Charles E W Bean, Diaries, AWM38 3DRL 606/246/1 - 1916 - 1929 - Part 4

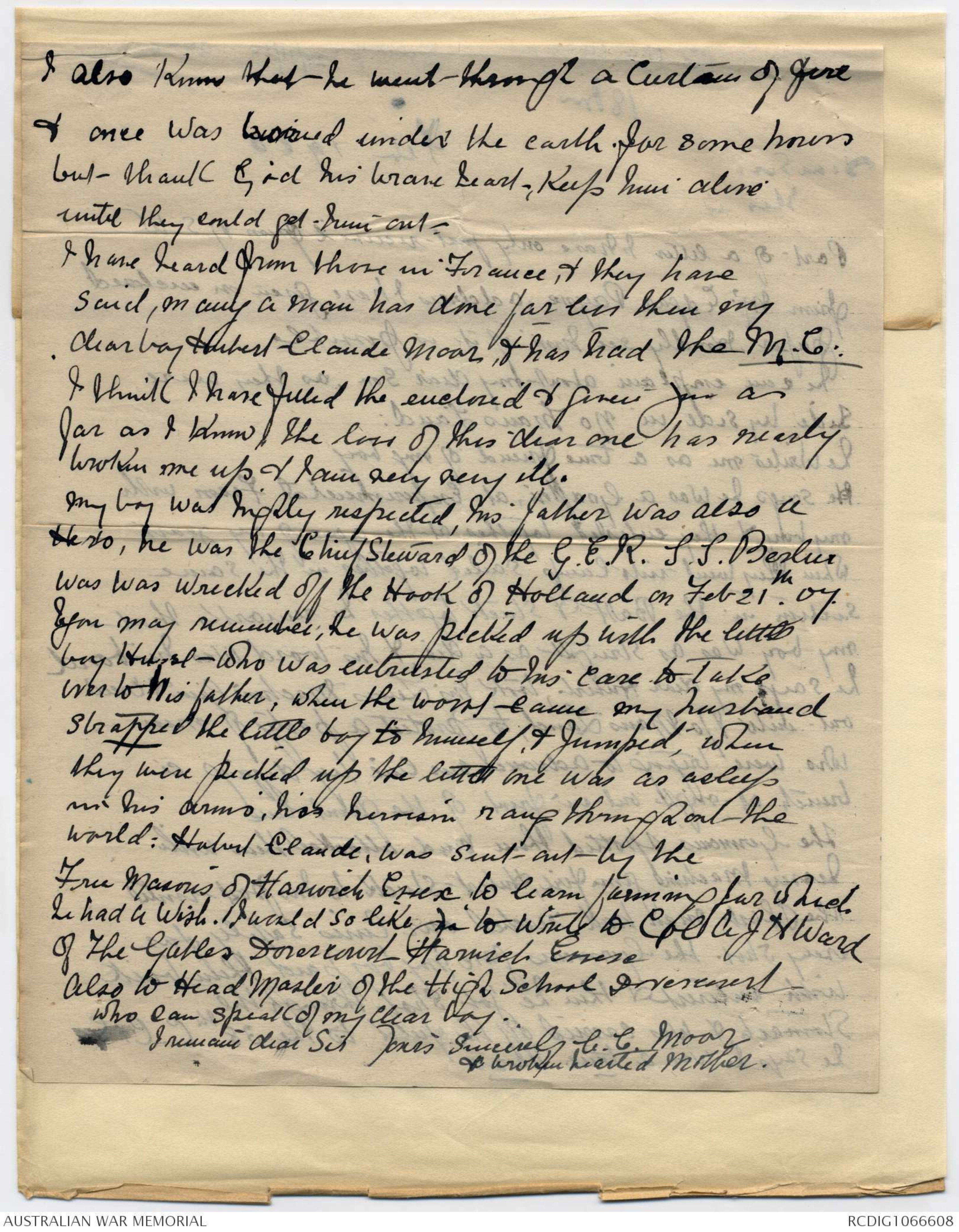

& also know that he went through a curtain of fire

& once was buried under the earth for some hours

but thank God his brave heart, keep him alive

until they could get him out.

