Charles E W Bean, Diaries, AWM38 3DRL 606/253/1 - 1918 - 1939 - Part 15

AUSTRALIA'S GREATEST WAR TROPHY

It is probably not generally known that the finest trophy captured

by any nation participating in the Great War is the 11 inch high velocity railway

gun taken from the Germans by the Australians near Harbounnieres on 8th August 1918.

This magnificent weapon was greatly coveted as a war trophy by the French, who

claimed it by reason of the fact that it was captured on French soil, and for the

further reason that it had done very material damage to Albert, Amiens, and other

towns in the forward areas.

The Royal Air Force also put in a claim owing to the part played by

British airmen in bombing the railway track on which it was running and the

ammunition trucks attached, thus more or less immobilizing the gun and mounting.

British cavalry, though they passed through considerably after the

Australian infantry, considered they had a right to it.

The R. E. thought they should be credited with the capture as some

Engineers attached to the 31st Battalion A.I.F. had repaired the damaged railway

track, had raised steam on the towing engine, and had drawn the gun and mounting

out of enemy range to a position within our lines.

It was subsequently decided after much discussion that the 31st

Battalion should be awarded the trophy, the C.O. (Lt.-Col. Neil Freeman) having

conclusively proved that the gun while still firing had come under the machine gun

and rifle fire of his unit and kept under fire after the Battalion had passed through.

Attempts were made by interested parties to bring back to Australia,

in preference to the 11 inch gun, another gun, viz the 15 inch German weapon

from Arcy Wood, near Chuignes. It was wisely decided however, that while the

11 inch weapon itself was smaller than the 15 inch gun, the railway gun with its

mounting was in actual fact a larger trophy and was moreover a genuine capture,

made while it was still firing during the Australian attack. The 15 inch gun on

the other hand had been blown up by the Germans themselves two days prior to our

attack and took no part in the battle itself. (This gun and mounting were formally

presented to the people of Amiens by Gen. Sir Wm. Birdwood). The weapon and

mounting had been rendered quite useless the breech end being completely shattered

and strewn in all directions and the gun thrown out of its mounting, which was of

the circular turn-table fixed type.

Furthermore, the broad-gauge railway line by means of which ammunition

and supplies had been brought up to the gun had been pulled up for about three

quarters of a mile.

To restore this line to permit the damaged gun only being moved to the

-2-

main line would have entailed much labour and expense; apart from material more

urgently required elsewhere.

The railway gun on the other hand was capable of being moved by its own power

and on its own mounting on the existing railway line to the coast.

Another factor influencing the decision was that about this time the

Americans and other Nations were favouring the railway type of gun for coast defence;

and it was considered that this weapon would be of interest to artillery students

in Australia.

The British Army in France towards the end of the War had several 14 inch

railway guns and also an 18 inch weapon on railway mounting.

After capture the trophy was removed to Paris and exhibited in the Champs

de Mars where it attracted much attention.

It had been in the first instance inscribed "Captured by the 31st

Battalion A.I.F." but this was altered to "Captured by the British IVth Army",

which inscription it bore until its arrival in Australia.

In October 1918 it was moved to Calais and thence in February 1919 by

train ferry across the Channel to Richborough the famous "Hush" port and base near

Deal in England.

From Richborough it was subsequently moved to Woolwich for detailed

examination and test by British naval and military experts and finally to Chatham

Dockyard.

Owing to the top loading gauge being too great with the gun mounted on

its carriage to pass under the tunnels of the S.E. and Chatham railway it was

arranged for the gun to travel separately from the mounting to Woolwich. The

Woolwich tests being completed arrangements were made to transport the prize to

Australia by one of several vessels of the Commonwealth line. Amongst these

were the Gilgai, Araluen, etc.

On several occasions after full preparations had been made to ship the

gun, at the last moment arrangements were cancelled and it looked as though the

trophy would never reach Australia.

The masters of several vessels made no secret of the fact that it was a risky

job to stow such a bulky, awkward and weighty cargo in any ship likely to encounter

rough seas.

