Charles E W Bean, Diaries, AWM38 3DRL 606/253/1 - 1918 - 1939 - Part 17

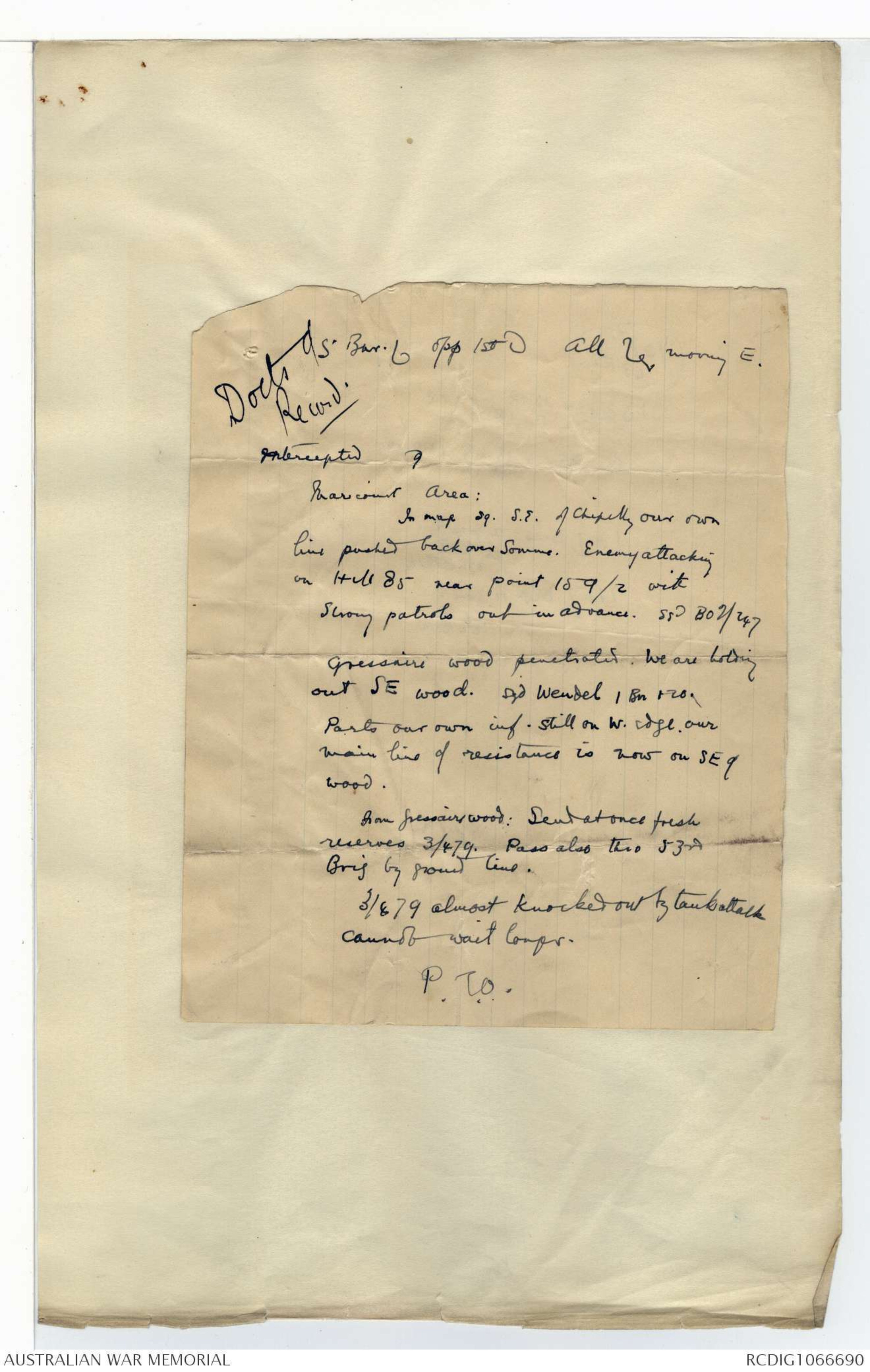

[*Docts of

Record.*]

5 Bar. Division opp 1st D all transport moving E.

Intercepted message

Maricourt area:

In map sq. S.E. of Chipilly our own

line pushed back over Somme. Enemy attacking

on Hill 85 near point 159/2 with

strong patrols out in advance. Sgd B02/247

Gressaire wood penetrated. We are holding

out SE wood. Sgd Wendel 1 Bn 1.20.

Parts our own inf. still on W. edge. our

main line of resistance is now on SE of

wood.

From Gressaire wood: Send at once fresh

reserves 3/479. Pass also thro 53rd

Brig by ground line.

3/479 almost knocked out by tank attack

cannot wait longer.

P.T.O.

