Charles E W Bean, Diaries, AWM38 3DRL 606/269/1 - 1918 - 1936 - Part 8

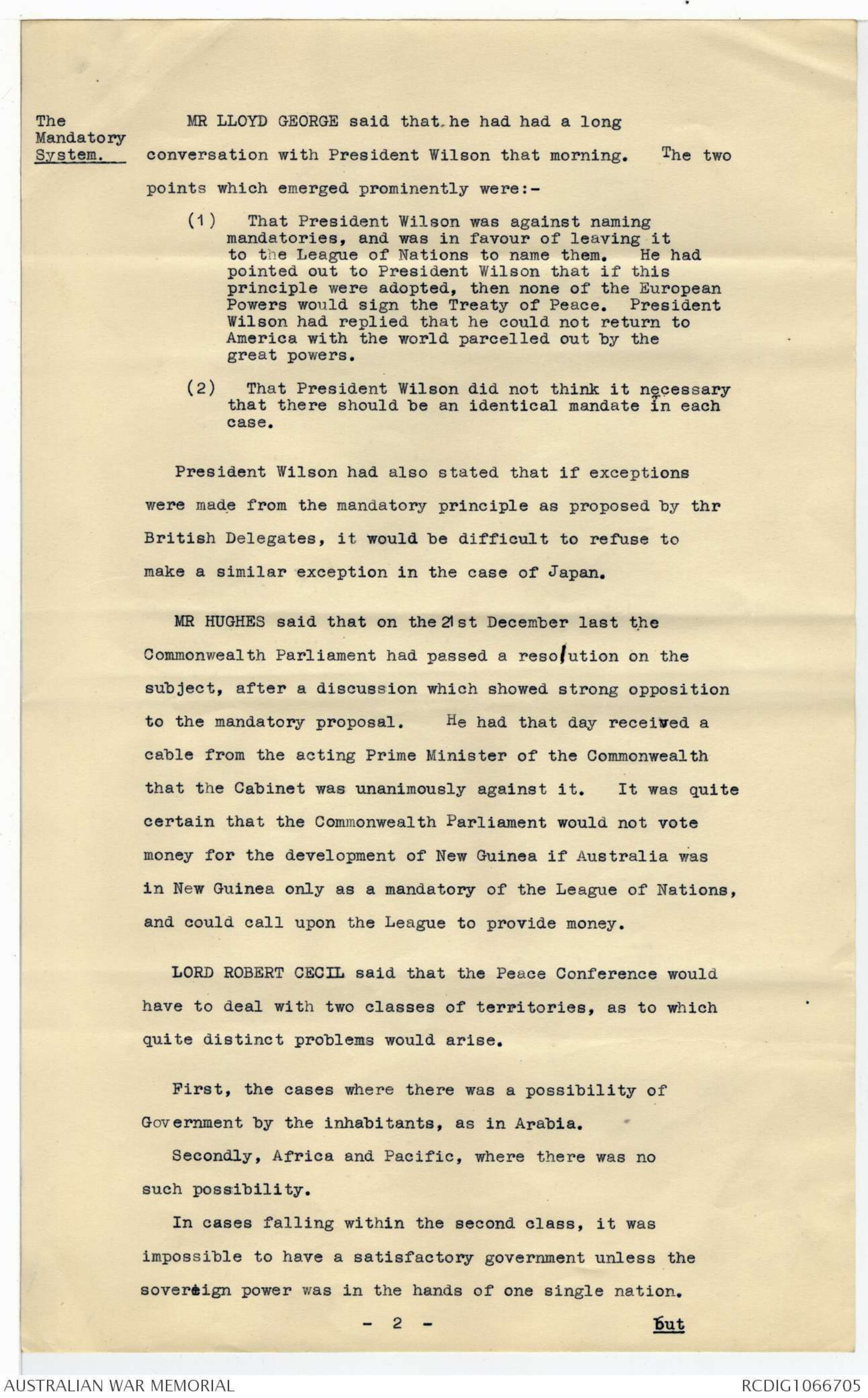

The

Mandatory

System.

MR LLOYD GEORGE said that he had had a long

conversation with President Wilson that morning. The two

points which emerged prominently were :-

(1) That President Wilson was against naming

mandatories, and was in favour of leaving it

to the League of Nations to name them. He had

pointed out to President Wilson that if this

principle were adopted, then none of the European

Powers would sign the Treaty of Peace. President

Wilson had replied that he could not return to

America with the world parcelled out by the

great powers.

(2) That President Wilson did not think it necessary

that there should be an identical mandate in each

case.

President Wilson had also stated that if exceptions

were made from the mandatory principle as proposed by thr

British Delegates, it would be difficult to refuse to

make a similar exception in the case of Japan.

MR HUGHES said that on the 21st December last the

Commonwealth Parliament had passed a resolution on the

subject, after a discussion which showed strong opposition

to the mandatory proposal. He had that day received a

cable from the acting Prime Minister of the Commonwealth

that the Cabinet was unanimously against it. It was quite

certain that the Commonwealth Parliament would not vote

money for the development of New Guinea if Australia was

in New Guinea only as a mandatory of the League of Nations,

and could call upon the League to provide money.

LORD ROBERT CECIL said that the Peace Conference would

have to deal with two classes of territories, as to which

quite distinct problems would arise.

First, the cases where there was a possibility of

Government by the inhabitants, as in Arabia.

Secondly, Africa and Pacific, where there was no

such possibility.

In cases falling within the second class, it was

impossible to have a satisfactory government unless the

sovereign power was in the hands of one single nation.