I have heard from those in France, & they have

said, many a man has done far less then my

dear boy Hubert Claude Moor, & has had the M.C..

I think I have filled the enclosed & given you as

far as I know, the loss of this dear one has nearly

broken me up & I am very very ill.

My boy was highly respected, his father was also a

Hero, he was the Chief Steward of the G.E.R. S. S. Berlin

was was wrecked off the Hook of Holland on Feb 21th 07.

You may remember, he was picked up with the little

boy Hubert - who was entrusted to his care to take

over to his father, when the waves came my husband

strapped the little boy to himself, & jumped, when

they were picked up the little one was as asleep

in his arms, his heroism rang throughout the

world: Hubert Claude was sent out by the

Free Masons of Harwich Essex to learn farming for which

he had a wish. I would so like is to write to Cpl A J H Ward

of the Gables Dovercourt Harwich Essex

Also to Head Master of the High School Reverend

who can speak of my dear boy.

I remain dear Sir

Yours Sincerely C.C. Moor

& broken hearted Mother.

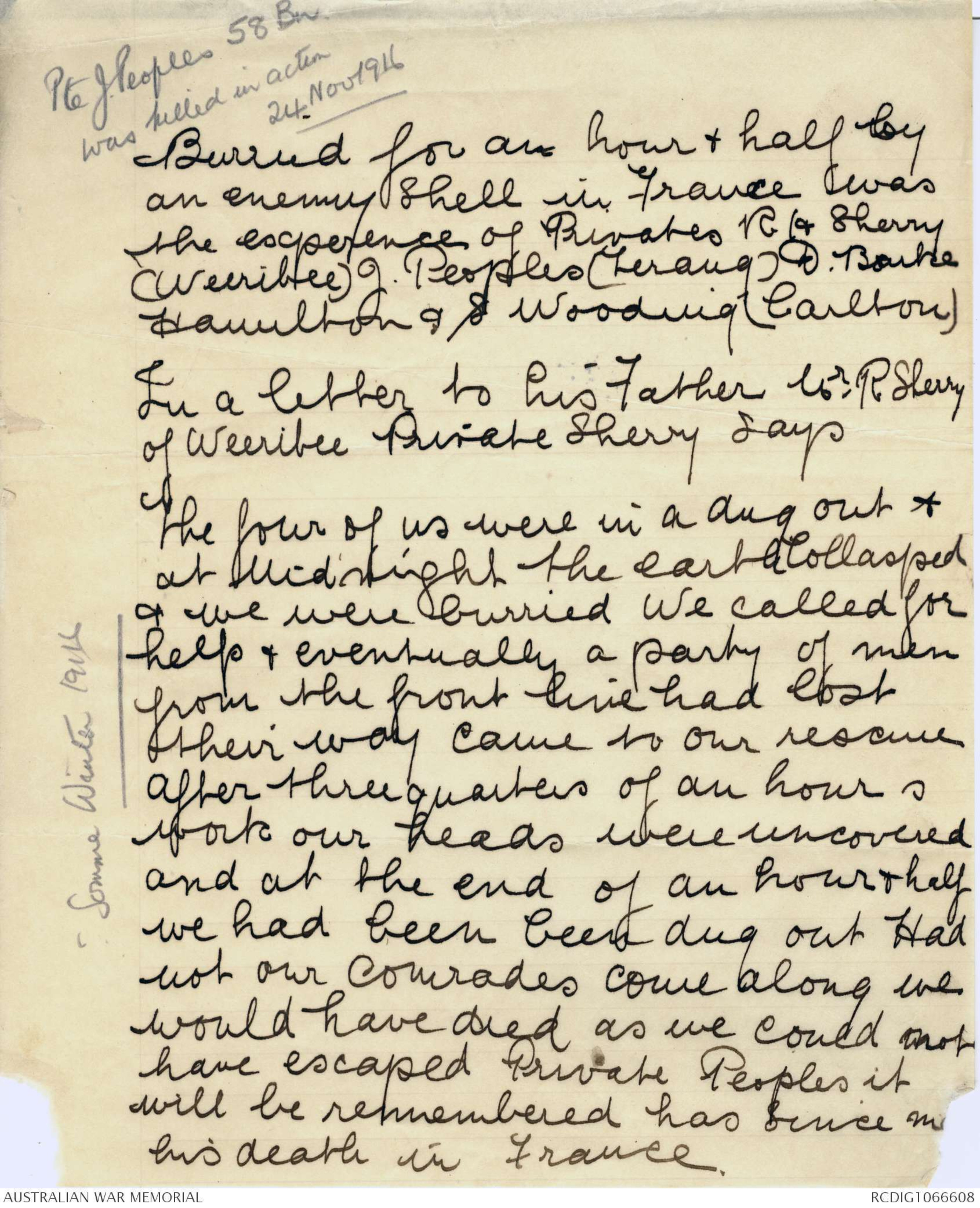

[*Pte J. Peoples 58 Bn

was killed in action

24 Nov 1916*]

Buried for an hour & half by

an enemy shell in France was

the experience of privates R H Sherry

(Weeribee) J. Peoples (Terang) D. Bourke

Hamilton & S Wooding (Carlton)

In a letter to his Father Mr R. Sherry

of Weeribee Private Sherry says

The four of us were in a dug out &

at Midnight the earth collapsed

& we were burried We called for

[*Somme Winter 1916*]

help & eventually a party of men

from the front line had lost

their way came to our rescue

after three quarters of an hours

work our heads were uncovered

and at the end an hour & half

we had been been dug out Had

not our comrades come along we

would have died as we could not

have escaped Private Peoples it

will be remembered has since met

his death in France.

