Charles E W Bean, Diaries, AWM38 3DRL 606/244/1 - 1916 - 1933 - Part 4

8. 29

And I believe the Authorities say that we are outdoing Verdun.

So you can see I had no very gentle baptism.

I was buried twice, just sort of half buried, and able to

wriggle out myself, much dazed and very frightened. Then I fell

down or was knocked down a dozen times. But I suffered nothing

but minor scratches.

We had practically no hand-to-hand fighting. The Germans

always ran. My nearest approach to that anything like that was

leading out a bombing party just before dawn to bomb out a German

[*?1/8/16*] stronghold just in front on our line at "A". We had to bear

continuous fire, mostly shells, but also machine guns, trench mortars,

bombs, and rifle bullets. We had no dug outs there at all, and

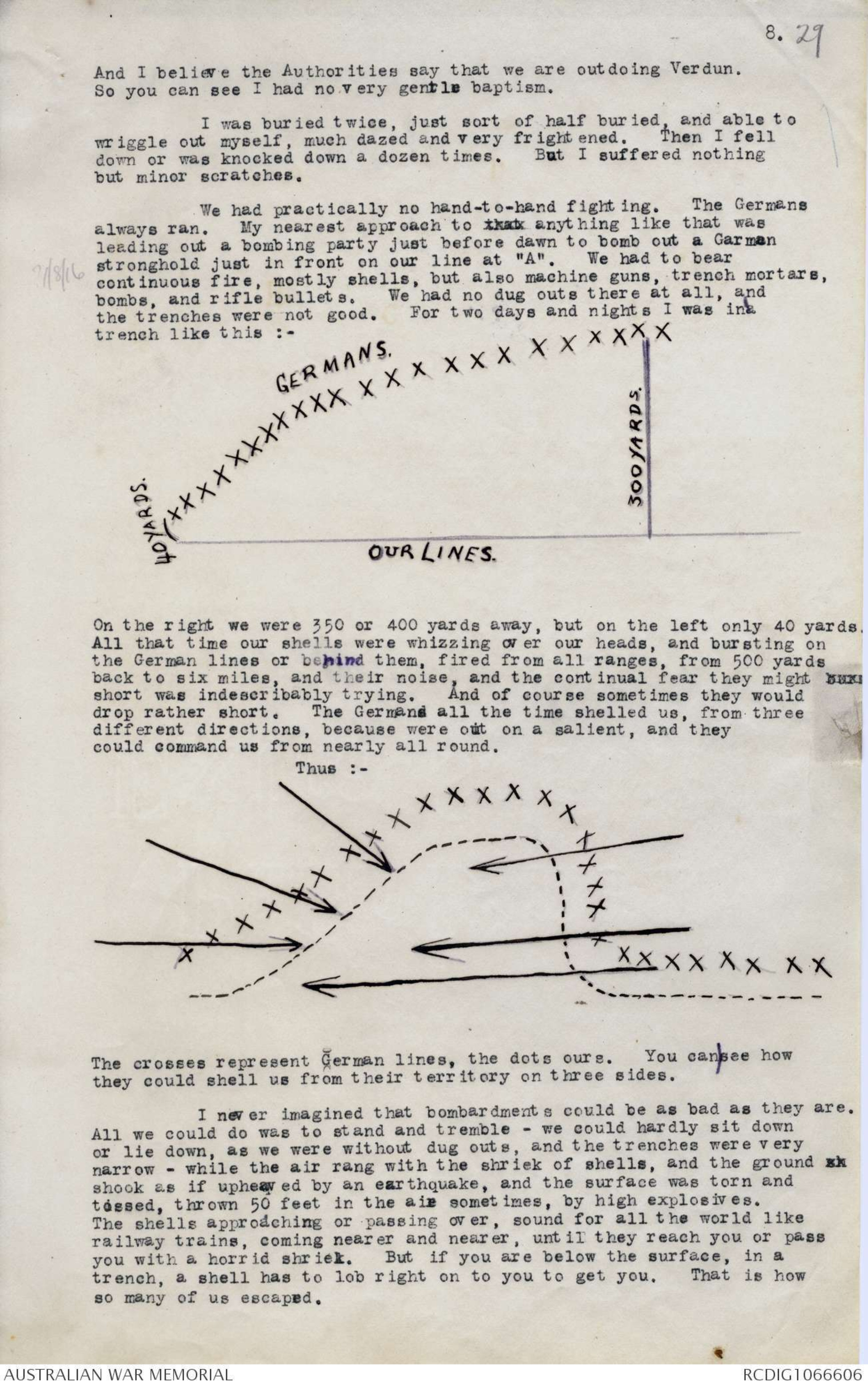

the trenches were not good. For two days and nights I was in a

trench like this :-

Diagram - see original document

On the right we were 350 or 400 yards away, but on the left only 40 yards.

