Charles E W Bean, Diaries, AWM38 3DRL 606/262/1 - 1916 - 1934 - Part 2

[*Times Literary Supplement 26/12/29*]

ENGLAND AND THE

ENCIRCLING POLICY

DER GEIST DER ENGLISCHEN POLITIK UND DER

GESPENST DER EINKREISUNG DEUTSCHLANDS.

By HERMANN KANTOROWICZ.

(Berlin: Ernst Rowholt. 16m.50.)

This is a brave book for a German to have

written, but a sombre one for Englishmen to

read. Yet it thoroughly fulfils its purpose,

which is to do justice to England and especially

to clear English policy of the charge of

“encircling” Germany as the cause of the

War. It does this completely. Then why

should it be so sombre? An explanation is

necessary, and it will be found in the last

two chapters. One of these describes the

propaganda still carried on to-day to keep

alive what Professor Kantorowicz calls the

“spectre ” of encirclement; the other is entitled

“Shadows over England.” The former

will be read with general astonishment by

Englishmen; the latter with different feelings

according to the tendency of the reader

towards optimism or pessimism; but it will

be allowed by all to contain only too much

truth. Let no one suppose that this book

can be lightly overlooked, like a War pamphlet

or any other fugitive product of passion;

it is a very solid book by an extremely serious

writer, who has a thorough knowledge of

English history and a remarkable insight into

English character. The description of it on

the jacket is “a thorough and brilliant encyclopaedia

of Britishism." This may be a little

overstated, but it is near enough to the truth

to pass muster. The author himself shared

the views of his countrymen about England,

which were universally expressed in the

exclamation “Gott strafe England !” during the

War; but since then he has studied the subject

afresh and come to the conclusion that

the encircling policy never existed and that

the idea of it is incompatible with the British

character. We know that very well, and

consequently never took the accusation seriously.

Nor would it matter now if it had come to an

end with the War, which is the natural

conclusion to be drawn from all the subsequent

events. But it is not the conclusion drawn

in Germany; and this is the important thing

that he has to tell us.

The rest of his book may be passed over

briefly, not because it is less important but

because it is addressed rather to German than

to English readers, who will not care to linger

over the many pleasant things said about

England or to hear their own virtues extolled,

and sometimes perhaps over-extolled. This

part of the book runs to some three hundred

pages and is divided into four chapters, which

analyse the English character under the

headings : (1) Chivalry, (2) Objectivity

(Sachlichkeit), (3) Humanity, and (4) Irrationality.

These chapters are thoroughly

worked out and illustrated with many

historical examples. In the first of them the

author shows a subtle appreciation of the

significance of the English terms—chivalry,

gentleman, tact, sport, fair play,

thick-skinned—and others which have never been

subjected to such close examination. He

thinks the English are too careless of dignity

(Würde) in certain matters. He takes the

English view of King George and Admiral

Jellicoe enjoying themselves at Wembley,

which caused astonishment on the Continent,

but regards the meek reception or the ignoring

of insulting remarks as a weakness. He

mentions several instances of German rudeness

to British statesmen who took no notice

of it, and says that pacifists will be inclined

to approve highly of such conduct; but he

doubts if a more dignified demeanour would

not have served the cause of peace better.

An extreme case is the post-War propaganda

of Germany’s complete innocence and the

corresponding guiltiness of the Allies—

particularly England—who alone caused the War

and then in the Treaty of Versailles put all

the blame on innocent Germany. He finds

the unqualified friendliness of England in the

face of this accusation a moral lack of backbone

and calls it the “English sickness."

This is directly connected with the question

of the movement for keeping alive the story

of the encirclement of Germany by the

Allies. We are told that the movement is a

powerful and successful undertaking,

inspired by a passionate patriotism. It is

thoroughly organized and has thousands of

threads, which run together and meet in

three central bodies in Berlin. This gigantic

organization controls its own Parliamentary,

diplomatic, official, scientific, educational,

journalistic bookshop, commercial, military,

and clerical sub-organizations; and makes use

of every imaginable means to spread the tale

of German innocence. The literary output

of one of the three central bodies—the

Arbeitsausshuss deutscher Verbände—runs

into millions. Their foreign department is

particularly active. A single one of the

constituent societies—the Wirtschaftspolitische

Gesellschaft—has five hundred foreign representatives,

who regularly receive their publications

and supply English and American

politicians with material, while the central

body has a standing connexion with 170

German newspapers in foreign countries. For

home use a common practice is for their

representatives to take articles communicated

to the central sheet and publish them in the

local Press as original matter, which is held

to be a particularly useful method of

enlightenment. This organization has 1,100

branches and is actively supported by

all sections of the people and by the

Government. With regard to the special

part played by England, Professor Kantorowicz

quotes from the official “Catechism of

War Guilt," published by the society:—

The English policy under the leadership of

Edward VII. undertook the task of winning over

the two natural enemies of Great Britain, France

and Russia, in order to destroy the new German

rival. Destruction of German trade and the

German fleet—these were the primary aims of

English policy, not only under Edward VII., but

also under his successor and the responsible

statesmen.

This is not the “spectre” of the story of

encirclement, but the story itself ; and

Professor Kantorowicz shows that the writer, in

order to prove that Sir Edward Grey was only

trying to gain time, has altered his report of

July 25, 1914. Further details of the propaganda

in military, clerical, journalistic, historical

and diplomatic circles are given, and

above all in the school books. He says that a

monomaniac intoxication has seized on almost

the whole German people. Its ultimate object

is the denunciation of the Versailles Treaty.

He does not write for us, but for his fellow-countrymen,

whose honour is concerned in this

organized propagation of a known and admitted

falsehood. But his concluding words,

coming from a sincere friend to England, do

touch us.