Eventually, however, Capt. Waldron, a wellknown sea captain who in pre-war

days had commanded the S.S. "Ferret" between Albany and Esperance, W.A. and

at this time captain of S.S. "Dongarra" was approached. He readily assented and

stated that he regarded the task as a great privilege.

-3-

Admiral Goodenough, son of a wellknown naval officer who took a prominent part

in the survey of the Australian coast in the early days, was at this period Admiral

Superintendent at Chatham.

He also entered most enthusiastically into the scheme and made all

arrangements to load the trophy into the "Dongarra" at Chatham Dockyard, provided

the Woolwich Arsenal authorities placed it under the big crane at The Basin. He

had the Basin cleared of all shipping to facilitate the movement of the "Dongarra"

and permit of loading being effected at flood tide.

A model in wood had been made of the undercarriage and of the hatch of

the "Dongarra" to test whether this huge structure would dip correctly into the

hatch; and in due course the whole of the parts of the actual trophy totalling

185 tons were safely loaded without mishap. In London two important factors had

to be considered prior to finalizing arrangements; firstly the question of railway

gauge at the port of disembarkation and secondly the availability of a suitable

crane to take the huge weights from ship to rail.

It was obvious that the port of disembarkation must be in N.S.W.

The General Manager of the Broken Hill Proprietary (Mr. Delprat) happened

to be in London at the time and offered to place all the Company's facilities and

skilled personnel at Newcastle at our disposal.

Mr. Shellshear, Consulting Engineer of the N.S.W. Railways in London, gave

valuable advice on the matter of axle loads on the Hawkesbury Bridge. The axle

load of the whole trophy complete was 18 tons, which would have exceeded the safe

load for the bridge.

With the gun removed the axle load was 11 tons only and it was therefore

arranged for the gun to travel on two flat trucks as a separate unit. Just at

this time however, information was received in London that the naval floating

crane "Titan" was available in Sydney and was capable of handling weights up

to 200 tons. This solved the problem and a cable was despatched to Cockatoo

Dock, Sydney, asking for the bogeys, central pivot, undercarriage and gun to be

unloaded from the "Dongarra" in Sydney direct on to the rails. This was done

at Jones Bay, Darling Harbour, but as three (3) reserve guns of H.M.A.S. Australia

had been loaded into the "Dongarra" on top of the German gun these were first

unloaded by the "Titan" at Garden Island.

The N.S.W. railway workshops at Everleigh with the assistance of

Lt. Pockett, A.A.O.C. assembled all fittings and parts.

The Premier (Mr. Holman) had been asked from London to have an existing

railway track at Central Station extended to Eddy Avenue and to have a ramp

-4-

constructed for the trophy to rest on. This the Premier agreed to do and when the

parts had been assembled at the Workshops the complete trophy was pushed down by

an engine onto the ramp. Owing to the great weight the lines sank slightly

immediately under the two bogeys and the gun and mounting were drawn back by

engine to allow two plates to be inserted under the lines to strengthen them.

When pushing the trophy back to its new strengthened bed the brakes failed to act

and one bogey ran over the end of the ramp, portion of the undercarriage being in

mid-air for some days. By the use of powerful jacks railway engineers skilfully

replaced the trophy in its correct position.

Arrangements were made with the Australian General Electric Coy. to

flood-light the trophy by night for some weeks prior to and during the visit of

H.R.H. The Prince of Wales who inspected and greatly admired it. Thousands of

people passing by day and night viewed the trophy until it was eventually moved

to its present and final resting place at Canberra where it will remain as a

magnificent monument to the 31st Battalion A.I.F., to the victory of the 8th

August and to the work of the whole of the A.I.F.

The following facts in connection with the trophy may be of interest:--

Weight of gun (only) - 45 tons.

Length of gun (only) - 36 ft. 9 inches.

Greatest diameter - - 45.5 inches.

Diameter of bore (at muggle) - 11.2 inches.

Maximum range - 26,000 yards.

Undercarriage - 80 tons.

Bogeys (2) - - each 15 tons.

Central pivot - 10 tons.