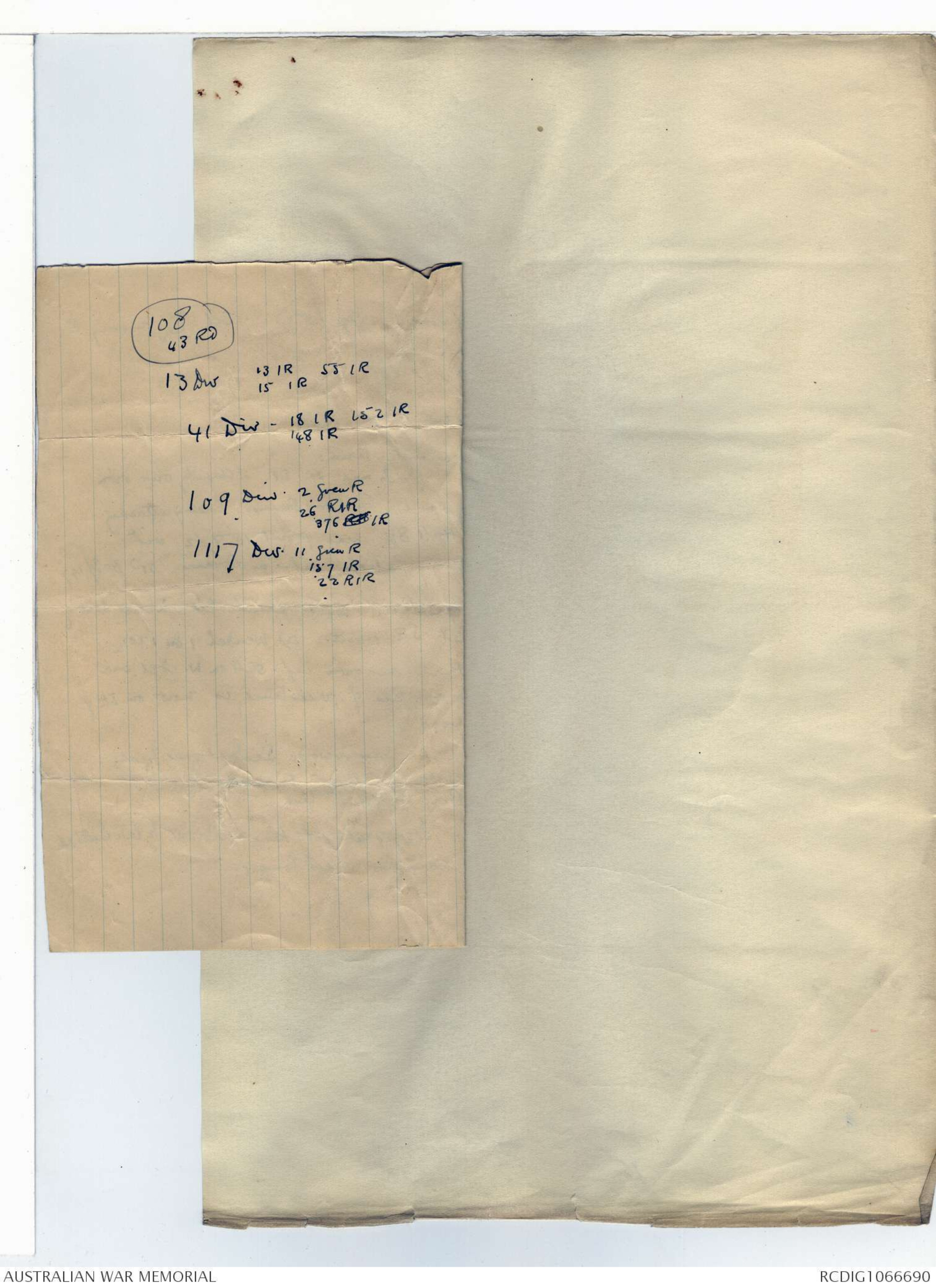

108

43 Rd

13 Div 13 IR 55 IR

15 IR

41 Div - 18 IR 152 IR

148 IR

109 Div. 2 Gren R

26 RIR

376 RIR IR

1117 Div 11 Gren R

157 IR

22 RIR

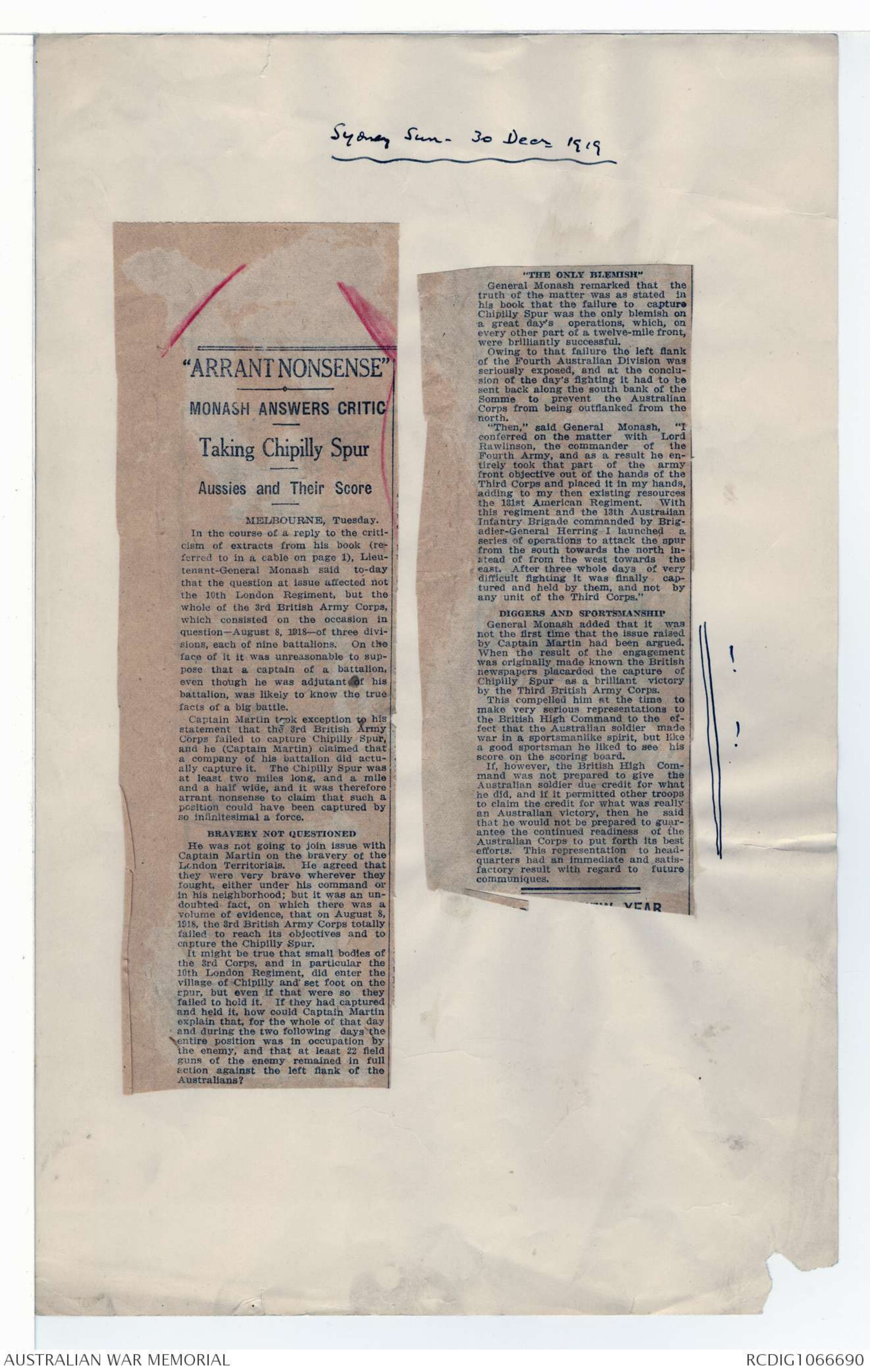

Sydney Sun - 30 Decr 1919

"ARRANT NONSENSE"

MONASH ANSWERS CRITIC

Taking Chipilly Spur

Aussies and Their Score

MELBOURNE, Tuesday.

In the course of a reply to the criticism

of extracts from his book (referred

to in a cable on page 1), Lieutenant-

General Monash said to-day

that the question at issue affected not

the 10th London Regiment, but the

whole of the 3rd British Army Corps,

which consisted on the occasion in

question - August 8, 1918 - of three divisions,

each of nine battalions. On the

face of it it was unreasonable to suppose

that a captain of a battalion,

even though he was adjutant of his

battalion, was likely to know the true

facts of a big battle.

