Charles E W Bean, Diaries, AWM38 3DRL 606/244/1 - 1916 - 1933 - Part 26

CONTENTS.

PART 1.–TACTICAL.

A.–PRELUDE TO THE BATTLE.

B.–OBJECT AND ARRANGEMENT OF THE LESSONS LEARN

C.–HIGHER COMMAND; EXPERIENCES AND LESSONS

D.–INFANTRY AND MACHINE GUNS

I.— Causes of initial failures

II.—Measures by which a gradual improvement was attained

III.— Experiences and lessons

(a). General

(b) Training

(c). Reliefs

(d). Distribution

(e). Construction of positions

(f). Defence

(g). Immediate and methodical counter-attacks

(h). Equipment ..

(i). Supply

E.– PIONEERS, SEARCHLIGHTS, "FLAMMENVERFER" AND TRENCH

MORTARS

F.–ARTILLLERY

I.—Causes of initial failures

II.—Measures by which a gradual improvement was attained

III.— Experience and lessons..

...

(a). Preparations for the battle..

(b) Command

(c). Training

(d). Organization.

(e). Construction of battery positions

(f). Fire control .

(g). Fire activity..

(h). Attacks and counter-attacks

(i). Close defence

(k). Ammunition and material..

G.—COMMUNICATIONS AND RECONNAISSANCE

I.—Causes of initial failures

II.—Measures by which a gradual improvement was attained

Increase of the means of communication..

III.—Experience and lessons.

(a). Employment..

(b). Organization .... ...

(c). Preparations on quiet fronts ... ...

AND ANTIAIRCRAFT

H.—THE FIGHTING TASKS OF AEROPLANE AN ANTI-AIRCRAFT

ARTILLERY ... ...

I.—Causes of initial faIlures ... ...

II.—Measures by which a gradual improvement was attained ...

III.—Experiences and lessons ... ... ...

I.—EFFECTS OF GAS AND PROTECTION AGAINST GAS ... ...

Experiences and lessons

—————

APPENDIX.

—————

PREPARATORY MEASURES BEFORE THE ENGAGEMENT OF A

DIVISION IN A DEFENSIVE BATTLE ... ... ... ...

A.Divisional staff. ...

B.—Troops ... ...

I.— Infantry ...

II.—Cavalry ...

III.—Artillery ... ...

IV.–"Minenwerfer“ ... ... ...

V.—Pioneers ... ...

VI.—Divisional telephone detachment ... ...

EXPERIENCE OF THE GERMAN 1ST ARMY IN

THE SOMME BATTLE.

24th JUNE—26th NOVEMBER, 1916.

PART 1. TACTICAL.

First Army H.O.

Ia /2122. Secret.

30th January, 1917.

A. PRELUDE TO THE BATTLE.

1. The Somme battle did not come as a surprise to the Second Army, which, from the 19th July

1916, onwards, was divided into the First and Second Armies. As early as February, 1916, our aeroplanes

reported the construction of numerous new hutments in front of the northern wing of the Army on both

sides of the Ancre. Shortly afterwards, an increase in the number of divisions on the English front north

of the Somme took place. As a result of successful raids and patrol work, we learnt that these divisions

were relieved successively after a few weeks in line. Towards the end of April, the number of English

divisions north of the Somme had already increased to 12, opposed to only 4 German divisions.

The plan which was formed at that time of meeting the enemy's expected offensive north of the Somme

by a counteroffensive could not be carried out owing to lack of sufficient forces. In April, one division

was placed at the disposal of the Army as a reinforcement. This division was put into line north of the

River Ancre where the English line was most strongly held. Thus, on the right wing of the Army, each

division held an average front of 6 kilometres, while on the rest of the Army front the divisional sectors

amounted to 7½-9 kilometres

In May, 2 divisions were withdrawn from the front of the Second Army and replaced by one division

which, during its short period of rest, had not yet been able to replace the losses which it had suffered at

Verdun. In addition to this, a considerable number of heavy batteries equipped with modern German

guns were replaced by batteries of captured guns.

Up to May, it was not considered probable that the French would co-operate in the expected attack.

At the beginning of June, the signs of an approaching attack became more evident. Just north of

the Somme, 2 French divisions took over the sector previously held by the English. The conclusion at

first drawn that this measure had a defensive object with a view to giving greater depth to the English

offensive mounted further north, was rejected as soon as the specially good 20th French Corps, known as

a "Gladiator Corps," was identified by raids north of the Somme. South of the Somme, also, preparations

for a hostile attack became more and more apparent, so that, during the course of June, the supposed frontage

of the enemy's offensive was fairly clearly established as extending from the neighbourhood of Gommecourt,

on the north, to the neighbourhood of the Roman road about 8 kilometres south of the Somme, on the south.

In June, one division and the field artillery of another division were placed at the disposal of Army

Headquarters. Towards the end of June, a further reinforcement of 17 light field howitzer batteries was

allotted to the Army

2. On the 22nd June, the enemy's bombardment began to become intense

From the 24th June onwards, the intense bombardment was continuous. This bombardment comprised

a large proportion of artillery of the heaviest calibres and of heavy long range guns.

On the 1st July, about 8 a.m., the great English-French infantry assault took place on a front of 40 kilometres

between Gommecourt and the west of Vermuandovillers, while the artillery bombardment was continued

on a sector which considerably overlapped the zone of attack. The assault penetrated our badly damaged

defensive front at a great many points. North of the Ancre, by the evening of the 2nd July, counter-attacks

were successful in recapturing the whole of our line, and inflicted heavy losses in killed and prisoners on the

English. South of the Ancre also, as far as Thiepval inclusive, the English, who had captured our trenches,

were driven out of them by the evening of the 3rd July. On both sides of the Somme, however, the English

and French had driven a deep wedge into our defensive front. On this sector our losses were so considerable

that there was no available strength with which to carry out the intended counter-attack.

During the following days and weeks, we continued to lose further ground at this broad breach in our

front. The engagement of the reinforcements which flowed in to the Army from all sides had to be effected

in the most unfavourable circumstances. Owing to the overwhelming superiority of the enemy in aircraft,

artillery, ammunition and men, it was only possible to stop the most dangerous gaps which had been made

in the German defensive front. Owing to the force of circumstances, the cohesion of the arriving reinforcements

0had to be broken up in order to avoid the danger of the enemy breaking through.

Under these difficult conditions, the whole organization of the defence had to be constituted anew.

was only after the lapse of long weeks that the defence could be put on equal term with the enemy's

superiority as regards fighting material of every kind.

In spite of this, the enemy has not succeeded in achieving the intended breaking through of our Western

Front. His plans have been shattered by the devoted and untiring courage and loyalty of our Army. Every

man who has fought on the Somme may be proud that he was there, and that the battle, which is so far the

greatest in any war, has, through the failure of the enemy, ended as a German victory.

B. OBJECT AND ARRANGEMENT OF THE LESSONS LEARNT.

3. The numerous lessons learnt from the Somme Battle have already been dealt with and published in

Part 8 of the Chief of the General Staffs instructions for trench warfare entitled "Principles of Command

(11037) Wt. W. 1756--9719. 900. 3/17. D&S. G.2. P.17/341.