“Shadows over England” is very short—

too short to be called a chapter—but it

deserves serious consideration. It begins by

admitting that England's downfall has often

been predicted in the past, and the British

Lion, whom it is difficult to arouse but impossible

to subdue, has arisen greater than ever

from ever greater difficulties. But to-day,

when many Englishmen for the first time

despair of the future, it seems to have come

to a turning-point in its history and to be

about to sink slowly, while other Powers,

and particularly Germany, will rise. It

is possible, and in his opinion probable,

that the flames of an ever-rising nationalism

will unite in a new conflagration, in which the

last bulwark of European thought—England's

power—will find its end together with civilization

in general. In that case Grillparzer's

saying will be justified—that the way of the

new culture is from Humanism through

Nationalism to Bestialism. But in any case

England is threatened with dangers on every

hand. Economically it shrinks daily, being

beaten in wealth by America, in organizing

power and technical capacity by Germany,

with which it cannot compare, in population

and extensibility by Russia. Its industrial

plant is obsolete, its employers are not minded

to work as their competitors do, its labour

clings to wages which the employers can no

longer afford. Unemployment looks like a

permanent phenomenon, yet emigration fails,

because the pioneering spirit at home and the

youthful optimism in the Dominions are

extinguished. Religion is dying out and is not

replaced by nationalism, as in other countries ;

but, on the contrary, gives way to an extreme

pacifism and internationalism. Its population

figures show an alarming decrease of vitality,

and the distribution of the people between

town and country grows ever more unsound.

Its insular security is undermined by submarines,

mines and aeroplanes. There is no

war in sight; but if war came England has no

friend. France is disillusioned, Italy envious,

Russia full of hate, Japan inscrutable and

the American luxury fleet will not for ever

content itself with parity. Germany, too, will

one day demand back her fleet and colonies.

In the rising world of Islam from Angora to

Mecca and from Cairo to Delhi England has

far more enemies than friends, and the China

of the future sees in England the worst of the

White Devils. The colonial epoch seems to

have finally run its course for all nations, but

the greatest dangers await the State which has

the largest colonial possessions. India will

not be held permanently in the day of

nationalism, the rule over Egypt is diminishing,

the mandate over Iraq is already denounced

and Palestine is nothing but a

burden. He admits that the British Dominions

are, since the “constitution" of 1926, tied

more closely to the Motherland because less

chained; but he doubts if a mere family connexion

will hold indefinitely.

If these dangers are realized, then the stream

of English history will not broaden to a

second Imperium Romanum but will dwindle

to a second Holland. However, they may

not be. One can never forecast the future in

details, but only the general tendency can be

perceived, and how long that will last is

known only to the gods. So hope remains for

mankind : and for England herself the task of

making her future worthy of her past.

[*Times Literary Supplement 30/1/30*]

THE ORIGINS OF THE WAR

DOCUMENTS DIPLOMATIQUES FRANCAIS (1871-

1914). 1re Série (1871-1900). Tome

Premier. (Paris: Alfred Costes and

L’Europe Nouvelle.)

In his brief Introduction to this, the French

collection of Diplomatic Documents from

1871 onwards, M. Charléty, the President

of the Commission charged with the

publication, states the principles on which the

work has been conducted. It is, he says,

the work of historians, who have been

influenced by no other considerations than

historic truth ; the documents are printed

without comment of any sort ; and all those of

importance are given without reserve, gaps in

the archives being supplied from other

sources, occasionally even by reference to the

German collections. In the case of the present

volume, indeed, which deals with a period

comparatively remote, the selection of documents

has been restricted to those which

throw light on “the great lines and general

orientation of French policy,” and the record

is less full than will be the case in later

volumes. It may be said at once, however,

that the selection has been made with admirable

judgment and impartiality, and that

nothing of importance has been omitted.

The present volume opens with the text

of the Treaty of Frankfurt, which ended the

Franco-German War; it closes with the termination

of the crisis which, from 1873 onward,

and notably in 1875, had threatened

an immediate renewal of the war. The relations

between France and Germany being

the most important question during this

period, the great majority of the documents

are concerned with these. Thus the book

naturally falls into two parts, the first covering

the period of the German occupation, to

March, 1873, the second that of French

reconstruction and the consequent alarms.

The impression gained from these documents,

and from those published in the German

collections, is that the decision to trace the

origins of the World War back to 1871 has

been fully justified. There is evidence enough

to show that French Ministers did not desire

war, for their secret dispatches are as emphatic

in this sense as their public speeches.

But there is also evidence that German fears

for the future were not wholly groundless.

Thus, apropos of the meeting of the German

and Austrian Emperors at Gastein, Thiers

writes to General Le Flô, the French Ambassador

in St. Petersburg, that if the friendly

exchanges of the two German Powers are

serious, “Russia, which has not forgiven

Austria for her famous ingratitude and her

courting of the Poles, will gravitate towards

us.” He counsels prudence, however, so as not

to hazard a rebuff by precipitate advances :

“Our present attitude ought to be one of

calmness and confidence," in the certain

conviction that “with two or three years of

good government, France will be as strong

and as respected as ever." That was in

September, 1873. On May 29, 1875, Le Flô writes

to the Duc Decazes that in an interview with

the Emperor Alexander he has “touched

delicately" on the subject of Alsace-Lorraine.

If we compare this with the utterances of

Bismarck, reported in the German collection,

we have the key to the situation. Thus, on

October 30, 1873, he writes to Count Arnim,

the German Ambassador in Paris :-

You yourself described the situation accurately as

a truce, which France reserves to herself the right

to denounce at the first favourable moment; and

a pacific speech or an open dispatch of the Duc

de Broglie alters nothing in this.

Or again :-

No Government would be so foolish, when it

regards war as inevitable, as to leave to its opponent

the free choice of time and opportunity and

to await the moment most convenient to the

enemy.

And in a letter addressed to the Ambassador

in St. Petersburg, on February 28, 1874, he

writes :-

It is not surprising that the other Powers should

look on the development of things in France with

other eyes; they are not the neighbours of the

French, while Germany forms as it were the buffer

of Europe against the invasions of a warlike

people . . . our policy is defensive.

