Charles E W Bean, Diaries, AWM38 3DRL 606/245/1 - 1915 - 1925 - Part 12

16.

road, or else go out to the through the C.T. to the front line and

approach the gunpit in the same manner as I approached this one. I

chose the road. The officer informed me that I was perfectly safe as

long as I did not stand upright. Not being able to propel myself along

as I did in the C.T. by putting my hands and elbows into the sides, I

had a frightful time. Having to bend, I found my belly on the slush

most of the time. I lost my puttees, and with difficulty hung on to

my boots and pants. All the occupants of these posts dreaded, the

journey out almost as much as the dreaded the thoughts of the gunpits.

In places along the front line hand pumps were installed, and these

were the only places it was possible to walk about. The rest of the

trenches were nothing less than a nightmare. Of course during the

night movement was over the top, and the conditions were much better

though far from pleasant. By the time the corporal and myself reached

home again, we were a sorry pair of mortals to gaze upon.

The day of the relief came round, and Lt. Joe Mackay informed me

that he would take two sections of the bombers and occupy the gunpits,

and I was to stay at Battalion HQ with two sections and attend to

rations, fatigues, etc. I would relieve him after three days with my

sections. However, when the three days were up, they liked the gunpits

better than our jobs and pozzies, and insisted on doing the full week

in the posts. After dinner, wrapped up in our sheepskins and gear, we

moved off. Having reached Bn HQ where my party had to make their

homes, Lt. Jose Mackay marched his two sections off to the front lines.

My first duty was to see that the evening meal was forthcoming, and

handing over my charge to Sgt. Drummond, a junior sergeant, I hurriedly

went off to the village of Flers, where all the battalion cooks were

located. The day was closing in, and a sleeting rain drove into my face

as I hurried along. Coming to the village pond, I found three dead

horses which were slowing stinking their way into the atmosphere. Two

Hun shells arrived at the same time, throwing brickbats, sticks, etc

in my vicinity. I ran behind a portion of a house still standing, to

await the passing of the iron storm. I found I was not alone. Two dead

men lay sprawled alongside me, and it was a toss up which stank the

17.

most, men or horses. I have heard men argue in all sincerity that they

could distinguish and classify the different stinks. Some vowed they

could tell the difference between English and German dead. When

things quietened down I raced up the main street of the village. Some

houses and shops were flattened, others still resembled houses and odd

men were residing in some of the cellars. The portion of the village

allotted to our cooks was deserted, and where they had settled down

was for me to find out. A gun crew of 18 pounders were busy dragging

their gun into one of the Frenchies bedrooms. They were pushing the

barrel through the wid window as I left them. They knew nothing of my

cooks. Up and down streets and lanes in the blinding sleet, running

to cover occasionally, as German hate descended on the village, I found

darkness upon me and no cooks. I was furious. Realising I was on a

hopeless job, I turned back to BN HQ. In an out of the way lane, I

heard voices coming out of the earth singing the hymn "The Church has

one foundation". Hunting round to find these pious souls, I came upon

them in a large cellar. Here were my two cooks, seated with a demijohn

of rum between them and singing lustily the parody of the well known

hymn -

We are the Aussie Army,

The A. N. Z. A. C.

We cannot shoot, we won't salute

What earthly use are we?

And when we get to Berlin

The Kaiser, he will say

Hoch! Hoch! Mein Got, what a bloody rotten lotAr To pay six bob a day.

The sight of my infuriated face quelled the singing. In language

in keeping with the weather, I had them thoroughly convinced that lines

four and six, seven, and eight were composed chiefly for their benefit.

However, with the help of four other cooks who were doing their best

under difficulties, we eventually had the food cooked and sent off to

the front line. It must have been about 10 p.m. before the men

received their evening meal.

When I eventually reached my xxx own men at Battalion HQ I found

them damp, cold, miserable, and peevish. However, after the meal they

were considerably comforted, but not for long. The short time at their

disposal to build homes for themselves in Bull Run Trench found darkness

18.

upon them and no homes. There was nothing else to do but sit huddled

up under bits of boards etc., and wait for daylight. The conditions

were appalling. Clothes damp and sodden, feet cold and swollen, boots

resembling wet brown paper. Our spirits were in keeping with the

conditions, and were as low as it was possible for them to get. Feet

were our greatest problem; trench feet were sending an endless stream

of men to the hospitals. Each of us carried a small tin of fat with

which we were expected to rub our feet twice a day.

