Charles E W Bean, Diaries, AWM38 3DRL 606/264/1 - 1914 - 1938 - Part 1

AWM38

Official History,

1914-18 War: Records of C E W Bean,

Official Historian.

Diaries and Notebooks

ltem number: 3DRL606/264/1

Title: Folder, 1914 - 1938

Covers the RAN reserves, the WOLF, the

SYDNEY - EMDEN engagement and the

submarine, "AE1"; includes Bean’s notes,

cuttings and letters from W A Newman, Arthur C

Newton, Cmdr C A Parker and Cmdr R C Garcia.

AWM38-3DRL606/264/1

1st SET. R.A.N., etc. No. 264

AWM38 3DRL 606 ITEM [[?]]

DIARIES AND NOTES OF C. E. W. BEAN

CONCERNING THE WAR OF 1914 - 1918

THE use of these diaries and notes is subject to conditions laid down in the terms

of gift to the Australian War Memorial. But, apart from those terms, I wish the

following circumstances and considerations to be brought to the notice of every

reader and writer who may use them.

These writings represent only what at the moment of making them I believed to be

true. The diaries were jotted down almost daily with the object of recording what

was then in the writer's mind. Often he wrote them when very tired and half asleep;

also, not infrequently, what he believed to be true was not so — but it does not

follow that he always discovered this, or remembered to correct the mistakes when

discovered. Indeed, he could not always remember that he had written them.

These records should, therefore, be used with great caution, as relating only what

their author, at the time of writing, believed. Further, he cannot, of course, vouch

for the accuracy of statements made to him by others and here recorded. But he

did try to ensure such accuracy by consulting, as far as possible, those who had

seen or otherwise taken part in the events. The constant falsity of second-hand

evidence (on which a large proportion of war stories are founded) was impressed

upon him by the second or third day of the Gallipoli campaign, notwithstanding that

those who passed on such stories usually themselves believed them to be true. All

second-hand evidence herein should be read with this in mind.

16 Sept., 1946. C. E. W. BEAN.

[*Sydney Morning Herald

29/12/37*]

WRECK OF EMDEN

RIFLED.

Japanese Ship Seized.

30 TONS OF METAL ABOARD.

SINGAPORE, Dec. 28.

The marine police to-day seized the

Japanese-owned fishing vessel Anyo

Maru when it arrived here. A search

revealed 30 tons of bronze and other

metal salvaged from the wreck of the

German cruiser Emden at the Cocos

Islands.

It was the same vessel which brought some

unexploded shells to Singapore in October.

The Emden was damaged and was run

ashore at the Cocos Islands in 1914 during an

engagement with the Australian cruiser

Sydney.

[*S.M. Herald

14/10/37*]

TINGIRA SOLD.

To Be Resold to

Former Owners.

FAMOUS TRAINING SHIP.

The former training ship Tingira,

once, as the Sobraon, the pride of the

Australian merchant marine, was sold

at auction yesterday to satisfy a debt

incurred under a bill of sale, but it was

learned last night that the purchaser

had agreed to sell the ship back to the

former owners.

The vessel was sold by order of the

mortgagee, Mr. Adam Aberline, and was

bought for £1050 by Mr. K. Silvinen, demolition

contractor, of Balmain. It was to have

been sold last week, but the sale was prevented

then by an injunction granted to the

owners, Mr. Sydney Friere and Mrs. Louisa

Ankin.

Mr. Friere, on behalf of himself and Mrs.

Louisa Ankin, stated last night that Mr.

Silvinen had agreed to sell the Tingira back

to them at a small profit.

Mr. Friere said that they could have raised

sufficient money to wipe off the mortgage if

they had had a little more time. They had

invested about £6000 in the ship, and their

main object had been to save the vessel from

demolition.

It was a bleak scene when the little party

gathered on the after-deck of the Tingira

yesterday as she lay in Berry's Bay, and the

auctioneer (Mr. K. W. Huenerbein, of F. R.

Strange, Ltd.) mounted a companionway to

call for bids.

At least three of those present—Captains

Selwyn Day and T. W. Arthur, and Mr. S. S.

Dodgson, who had served in the old Sobraon

—must have felt the contrast bitterly. The

Tingira they boarded yesterday was a rusty

hulk, her gold scroll-work tarnished, her

white paint flaked, and weeds thick on her

keel. Portholes with broken windows gaped

forlornly, and the wind rattled frayed shrouds

and ratlines.

