Charles E W Bean, Diaries, AWM38 3DRL 606/269/1 - 1918 - 1936 - Part 1

AWM38

Official History,

1914-18 War: Records of C E W Bean,

Official Historian.

Diaries and Notebooks

Item number: 3DRL606/269/1

Title: Folder, 1918 - 1936

Covers the 1919 Paris Peace Conference and

the Reparations Commission and includes notes

by Bean, cables between WM Hughes and WA

Watt and letters from Sir John Latham and

Clement Jones.

AWM38-3DRL606/269/1

PEACE CONFERENCE. NO.269

1ST SET. AWM38 3DRL606 ITEM 269[1]

DIARIES AND NOTES OF C. E. W. BEAN

CONCERNING THE WAR OF 1914-1918

THE use of these diaries and notes is subject to conditions laid down in the terms

of gift to the Australian War Memorial. But, apart from those terms, I wish the

following circumstances and considerations to be brought to the notice of every

reader and writer who may use them.

These writings represent only what at the moment of making them I believed to be

true. The diaries were jotted down almost daily with the object of recording what

was then in the writer’'s mind. Often he wrote them when very tired and half asleep;

also, not infrequently, what he believed to be true was not so —but it does not

follow that he always discovered this, or remembered to correct the mistakes when

discovered. Indeed, he could not always remember that he had written them.

These records should, therefore, be used with great caution, as relating only what

their author, at the time of writing, believed. Further, he cannot, of course, vouch

for the accuracy of statements made to him by others and here recorded. But he

did try to ensure such accuracy by consulting, as far as possible, those who had

seen or otherwise taken part in the events. The constant falsity of second-hand

evidence (on which a large proportion of war stories are founded) was impressed

upon him by the second or third day of the Gallipoli campaign, notwithstanding that

those who passed on such stories usually themselves believed them to be true. All

second-hand evidence herein should be read with this in mind.

AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL

16 Sept, 1946. AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL ACCESS STATUS OPEN C.E.W. BEAN.

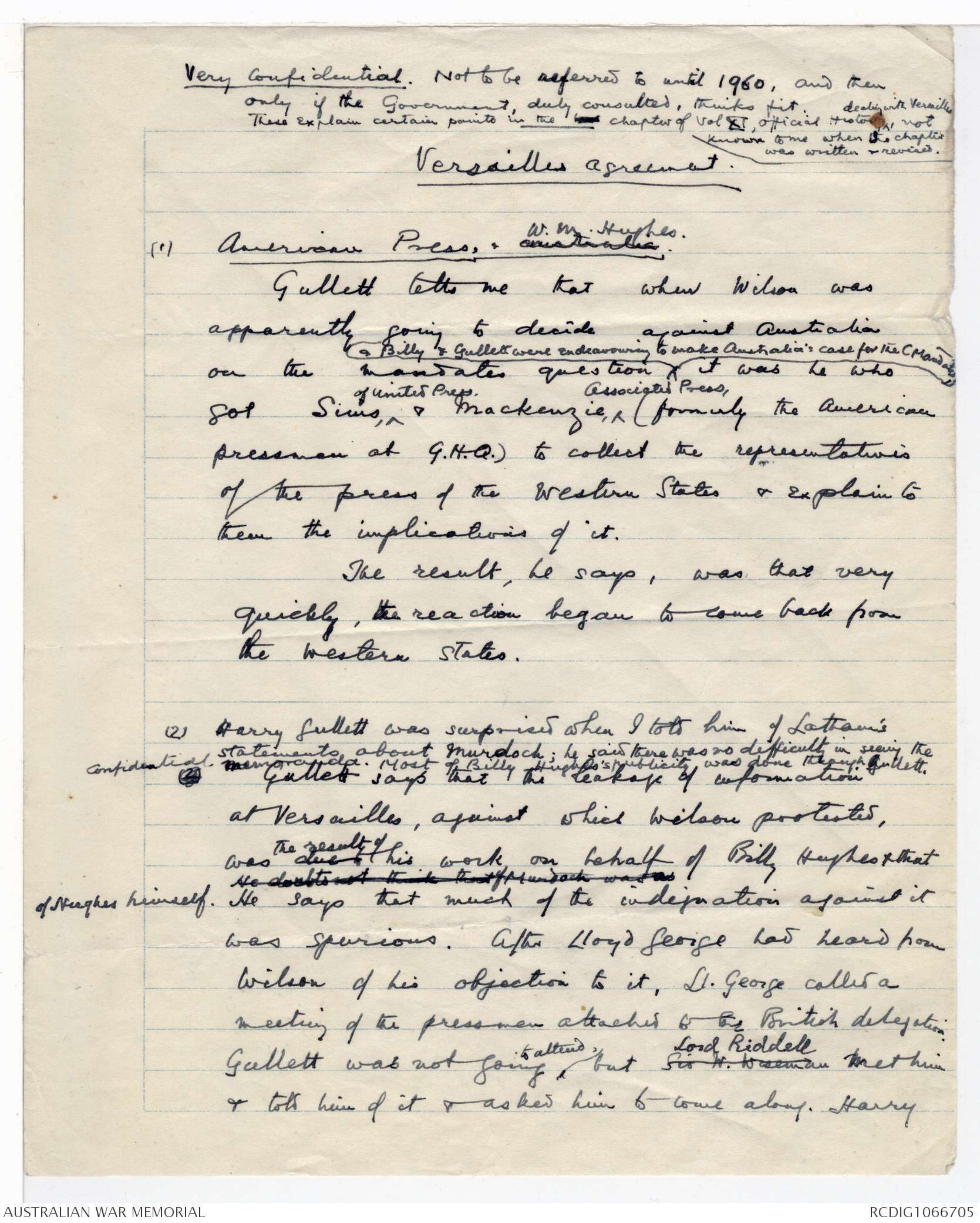

Very confidential. Not to be referred to until 1960, and then

only if the Government, duly consulted, thinks fit.

These explain certain points in the [[last?]] Chapter of Vol [[XI ?]], official Histo?]] dealing with Versailles not known to me when the chapter

was written & [[reviewed?]].

Versailles agreement.

(1) American Press, & [[ illegible?]] W. M. Hughes.

Gullett telts me that when Wilson was

apparently going to decide against Australia

on the [[mandates?]] question

(& Billy & Gullett were endeavouring to make Australia's case for the C Mandates,)

it was he who

got Sims, of United Press & Mackenzie, Associated Press (formerly the American

pressman at G.H.Q.) to collect the representatives

of the press of the Western States & explain to

them the implications of it.

The result, he says, was that very

quickly, the reaction began to come back from

the Western States.

(2) Harry [[Gullett?]] was surprised when I told him of Latham's

statements, about Murdoch; he said there was no difficulty in seeing the

[*confidential*] memoranda. Most of Billy Hughes's publicity was done [[through?]] Gullett.

Gullett says that the leakage of information

at Versailles, against which Wilson [protects?]],

was due the result of his work on behalf of Billy Hughes & that

of Hughes himself. He doubts not think that of Murdoch [[wasnt?]]

He says that much of the [[indignation?]] against it

was spurious. After Lloyd George had heard from

Wilson of his objection to it, [[Lt.?]] George called a

meeting of the pressmen attached to [[the?]] British delegation.