Captain Martin took exception to his

statement that the 3rd British Army

Corps failed to capture Chipilly Spur,

and he (Captain Martin) claimed that

a company of his battalion did actually

capture it. The Chipilly Spur was

at least two miles long, and a mile

and a half wide, and it was therefore

arrant nonsense to claim that such a

position could have been captured by

so infinitesimal a force.

BRAVERY NOT QUESTIONED

He was not going to join issue with

Captain Martin on the bravery of the

London Territorials. He agreed that

they were very brave wherever they

fought, either under his command or

in his neighborhood; but it was an undoubted

fact, on which there was a

volume of evidence, that on August 8,

1918, the 3rd British Army Corps totally

failed to reach its objectives and to

capture the Chipilly Spur.

It might be true that small bodies of

the 3rd Corps, and in particular the

10th London Regiment, did enter the

village of Chipilly and set foot on the

spur, but even if that were so they

failed to hold it. If they had captured

and held it, how could Captain Martin

explain that, for the whole of that day

and during the two following days the

entire position was in occupation by

the enemy, and that at least 22 field

guns of the enemy remained in full

action against the left flank of the

Australians?

"THE ONLY BLEMISH"

General Monash remarked that the

truth of the matter was as stated in

his book that the failure to capture

Chipilly Spur was the only blemish on

a great day's operations, which, on

every other part of a twelve-mile front,

were brilliantly successful.

Owing to that failure the left flank

of the Fourth Australian Division was

seriously exposed, and at the conclusion

of the day's fighting it had to be

sent back along the south bank of the

Somme to prevent the Australian

Corps from being outflanked from the

north.

"Then," said General Monash, "I

conferred on the matter with Lord

Rawlinson, the commander of the

Fourth Army, and as a result he entirely

took that part of the army

front objective out of the hands of the

Third Corps and placed it in my hands,

adding to my then existing resources

the 131st American Regiment. With

this regiment and the 13th Australian

Infantry brigade commanded by Brigadier-

General Herring I launched a

series of operations to attack the spur

from the south towards the north instead

of from the west towards the

east. After three whole days of very

difficult fighting it was finally captured

and held by them, and not by

any unit of the Third Corps."

DIGGERS AND SPORTSMANSHIP

[*!*]

General Monash added that it was

not the first time that the issue raised

by Captain Martin had been argued.

When the result of the engagement

was originally made known the British

newspapers placarded the capture of

Chipilly Spur as a brilliant victory

by the Third British Army Corps.

[*!*]

This compelled him at the time to

make very serious representations to

the British High Command to the effect

that the Australian soldier made

war in a sportsmanlike spirit, but like

a good sportsman he liked to see his

score on the scoring board.

If, however, the British High Command

was not prepared to give the

Australian soldier due credit for what

he did, and if it permitted other troops

to claim the credit for what was really

an Australian victory, then he said

that he would not be prepared to guarantee

the continued readiness of the

Australian Corps to put forth its best

efforts. This representation to headquarters

had an immediate and satisfactory

result with regard to future

communiques.

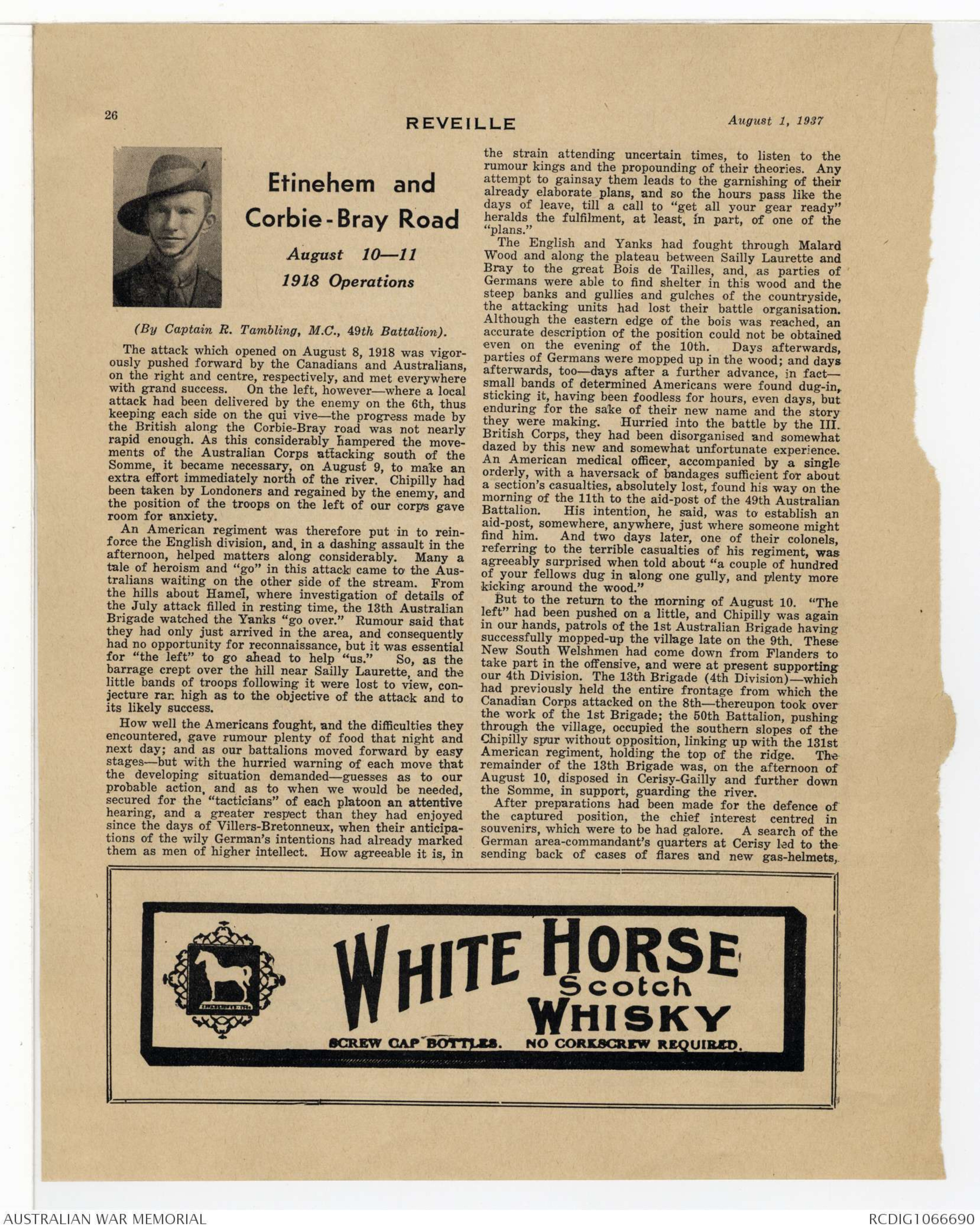

26 REVEILLE August 1, 1937

Etinehem and

Corbie-Bray Road

August 10-11

1918 Operations

Photograph - see original document

(By Captain R. Tambling, M.C., 49th Battalion).