In his Reminiscences Bismarck says that

he was far from desiring war; and this

seems to be true. But it is equally certain

that he regarded renewed war with France

as sooner or later inevitable; and, since it was

so regarded, Moltke and the General Staff

were urgent that Germany should strike at

once, on the old Frederician principle of the

“offensive-defensive," before France had had

time to reorganize her Army. The Vicomte

de Gontaut-Biron, French Ambassador in

Berlin, reports a conversation with Herr von

Radowitz, Bismarck's right-hand man, who

frankly declared this to be the right thing

to do—on Christian principles! Upon which

the Duc Decazes commented that the right

to destroy those who might became a danger

was altogether new to international law, and

was a theory that threatened every Power in

Europe. And so the diplomatic debate went

on, to the accompaniment of war-trumpets

blown—crescendo or diminuendo, according

to the shifting moods of the Chancellor's

“tortuous and provocative policy”—by the

semi-official Press of Berlin, to which the

irresponsible papers in France replied by

defiant crows.

Amid this babel the efforts of French

diplomacy were mainly directed to soothing

the Chancellor's “irritable nerves.” He had,

indeed, reason to be irritable. He had

declared war on Ultramontanism, and in

doing so—as the Emperor Francis Joseph said

—had “taken the wrong turning.” He had

visions of a resuscitated France in league with

the Pope and the Catholic Powers to crush

Germany. The refusal of the French crown

by the Comte de Chambord came as a relief;

but Marshal Macmahon, President since the

fall of Thiers in May, 1873, was a dark horse,

[*2*]

devoutly Catholic, naturally militarist; and

France under his strong hand would be more

dangerous than when governed by Gambetta's

Radical rabble. Then, in August, the Bishop

of Nancy, part of whose diocese now lay in

German territory, issued a Pastoral in which

he invited his flock to pray for the restoration

of Alsace and Lorraine to France. Other

Bishops followed his example, with the result

that the Revanche became mixed up in

Bismarck's mind with the Kulturkampf, and so

produced the first serious crisis in Franco-German

relations. He demanded that the

French Government should take disciplinary

measures against the Bishops under a law of

1819; to which the obvious objection was that

this law provided for trial by jury and that

no jury would convict. The Government did

what it could; an admonitory circular was

addressed to the Bishops by the Minister of

Public Worship, and the question was ultimately

settled by a successful appeal to the

Pope to rearrange the dioceses so that they

should not overlap national frontiers. Meanwhile,

however, the affair had started a

violent campaign against France in the German

Press, which was renewed after the condemnation

of Bazaine in December. From

Berlin M. de Gontaut reported that the object

of this seemed to be to secure an anti-Catholic

majority in the Reichstag and to

ensure the passage of the military Budget.

But the French were alarmed, in spite of the

Emperor Alexander's assurance that all this

was but a ruse of Bismarck's and that

nobody wanted war. In a circular of March

27, 1874, the Duc Decazes announced that

the affair of the Bishops was settled, but that

this did not exclude the probability of “fresh

pretensions, perhaps no less exorbitant, being

pushed beaucoup plus au fond.” Point was

given to this when, on April 14, the Reichstag

by a very large majority passed the Bill raising

the effective force of the German Army to

401,000 men, after a speech in which Moltke

enlarged on the enmity of the French and

their continual preoccupation with the idea of

revenge.

The immediate object of the German

Government having been thus secured, outward

calm prevailed; but the documents show

that beneath the surface the nervousness and

the agitation continued. It was not, however,

till the early spring of 1875 that the

crisis once more became acute. A plot to

assassinate Bismarck, hatched in Belgium,

led to a peremptory demand for special legislation,

addressed from Berlin to the Government

in Brussels. Apart from the general resentment

aroused by this pretension to dictate laws to

an independent State, ulterior designs were

suspected. On March 5 Baron Baude, the

French Minister in Brussels, addressed to the

Duc Decazes a dispatch which had a prophetic

ring. In the next war, he said, the

Germans would aim at seizing Belgium and

Holland, thus securing the estuaries of the

Rhine, the Meuse and the Scheldt, together

with the Pas de Calais, which would enable

them to build up their sea-power and

establish a colonial empire. And war seemed

imminent. On March 4 the export of horses from

Germany was forbidden, and from time to

time information reached Paris of vast purchases

of munitions by the German Government.

From Austria the French Ambassador

wrote, on April 2, that all the reports converging

on Vienna were to the effect that

Prussia would be ready for war in June. The

climax came with the publication in the

Berlin Post on April 10 of an article, under

the heading “Is War in Sight?” which

was assumed to be inspired, and created

an immense sensation. Bismarck himself

asserted that it had taken him by

surprise, and next day there appeared in the

semi-official Norddeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung

a démenti, which, however, only made

things worse, since it declared that “the

expenditure which the measures for military

reorganization impose upon France is too

heavy to be borne for long even by the richest

nation; it is plain that they have for their

object preparations of which the aim cannot

but be obvious to every clear-seeing eye."

Even to the Emperor William this pronouncement

seemed "anything but calming.” To

the rest of the world it looked like a deliberate

threat.

Yet the Emperor Alexander was probably

right when he assured Le Flô that Germany

did not want war. Her attitude was fairly

accurately described by Count Karolyi, who

said that what she meant was : “If you attack

you will find us ready, and if we are certain

that you are going to attack we will not

await your convenience.” When Bismarck

was heckled upon the bellicose language of

the General Staff, he said “They are

soldiers, not politicians.” In view of

the general European situation, indeed,

war would have been a perilous adventure

for Germany ; for, in spite of the

League of the three Emperors, the sympathies

of all the Powers were with France. “If

Germany attacks France unprovoked,” said

the Tsar to General Le Flô, “ she will do so

at her peril, and be in the same position as

Napoleon in 1810.” And two days later he

told the Ambassador that he was going to

Berlin, where he would be “un élément calmant."

This proved to be the case. The well-known

letter of Queen Victoria to the Emperor

William and the efforts of the British Government

"to put out a fire that was not alight"

—as Bismarck scornfully remarked—had had

their effect; but it was only with the visit of

the Emperor Alexander to Berlin in May that

the crisis was ended. In the words of the

French Ambassador, “it was he who imposed

peace." In a circular letter of May 18,

addressed to the French Ambassadors, the

Duc Decazes said that “the general opinion

has not supported this extension of the rights

of the victor, it has not supported the idea

of an attack on France, under pretext of the

beginning of a military reorganization, by a

powerfully armed neighbour," and he spoke

of the intervention of Great Britain and

Russia as “the first sign of the formation

of some sort of concert for ensuring the

general peace."