to attend

Lord Riddell

Gallett was not going but Sir W. Wiseman met him

& told him of it & asked him to tome along. Harry

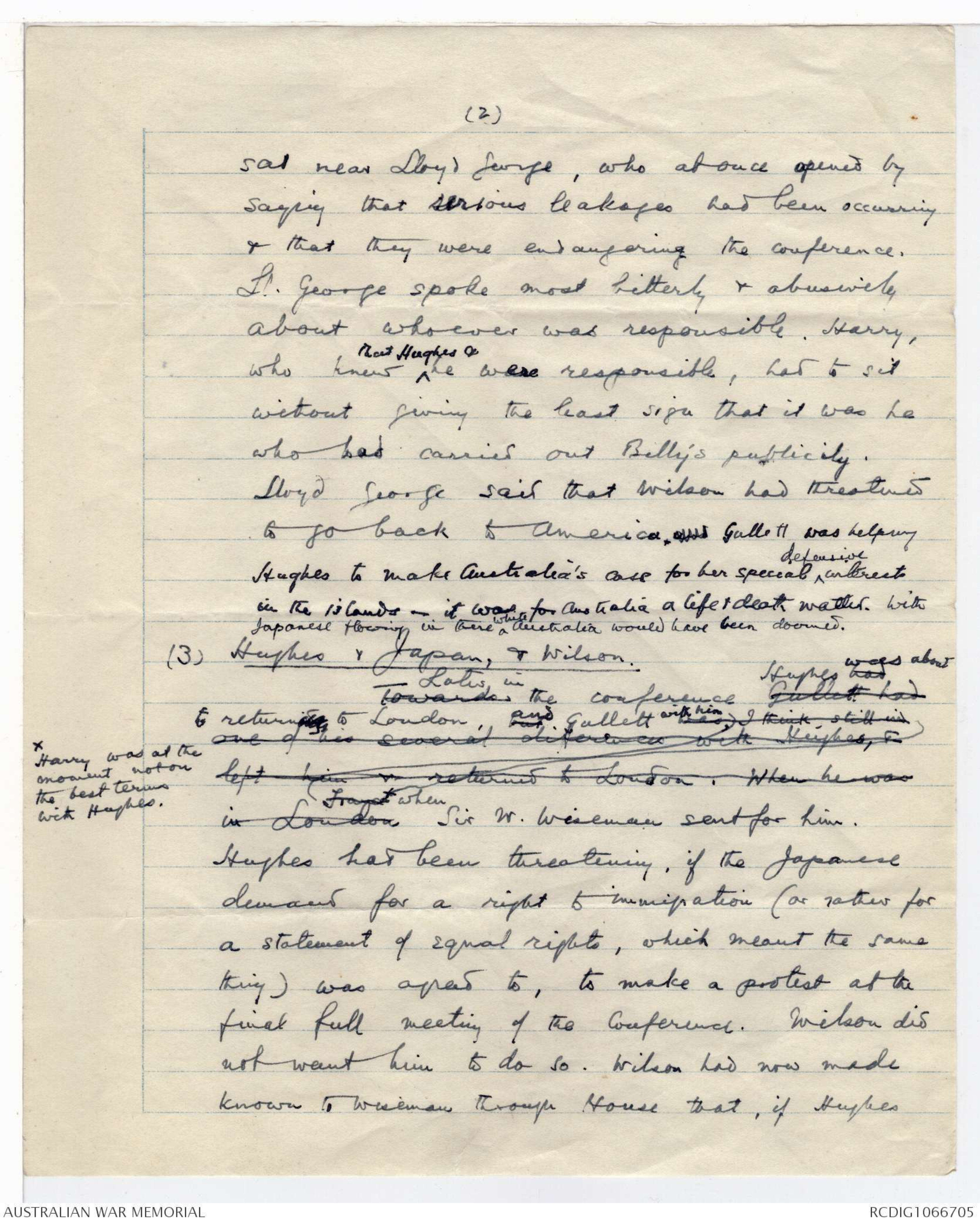

(2)

sat near Lloyd George, who at once opened by

sagny that serious leakages had been occurring

& that they were endangering the conference.

L. George spoke most bitterly & abusively

about whoever was responsible. Harry,

who knew that Hughes & he were responsible, had to sit

witout giving the last sign that it was he

who has carries out Billy's publicity.

Lloyd George said that Wilson had threatened

to go back to America. And Gallett was helping

Hughes to make Australia's case for her special defensive interest

in the islands [[&?]] it was for Anstialia a life & death matter. With

Japanest [[flowing?]] in there while Australia would have been doomed.

(3) Hughes & Japan, & Wilson.Towards Later in the conference Hughes was was about

to returning to London, and Gullett with him has, I think, still in

[*Harry was at the moment not on the best terms with Hughes*]

one of his several [[differences?]] with Hughes, &

left him and returned to London. When he was inLondon France when Sir W. Wiseman sent for him.

Hughes has been threatening, if the Japanese

demand for a right to [[immigration?]] ( or rather for

a statement of equal rights, which meant the same

thing) was agreed to, to make a protest at the

final full meeting of the Conference. Wilson did

not want him to do so. Wilson had now made

known to Wiseman through House that, if Hughes

(3)