Battalion HQ was well known to the Huns, and of course received

its issue of ironmongery in keeping with its importance. Some of the

men were spending the night about 100 yards along the trench, and on

account of several shells bursting near them, came down to where I was

crouched under some boards. They were no better off. Shells pelted us

with clods and they were for moving again. Seeing me sit back and

endeavour to doze, they were reassured. By their remarks, I gathered

that they thought I was a hero. They did not realise that I was a

bigger coward than they. I had just about reached the depth of human

misery and did not care one jot if a shell had landed on me.

When daylight came at last I went across to see my cooks. With

thick heads and mouths like drain pipes, they were manfully trying to

retrieve their good name. Breakfast over, I sent everyone off to Flers

to gather boards etc. to get some cover from the weather. Knowing that

the rest of the bombing platoon were in ddep dugouts, I determined tosaty stay with my half of the platoon and get all under cover before

night came on. At night time our job was finished. We had all dug

square gaps into the side of the trench, and covered the top with

boards, bags, or whatever we could find in the village. I designed

them to hold four men, the idea being that each would keep the others

warm, and that night was spent in comfort compared with the previous

one. Being able to relax ourselves and get our minds off our misery,

our attention was soon drawn to a minor discomfort. Everything and

everyone seemed just as lousy as it was possible to be, but our attitude

towards lice had changed. They only made us dig and scratch the harder.

The following morning I went up to see how the two sections in the gun-pits

19.

were faring. The sentry over the dugouts cursed me for coming

into the pits. It appeared that the Hun, who saw right into the pits,

sent a whizzbang after every visitor who came in sight. As the sentry

stood glued to the edge of the pit and also shared the excitement, it

was not to be wondered at that he was not "at home" to visitors. I

found that all in the dugouts were very pleased with their lot.

Going back, the thoughts of the mud sickened me, and I decided to

gallop over the top, and gallop I did. By the way the Huns pelted me

with bullets I came to the conclusion that I was a very important

personage in the army, and I jumped back intonthe C.T. before I reached

the point I intended. On reaching my bivvy I sat down and like a dog

licking his sores I commenced scraping the slime and mud from my

clothes. Before I had finished I saw a figure coming from the front

line without with only a tin hat and a shirt on. As he gingerly picked

his way along in his bare feet, the tail of his shirt thickened stiff

with slime, gently fanned his tail. Several of us could not keep from

laughing, and this annoyed the poor wretch so much that he said: "Do

you think you are at the bloody zoo? Hop out, any of you -------".

Rarely have it I seen a man so fed up with everything.

