Charles E W Bean, Diaries, AWM38 3DRL 606/274B/1 - 1918 - 1939 - Part 3

May 31, 1930. The REVEILLE 9

But General Murray, who took over the Egyptian

command in 1916, got wind of Birdwood's "ambitions,"

and promptly told London that "I cannot

spare a single man. . . . The Anzacs are the

keystone to the defence of Egypt."

As the army commanders were all so keen on

having the Diggers under their command when the

big "scrapping" was going on, it would have been

a gracious act on their part to have taken them on

"a picnic parade" into Germany after the Armistice.

—"Romani."

"Headstrong."

General Hobbs, who had not read the "Reveille"

article, but relied on incomplete quotations from it

in the daily press, has not quite grasped the point

at issue.

For instance, the correspondent who first raised

the question, and on whose behalf it was referred to

Mr Hughes (war time Prime Minister) for answer,

had never expressed disappointment that the Australian

troops were not drafted

to Germany. He simply asked

if there was any particular reason

why the Australian troops

were not sent, and his reference

to Australian troops naturally

referred to the divisions,

because it was well known that

a section of the Australian Flying

Corps had crossed into Germany.

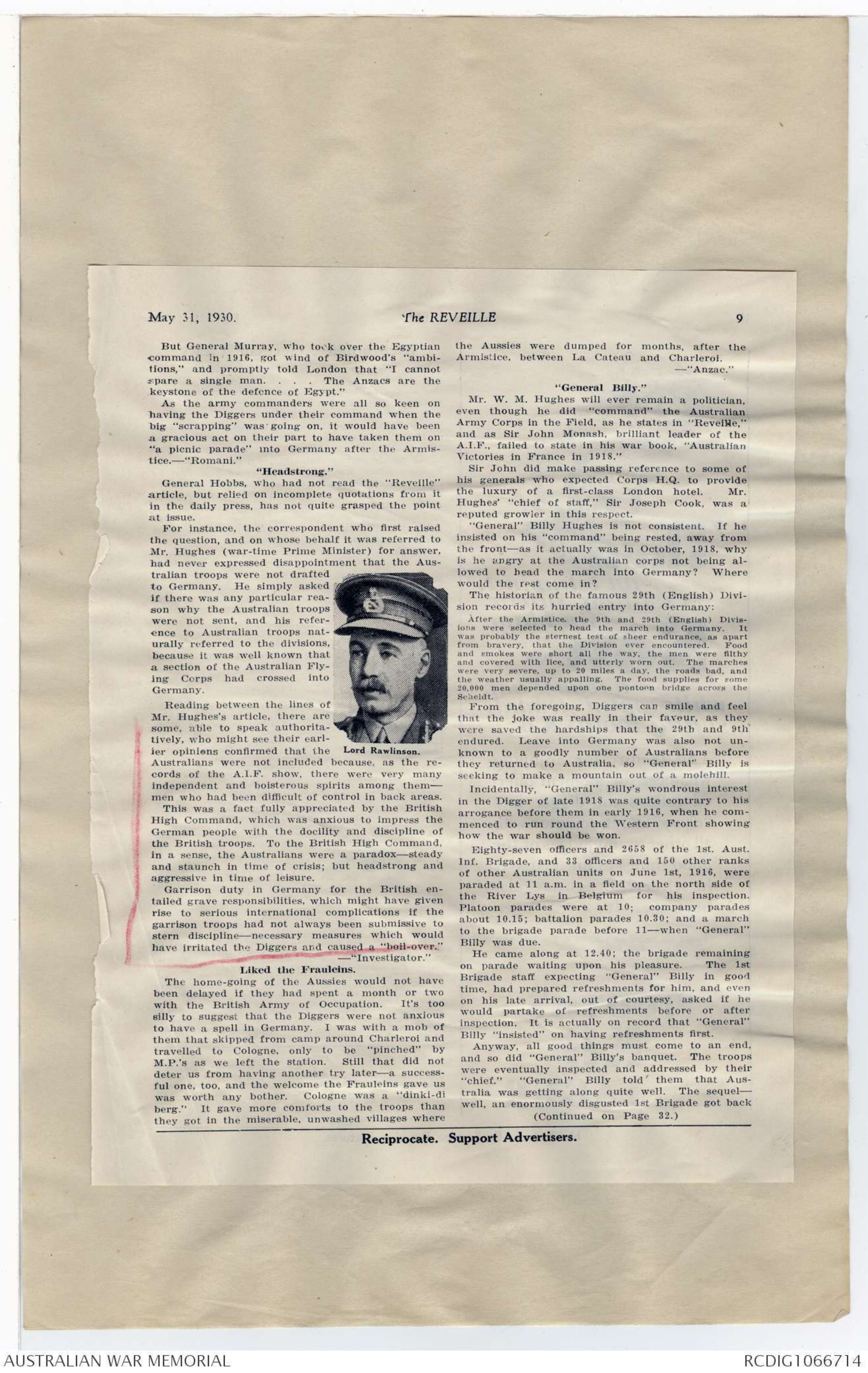

Reading between the lines of

Mr Hughes's article, there are

some, able to speak authoritatively,

who might see their earlier

opinions confirmed that the

Australians were not included because, as the records

of the A.I.F. show, there were very many

independent and boisterous spirits among them—

men who had been difficult of control in back areas.

This was a fact fully appreciated by the British

High Command, which was anxious to impress the

German people with the docility and discipline of

the British troops. To the British High Command,

in a sense, the Australians were a paradox—steady

and staunch in time of crisis; but headstrong and

aggressive in time of leisure.

Garrison duty in Germany for the British entailed

grave responsibilities, which might have given

rise to serious international complications if the

garrison troops had not always been submissive to

stern discipline—necessary measures which would

have irritated the Diggers and caused a "boil over."

—"Investigator"

Liked the Frauleins.

The home-going of the Aussies would not have

been delayed if they had spent a month or two

with the British Army of Occupation. It's too

silly to suggest that the Diggers were not anxious

to have a spell in Germany. I was with a mob of

them that skipped from camp around Charleroi and

travelled to Cologne, only to be "pinched" by

M.P.'s as we left the station. Still that did not

deter us from having another try later—a successful

one, too, and the welcome the Frauleins gave us

was worth any bother. Cologne was a "dinki-di berg".

It gave more comforts to the troops than

they got in the miserable, unwashed villages where

the Aussies were dumped for months, after the

Armistice, between La Cateau and Charleroi.

