Charles E W Bean, Diaries, AWM38 3DRL 606/251/1 - 1915 - 1936 - Part 10

3.

Telegraph) whom I had entertained at my headquarters in

France last September, and beyond him Sir Henry Wilson.

Opposite to me were Louis Botha, J.S.Sargent (the painter)

and Winston Churchill. The meal passed amid a loud buzz

of conversation and laughter and without restraint of

any kind. Contrary to custom the two toasts came on

before, and not after the dessert, and before the Port

was served. When the King rose to speak the whole

company, including the ladies, rose also, and remained

standing while the King delivered his oration and until

President Wilson had completed his reply. The speeches

were brief, but dignified in tone and lofty in sentiment

and Wilson's mobile face and hands were a study to watch.

Cigars and cigarettes were served at the table, but the

ladies did not leave alone, being conducted by their

cavaliers straight into the Red Drawing Room, all the

guests following. All the men smoked there and coffee

was served. Here three groups were formed, respectively

around the King, the Queen and Mr. and Mrs. Wilson; most

of the guests were presented to each in turn. I had

just five minutes with the King and the President, but

over ten minutes with the Queen, who talked about her son,

now at Aust.Corps H.Q. and was most enthusiastic in

praise of Australia and her soldiers, many of whom she

had met at Windsor Castle. I was greatly surprised to

find that Her Majesty spoke with avery strong foreign

accent. I had also a chat with the young and very

beautiful Duchess of Sutherland (whom I had already met

a couple of weeks ago at the Godleys) and who was "on

duty" as Mistress of the Robes. The Queen wore cloth

of gold and many magnificent diamonds, especially on

the corsage, including the Kohinor and the great Cullinan.

My five minutes with the President were quite formal.

He has a smile not unlike Roosevelt.

The company remained together until after midnight

no one withdrawing until the Royal Household retired.

The Duke of Connaught singled me out for special

attention and was very affable. Amongst others whom I

met for the first time or renewed acquaintanceship were

Lloyd George, Lord Rayleigh, Asquith, Viscount French,

Arthur Balfour, and Austin Chamberlain.

The King and Queen withdrew precisely at midnight

and then the distinguished company dispersed, with

memories of a thrilling function of unsurpassed brilliancy

and splendour which yielded not a dull moment.

I enclose a report of the two speeches and a full

list of the guests also the Invitation and Menu cards.

Note Kipling's autograph. I swopped it for one of

my own, which he insisted on my giving him. He entertained

me with three good stories about myself related to him

by others.

(Signed.) JOHN MONASH.

[*March

1918.*]

A CYCLE PATROL AND OPEN WARFARE.

by Capt C. H. Peters

38th Bn

A.I.F.

I have just finished reading a letter

written by the late General Sir John Monash to a friend,

describing the retreat of the Fifth Army in March

1918, and the re-establishment of the line of

defence by the Australian divisions.

Sir John's account is full, and may be

termed the "eagle's-eye" view, my reminiscences

the "worm's-eye" view, for in my then capacity of

Scout Officer, much of my duty was accomplished in

close contact with Mother Earth.

My memories of course include those of

marching forward along roads impeded by all the

rout of an army in retreat, the fleeing inhabitants;

I recall that the sight of "Aussies" going forward

gave heart to many of the fugitives, some of the

French country folk even turning back towards their

deserted homes; was it to guard them? Perish the

thought, no, it was confidence in the wearers of

the slouch hat engendered by previous contact with

the older Divisions of the A.I.F.

But all this may be read elsewhere, why

should I write it, rather should I tell of certain

individual experiences which I believe to be unique.

One, was the first A.I.F.Cycle Patrol

in the face of the enemy, this was undertaken by a

2.

patrol of five 38th Battalion Scouts, under my

leadership.

At that time, still Lieutenant, and still

38th Battalion Scouting and Raiding Officer, I, from

my long experience of this work, was the trusted

Scout for any special work required by Brigade and

Divisional Headquarters.