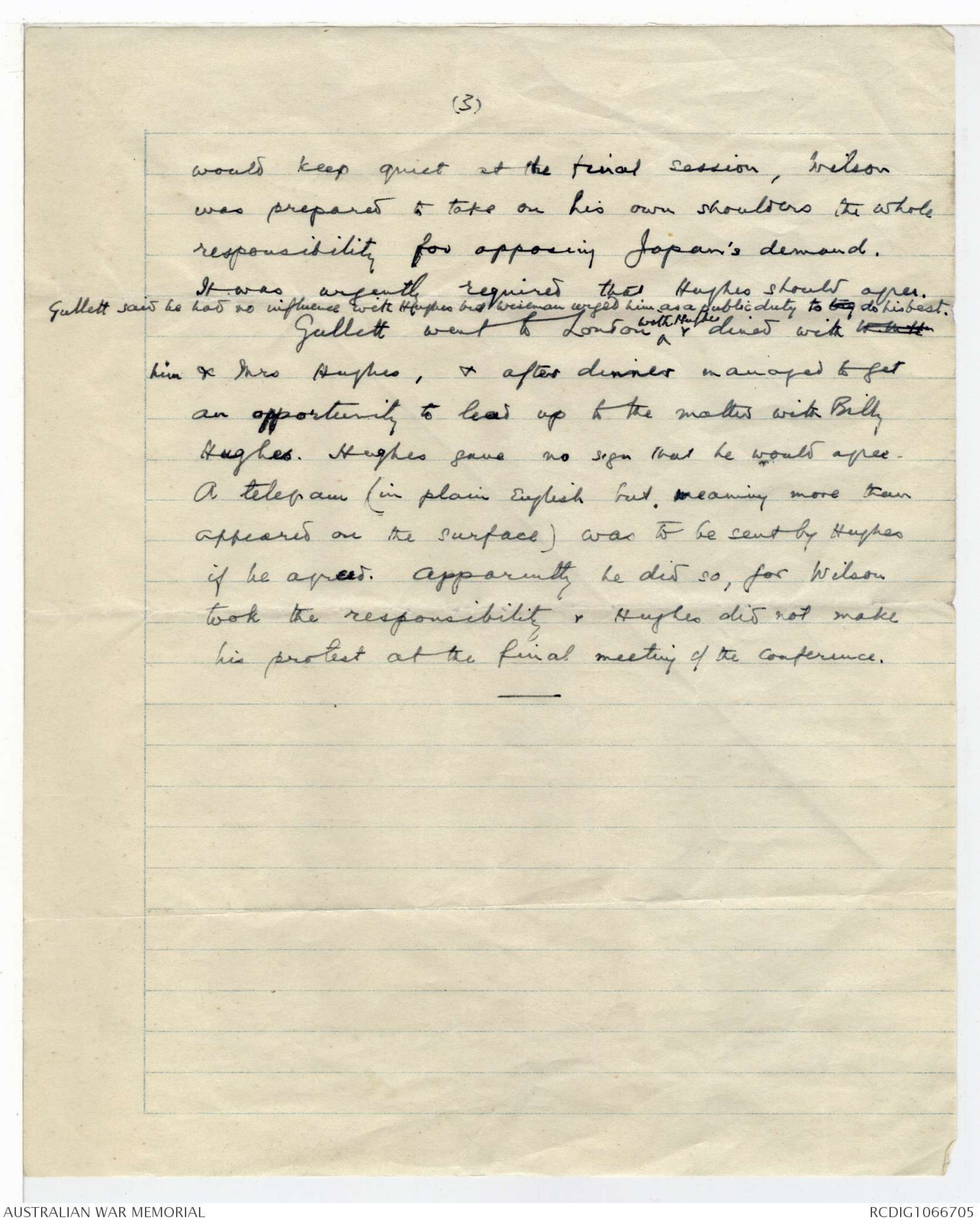

would keep quiet at the final session, Wilson

was prepared 5 take on his own shoulders the whole

responsibility for opposing Japan's demand.

It was urgently that Hughes should agree.

Gullett saw he had no influence with Hughes but Wiseman urged him as a public duty to beg do his best.

Gullett went to London with Hughes and dined with [[W.Weston?]]

him & Mrs Hughes, & after dinner managed to get

an opportunity to lead up to the matter with Billy

Hughes. Hughes gave no sign that he would agree.

A telegam (in plain English but meaning more than

appeared on the surface) was to be sent by Hughes

if he agreed. Apparently he did so, for Wilson

took the responsibility & Huyles did not make

his protest at the final meeting of the conference.

THE SIGNIFICANCE

OF THE

PEACE CONFERENCE

FROM AN

AUSTRALIAN POINT OF VIEW

BY

J.G. LATHAM PRICE 6p

THE SIGNIFICANCE

OF THE

PEACE CONFERENCE

FROM AN

AUSTRALLAN POINT OF VIEW

BY

J. G. LATHAM

MELVILLE & MULLEN PTY. LTD,

1920

THE SIGNIFICANCE

OF

THE PEACE CONFERENCE

FROM

An Australian Point of View

An Address delivered before the Melbourne University

Association on 23rd October, 1919, by Lieutenant-

Commander J. G. Latham, C.M.G., R.A.N.R. (Member

of the Australian Delegation at the Peace Conference;

Assistant Secretary of the British Empire Delegation;

British Secretary of the Inter-Allied Commission on

Czecho-Slovak Affairs).