The auctioneer used a historic gavel presented

to him for the purpose by Captain

Arthur. Its head was of teak from the Foudroyant,

Nelson's flagship at the Battle of the

Nile, and its handle of teak from the famous

Victory. Bidding began at £200, and advanced

by £50 rises to £1050, when the

vessel was "knocked down."

Last week the Chief Judge in Equity adjourned

until yesterday an application to

restrain Mr. Aberline from offering the ship

for sale. On the matter being called yesterday

the only order asked for was dismissal of

the summons with leave to the mortgagee to

add costs to the mortgage debt.

[*HN*]

Such is war at sea—

Hell on the “Emden"

Condensed from Liberty

Rear Admiral Robert Witthoeft

of the German Navy

As told to Wayne Francis Palmer

The German cruiser Emden was

the terror of the Pacific and Indian

Oceans during the early months of

the World War. Operating alone and

without a base, and with half the

world against her, she harried Allied

shipping in one of the most daring sea

raids of all time. Starting from China,

where she was stationed when war

was declared in August, 1914, the

Emden blocked the transportation of

Anzac troops to France, shelled

British oil reserves at Madras, and

sank some $15,000,000 worth of

shipping, after first removing non-combatant

crews. In one typical raid

she crept at dawn into the harbor of

Penang and blew up a Russian

cruiser with a sudden hail of shells

that gave the doomed crew not

even a chance to fight. But on November

9, 1914, she was surprised in

turn. While putting a landing party

ashore to destroy a British cable

station on Direction Island, Captain

von Müller of the Emden sighted a

hostile cruiser approaching. One of

the Emden's officers here describes

what followed.

THE BUGLE BLARED. There was

the tramping of feet as men

rushed to their battle stations.

Gun breeches banged. Then order

and silence reigned as the Emden

steamed out to meet the enemy.

It looks like the Newcastle,"

said the captain as he squinted

through the slit in the conning

tower. “That’s not so bad. She

may have a little more gun power

than we - but l’ve got the Emden’s

crew! Full speed ahead."

We were the first to open fire,

at about 10,000 yards, on a

course parallel with the mysterious

British cruiser. Our third

salvo struck her upper works and

sent up a cloud of black smoke.

“First blood!” Gunnery Officer

Gaede yelled. “We’ve got their

range. Now let them have it."

Meanwhile, there was a flash

of orange flame from the other

ship as they gave us their broadside.

We could actually pick up

the shells as they came toward us,

looking like so many bluebottle

flies. They seemed to waver as

they neared, and then we lost

them as they moaned over us.

Soon, however, great geysers began

rising out of the sea so close

© 1935, Liberty Pub. Corp., 1926 Broadway, N. Y. C.

(Liberty, August 24, ’35)

49

[*U.S.A.*]

50 THE READER’S DIGEST October

to us that they brought tons of

water crashing down on our deck.

"We’re in for trouble," Captain

von Müller said quietly.

“Those splashes are from a much

heavier ship than I had thought."

He turned to the navigating officer.

"Closer, Gropius, closer," he

ordered.

And the Emden edged over

toward the enemy to reduce the

range. Under the clouds of yellowish

smoke that billowed above

her I saw our shells striking home

time after time; but meanwhile

her shots were getting uncomfortably

near us. Then with a crash

the first shell came aboard us and

burst in the wireless cabin. Instantly

nothing was left but its

twisted white-hot steel frame.

Our faithful operators, who had

for so long been our only link

with the outside world, were

destroyed.

Immediately thereafter a shell

burst with an appalling noise

directly in front of the conning

tower. For the next few seconds

everything was strangely silent.

We missed the rapid bark of the

forward gun, but in its place

came the groaning of the wounded

and dying. It was a frightful

mess out there. Gaede called up a

reserve crew; and the captain

repeated his order: "Closer, Gropius,

closer!"

But already we knew that we

did not have a chance. They

would run out as we tried to close

in, and then with their longer

range guns they would pound us

unmercifully. The battle became

a nightmare to me. Lieutenant

Zimmerman, seeing that there

was more trouble with the forecastle

gun, dashed forward from

the conning tower. Just as he

arrived an explosion killed him

and every man at the gun. That

same shell got the captain and

myself, but only slightly.

