Charles E W Bean, Diaries, AWM38 3DRL 606/269/1 - 1918 - 1936 - Part 2

8

ments of all the self-governing Dominions, and they have

passed bills or motions which are described as ratifying

it, but the actual ratification is a single act which has been

performed by the King.

Thus I do not attach a great deal of importance, from a

practical point of view, to the separate representation of the

Dominions at the formal meetings of the full Conference, or

to the separate signature of the Treaty. But when the subject

of the League of Nations is considered, it will be seen

that a very real separation is established for the future, and

that this may bring about most important developments.

WHITE AUSTRALIA.

The subject of a White Australia in connection with the

Conference has been dealt with by Mr. Hughes in some

detail. It may be interesting, in the first place, to explain

how the matter arose. The Japanese delegates formulated a

demand for the recognition of the principle of racial

equality in the Covenant of the League of Nations. At the

time when this question was first raised by the Japanese

Delegates in Paris (it had already been raised by Mr.

Hughes in an interview which he had given to an American

pressman), the Covenant of the League of Nations was

under discussion by the Commission on the League of

Nations. President Wilson was Chairman of this Commission

and the representatives of the British Empire were

Lord Robert Cecil and General Smuts.

Before bringing their amendment before the Commission,

the Japanese representatives—who, as the result showed,

were very skilful diplomats—endeavored to enlist support,

and to remove obstacles in as many quarters as possible.

They interviewed all the representatives of other nations on

the Commission of the League of Nations. As soon as they

approached the British representatives they were at once

met with difficulties arising from the immigration restriction

policies of Australia, South Africa and, in a smaller degree,

Canada. They interviewed the Dominion representatives

and made various proposals, altering their formula in many

ways, but, as Mr. Hughes has now stated publicly, they

would not give an undertaking that any of the proposed

formulas would not cover the subject of immigration. It is a

mistake, therefore, to criticise the Australian representatives,

as some people have done, on the ground that the

Japanese request for a recognition of racial equality was a

harmless generality, which might safely, and, indeed, wisely,

have been conceded. At the stage which matters had then

reached, it was clear that the concession would not have

9

been harmless, and the Dominions refused to accept the

proposed amendment. The attitude of the British delegates on

the Commission of the League of Nations was on this subject

determined by the attitude of the Dominions, and they

therefore opposed the amendment.

When the amendment was put to the Commission of the

League it was carried by 11 votes to 7. (This announcement

has been made in the press.) President Wilson took

the responsibility of ruling that it was not carried, declaring

that any amendment of the draft of the Covenant then

before the Commission could only be made by a unanimous

vote. (At the immediately previous meeting of the Commission,

Geneva had been selected as the capital of the

League by a majority of only two votes, but it is possible

to draw a technical distinction between the two cases.)

This was, however, a bold step to take. Our view, it will

be seen, had gained but little support. I cannot say what

efforts were made to enlist support for it, or to prevent the

question being raised, but whatever was done had proved

to be ineffectual. The vote of the Commission may be taken

as an indication of the probable vote at a full meeting of the

Conference. It was fortunate for Australia that President

Wilson adopted a procedure, remarkable as it may appear

which resulted in the Japanese amendment not being included

in the Covenant as submitted to the Peace Conference.

But there was still another stage. It was open to Japan

to move the amendment at the Peace Conference itself. If

this had been done, the position would have been very serious.

It was not done. Baron Makino confined himself to a protest.

delivered in dignified and weighty language. How it came

about that the Japanese representatives adopted this course,

instead of moving the amendment in a Conference which they

had reason to believe would have supported their claim, is

one of the interesting stories of the Conference which

higher authorities have not yet told, and upon which I cannot,

therefore, speak.

The terms of that protest should be read by every Australian,

in order that they may understand the point of view

from which the Japanese public criticises our policy.

The principle of White Australia is almost a religion in

Australia. Upon it depends the possibility of the continuance

of white democracy—indeed, of any democracy, in a

real sense—in this continent. Any surrender of the policy

is inconceivable—it rests upon the right of every self-governing

community to determine the ingredients of its own

population. If that right is surrendered, the essence of

self-government disappears.

10

But it must be remembered that there are various methods

of expressing a policy, and various means of applying a

principle. It also should not be forgotten that the principle

underlying a policy is frequently misunderstood in foreign

countries. It is vitally important for Australia to understand

her White Australia policy herself—to get at the root of it,

and view it in all its aspects. When the policy is so considered,

it will be found that it contains nothing that can

justly be regarded as offensive by any foreign nation.

The next step, after understanding it ourselves, is to

explain it to those who object, or are inclined to object, to it.

This explanation must be the work of well-instructed and

skilful leaders. It has not proved impossible to adjust our

similar difficulties with India. It may be that a similar

solution will satisfy the Japanese, and, at the same time,

preserve, and even strengthen, our White Australia policy.

THE PRINCIPLE OF MANDATES.

It is regrettable, but not surprising, that the principle of

mandates for former German Colonies has been

misunderstood, and consequently abused, in Australia. Let me

mention a few general considerations in the first place.

