Charles E W Bean, Diaries, AWM38 3DRL 606/251/1 - 1915 - 1936 - Part 7

324 LORD MILNER AND THE UNIFIED COMMAND.

Milner* himself rather resented the idea that his responsibilities during the great

German offensive began and ended with the attainment of the unified command.

On 20th April, less than a month after the Doullens Conference, he ceased to be a

member of the War Cabinet and was sworn in as Secretary for War. From then to

the Armistice, in the words of General Smuts (no incompetent judge of such matters),

"his consummate handling of the War Office was undoubtedly one of the factors

which contributed materially to the Allied victory.” But great and many-sided as

were his services in this capacity, and especially those he rendered during the four

long months when, from April to the end of July, the fortune of the Allies remained

upon the razor-edge of fate, this three days’ visit to France, with its ceaseless energy

and unhesitating action, stands pre-eminent as an example no less of Milner’s

self-effacing patriotism, than of his high and courageous statesmanship. In it he took

upon himself a burden of responsibility than which none heavier was borne by any

man in the World War. For the second and final document, to which he and

Clemenceau (at his bidding) set their hands in the Mairie of Doullens, placed not only

the French and British but the Belgian, American and Italian troops on the Western

Front under the control of Foch. He believed that he could rely upon the support of

Lloyd George and the War Cabinet ; and in the event he was right. His action was

approved at once in London, and the proceedings at Doullens were ratified formally

eight days later at Beauvais by the representatives of all the Powers concerned.

The wisdom of his choice of Foch as generalissimo was speedily, and amply, proved.

But if his action had been questioned or repudiated, he would have had no delegated

powers, no official instructions, to justify it. Of specific authority he had none.

His only instructions were Lloyd George’s words over the telephone. With a standing

so insecure, a statesman mindful of his reputation might well have refused to commit

himself to any hasty decision. The near realities of shell-torn roads, shrivelled

trees, and riven walls might well have numbed the brain of a less prudent agent,

and robbed it of the power to register the sharp decisions which armed Milner to accept

personal responsibility then and there for a fundamental change of command, the

issue of which no man could foresee with any certainty.

Nor does it detract from the merit of his service to recall that all military

authorities, French, British and American, had attributed for two years past the

failure of the Allied arms chiefly to the want of unity of command upon the Western

Front. The fact remains that Milner did what other men had sought to do, and found

impossible ; and did it with such swift decision that even at this eleventh hour it was

still in time. For, on that same day, before the destroyer detailed to carry Milner

back across the Channel had cleared the harbour of Boulogne, Foch was bringing up

the French divisions which stayed the German advance on Amiens by a margin not

of days, but of hours. In the fire of instant peril all concerned were malleable to

the hammer-stroke of Milner’s will. Foch and Clemenceau were reconciled. Haig

accepted the change with alacrity ; and Pétain stood aside to let Foch step to the

front. This at Doullens on Tuesday, 26th March. But a fortnight, a week, even a

few days later. . . . .? If the enemy had struck no paralyzing blow meantime, who

can say that the old dissensions, the endless balancing of political loss against military

gain in the councils of the Allies, the national and personal rivalries in the field, would

not have revived ; that the one golden moment of opportunity would not have passed,

never to return ?

*Lord Milner died—unexpectedly and after a short illness - of encephalitis lethargica on 13th May, 1925, in his

71st year.

Le général Foch

est chargé par les gouvernements

britanniques et français de

coordonner l’action des armées

alliées sur

le front ouest. . Il s’entendra

à cet effet avec les

généraux en chef, qui sont

invités a lui fournir tous les

renseignements nécessaires

Doullens le 26 Mon 1917

Clemenceau Milner

The Times Photo.

THE DOULLENS AGREEMENT,

SIGNED BY M. CLEMENCEAU AND LORD MILNER.

Docts of Record.

THE NEW STATESMAN

Special Supplement

VoL. XVII. No. 419. SATURDAY, APRIL 23, 1921. ADDITIONAL PAGES

THE

ESTABLISHMENT OF “UNITY OF COMMAND"

A HISTORIC DOCUMENT

Very gradually the inner history of the war is coming to light. It will probably be many years before the

public is in possession of anything like the full truth concerning even the main political and military episodes

of the struggle. The reasons why information is still withheld are not “reasons of State,” but for the most

part personal reasons. As a Member of Parliament remarked the other day, if all the facts, as recorded in

official documents, are to be made public “ some war reputations will be blown sky-high.” It would indeed be

hardly too much to say that the reputations which would remain unspotted or undiminished would be very few and

far between. Most of the people who are in a position to enlighten the public would doubtless be willing to

publish some part of the truth, but generally there is some other part which they would prefer kept secret, and

thus very naturally arises a sort of official conspiracy of silence which only time will break down.

Meanwhile, the Repingtons and the Peter Wrights and the Filson Youngs give us their inevitably

tendencious and partial “ revelations.” No doubt much of what they tell us is true, but they have their heroes

or their enemies, and they write with so manifest a purpose that it is very difficult for the uninformed reader to be

sure what fraction or aspect of the truth he is really getting.

We print below a document about which such doubts cannot arise. It blasts no reputation, but it reveals

the precise and unchallengeable truth about one of the most crucial events of the war—the final act in the story of

the establishment of “ Unity of Command.” Previous attempts to attain this indispensable condition of victory

had broken down, mainly owing to the active or passive resistance of the French and British Commanders-in-Chief,

supported by certain politicians and military theorists in London and Paris. The great disaster of March 21st,

1918, however, and the apprehensions which it aroused, broke down all such obstacles. On arriving in France

Lord Milner found his task, as he describes, unexpectedly easy, and before he had left French soil on the day

of the decision, Foch was moving up the troops which, by a margin of hours, saved Amiens.

MEMORANDUM

TO THE CABINET BY LORD MILNER ON HIS

VISIT TO FRANCE, INCLUDING THE CONFERENCE

AT DOULLENS, MARCH 26TH, 1918.

The Prime Minister having asked me to run over

to France in order to report to the Cabinet

personally on the position of affairs there,

I left Charing Cross at 12.50 on Sunday, March 24th,

accompanied by Major Shawe, of the Rifle Brigade.