So it was that on March 27th ^1918 when the

38th Battalion A.I.F. was halted for the night at

[*?*] Authie, I received orders that made me realize that

for me there was no comfortable night's rest upon

the straw of the big barn. The day had been a

hard one for there is something exhausting about

travelling in railway trucks and then we had marched

some ten miles since detraining at Mondicourt.

General McNicholl G.O.C. 10th Brigade

A.I.F. had sent for me, and his instructions were to

get bicycles from somewhere and push on in the general

direction of the enemy, and send back and bring back

information, and if possible make contact with the enemy.

The General confessed himself without reliable

information, "Plenty of reports" he said, "but all

contradictory" and so he had determined to send out

and get all he could by his own scouts.

"How many? Peters?" I suggested my five

best scouts; signallers were despoiled of six push

bicycles and we set out riding always against the

3.

tide of confusion made by retiring troops, formed

and unformed, and the panicking French peasants; but

as we moved forward towards the enemy, this pressure

lessened and military order was found here and there.

But still cross-roads of importance were being shelled

and there confusion was confounded.

Villages were approached cautiously, then

cycles went into the ditch and a detail of two

guarded them while three accompanied my careful

approach to the village, as the men in the successive

villages were identified as "Tommies" so we regained

our bicycles and pressed on.

At each village, information was sought, but

without securing anything useful and authoritative,

even officers, when found, were possessed of only

confused and unreliable information.

Perhaps ten such villages and so many barraged

cross roads wore covered, then when approaching

Hebuterne by scouting methods, we saw the silhouette

of sentries with wide-brimmed hats, not "Aussie"

hats, surely not "Yanks", no, 'twas the New Zealand

Rifles, and the sight of these fine soldiers, admitted-

ly the best in France, made me feel that here I was

in contact with the front line.

From the sentry I secured the location of the

Divisional Headquarters, and found them in a

chateau, then from the busy staff got information,

4.

plenty of it, accurate too, though they had only just

moved down to that area.

My maps were marked, information recorded

and suggestions for a point of junction with their

flank made, and then with all speed back in the

direction Authie. No difficulty now, we knew the

villages were not hostile, we were with the current

that set so steadily toward the West.

The return to Authie was made an hour

after dawn, but our billets were deserted, Brigade

Headquarters had moved, and so down the road in the

direction of Franvillers, until we caught up with a

bus-column, scores of London busses crowded with

Australian soldiers, this was a novelty.

I found General McNicholl, and proffered

my maps, notes and reports proudly, feeling that the work

had been well done. But there came the rub; while

we were away, orders had come for us to move to

Franvillers, about fifteen miles to the South, and

from there to face east and move till we held up the

enemy. And so to my proffering of the results of

the night's duty came the answer "No use, sorry, but

we are away off that area, and very busy about the

place to which we are going."

And so the night's adventure resulted in

little except that we had performed the first

5.

A.I.F.Scouting Patrol on Cycles, a romantic and

memorable night's work.

Open Order Fighting March 1918

HEILLY AND MERICOURT-RIBEMONT.

[*Chap VIII p.30

& Chap VII p?*] But the scouts had yet another major part

to play in that day's operations which were in

the, to us novel, but really the old traditions of

Open Warfare.

The 38th Battalion de-bussed at Franvillers

on the heights and descended into the valley of

the Ancre and passing through Heilly assumed

artillery formation, for the approaches to this

village were under long distance artillery fire,

but these shells were avoided without casualties.

From Heilly the movement was in open order

with the scouts, about eighteen in number, as a

screen about three quarters of a mile in advance

of the main body, with connecting files for message

carrying.

Here came the scouts' opportunity to do their

part in the spirit of Field ServiceRegulations,

ground and cover was were examined and exploited and

outside Mericourt was discovered a series of old

French trenches revetted with fasxines, later a deep

valley revealed a barbed-wire enclosure, a Prisoner

of War Compound with buildings, all of which merited

6.

what proved to be a useful examination.