1. Again and again our leaders declared that the British

Empire did not enter the war for the sake of aggrandisement,

and that Great Britain did not desire to secure any

annexations. The war was a war of defence - it was a fight

for security - it was not a fight to extend the boundaries of

our already vast Empire. Any annexations of territory by

the Empire would have exposed us to most serious charges

of breach of faith, and would have most gravely damaged

our moral prestige.

2. In the next place, the British race has always claimed

that its occupation of territories inhabited by backward

native races was in the nature of a trusteeship for civilisation.

We have called it the “white man’s burden- we

have again and again asserted that our object was the

well-being of the natives, and not the promotion of our own

interests, commercial or otherwise. The principle of mandates

in relation to the former German colonies only states

in explicit terms what the British race has always professed

to be the real terms upon which large areas of our Empire

are held. This is the essence of a mandate :- A territory

administered under a mandate is not to be administered for

the benefit of the Power to whom the administration is

entrusted, but for the benefit of the inhabitants of the

country, and subject to safeguards for their protection.

3. The principle of mandates must be looked at from a

11

world point of view. It must be remembered that if the

British Empire, or any part of it, had annexed colonial

territory, other Allied Powers would have been equally

entitled to adopt a similar course of action. Not only the

fate of the Pacific Islands was in question, but also the

destiny of vast areas in Central and East Africa, in

Mesopotamia, Palestine, and Syria and Asia Minor. Great

Britain had given pledges that she would not annex

Mesopotamia and other parts of the former Turkish Empire, but

it was most desirable for British interests that Britain

should have some effective standing in Mesopotamia. The

principle of mandates afforded an opportunity of achieving

these objects, and of keeping faith with the world and with

the races to whom specific promises had been made.

To come now to the specific case in which Australia is

interested, viz., the Pacific Islands. I have no hesitation in

saying that it would have been a most unfortunate, and

possibly a disastrous, thing for Australia, if Australia had

been permitted to annex the islands constituting former

German New Guinea. It must be remembered that from a

practical point of view, it had to be assumed that the

conditions upon which the German Pacific Islands should

be held would be the same, whatever the situation of those

islands. In accepting limitations for ourselves, therefore.

we were imposing limitations upon others. If we had

obtained complete freedom for ourselves, others also would

have had complete freedom.

There are three types of mandates, and the Australian

mandate is one of the third type.

The first type applies to the Turkish Empire. In these

cases, the existence of communities as independent

nations, is to be provisionally recognised, subject to the

rendering of administrative advice and assistance by the

mandatory, until such time as they are able to stand alone.

The second type of mandate applies to Central Africa.

The limitation upon the Powers of the mandatory state is

greater than in the case of South-West Africa and the

islands of the Pacific, for in the second type the mandatory

is bound to-“secure equal opoprtunities for the trade and

commerce of other members of the League;” while in the

third type, this limitation is absent, and it is further provided

that the territory subject to the mandate may be

administered as an intergral portion of the mandatory state. The

special provision requiring the open door in the second type

of mandate is due to the fact that Central Africa contains

vast stores of raw materials which are needed by all the

nations of the world. Further, in these territories there is

12

no immigration problem such as exists in Australia and the

neighbouring islands.

It must be observed that “equal opportunities for trade

and commerce” involve equality of conditions with respect

to the entry of men as well as of goods. If this condition

applied in the islands of former German New Guinea, there

is little doubt that they would soon be over-run by alien

immigrants, and that the White Australia policy would be

gravely endangered.

To what limitations have we submitted because Australia

has a mandate instead of sovereignty of the islands? We

have promised to tolerate all law abiding religions, to prohibit

the slave trade, the arms traffic and the liquor traffic,

not to train the natives as a military force except for

purposes of defence, and not to establish fortifications or

military or naval bases. We have also promised to render

to the Council of the League of Nations an annual report on

the islands with the administration of which Australia is

entrusted.

Look at these limitations. Freedom of conscience and

religion. The Australian people would have insisted upon

this in any case. The slave trade, arms traffic, liquor traffic

-the same applies. Fortifications or military or naval bases

-this limitation applies to others, and it must be

remembered that a friend of to-day might be a foe to-morrow

Shortly, the limitation is greatly in Australia’s interests.

The Caroline and Marshall Islands are half-way between

Australia and Japan. There is, therefore, no doubt whatever

that the mandate is much more favorable to Australia than

annexation would have been.

The prohibition of fortifications and of military and naval

bases is not of the first importance to Australia in any case.

Australia owns British New Guinea, and Great Britain owns

islands scattered round the Pacific in proximity to German

New Guinea. Any of these islands may be used for military

or naval purposes without restriction. Australia has gained

security in obtaining full power to exclude any potential

enemy from the islands north of the Equator. We have

power to apply such laws as we choose to enact, for it is

expressly provided that these territories can be “administered

under the laws of the mandatory as integral portions

of its territory.” This positive provision, coupled with the

absence of the “open door” requirement, makes the White

Australia policy secure so far as these islands are concerned,

and so far as there can be efficacy in international covenants.