-2-

but

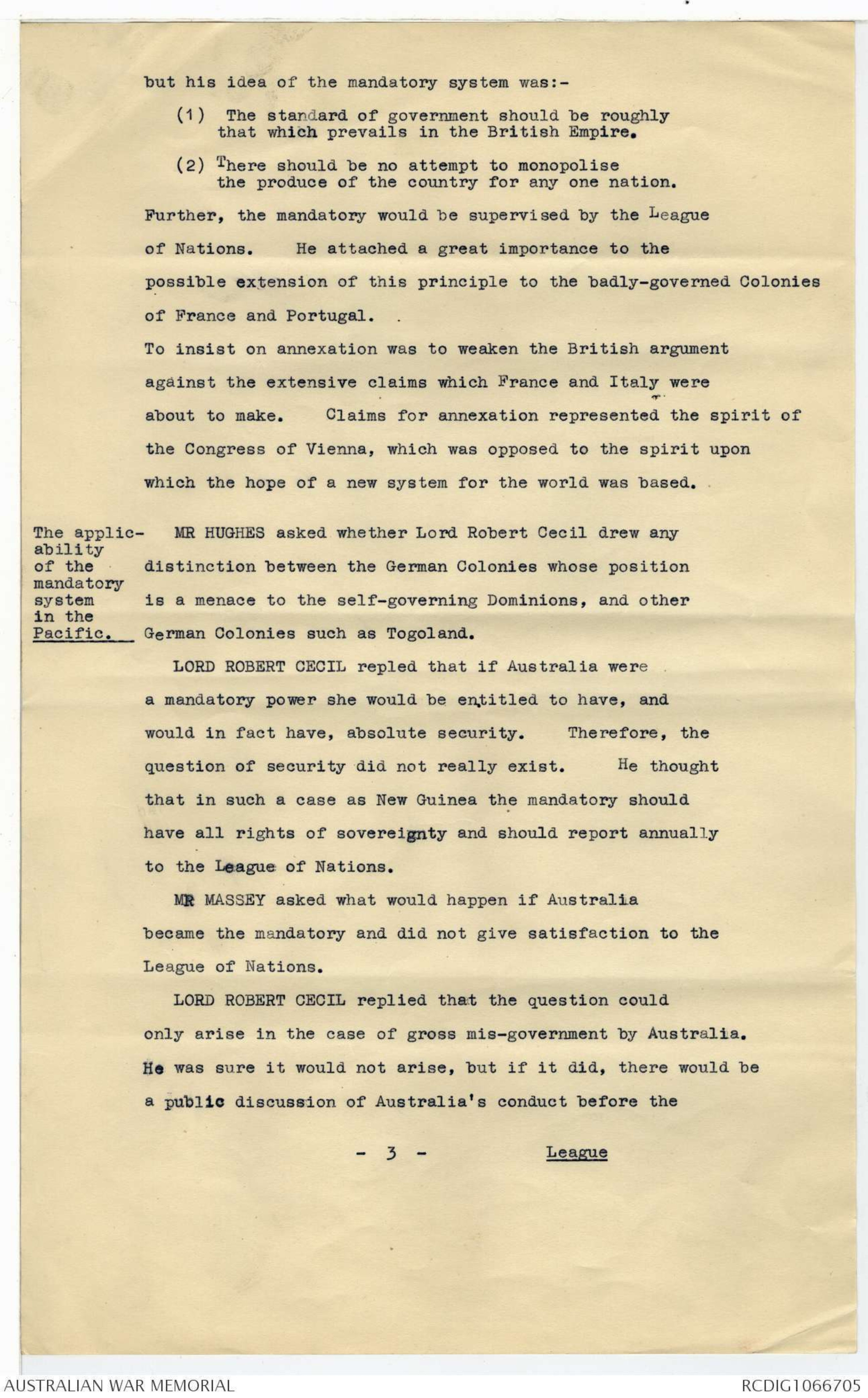

but his idea of the mandatory system was :-

(1) The standard of government should be roughly

that which prevails in the British Empire.

(2) There should be no attempt to monopolise

the produce of the country for any one nation.

Further, the mandatory would be supervised by the League

of Nations. He attached a great importance to the

possible extension of this principle to the badly-governed Colonies

of France and Portugal.

To insist on annexation was to weaken the British argument

against the extensive claims which France and Italy were

about to make. Claims for annexation represented the spirit of

the Congress of Vienna, which was opposed to the spirit upon

which the hope of a new system for the world was based.

[*The applicability

of the

mandatory

system

in the

Pacific*]

MR HUGHES asked whether Lord Robert Cecil drew any

distinction between the German Colonies whose position

is a menace to the self-governing Dominions, and other

German Colonies such as Togoland.

LORD ROBERT CECIL replied that if Australia were

a mandatory power she would be entitled to have, and

would in fact have, absolute security. Therefore, the

question of security did not really exist. He thought

that in such a case as New Guinea the mandatory should

have all rights of sovereignty and should report annually

to the League of Nations.

MR MASSEY asked what would happen if Australia

became the mandatory and did not give satisfaction to the

League of Nations.

LORD ROBERT CECIL replied that the question could

only arise in the case of gross mis-government by Australia.

He was sure it would not arise, but if it did, there would be

a public discussion of Australia's conduct before the

-3-

League

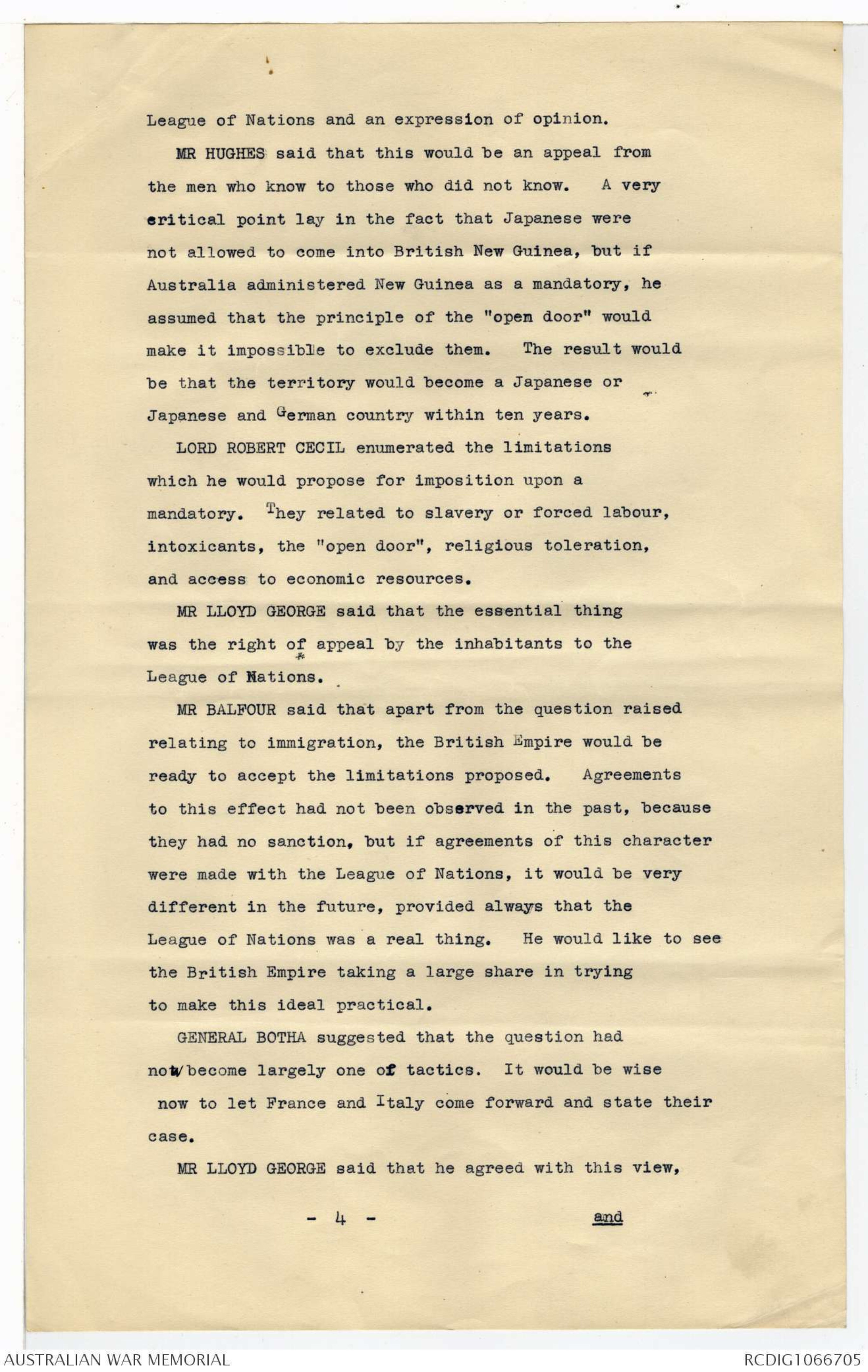

League of Nations and an expression of opinion.

