Charles E W Bean, Diaries, AWM38 3DRL 606/253/1 - 1918 - 1939 - Part 19

consisted of rolling plateaux similar to Salisbury

Plain. We could not fail to be observed & it was

a subject of general comment.

Reaching the road we kept in open

country on its left hand side but not in

the shadow of the trees. It was noticed that

38, 39 & 40 battalions trailed on behind

us, making a very long & very visible column.

After marching for some ¾ of an hour

we reached a steep declivity where we

rendezvoused with 3 Tanks. There was awll kept well kept German cemetery on the right of the

road. We continued our way with the

tanks leading with the intention of reaching

a cross road just beyond La Flêche by 10 pm.

It was distinctly understood (& I wish to emphasize

this) that we should encounter no opposition

as far as this cross road, hence column of route).

At this point we were to assume open order.

We crossed the old 1916 line soon

after 9 pm it now being dark & saw ahead

on our left a large abandoned timber

dump. After passing this, one tank

3

took up a position on the left flank as a sort of

flank guard & a platoon under Lieut. R.J.

Smith was detached for the same purpose.

All this time the tanks were making

great noise, the xxx writer marching at the

tail of the 2nd tank & at the front of the

37th Battalion.

On reaching the houses of La Flêche

in the right of the road there came a

sudden burst of highly concentrated machine

gun fire & which was directed on the furthermost

corner of these buildings making the road

practically impassable. The writer escaped

by keeping in the lee of the tank. Those following

immediately, having no cover, caught the

full blast & many casualties ensued at

this point. But many got by & the march

was resumed.

Almost immediately the leading

tank ran on a road mine & was

disabled completely blocking the road.

The battalion was now in considerably

confusion those behind pressing on & those

before wanting to get back & no one was in

control. Simultaneously the enemy lighted

many ground flares on the road & used

all sorts of fireworks which came right

over & illuminated the whole scene like

day. Fortunately the enemy fire was

frightfully erratic & high but casualties

were occurring with unpleasant frequency.

Many men got into a shallow ditch on

the right of the road, full of barbed wire,

but for some inexplicable reason not

enfiladed by M.G. fire. Others, the writer

included, sought such shelter as the numerous

trees afforded, & he identified no fewer than

10 M.G. guns concentrated on the stretch of

road from La Flêche to the leading tank -

less than 100 yards.

Meanwhile the enemy attacked the

5

rear of the column (40th Batt) with low-flying

planes & did much damage & causing the

whole column to become very badly [bunshed?].

About this time Lt. Col. Knox Knight made

his way, unaccompanied, from the neighbourhood

of the rear of his battn along the centre of

the road, now entirely clear of troops except

such as were casualties, & by a miracle

was uninjured. He reached the block in

the road & was endeavouring to straighten

out the mess when he was struck by what

the writer believed to be an anti-tank

rifle bullet which took off the back of his

head.

All this time the noise & confusion were

perfectly appalling & it seemed that no one

could ever escape.

However, there came a lull in

the firing & many men, acting entirely

on their own initiative, struck across the

fields towards Framerville & made an

improvised defensive flank.

Here we remained some 2 hours until

orders arrived from Brigade to withdraw.

This we did along the road in artillery

formation quite unmolested in any way.

We took up a position in the old 1916

line & remained there all the next day,

being heavily shelled with gas & H.E.

The whole show had been a most

complete fiasco, & many valuable lives lost.

It is interesting to note this. Just before

starting out an officer asked Col Knox Knight

(in the writers hearing) what he thought about it. He looked more

grave than usual & said words to this

effect "It is either a V.C ^Victoria Cross, or a wooden cross

for me" The writer never again heard him

speak.

Lieut N.G. MacNicol was Battn Scout Officer

at this time & as such was far ahead with

O.C. Tanks. The writer believes he received

a slight wound & was evacuated from the Battn.

The writer knew MacNicol very well especially

in the early days when they were tent mates

together.