The attack which opened on August 8, 1918 was vigorously

pushed forward by the Canadians and Australians,

on the right and centre, respectively, and met everywhere

with grand success. On the left, however—where a local

attack had been delivered by the enemy on the 6th, thus

keeping each side on the qui vive—the progress made by

the British along the Corbie-Bray road was not nearly

rapid enough. As this considerably hampered the movements

of the Australian Corps attacking south of the

Somme, it became necessary, on August 9, to make an

extra effort immediately north of the river. Chipilly had

been taken by Londoners and regained by the enemy, and

the position of the troops on the left of our corps gave

room for anxiety.

An American regiment was therefore put in to reinforce

the English division, and, in a dashing assault in the

afternoon, helped matters along considerably. Many a

tale of heroism and "go" in this attack came to the Australians

waiting on the other side of the stream. From

the hills about Hamel, where investigation of details of

the July attack filled in resting time, the 13th Australian

Brigade watched the Yanks "go over." Rumour said that

they had only just arrived in the area, and consequently

had no opportunity for reconnaissance, but it was essential

for "the left" to go ahead to help "us." So, as the

barrage crept over the hill near Sailly Laurette, and the

little bands of troops following it were lost to view, conjecture

ran high as to the objective of the attack and to

its likely success.

How well the Americans fought, and the difficulties they

encountered, gave rumour plenty of food that night and

next day; and as our battalions moved forward by easy

stages—but with the hurried warning of each move that

the developing situation demanded—guesses as to our

probable action, and as to when we would be needed,

secured for the "tacticians" of each platoon an attentive

hearing, and a greater respect than they had enjoyed

since the days of Villers-Bretonneux, when their anticipations

of the wily German's intentions had already marked

them as men of higher intellect. How agreeable it is, in

the strain attending uncertain times, to listen to the

rumour kings and the propounding of their theories. Any

attempt to gainsay them leads to the garnishing of their

already elaborate plans, and so the hours pass like the

days of leave, till a call to "get all your gear ready"

heralds the fulfilment, at least, in part, of one of the

"plans."

The English and the Yanks had fought through Malard

Wood and along the plateau between Sailly Laurette and

Bray to the great Bois de Tailles, and, as parties of

Germans were able to find shelter in this wood and the

steep banks and gullies and gulches of the countryside,

the attacking units had lost their battle organisation.

Although the eastern edge of the bois was reached, an

accurate description of the position could not be obtained

even on the evening of the 10th. Days afterwards,

parties of Germans were mopped up in the wood; and days

afterwards, too—days after a further advance, in fact—

small bands of determined Americans were found dug-in,

sticking it, having been foodless for hours, even days, but

enduring for the sake of their new name and the story

they were making. Hurried into the battle by the III.

British Corps, they had been disorganised and somewhat

dazed by this new and somewhat unfortunate experience.

An American medical officer, accompanied by a single

orderly, with a haversack of bandages sufficient for about

a section's casualties, absolutely lost, found his way on the

morning of the 11th to the aid-post of the 49th Australian

Battalion. His intention, he said, was to establish an

aid-post, somewhere, anywhere, just where someone might

find him. And two days later, one of their colonels,

referring to the terrible casualties of his regiment, was

agreeably surprised when told about "a couple of hundred

of your fellows dug in along one gully, and plenty more

kicking around the wood."

But to the return to the morning of August 10. "The

left" had been pushed on a little, and Chipilly was again

in our hands, patrols of the 1st Australian Brigade having

successfully mopped-up the village late on the 9th. These

New South Welshmen had come down from Flanders to

take part in the offensive, and were at present supporting

our 4th Division. The 13th Brigade (4th Division)—which

had previously held the entire frontage from which the

Canadian Corps attacked on the 8th—thereupon took over

the work of the 1st Brigade; the 50th Battalion, pushing

through the village, occupied the southern slopes of the

Chipilly spur without opposition, linking up with the 131st

American regiment, holding the top of the ridge. The

remainder of the 13th Brigade was, on the afternoon of

August 10, disposed in Cerisy-Gailly and further down

the Somme, in support, guarding the river.

After preparations had been made for the defence of

the captured position, the chief interest centred in

souvenirs, which were to be had galore. A search of the

German area-commandant's quarters at Cerisy led to the

sending back of cases of flares and new gas-helmets,

August 1, 1937 REVEILLE 25

"FOR SERVICES RENDERED"

Mr. Frank C. Baker, the author of this story, was an artillery-

man in the A.I.F., and is now a scenario writer at Hollywood,

where his brother "Snowy" Baker, has achieved fame as a polo

player. When Mr. Charles E. Chauvel. the Australian film

producer-director, and nephew of General

Sir Harry Chauvel, arrived in Sydney

from Hollywood on July 12 he brought

with him a story entitled "For Services

Rendered," written by Mr. Frank C.

Baker, for production into a large scale

motion picture in Australia. "For Services

Rendered" is a drama of the World

War, based upon the exploits of the

Australian Lighthorsemen in the desert

campaign between Jerusalem and Damascus.

Says Mr. Baker: "Some of the

major motion picture companies here

have been interested in making it into

a production over this side but I preferred

to sell the rights to Chauvel, as

I feel sure that it will be handled with

more care by him. Anyhow; it is a

purely Australian story, and I feel that if it is to be produced

at all, such production should be by an Australian company

with the employment of Diggers to as large an extent as would

be possible."

Photograph - see original document

(Major Gordon Magee), led a company of the 4th Battalion

up the rugged slopes of Anzac at the Landing.

Captain Gerald Groves, A.D.C. to a former Governor of

Victoria was, until recently, a valued research expert at

the studios.

It is not at all surprising to find so many ex-service

men in the picture business here when one realises that

there are some 230,000 British-born residents in the State

of California, 65,000 of them being in and around Hollywood

alone. There are almost three million people born

within the British Empire now living in the United States,

of which a hefty proportion saw service with the British

Army in the "brawl" of 1914-18.

Most of the rank and file of the British service men

who work as "extras" in pictures are members of the

Hollywood Post of the Canadian Legion, which is one of

the strongest and most alive British Legion Posts in the

U.S. A studio in need of British service men for a

film production has only to 'phone this organisation and

a full company of well-drilled veterans will be at the

studio ready to work within an hour.