The next morning a runner came from the CO and informed me that

he wanted me. On reporting, Colonel Dare told me to sit down and he

would give me my instructions in a minute or two. Without any telling

I knew at once that my lot was to take my bombers, struggle through

and over the dead, and bomb those Huns out of the vicinity of the gun

pits, incidentally leaving many of our bodies to rot and stink along

with the rest. Presently a runner came in and deliavered a message

and went out. Colonel Dare read it, turned to me, and said: "You can

go, I will not need you now." Outside in the fresh air again, I heard

a rattle of machine-guns in the air, and looking up intoma bleak,

wintry sky, I saw an aeroplane part company with one of its wings, and

start slowly tumbling towards the earth. A runner standing nearby

said: "My God, what a day to die." For some reason or other most men

had a horrorof getting cracked on a cold miserable day. The sight of

white faced silent figures being carried past on stretchers appeared

to me to be about the last thing in misery. Strange to say, getting

wounded was not always a miserable business. On one occasion I

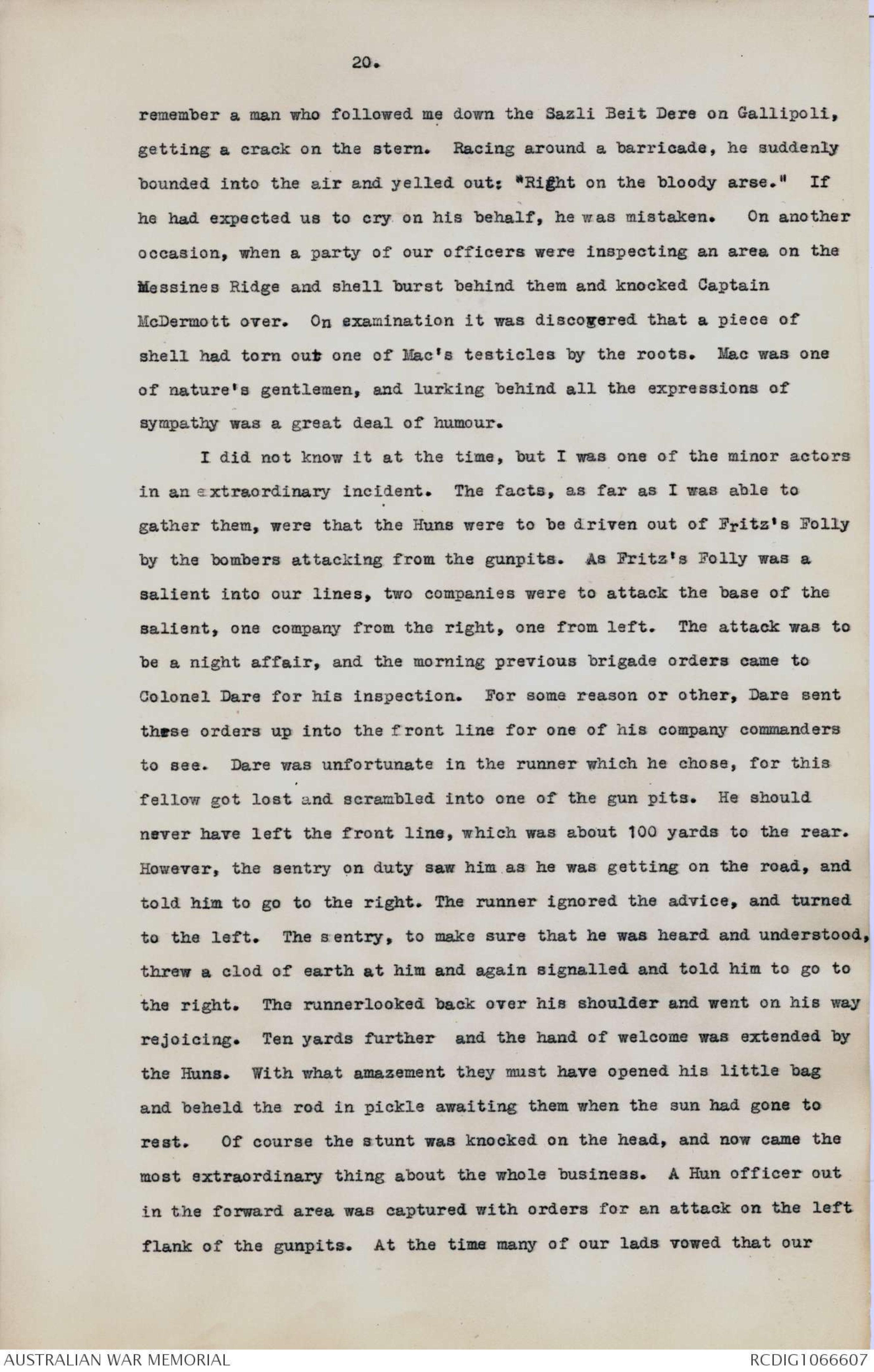

20.

remember a man who followed me down the Sazli Beit Dere on Gallipoli,

getting a crack on the stern. Racing around a barricade, he suddenly

bounded into the air and yelled out: "Right on the bloody arse." If

he had expected us to cry on his behalf, he was mistaken. On another

occasion, when a party of our officers were inspecting an area on the

Messines Ridge and shell burst behind them and knocked Captain

McDermott over. On examination it was discovered that a piece of

shell had torn out one of Mac's testicles by the roots. Mac was one

of nature's gentlemen, and lurking behind all the expressions of

sympathy was a great deal of humour.