Under the eyes of the world, Australia is entrusted with

the government of these backward countries. Australia is

to make an annual report of the League of Nations upon the

13

territory committed to her charge. It should be, and doubtless

will be, a point of honor with Australians that we should

do our best, and that we should endeavour to make our

administration a model which other countries may be glad

to copy. It will not be all plain sailing. Germany had a

deficit of some [Pound] 60,000 a year on the whole of the German

Pacific possessions—Samoa was, apparently, the only profitable

colony. But the earlier stages of administration in

tropical colonies are always the more expensive, and it may

be that Australia will be able to show a better statement of

accounts than was the case with Germany. We are nearer,

communication is easier and more rapid. Our responsible

Ministers will be able to inform themselves at first hand of

conditions in the territories, and Australia ought, therefore,

to obtain better results than Germany ever did.

The administration of these islands should provide opportunities

for the employment of some of our best men—some

of the men who, in the war, have shown capacity for handling

other men, for dealing with questions upon their merits,

and who have given evidence of adaptability to new and

strange conditions. It must be remembered, however, that

the administration must be civilian, and not military, in form

and character.

LEAGUE OF NATIONS.

The establishment of the League of Nations is one of the

greatest achievements of the Peace. Admitting that the

reality of the League is still to be demonstrated, and that the

League will have many difficulties to surmount, it is yet

no mean achievement to have obtained the concurrence of

the thirty-three Allied Delegations in the terms of the

Covenant of the League.

The aims of the League are set forth in the preamble to

the Covenant :—“To promote international co-operation and

to achieve international peace and security by the acceptance

of obligations not to resort to war; by the prescription of

open, just, and honorable relations between nations; by the

establishment of international law as the actual rule of

conduct among Governments; and by the maintenance of

justice and a scrupulous respect for all treaty obligations in

the dealings of organised peoples with one another.” These

aims may be condemned as idealistic and impossible in a

practical world, but, at least, it cannot be said that it is

not worth while trying to secure them.

Under the provisions of Article 1, Australia is an original

member of the League, and Article 3 accords to Australia a

representative upon the Assembly of the League. Each

Power has only one vote on the Assembly.

14

The Council consists of representatives of the Five Great

Powers, and of four of the smaller Powers, the latter being

chosen by the Assembly. Representatives of Belgium,

Brazil, Spain and Greece are to sit upon the Council until

others are selected by the Assembly.

Any member of the League, not represented on the

Council, is entitled to send a representative to sit at any

meeting of the Council during the consideration of matters

specially affecting the interests of that member. (Article 9).

Except where otherwise expressly provided, all decisions

of both Council and Assembly must be unanimous. (Article

Article 5).

Article 15 is, perhaps, the most important provision

making an exception to the general rule requiring unanimity.

This Article provides that the Council may make a report,

and if that report is unanimously agreed to by members,

other than the representatives of one or more of the parties

to the dispute, the members of the League agree that they

will not go to war with any party to the dispute which

complies with the recommendations of the report. It is

important to remember, however, that, as a general rule,

no decision is effective unless it is unanimous.

If Great Britain is not a party to a dispute in which

Australia is concerned, and if Great Britain supports the view

of Australia, a decision adverse to Australia will be impossible,

because there cannot be unanimity.

But if a complaint affecting Australia were made against

Great Britain instead of against Australia, interesting

questions would arise. It might be that Great Britain would

decline the role of defendant, and would apply for Australia

to be substituted. If this were done and Great Britain

supported us, it would be all in our favor. In any case, it

would be desirable for Australia to be the defendant,

because Australia could then have her own representative

on the Council, and would also have the benefits arising

from our relationship with Great Britain.

These considerations show how important it is that we

should seek to win the support of Great Britain in any

matters of foreign policy in which Australia may be

concerned.

But further, any one supporter, not necessarily Great

Britain, on the Council, would be sufficient to prevent an

adverse decision. Thus it is a matter of urgency for Australia

to make international friends. There is nothing in

our policy, when it is understood, which should offend other

peoples. The important thing is to get it known and to

get it understood. Take for example Spain, one of the

Powers now represented on the Council of the League. What

15

chance has anyone in Spain to understand Australian policy?

We must send some of our best men abroad to meet the

representatives of other countries. It will be necessary to

appoint a representative of Australia on the League of

Nations. This representative, if he is to do real and useful

work, must be on the other side of the world, though he

should strenuously avoid getting out of touch with Australian

opinion and feeling. He should be a man who thoroughly

understands and is in sympathy with Australian policy and

sentiment, and who can meet British Ministers and the

representatives of other nations upon an equality of intellectual

standing, though possibly not of experience in international

affairs. He should be capable of combining

“suaviter in modo” with “fortiter in re,” remembering

that in the arena of diplomacy the quiet man often wins the

greatest victories, and that only a discreet man can negotiate

successfully with those who are equal or superior to him in

power. It would be a mistake to send a representative who

was merely an office man. Some of the most important

work in the biggest affairs of the world is done, not at

formal meetings or conferences, but in a chat at a club or at

a dinner table. The important thing in many matters of

politics is to know the man intimately who has to deal with

the particular matter under consideration. A first class man

sent to London and Geneva could do most valuable work

for Australia.