The forward smokestack was

hit and collapsed. The foremast

came down and slid off into the

sea, carrying with it the foremast

crew. Gropius dashed aft to see

what was wrong with the rudder.

There was now a slackening in

our rate of gunfire, and Gaede

left the conning tower to find out

why. He hadn't gone far before a

shell splinter got him, and he fell

dying to the deck, his white

uniform drenched with blood.

Our two remaining stacks were

hit and took a cockeyed tilt.

Suddenly there was a ghastly

concussion somewhere amidships

as the deck folded up and buckled.

A broadside gun hurtled up into

the air. Men, steel plates, mess

benches, and great splinters could

be seen in the flying mass of debris.

Everything seemed on fire at

once.

Gropius was caught aft with

the few survivors from the poop

gun. Intent on what they were

doing, they didn't notice that the

flames were eating their way aft

1935 HELL ON THE "EMDEN" 51

until a solid wall of fire confronted

them. They tried to

break through by going to a lower

deck, but down there it was like

some terrible furnace. Step by

step they were forced to retreat

until they were huddled together

on the very stern. Swiftly the

flames rushed at them; they knew

the end was at hand. Gropius led

three cheers for our Fatherland.

But before they had finished a

shell hit near by and they were

all blown overboard.

Up in the conning tower Captain

von Müller and I were now

alone. Our guns were silent; our

ammunition exhausted. Our ship

was without a rudder. “It’s no

use going on, Witthoeft,” the

captain said. "This is nothing but

slaughter. I must save what men

I can, and yet I won’t let them

have my ship. See, there is North

Keeling Island dead ahead. l’m

going to try to put her there high

and dry".

While the British fairly poured

their shells into us, we rushed full

speed for the beach. We signaled

the engine-room force to climb to

safety. With a tearing impact the

Emden slipped in between two

large coral reefs and there, about

100 yards offshore, our ship came

to rest, a burning, sinking charnel

house. Our cruise was ended.

Captain von Müller told those

of us who had collected around

him on the upper deck that we

might try to swim ashore if we

wished. A few tried but only five

of them reached the beach. The

others were crushed on the reef.

The captain ordered all survivors

up to the comparative

safety of the forecastle. Half the

officers were dead. The deck and

gun crews were almost entirely

wiped out. The engine-room and

fire-room crews now made up

most of our little band.

Some of us went below to look

for the wounded. Of all the

experiences of my life, that was the

most ghastly and crushing. Here

and there a single candle spluttered,

but it only added to the

horror. The stench of burning

hammocks and burned human

flesh nauseated us. Bodies, or

what had been bodies, lay strewn

about the guns and in the

passageways. The mutilation of the

dead was beyond belief. All was

silent below decks, excepting the

steady muffled roar and crackling

of the flames.

On the forecastle the condition

of the wounded was pitiful. They

cried for water, but the tanks had

been shot away. As though our

afflictions were not enough, a

number of vicious sea birds settled

down on the deck. As we left

one helpless wounded man to go

to another, they would rush at

him and tear at his eyes or at his

wounds. We tried to beat them

back with clubs. Never having

seen any men before, they were

without fear of us.

52 THE READER’S DIGEST

Our situation was becoming

unbearable and the shore seemed

such a little way to go - only 300

feet. Our boats had been blown to

bits or burned. We tried floating

light lines attached to boxes to

the men who had reached shore,

but every attempt failed.

Meanwhile the enemy - we

later learned it was the Australian

cruiser Sydney—had steamed

away to capture our landing

party on Direction Island. We

settled down to a night of hell,

surrounded by our wounded

shipmates for whom we could do

nothing, all of us threatened with

a fiery death from the still raging

flames. At dawn we started our

second day of torture. Many of

the wounded were delirious. It

was agreed if the Sydney didn’t

return we would all be lost.

In the afternoon, however, the

Sydney was sighted. Good. Our

wounded would have their chance.

We thought the British were

going to rescue us. But suddenly

salvo after salvo came from the

cruiser. Shells plowed into the

stricken Emden and exploded.

Fires again sprang up everywhere.

I saw a stoker sink down to the

deck, a shell splinter driven into

the back of his head. Another lad

screamed in agony.