We were delayed some time at Folkestone, the boat

not starting till 4.45, and reached Boulogne about 6.30.

Colonel Amery was waiting at Boulogne with two of

the Versailles motors, and we went straight on to

G.H.Q. at Montreuil. Here I saw General Davidson,

who was just communicating on the telephone with

the C.G.S. when I came in. He gave me a brief sketch

of the situation, which had been developing very rapidly

and adversely during the day. From Montreuil I

was accompanied by Brig.-General Wake, a member

of General Rawlinson’s staff at Versailles, who was

returning to that place after having spent a day and

a half at G.H.Q. On the long journey from Montreuil

to Versailles he was able to give me a very full account

of all that had happened so far as it was yet known.

The great mystery was the breakdown of the Fifth

Army, which so far was not explained. Owing to

this Army being so much broken and communications

cut in all directions, it was difficult to make out exactly

what had happened, and it would take time to place

together the reports. Broadly speaking, however,

there was no doubt that this Army was shattered

and a breach effected in the Allied line between the

right flank of the Third Army and the French. This

did not mean, of course, that there was no more

resistance in that quarter. The retreating troops,

who had now been driven from the line of the Somme

below Peronne, were apparently still fighting at a

number of points and sometimes even counter-attacking,

but were no longer anything like an organised barrier

to the German advance. The rapidity with which this

Army had been driven from its strongly-prepared

positions will no doubt be explained in time. It

does not appear to have been due to any lack of gallant

fighting, and no doubt the German impact at this

point was quite tremendous, the attacking forces

probably outnumbering the defenders by at least

two to one. It was clearly useless to speculate with

our present knowledge about the causes or the exact

course of events in this quarter, but the effect of what

had happened on the general situation was, of course,

perfectly clear and did not need to be dwelt upon.

The journey from Montreuil to Versailles took over

six hours, including a stop of about three-quarters of

ii [SPECIAL SUPPLEMENT.] THE NEW STATESMAN APRIL 23, 1921

an hour at Abbeville, where we had some dinner, and

we did not reach General Rawlinson’s house at

Versailles till 2.30 a.m. A telegram from G.H.Q.,

dated 11.30 p.m., which we found on arrival, stated

that from the latest reports the general situation was

somewhat improved.

I was up at 7 the next morning, March 25th, and

after breakfast I saw Rawlinson. Wake gave us both

a connected account of what had happened during the

time he was at G.H.Q., illustrating it by a large map

which he had brought with him from there. This

was substantially, with some more detail, what I had

learnt from him the previous night. Soon after 9

I had a message from M. Clemenceau, to say that he

urgently wished to see me. I motored into Paris at

once, accompanied by Colonel Amery, and found

Clemenceau at the Ministry of War. He was in great

form and very full of fight, and, while fully realising the

gravity of the situation, showed not the slightest

sign either of despondency or confusion. Our interview

was not long, as he had a number of important matters

to attend to immediately. He told me that he thought

important decisions must be taken at once. His view

was that it was necessary at all costs to maintain the

connection between the French and British Armies,

and that both Haig and Pétain must at once throw

in their reserves to stop the breach which was in course

of being effected.

He said, among other things, it would be necessary

to bring pressure to bear upon Pétain to do more in

that direction. He evidently hoped that Haig would

be able to bring down more reserves from the north.

He was most anxious to go and meet the British and

French Commanders-in-Chief that afternoon, taking

General Foch and me with him. He heard that

General Wilson was arriving at Abbeville to meet

Haig, and he was trying to get them to come on to

Compiègne, Pétain’s headquarters, where we could

join them in the course of the afternoon. He told me

to hold myself in readiness to start at a moment's

notice on a message from him after 2 o’clock.

accordingly returned at once to Versailles, as I was

anxious to see Rawlinson again before leaving and

learn his views of the situation more fully than I had

had time to do in the early morning. While at Versailles

I had a message from Wilson at Abbeville asking me

to meet him there at 3 o clock, but as this message

did not reach me till 12.30, it was evidently impossible

to get to Abbeville by 3. As, moreover, I knew that

Clemenceau was trying to get Haig and Wilson to

come to Compiègne, and as I was in any case pledged

to Clemenceau, I determined not to change my plans.

I accordingly went to the Embassy in Paris at 2,

where I saw Lord Bertie, and waited there until just

before 3 I got a summons from Clemenceau. The

President of the Republic, Clemenceau, who was

accompanied by M. Loucheur, General Foch, and I,

then all motored to Compiègne, arriving a little before 5.

Petain met us there, but it had unfortunately been

impossible, as I had always feared, to get Haig and

Wilson to meet us also. A Conference was held at

Pétain’s headquarters between 5 and 7. The President

of the Republic was in the Chair, the others present

were Clemenceau, Loucheur, Pétain, Foch and I.

Pétain explained very clearly his view of the position.

