Charles E W Bean, Diaries, AWM38 3DRL 606/251/1 - 1915 - 1936 - Part 5

Evening Standard 6/4/29

The British Army Saved Us All.

From COLONEL

LIONEL JAMES

C.B.E., D.S.O.

WHAT FOCH TOLD HAIG AFTER

THE ARMISTICE.

To the Editor of the “ Evening Standard."

SIR,—Mr. Robert Duché takes me to task

with regard to the statement made under

my signature in my appreciation of Marshal

Foch in the "Evening Standard” concerning

Petain’s failure to carry out his engagement

to counter-attack the German left flank

with six divisions between the dates of

March 21 and March 26, 1918.

Mr. Duché contends that 42 French divisions

were massed to our assistance between

March 21 and April 3. I do not profess to

know what he means by the expression

“were massed." But the promised counter-

attack by six French divisions in a given

area within a given period did not

materialise, and this failure went within a

hair's breadth of losing the whole war for

the Allies. Good, however, came out of

evil.

This breach of faith on the part of Petain

was the real reason of Foch's appointment

to the Supreme Command

It was not because the British Fifth Army

had failed. It was because the French Chief

Command failed. At British G.H.Q. it was

known that the Germans would attack on the

Somme. It was also known, approximately, in

what strength this attack would be made; it

was just as well known that the Fifth Army, in

face of it, must give ground. Hence the arrangement

with Petain that, when we were forced

back, he should counter-attack the German exposed

flank with the promised six divisions.

Did the French move? Not an inch : not a

man.

Lord Haig saw the impending disaster that

the failure of this guaranteed co-operation implied,

and he sent that famous message to

the British Prime Minister that unless a

Generalissimo were appointed we were about

to lose the war. It was only after Foch assumed

the chief direction that the French were induced

to move from wherever or in what numbers

their divisions “were massed."

These are historical facts, and do not admit

of argument. But as they were at the time

General Staff secrets, their true purport was

not available for publication.

There are other facts concerning the war

which were at the time obscured, but which it

would be well at this moment to place before the

public. At the beginning of August, 1918, the

French Army was almost completely exhausted

as a fighting force. The Americans were a

vigorous rabble. The British Army was the

only force on the Western Front that was a

real fighting instrument. Foch was generous

in his spontaneous praise of Haig's armies. At

the first meeting between Foch and Haig after

the Armistice, Foch's salute was :-

“My dear Marshal, your wonderful army

has saved France, saved all of us; without you

we were beaten."

A few days later when the details were better

known, Foch said at the luncheon table at

British G.H.Q.: —“ The battles of your British

Army will live through all time as classics of

how great military operations should be conducted.

Nothing has ever been seen like them

in the history of all wars !'

Yours, etc., LIONEL JAMES.

AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL RCDIG1066656

237

LORD MILNER AND THE UNIFIED COMMAND.

A Chapter in the History of the Great War.

By W. BASIL WORSFOLD.

. . . . a man prepared to take upon himself responsibility.

(Goschen of Milner.)

THE little town of Doullens lies some 20 miles north of Amiens, whence it can be

reached by two hours of leisurely travel by rail. To all but a very few of even seasoned

visitors to France it remains unknown. And yet it might well have won a place in

the note-books of travellers before the Great War, by reason of the ancient buildings

which recall its long and adventurous history, and the natural beauty of its site.

But whatever caused it to be slighted in the past, to-day all excuse for further neglect

has been removed by the accident which made it the scene of the determining decision

of the War, and thereby of the greatest of the many services rendered by Alfred,

Viscount Milner, to England and the Allied Cause. The true character of this decision

is proclaimed with startling directness on the two unobtrusive tablets affixed to the

iron gates of the Hôtel de Ville : but of Milner’s part in it no hint is given.

The Hôtel de Ville, Doullens.

The contrast between the littleness of the iron tablets and the vast claim of the

twin French and English inscriptions which they bear, is arresting. That on the

right is in French :-

“ Dans cet Hôtel de Ville le 26 Mars 1918 les ALLIÉs ont confié le commandement

unique du Front Occidental au GENERAL FOCH. Cette décision sauva la France et

la liberté du monde."

The English inscription, on the left, reads :-

“ In this town-hall, on the 26th of March, 1918, the ' Allies ' entrusted General

Foch with the supreme command on the Western Front. This decision saved France

and the liberty of the world.

AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL RCDIG1066656

238 LORD MILNER AND THE UNIFIED COMMAND.

It is necessary to have both before us; because the translator of the French

inscription evaded the need of correcting a historically inexact term by quoting

instead of translating the word “Alliés." In point of fact the only government

represented at the Doullens Conference was the French. There were only two

signatures to the document which put Foch then and there in supreme control of

the Allied armies from the North Sea to Switzerland—those of Clemenceau and Milner.

The former as Prime Minister (with the President of the Republic, Poincaré, in the

chair) was fully empowered to act for France. Milner had no specific authority to

represent the British Government. In his assumption of this authority lies the greatness

of his action. Where another man would have referred home for instructions,

and lost what was in all probability the one opportunity of retrieving the disaster of

the German break-through, he took the responsibility of immediately committing

his government, and thereby, within the narrow margin of a few hours, saved the

Allies from incalculable disasters.

How one man’s resolution saved England, the British Empire, and Western

civilization, is the modern story of Doullens. To tell it, we must go back to the closing

months of 1917, and recall both the military situation of the Allies as it had then

developed and Milner’s position in the Lloyd George Coalition Government.

But first, Doullens itself claims a moment’s thought. The Town Hall, which was

the scene of the Conference, was finished only a few years before the War, but the

venerable and historic building whose place it took is also there. This, the Beffroi,

is now dedicated to more humble uses ; but it is there that the past history of the

town centres. Besides its Beffroi Doullens has a vast citadel, built by Vauban to

the order of Louis XIV, and two ancient churches, both of interest. Apart from

the memory of the Conference of 26th March, 1918, Doullens has claims upon the

traveller. In the Great War the town was occupied twice by the Germans, but,

happily, both it and its people

escaped from serious injury.

At Beauvais, south of

Amiens, and known the world

over for the incomparable

Gothic of its unfinished

cathedral and the beauty of

its tapestries, a second inscription

puts on record the

appointment of Foch. It is

engraved on a tablet placed

on the wall to the left of the

principal staircase of the fine

18th century Town Hall:-

"Le 3 avril 1918 Les Représentants

des Gouvernements

Américain, Britannique et

Français, Général Bliss, Mr.

Lloyd George et Mr. Clemenceau,

ont, dans cet Hôtel de

Ville, confié au Général Foch

le commandement suprême

des Armées Alliés.

A cette réunion assistaient

The Hôtel de Ville, Beauvais.

AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL RCDIG1066656

LORD MILNER AND THE UNIFIED COMMAND. 239

les commandants en chef des Armées, Général J. Pershing, Maréchal Sir D. Haig

et le Général Pétain ainsi que le Lieutenant Général Sir H. Wilson, chef d’ état-major

général Impérial de l’ armée Britannique, le Général Mordacq, chef de cabinet

militaire du Président du Conseil Français, Ministre de la guerre, et le Général

Weygand, chef d’ état-major du Général Foch.

PART I.—THE PROBLEM.

In a cartoon in Punch of 13th March, 1918, TOMMY (off to the Front) says to a

shipyard hand, “ Well, so long, mate ; we’ll win the war all right, if you’ll see that

we don’t lose it.”. And, in speaking, he points to a poster on which is printed : “The

only thing that can rob us of VICTORY is a shortage of ships.” The date was eight

days before the German offensive began (21st March), and the cartoon, no doubt,

faithfully reflected the belief of the great majority of the British people at the time in

question. The War Cabinet and the War Office knew that the issue was not quite

so simple ; but their anxieties were hidden successfully from the Press and the public.

The position of the Allies on the Western Front at the beginning of 1918 was this.

It was known, of course, that the Germans, heavily reinforced by the troops released

from the Eastern Front by the collapse of Russia, were about to launch a great

offensive, but precisely where, and when, the thrust of the spear-head would point

could not be determined with equal certainty. For the first time since the combatant

armies on this front had settled down into trench-warfare there was a numerical

preponderance on the German side ; and the only source—short of abandoning the

campaigns of Salonika and Palestine—from which the adverse balance could be

redressed was America. From its entry into the War in April of the preceding year

the United States had set to work to build up from its civilian population a great

army for service in Europe. But the process was necessarily lengthy, and although

by that time many thousands of Americans had come to France for their final training

and equipment, when the German offensive actually began there were only three

divisions of American troops, with not a single aeroplane, in the fighting line.