All that time our shells were whizzing over our heads, and bursting on

the German lines or behind them, fired from all ranges, from 500 yards

back to six miles, and their noise, and the continual fear they might xxxx

short was indescribably trying. And of course sometimes they would

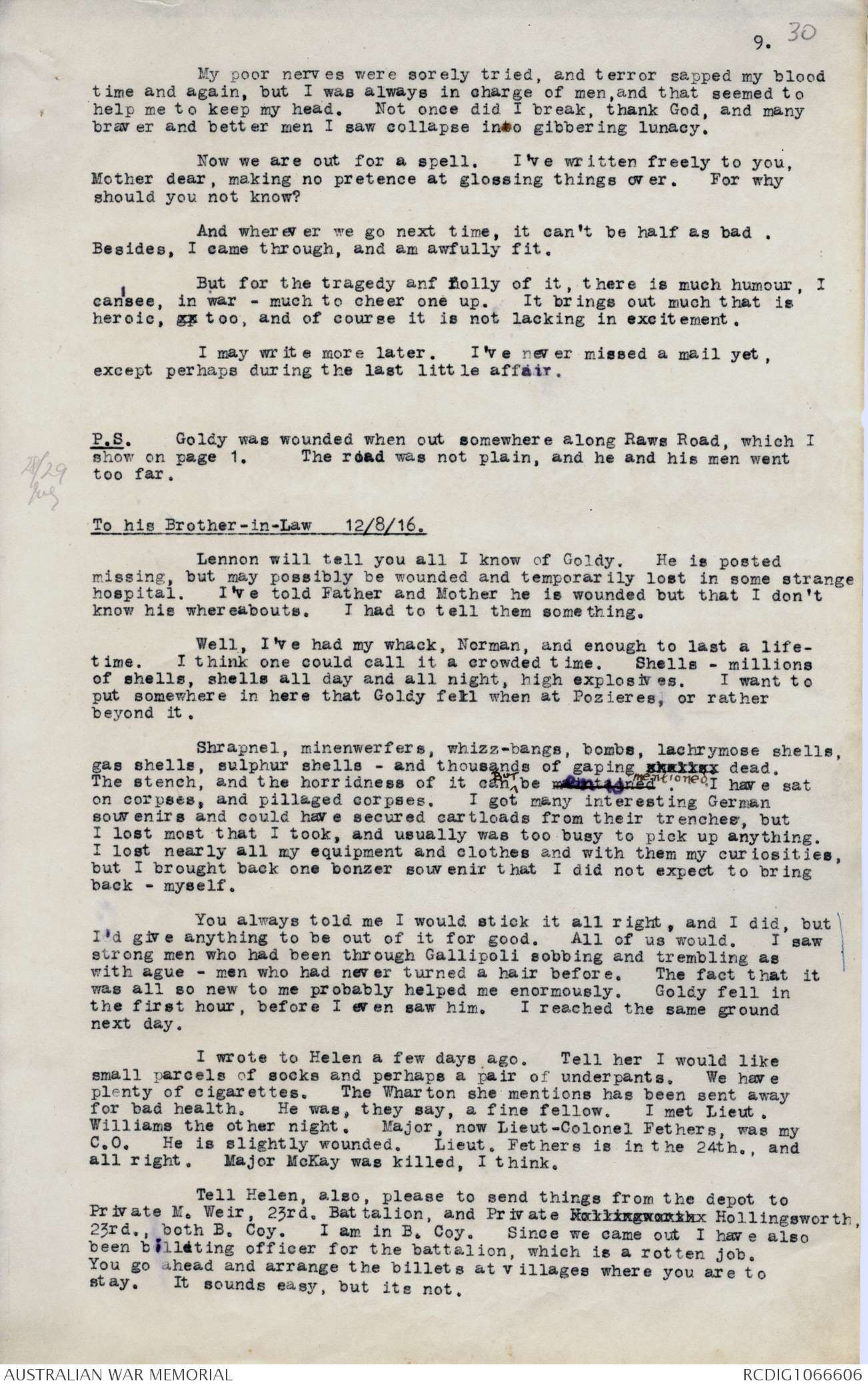

drop rather short. The Germans all the time shelled us, from three

different directions, because were out on a salient, and they

could command us from nearly all round.

Thus :-

Diagram - see original document

The crosses represent German lines, the dots ours. You can see how

they could shell us from their territory on three sides.

I never imagined that bombardments could be as bad as they are.

All we could do was to stand and tremble - we could hardly sit down

or lie down, as we were without dug outs, and the trenches were very

narrow - while the air rang with the shriek of shells, and the ground xx

shook as if upheaved by an earthquake, and the surface was torn and

tossed, thrown 50 feet in the air sometimes, by high explosives.

The shells approaching or passing over, sound for all the world like

railway trains, coming nearer and nearer, until they reach you or pass

you with a horrid shriek. But if you are below the surface, in a

trench, a shell has to lob right on to you to get you. That is how

so many of us escaped.

9. 30

My poor nerves were sorely tried, and terror sapped my blood

time and again, but I was always in charge of men, and that seemed to

help me to keep my head. Not once did I break, thank God, and many

braver and better men I saw collapse into gibbering lunacy.

Now we are out for a spell. I've written freely to you,

Mother dear, making no pretence at glossing things over. For why

should you not know?

And wherever we go next time, it can't be half as bad.

Besides, I came through, and am awfully fit.

But for the tragedy anf folly of it, there is much humour, I

can see, in war - much to cheer one up. It brings out much that is

heroic, gx too, and of course it is not lacking in excitement.

I may write more later. I've never missed a mail yet,

except perhaps during the last little affair.

P.S. Goldy was wounded when out somewhere along Raws Road, which I

show on page 1. The road was not plain, and he and his men went

too far.

[*28/29

Aug*]

To his Brother-in-Law 12/8/16.

Lennon will tell you all I know of Goldy. He is posted

missing, but may possibly be wounded and temporarily lost in some strange

hospital. I've told Father and Mother he is wounded but that I don't

know his whereabouts. I had to tell them something.

Well, I've had my whack, Norman, and enough to last a lifetime.

I think one could call it a crowded time. Shells - millions

of shells, shells all day and all night, high explosives. I want to

put somewhere in here that Goldy fell when at Pozieres; or rather

beyond it.

Shrapnel, minenwerfers, whizz-bangs, bombs, lachrymose shells,

gas shells, sulphur shells - and thousands of gaping shelle, dead.

The stench, and the horridness of it can ∧but be mentioned, mentioned. I have sat

on corpses, and pillaged corpses. I got many interesting German

souvenirs and could have secured cartloads from their trenches, but

I lost most that I took, and usually was too busy to pick up anything.

I lost nearly all my equipment and clothes and with them my curiosities,

but I brought back one bonzer souvenir that I did not expect to bring

back - myself.

You always told me I would stick it all right, and I did, but

I'd give anything to be out of it for good. All of us would. I saw

strong men who had been through Gallipoli sobbing and trembling as

with ague - men who had never turned a hair before. The fact that it

was all so new to me probably helped me enormously. Goldy fell in

the first hour, before I even saw him. I reached the same ground

next day.

I wrote to Helen a few days ago. Tell her I would like

small parcels of socks and perhaps a pair of underpants. We have

plenty of cigarettes. The Wharton she mentions has been sent away

for bad health. He was, they say, a fine fellow. I met Lieut.

Williams the other night. Major, now Lieut-Colonel Fethers, was my

C.O. He is slightly wounded. Lieut. Fethers is in the 24th., and

all right. Major McKay was killed, I think.

Tell Helen, also, please to send things from the depot to

Private M. Weir, 23rd. Battalion, and Private Hollingworthx Hollingsworth,

23rd., both B. Coy. I am in B. Coy. Since we came out I have also

been billeting officer for the battalion, which is a rotten job.