He took a very pessimistic view of the condition of

the Fifth Army, which, he said, as an army had

ceased to exist and would have to be completely

reorganised. It had now been placed by Haig under

his (Pétain’s) orders. He was, he said, bringing up

from the south and west all the divisions he could

possibly spare to support and replace the débris of the

Fifth Army. Six divisions, which he had always

had in reserve close at hand to reinforce the British

right in case of necessity, were already heavily engaged

in the neighbourhood of Noyon, Roye and Nesle,

and he was bringing round nine more divisions—

mostly from the south but some from the north—which

would be pushed westward to meet the advancing

Germans, from Montdidier and Moreuil. This was all

he could possibly spare at the moment, though he

hoped to bring more presently, but he could not neglect

either the danger of the Germans pushing down the

Oise from about Noyon, nor a threatened attack in

the region of Reims. While not differing from General

Pétain’s strategic plans, General Foch evidently took

a somewhat different view of the situation. He thought

the danger of the great German push to break in between

the French and British in the direction of Amiens

was so formidable that risks must be taken in other

directions. Even more divisions must if possible be

thrown in, and, by a great effort, this might be done

more quickly than Pétain thought possible—even if

the relieving forces were thrown in in less complete

formation than under conditions of less extreme

urgency would be desirable. This at least was my

interpretation of his long and very energetic statement,

all the military details of which it was not possible

for me to follow. Poincaré and Clemenceau were

evidently in sympathy with Foch’s view of the necessity

of taking extreme measures with all possible rapidity,

and the latter now appealed to me to express my opinion

and especially to say what more I thought the British

on their side could do, in order to re-establish the

complete co-operation of the two Armies. I replied

that, of course, it was impossible not to agree in principle

with the views expressed, but that it would not be

justifiable for me to give an opinion as to the exact

course to be followed without having been able to

consult Haig and Wilson. It was most unfortunate,

though it could not be helped, that they were not

present, but I thought we must try to remedy this

at the earliest possible moment and have another

meeting, at which one or, if possible, both of them should

be present, next day. Clemenceau, agreed with this,

and it was accordingly decided that we should try to

arrange a meeting at Dury, just south of Amiens,

at 11 o’clock on the following morning, to which all

those present should come to meet the British generals.

Poincaré, Clemenceau, Loucheur, Foch and I then

returned to Paris, but before leaving Compiègne I had

a few minutes’ private conversation with Clemenceau,

in which I impressed upon him that, to the best of

my belief, the British Third Army, which seemed to

have stood magnificently together with the reliefs

which were being sent to it from the north, were already

doing all they could, and that I had some misgiving

whether Pétain on his side was prepared to take sufficient

risks in order to bring up all possible French

reserves, on which, as it seemed to me, everything

depended. He said that he agreed, but that Pétain

was already doing much more than he had originally

contemplated, and would, he believed, do more still.

He also agreed with me in sympathising with the

attitude of Foch.

I got back to Versailles at 9 o’clock and was very

happy to find that Wilson had just arrived from

Abbeville. Meanwhile, a message had arrived from

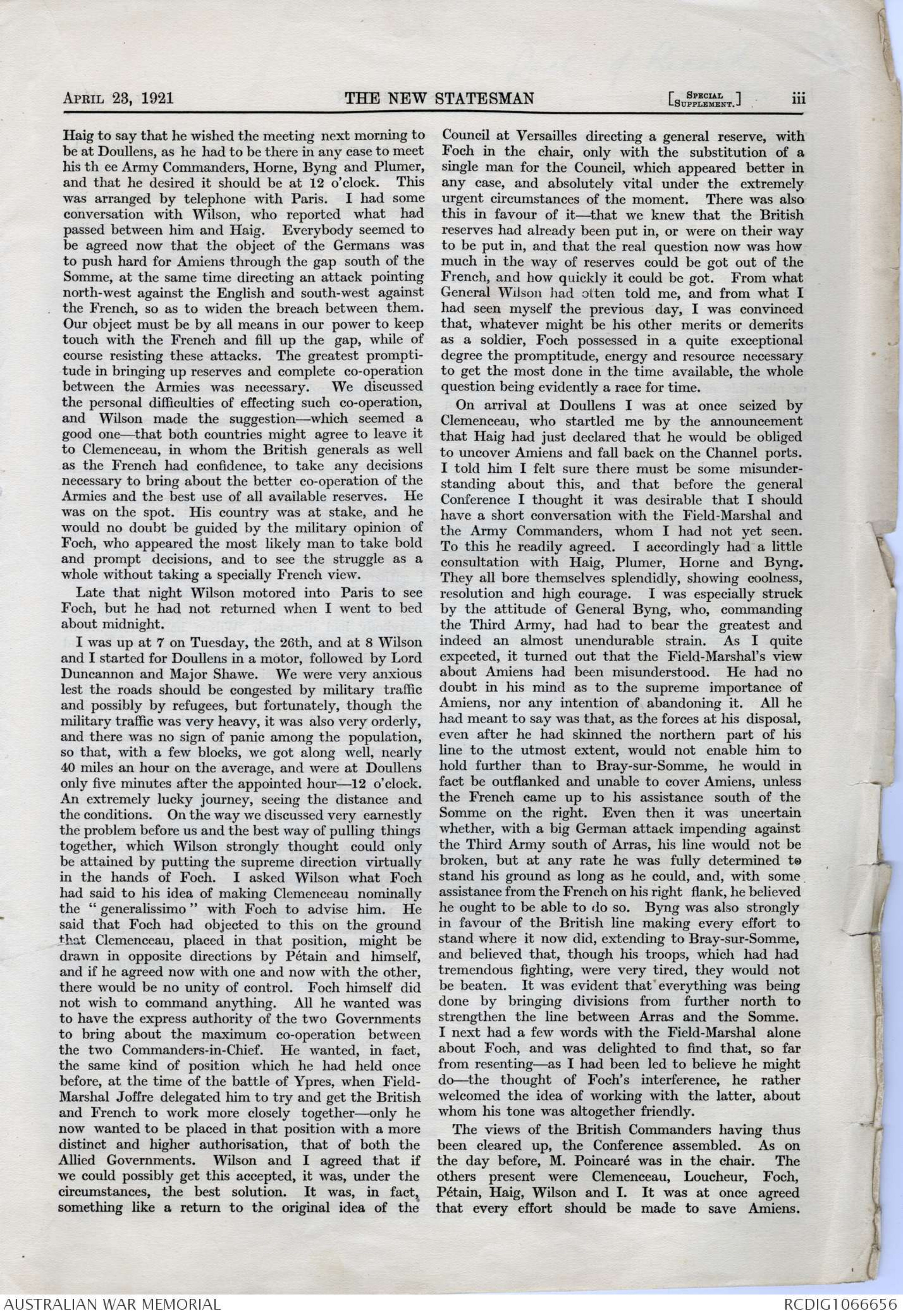

APRIL 23, 1921 THE NEW STATESMAN SPECIAL SUPPLEMENT. iii

Haig to say that he wished the meeting next morning to

be at Doullens, as he had to be there in any case to meet

his th ee Army Commanders, Horne, Byng and Plumer,

and that he desired it should be at 12 o’clock. This

was arranged by telephone with Paris. I had some

conversation with Wilson, who reported what had

passed between him and Haig. Everybody seemed to

be agreed now that the object of the Germans was

to push hard for Amiens through the gap south of the

Somme, at the same time directing an attack pointing

north-west against the English and south-west against

the French, so as to widen the breach between them.