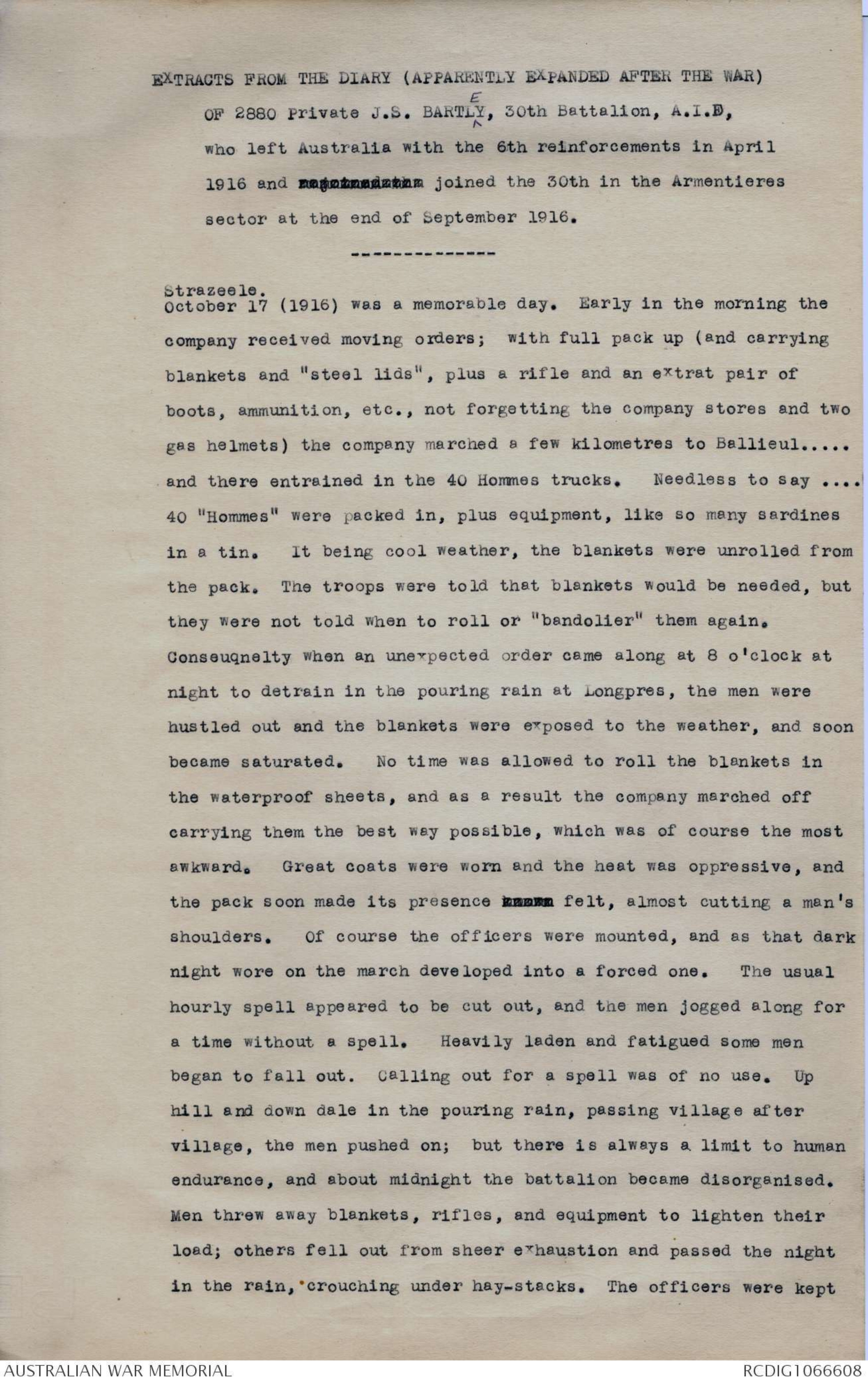

EXTRACTS FROM THE DIARY (APPARENTLY EXPANDED AFTER THE WAR)

OF 2880 Private J.S. BARTL^EY, 30th Battalion, A.I.F,

who left Australia with the 6th reinforcements in April

1916 and anjoinedxthe joined the 30th in the Armentieres

sector at the end of September 1916.

Strazeele

October 17 (1916) was a memorable day. Early in the morning the

company received moving orders; with full pack up (and carrying

blankets and "steel lids", plus a rifle and an extrat pair of

boots, ammunition, etc., not forgetting the company stores and two

gas helmets) the company marched a few kilometres to Ballieul. . . . .

and there entrained in the 40 Hommes trucks. Needless to say . . . .

40 "Hommes" were packed in, plus equipment, like so many sardines

in a tin. It being cool weather, the blankets were unrolled from

the pack. The troops were told that blankets would be needed, but

they were not told when to roll or "bandolier" them again.

Conseuqnelty when an unexpected order came along at 8 o'clock at

night to detrain in the pouring rain at Longpres, the men were

hustled out and the blankets were exposed to the weather, and soon

became saturated. No time was allowed to roll the blankets in

the waterproof sheets, and as a result the company marched off

carrying them the best way possible, which was of course the most

awkward. Great coats were worn and the heat was oppressive, and

the pack soon made its presence known felt, almost cutting a man's

shoulders. Of course the officers were mounted, and as that dark

night wore on the march developed into a forced one. The usual

hourly spell appeared to be cut out, and the men jogged along for

a time without a spell. Heavily laden and fatigued some men

began to fall out. Calling out for a spell was of no use. Up

hill and down dale in the pouring rain, passing village after

village, the men pushed on; but there is always a limit to human

endurance, and about midnight the battalion became disorganised.