MR HUGHES said that this would be an appeal from

the men who know to those who did not know. A very

critical point lay in the fact that Japanese were

not allowed to come into British New Guinea, but if

Australia administered New Guinea as a mandatory, he

assumed that the principle of the "open door" would

make it impossible to exclude them. The result would

be that the territory would become a Japanese or

Japanese and German country within ten years.

LORD ROBERT CECIL enumerated the limitations

which he would propose for imposition upon a

mandatory. They related to slavery or forced labour,

intoxicants, the "open door", religious toleration,

and access to economic resources.

MR LLOYD GEORGE said that the essential thing

was the right of appeal by the inhabitants to the

League of Nations.

MR BALFOUR said that apart from the question raised

relating to immigration, the British Empire would be

ready to accept the limitations proposed. Agreements

to this effect had not been observed in the past, because

they had no sanction, but if agreements of this character

were made with the League of Nations, it would be very

different in the future, provided always that the

League of Nations was a real thing. He would like to see

the British Empire taking a large share in trying

to make this ideal practical.

GENERAL BOTHA suggested that the question had

now become largely one of tactics. It would be wise

now to let France and Italy come forward and state their

case.

MR LLOYD GEORGE said that he agreed with this view,

-4-

and

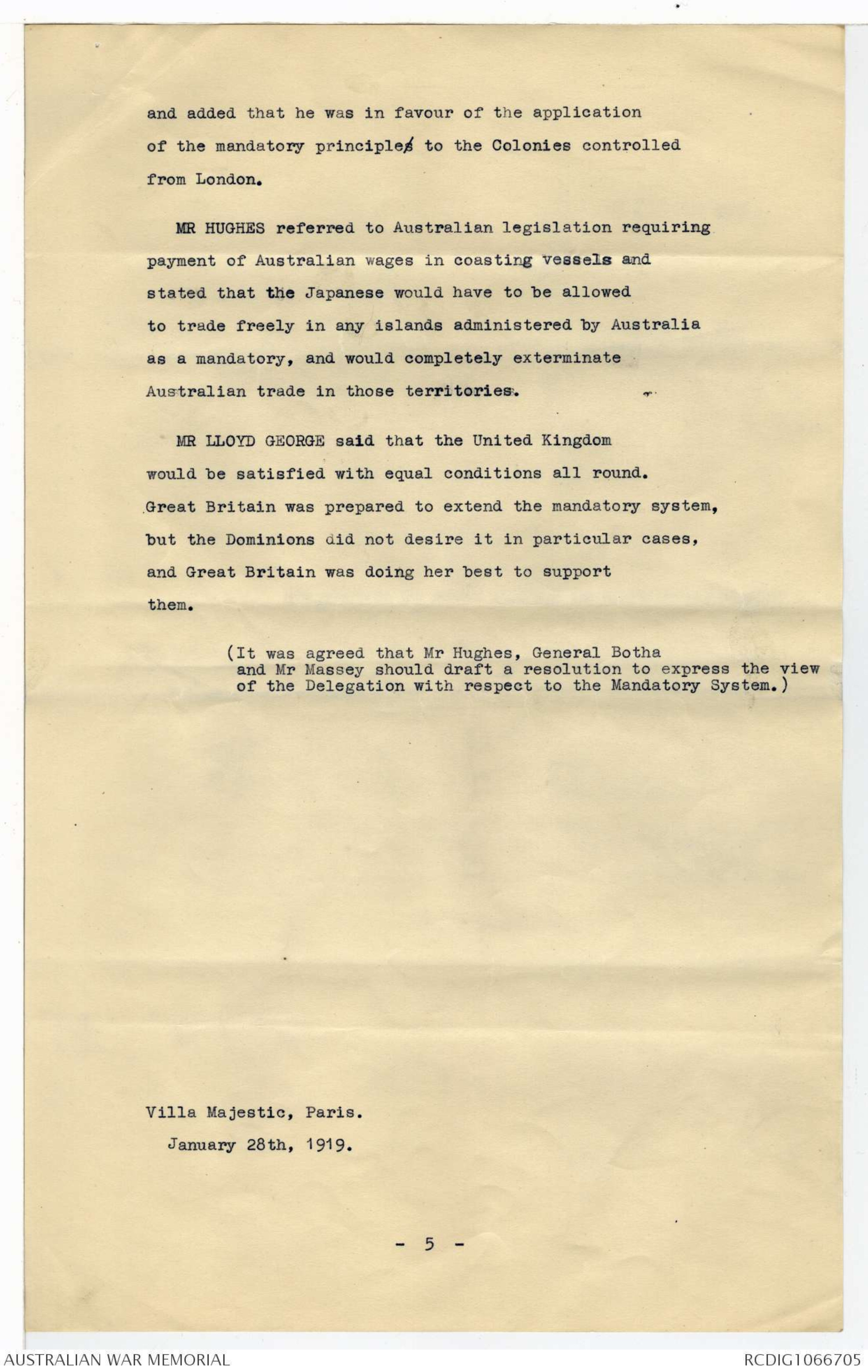

and added that he was in favour of the application

of the mandatory principles to the Colonies controlled

from London.

MR HUGHES referred to Australian legislation requiring

payment of Australian wages in coasting vessels and

stated that the Japanese would have to be allowed

to trade freely in any islands administered by Australia

as a mandatory, and would completely exterminate

Australian trade in those territories.

MR LLOYD GEORGE said that the United Kingdom

would be satisfied with equal conditions all round.

Great Britain was prepared to extend the mandatory system,

but the Dominions did not desire it in particular cases,

and Great Britain was doing her best to support

them.

(It was agreed that Mr Hughes, General Botha

and Mr Massey should draft a resolution to express the view

of the Delegation with respect to the Mandatory System.)

Villa Majestic, Paris.

January 28th, 1919.