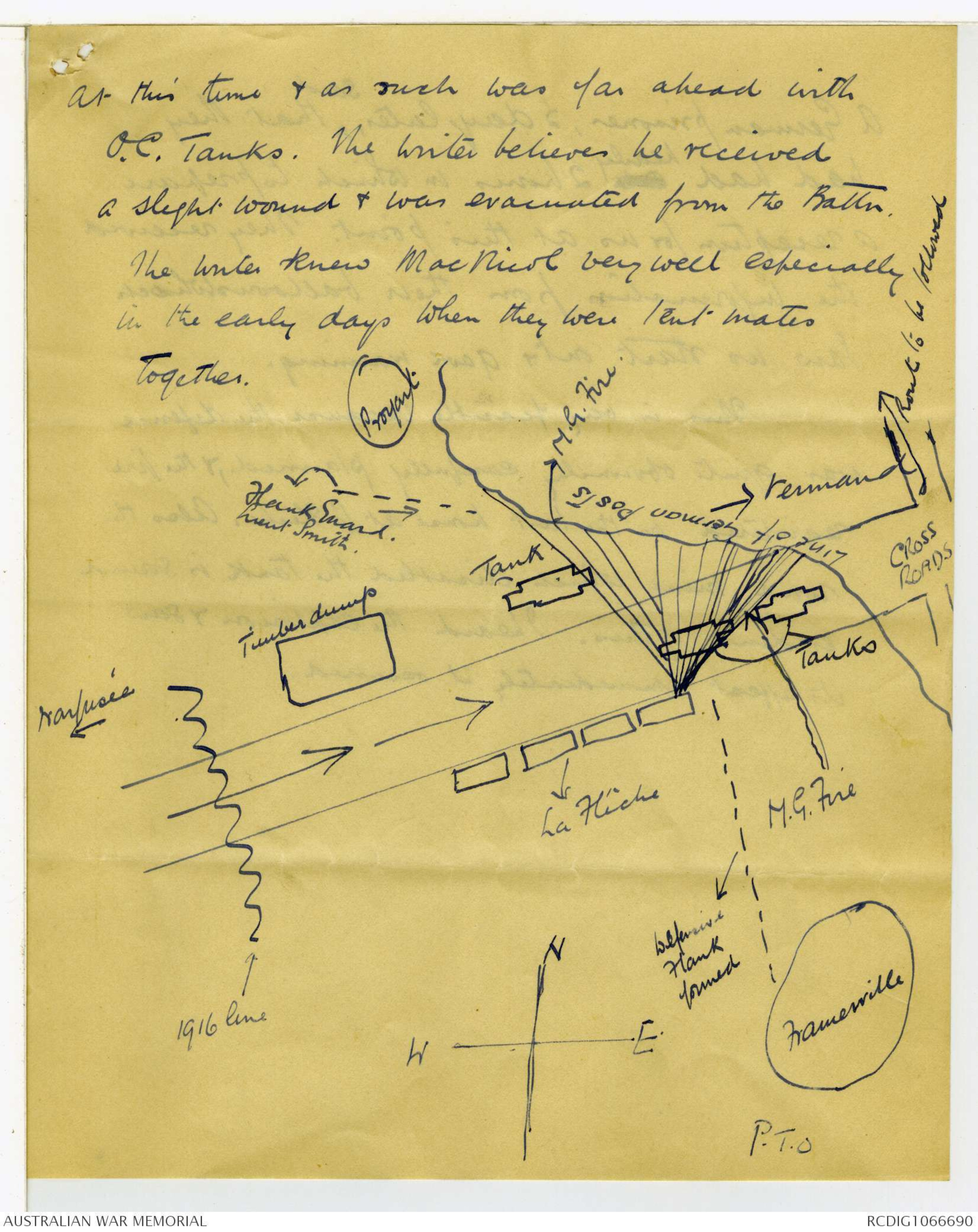

Diagram - see original document

A German prisoner, 2 days later, ^said that they

had had over nearly 2 hours in which to prepare

a reception for us at this point. They received

the information from their balloons which

saw us start out & gave warning.