Our object must be by all means in our power to keep

touch with the French and fill up the gap, while of

course resisting these attacks. The greatest promptitude

in bringing up reserves and complete co-operation

between the Armies was necessary. We discussed

the personal difficulties of effecting such co-operation,

and Wilson made the suggestion—which seemed a

good one—that both countries might agree to leave it

to Clemenceau, in whom the British generals as well

as the French had confidence, to take any decisions

necessary to bring about the better co-operation of the

Armies and the best use of all available reserves. He

was on the spot. His country was at stake, and he

would no doubt be guided by the military opinion of

Foch, who appeared the most likely man to take bold

and prompt decisions, and to see the struggle as a

whole without taking a specially French view.

Late that night Wilson motored into Paris to see

Foch, but he had not returned when I went to bed

about midnight.

I was up at 7 on Tuesday, the 26th, and at 8 Wilson

and I started for Doullens in a motor, followed by Lord

Duncannon and Major Shawe. We were very anxious

lest the roads should be congested by military traffic

and possibly by refugees, but fortunately, though the

military traffic was very heavy, it was also very orderly

and there was no sign of panic among the population,

so that, with a few blocks, we got along well, nearly

40 miles an hour on the average, and were at Doullens

only five minutes after the appointed hour—12 o’clock.

An extremely lucky journey, seeing the distance and

the conditions. On the way we discussed very earnestly

the problem before us and the best way of pulling things

together, which Wilson strongly thought could only

be attained by putting the supreme direction virtually

in the hands of Foch. I asked Wilson what Foch

had said to his idea of making Clemenceau nominally

the “ generalissimo" with Foch to advise him. He

said that Foch had objected to this on the ground

that Clemenceau, placed in that position, might be

drawn in opposite directions by Pétain and himself,

and if he agreed now with one and now with the other,

there would be no unity of control. Foch himself did

not wish to command anything. All he wanted was

to have the express authority of the two Governments

to bring about the maximum co-operation between

the two Commanders-in-Chief. He wanted, in fact,

the same kind of position which he had held once

before, at the time of the battle of Ypres, when Field-

Marshal Joffre delegated him to try and get the British

and French to work more closely together—only he

now wanted to be placed in that position with a more

distinct and higher authorisation, that of both the

Allied Governments. Wilson and I agreed that if

we could possibly get this accepted, it was, under the

circumstances, the best solution. It was, in fact

something like a return to the original idea of the

Council at Versailles directing a general reserve, with

Foch in the chair, only with the substitution of a

single man for the Council, which appeared better in

any case, and absolutely vital under the extremely

urgent circumstances of the moment. There was also

this in favour of it—that we knew that the British

reserves had already been put in, or were on their way

to be put in, and that the real question now was how

much in the way of reserves could be got out of the

French, and how quickly it could be got. From what

General Wilson had often told me, and from what I

had seen myself the previous day, I was convinced

that, whatever might be his other merits or demerits

as a soldier, Foch possessed in a quite exceptional

degree the promptitude, energy and resource necessary

to get the most done in the time available, the whole

question being evidently a race for time.

On arrival at Doullens I was at once seized by

Clemenceau, who startled me by the announcement

that Haig had just declared that he would be obliged

to uncover Amiens and fall back on the Channel ports.

I told him I felt sure there must be some misunderstanding

about this, and that before the general

Conference I thought it was desirable that I should

have a short conversation with the Field-Marshal and

the Army Commanders, whom I had not yet seen.

To this he readily agreed. I accordingly had a little

consultation with Haig, Plumer, Horne and Byng.

They all bore themselves splendidly, showing coolness,

resolution and high courage. I was especially struck

by the attitude of General Byng, who, commanding

the Third Army, had had to bear the greatest and

indeed an almost unendurable strain. As I quite

expected, it turned out that the Field-Marshal’s view

about Amiens had been misunderstood. He had no

doubt in his mind as to the supreme importance of

Amiens, nor any intention of abandoning it. All he

had meant to say was that, as the forces at his disposal,

even after he had skinned the northern part of his

line to the utmost extent, would not enable him to

hold further than to Bray-sur-Somme, he would in

fact be outflanked and unable to cover Amiens, unless

the French came up to his assistance south of the

Somme on the right. Even then it was uncertain

whether, with a big German attack impending against

the Third Army south of Arras, his line would not be

broken, but at any rate he was fully determined to

stand his ground as long as he could, and, with some

assistance from the French on his right flank, he believed

he ought to be able to do so. Byng was also strongly

in favour of the British line making every effort to

stand where it now did, extending to Bray-sur-Somme,

and believed that, though his troops, which had had

tremendous fighting, were very tired, they would not

be beaten. It was evident that everything was being

done by bringing divisions from further north to

strengthen the line between Arras and the Somme.

I next had a few words with the Field-Marshal alone

about Foch, and was delighted to find that, so far

from resenting—as I had been led to believe he might

do—the thought of Foch’s interference, he rather

welcomed the idea of working with the latter, about

whom his tone was altogether friendly.

The views of the British Commanders having thus

been cleared up, the Conference assembled. As on

the day before, M. Poincaré was in the chair. The

others present were Clemenceau, Loucheur, Foch,

Pétain, Haig, Wilson and I. It was at once agreed

that every effort should be made to save Amiens.