Total weight of gun, mounting, parts, fittings etc. - 185 tons.

Length of carriage - 72 ft. (overall).

Length of carriage - 55 ft. (stripped).

Width of carriage - 8 ft. 8 in.

Width of carriage (stripped) - 6 ft. 6 in.

Height of gun above rails - 13 ft. 8 in.

28 c.m. (11.2 inch) Naval Shell.

Shell complete - 665.8 lbs.

GE Manchester

Lt Col

Australian Staff Corps

REVEILLE

July 1, 1934.

GREATEST WAR TROPHY

31st Battalion's Capture in France

Diagram, Broadsheet, or printed page - see original document.

How the monster 11-inch railway gun, which was captured by the 31st

Bn., A.I.F., at Harbonnieres on the opening day of the August, 1918,

offensive, was transported to Australia - how all difficulties, some political,

were overcome, including the designs of the French to retain it as a trophy

of war for their people - is told in this article by Lieut.-Col. G. E.

Manchester, of the Australian Staff Corps, who had charge of all the

arrangements.

THE finest trophy captured by any nation participating

in the Great War is the 11-inch high velocity railway

gun taken from the Germans by the Australians

near Harbonnieres on August 8, 1918. This magnificent

weapon was greatly coveted as a war trophy by

the French, who claimed it by reason of the fact that it

was captured on French soil, and for the further reason

that it had done very material damage to Albert, Amiens,

and other towns in the forward areas.

The Royal Air Force also put in a claim, owing to

the part played by British airmen in bombing the railway

track on which it was operated and the ammunition

trucks attached, thus more or less immobilising the

gun and mounting. British cavalry, though they passed

through considerably after the Australian infantry, considered

they had a right to it. The R.E. thought they

should be credited with the capture, as some engineers

attached to the 31st Bn., A.I.F., had repaired the damaged

railway track, had raised steam on the towing

engine, and had drawn the gun and mounting out of

enemy range to a position within our lines.

After much discussion the 31st Bn. was awarded the

trophy, the C.O. (Lieut.-Colonel Neil Freeman) having

conclusively proved that the gun, while still firing, had

come under machine-gun and rifle fire of his unit and

been kept under fire after the battalion had passed through

Attempts were made by interested parties to bring back

to Australia, in preference to the 11-inch gun, another

gun, viz., the 15-inch German weapon from Arcy Wood,

near Chuignes. It was wisely decided, however, that

while the 11-inch weapon itself was smaller than the

15-inch gun, the railway gun, with its mounting, was

in actual fact a larger trophy, and was moreover a

genuine capture, made while it was still firing during

the Australian attack. The 15-inch gun, on the other

hand, had been blown up by the Germans themselves two

days prior to our attack, and in the end this gun and

mounting were formally presented to the people of Amiens

by General Sir Wm. Birdwood.

A factor influencing the decision to have the railway

gun captured at Harbonnieres sent to Australia was that

about this time nations, including America, were favouring

the railway type of gun for coast defence, and

it was considered that this weapon would be of interest

to artillery students in Australia. The British Army in

France towards the end of the war had several 14-inch

railway guns, and also an 18-inch weapon on railway

mounting.

After capture the trophy was removed to Paris and

exhibited in the Champs de Mars, where it attracted

much attention. It had been in the first instance inscribed,

"Captured by the 31st Bn., A.I.F.," but this was

altered to, "Captured by the British IV. Army," which

inscription it bore until its arrival in Australia. In

October, 1918, it was moved to Calais, and thence, in

February, 1919, by train ferry across the Channel to

Richborough, the famous "Hush" port and base near

Deal in England. From Richborough it was subsequently

moved to Woolwich for detailed examination and test by

British naval and military experts, and finally to Chatham

Dockyard.