This is very feasible because the defence

was quite obviously carefully planned, & the fire

registered on the last house at La Flêche. Also the

road mine which disabled the tank is sound

evidence of this. I heard the explosion & saw

its effect immediately it occurred.

[*See Hickey's book

Rolling into Action*]

2

REVEILLE November 1, 1933

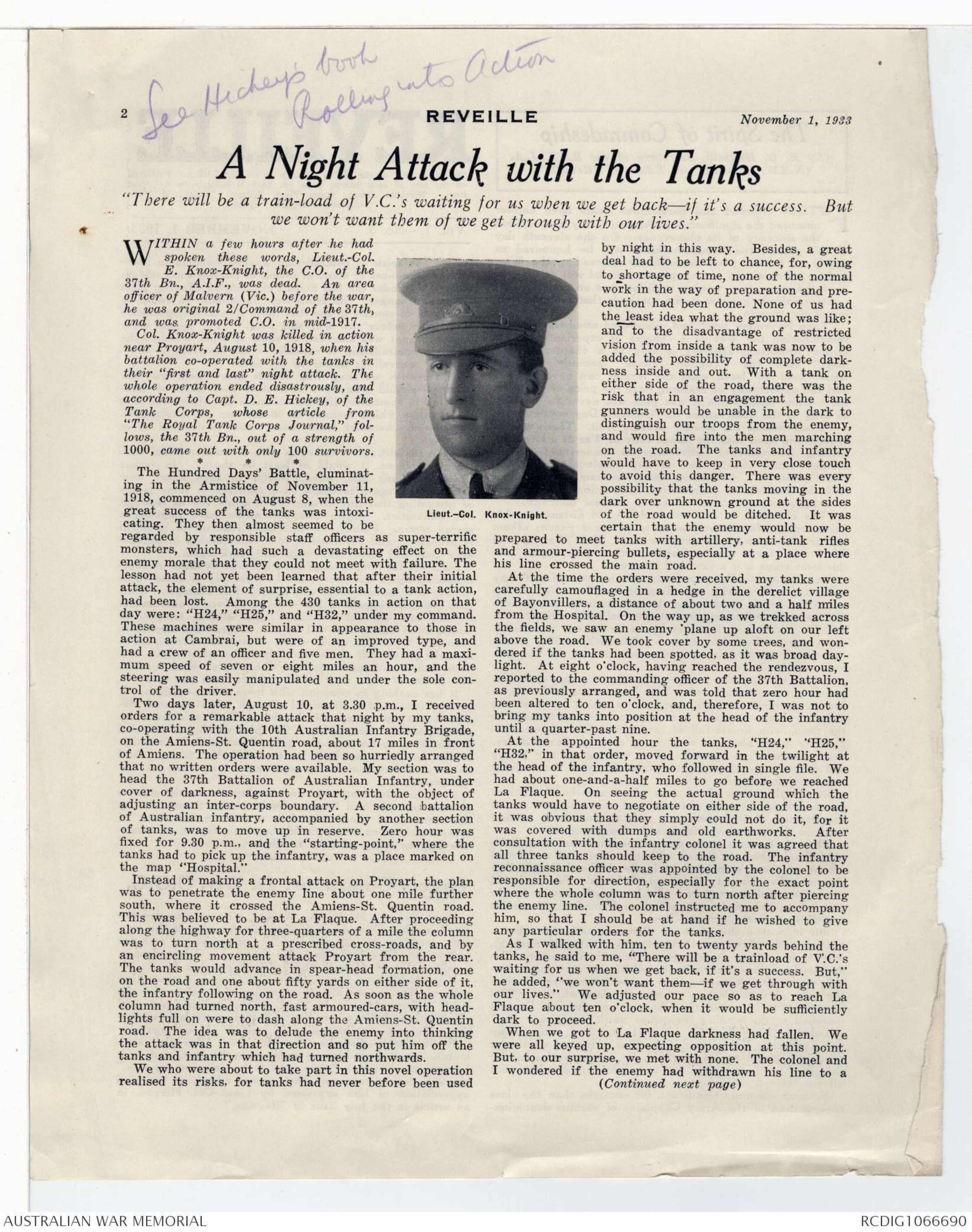

A Night Attack with the Tanks

"There will be a train-load of V.C.'s waiting for us when we get back—if it's a success. But

we won't want them of we get through with our lives."

WITHIN a few hours after he had

spoken these words, Lieut.Col.

E. Knox-Knight, the C.O. of the

37th Bn., A.I.F., was dead. An area

officer of Malvern (Vic.) before the war,

he was original 2/Command of the 37th,

and was promoted C.O. in mid-1917.

Col. Knox-Knight was killed in action

near Proyart, August 10, 1918, when his

battalion co-operated with the tanks in

their “first and last” night attack. The

whole operation ended disastrously, and

according to Capt. D. E. Hickey, of the

Tank Corps, whose article from

“The Royal Tank Corps Journal,” follows,

the 37th Bn., out of a strength of

1000, came out with only 100 survivors.

The Hundred Days' Battle, culminating

in the Armistice of November 11,

1918, commenced on August 8, when the

great success of the tanks was intoxicating.

They then almost seemed to be

regarded by responsible staff officers as super-terrific

monsters, which had such a devastating effect on the

enemy morale that they could not meet with failure. The

lesson had not yet been learned that after their initial

attack, the element of surprise, essential to a tank action,

had been lost. Among the 430 tanks in action on that

day were: “H24,” “H25,” and “H32,” under my command.

These machines were similar in appearance to those in

