Charles E W Bean, Diaries, AWM38 3DRL 606/251/1 - 1915 - 1936 - Part 4

Soldiers & Statesmen

Robertson Vol I 270-271

1 Franco- Brit. Offve not definitely appd by

Cabinet until after March 27 (Confce in Paris)

In spite of Cabinet being warned tt object

of Somme was (1) Repel of Verdun (2) Inflicting of

heavy losses on German arms - it was

abt July 29 showing sensitiveness at

the loss (wh ws wrongly calculated by

Haig i.e. excess over normal).

They asked R whether he thought a

loss of, say, 300,00 men "wd "lead to really

great results, because if not we

ought to be content w something less than

what we are now doing".

Asked why Fr weren't fighting

B Fr were asking why we weren't fighting

V1 army (report on its morale by Brit

staff)

L.George ws never whole-hearted on the W Front

but had to be silenced by R's assurances-

He wd accept them

Aug 29 They approve of the go slow and get ready policy

(27 June)

Aug . Rumania joins - L.G. wants to expand

campaign in Macedonia.

France wants it: Brit Div from Fr & some

tps from eg (40 000) in all) sent.

Nov. location but Somme to close: All 3 objects attained.

[* 49476*]

Third wk end∧of Nov. 1916 L.G. asks Rob. whether we may expect

to win the war by a knock out blow - if

not the advisability of contuing war to the bitter

end wd call for reconsidern.

R. Thinking a party in / Cab. might be wanting

to consider an early peace by negotiation

hit straight out - & sd - if measures were

taken "I am satisfied that the K.O. blow can

& will be delivered".

At the end of the year Asquith ministry fell -

"Throughout 1916 the General Staff were

accorded suitable freedom of action" (286)

R. ws of opinion tt G Brit gave way to her

allies too much (r 8 7)

Man Power.

Jan 1916. All single men & widowers of ^ages between 18-41 to attest.

after a specified date if not volunteering before (293)

(in consequence of Derby pledge - all single

men had to go before the married)

[In Sum] ? May 1916 Military Service Act incld

married men. (Not Ireland).

Aug 1916 man-power distribution board

to supply labour for essential industries - but cdnt

for Depts. to agree.

[*IV / *] June 1916 L.G. min for War. (307) Dec.1916 P.M,

But94 he failed to increase man-pow supply of men

as desired by R. L.G. held tt Labour wdnt

stand any more

compulsion

Robertson

Man Power

p. 308. In winter 1916-17 R thought Gy wd make her

[*VOL IV*] maximum effort in summer 1917.

R had to tell Cabinet in Feb tt army cdnt

be kept up to strength during 1917. now too

late for

measures

Cabinet asks Army Council to

consider reducing bns per divn from 12 to 9.

Gy had made the change & Fr.

(309).

Measures of 1916 brought strength of army to climax

in 1917. Thereafter it declined.

24 Nov 1917 C in C infs. Army Council tt he wd

be 250,000 short in infy by end of Mar 1918.

Haig, present in War Cab. on Jan 7 1918,

makes a statement wh leaves in W. Cab. the

impression tt Gs won't att. on W. Front. that

[*Vol V*] Rob. & Derby both think this will be effect on

W. Cab. Haig doesn't. (Haig ws inarticulate

& possibly nervous - Curzon asked him qns

designed to give him a chance of bringing out

his need for men - & he had assured W. Cab

tt if Gs were wise they wdnt att. A subsequent

letter from Haig ws tossed aside by P.M. at ^ later W. Cab

as being inconsistent w his verbal statement). (324)

R. asks PM for early emplt of Americans arrvng

Brit.

Forecast of Americans (328)

SM Herald 21/3/1928

THE GERMAN ATTACK

Great Drama of 1918.

FIFTH ARMY'S ORDEAL.

(BY F. M. OUTLACK.)

Ten years ago to-day began the great German

offensive in France—Ludendorf's gambler's

throw. Those times seem very far

off; yet it is safe to say that, in city and

country, thousands of Australians will recall

without reminder the war-time crisis of which

to-day is an anniversary, and probably will

debate the old question of the moral of the

Fifth Army. The debate lives, though the

real question has long been settled. The truth

is that the Fifth Army, overwhelmingly

out-numbered, with no supports, and reeling under

the heaviest attack the Germany Army could

deliver, fought one of the bravest soldiers'

Battles in the record of the British Army.

It requires no effort of the imagination

in anyone who survives those great days on

the Western Front to live again the intensity

of the drama which opened on the 21st

of March. The German Army, heavily punished

in the preceding year by one offensive,

after another along the whole British front,

was, early in 1918, reinforced by a great

strength of fresh divisions brought back from

Russia, where the revolution had broken down

opposition. By February a grand enemy attack

was known to be imminent. The Australian

Corps was in Flanders on the Messines

Ridge and Hill 60, confident for a time

that the assault would come upon that

northern portion of the British lines. The central

bastion, the Arras position, was held by the

British Third Army. To the south of it lay the

Fifth Army, weakest of all on its extended

line. When surmise of the German plans

in the Cambrai-St. Quentin sector settled

into a certainty—as evidence grew

pointing to that locality as the chief

scene of enormous German labour in

mounting battle preliminaries—the strain

became painful. Everything that could be done

was done in the organisation of depth in

defence. This was the rule along the whole

British line. As each new morning dawned

in March there was only one question on

everybody's lips: Has it come yet?

THE AUSTRALIANS.

While many training divisions were held

in England, the bulk of the British force in

the field lay in the north and about Arras.

