Charles E W Bean, Diaries, AWM38 3DRL 606/252/1 - 1918 - 1935 - Part 1

AWM38

Official History,

1914-18 War: Records of C E W Bean,

Official Historian.

Diaries and Notebooks

Item number: 3DR1606/252/1

Title: Folder, 1918- 1935

Comprises various papers on Hazebrouck,

including notes by Bean and A W Bazley, letters

by Lt Col W D Joynt VC, and extracts from the

diary of Pte HG Hartnett.

AWM38-3DRL606/252/1

HAZEBROUCK, 1918. No.252.

1st SET.

AWM 38 3DRL 606 ITEM 252 [1]

DIARIES AND NOTES OF C. E. W. BEAN

CONCERNING THE WAR OF 1914- 1918

THE use of these diaries and notes is subject to conditions laid down in the terms

of gift to the Australian War Memorial. But, apart from those terms, I wish the

following circumstances and considerations to be brought to the notice of every

reader and writer who may use them.

These writings represent only what at the moment of making them I believed to be

true. The diaries were jotted down almost daily with the object of recording what

was then in the writer’s mind. Often he wrote them when very tired and half asleep

also, not infrequently, what he believed to be true was not so —but it does not

follow that he always discovered this, or remembered to correct the mistakes when

discovered. Indeed, he could not always remember that he had written them.

These records should, therefore, be used with great caution, as relating only what

their author, at the time of writing, believed, Further, he cannot, of course, vouch

for the accuracy of statements made to him by others and here recorded. But he

did try to ensure such accuracy by consulting, as far as possible, those who had

seen or otherwise taken part in the events. The constant falsity of second-hand

evidence (on which a large proportion of war stories are founded) was impressed

upon him by the second or third day of the Gallipoli campaign, notwithstanding that

those who passed on such stories usually themselves believed them to be true. All

second-hand evidence herein should be read with this in mind.

C. E. W. BEAN.

16 Sept, 1946.

AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL

ACCESS STATUS

OPEN

The Times Literary Supplement

16/7/1925

LUDENDORFF UNVEILED.

LA BATAILLE DES FLANDRES D'APRÈS LE

JOURNAL DE MARCHE ET LES ARCHIVES DE

LA IVE WE ARMÉE ALLEMANDE (9-30 AVRIL.

1918). Documents secrets pris à l' ennemi.

Traduction. Publié sous la direction du

Service historique de l'Etat-Major de

l'Armée, Colonel RENÉ TOURNÈS et

Capitaine HENRY BERTHEMET. (Paris:

Charles-Lavauzelle, 20f.)

A French translation of a quantity of

captured German military documents-even

though they comprise the war diary and

archives of an army, and that army the

Fourth, engaged in what we call the Lys

offensive of 1918—did not seem to promise

anything except of technical and professional

interest, historically more of value to the

British than the French. But a study of them,

aided by the excellent introduction and

comments provided by two officers of the French

historical section of the General Staff, takes

us behind the scenes of the German Command

in a most unexpected way; for the capture

includes not only the ordinary papers that

might be anticipated but a variety of others,

and even the record of telephone conversations.

They reveal Ludendorff in quite a new

light, and fully confirm what certain German

writers have already disclosed: that the

German Army was run not by the generals

whose names were before the public but by

that strongest of all trade unions, the German

General Staff.

The war diary is much what one would

expect, fairly accurate but inclined, at any

rate in its phrasing, to minimize set-backs and

failures. The operation orders, not greatly

unlike our own, contain specimens of every

nature, from those for a full-dress attack like

that which wrested Mont Kemmel from its

French defenders on April 25, 1918, to others

concerned with minor movements and reliefs.

The gem of the collection is the register of

telephone conversations, with the hour

carefully noted, carried on by General von

Lossberg, the Chief of the Staff of the Fourth

Army (nominally commanded by Sixt von

Armin), with the chiefs of the staffs of the

corps in it, and with his colleague on the

left, the Chief of the Staff of the Sixth

Army. But more important still are those

with General von Kuhl (the Chief Staff

Officer of Rupprecht of Bavaria's group of

armies, of which the Fourth and Sixth

Armies formed part), and with Ludendorff.

The names of Hindenburg, Rupprecht and

Armin never appear, except that the Fourth

Army commander is mentioned in the diary as

inspecting troops. It is the staff officers who

meet in conference, who take decisions, notify

them as their own to their subordinates, and

direct the operations, not even attempting to

veil the actual procedure by the covering

phrase of "the Army Commander wishes...."

This pernicious system had been lately

described in detail by the well-known writer,

General von Moser, a division and corps

commander, in his book "Ernsthafte Plaudereien

uber den Weltkreig." He gives as an instance

that at Cambrai he fixed the date of the

counter-attack on Bourlon Wood for the 3rd

but one of his general staff telephoned behind

his back to the Army General Staff and got it

altered to the 9th. He records that a brother

general said to him, "I am fighting the

enemy-and the General Staff."

Further we find that the higher staffs

interfered in all sorts of petty detail and left little

initiate to their subordinates. Ludendorff

in particular interferes unceasingly in the

sphere of the Fourth Army; he discusses the

mounting of minor operations; such as the

capture of a village; he recommends that one

corps should support a neighbouring one with

its guns; he gives his advice as to how an

infantry brigade should carry out an attack.

Lossberg acts in a similar way, encroaching,

on the duties of the corps commanders in

respect of their divisions. Anything more

opposed to the British—and French—practice

could hardly be imagined; and, just like

Napoleon’s one-man system, it was bound to

fail when a series of real crises arose and the

stage manager could not be everywhere at

once.