Men threw away blankets, rifles, and equipment to lighten their

load; others fell out from sheer exhaustion and passed the night

in the rain, crouching under hay-stacks. The officers were kept

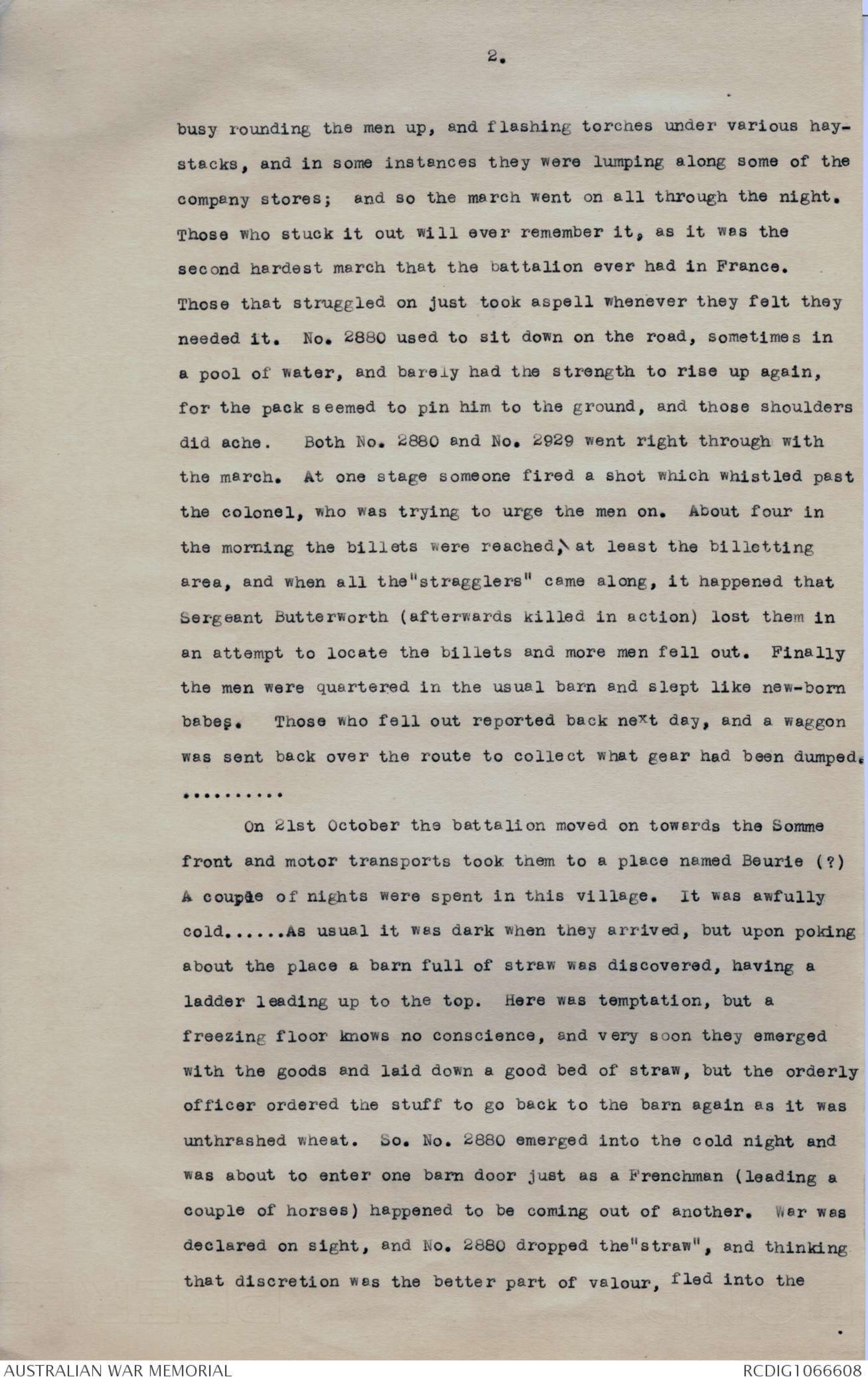

2.

busy rounding the men up, and flashing torches under various haystacks,

and in some instances they were lumping along some of the

company stores; and so the march went on all through the night.

Those who stuck it out will ever remember it, as it was the

second hardest march that the battalion ever had in France.

Those that struggled on just took aspell whenever they felt they

needed it. No. 2880 used to sit down on the road, sometimes in

a pool of water, and barely had the strength to rise up again,

for the pack seemed to pin him to the ground, and those shoulders

did ache. Both No. 2880 and No. 2929 went right through with

the march. At one stage someone fired a shot which whistled past

the colonel, who was trying to urge the men on. About four in

the morning the billets were reached; at least the billetting

area, and when all the "stragglers" came along, it happened that

Sergeant Butterworth (afterwards killed in action) lost them in

an attempt to locate the billets and more men fell out. Finally

the men were quartered in the usual barn and slept like new-born

babes. Those who fell out reported back next day, and a waggon

was sent back over the route to collect what gear had been dumped.