I did not know it at the time, but I was one of the minor actors

in an extraordinary incident. The facts, as far as I was able to

gather them, were that the Huns were to be driven out of Fritz's Folly

by the bombers attacking from the gunpits. As Fritz's Folly was a

salient into our lines, two companies were to attack the base of the

salient, one company from the right, one from left. The attack was to

be a night affair, and the morning previous brigade orders came to

Colonel Dare for his inspection. For some reason or other, Dare sent

these orders up into the front line for one of his company commanders

to see. Dare was unfortunate in the runner which he chose, for this

fellow got lost and scrambled into one of the gun pits. He should

never have left the front line, which was about 100 yards to the rear.

However, the sentry on duty saw him as he was getting on the road, and

told him to go to the right. The runner ignored the advice, and turned

to the left. The sentry, to make sure that he was heard and understood,

threw a clod of earth at him and again signalled and told him to go to

the right. The runnerlooked back over his shoulder and went on his way

rejoicing. Ten yards further, and the hand of welcome was extended by

the Huns. With what amazement they must have opened his little bag

and beheld the rod in pickle awaiting them when the sun had gone to

rest. Of course the stunt was knocked on the head, and now came the

most extraordinary thing about the whole business. A Hun officer out

in the forward area was captured with orders for an attack on the left

flank of the gunpits. At the time many of our lads vowed that our

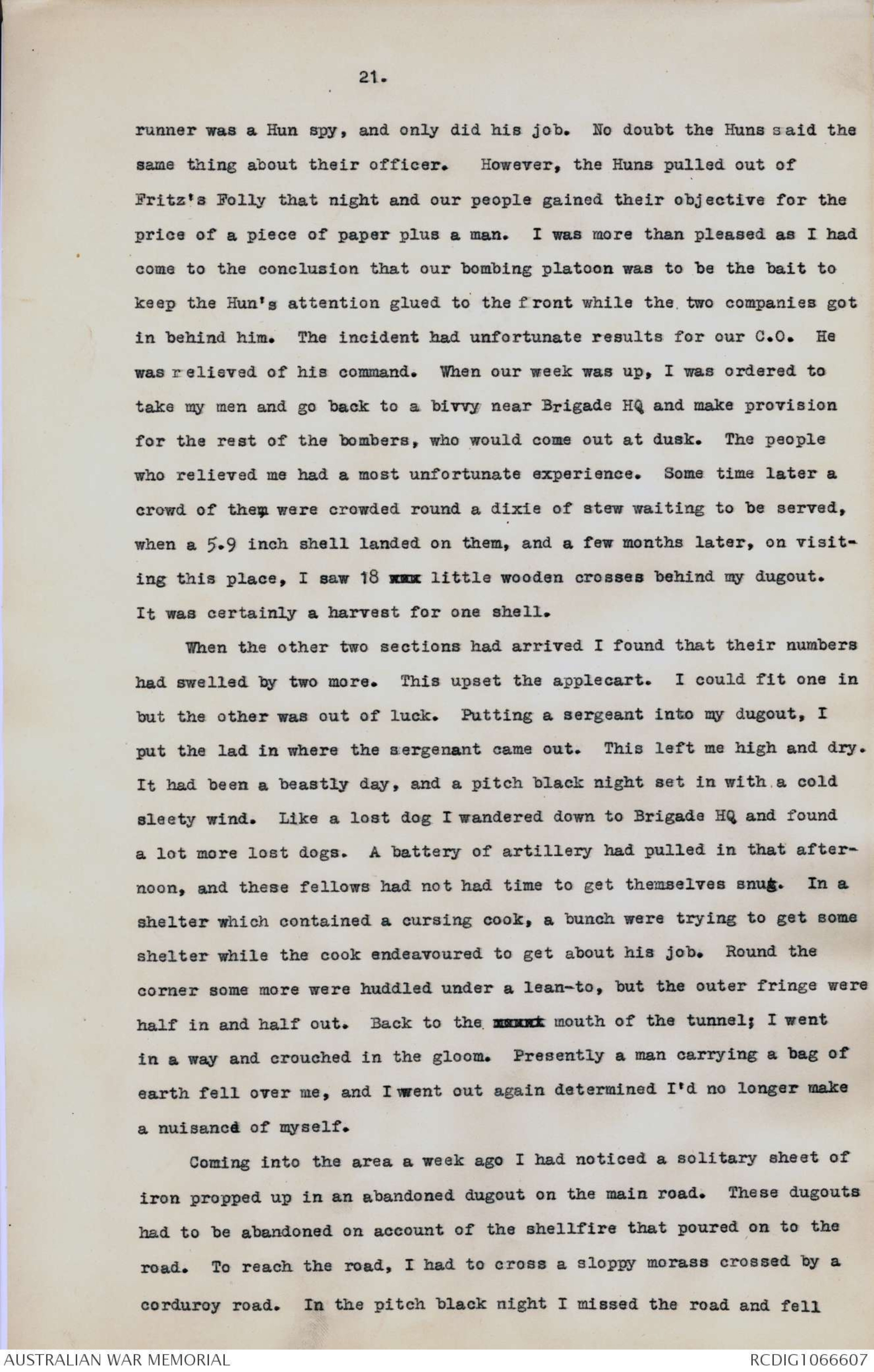

21.

runner was a Hun spy, and only did his job. No doubt the Huns said the

same thing about their officer. However, the Huns pulled out of