4

during a Defensive Battle in Trench Warfare."✼ A thorough acquaintance with these instructions is, therefore,

assumed as a preliminary to studying and understanding the following remarks, which have been

published by the First Army at the desire of the Crown Prince of Bavaria's Group of Armies. In this

memorandum, the “Principles of Command during a Defensive Battle" will only be referred to in so far

as the events on the Somme are concerned; the organization, tactical employment and co-operation of the

different arms will be described in the light of the experience gained during a battle in which the forces

involved have been on a scale hitherto unknown.

The subject matter has been divided up in such a way that in Part I. (Tactical), the different arms are

treated under the following sub-headings:—

(1) The causes of initial failures,

(2) The measures by which a gradual improvement was attained,

(3) Experiences and lessons.

In this way, a picture of the development of all details of the fighting during the battle will be obtained,

which will perhaps be of use to a Commander who may in future find himself engaged in a battle of similar

nature.

Part 2 deals with all questions connected with administration and interior economy.

C. HIGHER COMMAND; EXPERIENCES AND LESSONS.

4. Before the beginning of the Somme battle, the Headquarters of the Second Army, as then constituted

had grouped the five divisions north of the Somme and the four divisions south of the Somme under the two

Corps Staffs which were available in the area, in order to obtain a uniform system of command throughout

The battle frontage of the two Corps, thus constituted, amounted to 22 miles

the anticipated zone of attack.

north of the river and 20 miles south of the river. The initial attack by the enemy astride the river, and

the consequent re-entrant created in our line, increased these frontages considerably. The divisions sent up

as reinforcements by the Supreme Army Command were only accompanied very gradually by fresh Corps

Staffs, and these Staffs were totally unacquainted with the Somme battle front. Their entry into line did

indeed reduce the frontages held by formations, but the Commanders had to become acquainted with the

ground before they could carry out their tasks

The ever increasing size of the Second Army prompted the Higher Command to reorganize the troops

engaged on the battle front in the First and Second Armies. This change took effect from the 19th July.

The First Army took over approximately the same battle front as had been previously held by the northern

Corps of the Second Army. This sector was gradually divided up between five Groups each under a Corps

Headquarters, each Group commanding two or four divisions.

It was not till the 1st October that the new First Army was given a separate Lines of Communication

Headquarters. Until then its administration was effected by the Lines of Communication Headquarters of

the Second Army.

5. The difficulties of command which arose from the constant change of sectors and staffs were very

considerable, and were still further increased by the frequent shifting of headquarters rendered necessary

by the loss of ground; this had a most deleterious effect on the smooth running of telephonic communication.

A rigid system of command, equal to all demands, could not be thoroughly established until the organization

of the Army was placed on a clear and permanent basis; unity of command was then attained by retaining

more or less permanent Corps Staffs in sectors

Itis evident that an Army which is subject during a battle to constant changes of command is, especially

when acting on the defensive, at a very great disadvantage as compared with an attacking enemy whose

organization has been thoroughly planned with a view to carrying out his designs. As far as possible, therefore,

efforts must be made, whenever a hostile offensive on a large scale is anticipated, to organize the system

of command in good time and on so r a basis that the Army and Corps Headquarters can retain command

of their former sectors during the progress of the battle.

6. The lateral boundaries of the battle sectors of Armies, Corps and Divisions are primarily dictated by

the ground, and, above all, by the facilities which they give for the development of artillery fire and for

artillery observation

7. In the heat of the battle, the influence of a well-known commander plays a great part. Acquaintance

with the personality of his subordinates, an appreciation of their abilities, and a right judgment of their

qualities, enable the Higher Commander to make his decisions as regards the employment of his troops at the

decisive points of the fight. This is especially the case as regards the divisional fighting units. It us, therefore,

desirable that Divisional Commanders should change with their divisions.

8. As regards Corp Headquarters, which, during a battle, command a Group of three to four divisions,

itis desirable that they retain command of their own original divisions as far as possible. Within a Group

however, the advantage of fighting under a commander whom one knows is secondary to the consideration that

the command must be on as permanent a footing as possible. This condition can only be attained by allotting

permanent Corps Staffs to sectors.

9. The demands made on the Staffs of Armies, Corps and Divisions by the work and responsibility

entailed in the course of a great battle of long duration are so enormous that the usual number of officers

allotted to Staffs is not sufficient. To every Corps Headquarters a permanent Chief Administrative Staff

Officer was therefore allotted during the battle, principally for duties of supply, and also a permanent General

Staff Officer; each division was allotted a second (permanent) General Staff Officer. Corps and divisions were

also allotted permanent Pioneer and Communication Officers, while, in addition to the above, permanent

Wing Commanders, Anti-aircraft Officers and Wireless Officers were allotted to Corps Headquarters.

The number of orderly officers, also, required to be increased in order to provide the personnel for visiting

the trenches (a procedure which demanded much time) and for keeping personal touch with the subordinate

commanders, as well as to convey to the Higher Commanders a picture of the events of the battle independently

of the reports received from the troops.

10. It is of much importance to make new formations acquainted in good time with the battle situation.

Officers must, therefore, be sent ahead at once to gain touch with every new Corps and division

arriving.

Besides the above, during the last weeks of the battle, Army Headquarters sent a copy of all orders

dealing with general principles to the Staffs of formations which were earmarked for future inclusion in the

———————————

✼ This is being issued separately.— G.S. + Part 2 has not yet been received.— G.S.

5

Army, through the medium of their old formations. The Higher Commanders, as they arrived, were then

interviewed personally by the Commander-in-Chief or by the Army Commander; the importance and nature

of the Somme battle was explained to them, and they were also made acquainted with the features of the

ground in their future sectors, and with the instructions and general principles already issued by the Army

for the battle. General Staff Officers, Artillery Commanders and Pioneer Commanders of the relieving Corps

and divisions worked for several days, prior to the arrival of their own formations, with the Staffs of the

formations to be relieved; these latter formations, in turn, left part of their Staffs behind for several days

after the relief.

11. It is of great importance for the execution of the command during a battle that the Higher

Commanders should obtain a rapid knowledge of the progress of events which are taking place in front. This

knowledge often forms the only basis for sending forward and putting in reserves at the night moment. Army

Headquarters have, with this object, organized in each Group sector special Army Observation Posts.

similar organization was formed in all Corps and divisions. A special artillery system of telephonic communication

connected to the Headquarters of the General Officer Commanding Artillery has frequently provided

the most valuable rapid pictures of the situation.

12. In their conduct of the battle, Army and Corps Headquarters must, in addition to issuing strict

orders as regards defensive work, confine themselves principally to ensuring clear and well-defined relations

in the grouping of the troops and in the holding in readiness of reserves behind dangerous points. Both the

Commander-in-Chief and the Army Commanders will obtain the best foundations for their decisions by

keeping constantly in personal touch with the Commanders of the troops. Verbal discussions are of considerably more value than telephonic conversations. During the Somme battle the Commander-in-Chief, in

company with the Army Commander, visited almost daily three or four Divisional Commanders at their

headquarters or their battle-stations. These interviews, at which the Group Commanders were usually

present, were of great advantage to the unity of control in the battle, and to the co-operation of all arms.

This procedure was of particular value at moments when the situation was rapidly changing. After such

conferences, Army Orders and Corps Orders were frequently dictated at Divisional Headquarters and

forwarded to the units concerned by telephone.

13. The real weight of the fighting rests on the shoulders of the Divisional Commanders, on whom

devolves full responsibility for the maintenance of their sectors. Divisional Commanders must, therefore

be given control of all the organs of action available in their sectors, with the exception of guns employed

on special tasks and. in exceptional cases, Corps Artillery Groups detailed for special long-range objectives.