On 2lst October the battalion moved on towards the Somme

front and motor transports took them to a place named Beurie (?)

A couple of nights were spent in this village. It was awfully

cold. . . . . . As usual it was dark when they arrived, but upon poking

about the place a barn full of straw was discovered, having a

ladder 1eading up to the top. Here was temptation, but a

freezing floor knows no conscience, and very soon they emerged

with the goods and laid down a good bed of straw, but the orderly

officer ordered the stuff to go back to the barn again as it was

unthrashed wheat. So. No. 2880 emerged into the cold night and

was about to enter one barn door just as a Frenchman (leading a

couple of horses) happened to be coming out of another. War was

declared on sight, and No. 2880 dropped the "straw", and thinking

that discretion was the better part of valour, fled into the

3.

night with the Frenchman in full pursuit and armed with a pitchfork,

and calling out at intervals "Le Capitaine, Le Capitaine!". But

he was very soon lost in the darkness. . . . . . . . . . . .

On the 27th October the battalion marched to "Hungry Hill",

so named on account of the small issue of rations. On this hill a

tarpaulin was rigged up for shelter, and 40 men (one platoon) were

placed underthis, lying on their sides, and remaining like that all

night. If they wanted to turn, then all had to turn together.

Anyhow it was better than being out in the frost all night. . . . . . . . .

Hungry Hill was not far from Flers, and well under shell-fire, and

many a freeze the men did of a night, when placed and packed in

those dugouts of the "get-out-now-and-again-for-a-rest" type.

No. 2880 well recollects the duck-board fatigue (the Duckboard

Harriers) from the Hungry Hill to Needle Dump, along the duckboards,

the night he and Donniger and others got lost coming back. No one

seemed to care for that kind of fatigue, for it was no "cop". The

boards were often dumped by men who were too exhausted to carry

them, and by others who deliberately threw them away. . . . . . . . On the

23rd October the company moved from Hungry Hill to the support line

at Flers. As usual the men were heavily laden, and No. 2880 fell

back a little, owing to carrying a bucket of Mills bombs, till

relieved of the load, when he came up again with the "mob". Before

entering Fish Alley, it became noticeable that dead Tommies were

lying about. . . . . . Working their way up Fish Alley, and past Flers

dump, they took over from the Tommies. Fish Alley was nothing more

or less than a creek, and mud was abundant, and the troops had no

gum-boots. . . . A little on the right was the village of Flers, with

its graveyard of tanks and dead mules, and its cellars containing

German dead. Fritz was constantly shelling the village and support

line, and it was a lively place to be in. For ten days and nights

the company occupied this trench, under Captain Cheeseman and "Dad"

White, and truly they lived an amphibious life. . . . . . . . . . .

During the ten days in a stunt was to have taken place. . . . . .

but owing to the wet weather and the mud the attack, after waiting

4.

night after night, was postponed. To attempt to walk across No

Mans Land was a sure certainty of bogging up to the waist. So the

time was spent in the line and fatigue work. Donniger and Dad

Easlie (killed in action later on) and others used to go across

to the village and bring back good water, vegetables, and coal.

The Huns had left the vegetables planted. . . . . . They were boiled

mostly in yellow shell-hole water, as the village was only

accessible during foggy weather, and evn then it was shelled.

Being in support lines it was possible to have a fire. Braziers

were made, and the coal from the village became good fuel. This

coal was a compound and was the same shape and a little larger t

than an egg. . . . . . . Those who remember Dad Easlie will always

remember his "black-fellow" fires, and the manner in which he used

to crouch over them, having his pipe constantly in his mouth and

carryong on in his dry old manner. . . . . . . . . .

A host of sap fatigues were done, as the trench began to

fallin owing to the nature of the earth and the rainy weather.

Thus began the long winter campaign of 1916-17 on the Somme, The

mud was awful; the men shortened their great coats by cutting

off a width from the bottom with their bayonets, as the weight of

the clinging wet mud was too cumbersome to carry about. . . . . . . .