Such a man, I suggest, should not be a civil servant

accustomed to departmental subordination. He should have

the status of a Minister, and might act as resident Minister

in London.

A member of Parliament, representing a constituency in

the Commonwealth Parliament, will not willingly, especially

if he is a real leader, spend a long period abroad. To do so

would be to risk losing his seat. It is, therefore, a question

for consideration whether a diplomatic representative of a

status approaching that of a Minister should not be specially

appointed for this work.

It will probably be suggested that the High Commissioner

should discharge these duties. I suggest that such an

arrangement would be a great mistake. The duties are so

important that they will require the whole time and attention

of the best man that Australia can get, and an active High

Commissioner will have plenty to do, especially if the

relations between the Commonwealth and the States with

respect to representation in London are readjusted so as to

remove some of the failures and inconveniences of the

existing system.

There is one outstanding matter which makes it of prime

16

importance to Australia that we should be effectively

represented on the League of Nations, and that immediate

arrangements should be made for the appointment of our

representative. Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of

Nations includes the following provision :

“The degree of authority, control, or administration to

be exercised by the mandatory shall, if not previously agreed

upon by members of the League, be explicitly defined in each

case by the Council."

Mr. Hughes has stated in the House of Representatives

that though the terms of the mandate to Australia are

practically arranged, the mandate has not been formally

granted. It therefore appears that the terms of the mandate

remain to be explicitly defined by the Council of the

League of Nations, and that the position is not secure until

this is done. Under Article 4 of the Covenant, Australia

will be entitled to send a representative to sit as a member

at any meeting of the Council at which the terms of the

Australian Mandate are to be discussed. It needs no

argument to demonstrate the necessity of the presence of a

competent Australian representative who should make it his

duty to meet other representatives before any formal

assembly is summoned.

REDUCTION OF ARMAMENTS.

Recurring to the Covenant of the League of Nations, l

call attention to Article 8, dealing with the reduction of

national armaments. There is a common but erroneous idea

that the Council of the League may order, for example, that

the British Navy should be reduced. This is not the case.

Article 8 of the Covenant provides that, in the first place,

the Council, “taking account of the geographical situation

and circumstances of each State, shall formulate plans” for

the reduction of armaments. In the second place, these

plans are submitted “for the consideration and action of the

several Governments.” The Article then goes on to provide

that “after these plans shall have been adopted by the

several Governments, the limits of armaments therein fixed

shall not be exceeded without the concurrence of the Council".

Thus, as action by the Council must be unanimous,

the British Government, as a member of the Council, must

concur in any plan for the reduction of the British Navy, and,

at a later stage, after considering the proposal, must adopt

it before the limitation can become effective. Thus, the

League of Nations, so far from being able to enforce a

reduction of armaments upon an unwilling country, merely

provides machinery for arriving at an agreement for reduction.

17

The machinery may prove to be ineffective, but it is

at least some advance upon the hopeless conditions which

have hitherto prevailed.

THE POWERS OF THE LEAGUE.

Article 10 is the Article round which so strenuous a fight

has been waged in America. As President Wilson has said,

it is the central provision of the Covenant. If Article 10

were struck out, the League would not be the institution

which was contemplated by the fourteenth of President

Wilson’s Fourteen Points.

The fourteenth point is in the following terms:—“A

general Association of Nations must be formed, under

specific covenants, for the purpose of affording mutual

guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity

to great and small States alike."

Article 10 of the Covenant is in these terms:—“The

members of the League undertake to respect and preserve,

as against external aggression, the territorial integrity and

existing political independence of all members of the League.

In case of any such aggression, or in case of any threat or

danger of such aggression, the Council shall advise upon the

means by which this obligation shall be fulfilled."

Observe the phrase “existing political independence."

This phrase makes it very difficult, if not impossible, for any

nation to found a complaint against another State upon any

policy which is now in operation under the laws of such

other State. For example, one of the incidents of the

existing political independence of Australia is to be found

in the legislation which carries out the policy of a White

Australia. Any requirement that Australia should limit her

powers in this respect, otherwise than by the will of the

Australian people, would certainly be an encroachment on

the existing political independence of Australia, which the

League is pledged to maintain.

It is true that under Article 2 and Article 19, almost any

subject might be brought before the Council of the League;

but it is then for the Council to determine whether it will

take any action, and the sphere of possible action of the

Council is limited by the various Articles of the Covenant.

One of such limitations is in Article 10. Another of them

is to be found in Article 15, which prohibits the Council from

making any recommendation in a dispute claimed by one of

the parties, and found by the Council, to arise out of a matter

which, by international law, is solely within the domestic

jurisdiction of that party.