action at Cambrai, but were of an improved type, and

had a crew of an officer and five men. They had a maximum

speed of seven or eight miles an hour, and the

steering was easily manipulated and under the sole

control of the driver.

Two days later, August 10, at 3.30 p.m., I received

orders for a remarkable attack that night by my tanks,

co-operating with the 10th Australian Infantry Brigade

on the Amiens-St. Quentin road, about 17 miles in front

of Amiens. The operation had been so hurriedly arranged

that no written orders were available. My section was to

head the 37th Battalion of Australian Infantry, under

cover of darkness, against Proyart, with the object of

adjusting an inter-corps boundary. A second battalion

of Australian infantry, accompanied by another section

of tanks, was to move up in reserve. Zero hour was

fixed for 9.30 p.m., and the “starting-point,” where the

tanks had to pick up the infantry, was a place marked on

the map “Hospital.”

Instead of making a frontal attack on Proyart, the plan

was to penetrate the enemy line about one mile further

south, where it crossed the Amiens-St. Quentin road.

This was believed to be at La Flaque. After proceeding

along the highway for three-quarters of a mile the column

was to turn north at a prescribed cross-roads, and by

an encircling movement attack Proyart from the rear.

The tanks would advance in spear-head formation, one

on the road and one about fifty yards on either side of it,

the infantry following on the road. As soon as the whole

column had turned north, fast armoured-cars, with headlights

full on were to dash along the Amiens-St. Quentin

road. The idea was to delude the enemy into thinking

the attack was in that direction and so put him off the

tanks and infantry which had turned northwards.