For days before March 21, every Australian

soldier could have told you that orders were

ready for a march south to the Somme again.

No division in the army would escape the

fight that was coming. The period of waiting

became almost intolerable. When the first

news came on the great day, the half of

the Australian Corps in the line at Messines

itched to be relieved. The other half, at

rest behind the lines, was already packing

up. Some officers went and packed as soon

as they read the first news bulletin. Divisional

staffs began cornering lorries. They knew

what the coming orders would be as well as

if they had written them themselves. And

none who lived through that electric time

will ever forget the high enthusiasm of the

Australian march south by rail and road and

on foot, or the singing Digger columns, decked

with dust, and answering cheer for cheer

with the inhabitants of a dozen familiar

French villages on the old rolling down

country of the Somme, known to them like

home. To those veteran battalions, made

veterans in this place, the very sight of the

landscape sent their moral soaring; and the

villagers’ cries of Vive les Australians!

fired the spirits of the weariest. The arrival

in advance of the 4th and 3rd Australian

Divisions in the farmlands behind Herbuterne

and Albert seemed less the approach of

reinforcements into a doubtful battle than a

triumph after great victory. French civilians

preparing to move, unloaded their carts and

stayed. "Fight the Boche, Madame?" said

one Australian officer. We are going to

eat him!"

THE FIFTH ARMY'S TASK.

The diggers’ indomitable confidence was

borne out in many a stiff fight thereafter,

but at the time it led to occasional reflections

upon the fight of the Fifth Army during the

five or six days before the Australians arrived

on the scene. Because here and there some

of that prejudice lingers, it is only right to

say that the first hasty judgment was cruelly

unjust to a number of heroic British divisions,

and a South African brigade, that fought to

the limit of human endeavour. Under the

blow they sustained the thinly-held front at

Cambrai and St. Quentin had eventually either

to break or to bend. Some stigma was attached

to General Gough, who commanded

the Fifth Army; but his dispositions and

his directions in that week of fate have been

since weighed in the balance and found not

wanting, and what judgment of the army he

suffered was based chiefly upon earlier criticism

of his conduct of operations in the Ypres

salient of 1917. The acid question to be put

to Australian critics of the Fifth Army in

March, 1918 is —'"What would the Australian

Corps have done if it had had to hold that

St. Quentin sector as the British had to

hold it?"

The Fifth Army's defence has been contrasted

with that of Byng's Third Army at

Arras, which on March 28 and 29 withstood

the shock of a full-dress German assault of

great ferocity and budged not an inch. Yet

here-again criticism falls before the facts.

On March 21 the Fifth Army, holding 41

miles of front with only 14 infantry divisions

and 3 cavalry divisions (which together about

equalled another division of infantry), had to

meet the onslaught of 46 massed German

divisions. The Third Army on March 28 held

26 miles of front with 19 divisions. and was

opposed by 24 enemy divisions. Gough held

a front more than half as long again as

Byng's, and was outnumbered more than three

to one by an enemy confident of success. Byng

was attacked by a force only a little greater

than his own, and by an enemy already aware

that his blow was being parried.

WHY NO RESERVES?

Why was the Fifth Army left without help

for so long, without reserves? Why, when

the place and finally the date of the attack

had been read by Intelligence with complete

accuracy, was there no arrangement for

supporting the weak defending force against

repeated blows? Was the Fifth Army meant

to be sacrificed?. These questions, bewildering

at the time, or immediately after the German

blow had spent itself, have been answered

since. Colonel Boraston, of British G.H.Q.,

has written (Ninteenth Century, October.

1920):_

The British Commander-in-Chief and his General

Staff had formed the opinion that the most likely

front against which the blow would be directed was

the point of Junction of the French and British

armies, and with this conviction uppermost in his

mind the Commander-in-Chief paid more than one

visit to the French Grand Quartier General at

Compeigne during the winter months of 1917-18..

It can hardly be suggested, then, that the attack

was not expected by the British, or that its front

was not known with a very considerable degree of

accuracy....The discussions with the French had

led to definite arrangements for mutual assistance in

the case of attack. These arrangements provided

specifically for the action to be taken by the French

in the event of an attack such as that which was

actually delivered on the British on March 2l. Plans

for mutual assistance between Allied commanders may

be excellent, but it is their execution at the right

moment that always presents the real difficulty. If

the French command could have been convinced a

the accuracy of the British forecast of events,

detachment of six French divisions should have been

ready on March 21 to take over instantly the right

wing of the British army. The warning had been

ample. Had these divisions been there, or even

in the neighbourhood, there would have been every

chance that with their help the Fifth Army front

would have sustained the German attack as

successfully as did that of the Third Army.

Unfortunately the French Higher Command were

persuaded that a great attack was imminent on the

Laon-Rheims front, and that the anticipated assault

upon the British, If it took place, would prove to be

a diversion. They persisted in this belief even

after the attack had begun... in consequence the

plan for moving up the French reserve group of

divisions was not carried out as agreed. When

the French reserves did begin to arrive, they came

in, many of them, without their guns, without their

cookers, and short of ammunition.

Does not this convey a picture of the Fifth

Army's fight as a tragedy rather than a defeat?

And does not imagination seize an impression

of the bitter trial of Gough and of

Haig before so dreadful a misunderstanding in

an hour of fate? No wonder that on Sunday.

March 24. Haig urgently represented the

necessity for one supreme command for the

Allied armies!