They must at the right time allot to their subordinate commanders both their own reserves and the reserves

placed at their disposal by superior authority; these subordinate commanders must, in their turn, make

local arrangements for the employment of these reserves on the battlefield.

The Divisional Commander must exert a continuous and keen influence on the whole control of the

action; this will be ensured by accurate reconnaissances on the ground, and by maintaining daily persona!

touch with his troops and their commanders.

14. Every Higher Commander must clearly recognise that every report from front to rear and every

order from rear to front requires a very long time to reach its destination. During a defensive battle, the

fighting zone lies almost continuously under the enemy's intense artillery

bombardment. It has been

frequently found that orders take 8 to 10 hours to reach the front line Divisional Headquarters. It

has often proved of value to forward orders to reserves by staff officers in motor cars.

been accurate and up-to-date maps

15. To carry out a well-ordered relief, it is of great importance that accurate and up-to-date

maps

and plans are handed over. These maps must show not only the details of the actual front and the

distribution of the fighting material available, but must also include the area in rear (billeting facilities,

condition of the roads and administrative arrangements). It is desirable that the arrangements for these

maps should be controlled by the General Staff Officers allotted permanently to sectors.

D. INFANTRY AND MACHINE GUNS.

1. Causes of initial failures.

16. The reasons for our previous failures arose not so much in the domain of purely infantry

considerations, as from our inability at the outset to make equivalent reply to the enemy's concentrations,

more especially of aircraft and artillery.

At the commencement of the battle, telephone lines, which worked perfectly well in quiet times, were

at once cut, and only a small supply of apparatus for visual signalling and wireless was available. The

transmission of information was consequently faulty and resulted frequently in the total isolation of the

Higher Command and in the absence of all co-operation between the various arms.

The infantry, heavily engaged, were often left to their own devices for hours and days at a time, or

else the front line trenches would be crammed with troops owing to the ignorance of the situation that

prevailed in rear. This entailed unnecessary casualties and the moral effect was bad. This state of affairs

was aggravated by the enemy's superiority in the air, which at first was incontestable. Not only did the

enemy's airmen direct the artillery fire undisturbed, but by day and by night they harassed our infantry with

bombs and machine guns, in their trenches and shell holes, as well as on the march to and from the trenches

Even although the losses thus caused were comparatively small, their occurrence had an extremely lowering

effect on the moral of the troops, who at frst were helpless. The innumerable balloons, hanging like grapes

in clusters over the enemy's lines, produced a similar effect, for the troops thought that individual men

and machine guns could be picked up and watched by them and subjected to fire with observation

17. On long stretches of front, the small forces which were at first available were not distributed

sufficiently in depth. The consequent feeling of uncertainty experienced by commanders led them not

infrequently, in their determination to hold the front line at all costs, to reinforce the front line prematurely,

frequently found that orders take 8 to 10 hours to reach the front line from Divisional Headquarters. It

has often proved of value to forward orders to reserves by staff officers in motor cars.

15. To carry out a well-ordered relief, it is of great importance that accurate and up-to-date maps

and plans are handed over. These maps must show not only the details of the actual front and the

distribution of the fighting material available, but must also include the area in rear (billeting facilities,

condition of the roads and administrative arrangements). It is desirable that the arrangements for these

to crowd it unnecessarily, and, on the other hand, to leave the rearward trenches unoccupied.

This failure to distribute the infantry in depth went hand in hand with a trench system of insufficient

depth, a scarcity of serviceable positions in rear and a shortage of labour.

The impossibility of regularly reliefs made it necessary to overtax the strength of the infantry.

The first reinforcements to dribble in could only fill the largest gaps. Even the infantry of freshly

assigned divisions had to be thrown into the fight under by unit, as soon as each arrived, or else were pushed

up to take over in too great a hurry from utterly exhausted troops. The consequence was that portions

of the positions were not infrequently lost.

A 3

11057

6

18. Many units, more especially those coming from quiet parts of the front, lacked training and

fighting experience. Not infrequently, the fighting efficiency of the infantry sufferel from faulty arrangements

made within the regiments for bringing up rations, ammunition, &c.

II.—Measures by which a gradual improvement was attained.

19. As the allotment of artillery ammunition, aeroplanes and anti-aircraft sections increased, and

steps were taken for machine guns to engage aviators flying low, the infantrymans lot began to improve.

His self-confidence returned and his fighting efficiency increased. Command and co-operation between all

arms were greatly assisted by the provision of large quantities of means of communication and the

re-organization of the reporting and communication systems

20. Barrage zones were made deep and narrow, and behind them the infantry lines could be lightly

held. The fact of pushing in a number of divisions led to narrower fronts and greater distribution in

depth. The allotment of fresh divisions in rapid succession made timely and regular reliefs possible, and

finally reached such a point that reserves behind the front could be trained in the light of the most recent

experience and could be employed on the construction of rearward positions.

21. The progressive completion of positions made it possible to apply the lessons of recent experience

(defence of an area with numerous trenches and switch lines, rational distribution and siting of dug outs).

22. The fact of organizing supplies within regiments before they went into line, in the light of the

experience of troops already relieved (formation of fourth platoons, organization of special carrying parties,

provision of intermediate depôts of rations, ammunition, &c.), kept the jnfantry up to fighting standard

for a longer period when in Ine and economised the employment of other units. In this way, again.

methodical counter-attacks could be made by fresh troops.

III.—Experiences and lessons.

(Based chiefly on reports from the troops.)

(a.) General.

23. Our infantry is superior to that of the enemy.— In the Somme battle, wherever the enemy gained

the upper hand, it was chiefly due to the perfected application of technical means, in particular to the

employment of guns and ammunition in quantities which had been hitherto inconceivable. It was also

due to the exemplary manner in which infantry, artillery and aeroplanes co-operated. After artillery

preparation, wherever the enemy's infantry, following up the last shell, came upon positions that were

still held, the attack usually broke down, and, if the advance was made against positions already destroyed,

the infantry could be ejected by determined and rapidly executed counterattacks

The duty of every infantry commander is, firstly, to train and educate the infantry soldier for this

hand-to-hand fighting (which should not be a privilege reserved for assault units, but should be a universal

one); next, and more difficult, to keep him physically and mentally fit to fight both before and during

an engagement; and, lastly, the most difficult of all, to get his men out of their shelters and dugouts in

tie and launch them against the enemy.

(b.) Training.

24. In this war, which is Apparently dominated by science and numbers, individual will-power is,

nevertheless, the ultimate deciding factor.

The defence of a position depends more than it ever did before on the unshakeable determination of

the subordinate commander and of each individual man to hold his position.

25. It is a sound principle to keep troops, intended for use on a certain battle front, behind this

front for about 14 days, to enable them to complete their training. In this manner, i

immediate advantage

can be taken of the lessons of the most recent fighting, while at the same time commanders can familiarize

themselves with the ground on which they are to be employed and with the special features of operations

in that locality.

26. Apart from the general regulations in force, the instructions laid down for assault formations

form the best guide for the training of the infantry soldier.

Physical fitness and confidence in his arms (rifle, hand grenade, spade, &c.) must be increased by

constant practice. Self-confidence and resolute determination are a guarantee of success, even against a

numerically superior opponent

27. The education and training of subordinate commanders is of particular importance.

To come supreme through the crises which even the best trained infantry will undergo, when suddenly

experiencing such overwhelming mental and physical sensations, especially when torn from quiet trench

warfare and hurled into a battle like that of the Somme, to combat the demoralizing effect that results from

continuously remaining in shell holes and craters, requires whole-hearted disinterestedness and self-sacrificing

care for subordinates, particularly on the part of company, platoon and subordinate commanders.