In the face of the threatened offensive the French and British Governments and

military staffs had not been idle. The disaster of Caporetto had enforced the recognized

need for the concerted direction and control of the Allied armies operating against

the Central Powers from the North Sea to the Balkans*; and at the Rapallo Conference

(9th November, 1917), a Supreme War Council (Conseil supérieur de guerre)

had been constituted† for the purpose. The Council itself was composed of the Prime

Ministers and one other representative of the several Allied Governments directly

concerned ; and there was attached to it a body of technical advisers, consisting of

military representatives of the respective governments, which was to be in continuous

session at Versailles. Thus from the end of November, 1917, a common military

advisory body, composed of General Foch‡ (France), Sir Henry Wilson (England),

General Cadorna (Italy), and General Bliss (U.S.A.) had been installed; and this

body had applied itself to the problem of unity of command. In the meantime the

Commanders-in-Chief and General Staffs of each Power remained, as before, separately

responsible to their respective governments.

* Since the summer of 1917 Mr. Lloyd George had been seeking a means of establishing the unified command

on the Western Front, and a Cabinet Committee, set up for the purpose, had noted the significance in this connection

of the relative failure of the separate British advance in Flanders with the heavy losses of Pachendaelle. More than

this, it had been recognized that if, as seemed inevitable, the holder of the unified command must be a Frenchman,

the British Government must claim the right to select this Frenchman, in order that he might be a soldier acceptable

to the British Army and its commanders.

† More accurately, the Council was constituted in theory at Rapallo. Nobody did anything until Sir Henry

Wilson went over to Paris later in November, and by his own determination brought the decision into operation.

Then a (second) session of the Council was held at Versailles on 1st December, 1917.

‡ Theoretically again, Foch was not on the military staff of Versailles, because it was not composed of Chiefs

of Staff. But General Weygand (who was) was so intimately associated with Foch that it came to the same thing

AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL TCDIG1066656

240 LORD MILNER AND THE UNIFIED COMMAND.

On 30th January, 1918, the Supreme War Council again met at Versailles. At the

end of four days’ deliberations it had worked up to a decision, which, while not providing

a unified command of the Armies in the field, did provide—what was next in

importance to it—a unified control of the reserves. The authority set up to give

effect to this decision was a Committee, of which Foch had been unanimously appointed

President. Its duties were (1) after consultation with the several Commanders-in-

Chief to form a general reserve available for reinforcing the French, Italian, or Balkan

Fronts ; and (2) to allocate the stations, and control the movements, of the divisions

comprising it. For these purposes the several Commanders-in-Chief were to be

required to put certain of their reserves under the control of the Committee, but any

of the divisions thus detached were, on entering the fighting line, to pass back to

the control of the Commander-in-Chief to whom they might be assigned.

This advance on the path of unity, achieved at the Versailles meeting, was due

mainly to Sir Henry Wilson, who, as the organization of the Council proceeded, had

changed his style from “ British Military Adviser to the Supreme War Council,” to

“Permanent Military Representative, British Section, Supreme Council.” In the

course of the proceedings he showed that the Allied line could be held against the

Germans, provided that the French and British reserves were treated as one. His

contention was demonstrated to the British delegates by Kriegspiel and in two

lectures, illustrated with diagrams,* all of which greatly impressed Mr. Lloyd George.

For reasons which he gave, the spear-head of the German offensive must be directed

against one of two points. If the British were to be attacked, the thrust would come

at a point on the Somme Front ; if the French, at a point on the Champagne Front.

In the event the calculations made by him and the British staff at Versailles proved

to be astonishingly accurate.† Wilson’s forecast of the divisions which Ludendorf

could concentrate, was within one of the number—nearly a hundred—actually

launched, and the place he predicted was within a mile of the point on the Somme

Front at which the German spear-head was, in fact, thrust. The date, however,

which he assigned for the offensive was considerably later than that at which it actually

took place. In this respect the forecast of the British Headquarters Staff at Montreuil

was the more accurate : since on 18th March—three days before the offensive began-

the Director of Military Intelligence thought it certain that the attack would come

before the end of the month.

It is a melancholy and disquieting fact that the advance towards unity of command,

thus achieved mainly through one British soldier, Sir H. Wilson, was destined to be

frustrated—again mainly and on perfectly intelligible, if not equally valid, grounds -

by another British soldier, and this the British Commander-in-Chief, Sir Douglas

Haig. Nor was Haig alone in his opposition to the Versailles plan. On 18th February,

largely as a protest against an arrangement which did not give him a voice in the

control of the reserves, Sir W. R. Robertson resigned his position as Chief of the

Imperial General Staff. On the following day Mr. Lloyd George appointed Sir H.