We who were about to take part in this novel operation

realised its risks, for tanks had never before been used

Photograph - see original document

Lieut.-Col. Knox-Knight.

by night in this way. Besides, a great

deal had to be left to chance, for, owing

to shortage of time, none of the normal

work in the way of preparation and

precaution had been done. None of us had

the least idea what the ground was like;

and to the disadvantage of restricted

vision from inside a tank was now to be

added the possibility of complete darkness

inside and out. With a tank on

either side of the road, there was the

risk that in an engagement the tank

gunners would be unable in the dark to

distinguish our troops from the enemy,

and would fire into the men marching

on the road. The tanks and infantry

would have to keep in very close touch

to avoid this danger. There was every

possibility that the tanks moving in the

dark over unknown ground at the sides

of the road would be ditched. It was

certain that the enemy would now be

prepared to meet tanks with artillery, anti-tank rifles

and armour-piercing bullets, especially at a place where

his line crossed the main road.

At the time the orders were received, my tanks were

carefully camouflaged in a hedge in the derelict village

of Bayonvillers, a distance of about two and a half miles

from the Hospital. On the way up, as we trekked across

the fields, we saw an enemy 'plane up aloft on our left

above the road. We took cover by some trees, and wondered

if the tanks had been spotted, as it was broad daylight.

At eight o'clock, having reached the rendezvous, I

reported to the commanding officer of the 37th Battalion,

as previously arranged, and was told that zero hour had

been altered to ten o'clock, and, therefore, I was not to

bring my tanks into position at the head of the infantry

until a quarter-past nine.

At the appointed hour the tanks, “H24,” “H25,”

“H32,” in that order, moved forward in the twilight at

the head of the infantry, who followed in single file. We

had about one-and-a-half miles to go before we reached

La Flague. On seeing the actual ground which the

tanks would have to negotiate on either side of the road,

it was obvious that they simply could not do it, for it

was covered with dumps and old earthworks. After

consultation with the infantry colonel it was agreed that

all three tanks should keep to the road. The infantry

reconnaissance officer was appointed by the colonel to be

responsible for direction, especially for the exact point

where the whole column was to turn north after piercing

the enemy line. The colonel instructed me to accompany

him, so that I should be at hand if he wished to give

any particular orders for the tanks.

As I walked with him, ten to twenty yards behind the

tanks, he said to me, “There will be a trainload of V.C.’s

waiting for us when we get back, if it's a success. But,”

he added, “we won't want them—if we get through with

our lives." We adjusted our pace so as to reach La

Flaque about ten o'clock, when it would be sufficiently

dark to proceed.

When we got to La Flaque darkness had fallen. We

were all keyed up, expecting opposition at this point.

But, to our surprise, we met with none. The colonel and

I wondered if the enemy had withdrawn his line to a

(Continued next page)

REVEILLE\

Official Journal of the N.S.W. Branch of the R.S.S.I.L.A. Published

on the first of each month, price 3d. (annual subscription 4/-, post

free). Wingello House, Angel Place, Sydney. 'Phone: B 7766.

Telegrams: "Digger," Sydney.

Vol. 7—No.3 NOVEMBER 1, 1933

The Spirit of Comradeship

(By R. D. Hadfield, Secretary of the R.S.S.I.L.A.

(N.S.W. Branch), and Editor of Reveille)

FIFTEEN crowded and momentous years have neither

obscured the significance of Armistice Day nor lessened

the sincerity of its observance. On the eleventh day

of this month the commemoration will be honoured as

widely as in the years immediately succeeding the War,

and far more wisely. Its simple ceremonial will express no

mere deference to a waning tradition, but an emotion that

remains entirely genuine, and a gratitude that has lost nothing

of its strength.

"Each November must find diminished numbers of those

remembering the War as a chapter of experience, and a

larger proportion knowing it only as a chapter of history,"

said the "London Times" recently. "The

latter need to learn what the former can never forget,

and the opportunity of realising both the price of War and

the nobility with which it was paid will never be wanting

so long as the observances on Armistice Day continue.

"These lessons are steadily bearing fruit. There will be

speeches to show that the insane folly of War as a means of

settling International differences is understood at this

moment more clearly than at any previous time in the

world's history. For many reasons statesmen must needs

find the business of transmuting International convictions

into International action a task of colossal difficulty.