Another common mistake about the League of Nations is

18

that the Council of the League would be able to order, e.g.,

Australian troops to go to a foreign country to fight. This

is a complete misapprehension. The Council, even in a case

under Article 10, can do no more than “advise upon the

means” whereby the obligations of the members shall be

fulfilled. Article 16, which provides the sanctions which

are to operate against any member of the League which, in

breach of its covenants, resorts to war, imposes obligations

only of a financial and economic character—that is, the

severance of trade or financial relations, and prohibition of

all intercourse with the nationals of the offending State,

whether financial, commercial or personal.

Article 12 of the Covenants records the agreement of the

members of the League, that if there should arise between

them any dispute likely to lead to a rupture, they will submit

the matter either to arbitration or to enquiry by the Council,

the members of the League in no case to resort to war until

three months after the award by the arbitrators or the report

by the Council.

By Article 13, the members of the League agree that they

will carry out in full good faith any award that may be made,

and that they will not resort to war against a member of

the League which complies with the award.

One of the most important clauses of the Covenant is

Article 15. This Article contains a scheme for the prevention

of international ruptures. In the case of a dispute likely to

lead to a rupture, which is not submitted to arbitration, the

members agree to submit it to the Council. They are to

forward a statement of their case, and the Council is to

endeavour to effect a settlement of the dispute. If it is not

settled, the Council, either unanimously or by a majority,

may make and publish a report of the facts and the

recommendations which are deemed just and proper. Any members

of the League have the right to make a public statement of

the facts of the dispute and of the conclusions of the Council.

The Article proceeds:—“If a report by the Council is

unanimously agreed to by the members thereof, other than

the representatives of one or more of the parties to the

dispute, the members of the League agree that they will not

go to war with any party to the dispute which complies with

the recommendations of the report.

Observe the effect of this. There is no agreement to go

to war, but only an agreement not to go to war with a State

which complies with the recommendation of the report. The

Council may, in any case, refer the dispute to the Assembly.

As a member of the Assembly, therefore, the representative

of Australia may have to deal with matters of vital

importance to the world,

19

LEAGUE OF NATIONS—SUMMARY.

The main points to which I suggest attention should be

paid, in connection with the League of Nations, are the

following :-

(1) Australia is given a full share in the work of the

League. There is, therefore, cast upon Australians

a responsibility and duty so to inform themselves

on international affairs as to be able to take

advantage of the opportunity which membership of

the League affords.

(2) The necessity of getting other nations to understand

our policy, so far as it touches foreign

relations, in order to extend the influence of

Australian ideas, and to increase our chances of

obtaining a sympathetic hearing should Australian

interests ever come up for discussion. We should

not wait until an issue is raised in a critical form

before seeking friends among the nations who will

see our policy from a sympathetic point of view.

(3) There is more need than ever for close co-operation

within the Empire. Hitherto there has been but

one spokesman in foreign affairs for the whole

Empire—the British Minister for Foreign Affairs.

We have kept our differences within our own

family. Now, however, there are several spokes-

men on the League of Nations for the different

parts of the Empire. Therefore, the need for

effective consultation between the various Dominions

and the United Kingdom is greater than ever.

Australia is one of the smaller nations and must have

friends in the world. We should make sure first of

unanimous support within the Empire. This can

be obtained only if we set this object deliberately

before ourselves, and use our best efforts to promote

understanding and to remove misunderstandings.

The consequences of a split upon policy between

the, various parts of the Empire would be much

more dangerous now than heretofore, because other

nations would be quick to take advantage of it,

and perhaps endeavour to play off one part of the

Empire against another.

(4) In Australia, we need a Department of Foreign

Affairs under, I suggest, the Prime Minister. If

this is not done, no Minister will be able to handle

foreign affairs in a really efficient manner. He must

have a competent staff, working continuously.

(5) We need to send at least one of our best men to

20

London and Geneva—a man who can speak for

Australia with ability, understanding, and discretion.

(6) The League of Nations will need much unofficial

help if it is to succeed. Some of the members of

the British and American staffs in Paris have

already taken action to provide reliable information

on international affairs for the League by establishing

the Institute of International Affairs. This is

work for men with expert knowledge and for

experts.

But much more than this must be done. In England

the League of Nations' Union has already done

much in England to familiarise the people with the

ideas and objects of the League, and it is to be

hoped that soon it will be possible to inaugurate

a similar organisation in Australia.

THE LABOUR COVENANT.

The Labour Covenant is an attempt to formulate a Charter

of Labour. Its objects may be shown by a quotation from

the preamble :-

“Whereas the League of Nations has for its object the

establishment of universal Peace, and such a Peace

can be established only if it is based upon social

justice :

“And whereas conditions of labour exist involving such

injustice, hardship and privation, to large numbers

of people as to produce unrest so great that the

peace and harmony of the world are imperilled, and

an improvement of these conditions is urgently required -

(here follow examples):

“Whereas also the failure of any nation to adopt humane

conditions of labour is an obstacle in the way of

other nations which desire to improve the conditions

in their, own countries :

“The High Contracting Parties, moved by sentiments of

justice and humanity, as well as by the desire to

secure the permanent peace of the world, agree to

the following Labour Covenant."