-5-

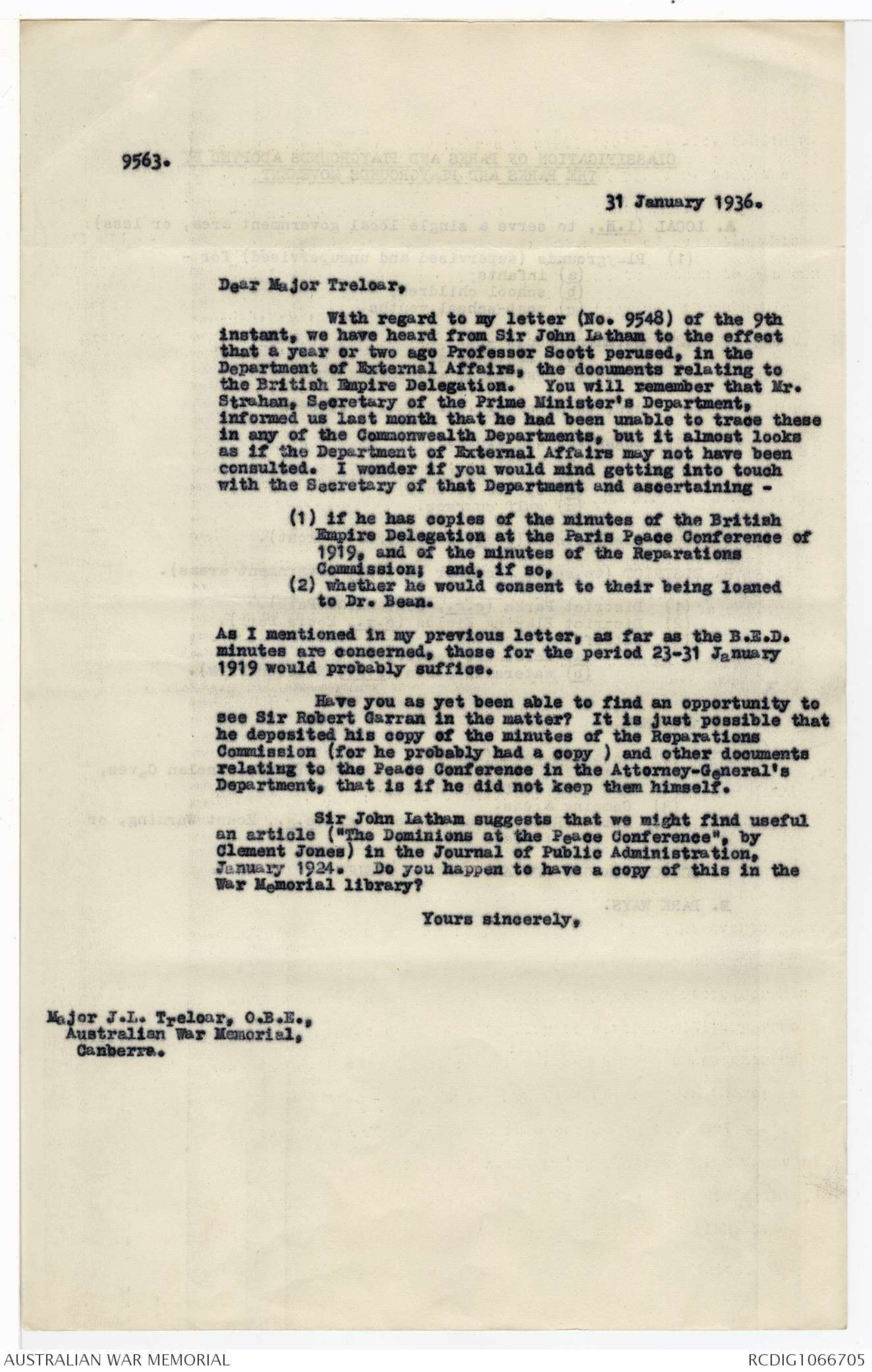

9563.

31 January 1936.

Dear Major Treloar,

With regard to my letter (No. 9548) of the 9th

instant, we have heard from Sir John Latham to the effect

that a year or two ago Professor Scott perused, in the

Department of External Affairs, the documents relating to

the British Empire Delegation. You will remember that Mr.

Strahan, Secretary of the Prime Minister's Department,

informed us last month that he had been unable to trace these

in any of the Commonwealth Departments, but it almost looks

as if the Department of External Affairs may not have been

consulted. I wonder if you would mind getting into touch

with the Secretary of that Department and ascertaining -

(1) if he has copies of the minutes of the British

Empire Delegation at the Paris Peace Conference of

1919, and of the minutes of the Reparations

Commission; and, if so,

(2) whether he would consent to their being loaned

to Dr. Bean.

As I mentioned in my previous letter, as far as the B.E.D.

minutes are concerned, those for the period 23-31 January

1919 would probably suffice.

Have you as yet been able to find an opportunity to

see Sir Robert Garran in the matter? It is just possible that

he deposited his copy of the minutes of the Reparations

Commission (for he probably had a copy ) and other documents

relating to the Peace Conference in the Attorney-General's

Department, that is if he did not keep them himself.

Sir John Latham suggests that we might find useful

an article ("The Dominions at the Peace Conference", by

Clement Jones) in the Journal of Public Administration,

January 1924. Do you happen to have a copy of this in the

War Memorial library?

Yours sincerely,

Major J.L. Treloar, O.B.E.

Australian War Memorial,

Canberra.

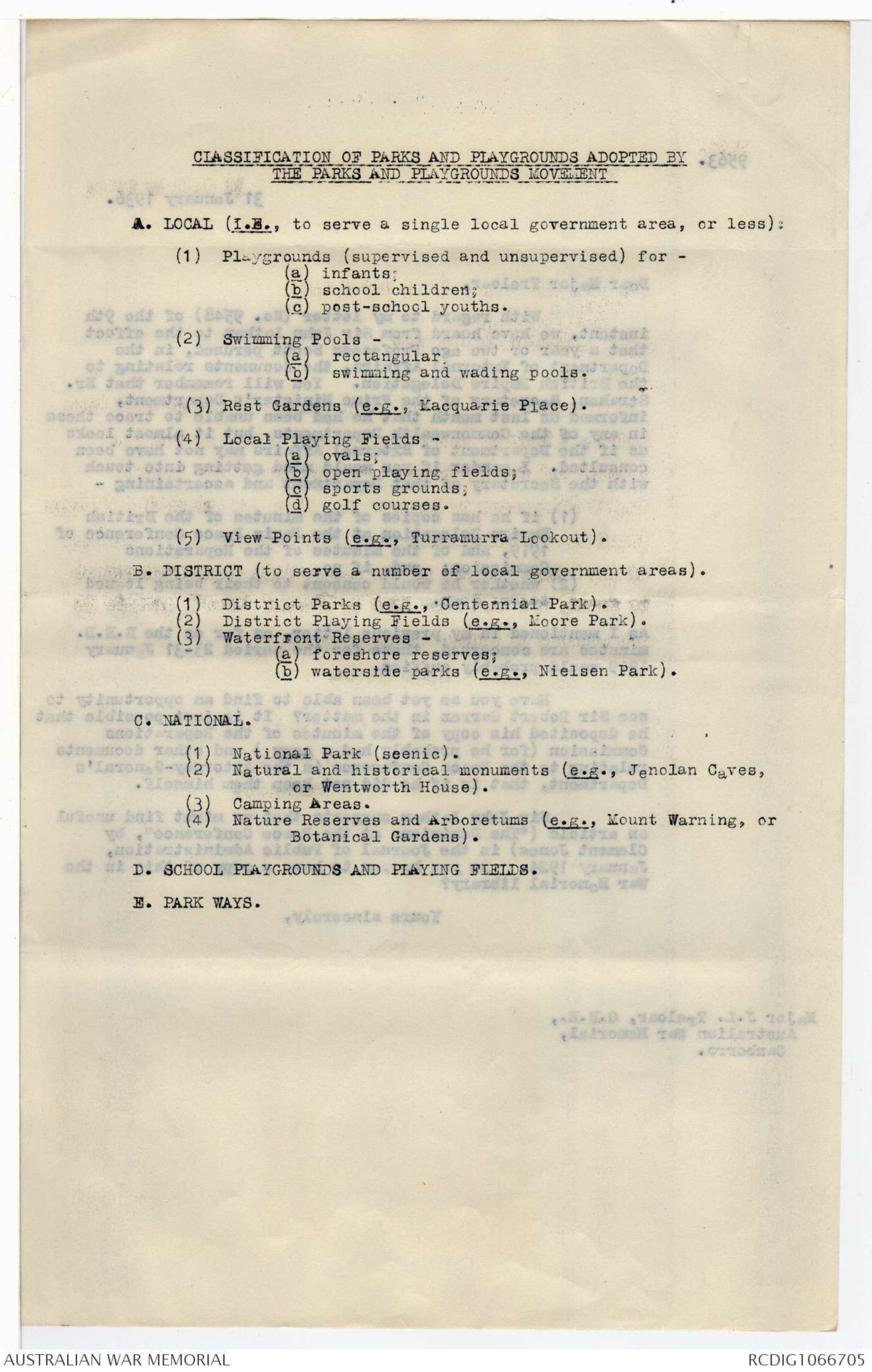

CLASSIFICATION OF PARKS AND PLAYGROUNDS ADOPTED BY

THE PARKS AND PLAYGROUNDS MOVEMENT

A. LOCAL (I.E., to serve a single local government area, or less):

(1) Playgrounds (supervised and unsupervised) for -

(a)infants;