As for the Fifth Army's fight in the fog

(which probably helped them) the record

stands for all to read of how in Maxse's

18th Corps eight battalions fought to the last

in the front zone of the battle and of their

numbers only 50 men returned; how the 36th

(Ulster) Division, repulsed several at-

tacks on their redoubts, and the Inniskilling

Fusiliers and the Royal Irish Rifles stood

their ground till they were annihilated. save

for two tiny parties which cut their way back;

how, of the 14th Division, when, at length,

retreat was ordered, only three battalions

could muster more than a hundred each; how

the 53th Division, outnumbered, outflanked,

and decimated by four German divisions, fought

its gallant rearguard action towards the

French supports, which seemed never to be

going to arrive; and the epic defence of the

left flank and part of Byng's right against

the assault of Marwitz's army at Cambrai.

The retreat of the Fifth Army after the first

day was by order: it was directed to fight a

rearguard action to avoid a break through

until newly-arranged reinforcements could

arrive. The Australians about a week later

saw only the shattered remnants of an army.

which the event proved to have sacrificed it.

self not in vain.

SM Herald

22/3/30.

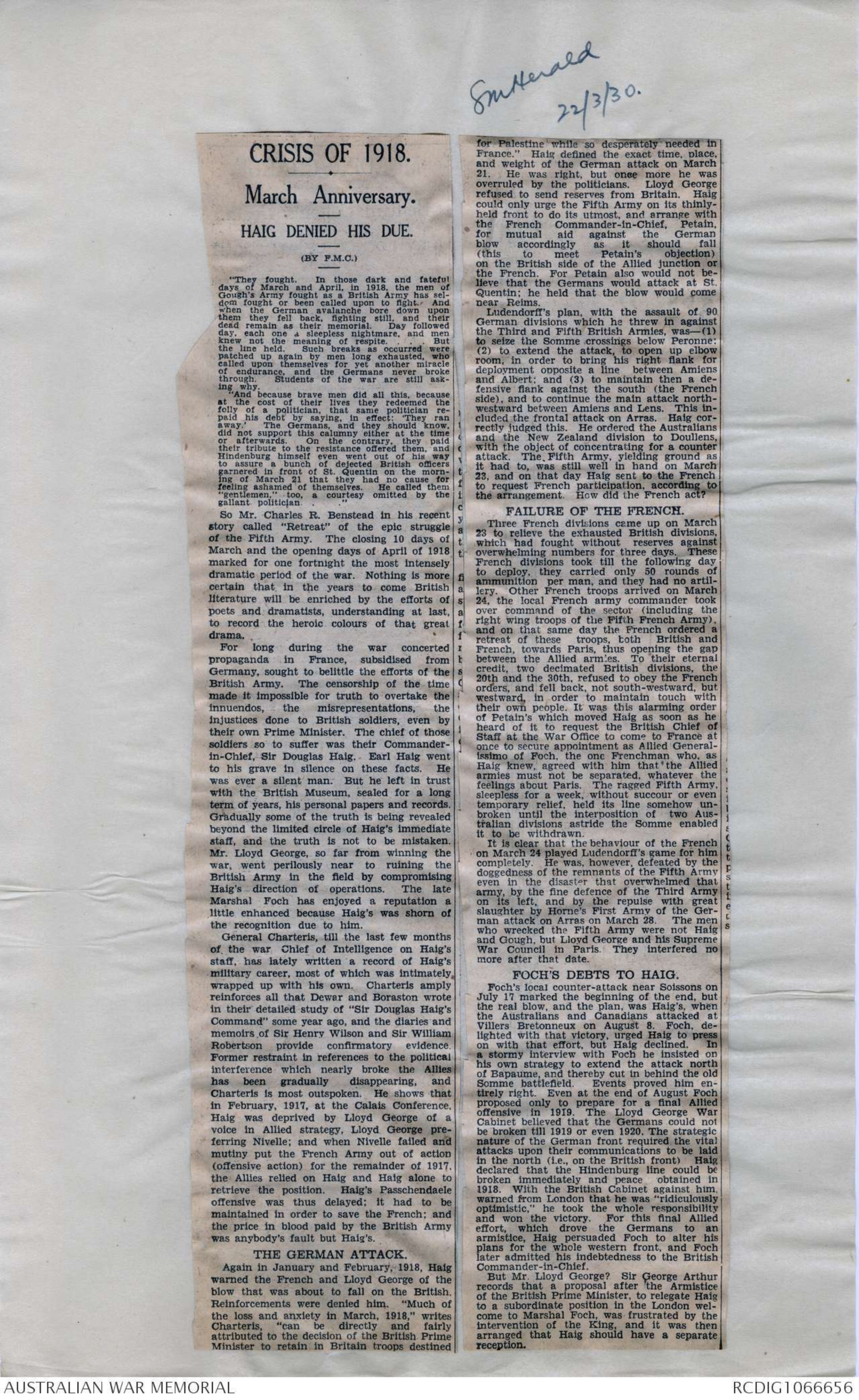

CRISIS OF 1918.

March Anniversary.

HAIG DENIED HIS DUE.

(BY F.M.C.)

"They fought. In those dark and fateful

days of March and April, in 1918, the men of

Gough's Army fought as a British Army has

seldom fought or been called upon to fight. And

when the German avalanche bore down upon

them they fell back, fighting still, and their

dead remain as their memorial. Day followed

day, each one a sleepless nightmare, and men

knew not the meaning of respite .... But

the line held. Such breaks as occurred were

patched up again by men long exhausted, who

called upon themselves for yet another miracle

of endurance, and the Germans never broke

through. Students of the war are still asking

why.