—"Anzac"

"General Billy"

Mr W. M. Hughes will ever remain a politician,

even though he did "command" the Australian

Army Corps in the Field, as he states in "Reveille,"

and as Sir John Monash, brilliant leader of the

A.I.F., failed to state in his war book, "Australian

Victories in France in 1918."

Sir John did make passing reference to some of

his generals who expected Corps H.Q. to provide

the luxury of a first-class London Hotel. Mr.

Hughes' "chief of staff," Sir Joseph Cook, was a

reputed growler in this respect.

"General" Billy Hughes is not consistent. If he

insisted on his "command" being rested, away from

the front—as it actually was in October, 1918, why

is he angry at the Australian corps not being allowed

to head the march into Germany? Where

would the rest come in?

The historian of the famous 29th (English) Division

records its hurried entry into Germany:

After the Armistice, the 9th and 29th (English) Divisions

were selected to head the march into Germany. It

was probably the sternest test of sheer endurance, as apart

from bravery, that the Division ever encountered. Food

and smokes were short all the way, the men were filthy

and covered with lice, and utterly worn out. The marches

were very severe, up to 20 miles a day, the roads bad, and

the weather usually appalling. The food supplies for some

20,000 men depended upon one pontoon bridge across the

Scheldt.

From the foregoing, Diggers can smile and feel

that the joke was really in their favour, as they

were saved the hardships that the 29th and 9th

endured. Leave into Germany was also not unknown

to a goodly number of Australians before

they returned to Australia, so "General" Billy is

seeking to make a mountain out of a molehill.

Incidentally, "General" Billy's wondrous interest

in the Digger of late 1918 was quite contrary to his

arrogance before them in early 1916, when he commenced

to run round the Western Front showing

how the war should be won.

Eighty-seven officers and 2658 of the 1st Aust.

Inf. Brigade, and 33 officers and 150 other ranks

of other Australian units on June 1st, 1916, were

paraded at 11 a.m. in a field on the north side of

the River Lys in Belgium for his inspection.

Platoon parades were at 10; company parades

about 10.15; battalion parades 10.30; and a march

to the brigade parade before 11—when "General"

Billy was due.

He came along at 12.40; the brigade remaining

on parade waiting upon his pleasure. The 1st

Brigade staff expecting "General" Billy in good

time, had prepared refreshments for him, and even

on his late arrival, out of courtesy, asked if he

would partake of refreshments before or after

inspection. It is actually on record that "General"

Billy "insisted" on having refreshments first.

Anyway, all good things must come to an end,

and so did "General" Billy's banquet. The troops

were eventually inspected and addressed by their

"chief." "General" Billy told them that Australia

was getting along quite well. The sequel—

well, an enormously disgusted 1st Brigade got back

(Continued on Page 32.)

Reciprocate. Support Advertisers.

32 The REVEILLE May 31, 1930

"AUSSIES BARRED."—Continued from Page 9.

to billets and lunch at 2.30 p.m. having spent four

and a half hours upon the pleasure of Mr Hughes.

So even if the self same warrior-statesman does

take credit unto himself for having got the Anzacs

leave and the Australian Corps a rest in spite of

General Monash's wishes that it fight on—let him

debit a little of such credit against that needless

and thoughtless action of his in 1916, when he unreasonably

inconvenienced the famous 1st Australian

Brigade — something Fritz was never allowed

to do with impunity.—Fred W. Taylor,

2nd Bn. (A.I.F.)

Race Towards Berlin

A cobber of mine, an original member of the

10th Battalion, voluntarily relinquished his right to

leave France with the 1914 furlough men for the

reason that he had come away from Aussie with

the determination to see Berlin, and did not intend

to retire just at the time the Germans were leading

the Diggers a great race towards Berlin.—"3rd

Bde." (Broken Hill).

"Often Wrong."

In the last month's "Reveille" Mr Hughes writes

on the subject of the Army of Occupation in Germany,

that "when the victory was won, and

soldiering became a holiday, the Australians were

contemptuously ignored. . . . Among the Allied

troops sent to Germany the Australians were not

included."

Mr Hughes is often wrong when he comes to

discuss the war in detail. Having heard him a number

of times, I doubt whether even yet he can

distinguish one battle at Villers Bret. from another.

Someone else may be able to say definitely

whether it was Mr. Hughes who decided that the

Australian Corps should "go into decent winter

quarters," and that this was decided in June, 1918.

But the A.I.F. was represented in the limited number

of troops selected for the British contingent of

the Allied Army of Occupation. The British and

Belgian area was Cologne and Dusseldorf, and the

4th Squadron of the Australian Flying Corps was

sent to Cologne to represent the A.I.F. Major Ellis,

their O.C., could probably write you some interesting

stories of their stay there.—"K."

Canadian View.

Mr W. M. Hughes' article makes one wonder if

all ranks were so very annoyed at having been sent

home instead to Germany. Notions of what constituted

honour and dignity differed considerably

according to one's nearness to or distance from

the front line. Any "buck" private believed that he

would be kept in France indefinitely if it was for

the sake of allowing the Brass Hats "to lead him

into a conquered enemy country." The Canadians

were not at all keen about going on into Germany—

in fact, many considered the Australians had put

one over us by getting out of it.

The Third Canadian Division captured Mons on

the morning of the Armistice, and the town was

filled with troops when the glorious moment arrived.

Every available means of celebration was

fully utilised, and all oratory bristled with the

slogan "Home for Christmas." Days passed however,

and it was learned that the First and Second

Divisions were moving up behind the Germans

and were going into occupation. The Third and

Fourth Divisions were to relieve them in January.

This caused a great deal of unfavourable comment,

and "Brass-Hatdom" received much more than the

usual amount of abuse. Then it was learned that

the Australians were not to be in the Army of Occupation,

and this caused a fresh outbreak, everybody

demanding to know why the Aussies were

being "favoured." Cook-houses and other rumour

centres were issuing "bulletins" daily. One story

was that all available boats were to be used to take

the Aussies home first, as they had the farthest to

go. Another yarn was that Canada and Australia

were to provide an Army of Occupation between

them; Canada to do six months and then Australia

six months. I remember one blithe spirit suggesting

that a picked battalion of Canadians be matched

against a picked battalion of Australian; the winners

to have first use of the transports, and the

one man that would be left of the two battalions

to receive the V.C. and a life pension. Argument

waxed hot until well on in December, when we

started to move towards the coast.—H.W. Forrester

(3rd Canadian Divis. Sigs), 38 Macleay St.,

Sydney.