It is easy to decry these objects as Utopian and idealistic.

Anything in the nature of idealism is revolting to some types

of mind, but I venture to suggest that the hope of the world

lies with the men who are prepared to make their idealism

practical by applying it to such urgent problems as are

21

presented in all communities by the conditions of labour.

Australia is a member of the organisation set up by

Labour Covenant. This organisation consists of a general

conference of representatives of the members of the

International Labour Office. Australia is given the same

representation on the General Conference as all other Powers.

Each Government appoints four representatives, of whom

two are to be Government delegates, and the other two are

to be delegates representing employers and workpeople

respectively, to be nominated by the Governments in

agreement with the industrial organisations which are most

representative of employers or workpeople. Every delegate is

entitled to vote individually on all matters which are

considered at the Conference.

The International Labour Office is charged with the duties

of collecting and distributing information on all subjects

relating to the international adjustment of conditions of

industrial life and labour, and particularly of examining

subjects which it is proposed to bring before the Conference,

and of conducting special investigations as ordered by the

Conference.

The main provision of the Labour Covenant is to be found

in Article 40. This Article provides that the Conference may

either -

(a) Make a recommendation to be submitted to the

members for consideration, with a view to effect

being given to it by international legislation, or

(b) Submit a draft International Convention for

ratification by the members.

In either case, a majority of two-thirds is necessary on the

final vote for the adoption of the recommendation or draft

Convention.

THE OBLIGATION UNDERTAKEN.

The obligation undertaken by the members is that each

member will, within a year, or, at most, eighteen months,

"bring a recommendation or draft Convention before the

authority or authorities within whose competence the matter

lies, for the enactment of legislation or other action."

This is the only obligation which is undertaken, except

that, if the proposal is adopted, it is the duty of the nation

to carry it out. In the case of a nation first adopting a

proposal, and then failing to carry it out, an inquiry may be

held, and, if the complaint is found to be justified, other

members will be entitled to adopt measures of economic

boycott.

Article 405 includes the important general principle :-

22

"In no case shall any member be asked or required, as

the result of the adoption of any recommendation

or draft Convention by the Conference, to lessen

the protection afforded by its existing legislation to

the workers concerned."

Thus it will be seen that nothing which the Labour

Conference can do can, in any way, injure the position of the

workers of Australia. Further, though not believing that

everything is as good as it ought to be and might be, most

Australians are of opinion that, in Labour legislation,

Australia is in advance of any other country. That being so,

any action as the result of a recommendation by the Labour

Conference would, during an indefinite period, result only in

raising standards outside Australia. This is all to the advantage

of Australia.

The Labour Conference will afford Australians an opportunity

of bringing their methods of dealing with Labour

problems before the whole civilised world. If we are proud

of these methods, let us make them known and urge other

nations to adopt them. If we are not proud of them, it is

time that we discovered some methods of which we can be

proud.

OBJECTIONS TO THE LABOUR COVENANT.

It is interesting to see that in South Africa and Japan the

representatives of Labour selected by the Government do

not meet with the approval of some sections of the community,

and emphatic protests have been made in each case.

In Australia, the Labour organisations have declined to

nominate representatives, though afforded the opportunity.

The reason given in Australia appears to be that the Labour

Covenant is a dodge of the capitalist class, and that the

Prime Minister hides some dark political scheme behind his

request for the nomination of a representative.

This attitude is plainly the outcome of suspicion. The

Labour Covenant is there for all to read. No country can be

bound by anything that is done by the Labour Conference

until its own Government or Parliament decides to adopt

the proposal of the Conference. Therefore, no country, and

no section of a country, can be compromised by representatives

attending the Conference. All power is left in the

hands of the people of the country themselves. Further, the

Conference ought to be, if well controlled, a great educational

institution and a means of improving Labour conditions

throughout the world, apart altogether from the

formal recommendations of the Conference. Men of all

23

nations, and of greatly varying experience, will meet there

and discuss with one another the infinitely diverse problems

which arise. Finally, it should be remembered that all

representatives at the Conference vote individually.

So far, there is nothing very convincing in the objections

which certain Labour bodies have raised to a man chosen

by themselves attending the Labour Conference as a

representative of Labour. But behind these objections, and more

or less openly voiced, there is a more serious issue.

There are to be four representatives from each country,

two of them chosen by the Government, to represent the

Government ; the other two chosen by the Government, after

consultation with employers and workmen respectively. The

objection to sending representatives which has been voiced

in Australia makes, as a matter of course, the remarkable

assumption that representatives chosen by the

Government cannot represent the people. It is plain, however,

that the Government of a democratic country does, as

a general rule and over a period, in substance and as a

whole, represent the people. It is the only spokesman for

the people as a whole. But there is, to-day, a tendency to

refuse to admit that a Government can speak for a country

at all. The idea of the Government as representing the

community is going out of fashion in some quarters. So

long as the opposing political party is in power, the Government.

is regarded, not as an organ of the whole community,

but simply as a mechanism operated by a set of political

enemies. Hence arises an attitude of objection to the State

as such, and many schemes, more or less complete, are

proposed for substituting for the State, as we know it, a

system of society founded upon some form of combination

between the members of arbitrarily defined working classes.