Of course, the British Army is not the only one represented

in this Town of Movies. There are organisations

of ex-officers and men of the Imperial Russian Army, the

French Army, as well as the German, Austrian, and

Italian Armies; also smaller groups of almost every

national fighting force on the face of the globe. And

there seems little doubt that every professional soldier of

fortune turns up in Hollywood sooner or later to join

the ranks of the World's Highest Paid Army.

The Australian Force's six-bob a day turned many a

stiff-backed Guardsman a pale green with envy, but such

a scale of wages would be spurned with withering contempt

by the rear rank privates of Hollywood's Army,

whose pay ranges from 30/- to £2 a day when they

shoulder a rifle; and should they have the luck to be

called on by the director to do a "bit"—a bit means

speaking a line, no matter how small, for recording before

the camera—their pay is raised to £5 for the day's work.

Five quid for just saying, "What-oh, Digger!" Not bad,

eh?

But, remember that Hollywood is not always engaged

in making army pictures. So, between wars the movie

warriors have to content themselves with finding jobs

as Irish townfolk, London pedestrians, habitues of waterside

dives, or unshaven beachcombers in other-type

pictures.

One Of Us

(By S.G.C. in the Canadian Legionary)

Have you ever marched the French roads when you're

absolutely beat,

And the poplar trees seem endless in their rows;

When you think you will go crazy watching other fellows'

feet,

And your boots are worn and letting through your toes?

Have you stood waist deep in water day and night until

you freeze,

With just bully beef and biscuit for your fill;

And your kilt all torn to ribbons from the waistband to

the knees,

While your chum lies in the water cold and still?

Have you ever lain in No Man's Land for hours at a time,

Machine gun bullets whistling o'er your head;

Or crawled into the shell holes that are thick with frost

and grime,

When it pays you to be careful — or you're dead?

Have you ever had the courage to climb across the bags,

When the ground in front is being raked with shell;

With the high explosive screaming, tearing everything

to rags,

And the Lewis guns are purring just like hell?

When the fellows keep on dropping by the dozen everywhere,

And you get that awful feeling "I must run;"

But you still continue walking just as though you did not

care,

For your Regiment demands it from each one.

If you've done these things, old fellow, simply knowing

they were right,

Just performing all your duties without fuss;

Then we'll take your hand in our hand with a grip that's

firm and tight,

For you've won your spurs — and are counted

ONE OF US.

Technical advisers on these military pictures—the

fellows who are responsible for the accuracy of technical

details of the production, but whose knowledge is generally

overruled by the director—draw down a salary of

from £15 to £60 a week on the job.

The morning's work was finished, and the "Tommies"

began to stream past us on their way to the studio cafe

for lunch. The colonel watched them intently as they

hurried by us. One of the boys stopped near him to

light a cigarette, which gave my guest an opportunity

of examining the rifle and equipment closely.

As the actor moved away, the colonel turned to me

with a puzzled expression. "That fellow was wearing

the genuine British regulation equipment, and a regulation

Government-marked Lee Enfield. Why, I thought

they used all fake stuff in these pictures. I'd like to

know how they get hold of our army stores over here?"

"Right-o, colonel," I answered. "First of all, let us

get some lunch, and then I'll show you the place that

supplies all the military stores for these film wars—

Hollywood's Q.M. store de-luxe. But now let's eat."

August 1, 1937 REVEILLE 27

together with many German rifles. Medical officers eagerly

sought among the captured aid-posts for drugs and medicines

scarce among our supplies, but which the German

chemists had been able to manufacture in good quantities.

The dead in Cerisy-Gailly were buried. Captured

machine-guns were cleaned and set up as additional defences,

and also mounted for use against aircraft. Our

men, well aware of the use to which they would be able

to put the captured guns, gathered in interested groups

around these trophies. The Lewis gunners posted themselves

as instructors, and eager little gatherings kept

themselves usefully occupied for hours.

The Tank Corps had had the misfortune to lose a few

of their monsters on the downward slopes towards Chipilly,

and the reason for this was to be found among the hedges

on the opposite side of the river, about the road leading

from Chipilly to Etinehem. Here a battery of 77's, good

to look at now that the guns were captured and silent,

lay facing the destroyed tanks; and the men of the Tank

Corps received praise and approbation from the lips of our

men.

Liaison reports about midday on the 10th having showed

that still greater progress must be made just north of the

river, it was arranged that the 13th Brigade should attack

and clear the Etinehem spur at 10 p.m., at which hour,

too, the 10th Brigade (3rd Division) would advance south

of the Somme. The 10th Brigade, whose attack was

of necessity hurriedly conceived, met with considerable

opposition, and did not secure its objective until the

morning of the 12th.

To the troops of the 13th Brigade, waiting about

Chipilly and Cerisy, extra ammunition and bombs and

a good meal had set everything in order in the early

evening of August 10th. The whole brigade moved to

the northern bank of the Somme, undiscovered by Fritz's

"sausage" balloons, which, in the time our aeroplanes

allowed them up, had their work cut out to note the vast

movements everywhere on our side of the line. The

battalions, each a long worm of platoons, threaded their

way to Chipilly, and, hugging the steep sides of the re-entrants

to the north of it, pressed forward to the

assembly points in the Bois de Tailles, or, rather, in that

southern part of it known as Gressaire Wood. As they

passed our own howitzer batteries in action, cheery chaff

with the gunners kept their bright spirits buoyant. Ration

parties of Americans, patrols of Londoners, and one

little batch of mopped-up prisoners were passed en route,

and "good luck" from everywhere helped the way along.

All three battalions of the brigade took part in the

operation: The 49th (Queensland) was to drive for about

a mile along the Corbie-Bray road, close to the outskirts

of Bray, facing north towards the main strength of the

enemy on the Morlancourt heights, and east towards Bray

on its right; the 50th (South Australia) would work along

the Etinehem spur towards the river, while a company

of the 51st (West Australia) secured the exits of Etinehem,

and mopped-up the village at dawn next day.

Except that the 50th Battalion did not get so far this

night as was intended, thus giving the German a chance

to dig in along the southern parts of the spur, the objectives

of the brigade were duly reached. The attack was

made without a covering barrage, the artillery merely

engaging in some harassing fire and counter-battery work.

Four tanks, however, assisted on the left. The Germans

(Continued on Page 45)

Von Luckner (From Page 19)

prison-commandant's launch, in which they reached Red

Mercury Island and there lay in wait, until after a

couple of days two small schooners sailed by. One of

these they boarded and seized, and sailed in it to the

Kermadecs to obtain food; but there they were overtaken

and brought back by the cable-ship Iris, which during

the war carried arms. For the remainder of the war,

von Luckner was interned in Australia.