(b)school children;

(c) post-school youths.

(2) Swimming Pools -

(a)rectangular

(b)swimming and wading pools.

(3) Rest Gardens (e.g., Macquarie Place).

(4) Local Playing Fields

(a) ovals,

(b) open playing fields;

(c) sports grounds;

(d) golf courses.

(5) View Points (e.g., Turramurra Lookout).

B. DISTRICT (to serve a number of local government areas).

(1) District Parks (e.g., Centennial Park).

(2) District Playing Fields (e.g., Moore Park).

(3) Waterfront Reserves -

(a) foreshore reserves:

b) waterside parks (e.g., Nielsen Park).

C. NATIONAL.

(1) National Park (scenic).

(2) Natural and historical monuments (e.g., Jenolan Caves,

or Wentworth House).

(3) Camping Areas.

(a) Nature Reserves and Arboretums

(e.g., Mount Warning, or

Botanical Gardens).

D. SCHOOL PLAYGROUNDS AND PLAYING FIELDS.

E. PARK WAYS.

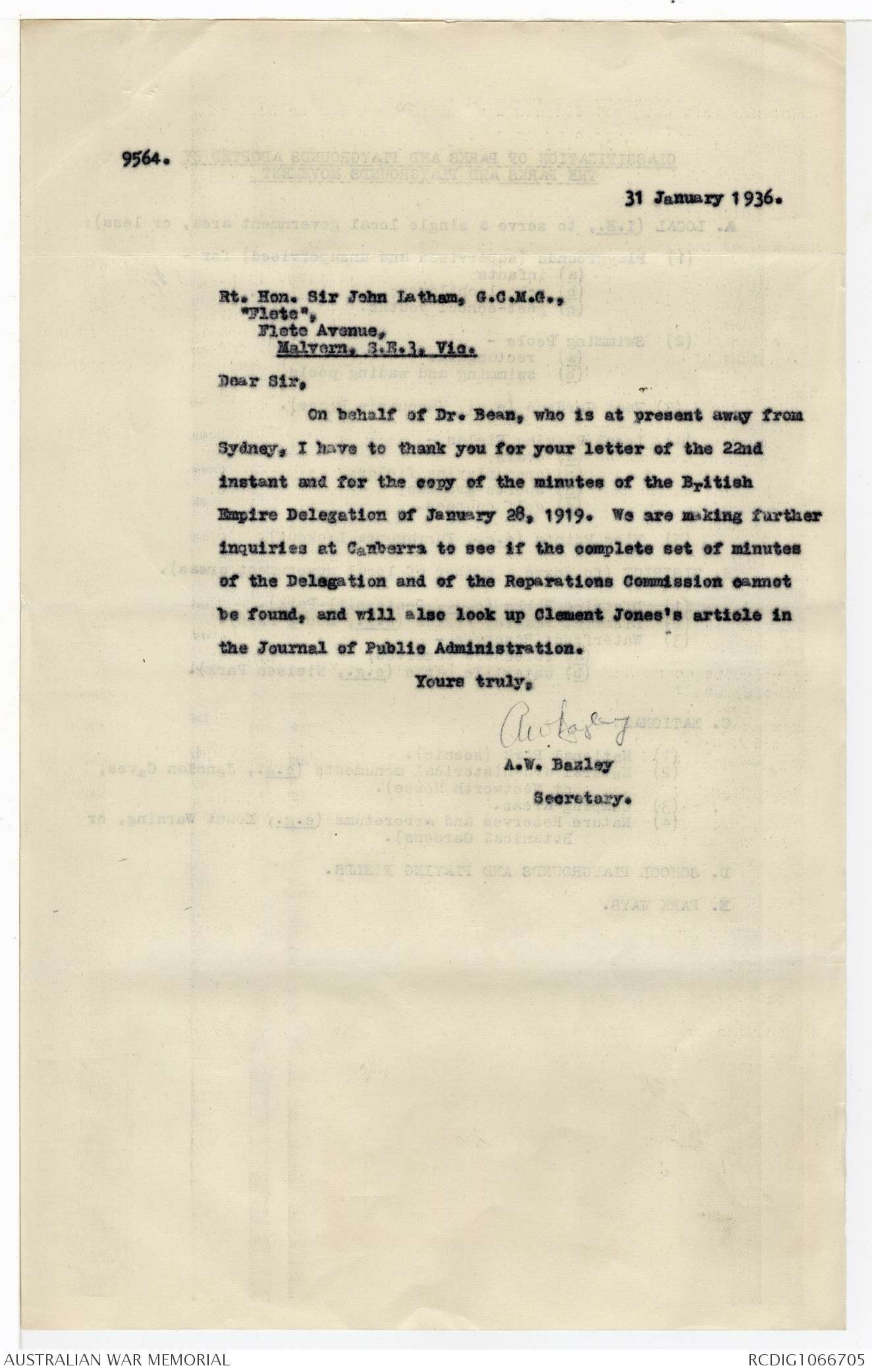

9564.

31 January 1936.

Rt. Hon. Sir John Latham, G.C.M.G.,

"Flete",

Flete Avenue,

Malvern, S.E.3, Vic.

Dear Sir,

On behalf of Dr. Bean, who is at present away from

Sydney, I have to thank you for your letter of the 22nd

instant and for the copy of the minutes of the British

Empire Delegation of January 28, 1919. We are making further

inquiries at Canberra to see if the complete set of minutes

of the Delegation and of the Reparations Commission cannot

be found, and will also look up Clement Jones's article in

the Journal of Public Administration.

Yours truly.

AWBazley

A.W. Bazley

Secretary.