Wilson to succeed him. At the same time General (now Lord) Rawlinson took

Wilson’s place as the British Permanent Military Representative at Versailles.

The British forces held 125 miles of hotly engaged front, and in Haig’s opinion

they were barely sufficient in numbers adequately to defend it. On his return from

the Versailles meeting of the Supreme Council he decided that to detach six or seven

divisions from these inadequate forces, and hand them over to the Foch Committee,

would not be consistent with his responsibility for the British Front. From the first

* The problem was stated in one from the German point of view by Sir H. Wake and in the other from the

Allied, by General Studd.

† So also were those of the G.H.Q., near Montreuil, where Gen. Sir Herbert Lawrence was Haig's Chief of Staff.

AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL RCDIG1066656

LORD MILNER AND THE UNIFIED COMMAND. 241

he made no secret of his inability to contribute to the general reserve, but he did not

refuse officially to comply with the requirements of the Foch Committee until the end

of February.*

During the weeks that Haig was in this mind, Pétain, the French Commander-in-

Chief, while professing to carry out the decision of the Supreme Council, did nothing.

At the same time he suggested to Clemenceau—the French Prime Minister—with

whom naturally he had much influence, that the whole scheme was impracticable,

More than this, Pétain expressed the same views to Haig; and the two came to an

understanding. They agreed that they could, and would, support each other in an

emergency, and that this arrangement was much better than the Versailles scheme,

under which they would be subject to the interference of Foch and his committee.

On the 14th and 15th March the Supreme Council met in London. Haig’s attitude

towards the Foch Committee had been viewed with anxiety by the War Cabinet,

and the question of enforcing the authority of the Council, with a resultant change in

the British command, had not been overlooked. At the same time the Cabinet had

received the disturbing intelligence that under Pétain’s influence M. Clemenceau, the

French Prime Minister† and Minister for War, was withdrawing his support from the

plan of a general reserve under the control of the Foch Committee. In these circum-

stances the British War Cabinet and their military adviser, Sir Henry Wilson, awaited

the meeting of the Supreme War Council with grave concern ; and from the account

of it given in Wilson’s diary we learn how completely these apprehensions were

justified.‡ On 13th March, Milner, Wilson and Amery met and agreed that if Lloyd

George, who was to see Haig at 10 a.m. on the following morning, “ could not persuade

Douglas Haig to contribute divisions to the General Reserve,” then “the General

Reserve and the Executive Board ought for the present to remain in abeyance.Ӥ

On the 14th (Lloyd George having failed meanwhile to persuade Haig) the Supreme

Council met at 11.30 a.m. at 10, Downing Street. “ Two hours talk of General Reserve,

and no decision. Then adjournment for lunch,” Wilson wrote. It was revealed,

however, not only that Haig (who was there) and Pétain (who was in France) were in

complete agreement in holding that everything necessary to counter the German

offensive could be done by mutual arrangement between themselves, and the Versailles

plan unnecessary, but that Clemenceau supported Pétain and the Haig-Pétain understanding.

To meet this situation the British representatives, seeing that it was hopeless in

the face of Clemenceau’s support of the two Commanders-in-Chief to attempt to enforce

the authority of the Foch Committee, brought forward in the afternoon session a

resolution embodying the conclusion reached by Milner, Wilson and Amery on the

preceding day. “I lunched with Lloyd George and Hankey (Wilson continued), and,

at lunch we drafted a resolution, afterwards adopted, to the effect that, to begin with

no divisions in France should be put in the General Reserve, but our five and the

French six with a quota of Italians, all in Italy, should form the nucleus. Of course,

in a sense this is nonsense, as it does not give us any General Reserve ; but it does

keep the main idea alive and it does save the position of the Executive Board. So

* The account given in “ Sir Douglas Haig’s Command ” (by G. A. B. Dewar and Lt.-Col. J. K. Boraston, 1922,

Vol. II, page 56), of Haig’s action and its effects is perfectly frank. “ Could he feel confidence that such a committee

would act and act quickly, its French and British and Italian and American members at complete accord, on an

emergency ? He could not, so he was unable to contribute to this general reserve. As a result, the proposal

perished.“ The “ proposal,” be it remembered, was the plan by which the Supreme War Council of the Allies

proposed to counter the German offensive.