You go ahead and arrange the billets at villages where you are to

stay. It sounds easy, but its not.

10. 31

Love to Helen and dear old Betty, God bless her. I often think

of her.

Yours, ALEC.

To Sir Lauchlan Mackinnon, 12th. Aug. 1916.

I want to let you know that Short and Robinson and I are all

right, though plentifully shaken, after 11 dreadful days and nights in

the Great Push. We were in fighting that, they say, outdid Verdun,

and our losses were unspeakably heavy. You will probably know all that

by now. Robinson was there, but I understand he was called away to go

to some school of instruction on machine-gunnery before he got into the

thick of it. He is all right now, anyhow. Short was wonderful - a

perfect hero - quiet, serene philosophicxxx philosophic, though shelled

from trench to trench and crater to crater, torn and tattered, unshaven,

sleepless and unfed. I saw him, calm and collected, when giants of

physical strength were cowed and helpless, and iron veterans of Gallipoli

were gibbering xxxxxxx lunatics. Never once did he lose his head, never

once did I see his courage falter. And his very calmness did countless

good in steadying the xmen xx around him. And it was all the will in

him, the determination to stick it, that made him what he was - not nature -

nor physical courage, nor natural strength, but just the fine spirit in

that frail body. Short will get no decoration. They do not go to men

like that. No senior officer was there to see it, and Short never

boasts his prowess from the housetops. Men have already got medals and

ribbons for doing in that fight one-tenth of what Short did. I just

want you and our old friends in "The Argus" to know, though, because we will

both be in it again very soon.

I saw a lot of Short. We were in the same Battalion, and were

thrown together repeatedly. I laugh now to think how I met him two or three

times out in front of the German trenches, and how invariably, it was dark -

he would say with his old-fashioned drawl "Hello, Raws, is that you?"

Sometimes we'd have a little consultation, sometimes a whispered joke.

Usually We’d ask hurried questions, as to what we were doing, and how our

jobs had crossed one another in "No Man’s Land". The first time we were

digging in in front of the Germans, under heavy fire, and made quite visible

by the German flare rockets. All our senior officers (the only two there)

had been hit or lost, so we hurriedly decided to tackle the whole job

ourselves, and we just got it through by daylight. Short gave his coat

to a wounded man, that night, I remember,

The glories of the Great Push are great, Sir, but the horrors are

greater. With all I'd read, with all I’d heard by word of mouth, with

all I had imagined in my mind, I yet never conceived that war could be so

dreadful. The carnage in our little sector was as bad, or worse, than

that of Verdun, and yet I never saw a body buried in ten days. And when

I came on the scene, the whole place, trenches and all, were spread with

dead. We had neither time nor space for burials. And the wounded

could not be got away. They stayed with us and died, pitifully, with us,

and then they rotted. The stench of that battlefield spread for miles

around. And the sight . . . . the limbs, the mangled bodies, and stray

heads.

We lived with all this for eleven days, eat and drank and

fought amid it, but no, we did not sleep. Sometimes, we just fell

down and became unconscious. You could not call it sleep.

And the men who say they believe in war, Sir, should be hung.

And the men who won't come out and help us, now were in it, are not fit

for words. Had we more reinforcements up there many brave men now

dead, men who stuck it, and stuck it, and stuck it till they died, would

be alive today. Do you know, Sir, that I saw with my own eyes, a score

of men go raving mad! I met three in "No Man’s Land" one night.

Of course, we had a bad patch. But it is sad to think that one has to

go back to it and back to it, and back to it, until one is hit.

I find that among the xx men and officers there is great

bitterness against those who are staying at home and taking their jobs

and their businesses, and the promotions that would have been theirs

had they, too, stayed at home.

11. 32

We who are here see no end in sight. The Germans are still

fighting well, and though we can beat them hand to hand, I don't see

how we can break down their artillery.

Please remember me to Dr. Cunningham, Mr. Fricker, Mr. Maling,

Hurst, Brennan, Allan, Mackintosh, and my other good friends in

"The Argus". And pay my respects to Lady Mackinnon.

To his Sister. August. 16th.

I am still in billets, but we shall be in the fight again

any moment.

I enclose a few souvenirs from the Somme. The tooth pick

plain piece of metal is a prong from a German fork, taken from a

dead German's haversack. The card was taken from another. Many of

these were removed in my presence, but I kept very few, and

subsequently lost all my equipment and most of the things out of my

pockets, helping a wounded man through a very heavy barrage of fire

on about August 3rd. I meant to send you a piece of curtain removed

by my own hands from a German dug out, but have lost it. You will see

the little cannon has a French inscription.

The paper knife I think I had in my pocket. I forget what

the little bolt, xxx things are - odd things off German equipment ∧or taken

from German pockets. The medal is from a German, killed by a Stokes

mortar fired under my direction into a German stronghold I found at

daybreak August 1st., when in charge of a corner of our line.

Goldy's charge went right past this stronghold, which afterwardx

howev er, was takenx not taken for some days afterwards.

Quite frankly, of Goldy I know no more as yet. He is said

to be in hospital, but in the confusion of war up here one cannot tell

If he is posted as missing by the time you get this it will mean that

he has not been traced to any hospital.

I write of him as still alive, but it must be admitted that

hope ebbs.

Much love to my dear Father and Mother, telling them to be

of good hope.

Life seems to us to be of so little importance out here.

Our next fight will be short and sharp, I think. We have

not the numbers to do more. So if you have heard nothing of me when

you get this, you will know that I will be all right for a good while.

For after this we must have a spell to reorganise and get

reinforcements.

To his Father. 19th. August, 1916.

Your letters of the end of June - 27th. or so - to hand, and

much appreciated - very much indeed.

There is no further news of Goldy, though as I am moving in to

the line again for another attack, news would quite possibly not reach me.

So far as I can ascertain he has not been found at any hospital,

though previously unofficially reported to have gone through one of them,

called a clearing station. If he has not been found by the time you

receive this, he will have been posted as missing. In fact he is already

posted as such.

I write of him coldly and without emotion, because, Father, it

is impossible that one give way to the expression of grief just now.

And I do trust that you and Mother, should good news not have reached you

will be able to sustain yourselves.