After the complete proof that Hindenburg

was but a figurehead the most interesting

revelation, at any rate as regards the fighting

in the spring of 1918, is that Ludendorff appears

to have been by no means an audacious

commander, the "hazardeur" risking all on a

decision, or the animator of the failing courage

of the troops and leaders. One finds him dealing

out the divisions from his reserve with

parsimony and regret, in insufficient number

to achieve a real success, or even to exploit an

advantage; and at last, when a few are

extracted from him, they arrive too late to

effect anything of value. Far from inspiring

his subordinates with the offensive spirit, he

showers counsels of prudence on them; and to

crown all we see him actually preventing an

exploitation of the victory of Kemmel, which

to many in France seemed the beginning of

the end, and warning the Fourth Army to

stand fast and organize a line of resistance to

meet the counter-stroke which the British will

be sure to deliver. Obviously the German

official account of first Ypres published in

1917 had not been compiled in vain. Finally,

on April 29 Ludendorff loses heart; he has

"the impression that the attack is not

developing favourably" Lossberg reports

that "the defence is too solid and too well

distributed in depth...... the operation presents

no chance of success. Better stop it." And

Ludendorff concurs.

Sydney Morning Herald

11/4/31

BATTLE OF THE LYS

Some Recollections.

(BY ALEX. SCOTT)

For various reasons the battle of the Lys.

which began on April 9, 1918, has never

received from historians the attention that

it deserves. This phase of the great German

offensive has been dwarfed by the colossal a

scale of Michael’s Day, when the assault

was made by 63 divisions. By comparison,

the Lys battle seems a mere side-show, for

the attack opened with only nine divisions.

And yet, when a careful survey is made of

the causes which eventually led to the a

down-fall of the German plans on the Western

Front, the 9th of April is a date of vital

significance.

In the original scheme this second attack,

known as "St. George," was to have been

very much more extensive, taking in the

whole Lens-Ypres sector (about 24 miles),

with Hazebrouck and its railway system as

the objectives. But "Michael" had used

up the German reserves so greedily that

when it was decided to carry on with

"George," troops could only be found for a

very much smaller edition of the plan,

extending from Givenchy to Armentieres, a

front of eleven miles. Yet at the outset

it looked as though the luck which had

shrouded "Michael'’ with a protecting mist

on March 21, was again fighting on the side

of the enemy. The front attacked on April

9 was held on the British right by the 55th

Division, on the left by the 40th; the centre

six miles near Neuve Chapelle were guarded

by the Portuguese, originally with two divisions,

on the night of 8th April actually

with only one. For one division had been

taken out, and the other was to have been

relieved on April 10 by two British divisions,

the 50th and the 51st. Pending relief, the

only stiffening allowed the weakened

Portuguese was provided by dismounted troopers

of King Edward's Horse and by the Corps

Cyclist Battalion. When the blow fell on

the morning of April 9 the Portuguese

disappeared. Some were seen riding the

bicycles of the Corps Cyclists; how far the others

ran has never been settled, nor does it matter

now. But in assessing the blame for

the debacle let it be remembered that the

Portuguese were asked to do the impossible.

So far as I am aware, no one at Army

Headquarters was shot for leaving six miles of

front in the care of a solitiary division, which

not even the kindest critic would have called

first-class troops.

VAGUE INSTRUCTIONS.

When the storm broke the 5lst Division was

in reserve just north of Bethune, licking

its sores, and trying to make good the losses

sustained in the original offensive. When

the orders were received to relieve the

Portuguese, for some obscure reason the Jocks

laughed, and said that this must be a "cushy"

bit of line It may have been: we never

reached it. By 9 o’'clock on the morning of

the attack all our carefully drafted orders for

relief were so much waste paper. Instead,

we were on the move to fill a gap of

unknown width. In the classic phrase "the

situation was obscure" boiled down. the new

operation orders were. "Go forward till you

bump something."

Fortunately the 55th Division held fast to

Givenchy, and with that flank firm, by the

evening of April 9 a line had been gradually

stretched along the river Lawe, linking

up with the 50th Division at Lestrem. But

in that one day a front of six miles in width

and three in depth had been lost.i t is

now clear from German documents that

the case and rapidity of this advance

influenced the judgment of Ludendorff One

frank historian even goes as far as to

that the Portuguese saved their Allies by

running away. LndendorH, instead of using

all his available forces to continue his thrust

across the Lys against Hazebouck, wasted men

and time (neither of which he could spare)

by following up the vanished Portuguese. The

gains in ground were spectacular, but useless

for his main purpose.

From Bethune the river Lawe runs almost

due north, while the continuation of the La

Bassee canal stretches north-west. The ground

in the "V" formed by the river. and the

canal is perfectly fat, a network of ditches

and hedges In this maze for three days the

opposing forces played a grim game of blind

man's buff, the stakes being their lives. For

some reason the aeroplane activity was under

normal, and because observation was so

difficult, or because the artillery had not been

given time to come round from the Amiens

salient, the gunfire was also less than it had

been on many days of the earlier attack But

what the fighting lacked in artillery was more

than made up by the fierce hand-to hand

encounters of the infantry And some

extraordinary things happened. All the reserve

dumps of ammunition behind the Portuguese

sector had been lost: to keep Lewis and

machine guns supplied transport driver.

trusted to the screen of hedges, and in places

drove their limbers in broad daylight to within

half a mile of the front line. The impudence

of the performance was its best safeguard

BACKS TO THE WALL.