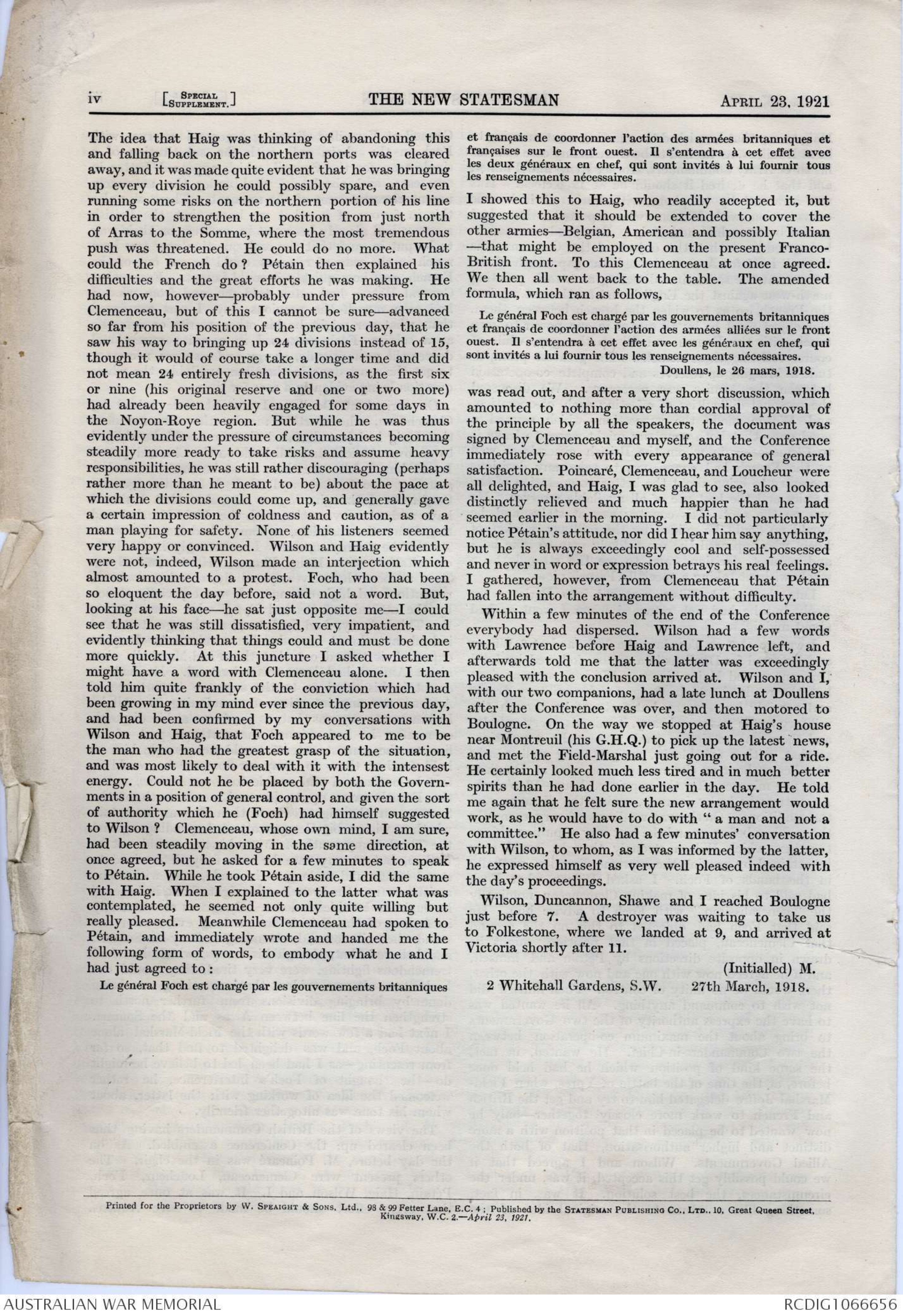

iv [SPECIAL SUPPLEMENT] THE NEW STATESMAN APRIL 23. 1921

The idea that Haig was thinking of abandoning this

and falling back on the northern ports was cleared

away, and it was made quite evident that he was bringing

up every division he could possibly spare, and even

running some risks on the northern portion of his line

in order to strengthen the position from just north

of Arras to the Somme, where the most tremendous

push was threatened. He could do no more. What

could the French do? Pétain then explained his

difficulties and the great efforts he was making. He

had now, however—probably under pressure from

Clemenceau, but of this I cannot be sure—advanced

so far from his position of the previous day, that he

saw his way to bringing up 24 divisions instead of 15,

though it would of course take a longer time and did

not mean 24 entirely fresh divisions, as the first six

or nine (his original reserve and one or two more)

had already been heavily engaged for some days in

the Noyon-Roye region. But while he was thus

evidently under the pressure of circumstances becoming

steadily more ready to take risks and assume heavy

responsibilities, he was still rather discouraging (perhaps

rather more than he meant to be) about the pace at

which the divisions could come up, and generally gave

a certain impression of coldness and caution, as of a

man playing for safety. None of his listeners seemed

very happy or convinced. Wilson and Haig evidently

were not, indeed, Wilson made an interjection which

almost amounted to a protest. Foch, who had been

so eloquent the day before, said not a word. But,

looking at his face—he sat just opposite me—I could

see that he was still dissatisfied, very impatient, and

evidently thinking that things could and must be done

more quickly. At this juncture I asked whether I

might have a word with Clemenceau alone. I then

told him quite frankly of the conviction which had

been growing in my mind ever since the previous day,

and had been confirmed by my conversations with

Wilson and Haig, that Foch appeared to me to be

the man who had the greatest grasp of the situation,

and was most likely to deal with it with the intensest

energy. Could not he be placed by both the Governments

in a position of general control, and given the sort

of authority which he (Foch) had himself suggested

to Wilson ? Clemenceau, whose own mind, I am sure,

had been steadily moving in the same direction, at

once agreed, but he asked for a few minutes to speak

to Pétain. While he took Pétain aside, I did the same

with Haig. When I explained to the latter what was

contemplated, he seemed not only quite willing but

really pleased. Meanwhile Clemenceau had spoken to

Pétain, and immediately wrote and handed me the

following form of words, to embody what he and I

had just agreed to :

Le général Foch est chargé par les gouvernements britanniques

et français de coordonner l’action des armées britanniques et

françaises sur le front ouest. Il s’entendra à cet effet avec

les deux généraux en chef, qui sont invités à lui fournir tous

les renseignements nécessaires.

I showed this to Haig, who readily accepted it, but

suggested that it should be extended to cover the

other armies—Belgian, American and possibly Italian

—that might be employed on the present Franco¬

British front. To this Clemenceau at once agreed.

We then all went back to the table. The amended

formula, which ran as follows,

Le général Foch est chargé par les gouvernements britanniques|

et français de coordonner l’action des armées alliées sur le front

ouest. Il s’entendra à cet effet avec les généraux en chef, qui

sont invités a lui fournir tous les renseignements nécessaires.