† I.e., President of the Council of Ministers.

‡ “ Field-Marshal Sir Henry Wilson, Bart., G.C.B., D.S.O., His Life and Letters.” By Major-General Sir C. E.

Callwell, 2 vols., Cassell, 1927.

§ Vol. 2, page 69.

AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL RCDIG1066656

242 LORD MILNER AND THE UNIFIED COMMAND.

that on the whole I think it is our best course. Foch protested against this arrangement,

but Clemenceau accepted it in the name of France."*

By this misbegotten resolution the opposition of Haig and Pétain was condoned,

and the Foch Committee deprived of all authority to act in France: that is, to create

and control the common reserve which Wilson and Foch held, and the British War

Cabinet believed, to be the sole means by which the impending German offensive

could be countered with success. Thus, within a week of the German offensive the

Supreme War Council of the Allies had dissolved in impotency.

Here it must be noted that the attribution of the main responsibility for this

deplorable result to Clemenceau’s change of front on the general reserve question has

been challenged by Marshal Foch. With reference to an article on the Doullens

Conference published in The Times of 26th March, 1926, in which I had advanced the

same view of M. Clemenceau’s attitude at the London meeting of the Supreme Council

Marshal Foch was reported by The Times Paris correspondent (30th March, 1926) to

have said : “ Marshal Pétain was not there, and it was not M. Clemenceau who

supported him, but the British Government. 'M. Clemenceau,’ said Marshal Foch,

'simply accepted the British position.’” As the resolution in question was drafted

and moved by the British representation, and only accepted by Clemenceau on behalf

of the French Government, the official record of the proceedings of the London meeting

of the Supreme Council (if, and when, made public) would probably support Marshal

Foch in his contention. Whereas in fact it was Clemenceau’s support of Pétain as

against Foch, coming on the top of Haig’s refusal to part with any of his divisions,

that led the British representation to move the resolution as a device for saving something out of the wreck of the Versailles plan of a unified reserve. Foch, who was

present, was, naturally, deeply chagrined; but, when on the following day he presented

a full and reasoned statement of his objections to the resolution, in which, as he asserted,

the Supreme Council had reversed its own previous decision and thereby stultified

itself, his protest was merely recorded and the discussion was not re-opened.

Returned to Paris, Foch, like Achilles, nursed his wrongs in moody silence.

Clemenceau ceased to consult him. While remaining Chief of the French General

Staff, and not removed officially from his presidency of what was intended to be the

strategic executive of the defence, the foremost soldier of France in this all-important

issue counted for nothing when Ludendorf launched his concentrated legions against

the Allied lines.†

On this side the Channel, the British Government remained in its inconclusive

conclusion that, in view of the imminence of the German offensive it could not insist

upon the enforcement of the Versailles plan, since such action might, and probably

would, involve a change in the British Command.

When—on 21st March—the German offensive came, and the British line was

shattered where it joined the French, what Foch had told the Supreme Council at the

London meeting would happen, did happen. The alternative plan, the understanding

between Haig and Pétain, broke down. Pétain for two and a half days refused to

believe that the attack on the Somme Front was the real thrust of the German spear-

head. The great attack, he was convinced, was to come on the French Front in

Champagne. Therefore, he would not move his reserves—except three very inferior

divisions from the Vosges. And in the event the Germans reached the detraining

stations of these three divisions before the divisions.

* Ibid., page 70.

† Marshal Foch at that moment had been practically eliminated from the direction of military affairs, in

consequence of his disagreement with M. Clemenceau at the London meeting of the Supreme Council just before."

L.S.A. (Mr. Amery) in The Times of May 16th, 1925. And Mr. Amery, be it remembered, was liaison officer between

the permanent staff of the Supreme War Council at Versailles and the British War Cabinet in London.

AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL RCDIG1066656

[[bas?]] Petains order to retire [[?]] at 1

[[Suffer?]] of his foot.?

AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL RCDIG1066656

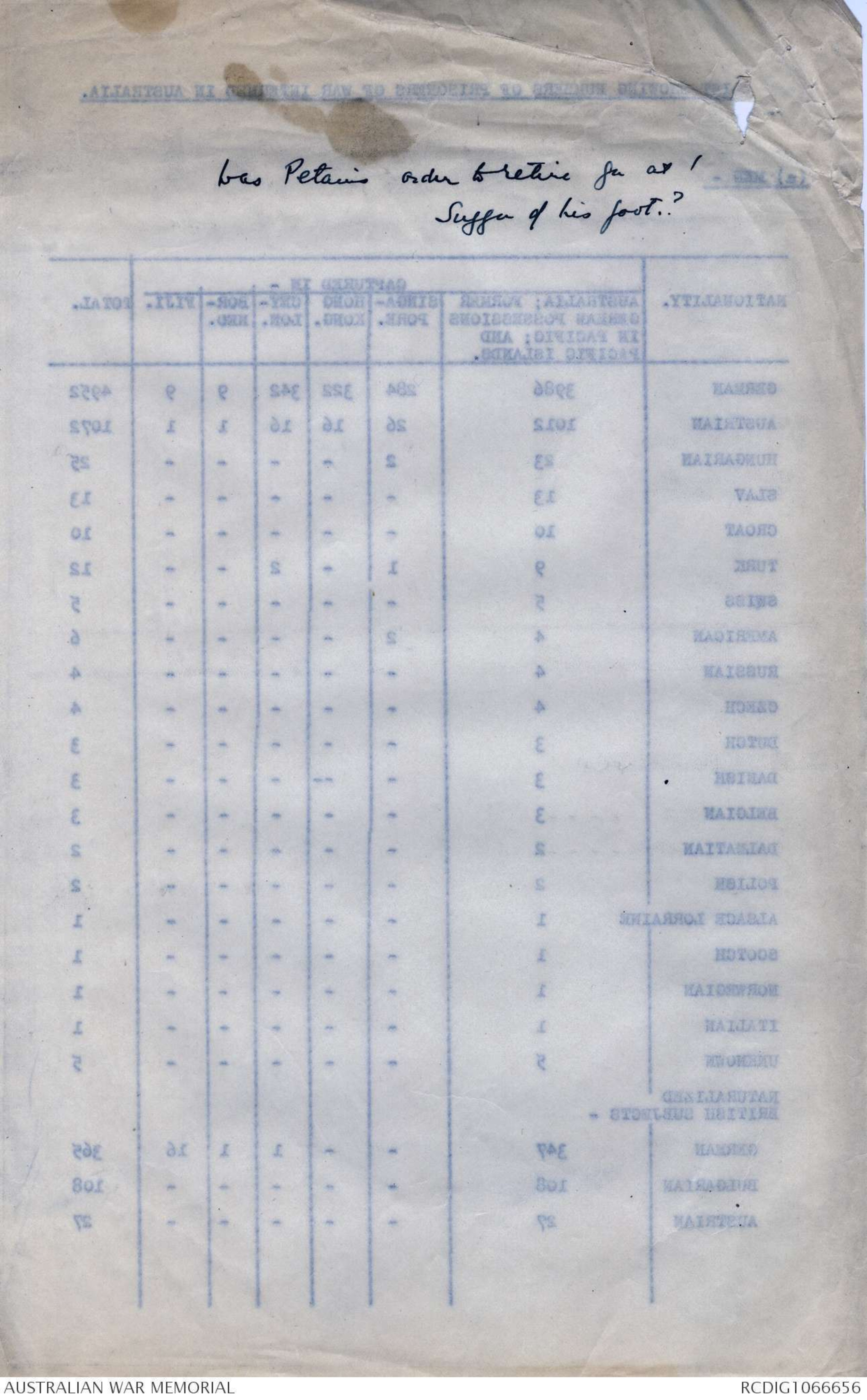

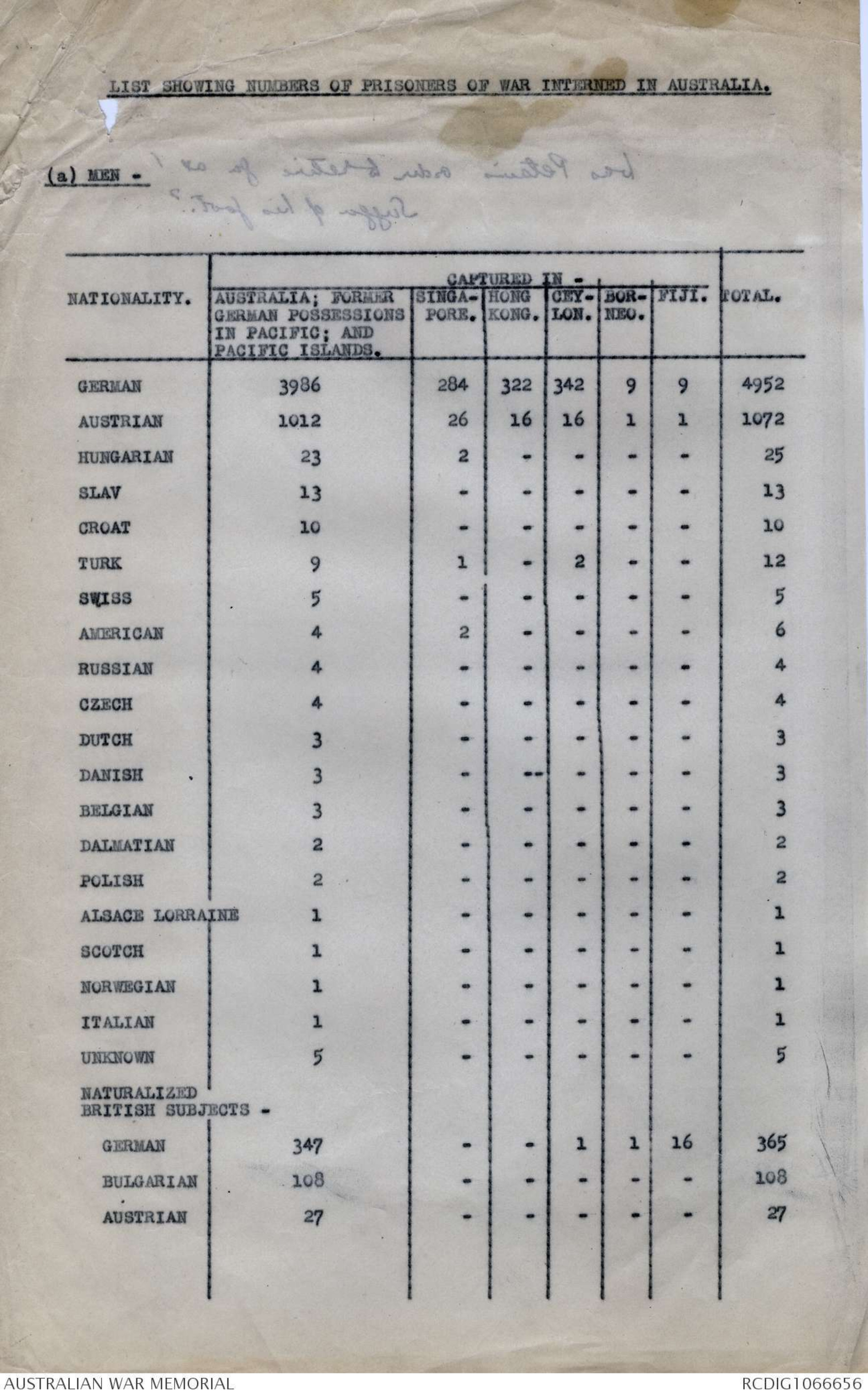

LIST SHOWING NUMBERS OF PRISONERS OF WAR INTERNED IN AUSTRALIA.

(a) MEN -

| NATIONALITY | CAPTURED IN - | ||||||

|

AUSTRALIA; FORMER GERMAN POSSESSIONS IN PACIFIC; AND PACIFIC ISLANDS. |

SINGA- PORE. |

HONG KONG. |

CEY- LON. |

BOR- NEO. |

FIJI. | TOTAL. | |

| GERMAN | 3986 | 284 | 322 | 342 | 9 | 9 | 4952 |

| AUSTRIAN | 1012 | 26 | 16 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 1072 |

| HUNGARIAN | 23 | 2 | - | - | - | - | 25 |

| SLAZ | 13 | - | - | - | - | - | 13 |

| CROAT | 10 | - | - | - | - | - | 10 |

| TURK | 9 | 1 | - | 2 | - | - | 12 |

| SWISS | 5 | - | - | - | - | - | 5 |

| AMERICAN | 4 | 2 | - | - | - | - | 9 |

| RUSSIAN | 4 | - | - | - | - | - | 4 |

| CZECH | 4 | - | - | - | - | - | 4 |

| DUTCH | 3 | - | - | - | - | - | 3 |

| DANISH | 3 | - | -- | - | - | - | 3 |

| BELGIAN | 3 | - | - | - | - | - | 3 |

| DALMATIAN | 2 | - | - | - | - | - | 2 |

| POLISH | 2 | - | - | - | - | - | 2 |

| ALSACE LORRAINE | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| SCOTCH | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| NORWEGIAN | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| ITALIAN | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| UNKNOWN | 5 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

