Charles E W Bean, Diaries, AWM38 3DRL 606/262/1 - 1916 - 1934 - Part 1

AWM38

Official History,

1914-18 War: Records of C E W Bean,

Official Historian.

Diaries and Notebooks

Item number: 3DRL606/262/1

Title: Folder, 1916 - 1934

Covers various subjects, including the origins of

the war and wartime propaganda, and includes

Bean's notes, cuttings, speeches (eg by W M

Hughes) and letters from Sir Brudenell White

and J L Treloar.

AWM38-3DRL606/262/1

Misc. - incl. Origins of the War. No. 262.

1st SET. AWM 38 3 DRL 606 ITEM [[355?]]

DIARIES AND NOTES OF C. E. W. BEAN

CONCERNING THE WAR OF 1914 - 1918

THE use of these diaries and notes is subject to conditions laid down in the terms

of gift to the Australian War Memorial. But, apart from those terms, I wish the

following circumstances and considerations to be brought to the notice of every

reader and writer who may use them.

These writings represent only what at the moment of making them I believed to be

true. The diaries were jotted down almost daily with the object of recording what

was then in the writer’s mind. Often he wrote them when very tired and half asleep;

also, not infrequently, what he believed to be true was not so —but it does not

follow that he always discovered this, or remembered to correct the mistakes when

discovered. Indeed, he could not always remember that he had written them.

These records should, therefore, be used with great caution, as relating only what

their author, at the time of writing, believed. Further, he cannot, of course, vouch

for the accuracy of statements made to him by others and here recorded. But he

did try to ensure such accuracy by consulting, as far as possible, those who had

seen or otherwise taken part in the events. The constant falsity of second-hand

evidence (on which a large proportion of war stories are founded) was impressed

upon him by the second or third day of the Gallipoli campaign, notwithstanding that

those who passed on such stories usually themselves believed them to be true. All

second-hand evidence herein should he read with this in mind.