Doullens, le 26 mars, 1918.

was read out, and after a very short discussion, which

amounted to nothing more than cordial approval of

the principle by all the speakers, the document was

signed by Clemenceau and myself, and the Conference

immediately rose with every appearance of general

satisfaction. Poincare, Clemenceau, and Loucheur were

all delighted, and Haig, I was glad to see, also looked

distinctly relieved and much happier than he had

seemed earlier in the morning. I did not particularly

notice Pétain’s attitude, nor did I hear him say anything,

but he is always exceedingly cool and self-possessed

and never in word or expression betrays his real feelings.

I gathered, however, from Clemenceau that Pétain

had fallen into the arrangement without difficulty.

Within a few minutes of the end of the Conference

everybody had dispersed. Wilson had a few words

with Lawrence before Haig and Lawrence left, and

afterwards told me that the latter was exceedingly

pleased with the conclusion arrived at. Wilson and I,

with our two companions, had a late lunch at Doullens

after the Conference was over, and then motored to

Boulogne. On the way we stopped at Haig’s house

near Montreuil (his G.H.Q.) to pick up the latest news,

and met the Field-Marshal just going out for a ride.

He certainly looked much less tired and in much better

spirits than he had done earlier in the day. He told

me again that he felt sure the new arrangement would

work, as he would have to do with “a man and not a

committee.” He also had a few minutes' conversation

with Wilson, to whom, as I was informed by the latter,

he expressed himself as very well pleased indeed with

the day’s proceedings.

Wilson, Duncannon, Shawe and I reached Boulogne

just before 7. A destroyer was waiting to take us

to Folkestone, where we landed at 9, and arrived at

Victoria shortly after 11.

(Initialled) M.

2 Whitehall Gardens, S.W. 27th March, 1918.

Printed for the Proprietors by W. SPEAIGHT & SONS. Ltd., 98 & 99 Feter Lane, E.C. 4 ; Published by the STATESMAN PUBLISHING Co., LTD.,10. Great Queen Street,

Kingsway, W.C. 2.—April 23, 1921.

Milne's words re

State of Fifth Army

"The great mystery ws / breakdown o /

Fifth A., wh had not so far been explained.... Broadly

speaking, however, there ws no doubt tt this army

ws shattered"

VOL. X—60

was ordered to work round the left of the enemy so as to

harass the defence, but the main attack was directed against

their right flank. The advance was resumed in this order,

the German prisoner being forced to march in front. Almost

at the outset, however, Bowen was shot by a sniper from

the scrub. Buller rendered first aid, and carried his commanding

officer, who was seriously wounded, into the shade

at the side of the road. Hill took over the command and

continued to attack the trench, making gradual progress.

Meanwhile he sent back Buller to bring up the reinforcements

expected from the Berrima; these Buller met about a mile

back, at noon.

When Elwell commenced his advance from Kabakaul, the

day was windless and hot—so hot that his men on landing

emptied rations, blankets, and clothing out of their haversacks

to lighten the load. As they formed up, Elwell took command

and went on with the right half-company, Gillam following

with the left half in support. Gunner Yeo, to whom Buller

had passed on Bowen’s message for reinforcements, guided

them to the Bitapaka road. About a mile from the shore

they were fired on, either by one of the patrols sent out by

Wuchert earlier in the morning, or by a detachment from

Mayer’s company at Takubar. Elwell, who knew nothing of

the location of Bowen’s party except that it must be fighting

somewhere ahead of him, thereupon decided to send scouts

into the bush on each side, and to proceed quickly with his

main body along the road in fours, since reports were coming

from the connecting files left by Hill that Bowen was hard

pressed. The dust of a long drought was deep under their

feet, and rose in fine clouds, choking their nostrils and filling

their eyes; but the reinforcements pushed eagerly on. Inasmuch

as those who were forcing their way through close,

matted jungle and undergrowth could not keep up with men

advancing on the highway, patrols of six men at a time were

sent along the road ahead of the company; from these fresh

scouts deployed as the others were overtaken, and the men

left behind fell in and formed a rearguard under Signal-

boatswain Hunter.24 The reinforcements had advanced in

24 Lieut. W. D. Hunter; R.A.N. Of Surrey Hills, Vic.; b. Melbourne, 1 Dec.,

1887.