Fritz's Folly that night and our people gained their objective for the

price of a piece of paper plus a man. I was more than pleased as I had

come to the conclusion that our bombing platoon was to be the bait to

keep the Hun's attention glued to the front while the two companies got

in behind him. The incident had unfortunate results for our C.O. He

was relieved of his command. When our week was up, I was ordered to

take my men and go back to a bivvy near Brigade HQ and make provision

for the rest of the bombers, who would come out at dusk. The people

who relieved me had a most unfortunate experience. Some time later a

crowd of them were crowded round a dixie of stew waiting to be served,

when a 5.9 inch shell landed on them, and a few months later, on visiting

this place, I saw 18 xxx little wooden crosses behind my dugout.

It was certainly a harvest for one shell.

When the other two sections had arrived I found that their numbers

had swelled by two more. This upset the applecart. I could fit one in

but the other was out of luck. Putting a sergeant into my dugout, I

put the lad in where the sergenant came out. This left me high and dry.

It had been a beastly day, and a pitch black night set in with a cold

sleety wind. Like a lost dog I wandered down to Brigade HQ and found

a lot more lost dogs. A battery of artillery had pulled in that afternoon,

and these fellows had not had time to get themselves snug. In a

shelter which contained a cursing cook, a bunch were trying to get some

shelter while the cook endeavoured to get about his job. Round the

corner some more were huddled under a lean-to, but the outer fringe were

half in and half out. Back to the xxxxx mouth of the tunnel; I went

in a way and crouched in the gloom. Presently a man carrying a bag of

earth fell over me, and I went out again determined I'd no longer make

a nuisance of myself.