Should you find it difficult to write to me for a time, I shall

understand.I would advise you to place no great hope in Goldy’s

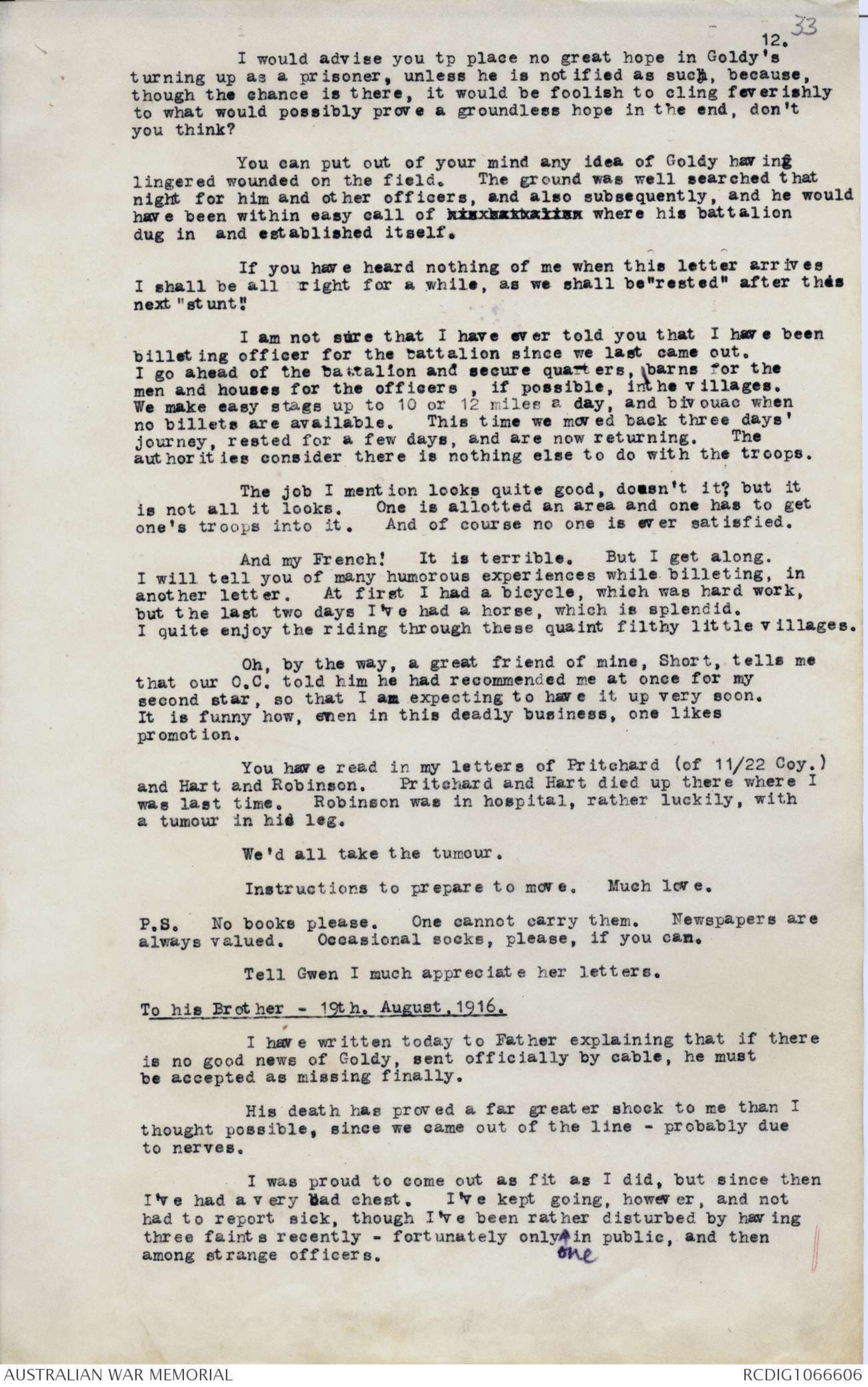

12. 33

I would advise you tp place no great hope in Goldy’s

turning up as a prisoner, unless he is notified as such, because,

though the chance is there, it would be foolish to cling feverishly

to what would possibly prove a groundless hope in the end, don't

you think?

You can put out of your mind any idea of Goldy having

lingered wounded on the field. The ground was well searched that

night for him and other officers, and also subsequently, and he would

have been within easy call of his battalion where his battalion

dug in and established itself.

If you have heard nothing of me when this letter arrives

I shall be all right for a while, as we shall be "rested" after this

next "stunt."

I am not sure that I have ever told you that I have been

billeting officer for the battalion since we last came out.

I go ahead of the battalion and secure quarters, barns for the

men and houses for the officers, if possible, in the villages.

We make easy stags up to 10 or 12 miles a day, and bivouac when

no billets are available. This time we mov ed back three days'

journey, rested for a few days, and are now returning. The

authorities consider there is nothing else to do with the troops.

The job I mention looks quite good, doesn't it? but it

is not all it looks. One is allotted an area and one has to get

one's troops into it. And of course no one is ever satisfied.

And my French! It is terrible. But I get along.

I will tell you of many humorous experiences while billeting, in

another letter. At first I had a bicycle, which was hard work,

but the last two days I've had a horse, which is splendid.

I quite enjoy the riding through these quaint filthy little villages

Oh, by the way, a great friend of mine, Short, tells me

that our O.C. told him he had recommended me at once for my

second star, so that I am expecting to have it up very soon.

It is funny how, even in this deadly business, one likes

promotion.

You have read in my letters of Pritchard (of 11/22 Coy.)

and Hart and Robinson. Pritchard and Hart died up there where I

was last time. Robinson was in hospital, rather luckily, with

a tumour in his leg.

We’d all take the tumour.

Instructions to prepare to more. Much love.

P.S. No books please. One cannot carry them. Newspapers are

always valued. Occasional socks, please, if you can.

Tell Gwen I much appreciate her letters.

To his Brother - 19th. August, 1916.

I have written today to Father explaining that if there

is no good news of Goldy, sent officially by cable, he must

be accepted as missing finally.

His death has proved a far greater shock to me than I

thought possible, since we came out of the line - probably due

to nerves.

I was proud to come out as fit as I did, but since then

I've had a very bad chest. I've kept going, however, and not

had to report sick, though I've been rather disturbed by having

three faints recently - fortunately only ^one in public, and then

among strange officers.

