Charles E W Bean, Diaries, AWM38 3DRL 606/274A/1 - 1918 - 1941 - Part 11

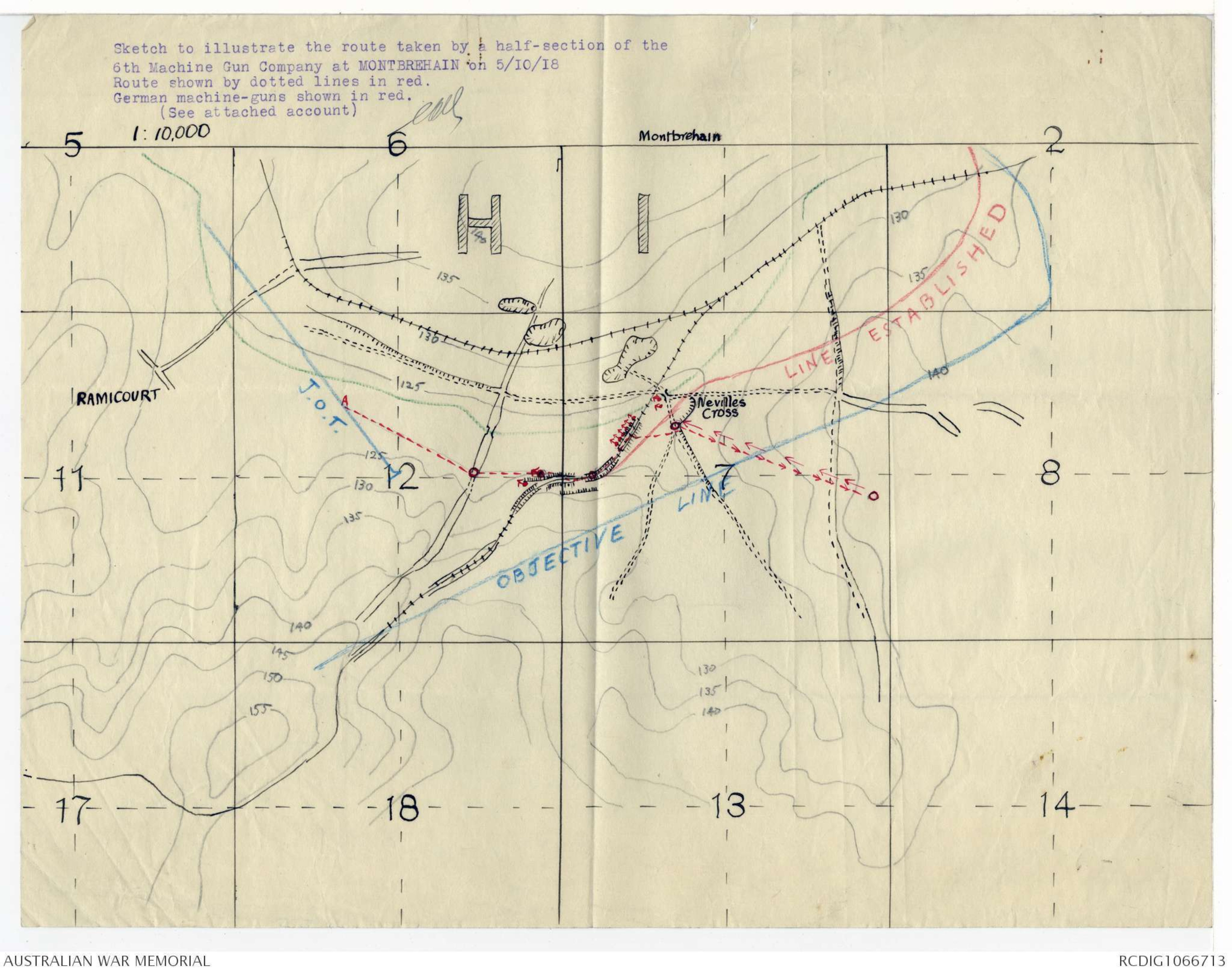

Sketch to illustrate the route taken by a half-section of the

6th Machine Gun Company at MONTBREHAIN on 5/10/18

Route shown by dotted lines in red.

German machine-guns shown in red.

(See attached account)

Map - see original document

H.N.

TELEPHONE Nos.

F2597.

F2598.

COMMUNICATIONS TO BE ADDRESSED TO

"THE DIRECTOR".

IN REPLY PLEASE QUOTE

NO. 12/3/25

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA.

