Charles E W Bean, Diaries, AWM38 3DRL 606/244/1 - 1916 - 1933 - Part 3

[*19*]

- 2 -

Murdoch Mackay and Curnow were both Bendigo

men. Mackay had a fine career at the University of

Melbourne and later practised as a barrister.

[*20*]

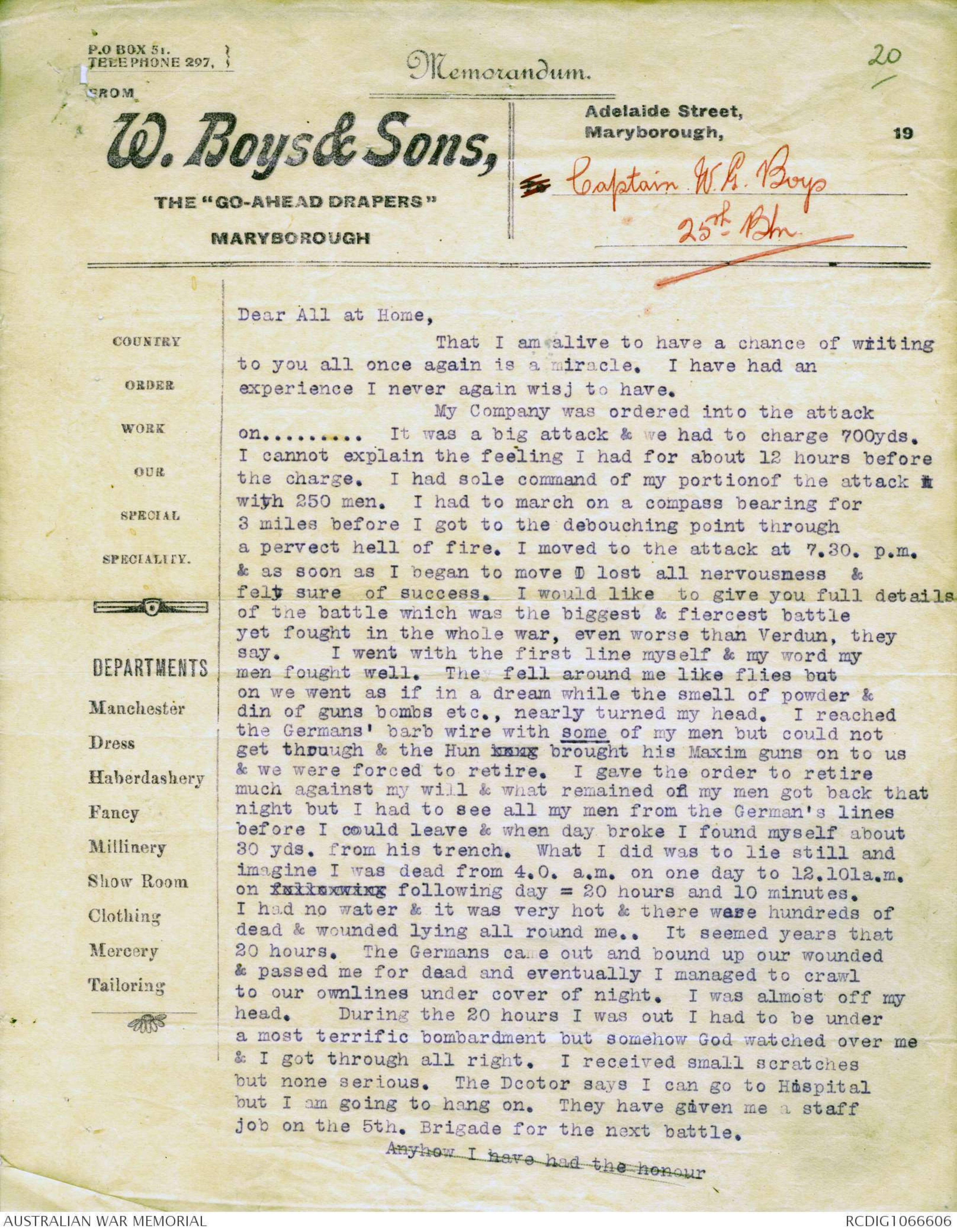

P.O. BOX 5,)

TELEPHONE 207, )

Memorandum.