[*The Times Literary Supplement 2/10/30*]

THE MOROCCO CRISIS

THE FIRST MOROCCAN CRISIS, 1904-1906. By

EUGENE N. ANDERSON. (University of

Chicago Press. London: Cambridge

University Press. 21s. net.)

The publication of the British, French and

German diplomatic documents has stimulated

historians in many countries into composing

closely documented monographs on

different questions of foreign policy before the

War. Though America was only indirectly

concerned in these questions, American historians

have been just as active in this field as

those of any European country, and it is

probable that many more volumes such

as the present book on Morocco may be

expected from them in the future. Work of

this kind is little more than spade-work ; the

piecing together of the facts contained in

official dispatches, memoirs, biographies and

newspapers is the main preoccupation. Little

attempt is made at generalization, or at studying

the internal development of social forces in

the European countries in order to interpret

the diplomatic moves of the Governments.

Diplomacy is merely the executive instrument

for carrying through a policy dictated by

considerations which are vital to the national

existence; and no nation, therefore, can be

adequately judged by the success or failure

of its diplomacy. The real importance lies in

the considerations which prompted such and

such diplomatic action. The inadequacy of

histories such as the present is that the reader

soon becomes lost in a maze of diplomatic

intrigue and finds it extremely difficult to see

the wood for the trees. Diplomatic histories

must be primarily regarded as written by

students for students ; the larger public is

unlikely to gain a clearer comprehension of the

real issues at stake from their perusal.

Mr. Anderson’s book certainly is carefully

and conscientiously written. He has

pieced together all the material available and

his book, though it demands close reading,

gives a clear picture of the progress of events.

What it lacks is any human interest,

any dramatic representation of the clash of

personalities and national character. Mr.

Harold Nicolson's “Life of Lord Carnock,"

which appeared in April this year, was

evidently not available to Mr. Anderson

while engaged on his present work.

Lord Carnock spent many years in

Morocco as British diplomatic representative

there, and was finally appointed to

lead the British delegation at the Conference

of Algeciras in 1906. Mr. Nicolson, in writing

the life of his father, traced the whole course

of the Moroccan crisis from its beginnings to

the same date at which Mr. Anderson's book

closes with the decisions of the Conference of

Algeciras. But Mr. Nicolson, though writing

the life of a diplomatist and dealing with

diplomatic documents, succeeded in linking

the Moroccan crisis on to wider questions of

European development and in giving the

events themselves a dramatic significance

which deepens their historic meaning and

makes them stand out in the memory with a

more personal reality. For those who may

have read Mr. Nicolson’s striking tribute to

his father’s work in Morocco with some hesitation,

lest it might have been influenced by

filial affection, it may be of interest to learn

that an impartial American, such as Mr.

Anderson shows himself to be, fully endorses

it. Speaking of the Conference of Algeciras,

he writes :-

Sir Arthur Nicolson was the most astute member

taking an active part in the assembly, although he

played his role so quietly that the other delegates,

particularly the Germans, did not perceive his significance.

A true diplomat, he carried out the difficult

British policy admirably. It was primarily

his work that the Conference thrashed the fundamental

problems through to a definite conclusion.

The importance of Morocco before the War

lay in the fact that its problems provided the

material by which the strength of the rival

European combinations could be tested.

Not only was the newly formed Anglo-French

Entente given its baptism of diplomatic fire,

but the real weakness of the Triple Alliance

was exposed. At the end of the crisis France,

in taking stock of her position, could pride

herself on having risen from the position of

an inferior to that of a political equal to

Germany. The actual problems of Morocco,

in so far as they affected the welfare of the

inhabitants themselves, were almost lost sight

of in face of the all-absorbing question of the

European balance of power; and at the end

of the crisis Morocco and its troubles were

soon forgotten, for the European danger had

been brought out into the open and now

loomed before the countries mainly concerned

in all its grim reality. Mr. Anderson sums up

the results of the long-drawn-out crisis in the

following sentences :-

Neither side appreciated the other's point of

view ; neither heeded the other's warnings.

Each side accused the other of aiming at

its defeat, of being a menace. Each scoffed

at the other's fears, but each continued to

arm and to broaden and tighten the policy which

each warned the other was leading to trouble.

Neither side had learned anything from this episode

except to be more cautious. Neither changed its

męthod. . . . The Moroccan problem both in

its local and in its international aspects left behind

plenty of raw material from which future conflicts

could arise. The crisis was only the first of these

episodes born of the clashings of mutual fears and

ambitions, nurtured on hazardous playing with

war and on diplomatic blunderings. The road to

Armageddon lay open.

KAISER AND CHANCELLOR

KAISER AND CHANCELLOR. THE OPENING

YEARS OF THE REIGN OF WILLIAM II.

By KARL FRIEDRICH NOWAK. Translated

by E. W. DICKES. (Putnam. 21s.

net.)

This important book is to some extent

a continuation of William II.’s own memoirs

of his childhood and youth, since it is based

upon materials, written and verbal, which

he himself supplied. Dr. Nowak, however,

has not been content to make a book out

of the evidence set before him. He has

carefully tested its accuracy both by

reference to the collections of German and

Austrian official documents published since

the War and by personal visits to statesmen,

ambassadors, and other eminent figures in

contact with the Emperor at the beginning

of his reign. Besides this he claimed and

has freely exercised the historian's right to

complete liberty of judgment in the presentation

of his material. The case which he

submits is thus the Emperor’s case, critically

treated ; and the analysis of William II.'s

mind and temperament at the time of his

accession makes it clear that his Chancellor

had very great difficulties to contend with.

Particular stress is laid on the theatricalism

of the young Emperor’s character, a quality

exceptionally trying to such a hardened

Real-politiker as Bismarck :-

He had caught the infection of the magnificent

bombast of Bayreuth. Like so many others, he

too was affected and influenced by Wagner's

resplendent leit-motifs, his sense of the decorative

in exalted passions, more than life-size characters,

supernatural powers, the atmosphere of incense

hanging over every scene, Lohengrin’s glistening

armour and the glory of Siegfried's sword ; all

these heightened the colours of life for him, gratified

the sense of romance and the desire for the scenic

and picturesque, so that he seemed himself to be

on the stage among the bright footlights.