TELEGRAPHIC ADDRESS

"AUSWARMUSE"

AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL.

POST OFFICE BOX 214D.

EXHIBITION BUILDINGS, MELBOURNE,

"They gave their lives. For that public gift they

received a praise which never ages and a

tomb most glorious - not so much the tomb in

which they lie, but that in which their fame

survives, to be remembered forever when occasion

comes for word or deed..."

27th March, 1929.

Dear Mr. Bazley,

I have just been looking through a

translation by I.F.D. Morrow of Rudolf Binding "A Fatalist

at War".

The book is a diary of a German officer

who apparently served near Arras, Passchendaele, and on the

Somme in 1918. I have decided therefore that we ought to

include it in the library.

It will in due course appear in our

accession list and, if you want it, you will doubtless let

me know.

Incidentally I noticed a reference on

page 164 to the association of Joan of Arc with Beaurevoir

which may be of interest to Mr. Bean when he comes to deal

with the fighting in which the Australians participated in

the neighbourhood of this town.

Yours sincerely,

[[JRNelson?]]

Mr. A. W. Bazley,

C/o. Official Historian,

Victoria Barracks,

Paddington.

N.S.W.

MACROSSAN & AMIET

SOLICITORS

WM. A. AMIET, M.A.

BARRISTER-AT-LAW

J. S. AMIET, B.A.

BARRISTER-AT-LAW

Telephone No 51

P.O. Box 76

Mackay, 3rd April 1937.

NORTH QUEENSLAND

Captain C.E.W.Bean (Official Historian),

c/o Messrs. Angus & Robertson,

Castlereagh Street,

SYDNEY N.S.W.

Dear Sir,

I enclose herewith my account of the operations performed

on 3rd October 1918 by my battalion (the 26th), of which I was

intelligence officer. The account may be of no assistance to you; on

the other hand it is possible that it may provide connecting links of a

useful nature. There will be no need to acknowledge it, and my only

reason for offering it is that microscopic specks of truth are obviously

one of your major considerations, and it is out of these specks that you

have erected our five most magnificent national volumes.

Yours faithfully,

WA Amiet

Enclos.

Acknowledged

BEAUREVOIR

It was on the 20th September 1918 - the anniversary of Polygon

Wood - that news of the anticipated stunt reached the battalion. But how

differently the morning broke. Then it had been chilly and wintry, with

sharp driving rain pelting upon us as we lay in open pot-holes awaiting

the roar of the guns. Now, according to my diary, it was a "glorious

day - one storm". Moreover, for the interminable waste of shell-ploughed

desert, with which the dawn of day had greeted our eyes a year before,

there was were substituted the trees and meadows of the lazy Somme canal. The

camp was at ExEclusier, with its little desecrated church overlooking the

water. The troops were resting, and dolce was the far niente. xxx.

There were some who thought that our fighting days were over until

Christmas. All sorts of rumours were afloat about the wonderful holiday

the division was about to commence - a holiday which even then it seemed

might possibly outlast the war. But the news of yet another stunt brought

no discontent. "Great glee everywhere", is my observation then recorded.

We did not let the disclosure unduly interfere with our diversion. The

next few days were cool and pleasant, with occasional storms to clear the

atmosphere. We went on route marches, mounted guard, conducted courts

martial, entertained our friends from the neiug^hbouring units and took long

walks in what a captured home-letter described as "das berühmte Sommetal".

On the 23rd the Major and I strolled as far as the Chateau of the Marquiset d' Etourmel at Cappy, admired the great rooms, grand even in their wreckage,

deciphered the cuarved mottoes, stood with some reverence in the family

chapel - the only apartment which friend and foe alike had left intact,

and inspected the family graves in the courtyard some of which bore dates

as far back as 1590. That night there fell upon our ears the sound of a

furious bombardment in the east, and the very next morning we began to

practise for the serious affair which every day brought closer. We staged

a full dress rehearsal, with runners and observers, over the country to the

village of Maricourt, and on the following day marched via Fontaine-les-

Cappy with its smashed-up sugar factory on to the long straight Amiens

road, left-wheeling to Hereville Herleville to witness a demonstration of tanks - a

male and two females, and I returned via Chuignes with its mammouth Paris-

bombarder to attend a meeting of Second-division intelligence officers at

Cappy. The only untoward event in progress was the strike of the 19th,

21st and 25th battalions against their disintegration - undisciplined

2

perhaps, but embodying a type of indiscipline which brought a fierce kind

of pride into the hearts even of those whose duty it was to repress the

rebellion.