Owing to the top loading gauge being too great with

the gun mounted on its carriage to pass under the tunnels

of the S.E. and Chatham railway it was arranged

for the gun to travel separately from the mounting to

Woolwich. The Woolwich tests being completed, arrangements

were made to transport the prize to Australia. On

several occasions, after full preparations had been made

to ship the gun, at the last moment arrangements were

cancelled, and it looked as though the trophy would never

reach Australia. The masters of the Commonwealth Line

vessels made no secret of the fact that it was a risky job

to stow such a bulky, awkward and weighty cargo in

any ship likely to encounter rough seas. Eventually,

however, Capt. Waldron, a well-known sea captain, who

in pre-war days had commanded the s.s. Ferret between

Albany and Esperance, W.A., and at this time was captain

of s.s. Dongarra, was approached. He readily

assented, stating that he regarded the task as a great

privilege.

Admiral Goodenough, son of a well-known naval

officer, who took a prominent part in the survey of the

Australian coast in the early days, was at this period

Admiral Superintendent at Chatham. He also entered

enthusiastically into the scheme, and made all arrangements

to load the trophy into the Dongarra at Chatham

Dockyard, and had the Basin cleared of all shipping to

facilitate the movement of the Dongarra and permit of

loading being effected at flood tide.

A model in wood had been made of the undercarriage

and of the hatch of the "Dongarra" to test whether this

huge structure would dip correctly into the hatch; and in

669.

of some of the Black Line commanders staffs and commanders, and a dangerous degree of

inaccuracy in the barrage were responsible - the whole of the

final objective between the Blauwepoortbeek valley and the Douve

had by 9 p.m. been left open to the enemy.

(8-point)

German narratives imply that the whole

of the line thus left empty was reoccupied

by German troops, but this is almost

certainly wrong. The counter-attacking

German troops, whom the 47th had in part

repulsed, belonged to the 1st Guard

Reserve and 5th Bavarian R.I. Regiments,

which e had been coming up throughout the

afternoon. The 18th Bavarian I.R. was

relieved that night by the III/1st Guard

Reserve Regiments, which ^ which undoubtablly took over the Oosttaverne held the Line inthereafter the Blauwepoortbeek valley.

Space here → x x x x

As a result of the same ^ similar causes ^ to those that forced the retirement

near Huns' Walk, the northern section of/the II Anzac troops was

II Anzac - plunged into almost equal difficulties. Here the

thick black) Northern

front position had been strengthened since 5 p.m. After

[*indent 3 lines*]

the capture of Van Hove Farm Captain Maxwell had asked the two

unengaged tanks to move forward towards Joye Farm. While working

down the Wambeek valley both became ditched, but, as they were

(TAKE IN SKETCH No. 262 251)

in a position to serve as forts opposing any attack up the

valley, their crews stayed and manned them throughout the night.

Fragments of the 33rd Brigade, which came up and asked their way,

were directed by Maxwell to fill the gaps. While seeking for

such troops on his left flank, he obtained touch with some on

the Black Dotted Line of the IX Corps. Although these could not

come forward, they would ^ were a safeguard ^ to the left. 14

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

14 F1 The intelligence officer of the 33rd Brigade had told him ^ Maxwell that

there were troops back along the railway line in the Wambeek

valley. The 6th Border afterwards obtained touch here with the

12th Royal Irish Rifles holding the 36th Division's Black Dotted

Line. These were forbidden by their orders from reinforcing in

the Oosttaverne Line.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Since 5 p.m. the 13th Brigade's advanced line on the

Wambeek had been troubled by the short-shooting of a heavy

battery on its left and of eighteen-pounders on its right.

Several messages had been sent asking for range to be lengthened,

773

due course the whole of the parts of the actual trophy

totalling 185 tons were safely loaded without mishap

In London two important factors had to be considered

prior to finalising arrangements - firstly the question of

railway gauge at the port of disembarkation, and secondly

the availability of a suitable crane to take the huge

weights from ship to rail.

It was obvious that the port of disembarkation must

be in N.S.W. The general manager of the Broken Hill

Proprietary (Mr. Delprat) was in London at the time,

and offered to place all the company's facilities and skilled

personnel at Newcastle at our disposal. Mr. Shellshear,

consulting engineer of the N.S.W. Railways in London,

gave valuable advice on the matter of axle loads on

the Hawkesbury Bridge. The axle load of the whole

trophy complete was 18 tons, which would have exceeded

the safe load for the bridge.