Address R.S.L. Hea

[*SM Herald

7/6/30*]

THE GREAT WAR.

Part of the A.I.F.

MR. HUGHES AND SIR JOHN

MONASH.

LONDON, June 5.

A remarkable tribute to Sir John Monash

is paid by the "Daily Telegraph's" military correspondent,

in a long reference to Sir John's

statement regarding the attitude of the former

Prime Minister (Mr. W. M. Hughes). He said it

was no surprise to those who peeped behind

the veil covering the autumn of 1918. Sir John

Monash's facts tally with those already known

regarding Mr Hughes's constant pressure to

secure relief for the Australian forces, which

began weeks before the September attack on

the Hindenburg line. One of the most amusing

inner stories of the war relates to the

attack on August 8, 1918. The secret of the

attack on the front at Amiens was so well

kept that the War Council at home knew

nothing before it had been launched and

succeeded.

During the meeting of that assembly Mr

Hughes was making a vehement speech

demanding

that the Australians be taken out

of the line when the news came that the

Australians were attacking with brilliant success

and were already far inside the German

line The recall was too late. Mr Hughes

however did not relax his demand for relief,

but happily did not prevent the Australian

line from repeating its triumph, first storming

St Quentin and then breaking the Hindenburg

line.

Mr Hughes's attitude seemed partly inspired

by internal pressure from Australia and partly

by his feeling that the Australians were called

upon to do more than the troops of the mother

country Certainly the Australians played

the star role more often than any formation

In 1918 although Mr Hughes's demand began

before the chief run of success commenced.

It should be remembered that the Australians

had not, like the others, borne the

brunt of the German hammer-blows earlier

though they came up each time to help in

bringing the Germans' advance to a standstill,

and one might question whether the majority

of the Australians would have wished to avoid

the vital role thus given. Perhaps the great

part played by Sir John Monash in 1918 was

never fully appreciated. A civilian himself,

perhaps the ablest of all the commanders on

the Western Front, the war ended before he

had a chance to reveal his full scope, but

he had done enough to bring him his high

honour among the citizen forces of the

Empire.

The latest revelations show the pressure

from the rear which he had to withstand,

In standing by the troops of the Motherland

and the dominions.

[*Sydney Daily Guardian 9/6/30*]

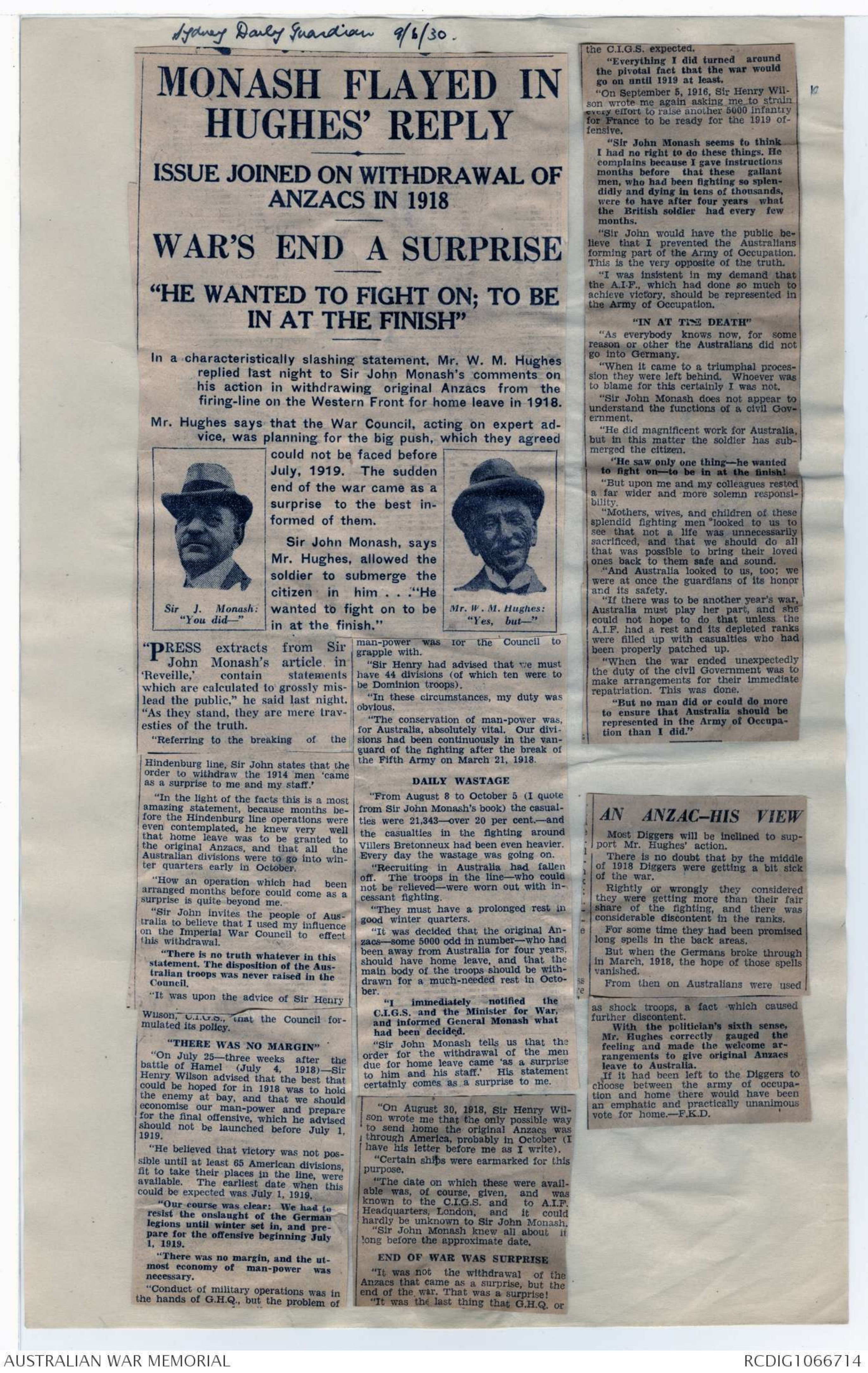

MONASH FLAYED IN

HUGHES' REPLY

ISSUE JOINED ON WITHDRAWAL OF

ANZACS IN 1918

WAR'S END A SURPRISE

"HE WANTED TO FIGHT ON; TO BE

IN AT THE FINISH"

In a characteristically slashing statement, Mr. W. M. Hughes

replied last night to Sir John Monash's comments on

his action in withdrawing original Anzacs from the

firing-line on the Western Front for home leave in 1918.