Day by day the struggle extended on the

northern flank; by April 12 the original 11-

mile front had become 30, and Armentieres

had fallen. It was on April 12 that Haig

issued his famous message with its ominous

sentence "With our backs to the wall, and

believing in the justice of our cause each one

of us must fight on to the end." A strange

Army Order, which, curiously enough, had not

the depressing effect on the troops that one

night have expected. I wonder what we would

have thought had we known that the Field-

Marshal's holograph draft concluded. "But

be of good cheer, the British Empire must

win in the end" and a revising pencil struck

this sentence out!

In the 51st Division two brigades got such

a hammering that their combined strength

was less than one good battalion. So

desperate did the situation become that a

composite force was hastily formed under the

C.RE. This motley brigade included transport

drivers, quartermasters’ staffs, bandsmen.

Canadians who were employed on railway

construction, and some R.E's who were gas

protector specialists. This ragtime army was

pushed into the melee; what is even more

remarkable, it not only held its own, but pushed

the enemy back 700 yards. Yet every day

the pressure increased. It is recorded that

on the 14th. Haig called for more help from

the French Foch replied, "la bataille du nord

est finie." As things turned out, he was

right, but the Germans did not agree with

Foch until a fortnight later.

War is full of incongruities, and in my

experience the incongruous incidents are

remembered most vividly. I can still see some Jocks

on the first night of the battle leaving the

Germans to look after themselves, and not

only rounding up stray cows from abandoned

farms, but milking them. The next evening

an orderly came into our headquarters, and

said he had seen a young girl in the village of

Locon, then practically in the firing-line. We

had believed the area to be cleared of civilians

48 hours earlier. When we went to investigate

we found an old man lying in bed,

dead. In their excitement his neighbours

had gone off and left the daughter behind.

Like a dog on its master’'s grave, she now r

refused to leave, at least not till her father

had been buried. It was a scene worthy of

Dore. Three of our headquarters batmen dug a

grave by the light of flares from the enemy

lines, undismayed by an occasional shell

bursting close at hand. In the middle of

the night we gave the old Frenchman a

decent Highland funeral, good Catholic though

he may have been, and his daughter went away

to the French mission almost comforted.

Before carefully locking up me (which was

utterly destroyed by shellfire next morning)

she took a ham down from the rafters, and

insisted on the batmen accepting the gift.

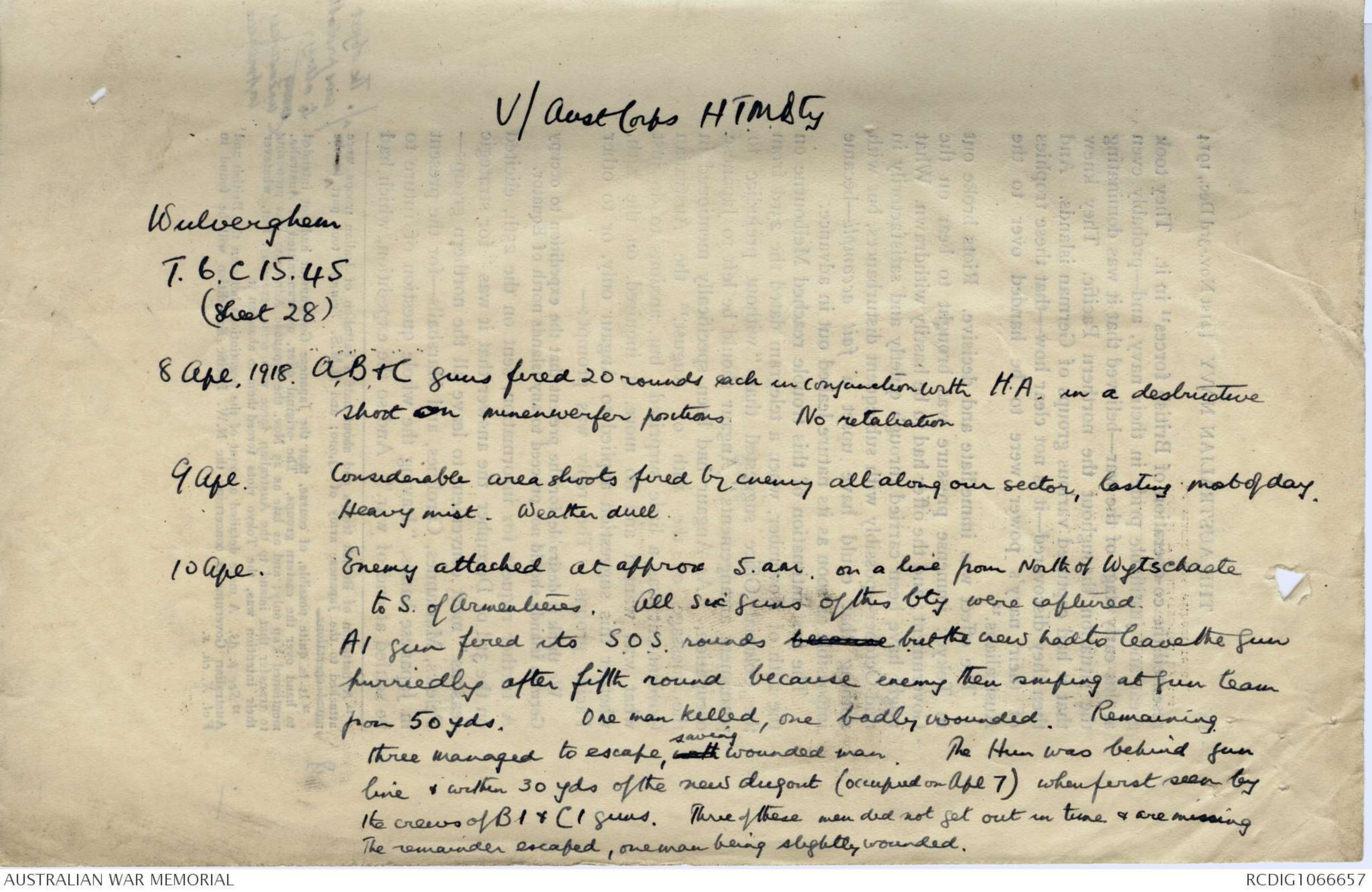

V/Aust Corps HTMBty

Wulverghem

T 6.C15. 45

(Sheet 28)

8 Apl. 1918. A.B. &C guns fired 20 rounds eich in conjunction with H.A. in a destructive

shoot on minenwerfer positions No retaliation

9 Apl. Considerable area shoots fired by enemy all along our sector, lasting most of day.

Heavy mist. Weather dull.