The captain again gave permission

to jump overboard. Again

a few tried it, only to be crushed

on the reef. The captain, however,

stood there among his men.

His face showed that he was

carrying the paid and suffering of

all those about him. He looked at

the enemy, and I believe that for

an instant a look of supreme

contempt passed over his

countenance. Then he ordered that

the German ensign be hauled

down and a white flag hoisted.

The firing ceased immediately.

Later, two cutters were sent to

us and the officer in charge stated

that the Emden's crew would be

taken aboard the Sydney if Captain

von Müller would give his

word that none of his men would

commit any unfriendly act. A

boat was sent for the handful of

men who had landed. They were

brought back half mad from

thirst and hunger. There had

been neither water nor food on

the island.

On the Sydney the British

sailors were all kindness. Our

wounded were rushed to the

operating room. Highballs revived us

and we tasted the first food we

had had in over 36 hours.

That night our hosts, or captors,

laid before us a wireless

message containing editorial

comment on the destruction of our

ship. The London Telegraph said:

"It is almost in our hearts to

regret that the Emden has been

destroyed." In the 20 years that

have passed, the verdict of the

world has not changed, and the

Emden has earned a niche in the

hall of immortal ships.

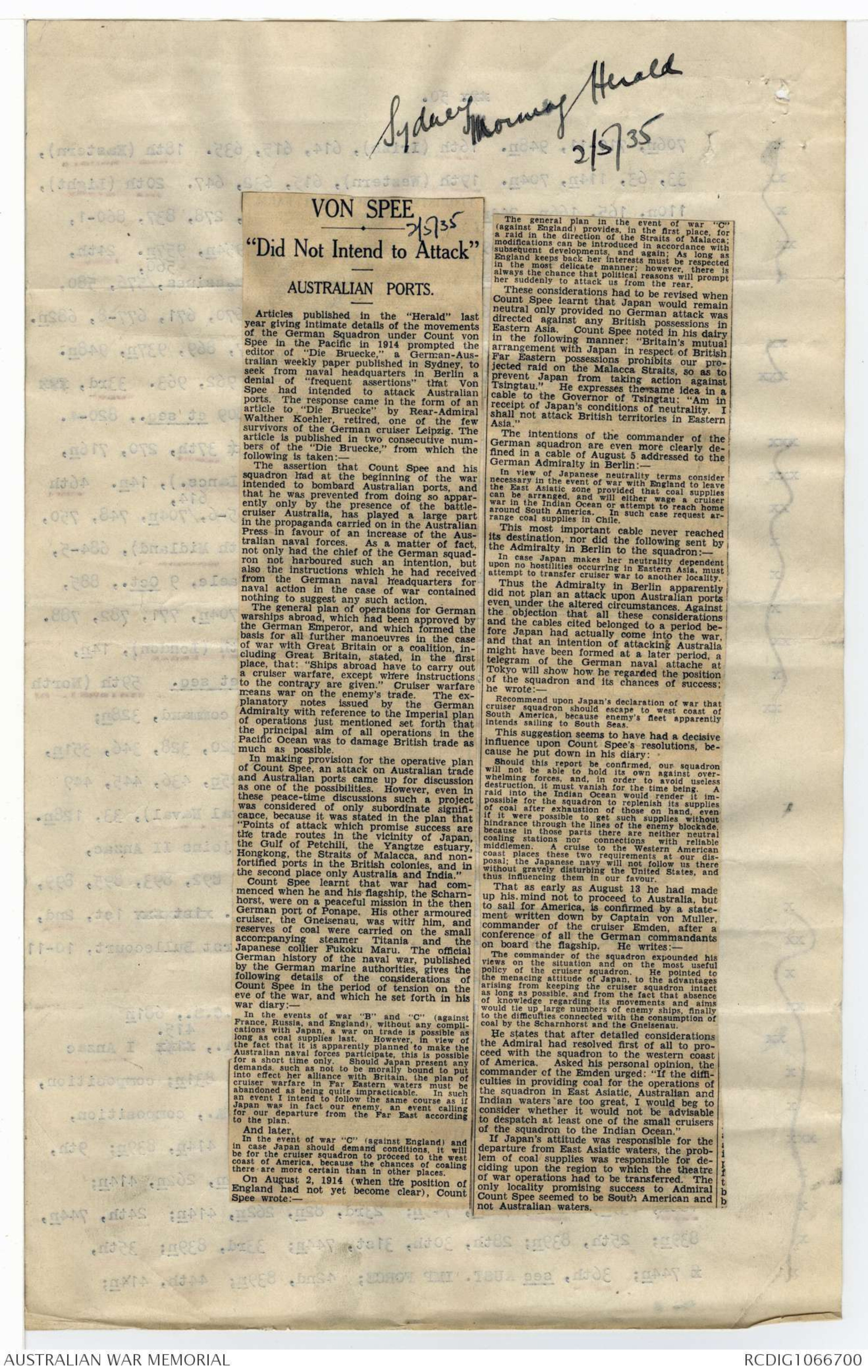

[*Sydney Morning Herald

2/5/35*]

VON SPEE

[*2/5/35*]

"Did Not Intend to Attack"

AUSTRALIAN PORTS.

Articles published in the "Herald" last

year giving intimate details of the movements

of the German Squadron under Count von

Spee in the Pacific in 1914 prompted the

editor of "Die Bruecke," a German-Australian

weekly paper published in Sydney, to

seek from naval headquarters in Berlin a

denial of "frequent assertions" that Von

Spee had intended to attack Australian

ports. The response came in the form of an

article to "Die Bruecke" by Rear-Admiral

Walther Koehler, retired, one of the few

survivors of the German cruiser Leipzig. The

article is published in two consecutive numbers

of the "Die Bruecke," from which the

following is taken:-

The assertion that Count Spee and his

squadron had at the beginning of the war

intended to bombard Australian ports, and

that he was prevented from doing so apparently

only by the presence of the battlecruiser

Australia, has played a large part

in the propaganda carried on in the Australian

Press in favour of an increase of the Australian

naval forces. As a matter of fact,

not only had the chief of the German squadron

not harboured such an intention, but

also the instructions which he had received

from the German naval headquarters for

naval action in the case of war contained