Mr. Hughes says that the War Council, acting on expert advice,

was planning for the big push, which they agreed

could not be faced before

July, 1919. The sudden

end of the war came as a

surprise to the best informed

of them.

Sir John Monash, says

Mr. Hughes, allowed the

soldier to submerge the

citizen in him . . ."He

wanted to fight on to be

in at the finish."

"PRESS extracts from Sir

John Monash's article in

'Reveille,' contain statements

which are calculated to grossly mislead

the public," he said last night.

"As they stand, they are mere travesties

of the truth.

"Referring to the breaking of the

Hindenburg line, Sir John states that the

order to withdraw the 1914 men 'came

as a surprise to me and my staff.'

"In the light of the facts this is a most

amazing statement, because months before

the Hindenburg line operations were

even contemplated, he knew very well

that home leave was to be granted to

the original Anzacs, and that all the

Australian divisions were to go into winter

quarters early in October.

"How an operation which had been

arranged months before could come as a

surprise is quite beyond me.

"Sir John invites the people of Australia

to believe that I used my influence

on the Imperial War Council to effect

this withdrawal.

"There is no truth whatever in this

statement. The disposition of the Australian

troops was never raised in the

Council.

"It was upon the advice of Sir Henry

Wilson C.I.G.S., that the Council formulated

its policy.

"THERE WAS NO MARGIN"

"On July 25—three weeks after the

battle of Hamel (July 4, 1918)—Sir

Henry Wilson advised that the best that

could be hoped for in 1918 was to hold

the enemy at bay, and that we should

economise our man-power and prepare

for the final offensive, which he advised

should not be launched before July 1,

1919.

"He believed that victory was not possible

until at least 65 American divisions,

fit to take their places in the line, were

available. The earliest date when this

could be expected was July 1, 1919,

"Our course was clear: We had to

resist the onslaught of the German

legions until winter set in, and prepare

for the offensive beginning July

1, 1919.

"There was no margin, and the utmost

economy of man-power was

necessary.

"Conduct of military operations was in

the hands of G.H.Q., but the problem of

man-power was for the Council to

grapple with.

"Sir Henry had advised that we must

have 44 divisions (of which ten were to

be Dominion troops).

"In these circumstances, my duty was

obvious.

"The conservation of man-power was,

for Australia, absolutely vital. Our divisions

had been continuously in the vanguard

of the fighting after the break

of the Fifth Army on March 21, 1918.

DAILY WASTAGE

"From August 8 to October 5 (I quote

from Sir John Monash's book) the casualties

were 21,343—over 20 per cent.—and

the casualties in the fighting around

Villers Bretonneux had been even heavier.

Every day the wastage was going on.

"Recruiting in Australia had fallen

off. The troops in the line—who could

not be relieved—were worn out with incessant

fighting.

"They must have a prolonged rest in

good winter quarters.

"It was decided that the original Anzacs

—some 5000 odd in number—who had

been away from Australia for four years,

should have home leave, and that the

main body of the troops should be withdrawn

for a much-needed rest in October.

"I immediately notified the C.I.G.S.

and the Minister for War,

and informed General Monash what

had been decided.

"Sir John Monash tells us that the

order for the withdrawal of the men

due for home leave came 'as a surprise

to him and his staff.' His statement

certainly comes as a surprise to me.

"On August 30, 1918, Sir Henry Wilson

wrote me that the only possible way

to send home the original Anzacs was

through America, probably in October (I

have his letter before me as I write).

"Certain ships were earmarked for this purpose.

"The date on which these were available

was, of course, given, and was known to the C.I.G.S. and A.I.F.

Headquarters, London, and it could

hardly be unknown to Sir John Monash.

"Sir John Monash knew all about it

long before the approximate date.

END OF WAR WAS SURPRISE

"It was not the withdrawal of the

Anzacs that came as a surprise, but the end of the war. That was a surprise!

"it was the last thing that G.H.Q or

the C.I.G.S. expected.

"Everything I did turned around

the pivotal fact that the war would

go on until 1919 at least.

"On September 5, 1916, Sir Henry Wilson

wrote me again asking me to strain

every effort to raise another 5000 infantry

for France to be ready for the 1919

offensive.

"Sir John Monash seems to think

I had no right to do these things. He

complains because I gave instructions

months before that these gallant

men, who had been fighting so splendidly

and dying in tens of thousands,

were to have after four years what

the British soldier had every few

months.

"Sir John would have the public believe

that I prevented the Australians

forming part of the Army of Occupation.

This is the very opposite of the truth.

"I was insistent in my demand that

the A.I.F., which had done so much to

achieve victory, should be represented in

the Army of Occupation.

"IN AT THE DEATH"

"As everybody knows now, for some

reason or other the Australians did not

go into Germany.

"When it came to a triumphal procession

they were left behind. Whoever was

to blame for this certainly I was not.

"Sir John Monash does not appear to

understand the functions of a civil

Government.

"He did magnificent work for Australia,

but in this matter the soldier has submerged

the citizen.

"He saw only one thing—he wanted

to fight on—to be in at the finish!

"But upon me and my colleagues rested

a far wider and more solemn responsibility.

"Mothers, wives, and children of these

splendid fighting men looked to us to

see that not a life was unnecessarily

sacrificed, and that we should do all

that was possible to bring their loved

ones back to them safe and sound.

And Australia looked to us, too; we

were at once the guardians of its honor

and its safety.

"If there was to be another year's war,

Australia must play her part, and she

could not hope to do that unless the

A.I.F. had a rest and its depleted ranks

were filled up with casualties who

had been properly patched up.

"When the war ended unexpectedly

the duty of the civil Government was to

make arrangements for their immediate

repatriation. This was done.

"But no man did or could do more

to ensure that Australia should be

represented in the Army of Occupation

than I did."

AN ANZAC—HIS VIEW

Most Diggers will be inclined to support

Mr. Hughes' action.

There is no doubt that by the middle

of 1918 Diggers were getting a bit sick

of the war.

Rightly or wrongly they considered

they were getting more than their fair

share of the fighting, and there was

considerable discontent in the ranks.

For some time they had been promised

long spells in the back areas.

But when the Germans broke through

in March, 1918, the hope of those spells

vanished.

From then on Australians were used

as shock troops, a fact which caused

further discontent.