Coming into the area a week ago I had noticed a solitary sheet of

iron propped up in an abandoned dugout on the main road. These dugouts

had to be abandoned on account of the shellfire that poured on to the

road. To reach the road, I had to cross a sloppy morass crossed by a

corduroy road. In the pitch black night I missed the road and fell

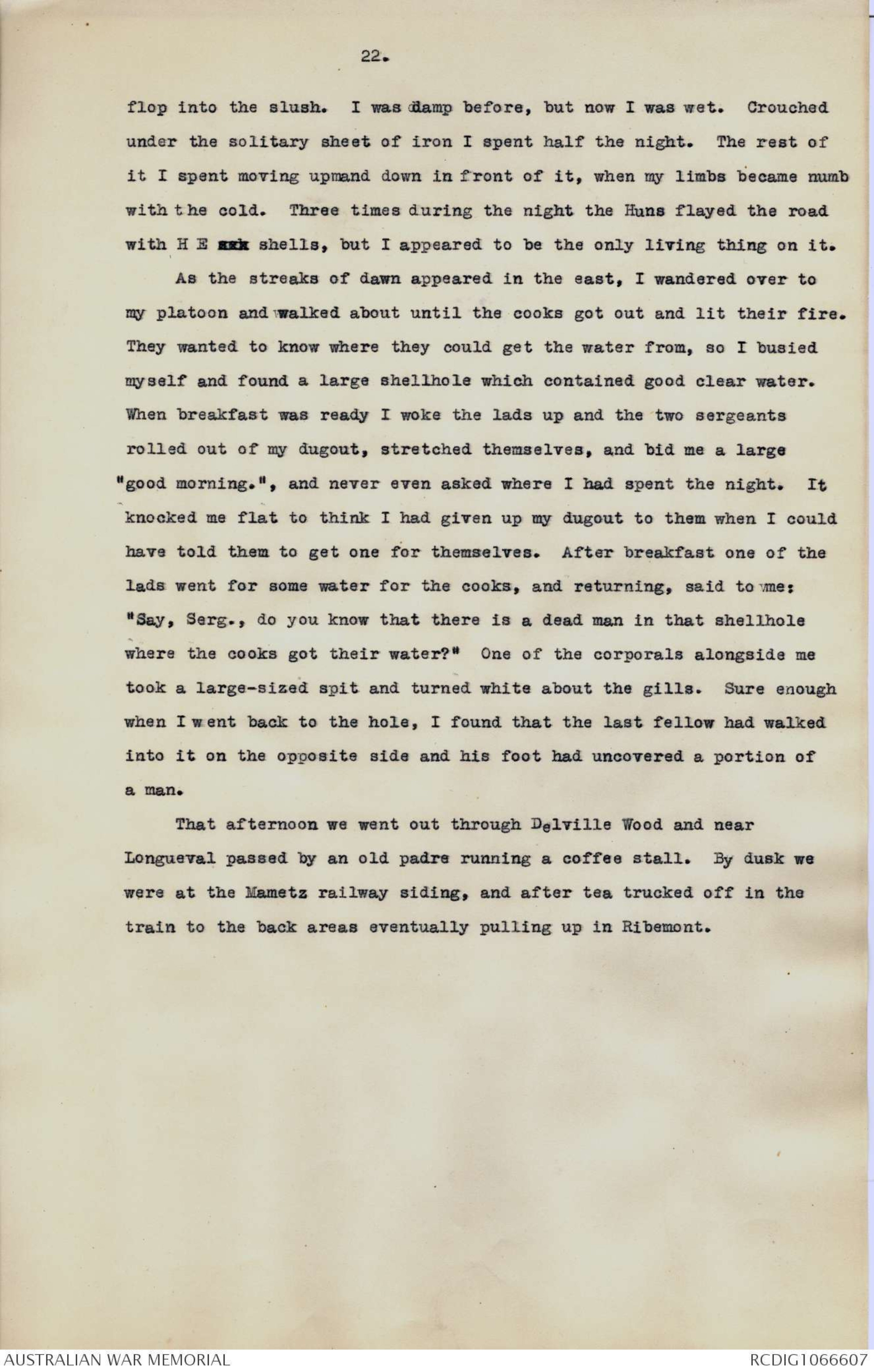

22.

flop into the slush. I was damp before, but now I was wet. Crouched

under the solitary sheet of iron I spent half the night. The rest of

it I spent moving upmand down in front of it, when my limbs became numb

with the cold. Three times during the night the Huns flayed the road

with H E xxx shells, but I appeared to be the only living thing on it.

As the streaks of dawn appeared in the east, I wandered over to

my platoon and walked about until the cooks got out and lit their fire.

They wanted to know where they could get the water from, so I busied

myself and found a large shellhole which contained good clear water.

When breakfast was ready I woke the lads up and the two sergeants

rolled out of my dugout, stretched themselves, and bid me a large

"good morning.", and never even asked where I had spent the night. It

knocked me flat to think I had given up my dugout to them when I could

have told them to get one for themselves. After breakfast one of the

lads went for some water for the cooks, and returning, said to me:

"Say, Serg., do you know that there is a dead man in that shellhole

where the cooks got their water?" One of the corporals alongside me

took a large-sized spit and turned white about the gills. Sure enough

when I went back to the hole, I found that the last fellow had walked

into it on the opposite side and his foot had uncovered a portion of

a man.

That afternoon we went out through Delville Wood and near

Longueval passed by an old padre running a coffee stall. By dusk we

were at the Mametz railway siding, and after tea trucked off in the

train to the back areas eventually pulling up in Ribemont.