10 Apl. Enemy attacked at approx 5. a.m. on a line from North of Wytschaete

to S. of Armentieres. All six guns of this bty were captured.

AI gun fired its S.0.S. rounds because but the crew had to leave the gun

hurriedly after fifth round because enemy then sniping at gun team

from 50yds. One man killed, one badly wounded. Remaining

three managed to escape, with saving wounded man. The Hun was behind gun

line & within 30 yds of the new dugout (occupied on Apl 7) when first seen by

the crews of B1& C1 guns. Three of these men did not get out in time & are missing

The remainder escaped, one man being slightly wounded,

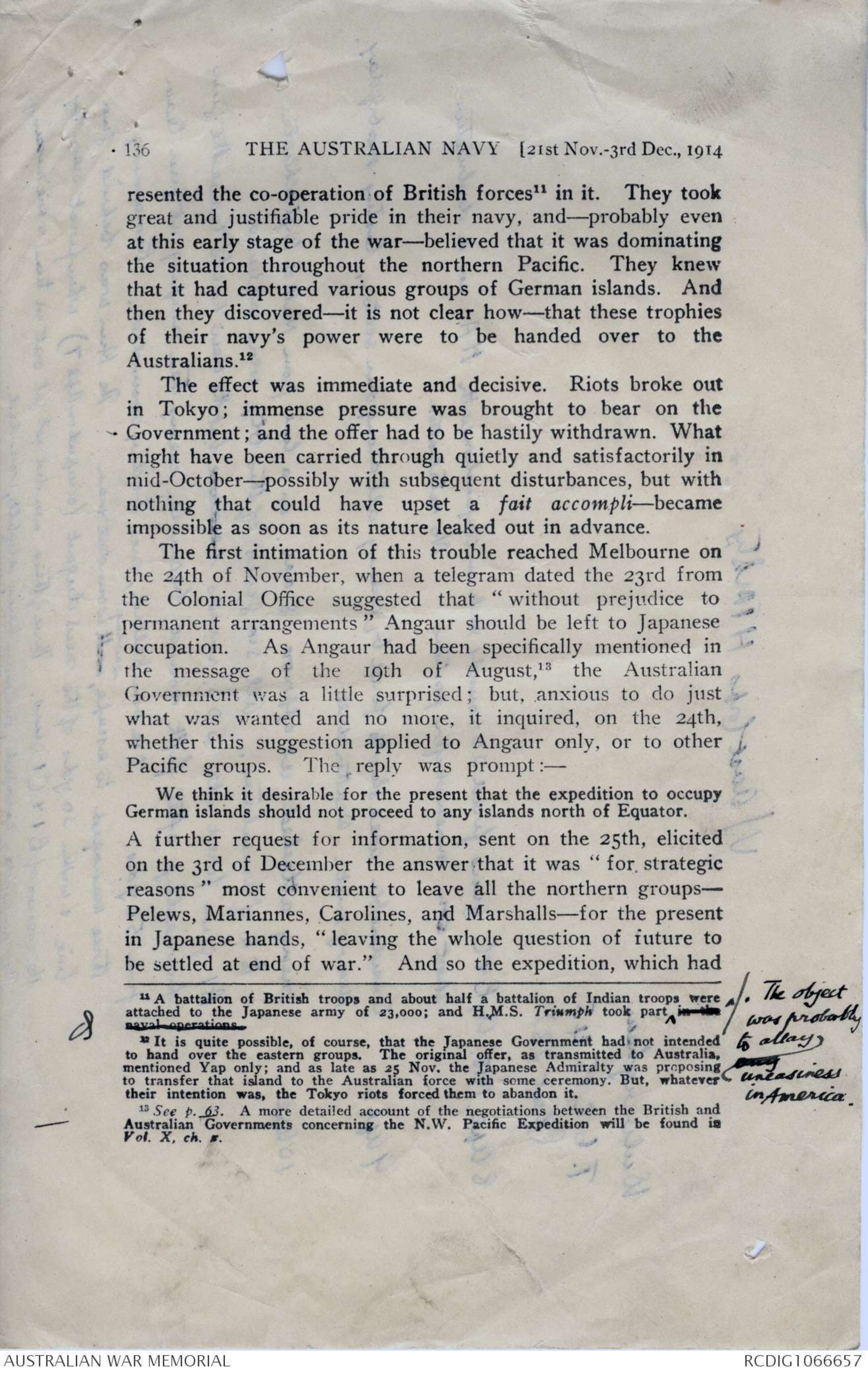

THE AUSTRALIAN NAVY (21st Nov-3rd Dec, 1914

136

resented the co-operation of British forces11 in it. They took

great and justifiable pride in their navy, and -probably even

at this early stage of the war—believed that it was dominating

the situation throughout the northern Pacific. They knew

that it had captured various groups of German islands. And

then they discovered—it is not clear how—that these trophies

of their navy's power were to be handed over to the

Australians.12

The effect was immediate and decisive. Riots broke out

in Tokyo; immense pressure was brought to bear on the

Government; and the offer had to be hastily withdrawn. What

might have been carried through quietly and satisfactorily in

mid-October—possibly with subsequent disturbances, but with

nothing that could have upset a fait accompli—became

impossible as soon as its nature leaked out in advance.