On up the hill to Marrett Wood, and through

the wood to its Eastern edge, 'twas from that height

we first sighted the enemy between one and two

miles distant, moving forward in small groups,

evidently an advance guard formation, but without

a screen of scouts.

This information conveyed to the C.O. 38th

brought an order to open fire and demonstrate

force as much as possible, then to fall back upon

the main body, which was consolidating upon the

Old French Trenches.

Rapid fire from constantly changed positions

inside the Eastern edge of Marrett Wood had the

effect of checking the German advance and later, after

we had withdrawn, of concentrating much artillery

fire upon the empty wood.

While falling back, the prisoner-of-war compound

was visited and several bags of rations were brought

back and contributed to the immediate popularity of

the Scouts on their rejoining their comrades.

A comic opera touch was provided by the discovery

in the compound of a store of costumes, evidently

the "props" of an entertainment troupe, and so,

arranged some as top-hatted gentlemen - London policemen

- ladies in evening dress - others in pyjamas and

7.

and nightdresses, the returning scouts puzzled

their comrades who believed the apparitions to be

some more fugitive French folk.

The next day saw a race for the elevated

position of Marrett Wood, which soon after its

occupation by the 38th was strongly attacked by

a German force which was repulsed.

March 26th and 27th were red-letter days for

the 38th scouts, their first taste of open warfare,

but there was much more to be done in the weeks

that followed, when the scouts' work assumed an added

importance and usefulness compared with the old

trench warfare days.

Charles H. Peters

Capt

38th Bn A.I.F.