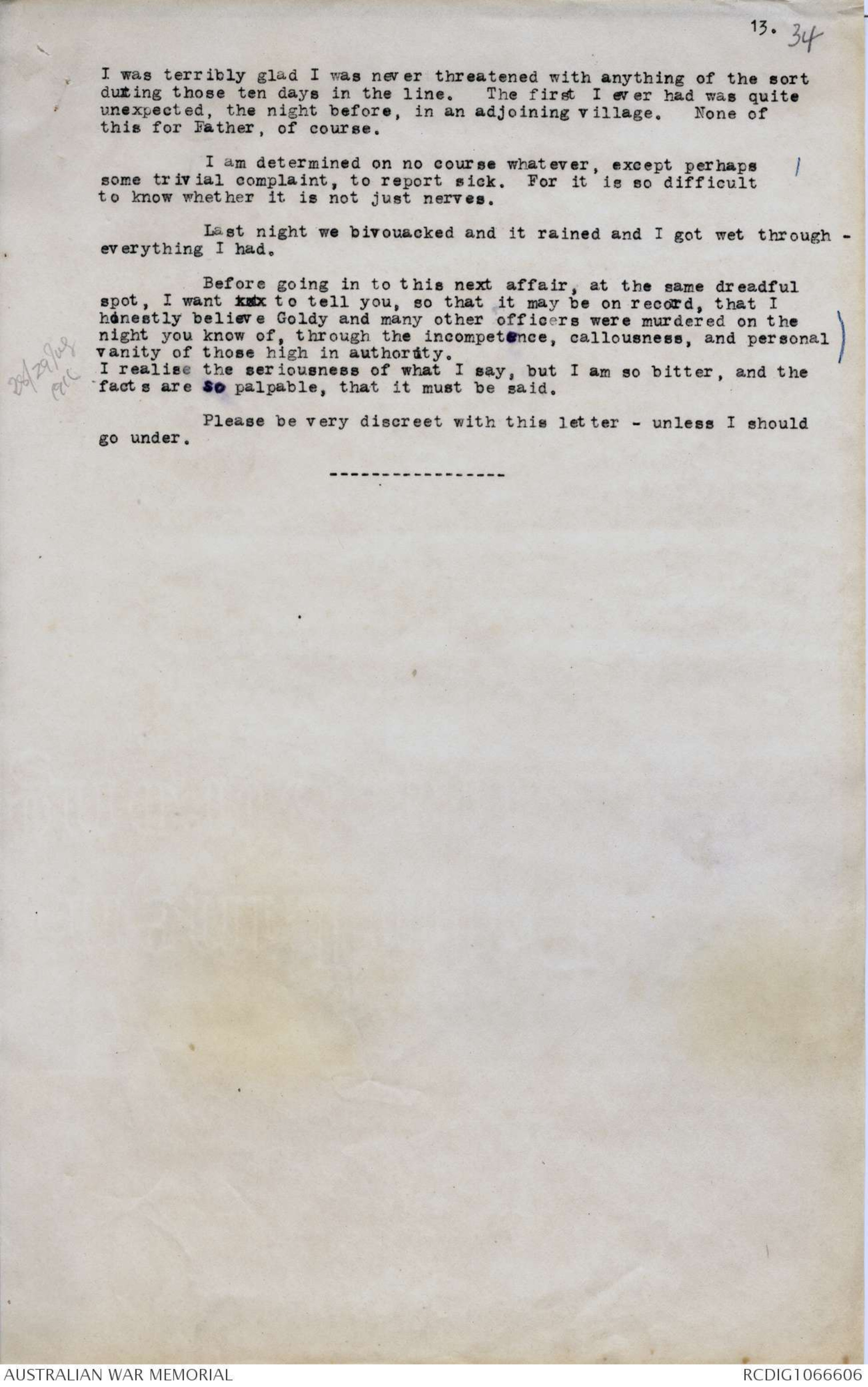

13. 34

I was terribly glad I was never threatened with anything of the sort

during those ten days in the line. The first I ever had was quite

unexpected, the night before, in an adjoining village. None of

this for Father, of course.

I am determined on no course whatever, except perhaps

some trivial complaint, to report sick. For it is so difficult

to know whether it is not just nerves.

Last night we bivouacked and it rained and I got wet through -

everything I had.

Before going in to this next affair, at the same dreadful

spot, I want xxx to tell you, so that it may be on record, that I

honestly believe Goldy and many other officers were murdered on the

night you know of, through the incompetence, callousness, and personal

vanity of those high in authority.

[*28/29 Aug

1916*] I realise the seriousness of what I say, but I am so bitter, and the

facts are so palpable, that it must be said.

Please be very discreet with this letter - unless I should

go under.