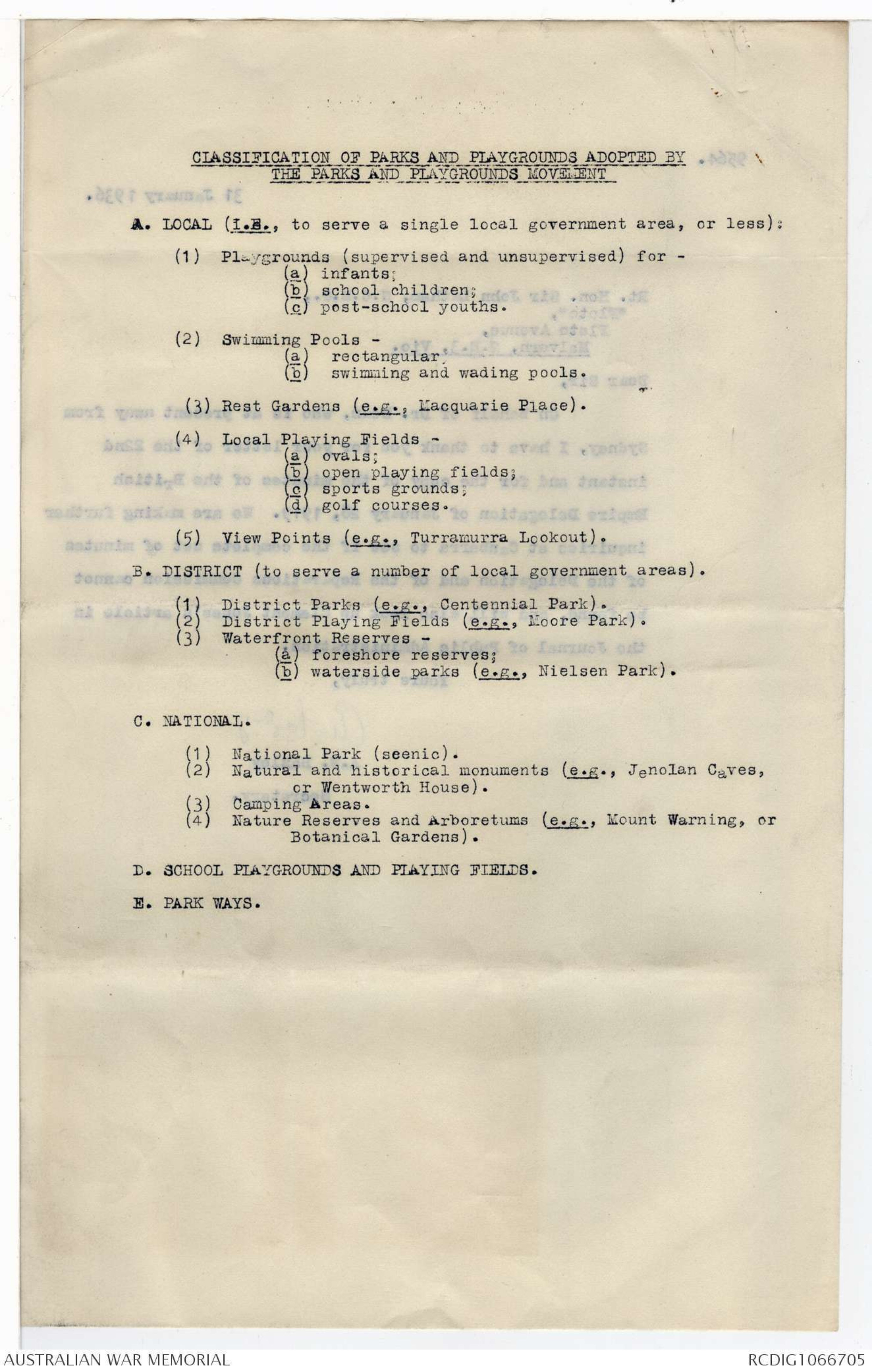

CLASSIFICATION OF PARKS AND PLAYGROUNDS ADOPTED BY

THE PARKS AND PLAYGROUNDS MOVEMENT

A. LOCAL (I.E., to serve a single local government area, or less):

(1) Playgrounds (supervised and unsupervised) for -

(a) infants;

(b) school children;

(c) post-school youths.

(2) Swimming Pools -

(a) rectangular

(b) swimming and wading pools.

(3) Rest Gardens (e.g., Macquarie Place).

(4) Local Playing Fields

(a) ovals,

(b) open playing fields;

(c) sports grounds;

(d) golf courses.

(5) View Points (e.g., Turramurra Lookout).

B. DISTRICT (to serve a number of local government areas).

(1) District Parks (e.g., Centennial Park).

(2) District Playing Fields (e.g., Moore Park).

(3) Waterfront Reserves -

(a) foreshore reserves:

(b) waterside parks (e.g., Nielsen Park).

C. NATIONAL.

(1) National Park (scenic).

(2) Natural and historical monuments (e.g., Jenolan Caves,

or Wentworth House).

(3) Camping Areas.

(a) Nature Reserves and Arboretums (e.g., Mount Warning, or

Botanical Gardens).