3/1/34

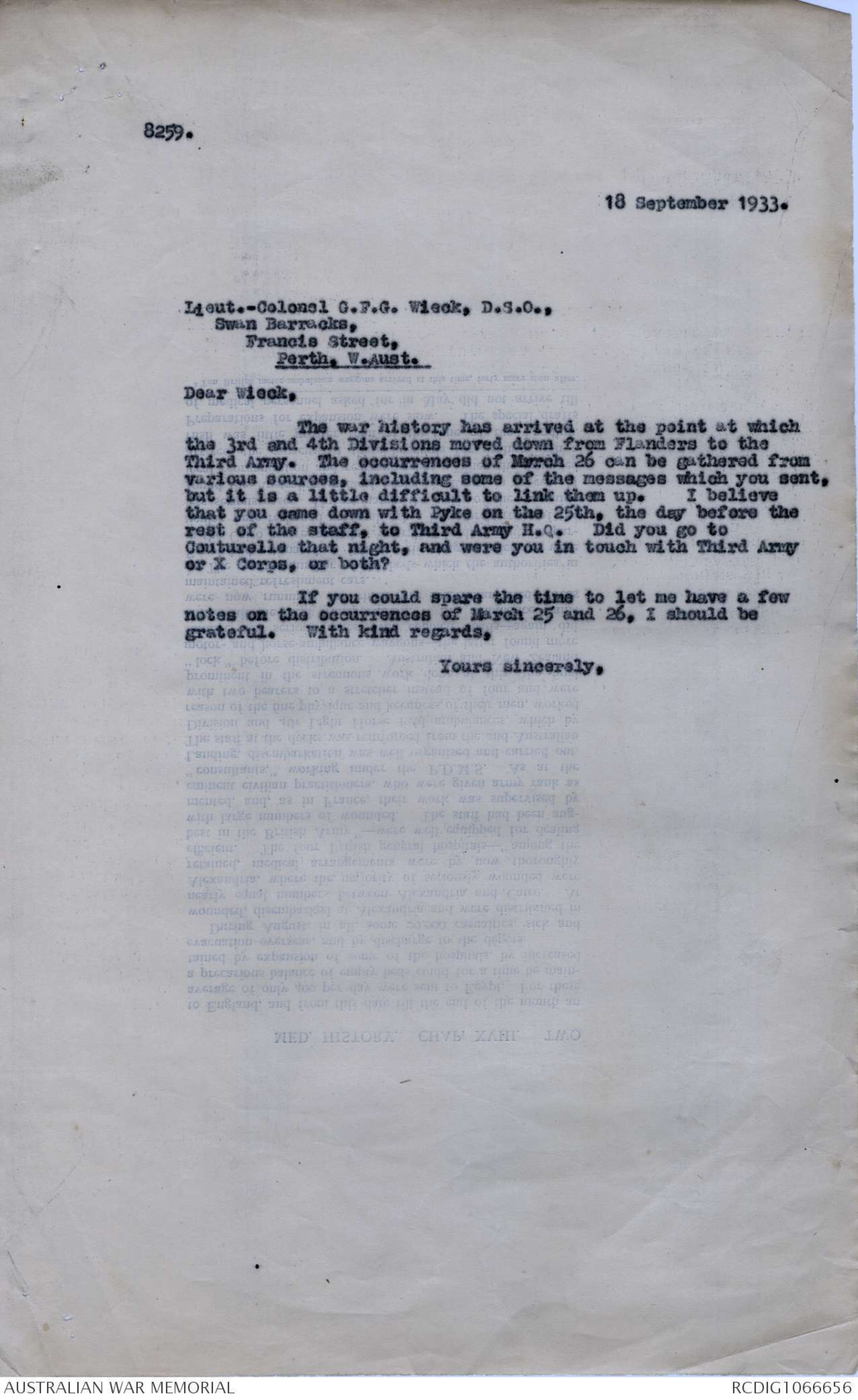

8259.

18 September 1933.

Lieut.-Colonel G.F.G. Wieck, D.S.0.,

Swan Barracks,

Francis Street,

Perth, W.Aust.

Dear Wieck,

The war history has arrived at the point at which

the 3rd and 4th Divisions moved down from Flanders to the

Third Army. The occurrences of March 26 can be gathered from

various sources, including some of the messages which you sent,

but it is a little difficult to link them up. I believe

that you came down with Pyke on the 25th, the day before the

rest of the staff, to Third Army H.Q. Did you go to

Couturelle that night, and were you in touch with Third Army

or X Corps, or both?