16 Sept., 1946. C. E. W. BEAN.

Origins of the War

War time propaganda & lies

Mr Hughes's Speeches in England, 1916

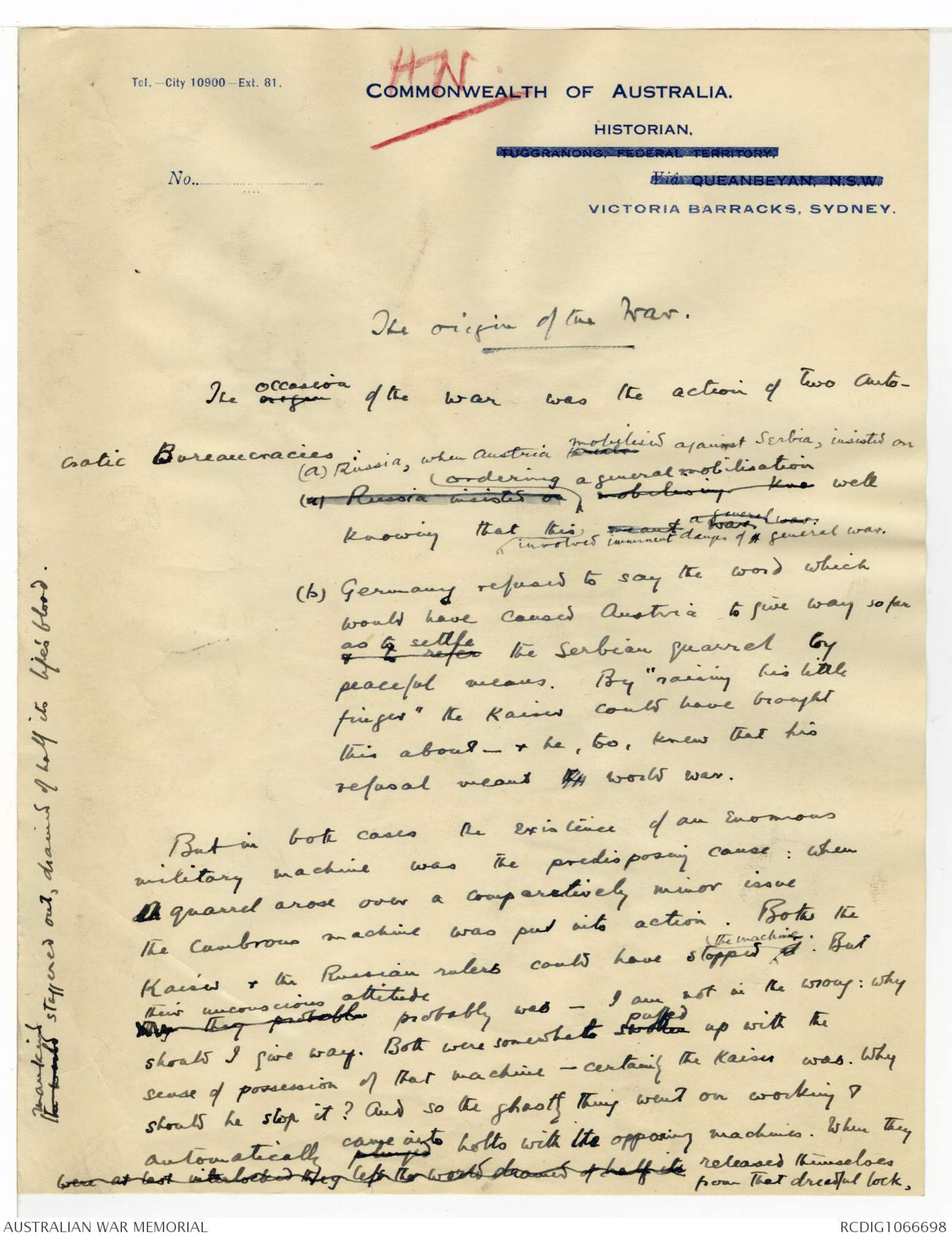

[*HN.*]

Tel.—City 10900—Ext. 81.

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA.

HISTORIAN,

No......TUGGRANONG FEDERAL TERRITORYVia QUEANBEYAN, N.S.W.

VICTORIA BARRACKS, SYDNEY.

The origin of the War.

The origin occasion of the war was the action of two autocratic

Bureaucracies:

(a) Russia, when Austria threaten mobilised against Serbia, insisted on(a) Russia insisted on ^ordering a general mobilisation mobilising kno well

knowing that this meant war a general war: ^involved imminent danger of a general war.

(b) Germany refused to say the word which

would have caused Austria to give way so far& to refer as to settle the Serbian quarrel by

peaceful means. By "raising his little

finger” the Kaiser could have brought

this about - & he, too, knew that his

refusal meant the world war.

But in both cases the existence of an enormous

military machine was the predisposing cause: when

a quarrel arose over a comparatively minor issue

the cumbrous machine was put into action. Both the

Kaiser & the Russian rulers could have stopped it ^the machine. Butthey they probabl their unconscious attitude probably was - I am not in the wrong: why

should I give way. Both were somewhat swollen puffed up with the

sense of possession of that machine - certainly the Kaiser was. Why

should he stop it? And so the ghastly thing went on working &

automatically plunged came into holts with the opposing machines. When theywere at last interlocked they left the world drained of half its released themselves

from that dreadful lock,

[*The world mankind staggered out, drained of half its life’s blood.*]