28 REVEILLE August 1, 1937

War Pension Talks

(By the Pensions Officer of the N.S.W. Branch of the

R.S.S.I.L.A. as a broadcast address from station 2BL)

In N.S.W. there are three principal schemes providing

special educational and training facilities for the children

of ex-soldiers:

(1) The Soldiers' Children Education Scheme, administered by the

Soldiers' Children Education Board, N.S.W., under the Repatriation Act.

(2) The Sir Samuel McCaughey Bequest, administered by the Trustees

of the A.I.F. Canteens Fund Trust, Victoria Barracks, Melbourne.

(3) War Bursaries, administered by the Bursary Endowment Board,

Department of Education, Bridge Street, Sydney.

Under the Repatriation Soldiers' Children Education

Scheme an eligible child means:-

(a) A son or daughter (including an ex-nuptial child) of a deceased

Australian soldier;

(b) A son or daughter (including an ex-nuptial child) of a totally

and permanently incapacitated soldier, born to the soldier not later

than 1/10/1931;

(c) A step-son, step-daughter, adopted son or adopted daughter of

a deceased or totally and permanently incapacitated soldier, provided

that the child was dependent upon the soldier prior to 1/7/1931.

"Deceased soldier" means a person whose death has

been accepted as due to war service, or who died from

any cause whatsoever, and was so seriously disabled

that immediately prior to his death he was pensioned

under Section 39A of the Repatriation Act.

"Totally and Permanently Incapacitated Soldier"

means a soldier who has been accepted by the Repatriation

Commission as incapacitated for life as a result of

war service, to such an extent as to preclude him from

earning other than a negligible percentage of a living

wage, or who has been classed as totally and permanently

incapacitated by an Assessment Appeal Tribunal, which

decides that its decision shall be binding for at least

three years.

"Australian Soldier" is defined as a member of the

Australian Naval and Military Forces appointed or enlisted

for service overseas, or a member of any of the

like Forces of the British Empire, provided that in the

latter case the soldier was permanently domiciled in Australia

at the time of his enlistment.

The minimum age at which a child may be granted

financial assistance under this scheme is thirteen years.

The assistance usually takes the form of an education

maintenance allowance.

In addition, the Education Board may, in special cases,

grant assistance for fees, text books and fares.

The education allowance is not in the nature of war

pension, and payment is contingent on the child undergoing

a course of training selected and approved by the

Education Board, and to the child making satisfactory

progress.

In actual fact, the allowance is paid so as to assist

the Board in preventing the child of a deceased or totally

and permanently incapacitated soldier from entering a

"blind alley" or an unskilled occupation.

Throughout the Commonwealth, over 16,000 children

have already been admitted to the benefits of the Soldiers'

Children Education Scheme. Of this number, nearly

10,000 have satisfactorily completed training for professions

and skilled occupations.

Application and all correspondence relative to assistance

under the provisions of the Education Scheme

should be addressed to the Deputy Commissioner, Department

of Repatriation, Box 3994, V.V., G.P.O., Sydney.

Those eligible under the terms of the Sir Samuel McCaughey

Bequest are the children of members of the

Australian Naval and Military Forces, who actually

served abroad during the Great War, and

(1) who died directly or indirectly as a result of War Service; and

(2) who have been certified as totally and permanently incapacitated

under the Repatriation Act.

With regard to par. 1, the trustees in some instances

admit children to the benefits of the bequest, who are not

entitled to receive assistance under the Soldiers' Children

Education Scheme, in consequence of the death of the

father not having been accepted as due to war service,

and of the children not coming within the provisions of

the Section 39A of the Repatriation Act. The trustees,

however, will not consider these applications until the

widow or guardian of the child has exercised her rights

of appeal under the Act.

The assistance granted by the trustees of the bequest

in the majority of cases takes the form of supplementary

grants for text books, fares, etc., to many of the children

receiving maintenance allowance under the Repatriation

Education Scheme. Where a child is being

granted benefits by the bequest, but is not eligible for

assistance under the Repatriation Education Scheme, the

assistance granted by the trustees includes a maintenance

allowance which is usually paid according to the scale

applicable to beneficiaries under the departmental scheme.

Application forms for assistance from the funds of the

Sir Samuel McCaughey Bequest may be obtained from

the office of the Trustees at Victoria Barracks, Melbourne,

or from the Deputy Commissioner, Department

of Repatriation, Sydney. (The Education Board, N.S.W.,

acts as the advisory body to the Trustees of the Bequest,

in so far as applicants residing in this state are concerned.)

The Bursary Endowment Board of the Department of

Education, awards bursaries to the children of deceased

soldiers where the death has been accepted as attributable

to war service, when such children are between the

ages of eleven and thirteen years. They also grant similar

bursaries to the children of seriously disabled soldiers.

No definite ruling appears to have been made by

the Bursary Endowment Board as to the definition of a

"seriously disabled soldier," but each case is considered

on its merits.

In addition, the Bursary Endowment Board will not

grant a Bursary to a child whose parents' income is in

excess of that laid down in the Bursary Endowment Act

of New South Wales.

Application forms for these bursaries may be obtained

from the Chairman of the Bursary Endowment Board,

Department of Education, Bridge Street, Sydney, or the

Deputy Commissioner, Department of Repatriation, Box

3994, VV, G.P.O., Sydney.

(Sub-branches or individuals who desire information "over the air"

on any problem or Repatriation, are invited to send in their questions

to the pensions officer, R.S.L. Headquarters, Anzac Memorial, Sydney,

and the answers will be given by the pensions officer in one of his

radio talks.)

LEFT LEG LOSSES

LIMBLESS SOLDIERS ASSOCIATION NSW

War's Toll

Many more left legs were lost during the great war than

right legs. In a check up on these statistics from the Canadian

Dept. of Pensions, as far as Australia is concerned, it is found

that on the books of the Repatriation Dept., there are approximately

2070 Diggers of whom 693 suffered amputation of the left

leg above the knee, and 409 of the left leg below the knee; while

631 suffered amputation of the right leg above the knee, and

338 of the right leg below the knee.

The cause of more left legs than rights being lost, one opinion

ventures, is that the left leg is forward when the soldier fires

his rifle.

Of the 1800 artificial eyes worn by Canadian war pensioners,

the same authority states, replacement is made every three or

four months. Color, too, has to be changed, as eyes change

color as a person grows older.

Wounds from bayonets must have been rare, for out of the

many thousands of war disabilities, investigated by the N.S.W.

pensions officer of the League, in furtherance of pension claims,

he has not yet come across a soldier who had suffered a bayonet

wound.

August 1, 1937 REVEILLE 45

Etinehem-Corbie Fight (From Page 27)

were completely taken aback, for an attack by tanks at

night was not the usual procedure, and how far it was

to go, they could not divine. So their artillery was silent,

the German S.O.S. going unanswered. Perhaps the

gunners were getting ready for a dash for home!