The fighting value of troops depends on the standard of training attained by the men and on the military

proficiency of the subordinate commanders.

28. The following are the most important branches of training:

(a) The education of the group❊ commander and of the individual private to the highest possible

degree of self-reliance. (In positions which often consist of unconnected shell holes, control

by platoon and company commanders is rendered extremely difficult.)

(b) The training of every single man of the infantry in the use of all patterns of German hand grenades.

(c) The training of the greatest possible number of men in the use of captured hand grenades.

(d) An increase in the personnel trained in the use of our own and of the enemy's machine guns.

Every infantry officer must be able to work a German machine gun. The gun crews must be

drilled until, when prepared for action, they can bring up an unloaded gun from the bottom of

a dug out and be ready to open fre within 30 seconds. Special practice us required in the use of

improvised mountings and sandbag supports.

(e) Patrol work.

———————

❊A group consists of 8 men under a non-commissioned officer—GS.

7

(f) Rapid counter-attack across open ground, launched on the initiative of a subordinate commander,

down to a group commander or some stout-hearted man.

(g) Methodical counter-attack, following an artillery preparation.

(h) Rapid organization of shell holes for defence (to be connected as soon as possible by an irregular

trench so as to facilitate command).

(i) The passage of areas which are under heavy shell fire (in file, lines of skirmishers, small parties).

(j) Behaviour under intense bombardment in incompleted trenches (taking cover in shell holes in

advance of the line).

(k) Practice in co-operating with artillery and with infantry aeroplanes.

(m) Training of regimental and headquarters communication sections.

Where a unit is to be employed for a special operation, it is advisable to train it in specially constructed

practice trenches, and the details of the tasks allotted to it should be thoroughly practised.

(c.) Reliefs.

29. It is often contended that, as fresh troops are coming into the line, a relief means a period of

increased strength, whereas, on the contrary, it usually means a temporary weakness. What really is of

vital importance during a relief is not the number of units in front line, but solely that the arrangement

made for responsibility and command are clearly defined and that order and close supervision are maintained.

For these reasons, reliefs must be organized carefully, thoroughly and in ample time.

30. The conduct of reliefs must be in the hands of the outgoing staff.

Before moving in, units must be provided with everything (equipment, clothing, rations, close-range

weapons, maps, signal stores, tracing tape, &c.) that they will require during the time they are employed

in the front line.

The commanders of in-coming troops will be given an opportunity of getting into touch with the infantry

pioneer, and artillery commanders of the out-going troops, and of reconnoitring the ground.

Advance parties of the relieving troops (including machine gun units) must be sent on ahead, as early

as possible, to the position to be taken over. Rear parties of the out-going troops will be retained for at

least 24 hours. The chief duty of rear parties is to ensure that no gaps occur in taking over the position and

that touch is maintained with units on the flanks. Both parties will be commanded by officers

Depressions, ravines, sunken roads, small woods or isolated farms should not be chosen as boundaries

between sectors, for, being usually exposed to heavy shell fire, they call for special precautionary measures

(construction of entanglements, distribution of troops in depth, flanking fire from machine guns)

31. Fresh troops will be led up by the most reliable guides of the out-going garrison.

These guide

must be capable of making suggestions as to the formation to be adopted at different points (file, lines of

skirmishers, or small parties). Delays, crossings and blocks occasion unnecessary losses and have a depressing

influence on the troops.

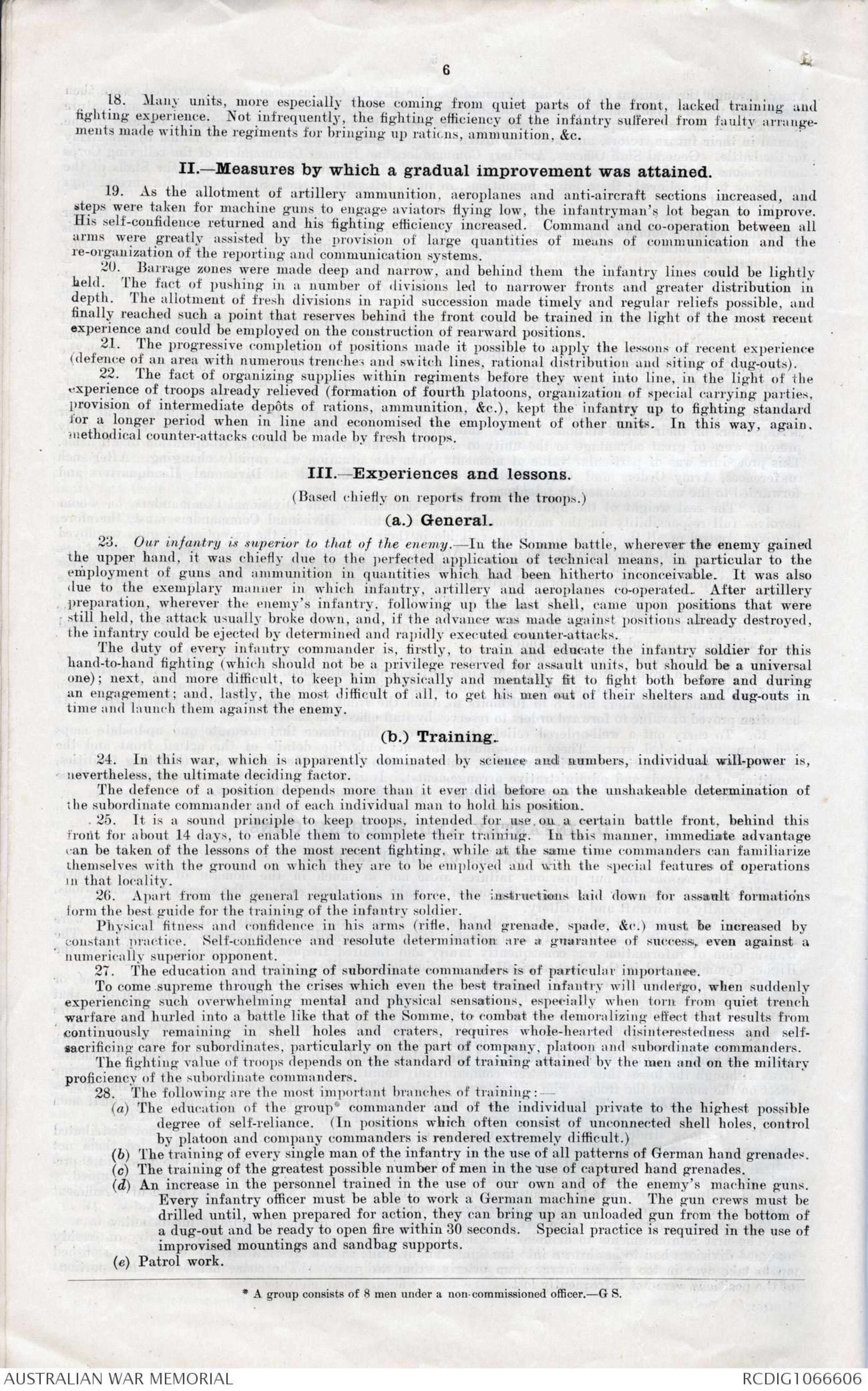

Communication trenches are best marked by signboards of the type shown below.