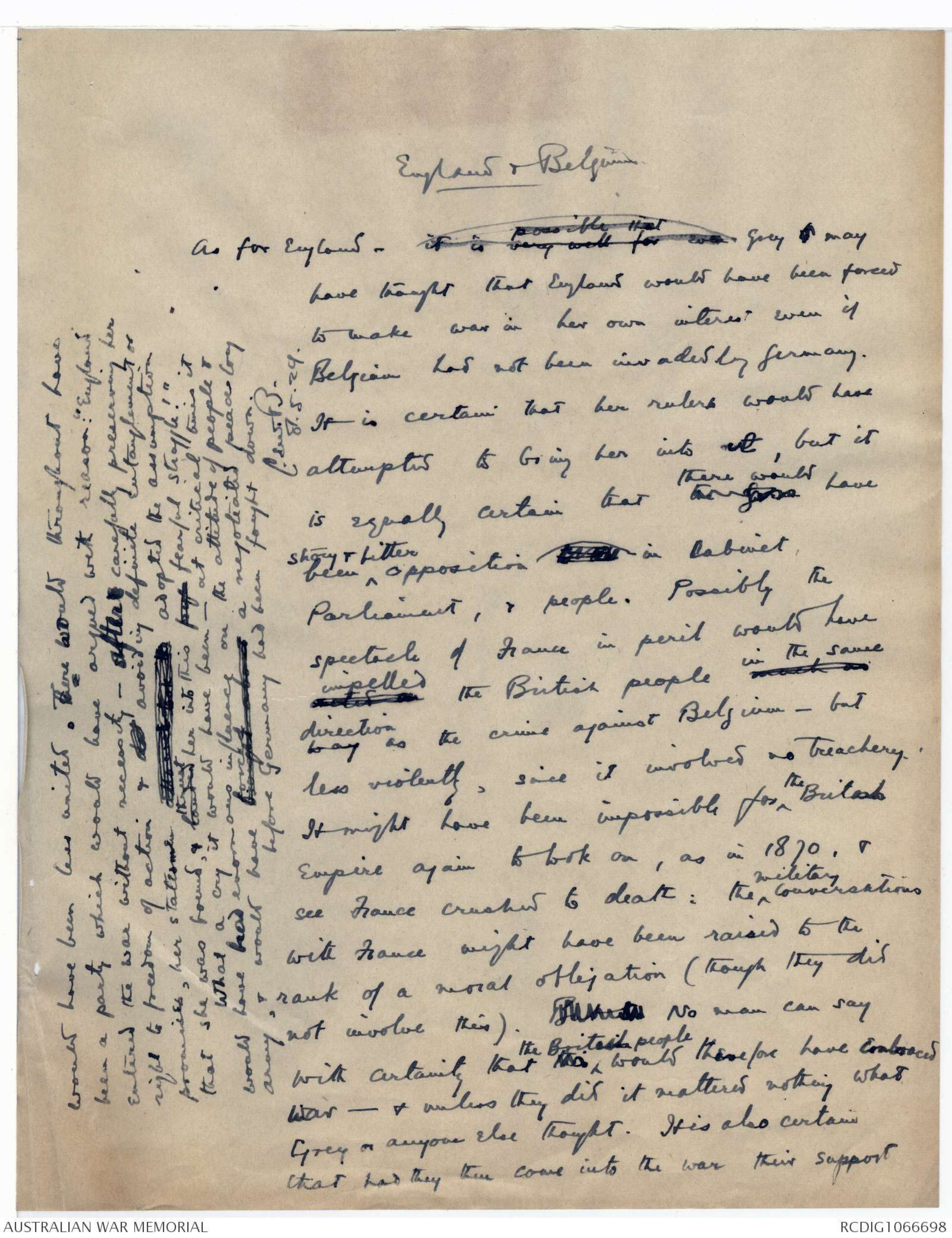

England & Belgium

As for England - it is very well for even possibly that for Grey xx may

have thought that England would have been forced

to make war in her own interest even if

Belgium had not been invaded by Germany.

It is certain that her rulers would have

attempted to bring her into it, but it

is equally certain that the Germs there would have

been ^strong & bitter opposition xxxx in Cabinet,

Parliament, & people. Possibly the

spectacle of France in peril would haveacted on impelled the British people much as in the sameway direction as the crime against Belgium - but

less violently, since it involved no treachery.