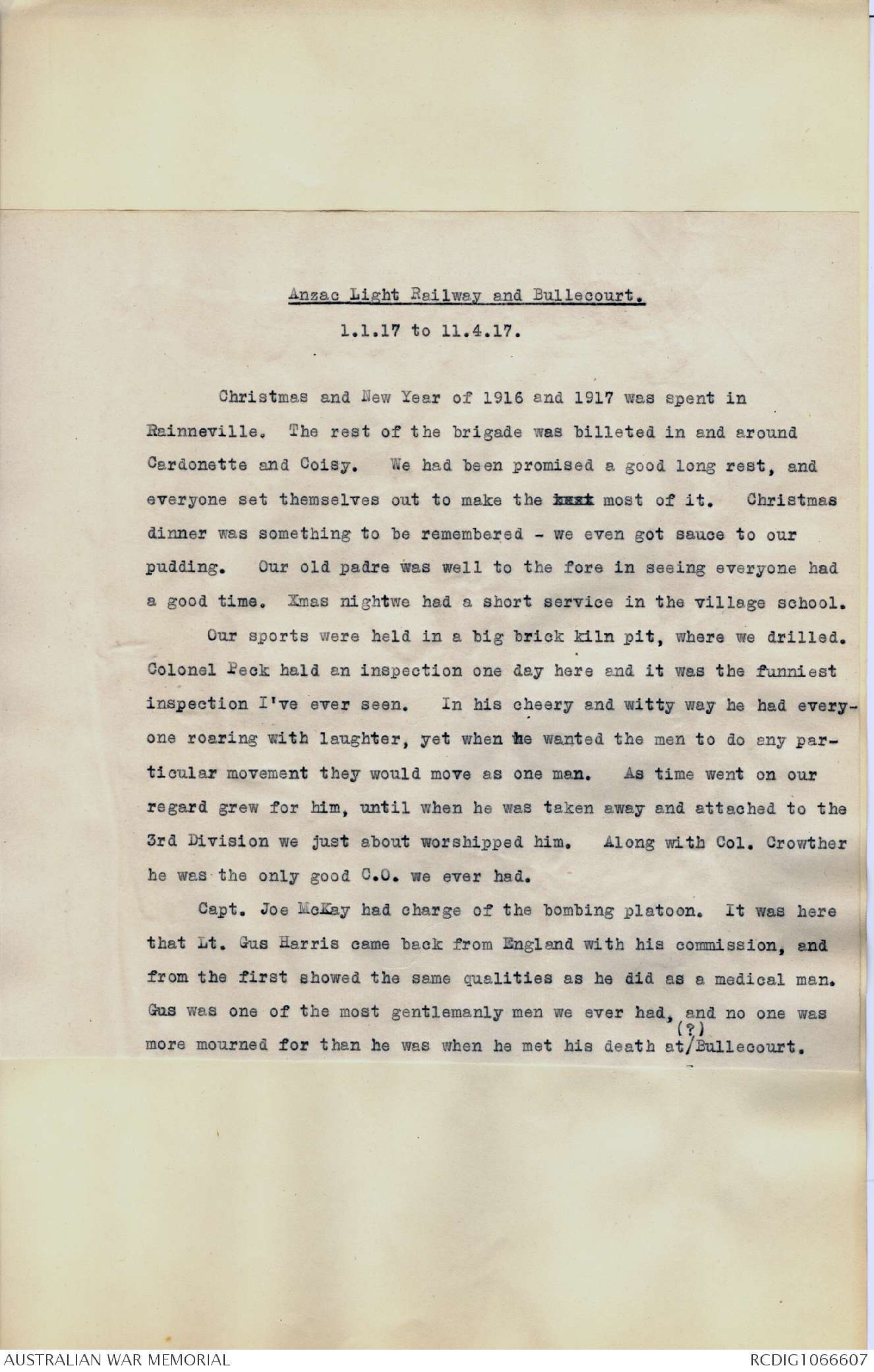

Anzac Light Railway and Bullecourt.

1.1.17 to 11.4.17.

Christmas and New Year of 1916 and 1917 was spent in

Rainneville. The rest of the brigade was billeted in and around

Cardonette and Coisy. We had been promised a good long rest, and

everyone set themselves out to make the best most of it. Christmas

dinner was something to be remembered - we even got sauce to our

pudding. Our old padre was well to the fore in seeing everyone had

a good time. Xmas nightwe had a short service in the village school.

Our sports were held in a big brick kiln pit, where we drilled.