Later on it came out in orders that coats were not to be cut, and

tags were issued so that the coat could be raised above the

knees like the French pattern. . . . . The. . .

The transport (mules) brought up the rations to a certain

point by night, and then they became man-handled to the trenches.

Often a ration party would come under shell-fire and lose a few

men, and so they became "buckshee" (if, as sometimes, some of the

rations would be dumped) for the first party that chanced to come

along, while the men in the trenches went short.

During the trip in at Flers Fritz used a great deal of

gas shells, and got a few casualties. There was no shelter for

the men. Entrenching tools came in useful for scraping a funkhole,

but, when this was done, the bank collapsed, and so later on it

5.

came out in orders that "men must not weaken the parapet by digging

in the side of the trench", but must stand out in the weather. But

the "heads" always had their dugouts. . . . . . . . . . . .

In those days it usually took six hours for a stretcher-bearing

party to carry out a wounded man to the dressing aid station. It was an

awful job struggling through the mud, and a pitiful sight to see the

mules and horses bogged, with only their heads above the surface of

the mud, left there to die. . . . . . . . . .

However the stunt did not come off and the troops moved back

to Hungry Hill. . . . . . . . . . There is no doubt that the issue of rum

(an issue was but a little) to the troops nin the trenches during

those cold and bitter nights on the Somme (when often men had to

remain for days at a time standing in water) saved many lives, and

brought a little cheer and warmth along with it. Let it be said

here, that it was never issued before a "hop over", but afterwards,

when the job was done.

The battalion now prepared to move out for a spell. Fricourt

was the first stop en route. A night was spent there, and, while

the packs were stacked outside in the mud, the men were packed

tightly in bow-huts. The troops got but little rest that night, as

the sergeants (or rather a few of them) had been at the rum jar. . . . . .

But, "If the Sergeants drink your rum, never mind. . . . . .

(Then followed a spell at Vignacourt)

On the morning of the 16th there was a long march to

Montauban, a village completely wiped off the map. . . . . . . Upon arrival

there were a few huts. Turning in from the main road the men

struggled past an old half-buried cart to dodge a bog-hole, and after

that it was a case of struggling on through the mud to the hut door.

Once inside the hut it was "firm ground", but if one stepped outside

he was a sure bird to bog to the knees. About eighty men were

placed in a hut for a start, plus equipment, and it was a case of

sitting up all night, as the normal accommodation was forty. The hut

floor was usually a few inches deep with mud, but later on things

improved. Duckboards were laid all over the place, and a corduroy

6.

road was made leading out on to the main road, and more huts were

erected.

The taps became frozen and trips had to be made to the water-point,

where there was a large tank up the main road and past Easy

Corner. It was no joke going along that icy slippery road of a

night to fill the "fannies". Fires had to be lighted to start the

flow of water. One dark night about ten o’clock it was discovered

that a dixie had to be filled for the "babblers" (cooks). Sergeant

Curran (afterwards killed in action) dealt the cards to see which man

had to go. As usual the lot fell on the new reinforcements, and No.

2880 and 2929 were detailed to go. Now there was no doubt whatever

that the cards were always fixed before dealing, and so No. 2929

rose to the occasion and spoke his mind about the matter. After

that night the card-dealing stunt was cut right out.

In the hut at Montauban belonging to No. 15 Platoon were a

jolly good crowd. . . . . . . . . Harshups were encountered at Montauban.

Rations were low, and while out of the line for aspellm a spell many

arduous fatigues were done. Esquimaux dampmm dump (Delville Wood),

past Waterlot Farm to Needle Dump, was a favourite fatigue track.

Chats were plentiful, and at one stage it was nine weeks before the

men could get a bath or a change of underclothing. And the n it was

a "Russian Bath", so called because the men had to wait out in the

snow, and rush in and out again, after standing for four minutes

under what was called a shower. . . . . . . . . . . .

