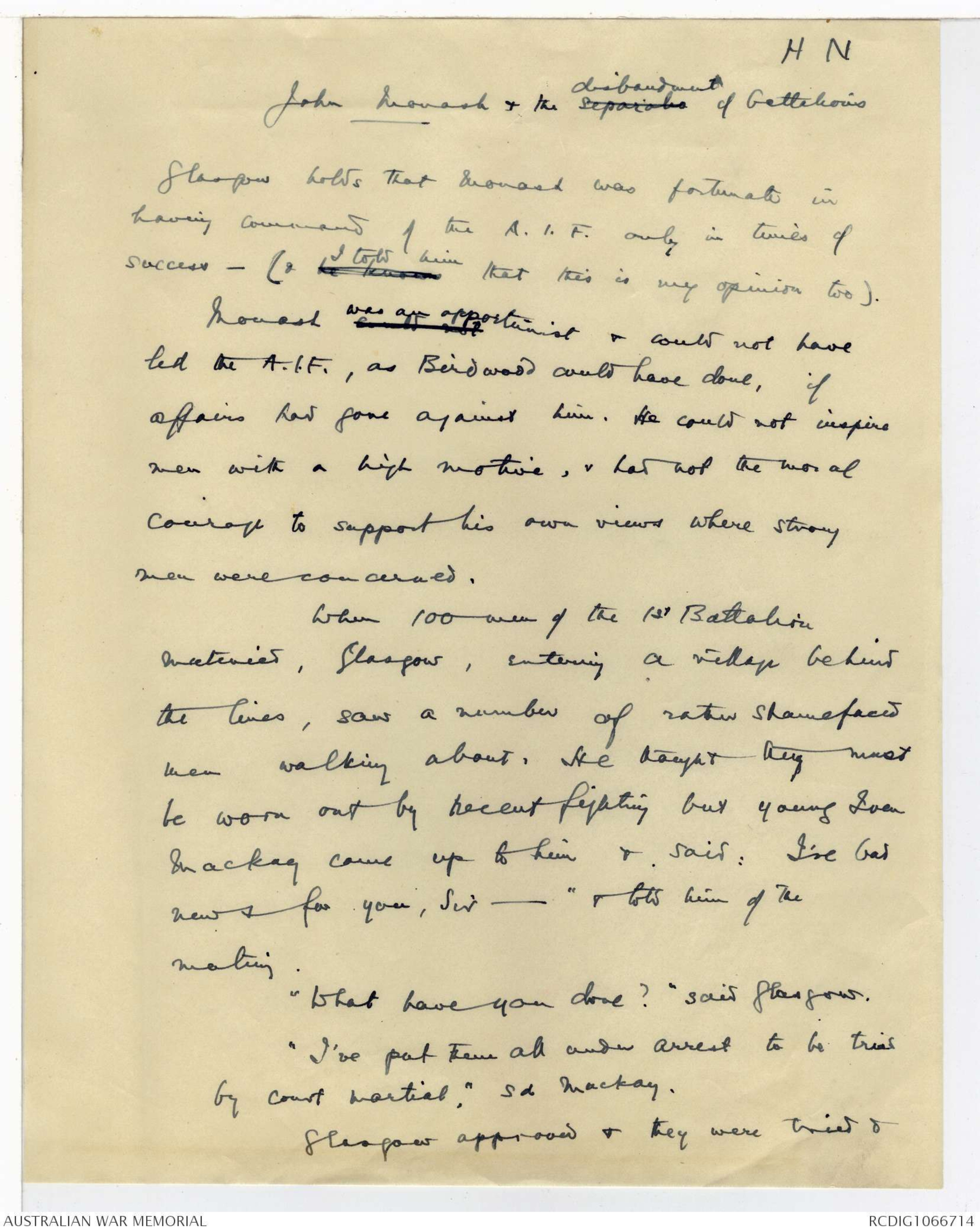

H N

John Monash & the separatio disbandment of battalions

Glasgow holds that Monash was fortunate in

having command of the A.I.F. only in times of

success - (& he knew I told him that this is my opinion too).

Monash could not was an opportunist & could not have

led the A.I.F., as Birdwood could have done, if

affairs had gone against him. He could not inspire

men with a high motive, & had not the moral

courage to support his own views where strong

men were concerned.

When 100 men of the 1st Battalion

mutinied, Glasgow, entering a village behind

the lines, saw a number of rather shamefaced

men walking about. He thought they must

be worn out by recent fighting but young Ivan

Makay came up to him & said: I've bad

news for you, Sir - " & told him of the

mutiny.

"What have you done?" said Glasgow.

"I've put them all under arrest to be tried

by court martial," sd Mackay.

Glasgow approved & they were tried &

Sam scott

Sam scottThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.