nothing to suggest any such action.

The general plan of operations for German

warships abroad, which had been approved by

the German Emperor, and which formed the

basis for all further manoeuvres in the case

of war with Great Britain or a coalition, including

Great Britain, stated, in the first

place, that: "Ships abroad have to carry out

a cruiser warfare, except where instructions

to the contrary are given." Cruiser warfare

means war on the enemy's trade. The

explanatory notes issued by the German

Admiralty with reference to the Imperial plan

of operations just mentioned set forth that

the principal aim of all operations in the

Pacific Ocean was to damage British trade as

much as possible.

In making provision for the operative plan

of Count Spee, an attack on Australian trade

and Australian ports came up for discussion

as one of the possibilities. However, even in

these peace-time discussions such a project

was considered of only subordinate significance,

because it was stated in the plan that

"Points of attack which promise success are

the trade routes in the vicinity of Japan,

the Gulf of Petchili, the Yangtze estuary,

Hongkong, the Straits of Malacca, and non-fortified

ports in the British colonies, and in

the second place only Australia and India."

Count Spee learnt that war had commenced

when he and his flagship, the Scharnhorst,

were on a peaceful mission in the then

German port of Ponape. His other armoured

cruiser, the Gneisenau, was with him, and

reserves of coal were carried on the small

accompanying steamer Titania and the

Japanese collier Fukoku Maru. The official

German history of the naval war, published

by the German marine authorities, gives the

following details of the considerations of

Count Spee in the period of tension on the

eve of the war, and which he set forth in his

war diary:-

In the events of war "B" and "C" (against

France, Russia, and England), without any

complications with Japan, a war on trade is possible as

long as coal supplies last. However, in view of

the fact that it is apparently planned to make the

Australian naval forces participate, this is possible

for a short time only. Should Japan present any

demands, such as not to be morally bound to put

into effect her alliance with Britain, the plan of

cruiser warfare in Far Eastern waters must be

abandoned as being quite impracticable. In such

an event I intend to follow the same course as if

Japan was in face our enemy, an event calling

for our departure from the Far East according

to the plan.

And later,

In the event of war "C" (against England) and

in case Japan should demand conditions, it will

be for the cruiser squadron to proceed to the west

coast of America, because the chances of coaling

there are more certain than in other places.