It is not always realised in Australia that the Peace

Treaty marks much more than the end of the war.

It is often said that the war has given Australia a new

status, and that this status is recognised in the Treaty of

Peace. But the nature and significance of the change of

status have not yet been worked out, and but little attention

has been devoted to the questions involved. The enhanced

status which Australia has undoubtedly gained means a

great deal more than an international compliment. When

an infant comes of age he acquires new responsibilities and

new duties and new risks. So it is with Australia. Aus-

tralia has won nationhood—and nationhood brings respon-

sibilities, duties and risks, as well as benefits and advan-

tages. The benefits and advantages are of the same general

character as in the case of an infant attaining his majority.

Australia has now an opportunity of taking a greater share

in the moulding of her own destiny. In the past Australia

has had no self-conscious foreign policy, and the foreign

affairs which concerned Australia were dealt with by the

Imperial Government.

Now that Australia is to have a

larger share in the handling of this important and, indeed,

4

vital subject, she will need all the ability and wisdom of her

people. It is my object to indicate some of the new respon-

sibilities and duties which have fallen upon Australia, to

say something of the stages in the evolution of our new

national status, and to make some suggestions as to the

means whereby these responsibilities may be fulfilled, and

these duties discharged, in a manner worthy of our country.

THE ARMISTICE.

The hands of the plenipotentaries at Paris were not free-

they did not have a clean sheet of paper upon which to

write. They had already set their hands to President

Wilson's Fourteen Points. They had accepted the fourteen

points, with two exceptions, and certain of President Wil-

son's speeches, as defining the principles upon which peace

was to be made with Germany. We had explicitly agreed

that these terms were not merely a basis for negotiation, but

that all that remained to be dealt with at the Peace Con-

ference was their practical application. It is necessary to

bear this in mind when criticising some of the decisions of

the Conference. The delegates were not free, and they were

not free because they had already bound themselves in the

most solemn manner.

It will be remembered that in November, 1918, as soon as

the armistice was announced, Mr. Hughes addressed a

meeting in London, at which he protested most vigorously

against the action of the British Government in consenting

to the armistice, including as it did the Fourteen Points,

without consuiting the Dominions. This protest gained

little or no support at the time, either in Australia, the

other Dominions, or in Great Britain. The complacency

with which the people of the Dominions accepted the posi-

tion was, I think, due to the common belief that the armis-

tice dealt only with naval and military subjects, and had

nothing to do with the final terms of peace..

This was a misunderstanding. The armistice not only

dealt with matters affecting the navies, armies and air ser-

vices of the belligerents, but also limited the freedom of

action of the delegates to the Peace Conference in regard to

many material and, indeed, vital matters. The essential

thing to remember about the fourteen points is that they

were, in every relevant sense, terms of peace. The Allies'

acceptance of the Fourteen Points was communicated to Pre-

sident Wilson in a Note, which, on November 5, he, in turn,

communicated to the Germans. The following is the most

important passage of this Note:-

"Subject to the qualifications which follow, the Allied

5

Governments declare their willingness to make peace

with the Government of Germany on the terms of peace

laid down in the President’s address to Congress on

January 8, 1918, and the principles of settlement

enunciated in his subsequent addresses."

One of the modifications made by the Allies related to the

freedom of the seas, upon which all rights were reserved.

Thus this subject did not come up for discussion at the Con-

terence.

REPARATIONS.

The other modification related to reparations. In some

very awkward phrasing the Allies stated that they under

stood that the points which dealt with restoration should be

interpreted in a particular way. In fact, the subject of

restoration was mentioned in connection only with Belgium,

France, Roumania, Serbia and Montenegro, but the Allies'

gloss upon the word "restoration" was in the following

terms:-

"Further in the conditions of peace laid down in his

address to Congress on January 8, 1918, the President

declared that the invaded territories must be restored as

well as evacuated and freed, and the Allied Govern-

ments feel that no doubt should be allowed to exist as

to what this provision implies. By it they understand

that compensation will be made by Germany for all

damage done to civilian populations and the loss of their

property by the aggression of Germany by land, by sea,

or from the air."

Thus it will be seen that the Allies were not content with

the limited demands for what President Wilson called restora-

tion; they insisted upon extending it to cover damage done

to the civilian population of the Allies and their property-

but they went no further. That is, they made a limited claim

for indemnities, and there is no real room for doubt that in

so doing they abandoned, and knew that they abandoned,

any claim for the full costs of the war. That this was the

case was most clearly and convincingly pointed out by Mr.