Colonel Peck hald an inspection one day here and it was the funniest

inspection I've ever seen. In his cheery and witty way he had everyone

roaring with laughter, yet when he wanted the men to do any particular

movement they would move as one man. As time went on our

regard grew for him, until when he was taken away and attached to the

3rd Division we just about worshipped him. Along with Col. Crowther

he was the only good C.O. we ever had.

Capt. Joe McKay had charge of the bombing platoon. It was here

that Lt. Gus Harris came back from England with his commission, and

from the first showed the same qualities as he did as a medical man.

Gus was one of the most gentlemanly men we ever had, and no one was

more mourned for than he was when he met his death at ^(?) Bullecourt.

The evening of Boxing Day was wet, cold, and miserable, and

everyone was confined to their billets. Four or five of the officers,

Schultz, Hawkins, and a few more of the hard-case variety, found

themselves lodged in an estaminet. The order of the day was "Oh,

landlord, fill the flowing bowl.", and everyone was happy.

To see what was on orders for the following day, I had occasion to

hunt around to find my officer. On going to this particular estaminet

I noticed that the occupants conduct lent itself more to comfort than

propriety. The following day I was let into the secret. It appeared

that, as the evening wore on and the wine disappeared, the journeys to

the rear of the establishment became very disagreeable on account of

the sleet and rain. The old French lady noticed the difficulties of

her guests, and promptly went to her boudoir and brought forth a piece

of the household chinaware. This, she insisted on handing round to

each in turn. Those who appeared at all bashful were assisted by the

old lady shouting "Wee Wee Monsieur, Wee Wee." "Gentlemen by Act of

Parliament" was indeed a farseeing piece of legislature.

Next morning, Boxing Day, I was warned to move out along with

four others to go and work on the Light Railway. Previous to this

they had asked for men who had railway experience, and I decided to

swing the lead for awhile. Ever since coming out of the line at

Flers I'd just about dropped my bundle, and I've never been so downhearted

or weary before or since. It's the only time I've ever left

the battalion deliberately, and even then I was only away for a month

and I became homesick and used to try to get back at every opportunity.

Every battalion in the 4th Div. were sending five men, the total

amounting to 60, and I was the only N.C.O. We were marched over to

Villers Bocage, when the 4th Brigade and the 12th Brigade men were put

in busses and taken to Meaulte. Here we waited until evening and then

were put in a train and taken up to Quarry Siding, not very far from

40.

Bernafay Siding. We spent the night in some huts and next morning

were roused out very early to go to work. We were issued with

48 hours' rations before we left our battalions, which is the usual

thing, and therefore we had nothing to eat for breakfast and all

this day but hard biscuits. The weather was bitterly cold and the

mud was even worse than the cold. A guide took us up to "C" Coy.

of the ^4th Pioneers, and we were attached to them for work and rations.

Capt. Jock Orr was in charge of the coy., and he told us to

hunt around and find a home for ourselves. There was one deep Hun

dugout, and only a few were able to get into it as the Pioneers were

in it themselves. There was not another place big enough to hold a

rabbit and not a stick or sheet of iron to build anything with. I

brought this to Jock Orr's notice, and he gave each man one sheet of

iron and told them that he would give them until dinner time to get

a home together. After dinner they were to go to work.

It would be utterly impossible for me to describe the desolation

of our surroundings. We were in the middle of a village called

Longueval. There was hardly a whole brick in the place, let alone

timber and iron. Every water hole was a sheet of ice, and by what

I remember hardly a day passed without it either raining or snowing.

When dinner time came, very little had been done, and after a

lot of fuming old Jock consented to let the men have the rest of the

short day to make themselves comfortable. The boys were working

after darkness had set in, and then not one dugout out of the lot

was fit to live in. They had pulled together, three or four to a

party, dug a hole wide enough and long enough for their four sheets

of iron, and then with a few sticks make a roof. There was just

about three feet between the floor and the roof, and, as the place

was flat and the boys had not time to dig drains,the rain during

the night just poured in and flooded nearly everyone. If anyone

can tell me how to spend a more miserable night than this, I'd like

to hear it.

In the morning, very few were dry all over and very few had

had a sleep. All they had for breakfast was a cup of tea, a tiny

piece of bacon - which the Pioneers wacked up with them - and hard

Deb Parkinson

Deb ParkinsonThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.