If this Wagnerian influence had manifested

itself only in a taste for the melodramatic

all might have gone well, for the Chancellor

was fully alive to the political value of

properly contrived effects. Unfortunately it

blended with the mysticism which was a

part of his Hohenzollern inheritance to

create in the Emperor's mind a peculiar

conception of his office :—

He made a sharp distinction between the person

and the mission. He subordinated himself to the

Kaiser in him, who had received his powers and

duties and responsibilities by the grace of God.

He saw the Monarch that he was as a power isolated

from his everyday existence, a second, disembodied

ego, eminent, remote, exalted by the will of God...

He was a living, breathing human being like the

rest ; working in many moods and in many different

fields. But his discussions and examinations of

public business, his decisions and commands, he

must carry through simply as Kaiser.

Holding such ideas, he was not in the least

likely to allow another hand to wield his

sceptre; and it is not an accident that the

final clash was brought about by Bismarck's

revival of an old Prussian Cabinet Order

which deprived departmental ministers of

free communication with their Sovereign.

On the other hand Bismarck, with his

profound knowledge of human character,

was well aware that the Emperor must be

allowed to find his feet and to appreciate

from his own experience the unquestionable

soundness of his Chancellor's advice. If

this expectation was not realized, it was not

so much because of actual faults on either

side as because the two men belonged to

different ages. As Dr. Nowak well points

out, Bismarck had worked, so long as the

old Emperor lived, with his contemporaries,

men who had been his colleagues in

the great constructive enterprise which was

completed in 1870. It may be that he might

still have cooperated with their heirs ; but the

Emperor Frederick's premature death shut

out a whole generation from its place in

German public life and brought the ageing

Chancellor into association, all the more

difficult because so sudden, not with the

sons but with the grandsons of his peers.

Here Dr. Nowak goes to the root of the

matter, and it is a pity that his sympathies

have caused him to over-colour his picture.

The breach between the Emperor and his

grandfather's most trusted friend arose out

of the nature of things. It was unnecessary

to heighten the lights and darken the shadows

by representing William II. as the figure of

youth, with all youth’s generous ideals,

surrounded by harsh and selfish intriguers.

The animus shown in revealing the weak

points of those whom the Emperor mistrusted

—the treatment of Waldersee is particularly

noticeable—is a real blemish on the book.

The conflict between age and youth, the

more inevitable because incarnate in personalities

equally self-confident and self-assertive

and both intoxicated with power—the one

with its newness and the other with its

familiarity—came to a head over the great

miners' strike in Westphalia and the numerous

smaller strikes which broke out in sympathy

with it. Here was a development which

demanded the attention of a Sovereign who felt

himself to be the guardian and adviser of all

his subjects. He sent for both parties to the

dispute and rebuked them—the men for their

disregard of the law, the owners for neglect

of their obligations to their workpeople.

The whole episode was a curious blend of

vanity and idealism, and Bismarck disapproved

of both its characteristics. But the

Emperor was in no mood to withdraw. He

busied himself with the outlines of a constructive

policy which would justify his

censures, and accordingly proposed that a

Bill should be drafted for the improvement

of conditions of labour in Germany, and that

an international conference should meet in

Berlin to formulate an agreed code of labour

legislation. Bismarck had quite other views.

His purpose was to crush Social Democracy

once and for all, and to make the strikes a

pretext for the use of force. In vain the

Emperor protested, to his great credit, against

plans which would stain the opening of his

reign with blood. It would come to firing

in the end, the Chancellor told him. The

crisis developed slowly. The Emperor does

not seem to have known of the steps

which Bismarck was taking to prevent the

assembly of the conference, but he was

very much alive to the fact that three requests

for the draft Bill had been ignored. To

vindicate his authority he called a Crown

Council. There he forced his projects

through. The two proclamations were duly

published. But the Chancellor withheld his

counter-signature ; and the Emperor had

noted with anxiety that, at the Council, no

Minister had dared to open his mouth in

defence of policies which Bismarck was

opposing. If it was not to come to firing in

the end, and he was determined that it

should not, he must see to it that the heads

of departments felt themselves to be his

servants and not the Chancellor's.

Meanwhile other difficulties were accumulating.

Dr. Nowak enumerates a series

of episodes—the unsuccessful prosecution of

Professor Geffcken for his publication of the

Emperor Frederick’s war diaries, the unsuccessful

attempt to get Sir Robert Morier

recalled from his St. Petersburg Embassy

on the ground that in 1870 he had betrayed

German military plans to the French, the

unsuccessful though furious demands on the

Swiss Government for the release of a German

police spy imprisoned for activities on Swiss

soil—for all of which Bismarck bore the

responsibility and the Emperor the discredit.

It was becoming plain that he could not

work in harmony with his “ young master."

He himself talked of resignation, and even

prepared a scheme for his gradual retirement

from affairs. But when his gusts of irritation

had passed, the love of power gripped him,

and the proffered resignation was withdrawn.

In the end the crisis came, rather oddly, over

a matter on which both were substantially

agreed—the need of strong measures to arrest

Social Democratic agitation.

Bismarck's Anti-Socialist Bill contained

a clause authorizing the deportation of urban

agitators into rural districts. The Conservatives

rebelled against this pollution

of their countryside. If Bismarck persisted,

his majority would break up and, at the

following election, the Conservatives, the

most monarchical party in the Empire,

would be in opposition to the Emperor's

Government. Bismarck rejected the

Emperor’s appeal for compromise and, as

soon as his Bill was thrown out, received

the leader of the Centre Party with a view

to negotiating a new coalition. The Emperor,

who, it would appear, suspected Bismarck

of planning a coup d'Etat, sought out the

Chancellor and complained that he had not

been informed of this new move beforehand.