On August 2, 1914 (when the position of

England had not yet become clear), Count

Spee wrote:-

The general plan in the event of war "C"

(against England) provides, in the first place, for

a raid in the direction of the Straits of Malacca;

modifications can be introduced in accordance with

subsequent developments, and again: As long as

England keeps back her interests must be respected

in the most delicate manner: however, there is

always the chance that political reasons will prompt

her suddenly to attack us from the rear.

These considerations had to be revised when

Count Spee learnt that Japan would remain

neutral only provided no German attack was

directed against any British possessions in

Eastern Asia. Count Spee noted in his diary

in the following manner: "Britain's mutual

arrangement with Japan in respect of British

Far Eastern possessions prohibits our projected

raid on the Malacca Straits, so as to

prevent Japan from taking action against

Tsingtau." He expresses the same idea in a

cable to the Governor of Tsingtau: "Am in

receipt of Japan's conditions of neutrality. I

shall not attack British territories in Eastern

Asia."

The intentions of the commander of the

German squadron are even more clearly

defined in a cable of August 5 addressed to the

German Admiralty in Berlin:-

In view of Japanese neutrality terms consider

necessary in the event of war with England to leave

the East Asiatic zone provided that coal supplies

can be arranged, and will either wage a cruiser

war in the Indian Ocean or attempt to reach home

around South America. In such case request

arrange coal supplies in Chile.

This most important cable never reached

its destination, nor did the following sent by

the Admiralty in Berlin to the squadron:-

In case Japan makes her neutrality dependent

upon no hostilities occurring in Eastern Asia, must

attempt to transfer cruiser war to another locality.

Thus the Admiralty in Berlin apparently

did not plan an attack upon Australian ports

even under the altered circumstances. Against

the objection that all these considerations

and the cables cited belonged to a period

before Japan had actually come into the war,

and that an intention of attacking Australia

might have been formed at a later period, a

telegram of the German naval attache at

Tokyo will show how he regarded the position

of the squadron and its chances of success:

he wrote:-

Recommend upon Japan's declaration of war that

cruiser squadron should escape to west coast of

South America, because enemy's fleet apparently

intends sailing to South Seas.

This suggestion seems to have had a decisive

influence upon Count Spee's resolutions,

because he put down in his diary:

Should this report be confirmed, our squadron

will not be able to hold its own against

overwhelming forces, and, in order to avoid useless

destruction, it must vanish for the time being. A

raid into the Indian Ocean would render it

impossible for the squadron to replenish its supplies

of coal after exhaustion of those on hand, even

if it were possible to get such supplies without

hindrance through the lines of the enemy blockade,

because in those parts there are neither neutral

coaling stations nor connections with reliable

middlemen. A cruise to the Western American

coast places these two requirements at our

disposal; the Japanese navy will not follow us there

without gravely disturbing the United States, and

thus influencing them in our favour.

That as early as August 13 he had made

up his mind not to proceed to Australia, but

to sail for America, is confirmed by a statement

written down by Captain von Muller,

commander of the cruiser Emden, after a

conference of all the German commandants

on board the flagship. He writes:-

The commander of the squadron expounded his

views on the situation and on the most useful

policy of the cruiser squadron. He pointed to

the menacing attitude of Japan, to the advantages

arising from keeping the cruiser squadron intact

as long as possible, and from the fact that absence

of knowledge regarding its movements and aims

would tie up large numbers of enemy ships, finally

to the difficulties connected with the consumption of

coal by the Scharnhorst and the Gneisenau.

He states that after detailed considerations

the Admiral had resolved first of all to proceed

with the squadron to the western coast

of America. Asked his personal opinion, the

commander of the Emden urged: "If the

difficulties in providing coal for the operations of

the squadron in East Asiatic, Australian and

Indian waters are too great, I would beg to

consider whether it would not be advisable

to despatch at least one of the small cruisers

of the squadron to the Indian Ocean."

If Japan's attitude was responsible for the

departure from East Asiatic waters, the problem

of coal supplies was responsible for deciding

upon the region to which the theatre

of war operations had to be transferred. The

only locality promising success to Admiral

Count Spee seemed to be South American and

not Australian waters.