The first intimation of this trouble reached Melbourne on

the 24th of November, when a telegram dated the 23rd from

the Colonial Office suggested that "without prejudice to

permanent arrangements" Angaur should be left to Japanese

occupation. As Angaur had been specifically mentioned in

the message of the 10th of August,13 the Australian

Government was a little surprised; but, anxious to do just

what was wanted and no more, it inquired, on the 24th,

whether this suggestion applied to Angaur only, or to other

Pacific groups. The reply was prompt:-

We think it desirable for the present that the expedition to occupy

German islands should not proceed to any islands north of Equator.

A further request for information, sent on the 25th, elicited

on the 3rd of December the answer that it was "for strategic

reasons" most convenient to leave all the northern groups-

Pelews, Mariannes, Carolines, and Marshalls—for the present

in Japanese hands, "leaving the whole question of future to

be settled at end of war." And so the expedition, which had

11 A Battalion of British troops and about half a battalion of Indian troop;s, were

attached to the Japanese army of 23,000; and H.M.S. Triumph took part,^

[[*The object

was probably

to allay

uneasiness

in America,*]]in the navel operations

12 It is quite possible, of course, that the Japanese Government had not intended

to hand over the eastern groups. The original offer, as transmitted to Australia,

mentioned Yap only; and as late as 25 Nov. the Japanese Admiralty was proposing

to transfer that island to the Australian force with some ceremony. But, whatever

their intention was, the Tokyo riots forced them to abandon it.

13 See p. 63—S. A more detailed account of the negotiations between the British and

Australian Governments concerning the N.W. Pacific Expedition will be found in

Vol. X. ch. s.

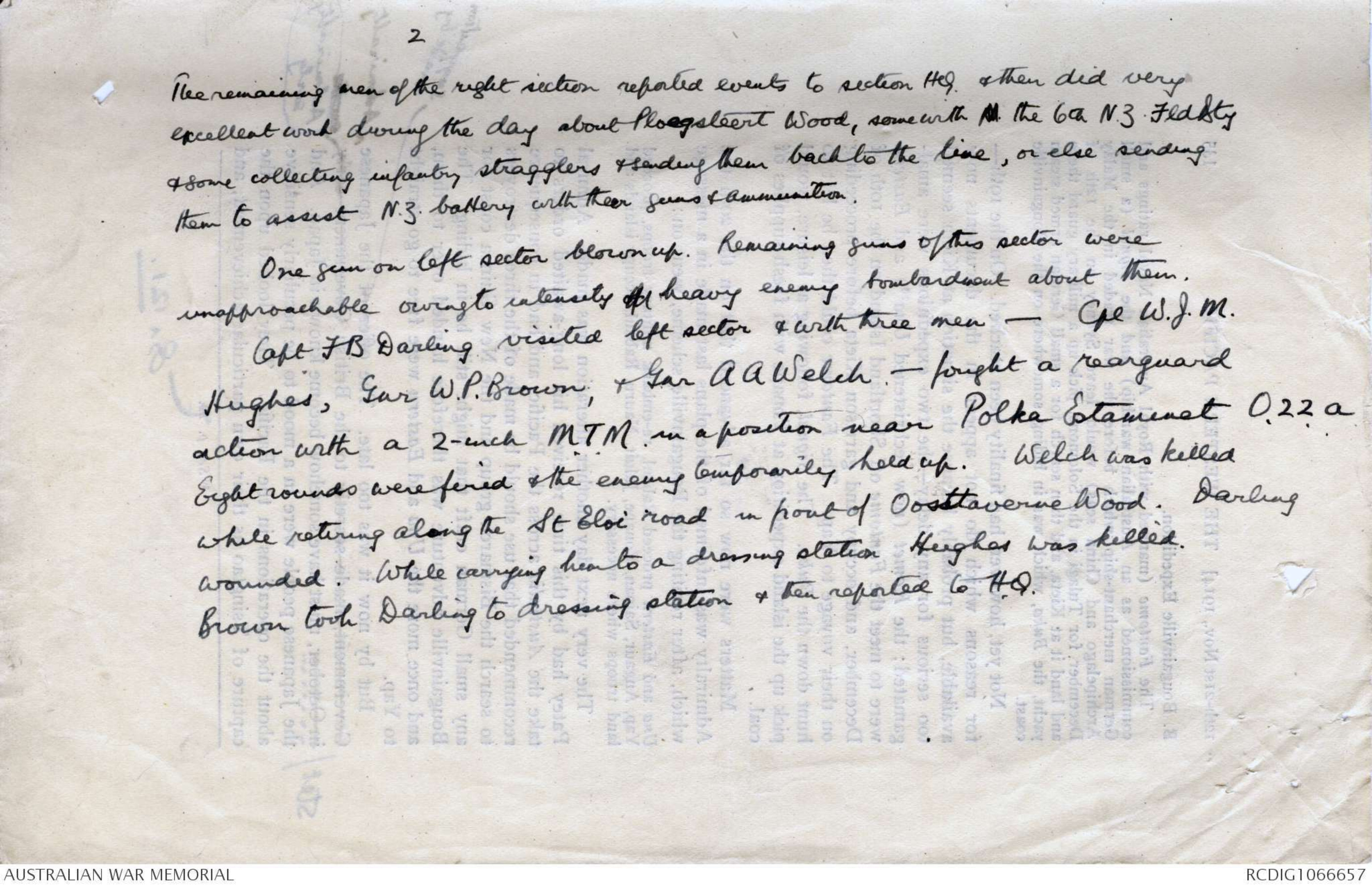

2

The remaining men of the right section reported events to section HQ. &then did very excellent work during the day about Ploegsteert Wood, same with A the 6th N.Z. Fld Bty

& some collecting infantry stragglers & sending them back to the line, or else sending

them to assist N.Z. battery with their guns & ammunition,

One gun on left sector blown up. Remaining guns of this sector were

unapproachable owing to intensity of heavy enemy bombardment about them.