Farewell to Eclusier. An early swim in the canal, the business

of packing up, last letters home, a beautiful day, a crisp night! At 7.15

p.m. on the 27th we left, not without regret, our happy and comfortable

tents and set our faces once more towards Berlin. As we tramped along

through Herbecourt there occurred one of the most magnificent searchlight

displays I have ever seen. Clearly all was not well in the upper air.

Crossing the Somme at Halle we marched in silence through the dead and

silent city of Peronne, the moonlight gleaming on its desolate walls. By

one o'clock in the morning we were safe in our appointed Nissen huts at

Doingt, where we slept till nine.

The two snoring forms on either side of me were the Padre and

the Doctor. When, thought I, shall I sleep in such physical and spiritual

calm again? Outside the rain was streaming down. We shaved and breakfasted

in bed, no less, and then got about our respective jobs. Mine was to

go to Brigade and get the maps for the stunt, and issue them to the proper

persons. I still have mine - the One-in-20,O00 Wiancourt" - yellow with

age, and Hindenburg grime. The German trenches, marked in blue, were

alleged to have been "corrected from information received up to 19.9.18" -

nine days previously. There was a meeting of officers, and at 7 p.m. we

set out over a sloppy road via Bussu for Templeux-la-Fosse, where we xxxx

settled down to a freesing night in billets.

On the 29th, our third and fifth divisions, with the Yanks,

hopped over, so we were told. We worked all day on the maps, and in the

evening the Padre and I took a walk to the old ruined church in the village

and its mossy graveyard, where the family vaults had been used as dugouts,

and we gazed with some not without wonder at a memorial erected over the burial place

of "41 englische Soldaten", with its chivalrous inscription: "Sie

starben den Heldentod, 21.3.18". Were these the enemies concerning whom,

six months earlier at our Oxford O.C.B., they had been enlightening us in

special lectures entitled "Hate." "There is no good Hun but a dead Hun",

was the lecturer's slogan. "You must hate! hate! hate!" I referred the

matter to the Padre, but he remained silent. Then back to the Nissen huts

to a stirring game of poker, while a wild rainstorm rattled on the tin

roofs.

The last day of September found us still cooling our heels

3

impatiently in the huts. The troops were spoiling for action. This lull

in the proceedings was neither fish nor fowl. That day the galvanic

reports were circulated that Bulgaria had surrendered, that the cavalary

was marching south on Lille, and that Bellicourt ahead of us had fallen.

We began to wonder whether the Wiancourt maps would be much use after all.

Perhaps something closer to Alsace-Lorraine would fill the bill better.

The suspense was not of long duration. Next morning the

battalion moved eastward by way of Tincourt with its comparatively sound

buildings and Roisel where not an undamaged house remained. Posted up in

Roisel was a notice on the battered billets in German explaining that bells

denoted an air attack, drums a fire alarm. ^The village seemed to have had a fair share of both. We rested during the afternoon

in bivvies beside four dead horses in Hankey Quarries, just through

Templeux le-Guérard. There we were treated to a most daring raid by a

German airman, who in one minute destroyed two of our observation balloons

The great fat sausages melted instantaneously into flames and vanished,

and nothing but a falling black object or two broke the view.

After that they gave me a horse, one "Sugar", and on him I

reconnoitred the road, through Hargicourt and Villeret, along which the

battalion was to march that night. It was called the Black Road and

black it was by name and nature. The rain had made it boggy, and as in the

darkness we trudged along it on foot, sinking kneedeep in mud and halting

for what seemed like hours until some transport waggon or gun was dug out

ahead of us, we cursed it in our most fluent Australian. But all roads

have an ending and at some time during the night we crawled into the

support trenches occupied by the twenty-ninth, and gave them welcome

relief. This was a Geelong battalion and it was a cheering interlude to

drop into a trench filled by the fellow townsmen of one's youth, and talk

of Corio Bay and the River Barwon until the hand-over was complete.

Day dawned brightly on the second of October. It is the

intelligence officer's duty to accompany his C.O.round the sights of the

city, and so at nine o'clock the two of us set off up the slope to Nauroy

and there from an old garden, about which the sickly scent of ,mustard gas

still clung faintly, we enjoyed a magnificent view through our glasses of

the enemy villages spread out before us - Premont, Montbrehain, Joncourt

and Beaurevoir. It was a lovely, sunny morning. Everything was calm and

still. Especially still were half a dozen British tanks dotted over the

gradient. They had all been put out of action, apparently by direct hits

from close artillery. The crews were dead, and some had been trapped and

4

badly burnt. At night we both went out again and did a reconnaissance

over ^by Estrées,. Shells began to fall around and we returned to our

hospitable hole in the ground to discuss the future of Europe with our

colleagues, Lloyd the Adjutant and Dick Whittaker.