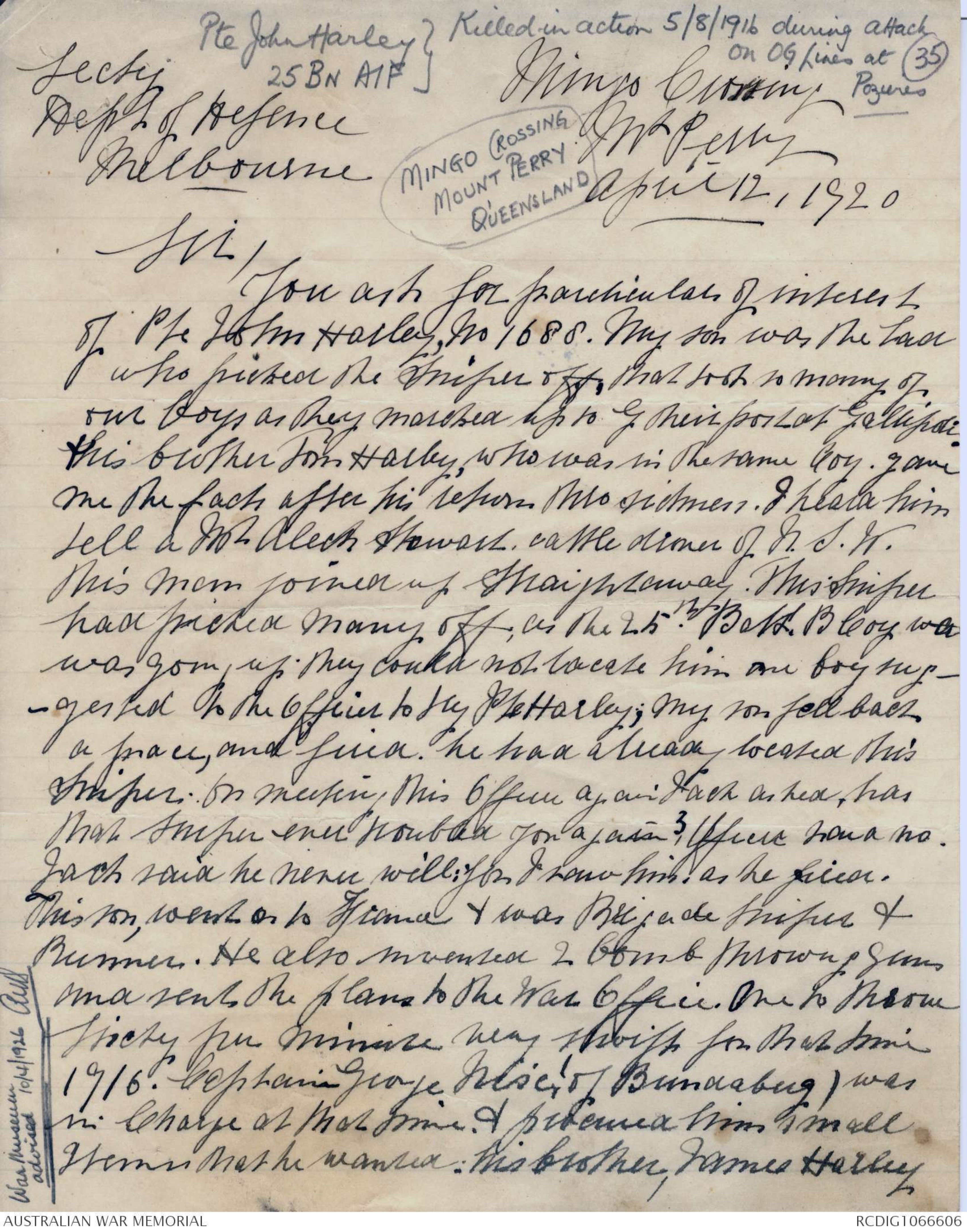

35

[*Pte John Harley 25BN AIF Killed in action 5/8/1916 during attack

on OG Lines at Pozieres*]

Secty

Dept of Defence

Melbourne

Mingo Crossing

Mt Perry

April 12, 1920

[*MINGO CROSSING

MOUNT PERRY

QUEENSLAND*]

Sir,

You ask for particulars of interest

of Pte John Harley, No 1688. My son was the lad

who picked the sniper off, that took so many of

our boys as they marched up to [[G?]] their post at Gallipoli.

His brother Tom Harley, who was in the same Coy. gave

me the facts after his return from sickness. I heard him

tell a Mr Alech Stewart, cattle drover of N.S.W.

this man joined up straight away. This Sniper

had picked many off, as the 25th Batt. B Coy was

was going up they could not locate him one boy

suggested to the officer to try Pte Harley; my son fell back

a pace, and fired. he had already located this

Sniper. On meeting this Officer again Jack asked, has

that Sniper ever troubled you again? Officer said no.

Jack said he never will; for I saw him: as he fired.

This son, went on to France & was Brigade Sniper &

Runner. He also invented 2 bomb throwing guns

and sent the plans to the War Office. One to throw

Sixty per minute very swift for that time

1916. Captain George [[Wisely?]] of Bundaberg) was

in Charge at that time. & secured him small

items that he wanted. His brother, James Harley

[*War Museum

advised 10/4/26 AWB*]