Capt FB Darling visited left sector & with three men - Cpl W. J.M.

Hughes, Gun W.P. Brown; & Gun AA Welch - fought a rearguard

action with a 2-inch M.T.M. in a position near Polka Estaminet 0.22.a.

Eight rounds were fired & the enemy temporarily held up. Welch was killed

while returning along the St Eloi road in front of Oosttaverne Wood. Darling

wounded. While carrying hm to a dressing station Hughes was killed.

Brown took Darling to dressing station &f then reported to H.Q..

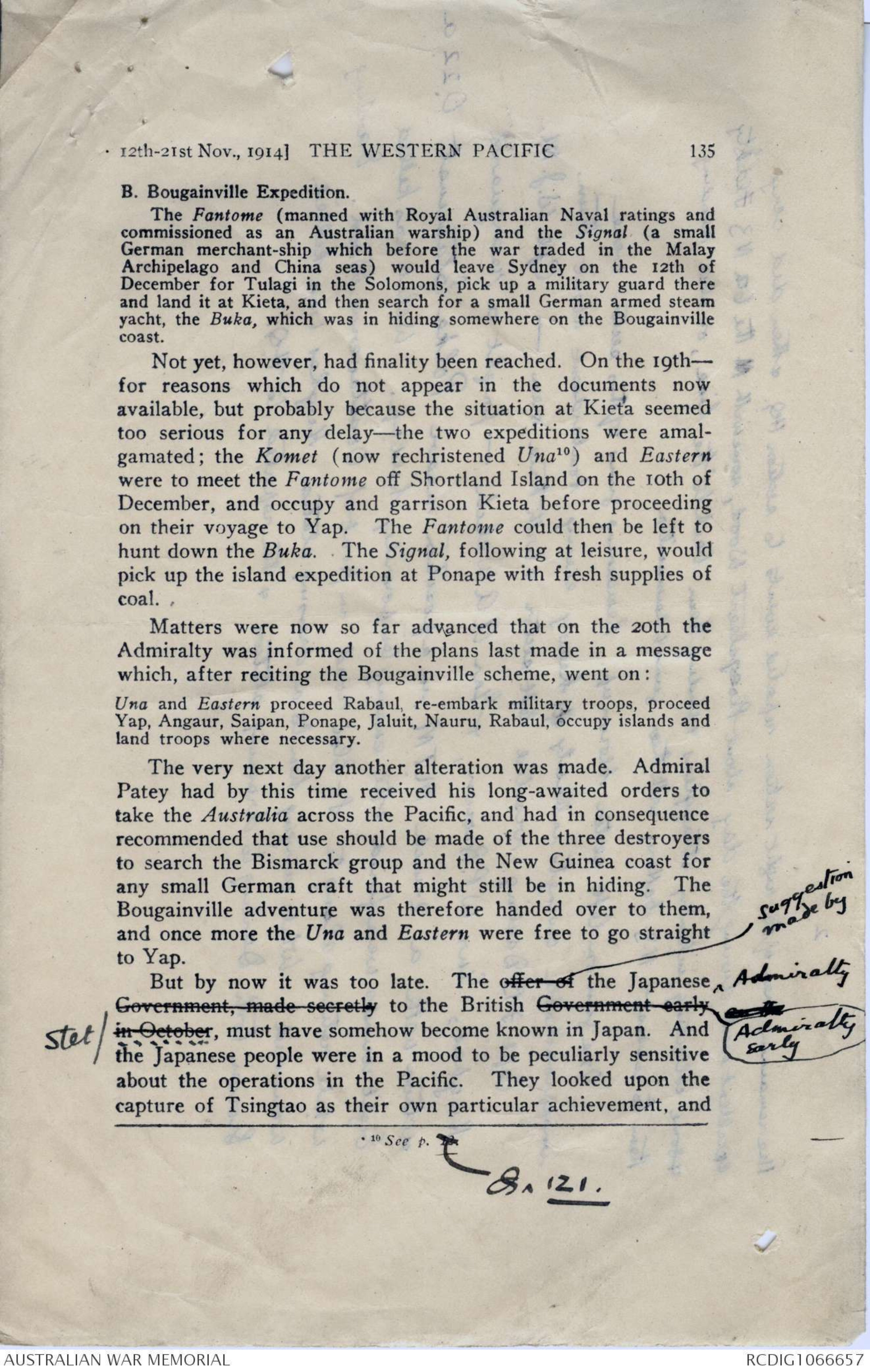

12th-21st Nov,1914] THE WESTERN PACIFIC

135

B. Bougainville Expedition.

The Fantome (manned with Royal Australian Naval ratings and

commissioned as an Australian warship) and the Signal. (a small

German merchant-ship which before the war traded in the Malay

Archipelago and China seas) would leave Sydney on the 12th of

December for Tulagi in the Solomons, pick up a military guard there

and land it at Kieta, and then search for a small German armed steam

yacht, the Buka, which was in hiding somewhere on the Bougainville

coast.