Hughes in his speech in November.

The fact that Australia has to bear her own war debt is

therefore explained by the terms of the Fourteen Points, as

modified by the Allies. Though much discussion took place

at the Peace Conference upon the obligation of Germany to

make reparation, and though vigorous efforts were made to

charge Germany with the full cost of the war, the question

was really settled by the terms of the armistice.

The Peace Treaty recognises ten categories of damage

which Germany has to make good. The only head under

6

which Australia will be able to claim any substantial amount

is that of pensions to mutilated, wounded or sick, and to

their dependants, and allowances to the families and depen-

dants of persons serving with the forces. The pensions and

allowances are to be calculated on the basis of the scales in

force in France.

THE REPRESENTATION OF THE DOMINIONS AT

THE PEACE CONFERENCE.

Mr. Lloyd George succeeded in persuading the other

Allied leaders to concede separate representation at the Peace

Conference to the Dominions and India. Some idea of the

difficulties which he had to overcome may be obtained from

a consideration of the discussion now proceeding in America

upon the subject of the representation of the Dominions on

the League of Nations. France, Italy and the United

States were to have only five representatives each on the

Conference. The admission of the claims of the Dominions

and India to separate representation meant that the British

Empire had in all fourteen representatives. That Mr. Lloyd

George succeeded in gaining his point is an illustration of

that remarkable skill in negotiation for which the future

will assuredly give him full credit.

If the actual result of separate representation at the

Peace Conference had been what most people would have

considered was its logical effect, the result would have been

most serious. If the Dominions had, in fact, assumed a

separateness from Great Britain of the same character as

that, say, of Roumania or Brazil, which also had separate

representation, it is clear that the Empire would have

ceased to exist as a single and united Empire. But the

logical result was, as is often the case with our race, not

the actual result. In the first place, after the press had wor

its fight for admission to the proceedings of the Peace Con-

ference, it soon became apparent that the position at the

actual meetings of the Conference would have been much

the same if the Dominions had had 20 representatives each

instead of two or one (as in the case of New Zealand). The

The proceedings at these meetings were invariably and

necessarily prearranged and formal, except on one occasion,

when the interests of the Dominions were not specially

affected. In the second place, it would have been difficult

for the Dominion representatives to complain if the Imperial

Ministers had said, "You wish to be separate; then be

separate, and we will work apart." If the Dominions had

been put into this position they would not have had access

to the documents of the British Delegation, they would not

7

have had the benefit of consultation with British Ministers,

and they would not have enjoyed the services of the British

Staff. They would have been as separate and distinct as

Uruguay or Siam, though they might have been more in-

fuential than Uruguay or Siam.

What happened was not at all logical. The Dominions

received the benefits of separate representation and at the

same time the benefits of union between themselves and the

rest of the Empire. The representatives consulted in Cabi-

net with British and other Dominion Ministers, and had the

full benefit of the diplomatic and other knowledge of the

Foreign Office, and of the great Imperial Departments.

Further, the case for the Dominions was put not only by

themselves, but also by the British representatives. Mr.

Lloyd George, in the meetings of the Big Four, was able

to speak on behalf of the Dominions as well as on behalf of

Great Britain. Mr. Balfour was in the same position in

the Council of Foreign Ministers. In addition to this, the

Dominions, in relation to matters particularly affecting

themselves, were regarded as "nations with special inte-

rests," and were admitted to what were called the Informal

Conventions at the Quai d'Orsay, and were given the oppor-

tunity of putting their own case. This happened when the

destiny of the German colonies was under discussion. Thus

the significance of separate representation was, in practice,

not as great as at first sight it appeared to be.

Reference to the actual Treaty will show that the unity

of the Empire is recognised in the form of signature. The

party to the Treaty is-

HIS MAJESTY THE KING,

by Rt. Hon. DAVID LLOYD-GEORGE, M.P.

(and four other Imperial Ministers).

And for the DOMINION OF CANADA,

by SIR ROBERT BORDEN,

SIR GEORGE FOSTER.

For the COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA,

by RT. HON. WILLLAM MORRIS HUGHES

RT. HON. SIR JOSEPH COOK,

etc., etc.,

Thus there is but one party to the Treaty on behalf of the

whole Empire—the King.

The continued unity of the Empire is also recog-

nised in the ratification of the treaty which has just

taken place. The Treaty has been submitted to the Parlia-

Sam scott

Sam scottThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.