"And because brave men did all this, because

at the cost of their lives they redeemed the

folly of a politician, that same politician repaid

his debt by saying, in effect: "They ran

away". The Germans, and they should know,

did not support this calumny either at the time

or afterwards. On the contrary, they paid

their tribute to the resistance offered to them, and

Hindenburg himself even went out of his way

to assure a bunch of dejected British officers

garnered in front of St. Quentin on the morning

of March 21 that they had no cause for

feeling ashamed of themselves. He called them

"gentlemen" too, a courtesy omitted by the

gallant politician.

So Mr. Charles R. Benstead in his recent

story called Retreat of the epic struggle

of the Fifth Army. The closing 10 days of

March and the opening days of April of 1918

marked for one fortnight the most intensely

dramatic period of the war. Nothing is more

certain that in the years to come British

literature will be enriched by the efforts of

poets and dramatists, understanding at last,

to record the heroic colours of that great

drama.

For long during the war concerted

propaganda in France, subsidised from

Germany, sought to belittle the efforts of the

British Army. The censorship of the time

made it impossible for truth to overtake the

innuendos, the misrepresentations, the

injustices done to British soldiers, even by

their own Prime Minister. The chief of those

soldiers so to suffer was their Commander-

in-Chief, Sir Douglas Haig. Earl Haig went

to his grave in silence on these facts. He

was ever a silent man. But he left in trust

with the British Museum, sealed for a long

term of years, his personal papers and records.

Gradually some of the truth is being revealed

beyond the limited circle of Haig's immediate

staff, and the truth is not to be mistaken.

Mr. Lloyd George, so far from winning the

war, went perilously near to ruining the

British Army in the field by compromising

Haig’s direction of operations. The late

Marshal Foch has enjoyed a reputation a

little enhanced because Haig's was shorn of

the recognition due to him.

General Charteris, till the last few months

of the war Chief of Intelligence on Haig's

staff, has lately written a record of Haig's

military career, most of which was intimately

wrapped up with his own. Charteris amply

reinforces all that Dewar and Boraston wrote

in their detailed study of Sir Douglas Haig's

Command some year ago, and the diaries and

memoirs of Sir Henry Wilson and Sir William

Robertson provide confirmatory evidence.

Former restraint in references to the political

interference which nearly broke the Allies

has been gradually disappearing, and

Charterls is most outspoken. He shows that

in February, 1817, at the Calals Conference.

Haig was deprived by Lloyd George of a

voice in Allied strategy, Lloyd George

preferring Nivelle; and when Nivelle failed and

mutiny put the French Army out of action

(offensive action) for the remainder of 1917.

the Allies relied on Haig and Haig alone to

retrieve the position. Haig's Passchendaele

offensive was thus delayed; it had to be

maintained in order to save the French; and

the price in blood paid by the British Army

was anybody's fault but Haig's.

THE GERMAN ATTACK.

Again in January and February, 1918, Haig

warned the French and Lloyd George of the

blow that was about to fall on the British.

Reinforcements were denied him. Much of

the loss and anxiety in March, 1918, writes

Charteris, can be directly and fairly

attributed to the decision of the British Prime

Minister to retain in Britain troops destined)

for Palestine while so desperately needed in

France." Haig defined the exact time, place.

and weight of the German attack on March

21. He was right, but once more he was

overruled by the politicians. Lloyd George

refused to send reserves from Britain. Haig

could only urge the Fifth Army on its

thinly-held front to do its utmost, and arrange with

the French Commander-in-Chief, Petain,

for mutual aid against the German

blow: accordingly as it should fall

(this to meet Petain’s objection)

on the British side of the Allied junction of

the French. For Petain also would not believe

that the Germans would attack at St

Quentin; he held that the blow would come

near Reims.

Ludendorff's plan, with the assault of 90

German divisions which he threw in against

the Third and Fifth British Armies, was -(1)

to seize the Somme crossings below Peronne:

(2) to extend the attack, to open up elbow

room, in order to bring his right flank for

deployment opposite a line between Amiens

and Albert: and (3) to maintain then a

defensive flank against the south (the French

side), and to continue the main attack north-

westward between Amiens and Lens. This

included the frontal attack on Arras. Haig

correctly judged this. He ordered the Australians

and the New Zealand division to Doullens,

with the object of concentrating for a counter

attack. The, Fifth Army, yielding ground as

it had to, was still well in hand on March

23, and on that day Haig sent to the French

to request French participation, according to

the arrangement. How did the French act?

FAILURE OF THE FRENCH.

Three French divisions came up on March

23 to relieve the exhausted British divisions,

which had fought without reserves against

overwhelming numbers for three days. These

French divisions took till the following day

to deploy, they carried only 50 rounds of

ammunition per man, and they had no

artillery. Other French troops arrived on March

24, the local French army commander took

over command of the sector (including the

right wing troops of the Fifth French Army).

and on that same day the French ordered a

retreat of these troops, both British and

French, towards Paris, thus opening the gap

between the Allied armies. To their eternal

credit, two decimated British divisions, the

20th and the 30th, refused to obey the French

orders, and fell back, not south-westward, but

westward in order to maintain touch with

their own people. It was this alarming order

of Petain's which moved Haig as soon as he

heard of it to request the British Chief of

Staff at the War Office to come to France at

once to secure appointment as Allied

General-issimo of Foch, the one Frenchman who. as

Haig knew, agreed with him that the Allied

armies must not be separated, whatever the

feelings about Paris. The ragged Fifth Army

sleepless for a week, without succour or even

temporary relief, held its line somehow

unbroken until the interposition of two

Australian divisions astride the Somme enabled

it to be withdrawn.