Not yet, however, had finality been reached. On the 19th—

for reasons which do not appear in the documents now

available, but probably because the situation at Kieta seemed

too serious for any delay—the two expeditions were

amalgamated; the Komet (now rechristened Unat10) and Eastern

were to meet the Fantome off Shortland Island on the 10th of

December, and occupy and garrison Kieta before proceeding

on their voyage to Yap. The Fantome could then be left to

hunt down the Buka. The Signal, following at leisure, would

pick up the island expedition at Ponape with fresh supplies of

coal.

Matters were now so far advanced that on the 20th the

Admiralty was informed of the plans last made in a message

which, after reciting the Bougainville scheme, went on:

Una and Eastern proceed Rabaul, re-embark military troops, proceed

Vap, Angaur, Saipan, Ponape, Jaluit, Nauru, Rabaul, occupy islands and

land troops where necessary.

The very next day another alteration was made. Admiral

Patey had by this time received his long-awaited orders, to

take the Australia across the Pacific, and had in consequence

recommended that use should be made of the three destroyers

to search the Bismarck group and the New Guinea coast for

any small German craft that might still be in hiding. The

Bougainville adventure was therefore handed over to them,

and once more the Una and Eastern were free to go straight

to Yap.

But by now it was too late. The offer of [[*suggestion made by*]] the JapaneseGovernment, made secretly to the British Government early [[*Admiralty early*]]

in October, must have somehow become known in Japan. And

the Japanese people were in a mood to be peculiarly sensitive

about the operations in the Pacific. They looked upon the

capture of Tsingtao as their own particular achievement, and

10 See p. 8^121

HN

noted

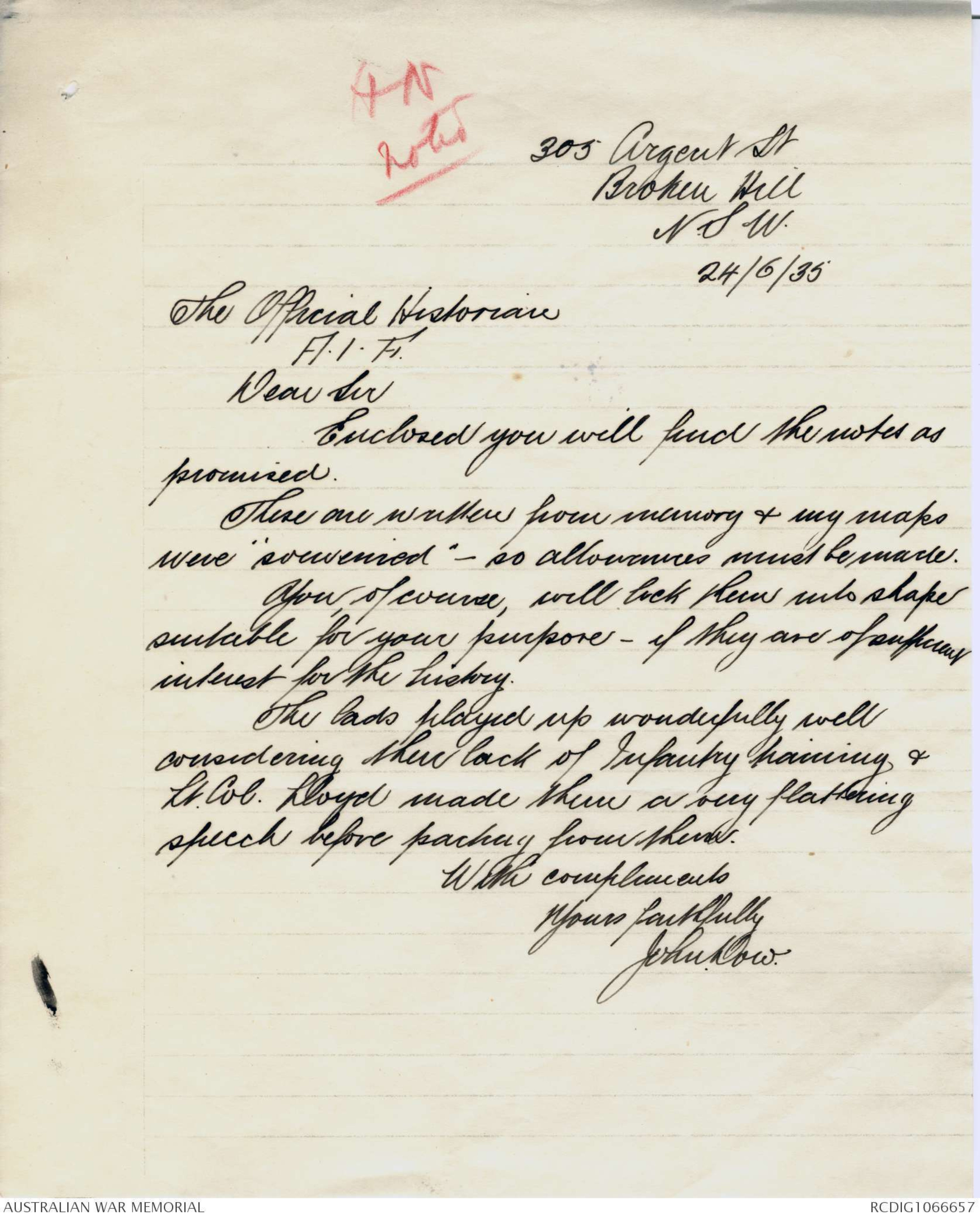

305 Argent St

Broken Hill

N.S. W.

24/6/35

The Official Historian

A.I.F.

Dear Sir

Enclosed you will find the notes as

promised.

These are written from memory & my maps

were souvenired - so allowances must be made.

You of course, will lick them into shape

suitable for your purpose - if they are of sufficient

interest for the history.