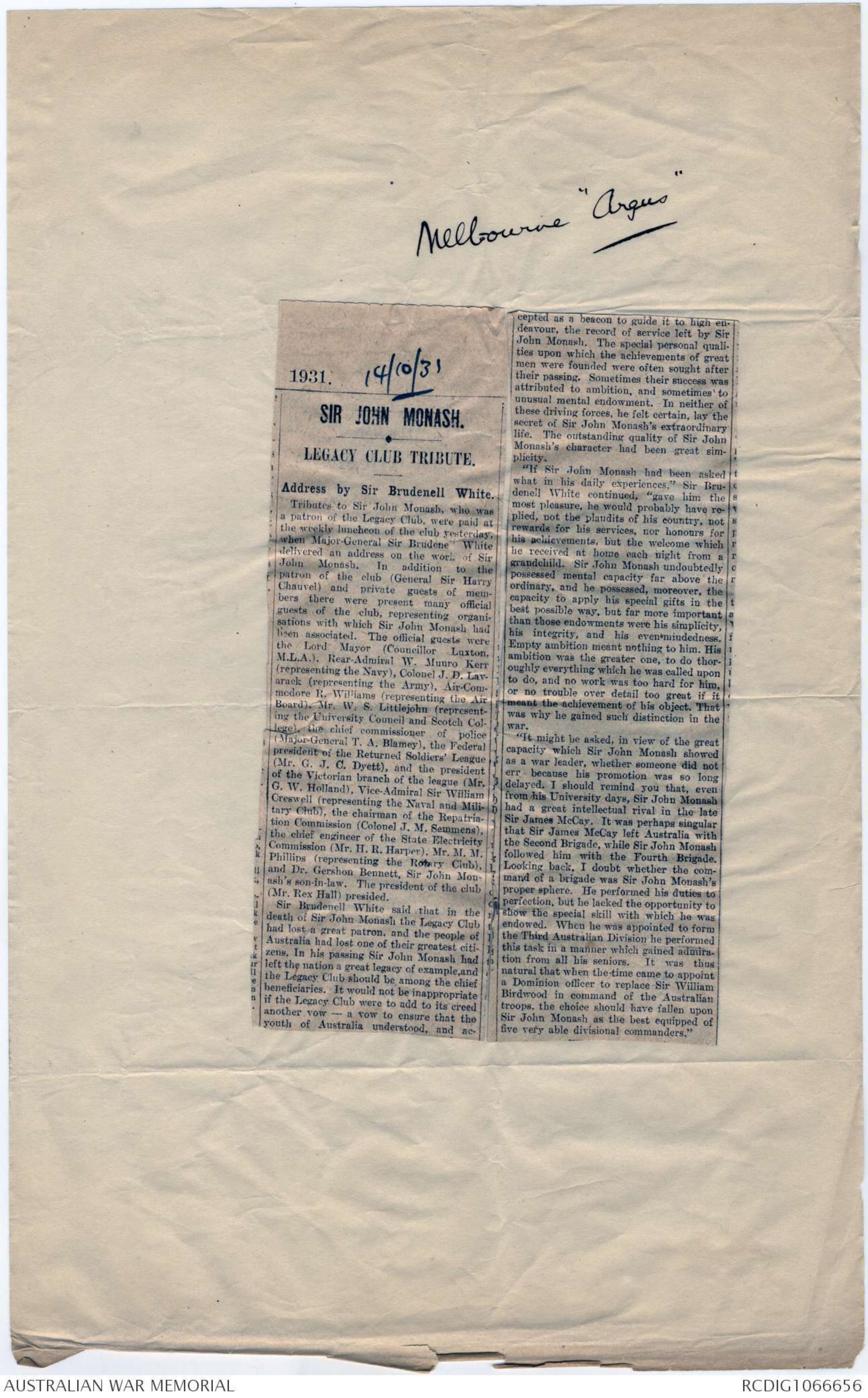

Melbourne "Argus"

1931. 14/10/31

SIR JOHN MONASH

LEGACY CLUB TRIBUTE.

Address by Sir Brundenell White.

Tributes to Sir John Monash, who was

a patron of the Legacy Club, were paid at

the weekly luncheon of the club yesterday,

when Major-General Sir Brundenell White

delivered an address on the work of Sir

John Monash. In addition to the

patron of the club (General Sir Harry

Chauvel) and private guests of members

there were present many official

guests of the club, representing organisations

with which Sir John Monash had

been associated. The official guests were

the Lord Mayor (Councillor Luxton,

M.L.A.). Rear-Admiral W. Munro Kerr

(representing the Navy), Colonel J.D.

Lavarack (representing the Army),

Air-Commodore R. Williams (representing the Air

Board). Mr. W.S. Littlejohn (representing

the University Council) and Scotch College).

the chief commissioner of police

(Major-General T. A. Blamey), the Federal

president of the Returned Soldiers' League

(Mr. G.J.C. Dyett), and the president

of the Victorian branch of the league (Mr.

G.W. Holland), Vice-Admiral Sir William

Creswell (representing the Naval and Military

Club), the chairmen of the Repatriation

Commission (Colonel J.M. Semmens),

the chief engineer of the State Electricity

Commission (Mr. H.R. Harper), Mr. M.M.

Phillips (representing the Rotary Club),

and Dr. Gershon Bennett, Sir John Monash's

son-in-law. The president of the club

(Mr. Rex Hall) presided.

Sir Brudenell White said that in the

death of Sir John Monash the Legacy Club

had left the nation a great legacy of example, and

the Legacy Club should be among the chief

beneficiaries. It would not be inappropriate

if the Legacy Club were to add to its creed

another vow - a vow to ensure that the

youth of Australia understood and accepted

as a beacon to guide it to high endeavour,

the record of service left by Sir

John Monash. The special personal qualities

upon which the achievements of great

men were founded were often sought after

their passing. Sometimes their success was

attributed to ambition, and sometimes' to

unusual mental endowment. In neither of

these driving forces, he felt certain, lay the

secret of Sir John Monash's extraordinary

life. The outstanding quality of Sir John

Monash's character had been great simplicity

"If Sir John Monash had been asked

what in his daily experiences," Sir

Brudenell White continued, “gave him the

most pleasure, he would probably have replied,

not the plaudits of his country, not

rewards for his services, nor honours for

his achievements, but the welcome which

he received at home each night from a

grandchild. Sir John Monash undoubtedly

possessed mental capacity far above the

ordinary, and he possessed, moreover, the

capacity to apply his special gifts in the

best possible way, but far more important

than those endowments were his simplicity,

his integrity, and his even mindedness.

Empty ambition meant nothing to him. His

ambition was the greater one, to do thoroughly

everything which he was called upon

to do, and no work was too hard for him,

or no trouble over detail too great if it

meant the achievement of his object. That

was why he gained such distinction in the

war.

"It might be asked, in view of the great

capacity which Sir John Monash showed

as a war leader, whether someone did not

err- because his promotion was so long

delayed. I should remind you that, even

from his University days, Sir John Monash

had a great intellectual rival in the late

Sir James McCay. It was perhaps singular

that Sir James McCay left Australia with

the Second Brigade, while Sir John Monash

followed him with the Fourth Brigade.

Looking back, I doubt whether the command

of a brigade was Sir John Monash's

proper sphere. He performed his duties to

perfection, but he lacked the opportunity to

show the special skill with which he was

endowed. When he was appointed to form

the Third Australian Division he performed

this task in a manner which gained admiration

from all his seniors. It was thus

natural that when the time came to appoint

a Dominion officer to replace Sir William

Birdwood in command of the Australian

troops, the choice should have fallen upon

Sir John Monash as the best equipped of

five very able divisional commanders."