It is clear that the behaviour of the French

on March 24 played Ludendorff's game for him

completely. He was, however, defeated by the

doggedness of the remnants of the Fifth Army

even in the disaster that overwhelmed that

army, by the fine defence of the Third Army

on its left, and by the repulse with great

slaughter by Horne's First Army of the Ger-

man attack on Arras on March 28. The men

who wrecked the Fifth Army were not Haig

and Gough, but Lloyd George and his Supreme

War Council in Paris. They interfered no

more after that date.

FOCH'S DEBTS TO HAIG.

Foch's local counter-attack near Soissons on

July 17 marked the beginning of the end, but

the real blow, and the plan, was Haig's, when

the Australians and Canadians attacked at

Villers Bretonneux on August 8. Foch, delighted

with that victory, urged Haig to press

on with that effort, but Haig declined. In

a stormy interview with Foch he insisted on

his own strategy to extend the attack north

of Bapaume, and thereby cut in behind the old

Somme battlefield. Events proved him entirely

right. Even at the end of August Foch

proposed only to prepare for a final Allied

offensive in 1919. The Lloyd George War

Cabinet believed that the Germans could not

be broken till 1919 or even 1920. The strategic

nature of the German front required the vital

attacks upon their communications to be laid

in the north (i.e., on the British front) Haig

declared that the Hindenburg line could be

broken immediately and peace, obtained in

1918. With the British Cabinet against him.

warned from London that he was "ridiculously

optimistic", he took the whole responsibility

and won the victory. For this final Allied

effort, which drove the Germans to an

armistice, Haig persuaded Foch to alter his

plans for the whole western front, and Foch

later admitted his indebtedness to the British

Commander-in-Chief.

But Mr. Lloyd George? Sir George Arthur

records that a proposal after the Armistice

of the British Prime Minister, to relegate Haig

to a subordinate position in the London welcome

to Marshal Foch, was frustrated by the

intervention of the King, and it was then

arranged that Haig should have a separate

reception.

H.N. March

Aug 1918

TELEPHONE NOS.

F2597.

F 2598.

TELEGRAPHIC ADDRESS

"AUSWARMUSE."

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA.

COMMUNICATIONS TO BE ADDRESSED TO

"THE DIRECTOR."

IN REPLY PLEASE QUOTE

No. 12/4/10.

"They gave their lives. For that public gift they

received a praise which never ages and a

tomb most glorious - not so much the tomb in

which they lie, but that in which their fame

survives, to be remembered for ever when occasion

comes for word or deed......"

AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL.

POST OFFICE BOX 214 D

EXHIBITION BUILDINGS, MELBOURNE

24th May, 1930.

Dear Mr. Bazley,

"Who won the War".

You will be interested in the attached photostat

copies of cuttings from the London "Evening Standard" of the

2lst March and 5th April 1929, together with copy of

correspondence between General Monash and Sir Granville

Ryrie. These copies may be retained if you so desire.

Yours sincerely,

J Shillom

Mr. A. W. Bazley

c/o Official Historian,

Victoria Barracks,

PADDINGTON,. NSW.