With the gun removed the axle load was 11 tons only,

and it was therefore arranged for the gun to travel

on two flat trucks as a separate unit. Just at this time,

however, information was received in London that the

naval floating crane Titan was available in Sydney, and

was capable of handling weights up to 200 tons. This

solved the problem, and a cable was despatched to Cockatoo

Dock, Sydney, asking for the bogeys, central pivot,

undercarriage, and gun to be unloaded from the Dongarra

in Sydney direct on to the rails. This was done at

Jones Bay, Darling Harbour, but as three reserve guns

of H.M.A.S. Australia had been loaded into the Dongarra

on top of the German gun, these were first unloaded by

the Titan at Garden Island.

The N.S.W. Railway Workshops at Eveleigh, with the

assistance of LIeut. Pockett, A.A.O.C., assembled all fittings

and parts. The then Premier (Mr. Holman)

had been asked from London to have an existing railway

track at Central Station extended to Eddy Avenue, and

to have a ramp constructed for the trophy to rest on.

This he agreed to do, and when the parts had been

assembled at the workshops the complete trophy was

pushed down by a engine on to the ramp. Owing to

the great weight the lines sank slightly immediately under

the two bogeys, and the gun and mounting were drawn

back by the engine to allow two plates to be inserted under

the lines to strengthen them. When pushing the trophy

back to its new strengthened bed the brakes failed to

act, and one bogey ran over the end of the ramp, portion

of the undercarriage being in mid-air for some

days. By the use of powerful jacks, railway engineers

skilfully replaced the trophy in its correct position.

Arrangements were made with the Australian General

Electric Coy. to floodlight the trophy, and the Prince of

Wales, during his visit to Sydney, greatly admired it.

Thousands of people viewed the trophy, which was eventually

moved to its present and final resting place at Canberra,

where it will remain as a magnificent monument

to the victory of August 8, and to the work of the whole

of the A.I.F.

The following facts in connection with the trophy may be of interest :-

Weight of gun (only), 45 tons; length of gun (only), 36ft.

9in.; greatest diameter, 45.5in.; diameter of bore (at muzzle), 11.2in. ;

maximum range, 26,000 yards; undercarriage, 80 tons; bogeys (2),

each 15 tons; central pivot, 10 tons; total weight of gun, mounting,

parts, fittings, etc., 185 tons; length of carriage, 72ft. (overall); length

of carriage, 55ft. (stripped); width of carriage, 8ft. 8in.; width of

carriage (stripped), 6ft. 6n.; height of gun above rails. 13ft. 8in.;

28 c.m. (11.2in.) naval shell; shell complete, 665.8lb.

668A.

immediately brought back. Major Story, who had not wished the

barrage to be shortened, asked his brigadier (McNicoll) first,

that it should be lengthened to the afternoon's objective, and,

later, that it should be still further lengthened so that the

37th might go back to the advanced line.

Thus, owing to the action of its own artillery - for which

defects in the maps, over-eagerness of the infantry, over-anxiety

772

November, 1929. VICTORIAN POSTAL INSTITUTE MAGAZINE. 9

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ X

The Battle of Amiens

WITH THE FIFTEENTH BRIGADE ON 8th AUGUST,

1918,

By J. J. McKenna.