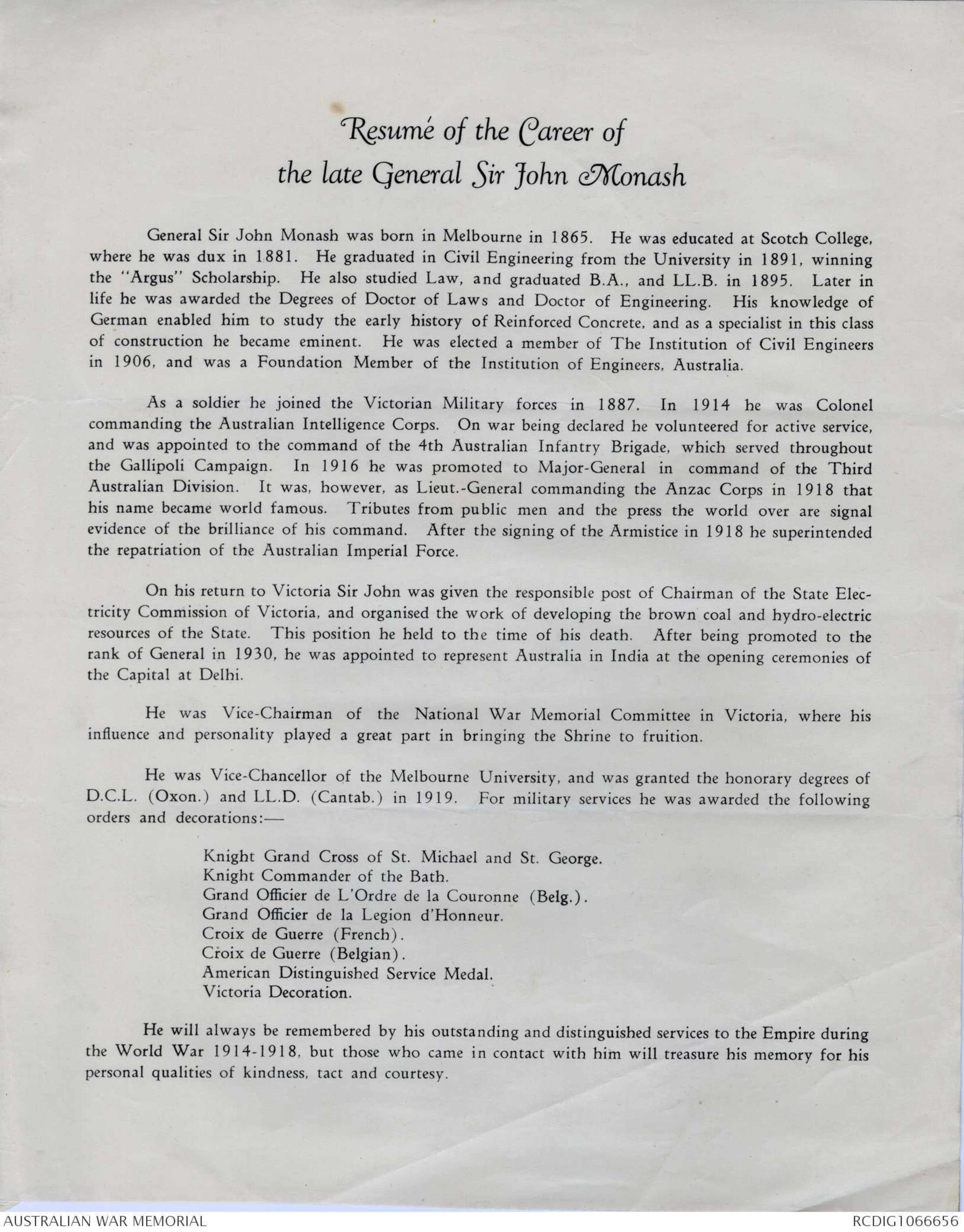

Resumé of the Career of

the late General Sir John Monash

General Sir John Monash was born in Melbourne in 1865. He was educated at Scotch College,

where he was dux in 1881. He graduated in Civil Engineering from the University in 1891, winning

the “Argus” Scholarship. He also studied Law, and graduated B.A., and LL.B. in 1895. Later in

life he was awarded the Degrees of Doctor of Laws and Doctor of Engineering. His knowledge of

German enabled him to study the early history of Reinforced Concrete, and as a specialist in this class

of construction he became eminent. He was elected a member of The Institution of Civil Engineers

in 1906, and was a Foundation Member of the Institution of Engineers, Australia.

As a soldier he joined the Victorian Military forces in 1887. In 1914 he was Colonel

commanding the Australian Intelligence Corps. On war being declared he volunteered for active service,

and was appointed to the command of the 4th Australian Infantry Brigade, which served throughout

the Gallipoli Campaign. In 1916 he was promoted to Major-General in command of the Third

Australian Division. It was, however, as Lieut.-General commanding the Anzac Corps in 1918 that

his name became world famous. Tributes from public men and the press the world over are signal

evidence of the brilliance of his command. After the signing of the Armistice in 1918 he superintended

the repatriation of the Australian Imperial Force.

On his return to Victoria Sir John was given the responsible post of Chairman of the State

Electricity Commission of Victoria, and organised the work of developing the brown coal and hydro-electric

resources of the State. This position he held to the time of his death. After being promoted to the

rank of General in 1930, he was appointed to represent Australia in India at the opening ceremonies of

the Capital at Delhi.

He was Vice-Chairman of the National War Memorial Committee in Victoria, where his

influence and personality played a great part in bringing the Shrine to fruition.

He was Vice-Chancellor of the Melbourne University, and was granted the honorary degrees of

D.C.L. (Oxon.) and LL.D. (Cantab.) in 1919. For military services he was awarded the following

orders and decorations: -

Knight Grand Cross of St. Michael and St. George.

Knight Commander of the Bath.

Grand Officier de L’Ordre de la Couronne (Belg.).

Grand Officier de la Legion d’Honneur.

Croix de Guerre (French)

Croix de Guerre (Belgian)

American Distinguished Service Medal.

Victoria Decoration.

He will always be remembered by his outstanding and distinguished services to the Empire during

the World War 1914-1918, but those who came in contact with him will treasure his memory for his

personal qualities of kindness, tact and courtesy

Sam scott

Sam scottThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.