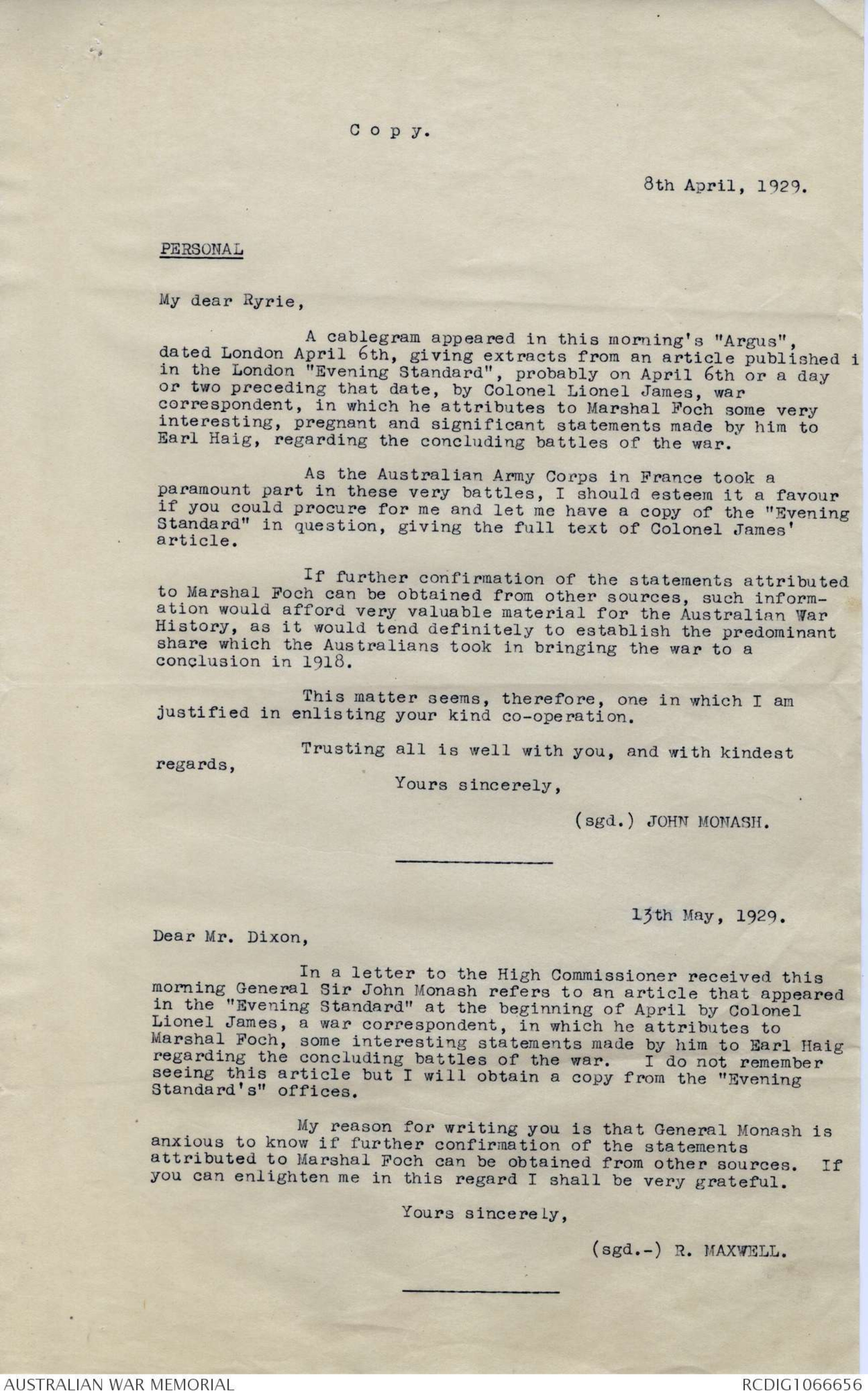

Copy.

8th April, 1929.

PERSONAL

My dear Ryrie,

A cablegram appeared in this morning’s "Argus"

dated London April 6th, giving extracts from an article published i

in the London "Evening Standard", probably on April 6th or a day

or two preceding that date, by Colonel Lionel James, war

correspondent, in which he attributes to Marshal Foch some very

interesting, pregnant and significant statements made by him to

Earl Haig, regarding the concluding battles of the war.

As the Australian Army Corps in France took a

paramount part in these very battles, I should esteem it a favour

if you could procure for me and let me have a copy of the "Evening

Standard" in question, giving the full text of Colonel James'

article.

If further confirmation of the statements attributed

to Marshal Foch can be obtained from other sources, such

information would afford very valuable material for the Australian War

History, as it would tend definitely to establish the predominant

share which the Australians took in bringing the war to a

conclusion in 1918.

This matter seems, therefore, one in which I am

justified in enlisting your kind co-operation.

Trusting all is well with you, and with kindest

regards,

Yours sincerely,

(sgd.) JOHN MONASH.

13th May, 1929.

Dear Mr. Dixon,

In a letter to the High Commissioner received this

morning General Sir John Monash refers to an article that appeared

in the "Evening Standard" at the beginning of April by Colonel

Lionel James, a war correspondent, in which he attributes to

Marshal Foch, some interesting statements made by him to Earl Haig

regarding the concluding battles of the war. I do not remember

seeing this article but I will obtain a copy from the "Evening

Standard’s" offices.

My reason for writing you is that General Monash is

anxious to know if further confirmation of the statements

attributed to Marshal Foch can be obtained from other sources. If

you can enlighten me in this regard I shall be very grateful.

Yours sincerely,

(sgd.-) R. MAXWELL.