This issue between a section of the people and the State

is the greatest issue of present day politics. It arises in part

from strained relations between the Government and a section

of the community owing to special war measures, and, in

Australia, it is also founded upon a profound general distrust

of the bona-fides of the Government, rather than upon

any definite political or social theory.

In the first place, it is important that the Government

should again win the confidence of the community as the

representative of the whole community, and as not consisting

merely of a dominant political party, aiming at its own

political objects. In the second place, Australia will not be

doing her duty in the new order of the world (if that order

ever becomes real), unless our people can regard some issues

as above party politics. A decision on a matter of vital and

equal importance to every citizen of Australia, whether man

24

or woman, adult or infant, should not be taken upon grounds

of the passing party politics of the day.

In no sphere of political activity is this principle of greater

importance than in relation to foreign policy. International

issues in which Australia is concerned should not be the

sport of local party politics. Within Australia, up to the

present, nearly all politics has been party politics. A larger

vision is needed to-day, and this larger vision must be the

vision of the people as a whole, and not merely the outlook

of a few officials or a few members of Parliament.

AUSTRALIA’S OPPORTUNITY.

What is required in Australia is a realisation of the vital

character of the issues which the new organisation of

international relations may force upon the attention of

Australians. It is to the interest of Australia to try to make

the League of Nations work, to try to make the Labour

Covenant work; but this will be done only if the public

opinion of Australia is mobilised and made effective.

That, after all, is the main thing behind the League of

Nations and the Labour Covenant. They are attempts to

mobilise the public opinion of the world—to get beyond the

views of the Chauvinists and the militarists, to re-establish

as against them the civilian ideal of nations living in peace

and reconciling their differences by recourse to reason rather

than by resort to war.

Australia can help to make these new proposals work if

the people only will that they shall work. Australia can lose

nothing by them, and stands to gain a great deal. We

believe that Australia can make contributions to human

well-being. If it be otherwise, Australian democracy has ceased

to be progressive in spirit and fertile in ideas. The opportunity

to help creates a duty to help. The position cannot

be better put than by one of the finest of all Australians,

Captain C. E. W. Bean:-

"In this generous competition within the League of

Nations there is no harm to any living thing. We

have to make our nation in the League of Nations

the best possible nation—our jewel in this ring of

jewels the brightest and most valuable jewel—our

counsel in the League the wisest and most generous

-our help the quickest, our word the straightest -

our name one which will have the respect of all the

rest.'

This is the duty, the task, and the opportunity which lies

before Australia in the new era opening to a war-worn

world.