D. SCHOOL PLAYGROUNDS AND PLAYING FIELDS.

E. PARK WAYS.

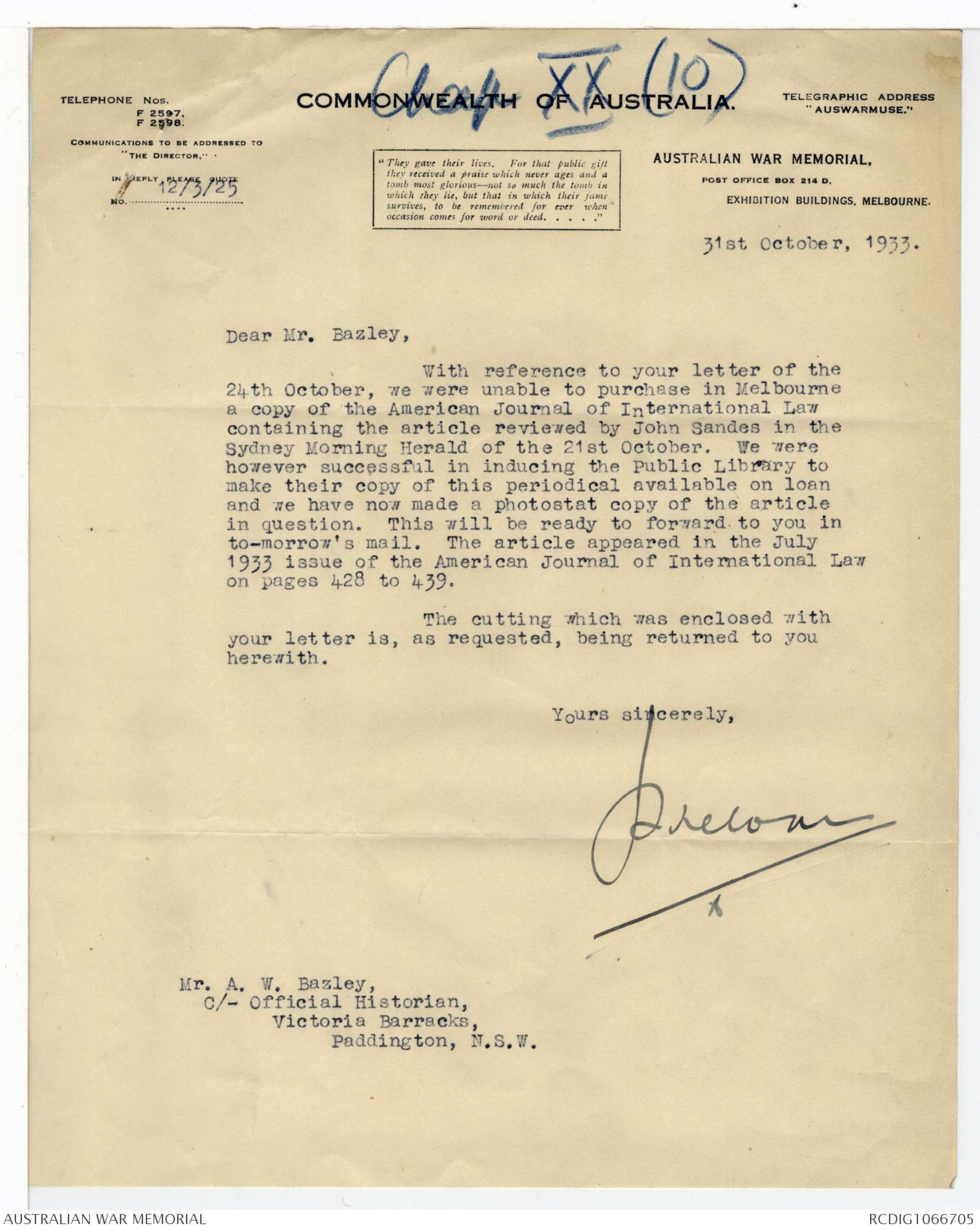

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA

Chap XX (10)

TELEGRAPHIC ADDRESS

'AUSWARMUSE.'

AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL,

POST OFFICE BOX 214D

EXHIBITION BUILDINGS, MELBOURNE

TELEPHONE Nos.

F 2597,

F 2598.

COMMUNICATIONS TO BE ADDRESS TO

"THE DIRECTOR,"

IN REPLY, PLEASE QUOTE

NO 12/3/25

"They gave their lives. For that public gift

they received a praise which never ages and a

tomb most glorious - not so much the tomb in

which they lie but that in which their fame

survives, to be remembers for every when

occasion comes for word or deed ...."

31st October, 1933.

Dear Mr. Bazley,

With reference to your letter of the

24th October, we were unable to purchase in Melbourne

a copy of the American Journal of International Law

containing the article reviewed by John Sandes in the

Sydney Morning Herald of the 21st October. We were

however successful in inducing the Public Library to

make their copy of this periodical available on loan

and we have now made a photostat copy of the article

in question. This will be ready to forward to you in

to-morrow's mail. The article appeared in the July

1933 issue of the American Journal of International Law

on pages 428 to 439.

The cutting which was enclosed with

your letter is, as requested, being returned to you

herewith.

Yours sincerely,

[[??]]

Mr. A. W. Bazley

C/- Official Historian,

Victoria Barracks

Paddington, N.S.W.

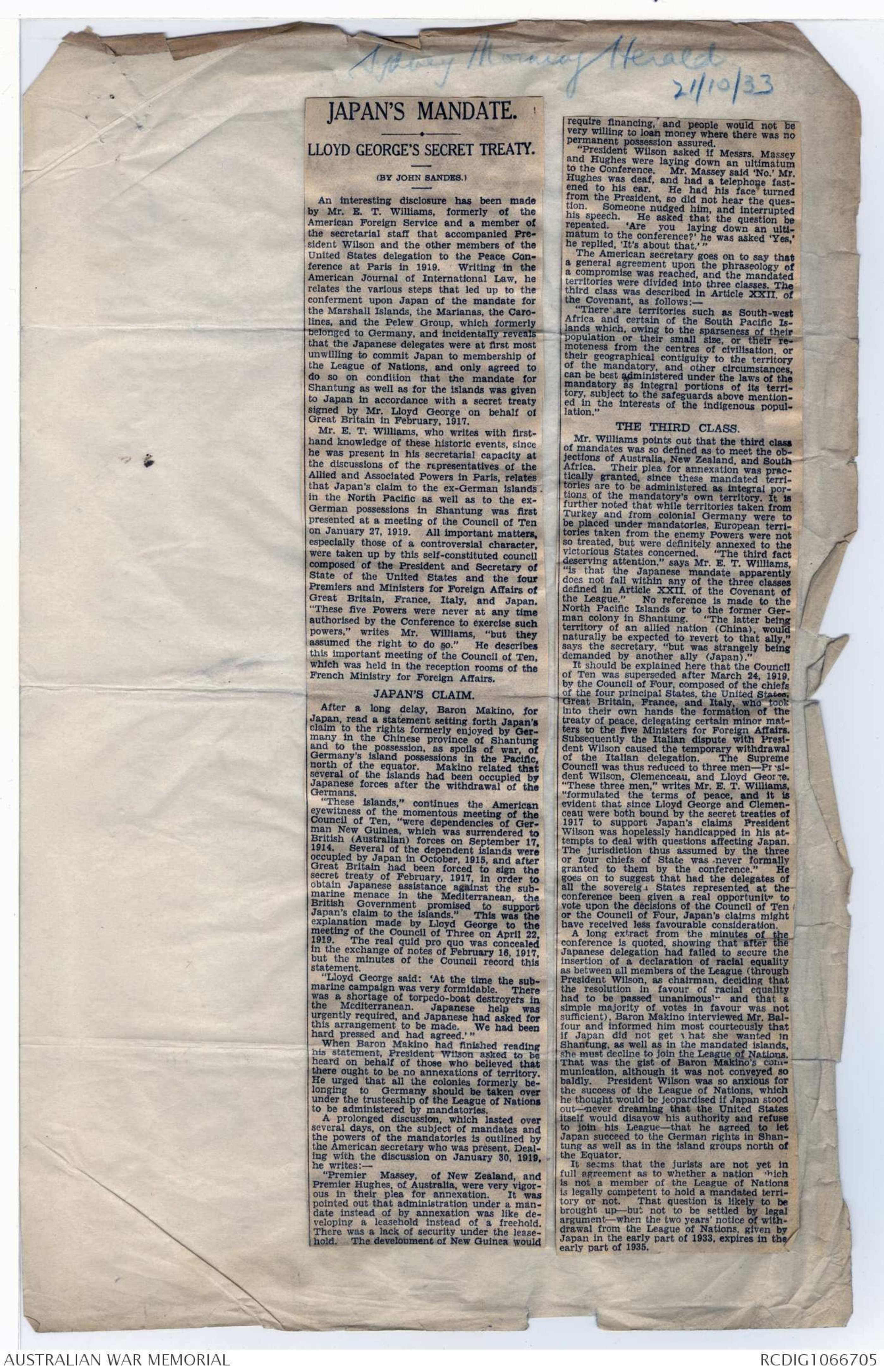

Sydney Morning Herald 21/10/33

JAPAN'S MANDATE

LLOYD GEORGE'S SECRET TREATY

(BY JOHN SANDES.)

An interesting disclosure has been made

by Mr. E.T. Williams, formerly of the

American Foreign Service and a member of

the secretarial staff that accompanied President

Wilson and the other members of the

United States delegation to the Peace Conference

at Paris in 1919. Writing in the

American Journal of International Law, he

relates the various steps that led up to the

conferment upon Japan of the mandate for

the Marshall Islands, the Marianas, the Carolines,

and the Pelew Group, which formerly

belonged to Germany and incidentally reveals

that the Japanese delegates were at first most

unwilling to commit Japan to membership of

the League of Nations, and only agreed to

do so on condition that the mandate for

Shantung as well as for the islands was given

to Japan in accordance with the secret treaty

signed by Mr. Lloyd George on behalf of

Great Britain in February, 1917.