With the politician's sixth sense,

Mr. Hughes correctly gauged the

feeling and made the welcome

arrangements to give original Anzacs

leave to Australia.

If it had been left to the Diggers to

choose between the army of occupation

and home there would have been

an emphatic and practically unanimous

vote for home.—F.K.D.

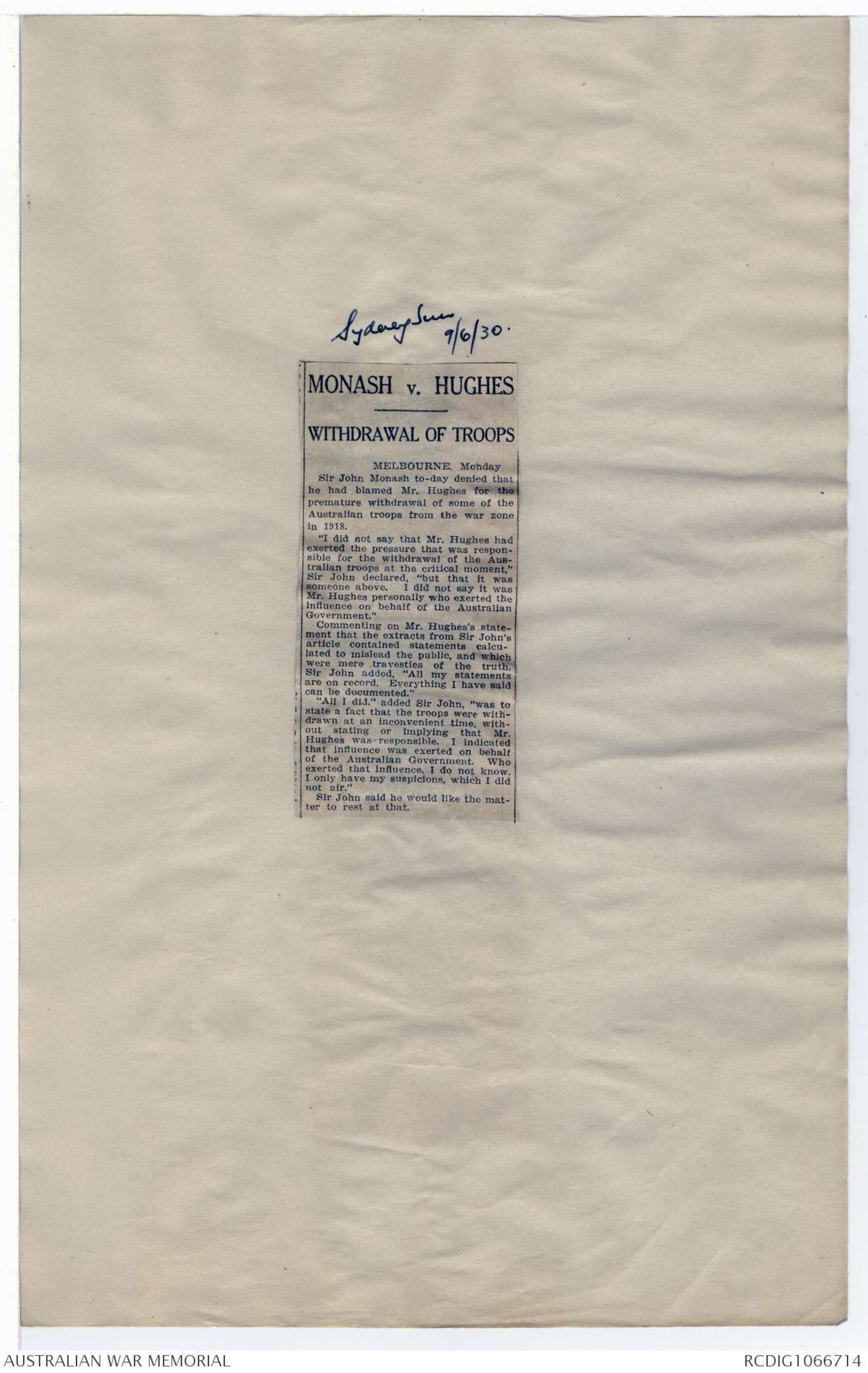

[*Sydney Sun

9/6/30.*]

MONASH v. HUGHES

WITHDRAWAL OF TROOPS

MELBOURNE, Monday.

Sir John Monash to-day denied that

he had blamed Mr. Hughes for the

premature withdrawal of some of the

Australian troops from the war zone

in 1918.

"I did not say that Mr. Hughes had

exerted the pressure that was responsible

for the withdrawal of the Australian

troops at the critical moment,"

Sir John declared, "but that it was

someone above. I did not say it was

Mr. Hughes personally who exerted the

influence on behalf of the Australian

Government."

Commenting on Mr. Hughes's statement

that the extracts from Sir John's

article contained statements calculated

to mislead the public, and which

were mere travesties of the truth,

Sir John added, "All my statements

are on record. Everything I have said

can be documented."

"All I did," added Sir John, "was to

state a fact that the troops were withdrawn

at an inconvenient time, without

stating or implying that Mr.

Hughes was responsible. I indicated

that influence was exerted on behalf

of the Australian Government. Who

exerted that influence, I do not know.

I only have my suspicions, which I did

not air."

Sir John said he would like the matter

to rest at that.