Diagrams - see original

32. If commanders and advance parties have already become acquainted with the ground, the trenches

and the enemy's characteristics, portions of the front line can be relieved during the first night without

cause for anxiety. This has the advantage that fresh troops come into the front line. If it has not been

possible to make sufficiently detailed arrangements for the relief, it is advisable to relieve only portions of

the supports during the first night.

Liaison and order are best guaranteed by pushing in the fresh troops chequerwise among the outgoing

troops, thus relieving, during the first night, parties on the flanks in the front line and those in the centre in

the support line.

Where positions merely consist of shell holes, the front line and the flanks of the position should be

marked out with tape.

It considerably stiffens in-coming troops in their first uncertainty, if the machine gun units are relieved

24 hours later than the infantry.

The exchange of machine guns should be avoided, but ammunition, water buckets, &c., may be handed

over

33. The nerves and endurance even of the best troops have their limits, so that timely reliefs are

absolutely essential. The utter exhaustion of troops in action usually culminates in the loss of the position.

worn out troops are incapable of strenuous efforts for months afterwards. To rush troops into action as

reinforcements at the last moment is to engage them under the most trying conditions; they will generally be

used up in a very short period, without there being any possibility of their saving the position, owing to their

ignorance of the ground.

34. Every endeavour must be made to procure a thorough rest outside the shelled area for troops that

have been relieved. Only thus can troops regain their fighting efficiency and become ft for further

employment.

(d.) Distribution.

35. The distribution of the infantry depends on battle conditions and especially on the efficacy of the

enemy's artillery. It is also affected by the ground and by the nature of the positions available

36. The fire for effect which precedes the enemy's great attacks and lasts for days, frequently rising

to an intense bombardment, soon converts the front line trenches into a succession of shell holes. This

becomes a permanent state of affairs where frequent attacks preceded by violent bombardments follow each

other in rapid succession. This hurricane of fire, which is intended to clear the way for the enemy's infantry,

sweeps right over the area occupied by the supports. The barrage zone established by the enemy behind his

objective adds to the difficulty of bringing up reserves from the rear. The infantry battle will, therefore

usually have to be decided by the troops up m the front who are completely isolated. Hence the necessity

1057

8

for distribution in depth. To avoid unnecessary losses from the intense bombardment, the front line will be

held as lightly as possible. One man for every four to six yards of front will suffice if the supports can he

accommodated close behind the front line. To compensate for this, the strength of the defence must lie in

distribution in depth.

37. The distribution of the troops must be such that, in all circumstances, the struggle for the position

can be fought out in the front line without bringing up appreciable reserves from farther in rear. Supports

posted behind the front line either in squads or in open formation, can only reach this line in time if they

are close behind it.

38. If possible, units will not be mixed, for at a critical juncture, small forces in the front line led by

commanders that the men know, are preferable to a medley of detachments, hurriedly engaged, who are

strange to each other.

It is preferable to engage units side by side, so that they can be distributed in depth in narrow sectors,

rather than engage then one behind the other. The same system of reinforcing from the rear applies equally

to bringing up supplies and replacing casualties. It has proved sound to form, for this purpose, 4th platoons

from the companies engaged and to keep them in reserve.

39. Machine guns, for the employment of which the infantry sector commander (battalion or regimental

commander) is responsible, will be spread over the zone of defence on the principle of distribution in depth.

Machine guns should be sparingly employed in the front line trench, where they will generally be

prematurely put out of action by the intense bombardment. They will seldom have a good frontal field of

fire in positions which are sited on reverse slopes; Hanking effect should consequently be employed. Their

effect is to be supplemented by that of machine guns sited in pairs farther in rear, as far as possible in

commanding positions, in such a manner that zones of fire can be formed both in front of and within the

defended area.

40. The experience of the Somme battle teaches that an infantry regiment which has one battalion in

front line, one in support, and one in reserve, can hold a front of about 800 metres for some 14 days in a

defensive battle. After this period, relief is generally necessary.

(e.) Construction of positions.

41. The measures required in the construction of positions have, as their basis, the necessity of having

infantry organized in depth and of maintaining the garrison of the position ready for action.

42. In laying out new, and in improving existing positions, the infantry line must be traced to accord

with the situation of the artillery observation posts. The principal artillery observation posts must not

be exposed to fire directed on the infantry line. The dust and smoke, and the moral effect on the observer if

posted in the infantry line, render observation in it difficult, if not impossible. An observer is useless if

means of communication are broken.

43. The front infantry trenches are well placed if they are situated on a reverse slope out of sight

of the ground observation of the enemy's artillery and are overlooked directly by their own artillery observers

from a position at least 550 yards in rear. At the same time these observers should be able to see well

into the ground over which the enemy must attack for at least 200 yards in front of their own wire, and

it should be possible to overlook, either from the front or a flank, at least a part of the ground behind

this belt over which the enemy must make his approach marches. A very short field of fire is sufficient

for the infantry. A line of this nature in undulating country will be generally a reverse slope position.

If the enemy breaks into such a reverse slope position, his infantry will have to fight exposed to our

concentric, well observed and most effective fire, without the support of artillery which is assisted by ground

observation.

44. For an obstinate defence of the front position, it is not sufficient to dig a few parallel lines of

trenches one behind another; a broad defensive zone must be constructed composed of a network of trenches

disposed in depth, with plenty of switches and cross trenches. Every fire trench, communication trench,

and approach trench must, no matter in what direction it leads, be prepared for defence at least on one

side, and be provided with an obstacle and dug-outs for its garrison or assault detachment. An enemy

who penetrates the front line of trenches must find himself opposed not only in front but in flank at the

next line, and it must be possible to counterattack him from all sides. If he cannot be turned out at

once, he will at least be bottled up in a pocket, and thus the best condition for a deliberately planned

counterattack will be created

45. Even a position formed of broad, deep; defensive zones is not enough to stop the attempts of a

strong enemy to break through, if he has made careful preparations. The power of concentrated artillery

fire is so great that losses of ground will be inevitable even in the finest positions. Behind the front

position, therefore, there must be at least two rearward positions, spaced so far apart from one another

that the enemy will be compelled to change the position of his artillery in order to attack them It must

be a fixed principle in battle that as many new positions are organized behind as positions are lost in

front.

46. It is desirable in constructing new positions that have to be organized during a battle to begin by

making an entanglement in advance of the front fghting line, and simultaneously to commence the dug-outs

of the second line. From this framework, a position of two lines will gradually be developed. The trenches

themselves come last.

47. In addition to the continuous rearward positions, all localities for about 9 miles behind the front

line of trenches must be organized for defence. In connection with this, all available shell-proof cellars

must be converted into dug-outs and provided with the necessary number of entrances. As far as possible.

machine gun emplacements should be provided to sweep the ground between the localities

48. In the front trenches of a position, only sufficient shell-proof dug outs are required as will shelter

the garrison, which should be kept as weak in numbers as can be. In the rearward trenches it is hardly

possible to make too many dug-outs for the mass of the infantry. The following conditions have proved

most suitable:– 24 to 33 feet of earth or 5 feet of concrete overhead cover; at least two entrances a good

distance apart; chambers for 10 to 20 men.

The deeper the dug outs the more important are a good wide entanglement, continuous observation of

the foreground and reliable alarms. Dug outs without these precautions are mere man traps.