It was more than the old Minister

could stand. In a tempest of rage he shouted

that he would endure this constant interference

no longer, and flung his resignation

in his master's face. The Emperor, ignoring

the outburst, again asked for the cancellation

of the Cabinet order which cut him off

from proper acquaintance with affairs. The

Chancellor said he would send it along;

it made no difference to him now. But two

days later the cancellation had not arrived,

and Bismarck now declined to send it. “At

that," wrote the Emperor in the long letter

of explanation which he addressed to the

Emperor Francis Joseph a fortnight later

(a copy going to Queen Victoria) :—

I lost patience, the old Hohenzollern family

pride mounted up. The only thing to do was to

make the old pighead knuckle under or else to

complete the separation, for now the question

was simply whether Emperor or Chancellor was

to be top dog. I had a request sent once more to

him to cancel the order, and to accommodate

himself to my desires, a request already intimated.

This he flatly refused to do. That ended the

drama. The rest you know.

As a matter of fact, the rest included something

which Francis Joseph did not yet

know. As the Emperor wished to keep

Count Herbert Bismarck as Foreign Secretary,

he might yet have agreed that the Chancellor

should relinquish his various offices gradually.

But Count Herbert refused to serve under

another chief; and, at the same time, the

Emperor learned that the Tsar had just

proposed to prolong the Reinsurance Treaty

now on the point of expiry. This was

William II.’s first news of an agreement

which he considered, in Dr. Nowak’s view

rightly, as not strictly compatible with his

obligations to his Austrian ally. The double

outrage on the dignity of his office and on his

sense of fair dealing was the last straw. The

resignation was accepted, and the last page

of the opening chapter of the reign was

finally turned.

[*The Times Literary Supplement 23/10/30*]

[*The Times Literary Supplement 30/1/30*]

EUROPE SINCE 1914. By F. LEE BENNS. 8¾X

5¾, xii.+671 pp. New York: F. S. Crofts and

Co. $5.

Mr. Benns has written a comprehensive and workmanlike

text-book, which, while intended primarily

for American students, will also be of value to

English readers. The narrative is worthy of the

well-chosen bibliography printed as an appendix,

and, apart from an error in the place of one of the

post-War conferences and the omission of Lord

Robert Cecil's name in the chapter on the formation

of the League of Nations, the detail is accurate and

complete. The method adopted is that of a

chronicle, events being noted in their order, mostly

without comment. The narrative is distinguished

by a remarkable detachment, and this quality

is of special value in the chapters on Fascist

Italy and Soviet Russia. It carries with it,

however, the assumption that Europe is an entity

apart, with whose affairs America had nothing to

do except while she was actually a belligerent. The

reaction of the Senate's rejection of the Treaty of

Versailles upon European politics is nowhere hinted

at. Indeed, so far does Mr. Benns go that, in observing

that the Young Plan “ destroyed the fiction

that the problems of war debts and reparation were

unconnected," he does not say where that fiction

originated. Mr. Benns's judgments on events are

infrequent, moderate, and with one exception above

challenge. He should, however, reconsider his emphatic

statement that the collapse of the Hohenzollern

Empire was "most unexpected.” On the

contrary, it was a commonplace of European, and

especially of German, thought in the years before

the War that an Empire created by victory could

not survive defeat. This conviction is reflected

in Germany's 1914 slogan, “Weltmacht oder

Niedergang." Failure to appreciate this point leads

Mr. Benns a little astray in his reference to the effect

on German opinion of President Wilson's refusal to

negotiate with the Monarchy. The “revulsion of

popular feeling” to which Mr. Benns refers had set

in some time before the President's declaration, and

his language only opened the way for its frank

expression.

June, 1931 HEADWAY III

HEADWAY

June 1931

Tirpitz's Example

Two books have just been translated from the

German and published in this country. One,

the memoirs of the former German Chancellor

and Minister of Foreign Affairs, Prince Bülow, lifts

the veil with an astonishing and unblushing candour

on all that was most treacherous and deceitful

in German policy before the war, as shaped by the

very writer of the memoirs himself. The main

purpose of Bülow was to establish the legend of

a deliberate British encirclement of Germany. The

main purpose of the other writer, Dr. Hermann

Kantorowicz, Professor of Law in the University

of Kiel, is to brand that legend as a baseless myth

and to demonstrate how Great Britain strove,

equally under Lansdowne and Grey, for cordial

relations with Germany and the avoidance of any

situation that might lead to war.

The appearance of a work so able and so resolute

in its pursuit of truth is a notable service to "the

good understanding between nations on which

peace depends.” But the book is mentioned here

for other reasons than that. Certain passages in

it constitute a sharp challenge to those in this

country who are working in the same spirit as Dr.

Kantorowicz and for the same ends. For as they

read his pages they cannot but ask themselves

whether it must of necessity be true that organisation

for peace and friendship is always less effective

than organisation for antagonism and war.

In a passage quoted on an earlier page of this

issue Dr. Kantorowicz shows how the German

Navy League, founded by the high priest of the

German Navy, Admiral von Tirpitz, secured in ten

years a membership of over 1,000,000, with 5,000

local committees, and raised the circulation of its

journal, "The Fleet," to 480,000. Anti-British

propaganda, it is added, was the main end of its

activities. That was in the decade 1898-1908. Today

Tirpitzism and most of what it stood for are

dead in Germany, despite the crusades of Hitler

and his Nazis, for Tirpitzism represented the ambition

of a State already strong for still fuller

domination, while Hitlerism represents psychologically

the revolt of a State defeated and humiliated

against the consequences of defeat. But there

is enough resemblance in the spirit behind the two

movements to serve as warning of the need for

exerting every effort to counter the new challenge

of the German Nationalists of 1931.

How can that be done? It can only be done

effectively by Germans themselves, but the Germans

anxious to do it will only hold their own if they

get reasonable support from the foes of aggressive

Nationalism everywhere. The alternative to

aggressive Nationalism is a practical internationalism,

such as can be expressed to-day through the

League of Nations alone. That alternative, fortunately,

exists not merely on paper but in reality.

Equality in co-operation under the League

Covenant gives every nation its right to live its

life and its chance to live it. But the Covenant

itself, after all, is nothing more than paper unless

it is made something more. The institution of

which the Covenant is the charter must be charged,

and perpetually recharged, with life by the inflexible

and unmistakably expressed resolves of the people

in every land who believe the world should be

organised on a Covenant basis.