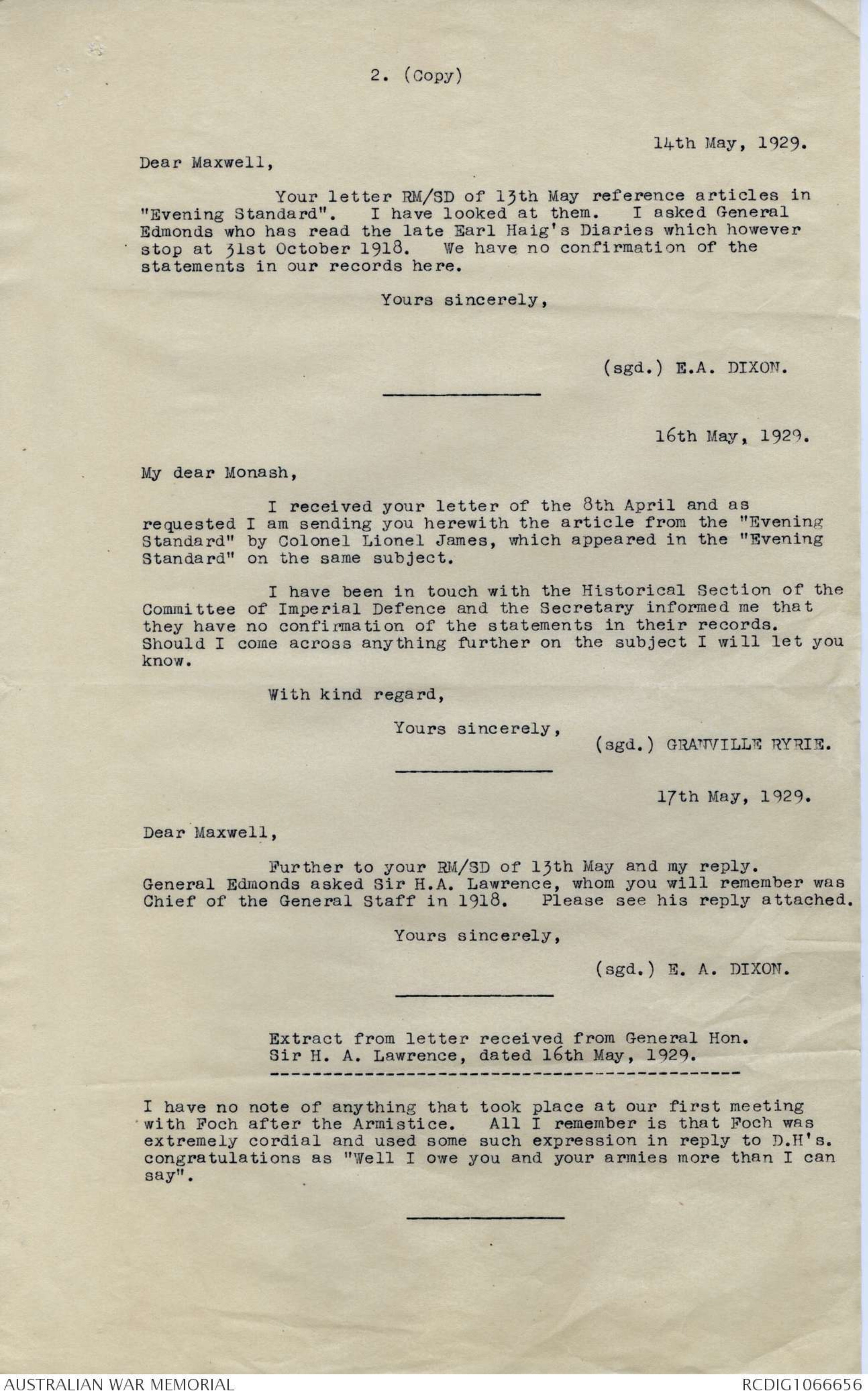

2. (Copy)

14th May, 1929.

Dear Maxwell,

Your letter RM/SD of 13th May reference articles in

"Evening Standard". I have looked at them. I asked General

Edmonds who has read the late Earl Haig's Diaries which however

stop at 31st October 1918. We have no confirmation of the

statements in our records here.

Yours sincerely,

(sgd.) E.A. DIXON.

16th May, 1929.

My dear Monash,

I received your letter of the 8th April and as

requested I am sending you herewith the article from the "Evening

Standard" by Colonel Lionel James, which appeared in the "Evening

Standard" on the same subject.

I have been in touch with the Historical Section of the

Committee of Imperial Defence and the Secretary informed me that

they have no confirmation of the statements in their records.

Should I come across anything further on the subject I will let you

know.

With Kind regard,

Yours sincerely,

(sgd.) GRANVILLE RYRIE.

17th May, 1929.

Dear Maxwell,

Further to your RM/SD of 13th May and my reply.

General Edmonds asked Sir H.A. Lawrence, whom you will remember was

Chief of the General Staff in 1918. Please see his reply attached.

Yours sincerely,

(sgd.) E. A. DIXON.

Extract from letter received from General Hon.

Sir H. A. Lawrence, dated 16th May, 1929.

I have no note of anything that took place at our first meeting

with Foch after the Armistice. All I remember is that Foch was

extremely cordial and used some such expression in reply to D.H's.

congratulations as "Well I owe you and your armies more than I can

say".

3. (Copy)

2lst May, 1929.

Dear Dixon,

Thanks for your letter of the 14th and 17th

instant in regard to the Statements made by Colonel Lionel

James in the article in the "Evening Standard". I have

passed on the information to General Monash. The extract

from the letter from General Lawrence is interesting and

General Monash, I am sure, will be glad to have it.

Yours sincerely,

(sgd.) R. MAXWELL.

2lst May, 1929.

My dear Monash,

Further to my letter of the 16th instant, I have

just received from the Historical Section of the Committee of

Imperial Defence the enclosed extract from a letter received by

General Edmonds from General the Hon. H. A. Lawrence which may

be of interest to you.

With Kind regards,

Yours sincerely,

(Sgd.) GRANVILLE

RYRIE.

Evening Standard 21/4/29

HOW FOCH FOUGHT

PRIVATE JEALOUSIES.

By COL. LIONEL JAMES, C.B.E., D.S.O.

FIELD-MARSHAL FOCH, Marshal

of France, was the great

Commander-in-Chief of the

Allied Armies in France in

1918, when they overthrew the remaining

energy of the German Empire,

seventy-eight years ago there was born

to a superior bourgeois family in a drab

little house, in a drab little square, in the

drab little provincial town of Tarbes, in the

Pyrenees, an infant who was destined to

rank with the long list of distinguished

Marshals of France and to command armies

in the field the like of which neither they nor

any of the makers of France's glorious military

history had ever dreamed. Three

million men, of whom close on a million

were of the British race. It was enough to

make Emperor Napoleon turn in his

grave!

The curious part of this great development of

the "Wheel of Chance" is that, beyond being

a studious youth, the great Marshal showed

little promise for the wonderful career that was

to be his. He was educated at Motz. It was

fortunate that his parents selected the Alsatian

Province, for it had much to do in the shaping

Photo - see original document

of his mind for the future. Foch was just too

young to bear arms in the Franco-Prussian war

of 1870, but he was old enough to appreciate the

humiliation of France, and this appreciated

influence the who of his military career.

From the day he entered the Military

Academy the art of war, in view of its many and

increasing developments, engrossed the whole of

his time. His actual regimental service was

normal, but his military knowledge and his

philosophical application of this knowledge

brought him in the the front rank of thinking

officers of the French army, and he was in due

course appointed Commandant of the French

equivalent of our Staff College. He had given to

the world two military treatises, one "The

Principles of War" the other "The Conduct of

War". Both these works are of outstanding

merit, and were usually place on the bookshelf

of the military student beside those of Causewitz

and Jonnini.

Foch was a British Field-Marshall, and our

interest in his life must take a personal touch.

It was while Foch was Commandant of the Ecole

Supéricure de la Guerre that he first came into

touch with the late Field-Marshal Sir Henry

Wilson.