It might have been impossible for ^the British

Empire again to look on, as in 1870, &

see France crushed to death: the ^military conversations

with France might have been raised to the

rank of a moral obligation (though they did

not involve this). But really No man can say

with certainty that this ^the British people would therefore have embraced

war - & unless they did it mattered nothing what

Grey or anyone else thought. It is also certain

that had they then come into the war their support

would have been less united. There would throughout have

been a party which would have argued with reason: "England

entered the war without necessity - after r carefully preserving her

right to freedom of action & def avoiding definite entanglement or

promises, her statesmen all went & took its adopted the assumption

that she was bound, & landed thrust her into this perf fearful struggle!"

What a cry it would have been - at critical times it

would have had enormous influence on the attitude of people &

army, & would have brought about forced a negotiated peace long

before Germany had been fought down.

C.E.W.B.

87.5.29*]

Considerations concerning War origins.

[*(Authorities for facts:

Life of Lord Carnock.

July 1914.

Mr Holman's lecture on

Gooch & Temperley)*]

The difficulty tt confronted

Grey was: he believed isolation

wd lead to end in war (or wd not

prevent it) & that the war wd

be disastrous, England being

friendless.

He knew tt / Govt & people

wd not agree to alliance w France (& Russia)

- unless he raised the German bogey - wh he wd not

dream of doing, & wh in itself wd bring war.

He therefore got England to commit herself as

far as she wd commit herself - i.e. to suppt France

in a war if, when the occasion came, ^she considered the war ws

unjustly forced upon France. He could never promise

more - bec. the English people (not merely Lulu Harcourt) wouldn't

stand it. Lulu represented a very definite reality.

Those who think Grey wrong have to prove that

England would have been wiser to remain isolated – it

would not have stopped the a great war, but she wd not have

been in it: Would her positn really have been better

afterwards, morally & physically?

But it is urged tt Grey shd have made his

threat - explained where England stood - on July 25

or 26 instead of on Aug 1. We now know tt this

might have stopped / war - / Kaiser might have

instructed his ambassador in Vienna as he did

on Aug 1 to bring pressure on Austria.

But Grey ^(tho' not some of his advisers) believed tt / Kaiser's Germ. Govt's professions tt

it was bringing exerting pressure on Austria were sincere.