That, of course, is an old, almost a hackneyed,

doctrine, and the obvious comment on it in this

connection is that so far as Germany is concerned

it is for Germans to do the charging. It is. But

the people of one country may well be stimulated

by the people of another. Let us get back for a

moment to Dr. Kantorowicz again. He is describing,

and approving, the British attitude towards

international affairs. That, of course, leads

straight to the League of Nations, of which the

writer observes, "Of necessity it is a League of

Governments, and consequently organisations were

created in each country in order to dispose the

populations, and through them the governments,

to view the League with favour. By far the most

important organisation of this kind is the English

League of Nations Union, a body which embraces

every political party and is supported by almost

all the leading politicians. It is one of the most

important factors in English public life, and no

Government is beyond the reach of its influence.

A few further facts are cited, and then comes the

comment, "We have here another palpable example

of the truth about the alleged insular egoism of the

English. The truth is that international feeling is

not weaker in England than elsewhere, but is, in

fact, ten times more powerful than in all the nations

of the world put together."

Now this book, it is worth remembering, was

originally written in German by a German, and it

was for the instruction of German readers, not for

the gratification of British (not merely English)

members of the League of Nations Union, that the

salient facts about the Union are cited. There is plain

proof there that purely national work for the League

can and does have definite effect far beyond the

national frontiers. Germany is to be convinced, so

far as Dr. Kantorowicz can convince her, of the good

faith and breadth of sympathy of Great Britain by

a demonstration of the success of the British

League of Nations Union.

It is well to be reminded of this at a time when

all minds are turned, or should be, on next year's

Disarmament Conference. Why organise, and

arrange meetings, in this country in favour of

disarmament, it is sometimes asked. This country is

already converted. It has reduced its Army to the

level of a police force. It has entered into two

Naval Limitation Agreements in ten years. It is

other countries that need convincing, not ours. As

to that, it would not be impossible to find quarters

in Great Britain where the work of conversion

might still be pursued. But the essential and

fundamental fact is that news to-day knows no frontiers.

British opinion about disarmament is assessed and

interpreted in the papers of Paris and Rome, of

Berlin and Prague and Washington and Madrid.

Keenness or coolness in London tends to find its

reflection in a corresponding keenness or coolness in

those capitals. All sorts of other factors are at

work as well, but that factor bulks large among

them. From the work so largely cited we may

learn how British opinion is cited abroad, and from

the same pages we may cull the example of von

Tirpitz and his Navy League propaganda as at once

an example and a challenge. Can we organise as

effectively as that for the League of Nations or not?

[*HN.*]

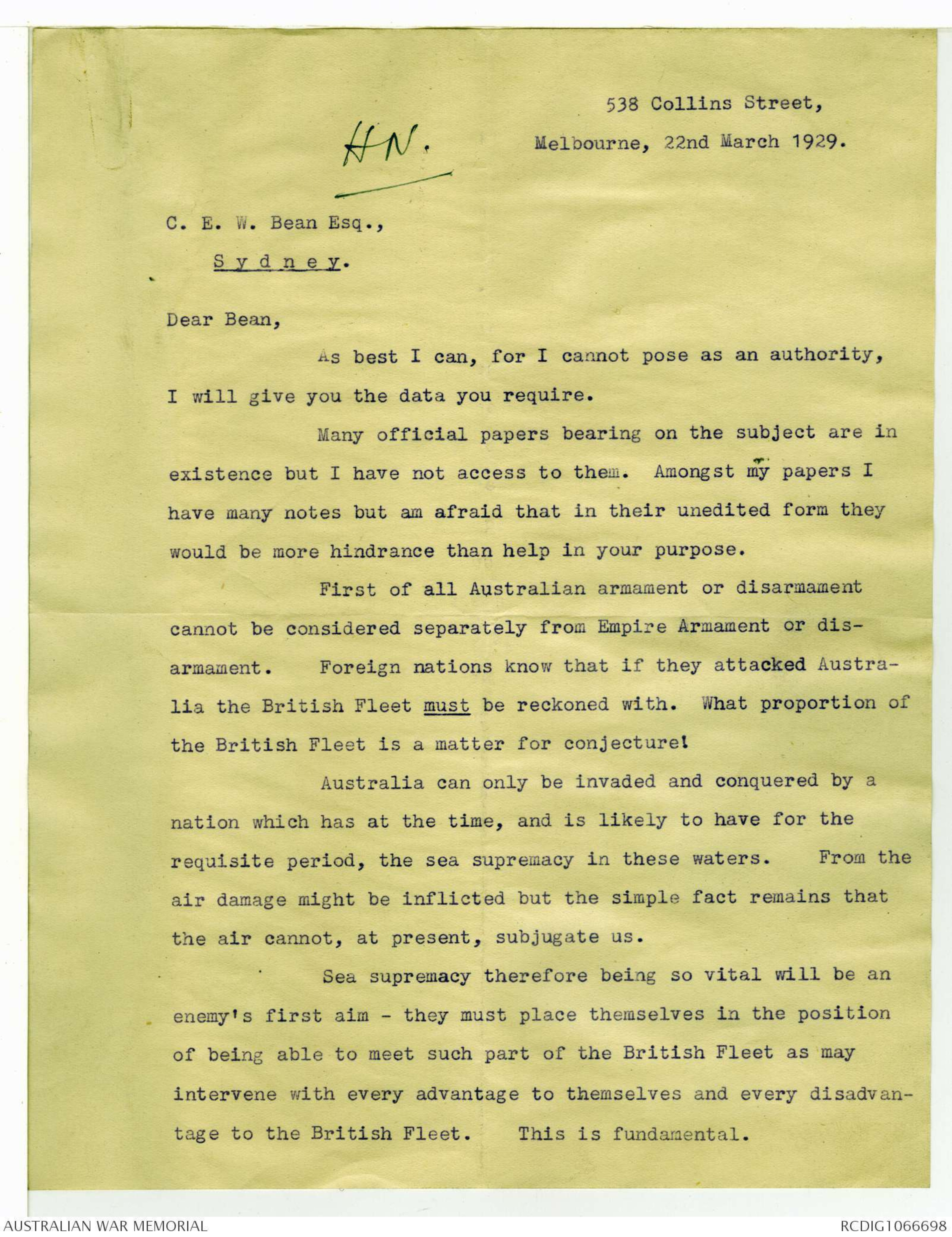

538 Collins Street,

Melbourne, 22nd March 1929.