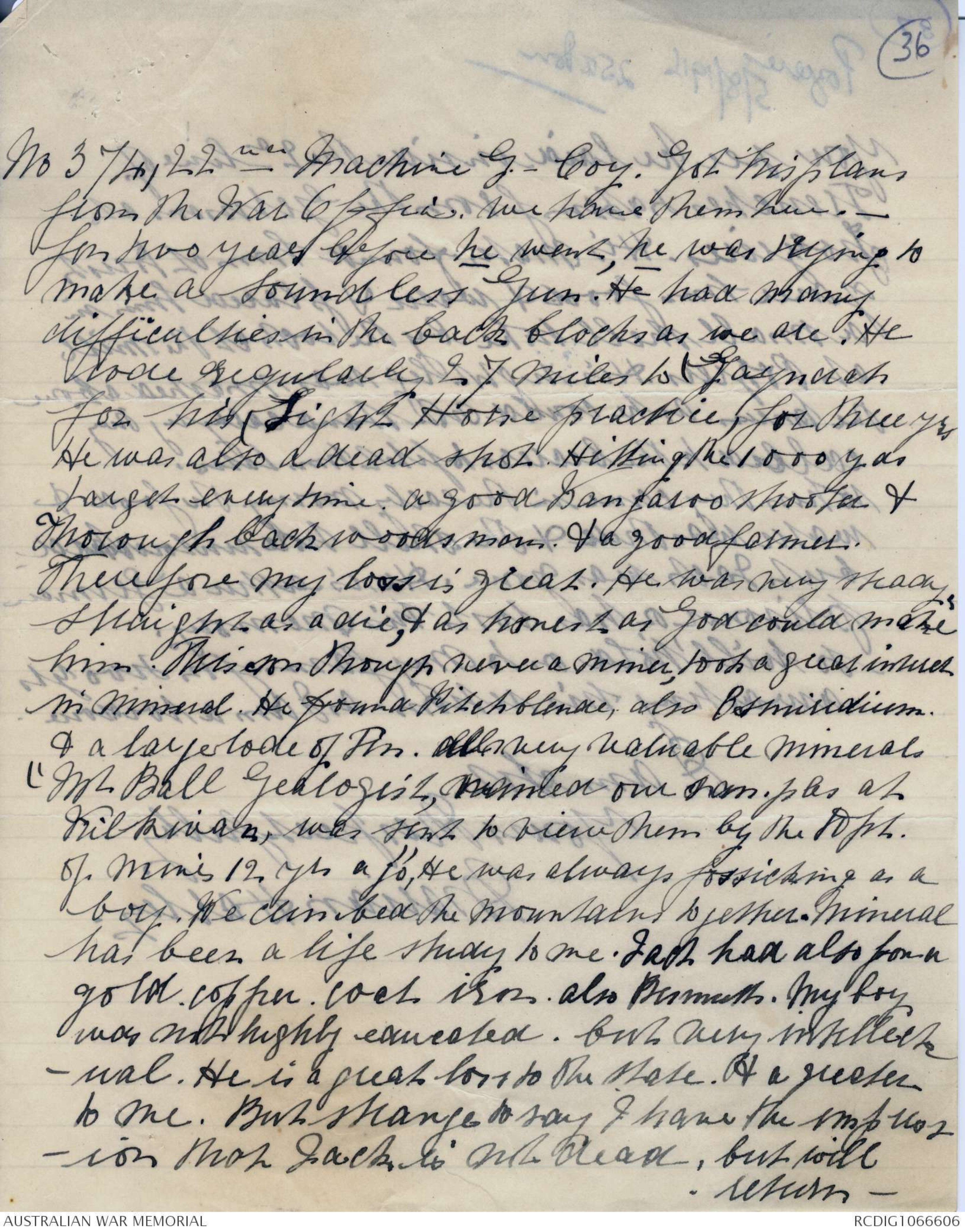

36

No 374, 22nd Machine G.- Coy. Got his plans

from the War Office. We have them here. -

for two years before he went, he was trying to

make a Soundless Gun. He had many

difficulties in the back blocks as we are. He

rode regularly 27 miles to Gayndah

for his Light Horse practice, for three yrs

He was also a dead shot. Hitting the 1000 yds

target every time. A good Kangaroo shooter &

thorough backwoods man. & a good farmer.

Therefore my loss is great. He was very steady,

straight as a die, & as honest as God could make

him. This son though never a miner, took a great interest

in Mineral. He found Pitchblende, also Osmiridium.

& a large lode of Tin. All very valuable minerals

"Mr Ball Geologist, viewed our samples at

Kilkivan, was sent to view them by the Dpt.

of Mines 12 yrs ago", He was always fossicking as a

boy. We climbed the mountains together. Mineral

has been a life study to me. Jack had also found

gold. copper. coal iron. also Bismuth. My boy

was not highly educated. but very intellectual.

He is a great loss to the state. & a greater

to me. But strange to say I have the impression

that Jack is not dead, but will

return -

37

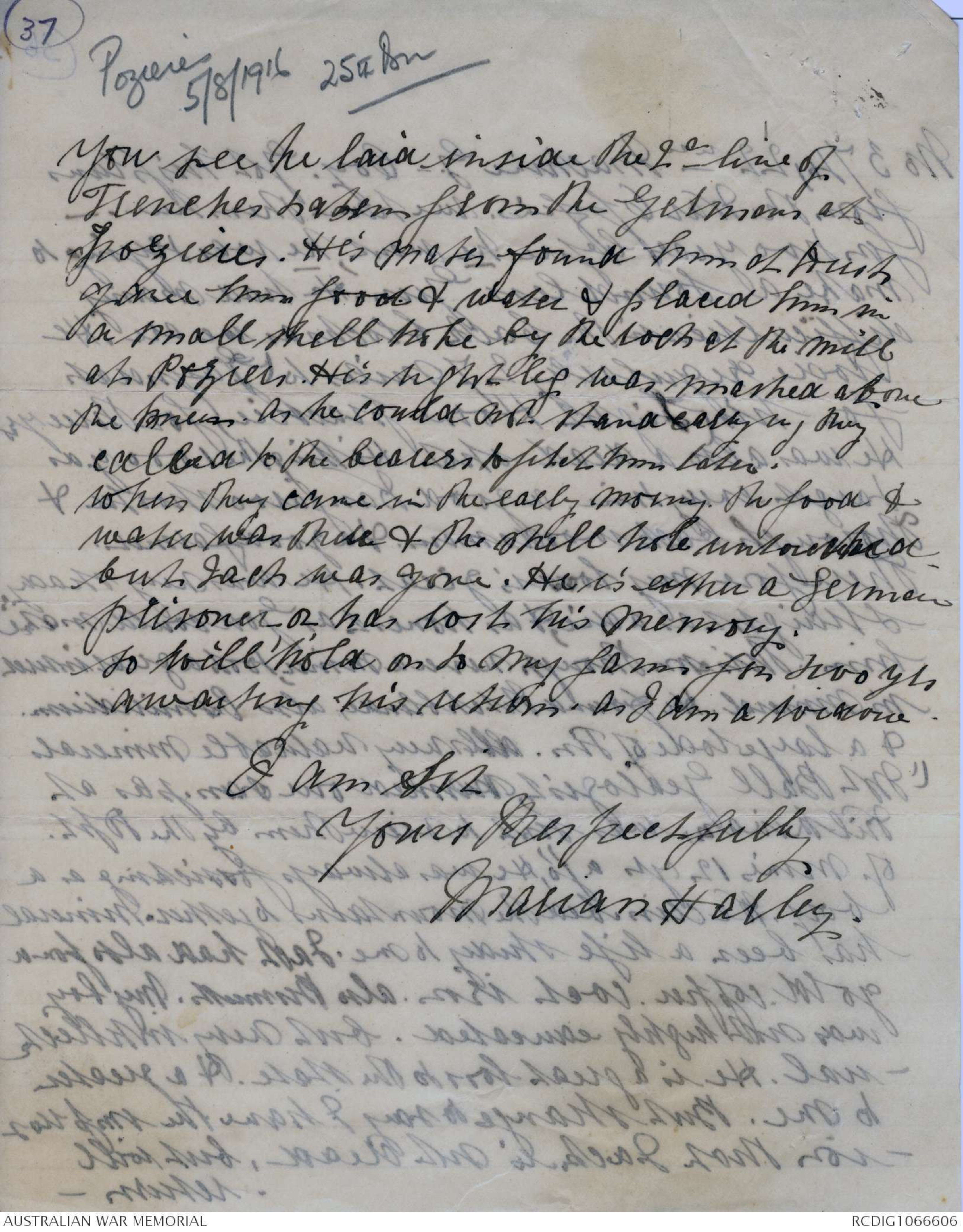

[*Pozieres

5/8/1916

25th Bn*]

you see he laid inside the 2nd line of

trenches taken from the Germans at

Pozieres. His mates found him on dusk

gave him food & water & placed him in

a small shell hole by the back of the mill

at Pozieres. His right leg was smashed above

the knee. As he could not stand easily, they

called to the bearers to fetch him later.