"The old clash of interests and the old distrust persist.

Some leaders favour armament to preserve peace; others

favour disarmament to promote it. The "War to end

War" was, for a time, a phrase instinct with hope. At

this later stage is it a vanished illusion?"

This Armistice Day the hope will be revived. It may

still meet with checks and disappointments. Yet, as we

salute the heroic dead at the eleventh hour of the eleventh

day we must feel sanguine that eventually the ultimate aim

will be achieved. Whether by us or by our successors,

there will yet be honoured men whose self-sacrifice means

not merely victory in the war, but victory, in the end,

over war itself.

in part the thoughts suggested by the recurring of Armistice

Day remain unaltered. Year by year its hush can be

for us no lifeless silence, but one in which we hear the

pulse of things eternal. Year by year we pay homage to

the dead, with hearts full of sacred and tender memories.

Year by year, also, we shall help, as they would desire,

their comrades to survive. The wearing of our poppy

will denote a privilege eagerly claimed, rather than a duty

regularly performed.

By this time most of the men who fought have left their

youth behind them, so that, even if they escaped partial

disablement, it is increasingly difficult for them to find

work in this period of widespread unemployment.

These facts make it the more imperative that the admirable

Fund which is linked with the names of a devoted

labour of those associated with the Soldiers' Poppy Day

Appeal—the United Returned Soldiers’ Fund—should

receive our fullest support. To honour those who fought

and fell, to help those who served and survived, are duties

common of every Armistice Day.

But it is true that each of these anniversaries takes a

special colour from the circumstances of its own moment,

and can give to us accordingly its individual message. Today

perhaps there is no leason which we may more usefully

learn from Armistice Day, and adopt in practice, than

the value of comradeship. From the days when the "Old

Contemptibles" crossed the Channel and the first Diggers

marched to the waiting troopships until the "Cease Fire"

sounded on November 11, 1918, the spirit of comradeship

was unshaken. Every page of the War's History, whether it

describes service at sea, on land, or in air, is glorified by

that spirit. It animated not our fighting men alone, but

all who served with them.

Nothing was more significant, for example, than the close

co-operation of the Army Chaplains of various denominations.

The spirit of comradeship worked wonders in those

days. Differences of class, of creed, of politics were seldom

allowed to hinder the full accord of common effort to meet

a common danger. Old feuds were forgotten. It would be

too much, of course, to say that there was no reappearance

of division before the War was over. Yet, in the early

days sufficient was achieved to show of what wonders the

spirit of comradeship is capable. At the front it exercised

its marvellous power to the end.

This month we may well reflect how vastly we—our

country—should gain by a revival of that spirit of comradeship

in something like its old intensity. It is true that

the dangers which menace us to-day are, in major part,

different in character from those which confronted us in

the war.

Then the struggle was begun with a common belief that,

however severe, it would at least be short. In recent

years we have had, unexpectedly, to face many new

crises. And again mistakes have recurred in some minds

of imagining that one strong effort would see us through

our difficulties. Again disappointments have imposed a

severe strain. Plainly, an emotional reaction of goodwill

is necessary, and our need is of a comradeship of persistence

that will work, and wait, and work again.

Such was the temper magnificently shown by those we commemorate

again this year. And the right way of doing them

honour is to imitate what was best in their example. What

that example suggests is less a series of formal agreements

to end our internal difficulties than ending temper, to

which such agreement will be the natural and inevitable

sequel. It is the spirit which shows no recrimination.

It seeks peace, not eschews it. It is the spirit which sets

us to understand and co-operate with people whose interests

and points of view may be far remote from our own.

1t has nothing in common with mere sentimentalism. It

springs from and is sustained through other external circumstances

by an act of the human will reinforced by

divine power. For, if this is the spirit which was revealed

in the War, no less is it the spirit of essential Christianity.

Seldom has its appeal been more needed than to-day. And

never should it come to us with more force than on this

anniversary.