Morning came. All hands and the cook were stirring long before

dawn. That day the 26th were to have the honour and glory of serving as

the point of the spear which was to pierce the last bulwark of the impregnable

defences of the Hindenburg line. That we should succeed was never

questioned. The companies disappeared stealthily in the direction of the

jumping off points. The Colonel, a couple of runners, and myself, made

for the clump of trees shown on the map as Folemprise Farm. On this

target a distant gun was letting high explosive drop at moderate intervals.

We would hear the hiss, wait for the burst and thank heaven for the distance

between us and it. There came another; the fragments whizzed around us,

and we had begun our usual mental tribute to Divine Protection when the

quiet voice of the Colonel, who had halted, announced "I'm hit". "Here",

he said to one of the runners, indicating an arm hanging loosely by his

side, "bandage this." But his thoughts were on the objectionve and all his

plans, and the movements we had talked over yesterday almost at this very

spot. "Cooper" he said, "will have charge, so-and-so will take over A

Company. Now, take these messages", and so he went on detailing his

directions while we, listening, forgot about his wound. "But no one is

looking after my arm", he observed after a couple of minutes. So we left

a man to fix him up and on we went again.

My runners were all in their places. I went along the line of

troops waiting in quiet little groups for 6.5, told the dreary news of

the Colonel, sought out Cooper, and looked for Lloyd, the adjutant. But

he too had been hit x- windpipe nearly severed, someone said. This was a

bad start - this elimination of headquarters at the outset. But Cooper

was a cool head and knew his job, and we sent back for George Francis, the

popular assistant adjutant. Meanwhile the clock ticked on, down came the

barrage, and over we went.

Artillery formation was the method of advance. Left and right

little serpentine strings of men began to follow up the line of bursts

which in the grey morning light were chruurning up the ground ahead of us.

Soon hostile shells answered to scatter the strings, but in spite of a

goodly number of casualties there was not the slightest hesitation.

Down the slope we gravitated to the valley of the Torrens canal. Machine

5

gun fire was pouring in from a quarry on our right, and the company on the

right told us later in the day how fireercely the German machine-gunmen

had stuck to their job until the final hand-to-hand struggle put them out

of action. My own personal objective was Lormisset, a prominent farmhouse

about half a mile away on the top of the next hill, and just across the

ominous blue dots which marked the powerful line of fortifications in the

Hindenburg system designated on the map the "Beaurevoir line" In the

valley were a couple of the enemy's guns, which had been abandoned. My

function was to get information back promptly and, being anxious to justify

the Colonel's choice ^of a new intelligence officer, It it was my intention to be

first into the first trench. As I hastened up the hill in front, towards

the place where the enemy line bent northwest, there came the rumble of a

tank ascending behind me - a friendly and reassuring rumble it was. But

the effect was moral rather than material, as things turned out. I reached

the wire simultaneously with Captain Stapleton and my old friend Sergeant

Lancaster of Neuve Eglise days. "Good morning" we all said, politely, as

we commenced to cut the obstruction with our snippers. It did not take

long, and as we struggled through there came a rush of prisoners with hands

uplifted. They surrounded our little group and began offering us souvenirs

- they seemed to know the Australian point of view. As I rattled off the

prescribed questionnaire and wrote down the answers my pencil point broke,

and about seven of them pulled pencils out of their pockets and offered

them to me. The poor beggars were anxious to please. I couldn't help

noticing how they were quivering. That bombardment of ours must have

given them hell. When the questions were answered they scampered off

delightedly down the hill towards our lines, keeping their hands well up.

Then we entered the trench.

It was a fine piece of work, this arm of the Hindenburg defence.

Great concrete dugouts were built into the trenches. They seemed as rooted

to the earth as the rocks of nature, but, as we found the next morning when

sheltering in one of them from the barrage of the counter-attack, they

moved about like a ship at sea under the pressure of the bursting shells.

I came upon a sergeant who was getting a broken hand doctored up and tried

to get a bit of information out of him. But he was surly and short in his

answers, as perhaps a man with a broken hand was entitled to be.