When they came in the early morning th food &

water was there & shell hole untouched

but Jack was gone. He is either a German

prisoner or has lost his memory.

So will hold on to my farm for two yrs

awaiting his return. As I am a widow.

I am Sir

Yours respectfully

Marian Harley.

38

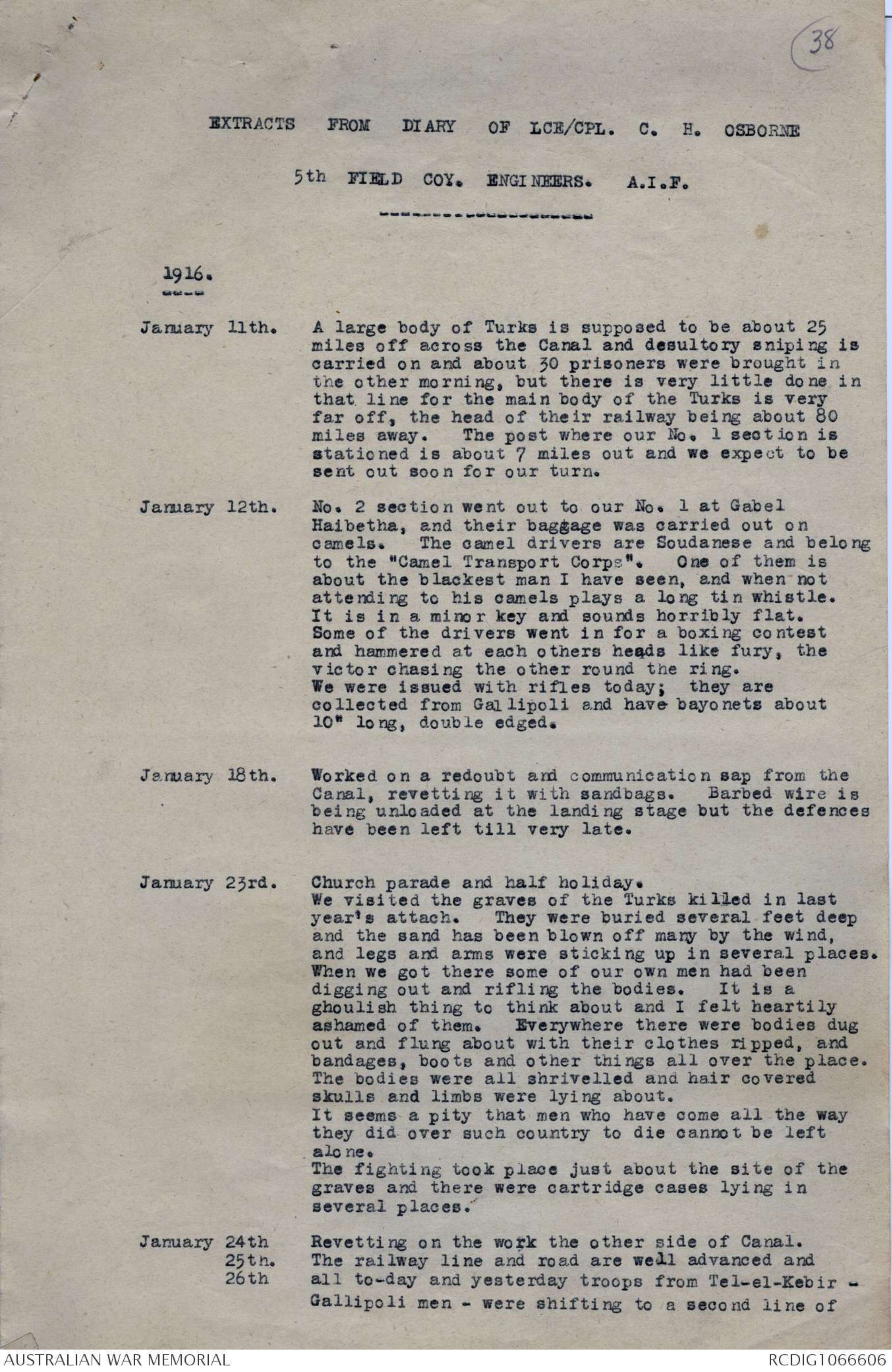

EXTRACTS FROM DIARY OF LCE/CPL. C. H. OSBORNE

5th FIELD COY. ENGINEERS. A.I.F.

1916.

January 11th. A large body of Turks is supposed to be about 25

miles off across the Canal and desultory sniping is

carried on and about 30 prisoners were brought in

the other morning, but there is very little done in

that line for the main body of the Turks is very

far off, the head of their railway being about 80

miles away. The post where our No. 1 section is

stationed is about 7 miles out and we expect to be

sent out soon for our turn.

January 12th. No. 2 section went out to our No. 1 at Gabel

Haibetha, and their baggage was carried out on

camels. The camel drivers are Soudanese and belong

to the "Camel Transport Corps". One of them is

about the blackest man I have seen, and when not

attending to his camels plays a long tin whistle.

It is in a minor key and sounds horribly flat.

Some of the drivers went in for a boxing contest

and hammered at each others heads like fury, the

victor chasing the other round the ring.

We were issued with rifles today; they are

collected from Gallipoli and have bayonets about

10" long, double edged.

January 18th. Worked on a redoubt and communication sap from the

Canal, revetting it with sandbags. Barbed wire is

being unloaded at the landing stage but the defences

have been left till very late.

January 23rd. Church parade and half holiday.

We visited the graves of the Turks killed in last

year's attach. They were buried several feet deep

and the sand has been blown off many by the wind,

and legs and arms were sticking up in several places.

When we got there some of our own men had been

digging out and rifling the bodies. It is a

ghoulish thing to think about and I felt heartily

ashamed of them. Everywhere there were bodies dug

out and flung about with their clothes ripped, and

bandages, boots and other things all over the place.

The bodies were all shrivelled and hair covered

skulls and limbs were lying about.

It seems a pity that men who have come all the way

they did over such country to die cannot be left

alone.

The fighting took place just about the site of the

graves and there were cartridge cases lying in

several places.

January 24th Revetting on the work the other side of Canal.

25th. The railway line and road are well advanced and

26th all to-day and yesterday troops from Tel-el-Kebir -

Gallipoli men - were shifting to a second line of

Maralyn K

Maralyn KThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.