Preparations for

"The Day".

Wilson had read Foch's works and Staff College

appreciations and lectures, and largely through

them was possessed of the view that Germany

was developing her naval and military strength

with on object-and one object only.

During one of his many visits to the Franco-German

frontier Wilson came into personal

touch with Foch, and the, as the heads of the

same educational establishments in their

respective countries, official acquaintance ripened into

a close admiration and friendship.

In 1911 Sir Henry showed the writer a

memorandum he had adapted from one of

Foch's appreciations which forecast the actual

German plan of invasion of France with an

accuracy that was complete in nearly every

detail.

Foch saw the necessity of British co-operation

when Germany should select the day. His fear

was that, though Britain might be navally

prepared, yet her military effort might be too late.

Although Foch did not anticipate, or hope for,

an early British contribution to the campaign in

deciding strength, yet he knew the moral value

that a British Expeditionary Force, fighting on

French soil, would bring to his own country: and

he justly appreciated that the British Navy was

an essential to France's success.

Wilson went from Camberley to the Sub-Chief

of Operations Section of the War Office, and

from the moment he took charge of that

department he devoted every hour of his time and

every ounce of his energy to create the Expeditionary

Force that his friend Foch had convinced

him was essential.

We have it from Wilson's diary how, responsive

to Foch's inspirations, he worked at

"conversations" before the two General Staffs,

and how, avoiding the suspicion of the

politicals, a British Expeditionary Force was

fashioned that would be instantly mobile, and

also a liaison between the directing soldiers of

each radius was placed upon the only possible

basis that could be developed into successful

co-operation. We own this to the little-known

Foch's influence upon the Operations Section of

our own War Department.

Then the blow fell almost exactly as Foch

had foretold it. It found Foch in command

of the 13th French Division, but he was, of

course, destined for higher things. We now

know that, although Foch's strategical teachings

were right, the tactical handling of the

modern battle adopted by the French État-Major

was wrong.

The battle of Charleroi and the Meuse might

well have lost the war in the prodigality with

which the flower of France's manhood was

hurled into the charnel house. In this Foch

was only a subordinate. But doubtless his

preconceived tactical convictions were modified,

and his conduct of his portion of the subsequent

battle of the Marne on the immediate

right of the B.E.F. was masterly.

The Victim of

"Personal Influences".

France is a difficult country in which to be

a man of the moment, unless everything is

moving rapidly to a successful issue. Political and

personal influences rend and warp directive

judgment. Private jealousies pervert altruistic

decisions. Foch succumbed to a series of these

stresses. Politicians whose perspective was that

which their mediocrity described saw other

Alexanders amongst the French generals.

Joffre, who had completed, if he had not entirely

designed, the great battle of the Marne,

which really enabled the Allies to win the war

was thrown over and replaced by Nivelle, the

latter to be succeeded by Pétain. But Foch’s

influence was not dead, and through these

trying experiments in High Command the liaison

with the British held firm. This was the marvel

of the war.

Then came the momentous crisis in the spring

of 1918. The French Army was exhausted. It

had been wrung with the tribulations of the

three years of struggle. Charleroi, Notre Dame

de Lorette, Verdun, and the Chemin-des-Dames

had bled it white. It had mutinied to an alarming

degree. Then came the great German effort

in March. The British Fifth Army was bent

back fifty miles and was in dire distress.

Pétain had promised in this event a counter

attack with six French Divisions. Not a single

French soldier was moved. Lord Haig was in

despair. He reported to the Prime Minister

that the war was lost unless there were a unified

Command of the Allied Armies. He suggested

Foch, who at the time was employed in that

curious development of an independent War

Not in Agreement

with Haig's Design

The Allied situation was desperate when

Foch accepted this responsibility. The enemy

was knocking at the door at Amiens, and was

developing another massed attack upon the

British on the Lys. The American reinforcements

were arriving: but were as yet raw as

soldiers and inexperienced in staff duties. But

Foch, in the chateau where he had established

his H.Q, was unperturbed. He viewed the

situation calmly

He chose, with infinite taste considering the

delicacy of his supreme powers, to control by

what he called "directives." These were

orders issued in the form of advice. The scheme

worked well, and Foch was able within a week

of taking up his new office to say of the enemy:

"Villers Bretonneux, oui —Amiens, jamais."

Then followed the stupendous battling in the

north—the epic struggle for Mont Kemmell

Fresh French divisions marched up from the

South, tired British divisions trained down to

the Chemin-des-Dames. The Allied Armies for

the first time were one Army. In May the

Germans’ efforts were spent. They had played

their last card, but Foch, as the supreme

director of the defence, had "trumped it," and

the "rubber" was won.

it remained now to win "the game." The

Americans were coming in their thousands, and

the first arrivals had been trained into efficient

soldiers. Foch issued his "directives," but

there was no arrogance in his sway. He consulted

his Allied Commanders as confrères

rather than as their superior. He set them

their own portions to develop as they opined

their own troops would do them best!

With the design of the great battles with

which the British Commander-in-Chief finished

the war it is only fair to say that Foch and

the French État-Major were not in agreement,

but Foch was wise enough to realise that there

were two points of view. His admiration for

Haig’s genius governed his decision, and when

that decision proved right, Foch, the

general-issimo, was the first to congratulate his British

confrère, and to say that his conception and

development of the final operations would go

down to history, in all time, as classics of how

a modern victory was conceived and gained.

[Mr. Compton Mackenzie's article in the Eternal

Punishment series will appear to-morrow.]

AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL

Sam scott

Sam scottThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.