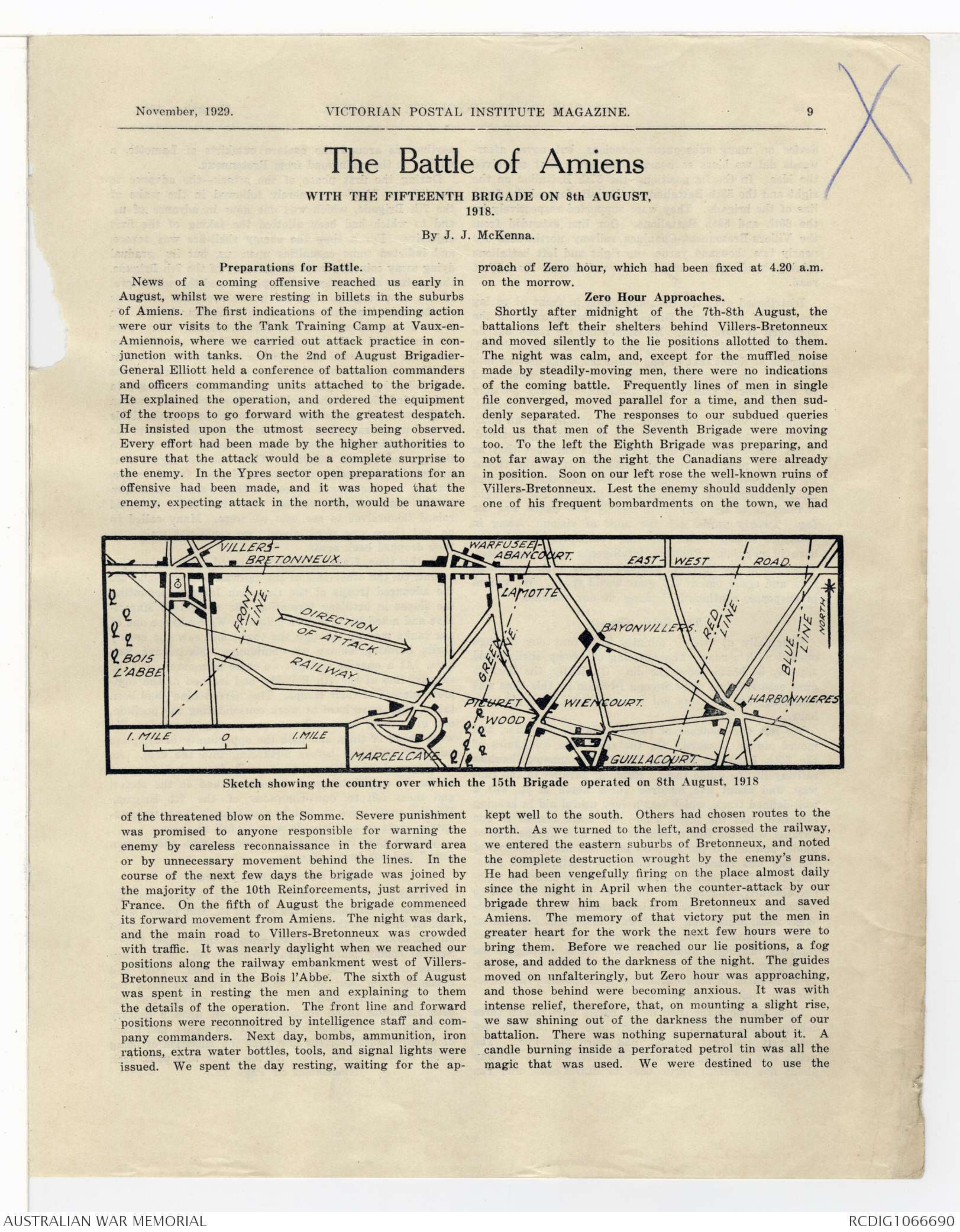

Preparations for Battle.

News of a coming offensive reached us early in

August, whilst we were resting in billets in the suburbs

of Amiens. The first indication of the impending action

were our visits to the Tank Training Camp at Vaux-en-Amiennois,

where we carried out attack practice in conjunction

with tanks. On the 2nd of August Brigadier-General

Elliott held a conference of battalion commanders

and officers commanding units attached to the brigade.

He explained the operation, and ordered the equipment

of the troops to go forward with the greatest despatch.

He insisted upon the utmost secrecy being observed.

Every effort had been made by the higher authorities to

ensure that the attack would be a complete surprise to

the enemy. In the Ypes sector open preparations for an

offensive had been made, and it was hoped that the

enemy, expecting attack in the north, would be unaware

Diagram, Broadsheet, or printed page - see original document.