FROM

W. Boys & Sons,

The "GO-AHEAD DRAPERS"

MARYBOROUGH

Adelaide Street,

Maryborough, 19To Captain W G Boys

25th Btn

[* COUNTRY ORDER WORK OUR SPECIAL SPECIALITY. DEPARTMENTS Manchester Dress Haberdashery Fancy Millinery Show Room Clothing Mercery Tailoring*]

Dear All at Home,

That I am alive to have a chance of wiriting

to you all once again is a miracle. I have had an

experience I never again wisj to have.

My Company was ordered into the attack

on....... It was a big attack & we had to charge 700yds.

I cannot explain the feeling I had for about 12 hours before

the charge. I had sole command of my portionof the attack w

wiyth 250 men. I had to march on a compass bearing for

3 miles before I got to the debouching point through

a pervect hell of fire. I moved to the attack at 7.30. p.m.

& as soon as I began to move OI lost all nervousness &

felt sure of success. I would like to give you full details

of the battle which was the biggest & fiercest battle

yet fought in the whole war, even worse than Verdun, they

say. I went with the first line myself & my word my

men fought well. they fell around me like flies but

on we went as if in a dream while the smell of powder &

din of guns bombs etc., nearly turned my head. I reached

the Germans' barb wire with some of my men but could not

get through & the Hun boug brought his Maxim guns on to us

& we were forced to retire. I gave the order to retire

much against my will & what remained of my men got back that

night but I had to see all my men from the German's lines

before I could leave & when day broke I found myself about

30 yds. from his trench. What I did was to lie still and

imagine I was dead from 4.0. a.m. on one day to 12.101a.m.

on fallowing following day = 20 hours and 10 minutes.

I had no water & it was very hot & there were hundreds of

dead & wounded lying all round me.. It seemed years that

20 hours. The Germans came out and bound up our wounded

& passed me for dead and eventually I managed to crawl

to our ownlines under cover of night. I was almost off my

head. During the 20 hours I was out I had to be under

a most terrific bombardment but somehow God watched over me

& I got through all right. I received small scratches

but none serious. The Doctor says I can go to Hospital

but I am going to hang on. They have given me a staff

job on the 5th. Brigade for the next battle.Anyhow I have had the honour

Sheet No. 2. 21

Anyhow I have had the honour of being

in the biggest battle in history & I expect to get a c

decoration out of it.

[*COUNTRY ORDER WORK OUR SPECIAL SPECIALITY. DEPARTMENTS Manchester Dress Haberdashery Fancy Millinery Show Room Clothing Mercery Tailoring*]

[*Hist. Notes 22*]