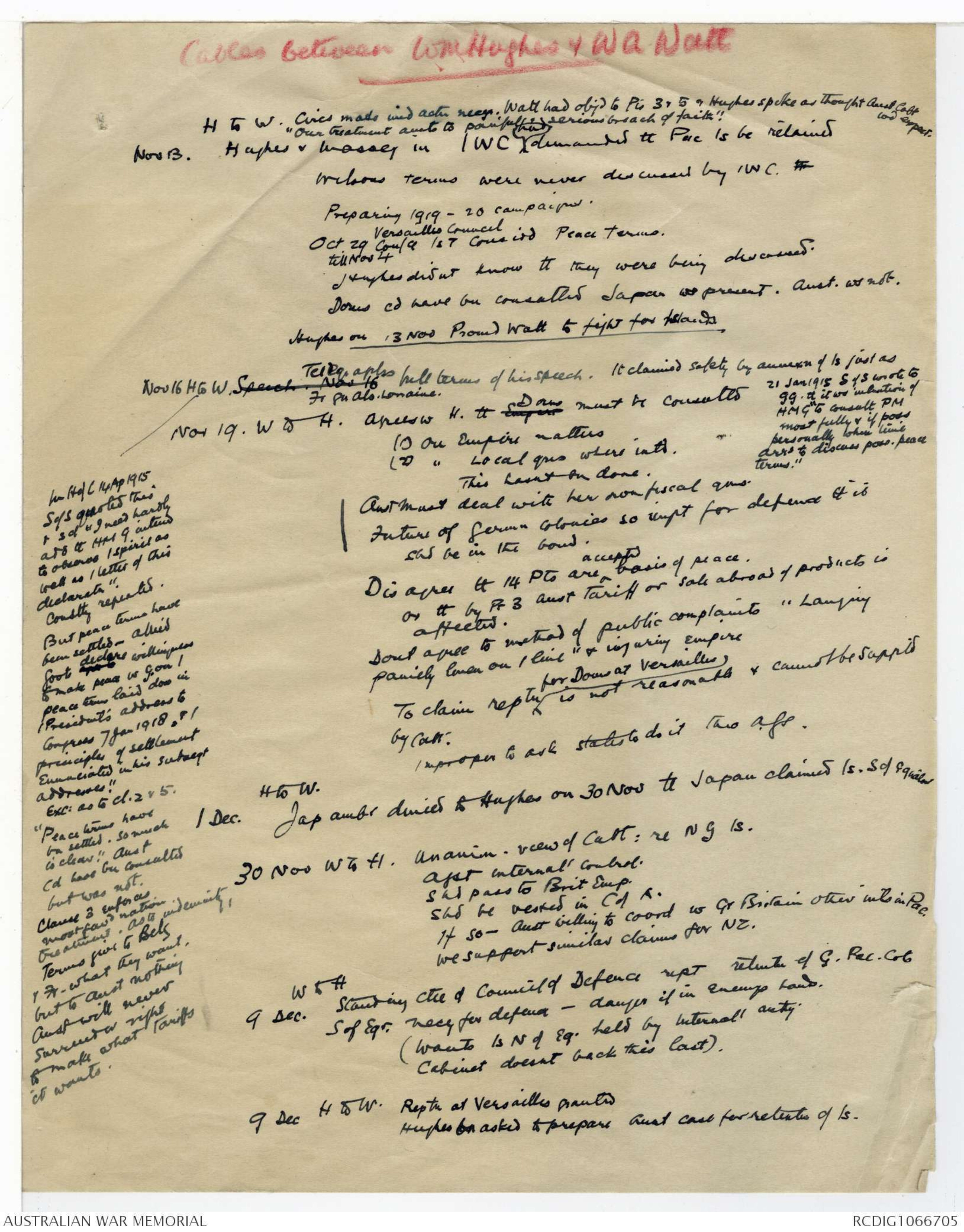

Cables between WM Hughes & W A Watt

H to W.

Circs made imd actn negs. Watt had obgd to Ps 3 & 5 & Hughes spoke as thought Aust Cabt wd expect.

"Our treatment amts to painful & serious breach of faith".

Nov 13

Hughes & Massey in IWC ^had demanded tt PAC Is to be retained

Wilson's terms were never discussed by IWC. xx

Preparing 1919 - 20 campaign.

Versailles Council

Oct 29 Con 8 1st considd Peace terms.

till Nov 4

Hughes didnt know tt they were being discussed.

Doms cd have bn consulted Japan ws present. Aust ws not.

Hughes on 13 Nov Promd Watt to fight for Islands

Nov 16 H to W. Speech Nov 16 Telegraphs full terms of his speech.

Fr gnals Lorraine

[*It claimed safety by annexn of Is just as

21 Jan 1915 S of E wrote to

GG tt it ws intention of

HMG "to consult PM

most fully & if poss

personally when time

arrg to discuss poss. peace

terms"*]

[* pen Hq C 14Ap 1915

S of S quoted this

& sd "I need hardly

add tt HM G intend

to observe / spirit as

well as / letter of this

declaratn".

Constly repeated.

But peace terms have

been settled w allied

Govt xxx declare willingness

to make peace with G. on /

peace terms laid done in

President's address to

Congress 7 Jan 1918, & /

principles of settlement

enunciated in his subsqt

address."

Exc: as to cl.2 & 5.

"Peace terms have

bn settled. So much

is clear." Aust

cd have bn consulted

but was not.

Clause 3 enforces

most favd nation

treatment. As to indemnity

Terms give to Belg

& what they want,

but to Aust nothing

Aust will never

surrender right

to make what tariffs

it wants.*]

Nov 19 W to H agrees w H tt Empire Doms must be consulted

10 on Empire matters.

20 "Local qns where intd.

This hasnt bn done.

Aust must deal with her non fiscal qns.

Future of German colonies so input for defence tt is

shd be in the bond

Disagree tt 14 Pts are ^accepted basis of peace.

or tt by Pt 3 Aus Tariff or sale abroad of products is

affected.

Dont agree to method of public complaints "Laying

Hanging family linen on / line " & injuring empire

To claim reptn ^for Dons at Versailles is not reasonable & cannot be supported

by Cabt.

Improper to ask states to do it this 'A.gs.'

1 Dec H to W Jap ambr denied to Hughes on 30 Nov tt Japan claimed Is S of Equator

30 Nov W to H Unamin. view of Cabt: re N G Is.

Agst internal control.

Shd pass to Brit Emp.

Shd be vested in C of A.

If so - Aust willing to co-ord w Gr Britain other inls in Pac.

we support similar claims for N.Z.

9 Dec. W to H Standing Ctee of Council of Defence rept retentn of G. Pac. Cols

S of Eqr. Necy for defence - danger if in Enemys hands.

(wants Is N of Eq. held by internatl authy.

Cabinet doesnt back this last).

9 Dec H to W Reptn at Versailles granted

Hughes bn asked to prepare Aust case for retentn of Is.

Sam scott

Sam scottThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.