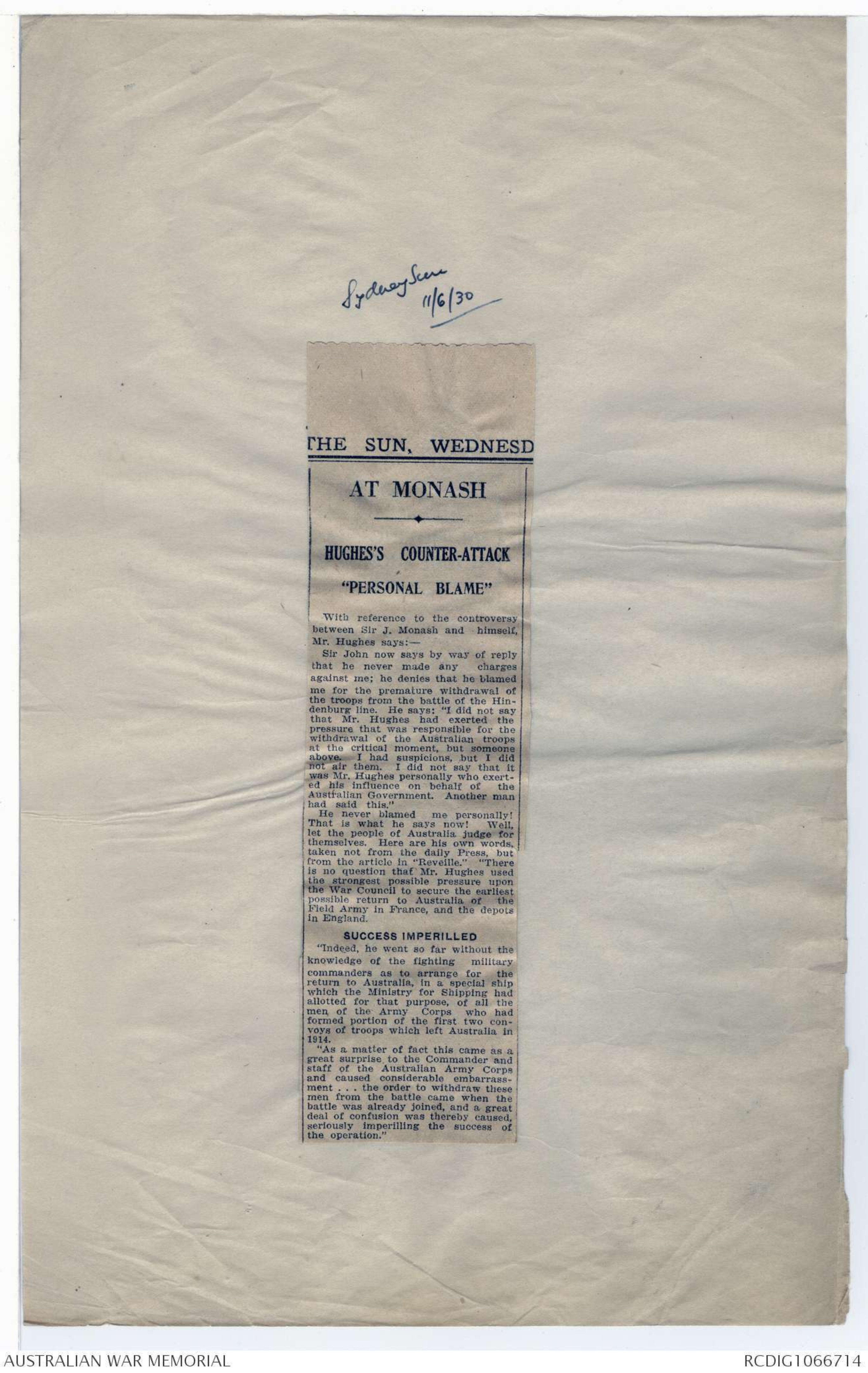

[*Sydney Sun

11/6/30*]

THE SUN, WEDNESD

AT MONASH

HUGHES'S COUNTER-ATTACK

"PERSONAL BLAME"

With reference to the controversy

between Sir J. Monash and himself,

Mr. Hughes says:—

Sir John now says by way of reply

that he never made any charges

against me; he denies that he blamed

me for the premature withdrawal of

the troops from the battle of the

Hindenburg line. He says: "I did not say

that Mr. Hughes had exerted the

pressure that was responsible for the

withdrawal of the Australian troops

at the critical moment, but someone

above. I had suspicions, but I did

not air them. I did not say that it

was Mr. Hughes personally who exerted

his influence on behalf of the

Australian Government. Another man

had said this."

He never blamed me personally!

That is what he says now! Well,

let the people of Australia judge for

themselves. Here are his own words,

taken not from the daily Press, but

from the article in "Reveille." "There

is no question that Mr. Hughes used

the strongest possible pressure upon

the War Council to secure the earliest

possible return to Australia of the

Field Army in France, and the depots

in England.

SUCCESS IMPERILLED

"Indeed, he went so far without the

knowledge of the fighting military

commanders as to arrange for the

return to Australia, in a special ship

which the Ministry for Shipping had

allotted for that purpose, of all the

men of the Army Corps who had

formed portion of the first two convoys

of troops which left Australia in

1914.

"As a matter of fact this came as a

great surprise to the Commander and

staff of the Australian Army Corps

and caused considerable embarrassment

. . . the order to withdraw these

men from the battle, came when the

battle was already joined, and a great

deal of confusion was thereby caused,

seriously imperilling the success of

the operation."