The lads played up wonderfully well

considering their lack of Infantry training &

Lt. Col. Lloyd made them a very flattering

speech before packing from them.

With compliments

Yours faithfully

John Dow.

noted

HN.

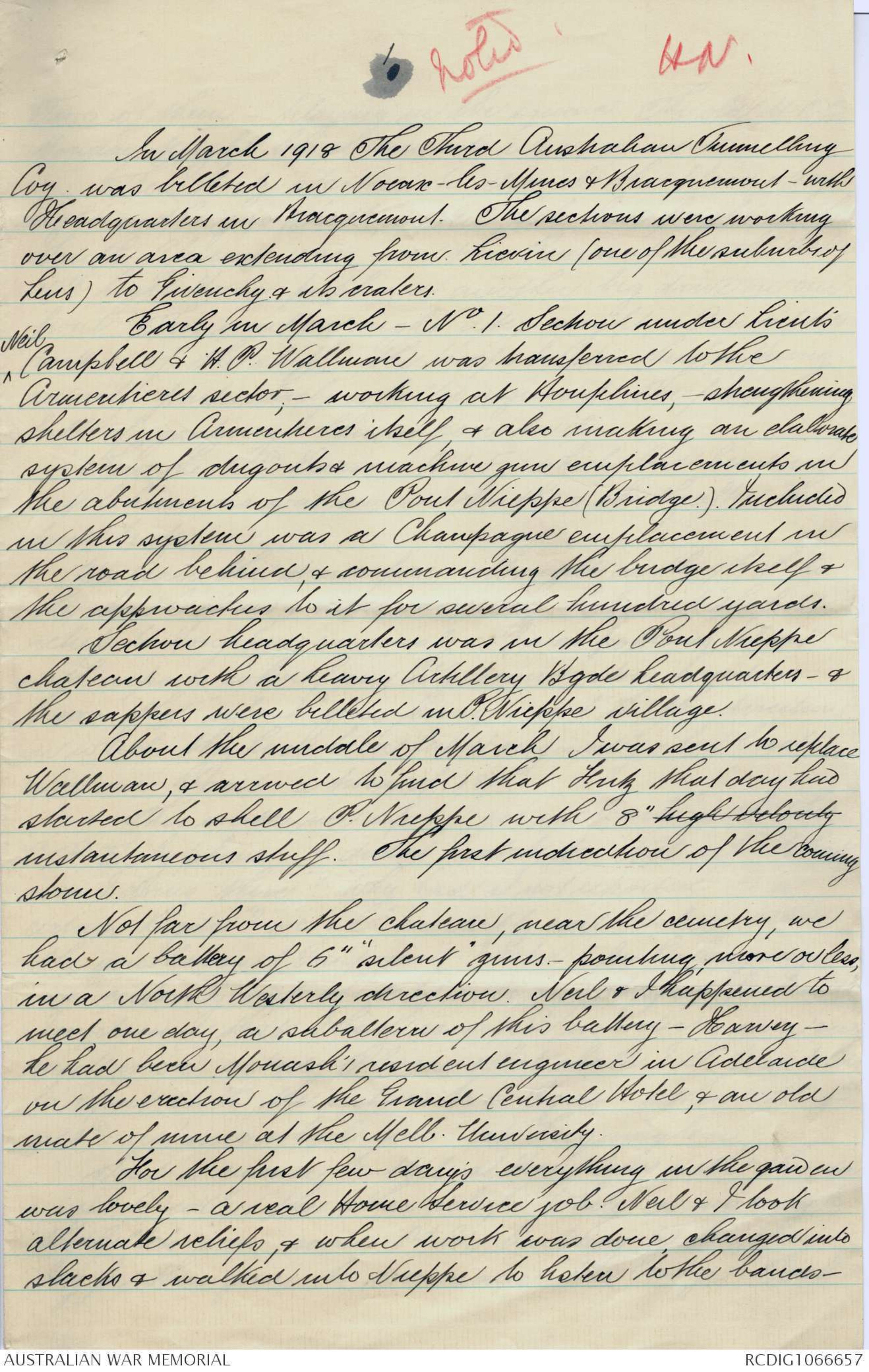

In March 1918 The Third Australian Tunnelling

Coy was billeted in Noeve-les Ypres & Bracquemout - with

Headquarters in Macquemont. The sections were working

over an area extending from Lievin (one of the suburbs of

Lens) to Givenchy & its craters.

Early in March - N. 1. Section under Lieuts

^Neil Campbell & H.P. Wallman was transferred to the

Armentieres sector, - working at Houplines, - strengthening

shelters in Armentieres itself & also making an elaborate

system of dugouts & machine gun emplacements in

the abutments of the Paul Nieppe (Bridge) Included

in this system was a Champagne emplacement in

the road behind, & commanding the bridge itself &

the approaches to it for several hundred yards.

Section headquarters was in the Paul Nieppe

chateau with a heavy Artillery Bgde headquarters- &

the sappers were billeted in P Nieppe village.

About the middle of March I was sent to replace

Wallman, & arrived to find that Fritz that day had

started to shell P. Nieppe with 8" high velocity

instantaneous stuff. The first indication of the coming

show.

Not far from the chateau, near the cemetry, we

had a battery of 6" "silent guns-pointing more or less,

in a North Westerly direction. Neil & I happened to

meet one day, a subaltern of this battery - Harvey.

he had been Monash' resident engineer in Adelaide

on the [[excavation?]] of the Grand Central Hotel & an old

mate of mine at the Melb University.

For the first few day's everything in the garden

was lovely - a real Home Service job Neil & I took

alternate reliefs, & when work was done changed into

slacks + walked into Nieppe to listen to the bands-

Sam scott

Sam scottThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.