If you could spare the time to let me have a few

notes on the occurrences of March 25 and 26, I should be

grateful. With kind regards,

Yours sincerely,

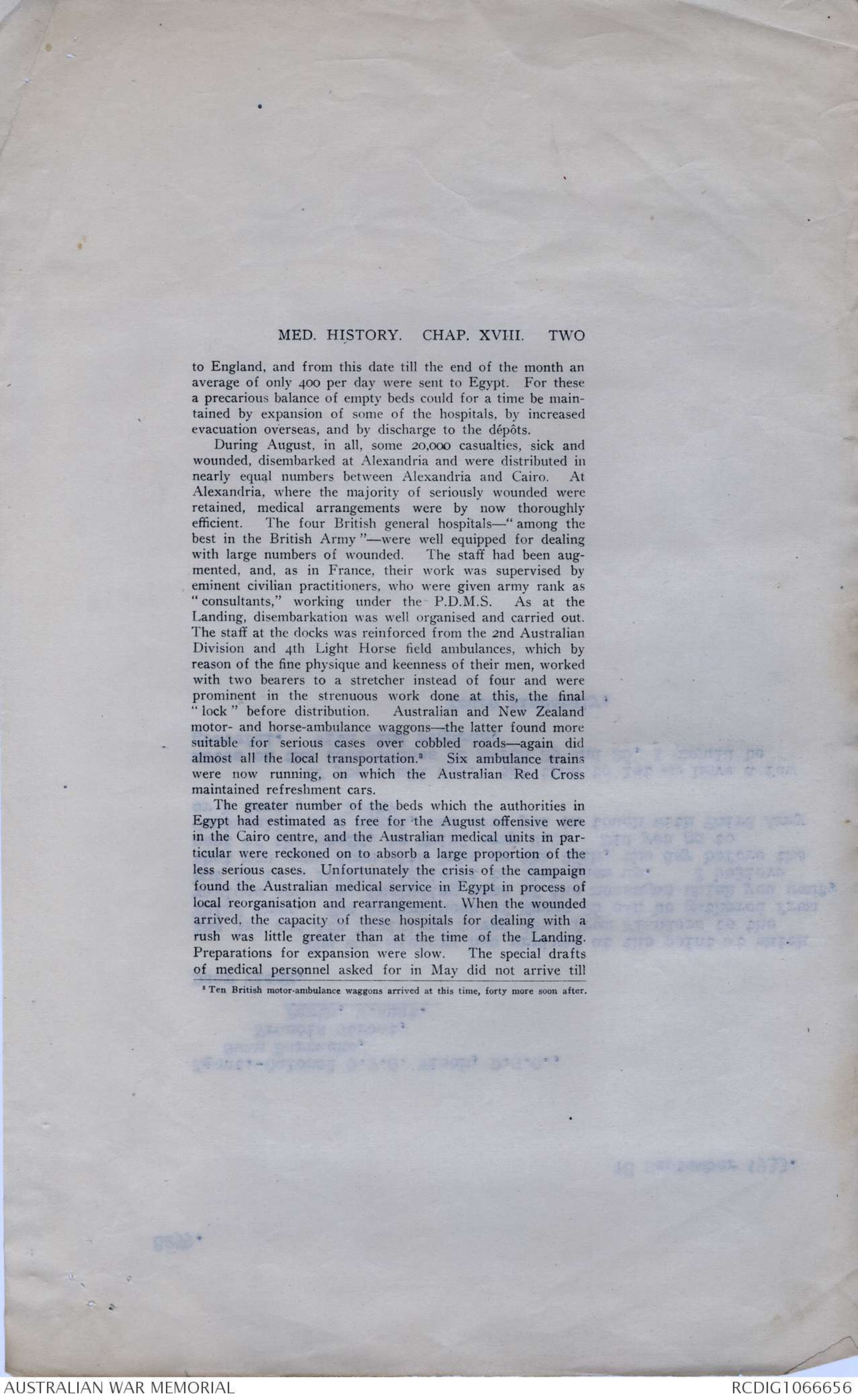

MED. HISTORY. CHAP. XVIII. TWO

to England, and from this date till the end of the month an

average of only 400 per day were sent to Egypt. For these

a precarious balance of empty beds could for a time be maintained

by expansion of some of the hospitals, by increased

evacuation overseas, and by discharge to the dépôts.

During August, in all, some 20,000 casualties, sick and

wounded, disembarked at Alexandria and were distributed in

nearly equal numbers between Alexandria and Cairo. At

Alexandria, where the majority of seriously wounded were

retained, medical arrangements were by now thoroughly

efficient. The four British general hospitals-"among the

best in the British Army "– were well equipped for dealing

with large numbers of wounded. The staff had been augmented,

and, as in France, their work was supervised by

eminent civilian practitioners, who were given army rank as

"consultants," working under the P.D.M.S. As at the

Landing, disembarkation was well organised and carried out.

The staff at the docks was reinforced from the 2nd Australian

Division and 4th Light Horse field ambulances, which by

reason of the fine physique and keenness of their men, worked

with two bearers to a stretcher instead of four and were

prominent in the strenuous work done at this, the fnal

"lock" before distribution. Australian and New Zealand

motor- and horse-ambulance waggons –the latter found more

suitable for serious cases over cobbled roads–again did

almost all the local transportation.3 Six ambulance trains

were now running, on which the Australian Red Cross

maintained refreshment cars.

The greater number of the beds which the authorities in

Egypt had estimated as free for the August offensive were

in the Cairo centre, and the Australian medical units in particular

were reckoned on to absorb a large proportion of the

less serious cases. Unfortunately the crisis of the campaign

found the Australian medical service in Egypt in process of

local reorganisation and rearrangement. When the wounded

arrived, the capacity of these hospitals for dealing with a

rush was little greater than at the time of the Landing.

Preparations for expansion were slow. The special drafts

of medical personnel asked for in May did not arrive till

3Ten British motor-amubulance waggons arrived at this time, forty more soon after.

Sam scott

Sam scottThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.