The construction of dug-outs is absolutely indispensable along Hines of approach for the temporary

shelter of reliefs and carrying parties if caught by shell fire, in the communication trenches, for runners.

and along the route of cable trenches for the linemen.

9

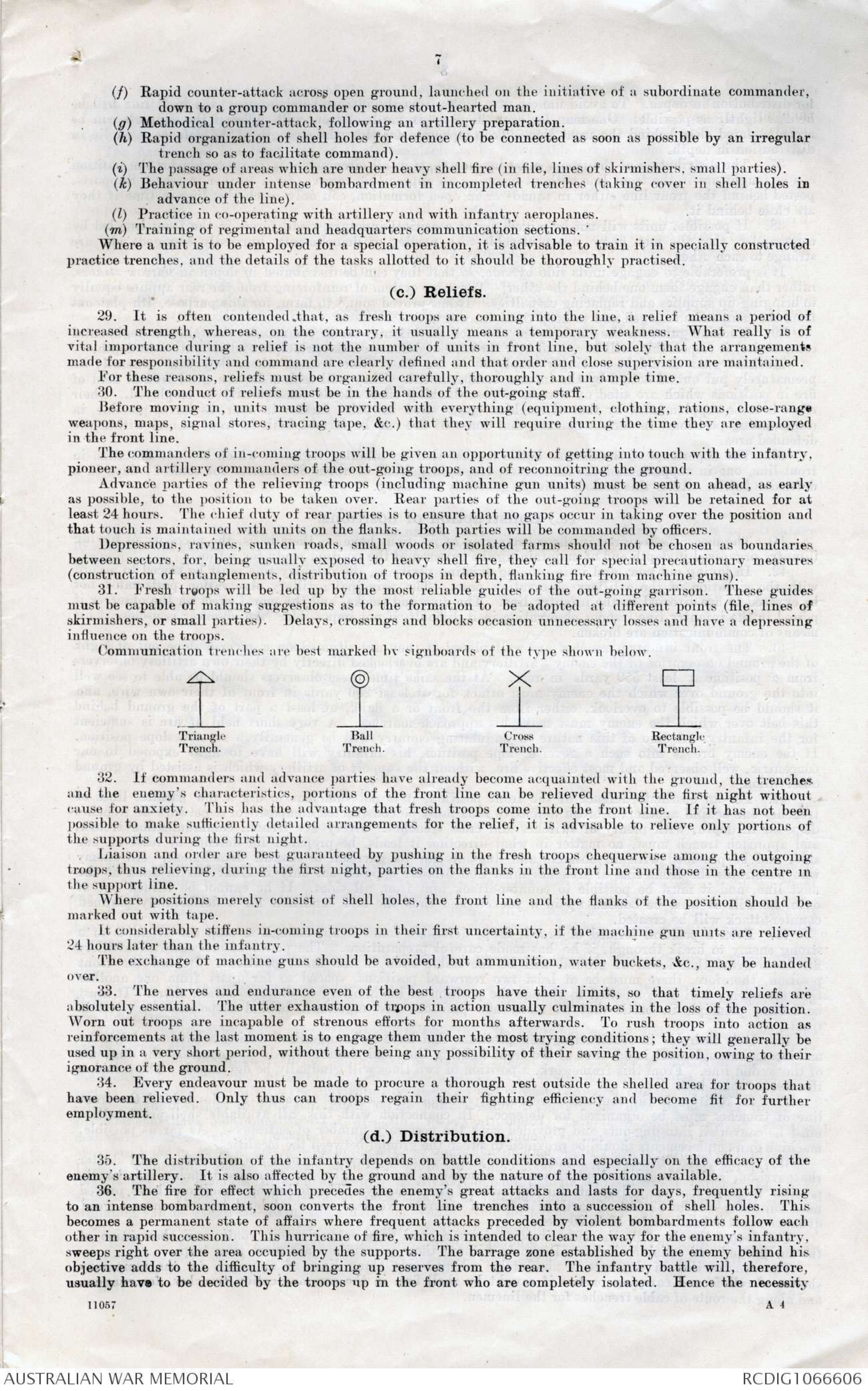

49. Entanglements in advance of the front trenches must be as strong as possible, must be erected in

regular lines and must cover wide spaces of ground for 60 to 200 yards in depth. This will force the enemy

to an enormous expenditure of ammunition to destroy them, and will ensure that, even after several days

wire cutting, he will still find a tangle of wood, wire and iron in front of him.

The flanking of the front line of the entanglements by a suitable arrangement of machine gun fire

should not be overlooked.

Diagram - see original

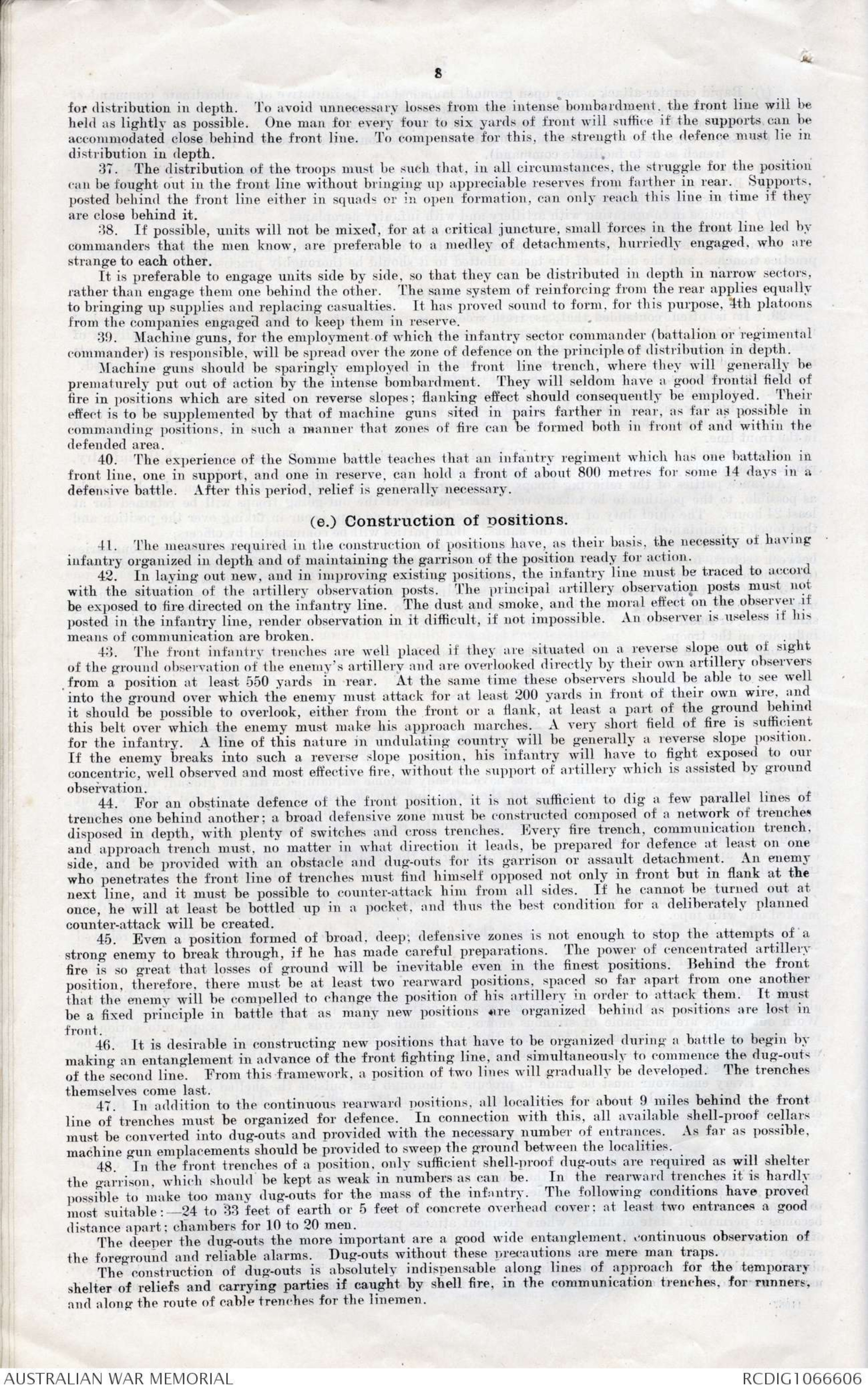

To leave a free field for the counter-attacks of the garrison of the rearward trenches, it is an advantage