If, in the solemn pause of the morning silence, the citizens

of this Australia and Empire should pledge themselves, by

the memory of those who fell, to live in the spirit of

comradeship, then surely could the true purpose of Armistice

Day be more worthily fulfilled.

Greets Comrades: 1st Div. G.O.C.

Lieut.-General Sir H. B. Walker, who commanded the

1st Australian Division during the greater part of the war,

sent greetings to all old A.l.F. comrades in a letter

written to "Reveille" from his home at Palace Lodge,

Crediton, Devon (Eng.), under date September 5.

It was with keen regret, General Walker said, that other

calls of duty caused him to sever his connection with the

A.l.F. From France, he went to the Italian front, and

afterwards to India, where the work was particularly strenuous.

He was now beginning to feel his old self again.

It was with pleasure that he read "Reveille" each

month, for it kept him in touch with the past, and in it

he saw names which "once used to be daily on my lips."

He was deeply honoured, the general added, at the kind

appreciation of him expressed by Lieut.-Col. Herrod, in

an article in the July issue of "Reveille."

3

November 1, 1933 REVEILLE

point further back, or if the tanks had been observed

moving up in the daylight and he was laying a trap for

us. The night sky in front looked peaceful and calm.

If the enemy were holding a line at this point it seemed

impossible that he should be unaware of our presence,

for the clatter of the tanks on the hard road rent the

stillness of the night. About a quarter of a mile beyond

La Flaque we heard, above the noise of the tanks, the

roar of a ‘plane overhead. Suddenly there was a downward

whizz, a blinding flash, and then a terrific explosion.

The unditching-beam of the rear tank—about ten yards

away—flew up into the air and crashed back. As luck

would have it, this was exactly the spot where the enemy

was holding his line and had a strong point in a large

dump at the side of the road. Other bombs fell.

The noise of the bombing-‘plane had up to this moment

drowned the clatter of the tanks; but now the enemy

was alarmed. He at once put up flares which made the

night as bright as day. In the ghastly light we could

see the poplars and the hedges along the road. Then hell

was let loose! A withering machine-gun fire was opened

on the tanks. The infantry following close behind,

being swept by it, took cover in the ditch on the south

side of the road. The tanks replied with their six-

pounder and machine-guns; but without effect, for no

targets could be seen. The peculiar thing was that there

was not even a flash to aim at. In short rushes the

infantry continued to advance. The enemy had now got

his artillery to bear on us, and shells began to explode

in the road and on either side of it. The noise was terrific.

Machine-gun bullets cracked all round, like a thousand

whips. A war correspondent, who was in a position to

have a full view, described how one of the tanks was

lit up like a blacksmith’s fire by the quantity of bullets

striking it.

After about half-an-hour there was a short lull, except

for desultory firing. The tanks had halted. The colonel

was on the road taking stock of the situation, and I

was hurriedly approaching the rear tank when the tank

commander of “H25” hastened to me with a terrific

[*No 2

Tk*]

wound in his right fore-arm. He was weak from loss of

blood and had been obliged to hand his tank over to the

corporal. It was obvious he could not carry on, and I sent

him back to have his wound dressed. He reported that

the enemy were using anti-tank rifles and armour-piercing

bullets. He told me it was impossible to locate the enemy

machine-guns from inside the tank, and on two occasions

when he had got outside to keep in touch with the infantry

he could see nothing. I immediately returned to the

colonel to tell him that I had lost an officer, and gave him

the information I had received.

The tanks started to move again. Immediately there

was a hurricane of machine-gun fire, and we again took

cover. The night was pitch-black, except for occasional

fares. The infantry, advancing in short rushes along

the side of the road, were being mown down like grass,

and lay where they fell.