Actually, we now know, the Kaiser was anxious to

prevent war. Grey did not realise how much / Kaiser's

attitude had changed since 1912 - & that having given

a promise of support gn to Austria was like hobbles

on his feet - his vanity wd not allow him to shake off

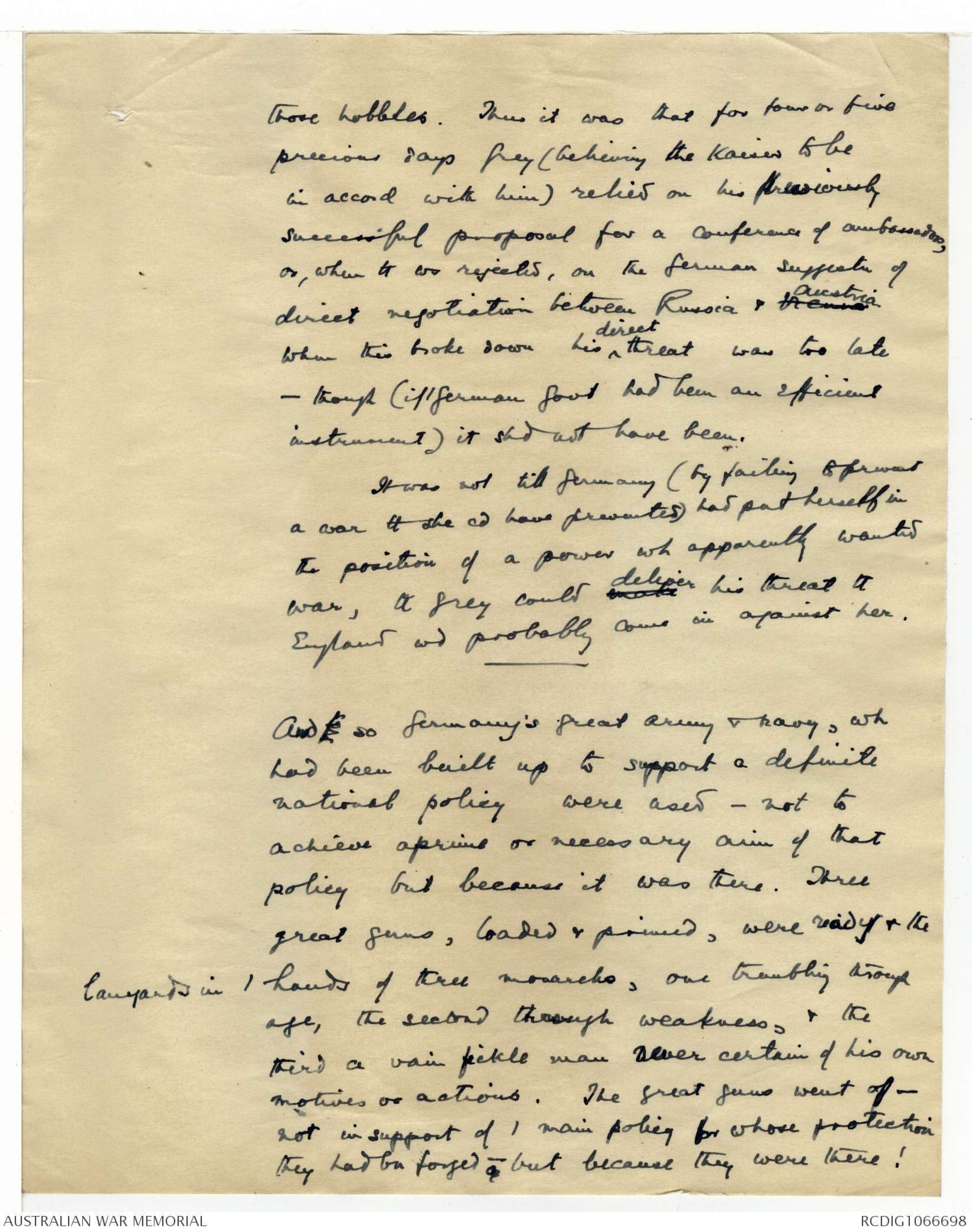

those hobbles. Thus it was that for four or five

precious days Grey (believing the Kaiser to be

in accord with him) relied on his previously

successful proposal for a conference of ambassadors,

or, when tt ws rejected, on the German suggestn of

direct negotiation between Russia & Vienna Austria.

When this broke down his ^direct threat was too late

- though (if / German Govt had been an efficient

instrument) it shd not have been.

It was not till Germany (by failing to prevent

a war tt she cd have prevented) had put herself in

the position of a power wh apparently wanted

war, tt Grey could make deliver his threat tt

England wd probably come in against her.

And / so Germany's great army & navy, wh

had been built up to support a definite

national policy were used - not to

achieve a prime or necessary aim of that

policy but because it was there. Three

great guns, loaded & primed, were ready & the

lanyards in / hands of three monarchs, one trembling through

age, the second through weakness, & the

third a vain fickle man never certain of his own

motives or actions. The great guns went off -

not in support of / main policy for whose protection

they had bn forged & - but because they were there!