to arrange the entanglements of the rearward lines chequerwise. There must be plenty of material ready

to block the gaps (knife rests and concertinas).

Diagram - see original

50. The construction of infantry observation posts, command posts and latrines is of special importance,

as are also bomb-proof❊ shelters for ammunition, weapons for close combat (grenades, &c.), supplies, water

tanks and kitchens in the rearward trenches and support positions.

Built up machine gun emplacements are soon smashed to pieces unless they are shell-proof (against

heavy artillery). As a rule, the best course is to provide shell-proof❋ shelters for the machine guns in which

they are to be kept until required for action, when they are fired over the parapet.

Covered battle emplacements of concrete or armour plates are usually only possible on steep reverse

slopes. They must not be conspicuously high.

In view of the importance of signal communications, special dug-outs are necessary for them; these

should be suited to their various natures (telephone offices, visual signalling, trench wireless, power buzzer

and listening sets)

Open cable trenches have proved more serviceable than buried cable, as the difniculty of repairing the

latter us very great.

51. A well considered scheme and plenty of dugout dressing stations are required for the care of

the wounded. For periods of special activity there must be at least one medical dug out in each company

sector. It should be built in the immediate vicinity of the second (support) trench, be large enough to

accommodate 14 men lying down and must be bomb-proof.' There must also be sufficient space for

the Medical Corps personnel, first-aid dressings, trench stretchers, blankets, mineral water, disinfecting

material, reserve anti-gas material, supplies, &c. There should be larger medical dug- outs capable

of holding 25 to 40 men and a larger quantity of medical stores in the vicinity of the battalion reserve.

In each regimental sector, dug-outs should be arranged about 2,000 to 3,000 yards behind the front line

(cellars are most suitable, in each of which about 100 wounded can be accommodated lying down). The

entrances, of which there should be at least two, of all medical dug-outs must be constructed so that

stretchers can be easily carried in and out.

❋In the 2nd Edition of "Stellungsbau " dated 15/12/16 bombensicher (bomb-proof, is defined as poof against continuous

bombardment by 8-inch howitzers and heavy trench mortars, and against single, hits by heavier natures; schus ssicher (shell-proof) as

proof against continuous bombardment by 6-inch howitzers–G.SI.

11057 A5

10

52. Defensive positions formed by connecting shell holes, which are the rule in the front line during

heavy fighting, have the advantage that they are difficult to recognise and are correspondingly less effectively

shelled. Infantry, therefore, feels safe in them and is disinclined to dig the more easily seen continuous

trenches. The advantages of shell hole positions are, however, practically negligible in comparison with

the following disadvantages:–

Lack of accurate definition of the firing line; continual changes in the position of the line; uncertainty

when arranging barrage fire; increased difficulty, if not absolute impossibility, of control of the men; nearly

complete absence of any kind of leading, which makes itself particularly noticeable as the men are so

dispersed, and nearly always involves loss of ground and casualties in missing; more rapid expenditure

of the physical power of the men, for they cannot shelter themselves from weather in the shell holes, and in

heavy rain are often up to the waist in mud, whereas in continuous trenches some sort of drainage can be

arranged quickly. In shell hole positions, in which obstacles are generally lacking, the scattered groups

are exposed to any surprise by hostile patrols, and a counterattack lacks supporting points and jumping-off

trenches.

Rules can hardly be laid down for the construction of shell hole positions during the fight. The obvious

procedure here is at once to establish nests of infantry consisting of one or two groups, supported, if

circumstances render it advisable, by one or two machine guns, in or behind the line of shell holes

occupied, and to construct obstacles and dug outs for them. By degrees, these nests are linked up with one

another and with the switch trenches and retired positions behind them.

(f.) Defence.

53. An active conduct of the defence is absolutely essential even against an enemy who is far superior

in numbers. Intense activity of patrols, and raids on weak points of the enemy's position interfere with his

preparations for attack and compel him to keep in a condition of continual readiness for our attacks, and so

to hold his positions more strongly even at times when he is not contemplating an attack himself.

54. In shell hole positions, in which the infantry finds but little shelter from the enemy's fire, an active

defence is of greater importance. Every man must understand that the losses caused by the enemy's artillery

fire diminish, the closer our front lines are to those of the enemy.

The completion of the position should

therefore, be combined with a pushing forward of our lines, where the situation permits

55. It is the task of the artillery and of the Minenwerfer to nip the enemy's attack in the bud as far as

possible. If the enemy none the less succeeds in leaving his trenches for the assault, it should be possible to

repulse every attack by holding the front line with a weak garrison, provided with some machine guns and

a large supply of close range weapons, in combination with well directed and rapidly opened barrage fire, and

also with machine guns sited on points of rising ground farther in rear.

56. It is absolutely essential to remember that, in spite of "defended areas," the fighting must take

place in the foremost line and, if this is overrun, for its recapture

57. The necessary preliminary for the repulse of a hostile attack is that our own infantry, distributed

in depth, shall be kept fit for fighting in spite of effective and intense bombardment for days by the enemy's

artillery. Continual work on the positions, and a good organization of the supply of rations and ammunition,

are the most important points in maintaining their fighting strength.

58. As a matter of principle, every unit must fight in that portion of the foremost position which is

given to it to defend.

The voluntary evacuation of a position, or of portions of a position, can lead to most disastrous results

for the troops on the flanks. The voluntary evacuation of positions must, therefore, only take place with the

express permission of the Higher Commanders, who are in a position to realize its effects on the troops on the

flanks and on other arms (artillery).

59. Such an evacuation can scarcely ever be carried out methodically except by night or in very misty

weather, for experience shows that during the fighting every visible movement by day is immediately

subjected to the most intense fire, and all movements cause heavy losses owing to the fact that communication

trenches are usually entirely lacking.

60. No objection can be taken to the temporary evacuation in a forward direction of portions of the

foremost line which are exposed to very heavy shell fire, in the case of good troops who are well trained in

initiative and in rapid counter-attack. The movement will then consist in individual groups dashing forward

into shell holes which lie in front of their position.

61. A movement to the flank under hostile fire can only be carried out on a very narrow front, and then

by moving quickly from crater to crater, or by creeping along the remains of the trenches. During the

battle, the front covered by the enemy's intense bombardment will usually be so broad that nothing is gained

by moving the trench garrison to the flank. The manouvre, however, is always exposed to the great risk that

the enemy observes the evacuation, lifts his fire further forward, and immediately occupies the position which

has been evacuated.