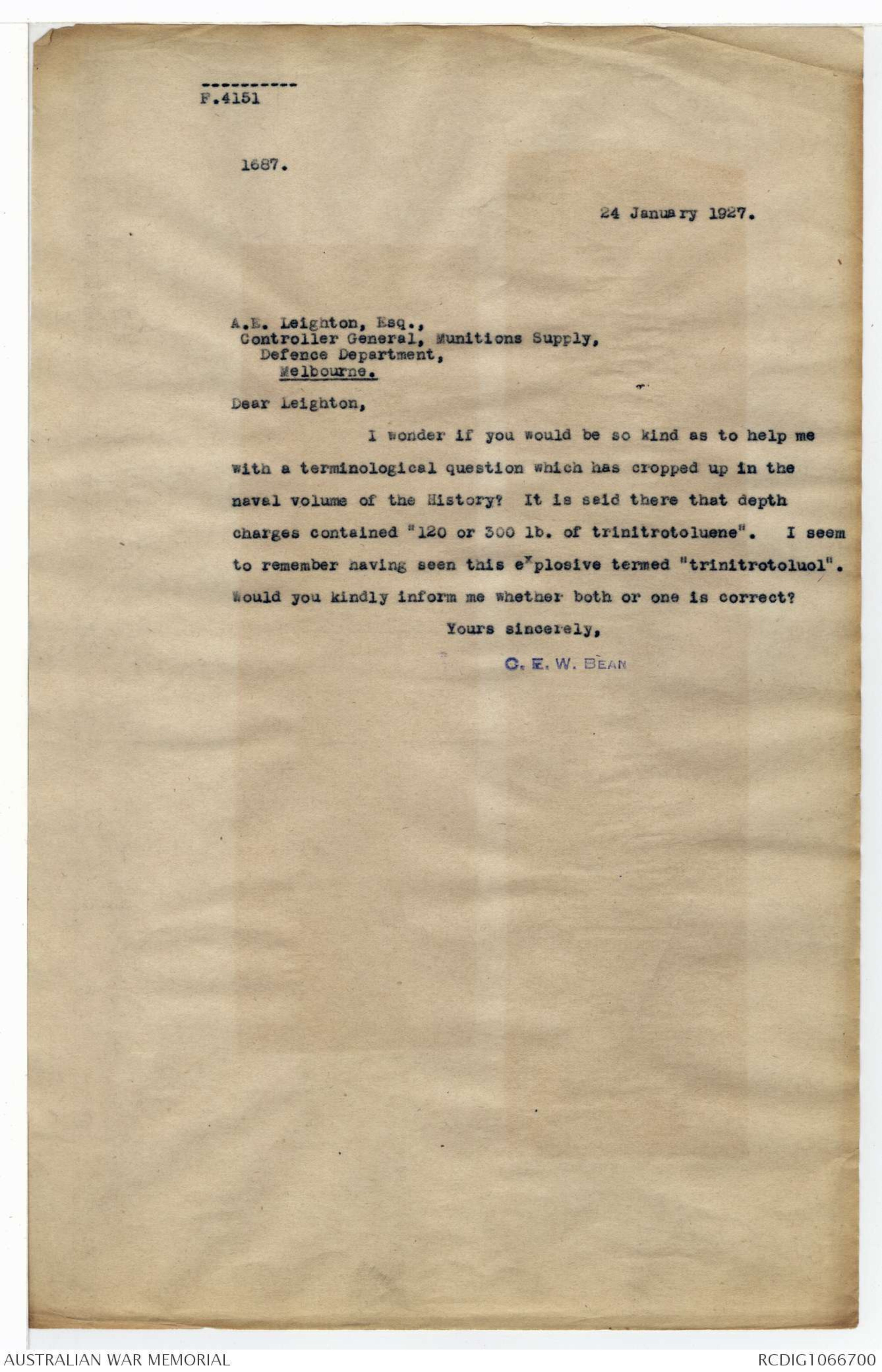

F.4151

1687.

24 January 1927.

A. E. Leighton, Esq.,

Controller General, Munitions Supply,

Defence Department,

Melbourne.

Dear Leighton,

I wonder if you would be so kind as to help me

with a terminological question which has cropped up in the

naval volume of the History? It is said there that depth

charges contained "120 or 300 1b. of trinitrotoluene". I seem

to remember having seen this explosive termed "trinitrotoluol".

Would you kindly inform me whether both or one is correct?

Yours sincerely,

C. E. W. BEAN

Not Yet Replaced By AI

Not Yet Replaced By AIThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.