Mr. E. T. Williams, who writes with first-hand

knowledge of these historic events, since

he was present in his secretarial capacity at

the discussions of the representatives of the

Allied and Associated Powers in Paris, relates

that Japan's claim to the ex-German islands

in the North Pacific as well as to the ex-German

possessions in Shantung was first

presented at a meeting of the Council of Ten

on January 27, 1919. All important matters,

especially those of a controversial character,

were taken up by this self-constituted council

composed of the President and Secretary of

State of the United States and the four

Premiers and Ministers for Foreign Affairs of

Great Britain, France, Italy, and Japan.

"These five Powers were never at any time

authorised by the Conference to exercise such

powers," writes Mr. Williams, "but they

assumed the right to do so." He describes

this important meeting of the Council of Ten,

which was held in the reception rooms of the

French Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

JAPAN'S CLAIM

After a long delay, Baron Makino, for

Japan, read a statement setting forth Japan's

claim to the rights formerly enjoyed by Germany

in the Chinese province of Shantung

and to the possession, as spoils of war, of

Germany's island possessions in the Pacific,

north of the equator. Makino related that

several of the islands had been occupied by

Japanese forces after the withdrawal of the

Germans.

"These islands," continues the American

eyewitness of the momentous meeting of the

Council of Ten, "were dependencies of German

New Guinea, which was surrendered to

British (Australian) forces on September 17,

1914. Several of the dependent islands were

occupied by Japan in October, 1915, and after

Great Britain had been forced to sign the

secret treaty of February, 1917, in order to

obtain Japanese assistance against the submarine

menace in the Mediterranean, the

British Government promised to support

Japan's claim to the islands." This was the

explanation made by Lloyd George to the

meeting of the Council of Three on April 22,

1919. The real quid pro quo was concealed

in the exchange of notes of February 16, 1917,

but the minutes of the Council record this

statement.

"Lloyd George said: 'At the time, the submarine

campaign was very formidable. There

was a shortage of torpedo-boat destroyers in

the Mediterranean. Japanese help was

urgently required, and Japanese has asked for

this arrangement to be made. We had been

hard pressed and had agreed.'"

When Baron Makino had finished reading

his statement, President Wilson asked to be

heard on behalf of those who believed that

there ought to be no annexations of territory.

He urged that all the colonies formerly belonging

to Germany should be taken over

under the trusteeship of the League of Nations

to be administered by mandatories.

A prolonged discussion, which lasted over

several days, on the subject of mandates and

the powers of the mandatories is outlined by

the American secretary who was present. Dealing

with the discussion on January 30, 1919

he writes:-

"Premier Massey, of New Zealand, and

Premier Hughes of Australia, were very vigorous

in their plea of annexation. It was

pointed out that administration under a mandate

instead of by annexation was like developing

a leasehold instead of a freehold.

There was a lack of security under the leasehold.

The development of New Guinea would

require financing, and people would not be

very willing to loan money where there was no

permanent possession assured.

"President Wilson asked if Messrs. Massey

and Hughes were laying down an ultimatum

to the Conference. Mr Massey said "No." Mr. Hughes

was deaf, and had a telephone fastened

to his ear. He had his face turned

from the President, so did not hear the question.

Someone nudged him, and interrupted

his speech. He asked that the question be

repeated. 'Are you laying down an ultimatum

to the conference?" he was asked 'Yes,'

he replied, 'It's about that.'"

The American secretary goes on to say that

a general agreement upon the phraseology of

a compromise was reached, and the mandated

territories were divided into three classes. The

third class was described in Article XXII of

the Covenant, as follows:-

"There are territories such as South-west

Africa and certain of the South Pacific Islands

which owing to the sparseness of their

population or their small size, or the remoteness

from the centres of civilisation, or

their geographical contiguity to the territory

of the mandatory, and other circumstances,

can be best administered under the laws of the

mandatory as integral portions of its territory,

subject to the safeguards abovementioned

in the interests on the indigenous population."

THE THIRD CLASS

Mr. Williams points out that the third class

of mandates was so defined as to meet the objections

of Australia, New Zealand, and South

Africa. Their plea for annexation was practically

granted, since these mandated territories

are to be administered as integral portions

of the mandatory's own territory. It is

further noted that while territories taken from

Turkey and from colonial Germany were to

be placed under mandatories, European territories

taken from the enemy Powers were not

so treated, but were definitely annexed to the

victorious States concerned. "The third fact

deserving attention," says Mr. E. T. Williams,

"is that the Japanese mandate apparently

does not fall within any of the three classes

defined in Article XXII of the Covenant of

the League." No reference is made to the

North Pacific Islands or to the former German

colony in Shantung. "The latter being

territory of an allied nation (China), would

naturally be expected to revert to that ally,"

says the secretary, "but was strangely being

demanded by another ally (Japan)."

It should be explained here that the Council

of Ten was superseded after March 24, 1919,

by the Council of Four, composed of the chiefs

of the four principal States, the United States,

Great Britain, France, and Italy who took

into their own hands the formation of the

treaty of peace, delegating certain minor matters

to the five Ministers for Foreign Affairs.

Subsequently the Italian dispute with President

Wilson caused the temporary withdrawal

of the Italian delegation. The Supreme

Council was thus reduced to three men - President

Wilson, Clemenceau, and Lloyd George.

"These three men," writes Mr. E. T. Williams,

"formulated the terms of peace, and it is

evident that since Lloyd George and Clemenceau

were both bound by the secret treaties of

1917 to support Japan's claims President

Wilson was hopelessly handicapped in his attempts

to deal with questions affecting Japan.

The jurisdiction thus assumed by the three

or four chiefs of State was never formally

granted to them by the conference." He

goes on to suggest that had the delegates of

all the sovereign States represented at the

conference been given a real opportunity to

vote upon the decisions of the Council of Ten

or the Council of Four, Japan's claims might

have received less favourable consideration.

A long extract from the minutes of the

conference is quoted, showing that after the

Japanese delegation had failed to secure the

insertion of a declaration of racial equality

as between all members of the League (through

President Wilson, as chairman, decided that

the resolution in favour of racial equality

had to be passed unanimous1" and that a

simple majority of votes in favour was not

sufficient). Baron Makino interviewed Mr Balfour

and informed him most courteously that

if Japan did not get what she wanted in

Shantung, as well as in the mandated islands,

she must decline to join the League of Nations.

That was the gist of Baron Makino's communication,

although it was not conveyed so

baldly. President Wilson was so anxious for

the success of the League of Nations, which

he thought would be jeopardised if Japan stood

out - never dreaming that the United States

itself would disavow his authority and refuse

to join his League - that he agreed to let

Japan succeed to the German rights in Shantung

as well as in the island groups north of

the Equator.

It seems that the jurists are not yet in

full agreement as to whether a nation which

is not a member of the League of Nations

is legally competent to hold a mandated territory

or not. That question is likely to be

brought up - but not to be settled by legal

argument - when the two years' notice of withdrawal

from the League of Nations, given by

Japan in the early part of 1933, expires in the

early part of 1935.

Sam scott

Sam scottThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.