On the 17th of November the Battalion moved to Trones Wood,

and was occupied with fatigue work, carrying duckboard to Needle Dump

and round about. At Waterlot Farm was Padre Ward's soup kitchen;

every man going in or coming out of the line always received a hot

drink of cocoa or soup, when passing, and the Padre spent many a long

night during that cold winter looking after thr boys. . . . . . . .The place

run by the Australian Comforts Fund and was a typical "buckshee"

house. Padre did not care to hear any swearing about the place, and

had a notice erected which bore this sign: "Do not loiter around, as

it gives the place a bad name. He was very popular with the boys,

and not long afterwards. . . . was invalided home to Aussie.

7.

The next day the battalion moved up towards the line and occupied

the trenches "Cow" and "Mail" (afterwards called Blighty Trench).

Captain Barbour (Achi) was in command of the company, and one

night they had to move to Rose Trench, which was quite handy,

being a little further ahead. But as usual the captain got the

boys lost, and after bogging them along through the mud and

dodgning shells, they found themselves getting into a new sap,

upon which the Pioneers were busy working, and were just in time

to see a shell burst and kill two of the Pioneers. But it was

the wrong trench. Eventually Rose Trench was reached, in the

pouring rain at four o'clock in the morning; it was full of

water, and there was no shelter save one old exposed Hun shelter,

which was very soon occupied.

So, wet to the skin and exhausted, the men had to make the

best of things. But they were quite used to that. Talk about

Cap. Bairnsfather's old Bill! Why he wasn't in it, compared

with the experience of No. 2929 and Corporal Pickering, who found

a small funkhole and sat down till morning with their legs in two

feet of water, while No. 2880 and Donniger sat on the an embankment

and placed a waterproof sheet over their heads, and sat in the

rain till morning broke. And then there was a hunt for "possies",

For four nights No. 2880 and 2929 slept istting up in a most

awkward and cramped position on a stairway leading down to a dugout.

Fatigues were carried out during the night. After a couple

of nights No. 2929 got "fed up" with it, and threatened to lay his

water-proof sheet on the top of the dugout, and sleep there.

However he was persuaded to remain where he was by his mate, and

that very night a big shell landed fair on top of the dugout and

shook those up inside it. . . . . . . . the shell failed to burst.

Rose Trench was in an awful state, being a real typical Somme

trench. At night parties used to go back for rations and water,

and silently wend their way along the duckboards and throughbthe

mud. Occasionally a flash from a gun would blind their eyes, and

some of the "shell-hole kings" would plunge off the duckboards

8.

right into a shell-hole full of water. As the party moved "at

the toot" (in all haste) in order to finish their job, the man

leading would silently pass the word along - "Hole in the duckboards",

"Wire overhead", "broken duckboards", etc., and it would

be passed along from man to man till it reached the rear.

Moving along the boards at night, like a spectral army,

while Fritz was "putting them over", is an experience which only

those men who have actually been through it know what it is. It

was a hair-raising experience, and fatigue parties on the Somme

were no joke. It was quite a common saying that "sometimes a

fatigue party came back, and sometimes it didn’t". One night a

sergeant (Begg) came to the mouth of the dugout and called out,

"Any of No. 16 Platoon down there?" As there was not, he was told

so. "Brigade machine-gunners" was the answer; but not being

satisfied he came down and grabbed all the men he could see (after

the "I want four volunteers, you, you, and you!" style) for a

midnight fatigue. The men had returned only a little while

before. The job to be done was to go back to headquarters, and

carry somestuff that the colonel had ordered to be taken to the

front line. Failing to find the duckboard track. . . . . . .he led the

men through the mud to H.Q. The party consisted of twelve men.

When the "stuff" was collected it turned out to be a few primus

stoves and some bottles of kerosene. The beauty of it all was

that the sergeant made all the men go forward, amidst the shell-fire,

though many of them were carrying nothing, and the track

from Rose Trench to Miller Son Dump was a veritable death trap,

as the dead men lying around fully testified. . . . . . . .Next morning

he got it in the neck. . . for taking the wrong fatigue party out.

On the 26th of November the battalion came back to Cow

Trench. After being relieved in the line it was customary for the

men in the posts to go back independently to an appointed place

where they all would meet again. This was a grand idea and no

doubt saved many casualties. . . . . .

Deb Parkinson

Deb ParkinsonThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.