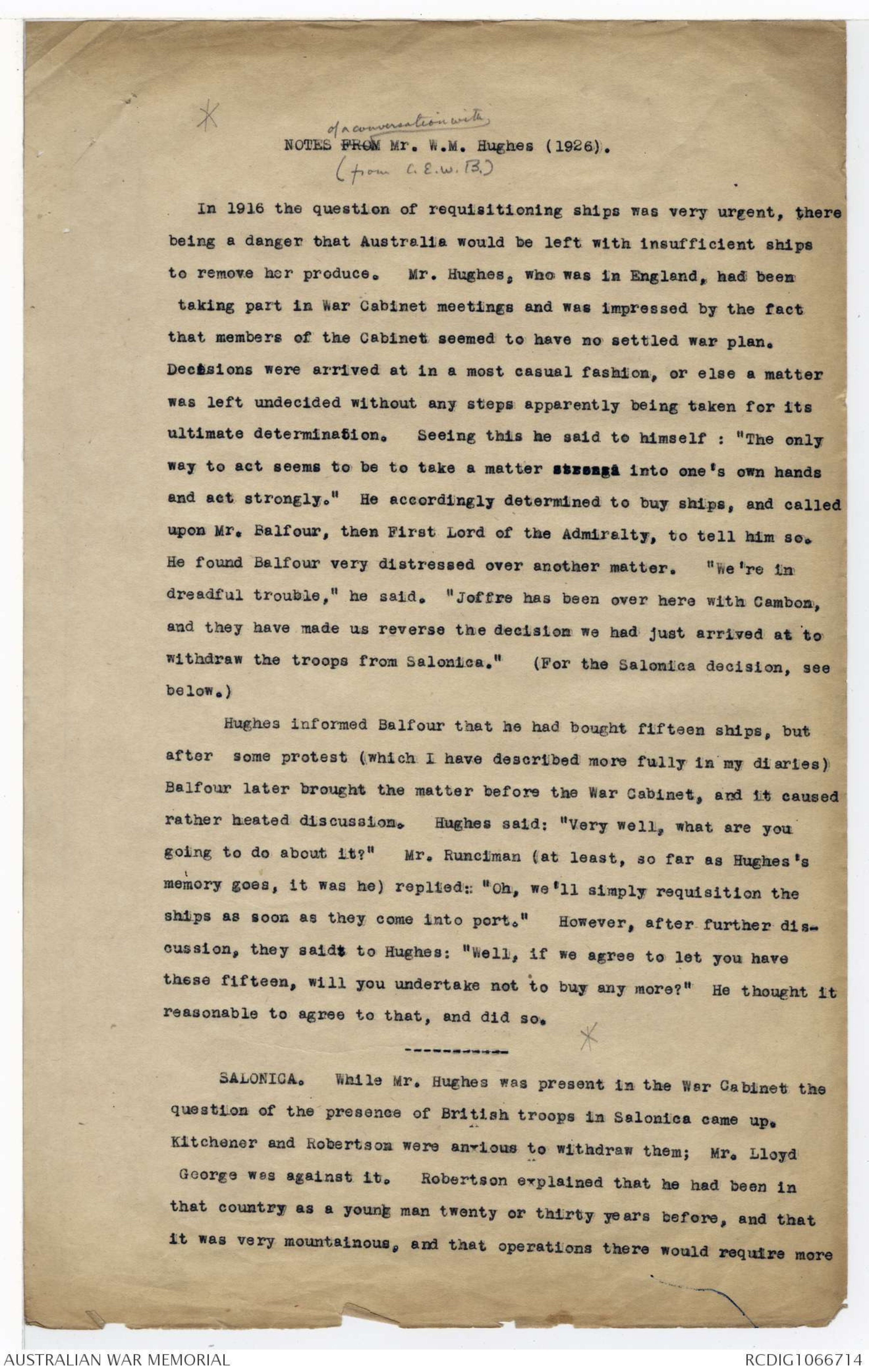

NOTES FROM ^of a conversation with Mr. W.M. Hughes (1926)

(from C.E.W.B.)

In 1916 the question of requisitioning ships was very urgent, there

being a danger that Australia would be left with insufficient ships

to remove her produce. Mr Hughes, who was in England, had been

taking part in War Cabinet meetings and was impressed by the fact

that members of the Cabinet seemed to have no settled war plan.

Decisions were arrived at in a most casual fashion, or else a matter

was left undecided without any steps apparently being taken for its

ultimate determination. Seeing this he said to himself : "The only

way to act seems to be to take a matter xxxxxxxx into one's own hands

and act strongly." He accordingly determined to buy ships, and called

upon Mr Balfour, the First Lord of the Admiralty, to tell him so.

He found Balfour very distressed over another matter. "We're in

dreadful trouble," he said. "Joffre has been over here with Cambon,

and they have made us reverse the decision we had just arrived at to

withdraw troops from Salonica." (For the Salonica decision, see

below.)

Hughes informed Balfour that he had bought fifteen ships, but

after some protest (which I have described more fully in my diaries)

Balfour later brought the matter before the War Cabinet, and it caused

rather heated discussions. Hughes said: "Very well, what are you

going to do about it?" Mr Runciman (at least, so far as Hughes's

memory goes, it was he) replied: "Oh, we'll simply requisition the

ships as soon as they come into port." However, after further

discussion, they saidx to Hughes: "Well, if we agree to let you have

these fifteen, will you undertake not to buy any more?" He thought it

reasonable to agree to that, and did so.

------------

SALONICA. While Mr Hughes was present in the War Cabinet the

question of the presence of British troops in Salonica came up.