C. E. W. Bean Esq.,

Sydney.

Dear Bean,

As best I can, for I cannot pose as an authority,

I will give you the data you require.

Many official papers bearing on the subject are in

existence but I have not access to them. Amongst my papers I

have many notes but am afraid that in their unedited form they

would be more hindrance than help in your purpose.

First of all Australian armament or disarmament

cannot be considered separately from Empire Armament or disarmament.

Foreign nations know that if they attacked Australia

the British Fleet must be reckoned with. What proportion of

the British Fleet is a matter for conjecture!

Australia can only be invaded and conquered by a

nation which has at the time, and is likely to have for the

requisite period, the sea supremacy in these waters. From the

air damage might be inflicted but the simple fact remains that

the air cannot, at present, subjugate us.

Sea supremacy therefore being so vital will be an

enemy's first aim - they must place themselves in the position

of being able to meet such part of the British Fleet as may

intervene with every advantage to themselves and every disadvantage

to the British Fleet. This is fundamental.

-2-

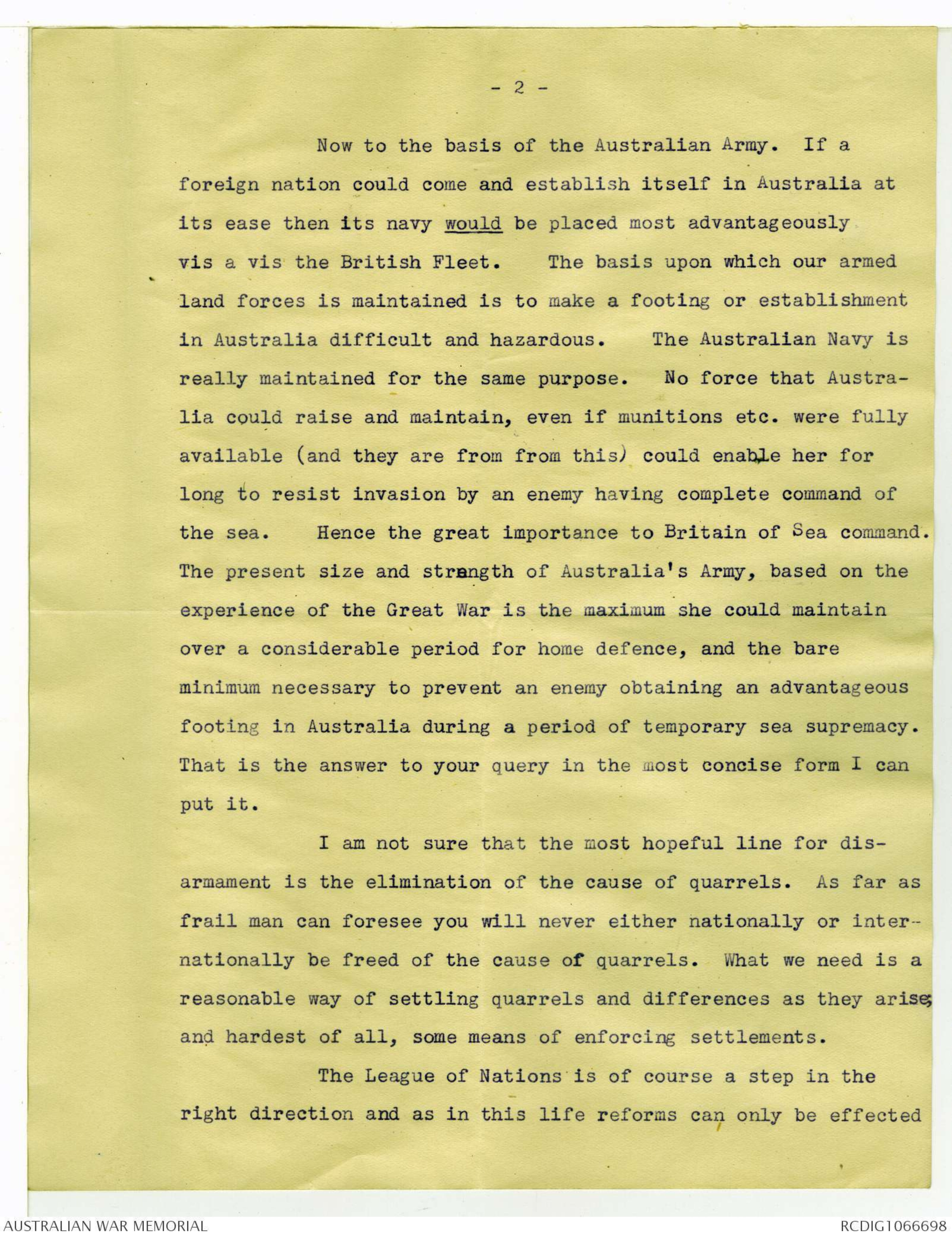

Now to the basis of the Australian Army. If a

foreign nation could come and establish itself in Australia at

its ease then its navy would be placed most advantageously

vis a vis the British Fleet. The basis upon which our armed

land forces is maintained is to make a footing or establishment

in Australia difficult and hazardous. The Australian Navy is

really maintained for the same purpose. No force that Australia

could raise and maintain, even if munitions etc. were fully

available (and they are from from this) could enable her for

long to resist invasion by an enemy having complete command of

the sea. Hence the great importance to Britain of Sea command.

The present size and strength of Australia's Army, based on the

experience of the Great War is the maximum she could maintain

over a considerable period for home defence, and the bare

minimum necessary to prevent an enemy obtaining an advantageous

footing in Australia during a period of temporary sea supremacy.

That is the answer to your query in the most concise form I can

put it.

I am not sure that the most hopeful line for disarmament

is the elimination of the cause of quarrels. As far as

frail man can foresee you will never either nationally or internationally

be freed of the cause of quarrels. What we need is a

reasonable way of settling quarrels and differences as they arise;

and hardest of all, some means of enforcing settlements.

The League of Nations is of course a step in the

right direction and as in this life reforms can only be effected

Deb Parkinson

Deb ParkinsonThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.