Sketch showing the country over which the 15th Brigade

operated on 8th August, 1918

of the threatened blow on the Somme. Severe punishment

was promised to anyone responsible for warning the

enemy by careless reconnaissance in the forward area

or by unnecessary movement behind the lines. In the

course of the next few days the brigade was joined by

the majority of the 10th Reinforcements, just arrived in

France. On the fifth of August the brigade commenced

its forward movement from Amiens. The night was dark,

and the main road to Villers-Bretonneux was crowded

with traffic. It was nearly daylight when we reached our

positions along the railway embankment west of

Villers-Bretonneux and in the Bois l'Ábbe. The sixth of August

was spent in resting the men and explaining to them

the details of the operation. The front line and forward

positions were reconnoitred by intelligence staff and company

commanders. Next day, bombs, ammunition, iron

rations, extra water bottles, tools, and signal lights were

issued. We spent the day resting, waiting for the approach

of Zero hour, which had been fixed at 4.20 a.m.

on the morrow

Zero Hour Approaches.

Shortly after midnight of the 7th-8th August, the

battalions left their shelters behind Villers-Bretonneux

and moved silently to the lie positions allotted to them.

The night was calm, and, except for the muffled noise

made by steadily-moving men, there were no indications

of the coming battle. Frequently lines of men in single

file converged, moved parallel for a time, and then suddenly

separated. The responses to our subdued queries

told us that men of the Seventh Brigade were moving

too. To the left the Eighth Brigade was preparing, and

not far away on the right the Canadians were already

in position. Soon on our left rose the well-known ruins of

Villers-Bretonneux. Lest the enemy should suddenly open

one of his frequent bombardments on the town, we had

kept well to the south. Others had chosen routes to the

north. As we turned to the left, and crossed the railway,

we entered the eastern suburbs of Bretonneux, and noted

the complete destruction wrought by the enemy's guns.

He had been vengefully firing on the place almost daily

since the night in April when the counter-attack by our

brigade threw him back from Brettoneux and saved

Amiens. The memory of that victory put the men in

greater heart for the work the next few hours were to

bring them. Before we reached our lie positions, a fog

arose, and added to the darkness of the night. The guides

moved on unfalteringly, but Zero hour was approaching,

and those behind were becoming anxious. It was with

intense relief, therefore, that, on mounting a slight rise,

we saw shining out of the darkness the number of our

battalion. There was nothing supernatural about it. A

candle burning inside a perforated petrol tin was all the

magic that was used. We were destined to use the

10 VICTORIAN POSTAL INSTITUTE MAGAZINE. November, 1929.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

device on many subsequent occasions, but never afterwards

did we bless so heartily the brain that conceived

the idea. In the lie positions, the 57th Battalion on the

right and the 59th Battalion on the left, formed the front

line of the brigade. They were supported respectively by

the 60th and 58th Battalions. Our line extended from

the Villers-Bretonneux-Chaulnes railway northwards for

nearly two thousand yards, the right and left battalions

joining hands just south of the well-known East-West

road.

Distributed over the thousand yards in front of us lay

the men of the Second Division, confidently awaiting the

approach of Zero hour. No sooner did we reach our lie

position than the enemy opened a brisk bombardment.

There is no doubt that he had heard the ranks moving into

position. Also, the shouting of the tank personnel could

be heard for a considerable distance, and may possibly

have reached the ears of his sentries. The barrage,

though not violent, was heavy, and continued for an hour.

It showed no signs of abating as Zero hour approached.

What was even more disquieting was the fact that as

Zero drew near we were still doubtful if all the troops

were in position and ready. There was then sufficient

light to permit the recognition of comrades, but the light

enabled us to see only more clearly how dense was the

fog. Twenty yards was the limit of vision. Away in

front, enveloped in the fog, the companies should have

been in position. Runners, intelligence staff, signallers,

were out in the barrage, groping in the mist, searching.

Now and again one of our guns would speak. We waited

in suspense, continually looking at our watches.

The Battle Opens.

Punctually at twenty minutes past four our barrage

opened with a roar. The bursting of enemy shells could

scarcely be heard above the din. Gradually, the German

guns ceased firing. The Second Division by this time was

attacking, but we were not to move until Zero plus

one hour.