62. The risk is very much increased if the garrison of a trench retires from its foremost line. All intense

artillery fire, even if directed against a narrow front, covers the ground in rear. As a general rule, all line

which lie behind the foremost trenches are methodically shelled. If our trench garrison moves to the rear

in the zone of fire it quickly becomes demoralized. All experience proves that such troops can no longer be

expected to carry out a counter-attack. The result is, almost invariably, the loss of the portion of the

position which has been evacuated and, as a further result, the creation of a very difficult position for the

troops on the flanks. These, if the enemy attacks on a broader front, are usually attacked frontally and on

the flank, and have to fight under the most unfavourable conditions.

63. During the battle of the Somme, the methodical evacuation of portions of the position depended on

obtaining permission from Army Headquarters, and every evacuation of positions, even to the smallest extent,

carried out on the responsibility of the individual commander was forbidden. Every man was obliged to fight

at that point at which he was stationed; the enemy's line of advance could only lead over his dead body.

Army Headquarters believes that it was owing to this firm determination to fight, with which every leader

was inspired, that the enemy, in spite of his superior numbers, bled to death in front of the serried ranks of

our soldiers.

64. If the enemy succeeds in overrunning the front lines in an attack, he can only be ejected by

immediate counter-attacks which must envelope him on all sides. If he has once managed to consolidate his

hold on our positions, a methodical counterattack, which takes time, is necessary.

65. Penetration of our lines by the enemy occurs during the battle not only in the case of attacks which

are carefully prepared, but is frequently effected by patrols or small detachments with machine guns which

11

penetrate or sap their way into gaps, particularly in shell hole positions. These small detachments are

gradually followed by larger forces. This kind of nest is often scarcely noticed to begin with, or does not

have sufficient attention paid to it. The seriousness of the situation is usually frst recognised when it is too

late. Instead of cutting of the nest or countering it by a vigorous attack, a methodical attack has to be

made.

The necessary preparations for methodical attacks on nests of this kind must be made at once, as soon asthe

nest is discovered. The most important are: — To reconnoitre the position as quickly as possible, to block the

nest off on all sides, so that a shell hole is occupied at once as close as possible behind the breach. A trench

should then be dug leading to the shell hole. Other trenches should be dug in which assault detachments can

be assembled; patrols should feel their way towards the danks of the enemy who has penetrated our position

and should dig themselves in. Every available means to assist in the attack should be carefully concentrated,

such as assault-detachments, Flammenwerfer, Granatenwerfer, light Minenwerfer, infantry gun batteries, &c.

(g.) Immediate and methodical counter-attacks.

66. An immediate counter-attack can scarcely ever be ordered by the Higher Commanders. It must be

the result of the quick initiative of the commanders, subordinate commanders and men in the front line

Every man must be trained to eject, on his own initiative, an enemy who has penetrated our positions, and

not to rest content until the foremost line has been entirely cleared. Quick, mobile bombing parties, moving

rapidly over the open or along the trenches, vie with assault detachments specially distributed and allotted

to special objectives. The commanders of the supports must take in the situation and make up their minds

quickly and attack the enemy, distributing their groups, platoons and companies to meet the situation,

allotting special tasks to detachments, and giving them short and precise instructions as to objectives. For

this purpose, it is necessary that the quarters of supports and reserves, when the nghting develops its full

intensity, should be distributed over different points in the ground (in trenches and dug-outs, or on the slopes

of hills). The collection of numbers of dug outs or camps at one point, will not escape the enemy's notice.

by opening heavy fire on such points, he puts the massed supports accommodated there out of action at the

critical moment.

It is very important that, in addition to the transmission of information from front to rear, communication

should also be established from rear to front. Troops which wait for reports to reach them from the

front will always come up too late for a counter-attack. Continual observation of our own and the enemy's

positions is absolutely essential on the part of the sentries of the supports and reserves. Commanders must

keep themselves continually informed as to the situation, and at critical moments keep a look out themselves,

foronly thus can they have a clear idea of what is happening and come to quick and correct decisions.

67. The execution of methodical counterattacks cannot be dispensed with even in a purely defensive

battle. They are necessary in order to recapture important points which have been lost, or at least not

to leave the enemy full freedom of action. If they are well prepared, they do not involve more casualties

or a greater expenditure of ammunition than do passive endurance of an intense bombardment and numerous

unnecessary requests for barrage fire, which become more frequent as the self-confidence of the troops

diminishes as a result of adopting a purely passive attitude.

In every attack, rearward positions, strong points, and flanking positions must be held by emergency

garrisons as a precaution against possible defeats.

68. Methodical attacks may either be carried out as surprise attacks without artillery preparation or

with the emplovment of intense artillery preparation. A compromise between the two methods nearly

always leads to failure.

69. Surprise attacks should be limited to a narrow front and can only be carried out if the habits

of the enemy are exactly known, if the approach to the enemy's position is short and free of obstacles

and if it is possible to penetrate into the enemy's position at several points simultaneously and with practically

no casualties. Thorough rehearsals, a detailed allotment of tasks down to individuals, taking full

advantage of the weather (e.g., mist or twilight), and simultaneous and rapid action are preliminary conditions

necessary for the success of a surprise attack.

70. Raids on a larger scale will, as a rule, only be successful after intense artillery preparation. The

preparatory measures to be carried out by the artillery (accurate registration on all the targets which are

to be shelled in the course of the raid) and the expenditure of ammunition must be so regulated that

the portions of positions to be captured are really shelled into a condition in which they are ready to be

assaulted. It will often be necessary to evacuate our own front lines during the fire for effect; this can

be done without hesitation if our artillery fire is properly directed against the enemy's trenches.

71. Troops who have been lying widely scattered in trenches which have been destroyed and in shell

holes, with insuffcient food, and who are longing for the day when they will be relieved, will only be

induced to attack cheerfully and resolutely at a fxed time, without the possibility of being thoroughly

instructed as to the reasons and objective of the attack, if their leaders are extraordinarily effcient, and then

only, asa rule, in driblets. A necessary preliminary for a successful attack on a large scale is fresh infantry

to make the assault (a regiment to every 1,000 yards of front) and the detailing of a relief for the assault

troops. The original troops in the line may be employed for this purpose if they have not been exhausted

by previous nghting.

72. It is advisable not to relieve the troops who have made a successful assault immediately, but two

or three days later. Troops who have won ground after heavy fighting will hold the captured position

more tenaciously than new troops who also, in many cases, do not know the ground sufficiently well.

To avoid any weakening during these two days of the troops who have made the assault, special parties.

commanded by offcers, must be detailed to evacuate prisoners and wounded, to clear the ground and, above

all, to bring up supplies of building material. Thorough and special infantry preparations for this work

are necessary, even with well trained troops.

Machine guns form a support and protection for the assaulting troops in immediate and methodical

counter-attacks, and hold the enemy to his trenches by flanking fire, especially at the moment when the

assaulting troops leave their trenches. The section commanders of the machine guns specially detailed

beforehand to follow up the assault, advance with the assaulting infantry, so as to reconnoitre the captured

position at once for suitable gun positions.

Machine guns should be brought up to the captured position as soon as the infantry has taken it.

They must be dug in before a hostile counter-attack is delivered or the enemys annihilating fire is opened

against the captured position. To bring up machine guns from the lines in rear into the position from

11057 A 6

Sam scott

Sam scottThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.