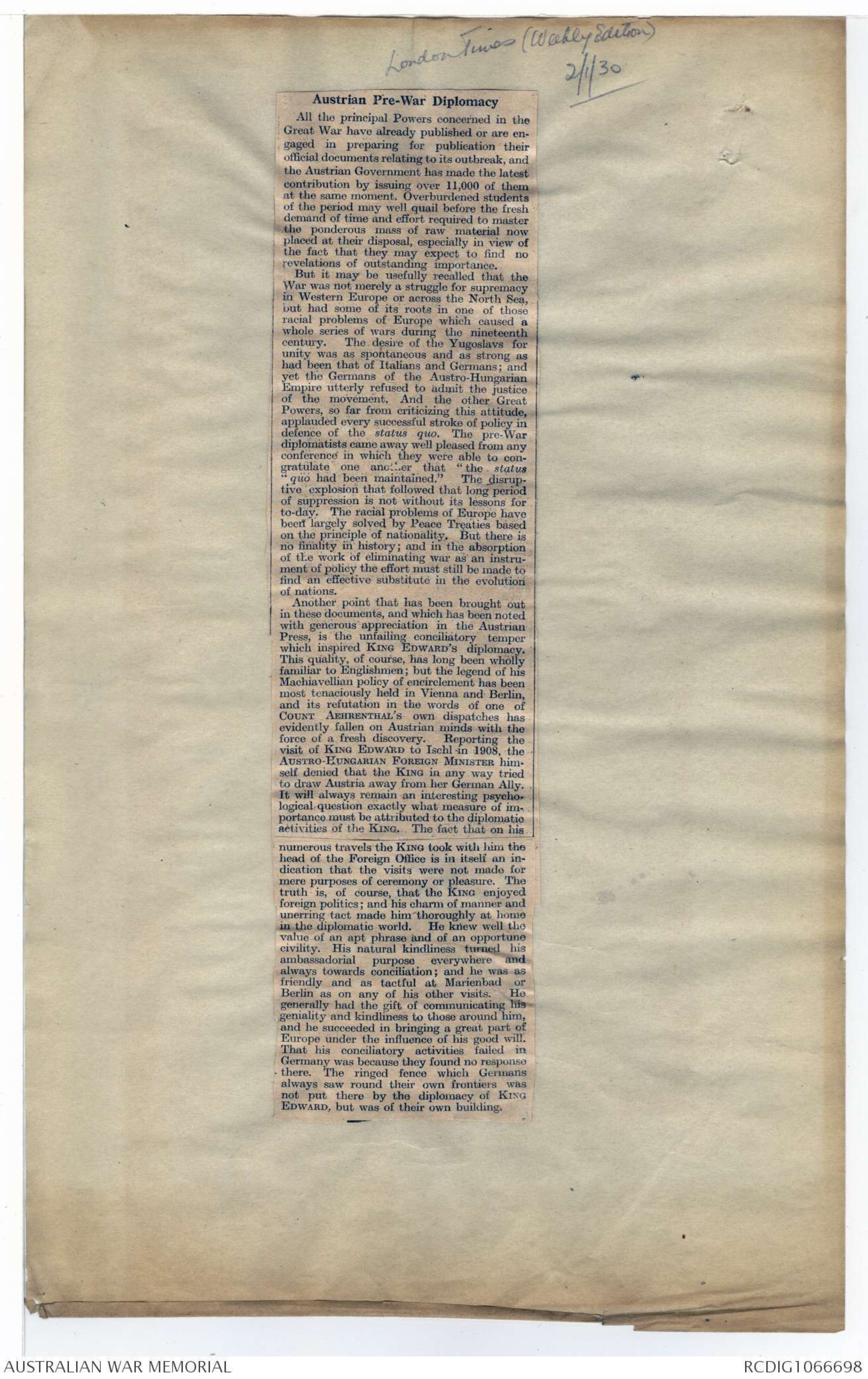

London Times (Weekly Edition)

2/1/30

Austrian Pre-War Diplomacy

Newspaper article - see original document

The Times Literary Supplement

1/8/29

HERR LUDWIG ON JULY, 1914

Newspaper article - see original document

The Times

Literary Supplement

12/3/31

COMING OF THE WAR

Newspaper article - see original document

Deb Parkinson

Deb ParkinsonThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.