Kitchener and Robertson were anxious to withdraw them; Mr Lloyd

George was against it. Robertson explained that he had been in

that country as a young man twenty or thirty years before, and that

it was very mountainous, and that operations there would require more

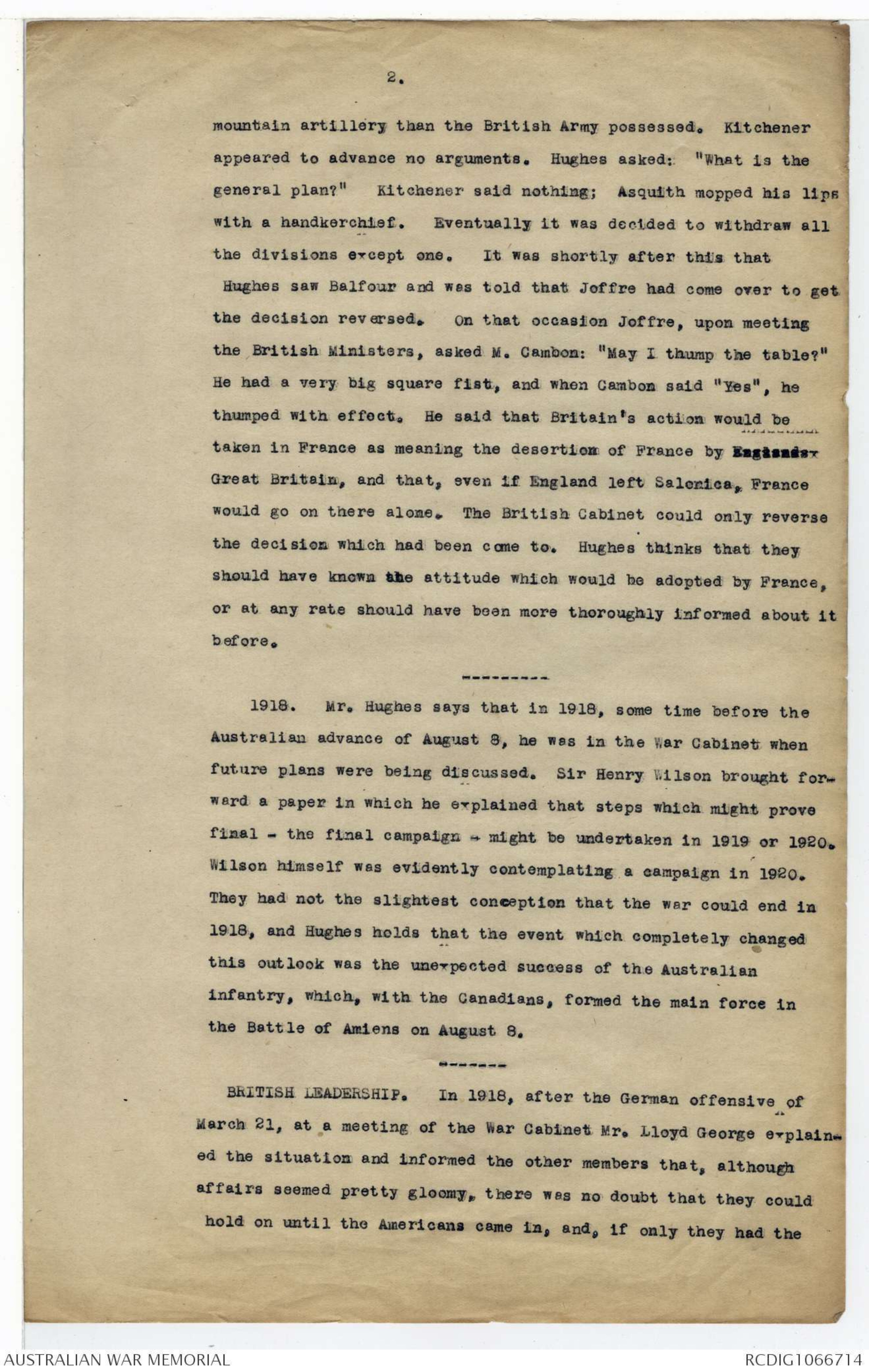

2

mountain artillery than the British Army possessed. Kitchener

appeared to advance no arguments. Hughes asked: "What is the

general plan?" Kitchener sad nothing; Asquith mopped his lips

with a handkerchief. Eventually it was decided to withdraw all

the divisions except one. It was shortly after this that

Hughes saw Balfour and was told that Joffre had come over to get

the decision reversed. On that occasion Joffre, upon meeting

the British Ministers, asked M. Cambon "May I thump the table?"

He had a very big square fist, and when Cambon said "Yes", he

thumped with effect. He said that Britain's action would be

taken in France as meaning the desertion of France by England

Great Britain, and that, even if England left Salonica, France

would go on there alone. The British Cabinet could only reverse

the decision which had been come to. Hughes thinks that they

should have known the attitude would be adopted by France,

or at any rate should have been more thoroughly informed about it

before.

---------

1918. Mr Hughes says that in 1918, some time before the

Australian advance of August 8, he was in the War Cabinet when

future plans were being discussed. Sir Henry Wilson brought

forward a paper in which he explained that steps which might prove

final - the final campaign - might be undertaken in 1919 or 1920.

Wilson himself was evidently contemplating a campaign in 1920.

They had not the slightest conception that the war could end in

1918, and Hughes holds that the event which completely changed

this outlook was the unexpected success of the Australian

infantry, which, with the Canadians, formed the main force in

the Battle of Amiens on August 8.

-------

BRITISH LEADERSHIP. In 1918, after the German offensive of

March 21, at a meeting of the War Cabinet Mr. Lloyd George explained

the situation and informed the other members that, although

affairs seemed pretty gloomy, there was no doubt that they could

hold until the Americans came in, and, if only they had the

3

courage and confidence, it was certain that they would win the war.

Mr. Borden, Prime Minister of Canada, afterwards rose and, after

speaking generally on the situation and on what Canada had done,

said that he was in possession of information which made it impossible

for him to feel confident that everything was being done for

the best, and that his obligations to the Canadian people rendered

it necessary for him to inform the War Cabinet of his misgivings.

He that Sir Archibald ARTHUR Currie, the commander of the Canadian

Corps, who was only a surveyor in private life in Canada, had

informed him that the British staff, even after three years of war,

was guilty of gross bungling. He had given Mr. Borden several

instances, which Mr. Borden proceeded to narrate to the War

Cabinet. One was the case of a British division which was employed

on the flank of the Canadians at Passchendaele in 1917. Currie

said that he, the ex-surveyor, always ensured that his troops

should be in line at least 36 hours before they were xxxxxx

to deliver an attack from it. At Passchendaele, however, a

British division came up on his flank, and its officers did not

even know where they were going or what they had to do. When the

attack took place the Canadians found themselves being fired into

from a position on their flank and rear, and, assuming that it was

German fire, they shot back. It was discovered shortly afterwards

that it was the British division that was firing upon them, and

losses had been fairly heavy on both sides. Currie further said

that the Canadians had been ordered to take Passchendaele and had

eventually done so, but that it was his opinion that the taking of

this position was entirely useless, since, as soon as it was

captured, they went on the defensive. Nearly 300,000 men had

been lost in the Ypres offensive, and this loss greatly impressed

the Cabinet as it did the British people. (Although ^as I told Mr.

Hughes, xxxx the Somme offensive in 1916 was actually a far more

bloody and less well-conducted battle, and, I think, more disastrous

to the British Army and Empire in that it practically wiped out the

first flower of Kitchener's Army and disillusioned all those

splendid men and shattered their magnificent enthusiasm.)

As another instance, Mr. Borden stated that at a conference

4

during the winter of 1917/18 corps commanders were asked how much

wire they put down in front of their lines against the event of a

German attack. A British commander, who a regular soldier should

have by this time appreciated the elementary needs of warfare, said

said that he had 30,000 yards, another 33,000. Currie had put

down 350,000.

These were cited as instances of the failure of the class

from which the British staff was drawn. Mr. Massey, to whom

everything that the British Great Britain did was right, except

where it conflicted with anything that New Zealand had done, then

gave instances of a similar nature in connection with the New

Zealand attack at Passchendaele. Hughes did not say anything, as

as he did not see for the moment what there was he could usefully say.

Lloyd George simply finished the session by saying that they

must have time seriously to consider what they had heard. After

this session Lloyd George, meeting Hughes, I think, in the passage

said to him that he wish he (Hughes) had been there in 1917. "If

you had," he added, "we should have had a different leadership now."

Hughes asked him what he meant. L.G., speaking with such sincerity

as to impress Hughes, replied that he himself was not a member of the

class with which all positions in the British Army were staffed.

If he had made any move or taken any steps to remove Haig, the cry would

at once have been raised throughout the country that politicians were

interfering with the generals. If they had stopped the Passchendaele

offensive, the generals would have turned around and said: "You

stopped us just when we would have got through. If it had not been

for you we xxxx should have broken through the enemy in that battle."

But if the action had been taken on the initiative of the Australians,

or of any other Dominion, the people would probably have accepted it.

Mr. Hughes and the other three Prime Ministers met and

consulted as to what could be done. They all felt that a change

should be made in the command of the British Army, and recognised

that Lloyd George was looking to them, if anybody, to suggest it.

However, it was clear that at the moment, when matters were

critical, such a drastic proposal coming from them, and supported,

Sam scott

Sam scottThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.