|

NATURALIZED BRITISH SUBJECTS - |

|||||||

| GERMAN | 347 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 16 | 365 |

| BULGARIAN | 108 | - | - | - | - | - | 108 |

| AUSTRIAN | 27 | - | - | - | - | - | 27 |

AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL RCDIG1066656

LORD MILNER AND THE UNIFIED COMMAND. 243

This was the monstrous tangle that Milner, suddenly, unexpectedly, and with no

specific instructions to guide him, was sent to France to unravel. He did unravel it.

When Pétain and Haig, each with a scrupulous regard to his own separate responsibilities, as nearly as possible lost the War, Milner saved it.

To understand his doings during his three days in France (24th-26th March),

something must be said of his position in the Lloyd George Coalition Government,

which had been formed in December, 1916, and was then in office. Milner was a

member of the War Cabinet of Six, and for various reasons he, more perhaps than any

other member of this virtual directorate of the British Empire, had been drawn into

close contact with those soldiers and others who were especially concerned with the

need for a better organization of the Allied forces and with the creation of the Supreme

Council and its staff at Versailles. Of these, three in particular were intimate friends

and associates ; Sir Henry Wilson, since 19th February, Chief of the Imperial General

Staff; Sir Maurice Hankey, the Secretary of the War Cabinet; and Mr. (Lt.-Col.)

Amery, Assistant-Secretary of the War Cabinet. The last, after the Supreme War

Council had been constituted in the previous November (1917), had been placed on

the personal staff of the Secretary for War, and on the permanent staff of the

Supreme Council at Versailles* to act as a liaison between that body and the War

Cabinet. To this must be added the circumstances that, directly after the outbreak

of the War, Milner had handed over his country house, Sturry Court, near Canterbury,

to the military authorities ; and that later in the same year (1914) he had moved from

the chambers at 47, Duke Street, St. James’, which for so many years had been his

London home,† to 17, Great College Street—a house under the shadow of Westminster

Abbey, within a stone’s throw from Downing Street and Whitehall.

Disquieting accounts of the German attack on the British Front, which was launched

at 4.30 a.m. on Thursday, 21st March (1918), reached the Cabinet the same day ;

and still graver news followed on Friday. On Saturday, Milner was sixty-four;

but on this 23rd of March he had scanty opportunities for birthday memories.

First, his (official) secretary came from the War Cabinet offices in Whitehall Gardens

with an ominous telegram from the Front, and warned him to be ready for an emergency Cabinet. Then, either at Whitehall Gardens or at Great College Street, he was

rung up” from Versailles by Mr. Amery. (The French were badly “rattled ”:

could he come over ?) After lunch he was called to 10, Downing Street, where he

took part in an anxious discussion of the situation with the Prime Minister, Bonar

Law, Sir Henry Wilson, Churchill and Smuts.‡ From Downing Street he crossed to

the War Office with Wilson ; and there from 5 to 6.30 the War Cabinet met. When

the Cabinet was over Mr. Lloyd George left London for his house at Walton Heath,

and Milner returned to Great College Street. Here, “ after a late tea,” he was rung

up by the Prime Minister at Walton Heath. (Someone must go over, and find out

what the position was. Would he go to Versailles to-morrow ?) Milner at once

agreed to go. He dined alone at Brooks’; and on his return to Great College Street

heard the latest news from the Front by ’phone from Wilson. As Minister without

portfolio, he was deeply engaged in the special work of the War Cabinet, and the

re-arrangements which this sudden absence required kept him up until 2 o’clock

(Summer-time, which came into force that morning).

The 24th was Palm Sunday. In London the joyous associations of the day were

lost in the gloom of a military disaster, as overwhelming as it was unexpected and,

* Since the War Mr. Amery has been successively Under-Secretary for the Colonies, First Lord of the Admiralty,

and (as now) Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs and for the Colonies.

† He took his title (in part) from them—Milner of St. James' and Cape Town.

‡ For the measures immediately taken by Wilson and the Cabinet to meet the military crisis, see “ Sir Henry

Wilson, &c.," ii, page 74.

C

AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL RCDIG1066656

Diane Ware

Diane WareThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.