The tanks, which came along the Corbie-Bray road, met

the infantry at the point of assembly, and the co-operation

between the two was arranged in a five-minute conference

in a nearby dug-out. On the left of the attack

the Queenslanders, shaking out from their long "worm,"

deployed to open formation, with the Corbie-Bray road as

a guide on their left. One company moved ahead as

screen. The extreme left was protected by the tanks,

which went out one after another, their left-side guns

popping-off; as they ambled along at the end of their

"promenade," they turned about, and on the homeward

track gave their right-side guns a chance to inflict some

damage.

The Germans hardly used their machine-guns, except in

the sunken Etinehem-Bray road, about halfway to the

objective, and even here they soon either scuttled or surrendered.

The main difficulty of the attackers was to

know when they had gone far enough. The manoeuvre,

however, was simple enough, each company going forward

to its position in the point or side of the thrust. The

outskirts of Bray soon appeared before the advanced company,

and consolidation of the captured position was

begun.

On the right of the 49th's front was a deep ravine, of

which there are many about the banks of the Somme in

these parts. A small party of Germans sheltering here

made a small but gallant attack on the Australian line

near the head of this ravine, but was forced to retire, less

a machine-gun, an officer (wounded), and two others.

One episode during the advance is worthy of special

mention. A German machine-gun post located the

advancing sections, but a ground scout, who had become

separated from his companions, got on to it unnoticed by

the crew. Throwing in a bomb, he followed up with the

bayonet. One Boche was killed and another six surrendered

to him. On the line coming up he left with

these prisoners for the rear, but on the way got lost with

them. On his ordering them to show him the right direction,

one German led the wrong way, and was shot for

his pains. The lad, turning about, brought the rest in

safely. The Military Medal came his way later.

Another incident which occurred will serve to illustrate

the fear of the Australians that was held by many Germans,

and also their idea of our honour and methods. During

consolidation, three Germans, mere lads, were taken from

the shelter of drainage pits alongside the road. It was

arranged that they should be escorted back by a runner, as

soon as our position had been determined. They seemed

content enough until one of them, on being interrogated

some time later, discovered that they were in the hands

of Australians. He called to the others, and at once all

three began "kamerad-ing" for mercy, much to the amusement

of their escort. One of these same Fritzes, on being

kept waiting at battalion headquarters, asked whether he

was to be killed or not!

On August 11, our new positions, which were very

exposed, were heavily shelled. During the morning our

machine-guns, pushed well forward, inflicted some damage

on an enemy force moving against the 3rd Division on

the other side of the river, after which our positions came

in for some extra shelling. In the afternoon and evening

another force, estimated at two battalions, came in artillery

formation down the hills round Bray, evidently for a

counter-attack, which, however, did not develop, the artillery-

fire directed against it evidently being successful.

From a vantage point at the head of the ravine, the Lewis

gunners of the 49th Battalion made good shooting against

enemy messengers and carriers passing its mouth. One

gun here, working in conjunction with another belonging

to the 50th Battalion, accounted for no less than 17

Germans during the day.

During the heavy bombardment of our lines a German

post was established on the Corbie-Bray road, at which

a party of our walking wounded was later captured. An

attempt at their rescue resulted in our losing several men

killed and wounded, but the enemy post was dislodged.

Throughout August 11 the Germans did not play the

game. From points of advantage they fired with

machine-guns upon our stretcher-bearers, allowing no

movement whatever for the succour of the wounded. The

advanced company of the 49th had its four bearers shot;

these were replaced by volunteers, all of whom were likewise

hit during the day.

To meet the threat of the Germans who had dug in

at the southern end of the Etinehem spur, the 51st Battalion,

in brigade reserve in Gressaire Wood, sent forward

a second company to link the company about Etinehem

with the right of the 50th Battalion. At the same time

a company of Americans was moved from the wood into

closer support of our advanced positions.

The pocket of the river was finally cleared by continuing

the operation at 1 a.m. on August 13, when the remaining

two companies of the 51st, being all that was left

in brigade reserve, captured (at a cost of only five

wounded) 1 officer and 170 others, as well as 16 machine-

guns and trench mortars. Throughout this period the

American regiment was still handy in the wood, but what

with fighting and gas-shelling, it had undergone a trying

experience during the past few days, and, as a result, its

inexperienced troops were not in the best of condition.

However, when the pocket of the river was cleared the

brigade front was greatly shortened, and both the 50th

and 51st Battalions came back into brigade reserve.

This operation was carried out under the G.O.C. of the

4th Division, Major-General E. G. Sinclair-MacLagan. On

the evening of August 12, however, the Americans and the

13th Australian Brigade were formed into an independent

"Liaison Force," under Brigadier-General E. A. Wisdom.

On the night of August 11 and on succeeding nights,

the roads behind the German lines resounded with the

clatter of transport and caterpillars. For as far as the

eye could see the countryside was ablaze. All that the

enemy could save, was saved, for he knew that Bray

was doomed to fall almost at once. The platoon "Tacticians"

immediately set to work on new plans for preventing

his evacuation of the place.

REVEILLE August 1, 1937 46

With the Connaught

Rangers in Messpot.

(By Capt. Tom Kelsey, M.C., D.C.M.)

(Commenced in April Issue).

Photograph - see original document

The alarm had now been given, and it was no use trying

to surprise the Turks, so we dug in where we were and

waited until dawn. Then we discovered that Captain

Tommy Hewett, suspecting that we had lost direction, had

done a bit on his own. He had somehow collected about

250 men of the Punjabis, Ghurkas and Rangers, and captured

part of the Turkish line near the Twin Pimples. We

breathed freely once more, and went across, a platoon at

a time, to occupy and consolidate the line which Hewett

had captured.

We were relieved that night—April 16—and marched

across to the left of the Turkish position, where we dug

in, in depth, on a frontage of less than a hundred yards.

We were on the extreme right of the line, on the river,

with the 27th Punjabis on our immediate left, and the

remainder of the attacking force beyond the Punjabis.

This time General Egerton insisted on having an artillery

barrage, although the troops didn't want it. However,

at dawn on the 17th, the gunners laid a barrage on the

Turkish front line.

Our orders were to wait until the barrage lifted, but we

began to move forward beforehand. Now, there were no

orders given when the forward move started; the whole

line seemed to get the idea at the same instant, and we

all raced for the Turkish line, right into our own barrage.

Of the Rangers, Lieut. Beckett, at the head of 64 bombers,

led the attack. He was to bomb his way along to his

right, where the river curved. However, Beckett was hit

on the parapet, right in the shoulder. As I jumped over

him into the trench I head him yell, "Give the beggars

hell, Kelsey!"