We left our trenches at twenty minutes past five, and

moved slowly forward. On the right, the companies of

the 57th Battalion had the Villers-Bretonneux-Chaulnes

railway line to guide them. Running parallel to the railway,

and about five hundred yards north of it, was a

well-defined track, which was a very useful aid in keeping

direction. At the point where the track ceased to run

parallel with the line a light railway took up the role of

guide, and served the purpose until the first objective of

the day was reached. By that time the daylight had penetrated

the fog, and it was possible to keep the direction without

difficulty. On the left the 59th Battalion was not so

fortunate. The only well-defined landmark was the East-

West road, which ran off at angle from the line of

advance. Direction was kept almost solely by the aid of

compass bearings, which, with admirable foresight, the

intelligence officer had notified to all platoon commanders.

In some cases in both battalions small parties lost direction,

but quickly regained it.

Upon all the maps used in the battle were drawn three

colored lines - green, red, and blue - to indicate respectively

the first, second, and third objectives. The

green line, marking the first objective cut the railway

about five hundred yards east of Marcelcave, and ran

northwards around the eastern outskirts of Lamotte, a

village on the main road from Bretonneux.

During the first phase of the attack—the advance to

the "Green Line"—we merely followed in the wake of

the 7th Brigade, which was one hour in advance of us,

and to which had been allotted the taking of the first

objective. For a time the enemy shell-fire was severe,

and inflicted some casualties upon us, but its gradual

dying away coincided with the advance of the 7th Brigade,

the capture of the enemy field-pieces, and the withdrawal

of the heavier guns. Around us we could see evidences

of the fight that had occurred only an hour before. In

front of the enemy trenches lay our dead. They were

not many, and had evidently been killed by machine-gun

fire. As we crossed the trenches we noted grimly that

all the enemy gunners had not escaped unhurt. Some

had fallen by their guns, but the equipment scattered in

and behind the trenches told of others who took sudden

dislike to steel as the bayonets came close. In the fields

around us we saw piecdes of white flag fluttering from the

butts of rifles which had been reversed and thrust into

the ground by the bayonet. This was the signal that

indicated the presence of a wounded man, friend or foe,

waiting for the stretcher-bearers that were to take him

to the rear. As we passed, those not badly wounded

raised themselves to see who we were. Many called to

us, but there was work ahead; we could not wait, and

they dropped back again.

By this time, 7 a.m., the fog had lifted to a considerable

extent. On the other side of the railway line we could see

the advanced troops of the Canadian Infantry mounting

the slopes in artillery formation. We recognised Marcelcave

and noted its shell-torn chimney. We could see one of

our tanks moving through the town, and saw the enemy

shells bursting among the buildings. Marcelcave was

ours. At a quarter to eight we came in contact with the

support line of the 7th Brigade, and learned of the complete

success of their troops. The "Green Line" had been

taken, they were hard at work consolidating the position,

and everything was ready for our passage onwards. We

were ahead of time, and took the opportunity to complete

our reorganisation before advancing into the void. As

it happened, the "Green Line" was drawn behind most

of the 77 centimetre guns the enemy had on the sector,

and these fell to our comrades of the 7th Brigade.

Heavier guns were to fall to our brigade, and, unfortunately,

some of our brigade were to fall to them.

At Zero plus four hours we were through the "Green Line",

and our turn had come.

Under Direct Artillery Fire.

Visibility was good; Bayonvillers was in sight, and we

could see our barrage playing around it. Our planes were

well on time with their smoke bombs. These they dropped

on the town shortly after we crossed the "Green Line".

Several enemy planes appeared, flying very low. They

passed over us, and flew well to our rear. They had

evidently been sent out to discover on what scale the

attack was being made. Close to the railway line the

57th Battalion found themselves almost upon a battery

of 5.9 guns. The gunners fired over the sights, and many

of us experienced for the first time the sensation of being

under direct artillery fire. As the shells tore past, each

(Continued on Page 12.)

Sam scott

Sam scottThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.