At this moment a runner reported that the tanks were

returning. “They haven't got orders to turn, have they?”

the colonel asked me in amazement. I was equally staggered,

and replied, “Certainly not! I’ll go at once and

tell them to keep straight on." “Yes, you must,” he

answered, and, standing erect, urged the infantry on. I

made a dive forward, with my runner, in a hailstorm of

bullets. I heard a choking gasp, and saw the colonel fall

heavily to the ground, two feet away from me. As we

ran the few yards to the tanks my runner’s pack stopped

a bullet. Miraculously, he was not injured. He found

the bullet later in his pack.

I manoeuvred the tanks forward, running from the front

of one to the front of another. I found it no easy job,

because they were so close together. Then, when trying

to stop one from backing into another, I was caught in

[*“O.C. APES.”

Perhaps the most curious military appointment in the British

Empire is that of “O.C. Apes,” at Gibraltar. Officially he is

the “Keeper of the Apes.” A couple of centuries ago the

Spanish had a saying that when the apes died out at Gibraltar

the British would go. The position of “O.C. Apes” was created

to make sure that the monkeys would not die out. This unique

post has always been held by a military officer—usually a gunner

officer quartered at Tracy's Farm, which is situated on the

Diagram -see original document

Upper Rock, where the animals, the last

wild apes in Europe, normally live.

O.C. Apes receives no extra pay or

allowance for this apopintment, and he has

his ordinary military duties to perform, but

he is definitely held responsible for the

safe custody, health and happiness of the

animals. Special shelters have been built

for the apes and the officer in charge has a staff of one man,

who keeps the sheds tidy and sanitary, and places the “rations”

which these animals, being on “the strength” of the garrison,

are allowed. The Governments annual allowance is ₤36.*]

between the two, and had to climb up the back of one

of them to avoid being crushed.

I discovered that the officer in charge of tank “H24”

[*(No1 Tk)*]

had been killed during the first few minutes of the engagement

while walking outside his tank to keep in touch

with the infantry. The tank was perforated on all sides

by armour-piercing bullets, and all the crew, except two,

were wounded. The tank was now in charge of the

second driver, a gunner, who had manoeuvred it for

position to engage enemy machine-guns from what

appeared to be a strong point. It was this manoeuvre

which the infantry mistook and led them to report that

the tank was returning. For his share in the night's

work this gunner was awarded the D.C.M. and promoted

sergeant. Tank “H25,” whose officer and driver had been

severely wounded, had only half its crew uninjured, and

was in charge of a corporal. The officer and crew of

“H32” were all badly shaken and wounded by splinters;

one man, in addition, being gassed by fumes from the

exhaust. The second two tanks had not been able to see

the infantry following, and had turned to get in touch

with them.

My runner and I had got the tanks going forward

again when I heard a shout, and, turning, found the adjutant

of the infantry four or five yards away. He told me

that the colonel had been killed, and that the infantry had

suffered such severe casualties that they were retiring in

extended order. I said the tanks were going forward to

continue the attack. He declared that the infantry were

so disorganised that it would be impossible for them to

follow.

The thought had crossed my mind, “What would the

rest of the operation be like, since just at the start all my

tank crews were wounded and depleted?” Now, without

infantry support, I decided it would be useless for the

tanks to advance further, and I gave the order to retire.

Again, turning them was no easy job. I felt rather like

a wild animal tamer with huge beasts to control. In the

dark the tank crews could not easily understand my

directions, nor hear my voice above the noise. Every

time the tanks moved the enemy machine-guns simply

went mad, and there was a terrific fusilade of bullets.

The tanks had moved back about 150 yards when I

found a revolver being brandished in my face. Replying

to the challenge, I found I was being mistaken for one

of the enemy by an Australian officer at the head of the

second battalion of infantry, which had apparently come

up. So great was the noise of the firing, together with

the clatter of my own tanks on the road, that I had not

heard the approach of the reserve tanks and infantry,

nor could I see them in the dark. My tanks halted while

I explained to him what had happened, and, as we were

(Continued on page 31)

Sandy Mudie

Sandy MudieThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.