I dropped into the trench beside Durrant. He was on

his back, a piece of shell through his foot, cursing everything

and everybody impartially. I got a crowd moving

to the right, behind the bombers, with C.S.M. Whelan in

charge, and Hewett yelled, "Let's get forward, Kelsey!"

I climbed out beside him, with Lieut. Lett, of my company

("A") on my left, and we raced for the next line, with

a crowd of Rangers behind us, reloading as we ran.

Then the barrage lifted to the next line, and we went

right into it. The second line, which appeared to be

the main Beit Aressa position, was constructed from a

deep irrigation channel leading from the river. There

was a trench, a six-foot high loop-holed bank behind it,

with a deep ditch (the irrigation channel) behind the

bank. Actually, it was a position with two tiers of

trenches.

Hewett, Lett and I reached the trench, took it in our

stride, and scrambled up the bank, and jumped—right

into the Turkish transport animals, which had apparently

just brought up the rations. I saw a Turk who looked

about ten feet high, with a poised bayonet at the end

of a rifle. Somehow or other, I twisted in the air, landed

on my elbows and knees as the bayonet came forward,

jerked up the muzzle of my revolver, and pulled the

trigger.

Then I fired under the bodies of the mules. I could

hear Lett cursing and shouting on my left, and Hewett

was busy on my right. I climbed to my feet and grabbed

a pony. Hewett grabbed it at the same time. "My pony,"

I gasped. "You be damned!" said Hewett, "I've just

plugged the owner! We'll share him!" Then the troops

surged over, and Hewett grabbed the leading man. "Take

this pony back and hand him over to the transport officer.

He's mine!" It was all over in a few seconds, and we

raced forward again, partly to keep the Turk on the

move, but mainly to get clear of our own barrage.

When the barrage died down we threw out outposts

and consolidated our captured positions, feeling rather

pleased with ourselves. The whole affair was over by

7 a.m., and we had time to remember little things we had

noticed during the "hurroosh". The native troops behaved

remarkably well that morning, and seemed to actually

enjoy it. I remember seeing a very tall corporal of the

Punjabis walking slowly through our own barrage, holding

a red casualty screen above his head at arm's length,

trying to let the gunners know where we were. Half-a-dozen

of his comrades formed a compact little group

round him, ready to defend him from the Turk.

The transport animals we had bumped into were still

loaded with rations, which our own troops collared. The

pony which Hewett had sent back was still with the

battalion when I joined the Dunsterforce, nearly two years

later. It was a beautiful little animal, with a remarkable

turn of speed. Hewett christened it "Billy the

Buddoo," and afterwards won several races on it.

When we had sorted ourselves out and sent back the

prisoners, we took things easy for a couple of hours. The

bombing sergeant reported to me in the advanced position

with 21 bombers. He said he thought I was the best man

to report to, and, anyway, he had to report to somebody.

Then my skipper (Captain Beard) sent two platoons to

the advanced position, and recalled my platoon to the

nullah. The bombers trailed along with me, but I sent

them to the adjutant. Battalion headquarters were in the

nullah, and the bombers might be useful as orderlies.

The Turk didn't let us get away with it. He counterattacked,

and drove in our outposts. But the main position

was too strong for a frontal attack to be successful,

and although the Turk launched several, they were beaten

off with severe loss. Unfortunately, our left flank was

absolutely in the air, and the Turk eventually occupied

the nullah on the extreme left of our line, and worked

down. The battalion on the extreme left, finding its

flank turned, dropped back to the next line, the original

Turkish front trench, and hung on there. Each battalion

[*Reveille

Nov. 1937*]

MONASH'S GENIUS.

General Herring's

Tribute

Etinehem Spur Capture.

Photograph - see original document

General Herring

I read with interest in the August number of "Reveille"

Captain Tambling's account of the Etinehem and Corbie-Bray

Road operations. In my opinion, this minor operation

was one of the sidelights on the great military genius

of General Monash and of his great thoroughness and

attention to detail.

As Captain Tambling relates, the situation on August

10 was that although great progress had been made on

the south side of the Somme, the advance on the north

side had been more or less held up. Consequently the

Australian Corps, which was attacking on the south side

could not safely advance much further until their left

flank was secure.

Quick to act, General Monash decided that Etinehem

Spur must be taken without delay. Ascertaining that

the 13th Brigade was available, and knowing the delay

that must occur if his orders had to go through the

usual corps and divisional routine, he immediately got

in touch with the 4th Divisional Commander and asked

that the 13th Brigade be made available for a special

operation, and advised him that he would see

the brigade commander at divisional headquarters at 11

a.m. and give him his instructions verbally.

On arrival at divisional headquarters (I was commanding

the 13th Brigade at the time) I found General Monash

already there and studying a map. Explaining the situation

to me, he said, "I want you to move your brigade

across the Somme and take the Spur. When can you do

it?" I explained that by the time I had received my

orders and got my troops ready to move it would be too

late to do it that night, but that I could do it the following

night.

"That is no good, Herring," he replied. "It must be

done to-night for two reasons. First, I cannot continue

my advance until my left flank is secure; and, second,

the Germans holding the Spur have already been attacked

twice, and are sure to be in a more or less disorganised

state; but give them twenty-four hours to consolidate and

it might not be possible for you to take the Spur. I can,

however, save you a lot of time, as I will personally see

that you C.O.'s, etc., are not only advised to be at your

H.Q. at 1 p.m., but also to have their troops ready to move

by 4 p.m." I, of course, saw the force of his argument,

and agreed to attack that night.

He then gave the necessary instructions to be telephoned,

and said, "Now, tell me how you propose to attack."

I briefly outlined my ideas, and he agreed as to

the general principles, and then told me he would place

at least four tanks at my disposal, and advised me as to

how he thought they should be used. He then advised

me as to how to make the best use of my artillery, and

we also discussed the various phases of the infantry

attack. He closed the conference by saying, "The best

of luck, Herring. Get back to your H.Q. as quickly as

you can; and I am sure by this time to-morrow you will

find you are in possession of Etinehem Spur."

On arrival at my H.Q. I found my C.O.'s, the artillery,

and tank commanders, etc., waiting for me. I explained

the situation to them, and gave out my various orders,

and by 4 p.m. the 13th Brigade had started on their move

across the Somme. Shortly after daylight next morning,

I was able to ring up division headquarters and report

that I had captured my objective and was consolidating.

General Monash must have devoted at least three to

four hours of his time to this minor operation, but as a

result his left flank was strongly held, and the next day

his corps continued their victorious push through the

German line.

I hope you will find the foregoing of sufficient interest

to publish in "Reveille." I am having a very extended

holiday over in this part of the world, but hope to be back

in Sydney early next year.

SYDNEY C. E. HERRING, Brig.-General, London. Oct. 3

Deb Parkinson

Deb ParkinsonThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.