Before investigating Lormisset, I decided to push on along the

trench line with Stapleton and his company and find the best place from

which to commence the assault on Beaurevoir. But we began to catch up to

6

our own barrage and sat down in a huge shell hole to wait. There were

about ten of us, including the company commander and one of his platoon

officers, a very decent little fellow named Carter. He and I spread out

my map on the forward parapet and were picking out objects of interest

round Beaurevoir. I asked him a question a couple of times but when I

looked up from the map to see why he was not answering, he was dead.

The next minute there came a fiendish roar as one of our own

projectiles burst fair in the middle of the shellhole. Every other form

in the shell hole lay still. Stapleton, I took it, was knocked out. As

for myself there was ^a sharp sting and a sudden rush of fluid putteewards.

I clapped my hand to the affected spot and found that the water bottle

had taken the full force of the impact and hung twisted and empty and that

no bones were broken. I raised the cry of stretcher bearers and they came

from nowhere and took charge. The rest of us in the vicinity fell back a

shell hole or two to wait for the guns to lift. Half an hour later,

Stapleton was away out in the blue once more, leading the remnants of his

company along the trench.

Meanwhile, remembering my task, I prepared my list of identifications

and sent them back by a runner. What they were I have long since

forgotten. And then we turned our thoughts to Beaurevoir with its red

and white buildings a mile or so away slightly north of east. The

company troops bacshed their way northward along the trench, but we of

headquarters commenced to stroll across the paddock on the German side of

the line. It was getting on for eleven o'clock. When I say stroll I

mean just that. The fierce bombardment had died down. No hostile heads

were showing. The morning was a perfect one. A bright sun shone through

a crisp atmosphere. Peace reigned on the battlefield - or so it seemed

after the contrasting hullabaloo just ended. Diggers dotted the sward

seeking out hostile burrows. On the distant heights ahead appeared for

a moment a line of cavalry, which quickly withdrew. "Uhland!" we told one

another.

I kept on in a northerly direction till I came out on a highway

- the Goyuy-Beaurevoir road. There I encountered Corporal Mead, a fellow

N.C.O.on the transport which had brought us to England. We had not met

since the training period on Salisbury Plains. And we have not met since.

But it was a friendly five minutes we spent on the Gouy road. Then I

turned eastward and walked along to a farm house on the same road, "Belle

Vue" by name. In the corner of an old stone wall one of our D. Company

7

officers had erected a Lewis gun, and, all alone, was putting bursts into

the village. He had been a gunner in his digger days and was having a

great time. In the farm yeard was a piece of artillery on which I duly

chalked the device "Captured by 26th battalion." One had to watch one's

prizes in those days. The keenest spirit of rivalry existed between the

units, and there was always the risk of some trespasser from the Fifth

Brigade coming over to claim it.

The farm yard was tunnelled like a rabbit warren. I shouted in

German down a couple of holes and fired my revolver hell-wards into the

cavities, but all was silent. Said Hocking (the officer-gunner): "You are

not getting enough intelligence back. Why don't you go to Brigade, and get

us a barrage and we'll take the village in no time?" So back I went across

the paddock to Mushroom Quarry and interviewed Eddy Cleary of the 25th, who

had some generallisimo type of job at headquarters that day, conveying to

him the compliments and expectations of D company. Then, some talk with

Holloway, the intelligence officer of the 7th Brigade, by whom I was entrusted

with the duty of making out a "Disposition Report". This meant a

tour of the front line, so off I limped in lonely state across the same

old paddock. For a moment stillness reigned again. It seemed that I was

alone in the world. But what is that crescendo buzzing overhead? Fritz

in the air has seen me. He has divined my mission. It must at all costs

be forestalled. And zip, zip, zip, his bullets whistle around as down he

swoops. It was then that, prompted by I know not what instinct of self-preservation,

I gave the gentleman the most realistic exhibition he had

ever seen of an Australian subaltern falling dead on the ground. Gratified

he flew away, and I do not mind admitting that I allowed a decent

interval to elapse before coming to life again and proceeding with my in

dispensable "Disposition Report".

By three in the afternoon it was complete. I had ascertained

where all the companies were and what they were doing and I took the document

importantly to Brigade Headquarters. By this time the wee bit wound

was getting very stiff. But worthy Doc. Newing, with sleeves rolled up and

perspiration streaming down his face was patching up broken humanity in t

the Quarry and he patched up me. "You'd better go out", he said, but by

this time I was getting properly warmed up to the intelligence task and

it was necessary to let our acting commander know whether or not he was

to sup that night in Beaurevoir. So back to the front line once again.

The sun's rays were sloping to the west. The poor old corpses

Sandy Mudie

Sandy MudieThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.