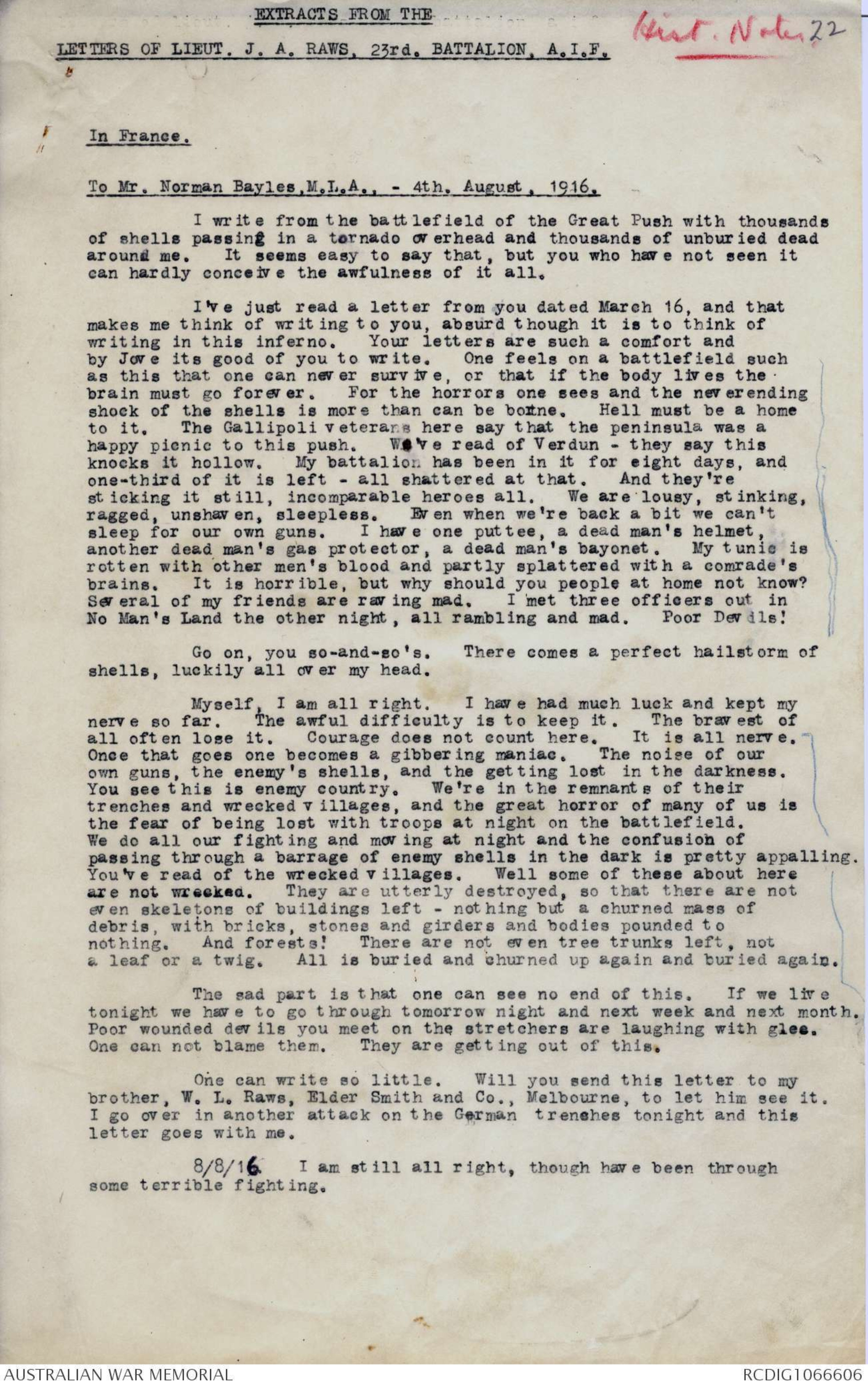

EXTRACTS FROM THE

LETTERS OF LIEUT. J. A. RAWS, 23rd BATTALION, A.I.F.

In France.

To Mr. Normal Bayles, M.L.A., - 4th August, 1916.

I write from the battlefield of the Great Push with thousands

of shells passing in a tornado overhead and thousands of unburied dead

around me. It seems easy to say that, but you who have not seen it

can hardly conceive the awfulness of it all.

I've just read a letter from you dated March 16, and that

makes me think of writing to you, absurd though it is to think of

writing in this inferno. Your letters are such a comfort and

by Jove its good of you to write. One feels on a battlefield such

as this that one can never survive, or that if the body lives the

brain must go forever. For the horrors ones sees and the never ending

shock of the shells is more than can be borne. Hell must be a home

to it. The Gallipoli veterans here say that the peninsula was a

happy picnic to this push. We've read of Verdun - they say this

knocks it hollow. My battalion has been in it for eight days, and

one-third of it is left - all shattered at that. And they're

sticking it still, incomparable heroes all. We are lousy, stinking,

ragged, unshaven, sleepless. Even when we're back a bit we can't

sleep for our own guns. I have one puttee, a dead man's helmet,

another dead man's gas protector, a dead man's bayonet. My tunic is

rotten with other men's blood and partly splattered with a comrade's

brains. It is horrible, but why should you people at home not know?

Several of my friends are raving mad. I met three officers out in

No Man's Land the other night, all rambling and mad. Poor Devils!

Go on, you so-and-so's. There comes a perfect hailstorm of

shells, luckily all over my head.

Myself, I am all right. I have had much luck and kept my

nerve so far. The awful difficulty is to keep it. The bravest of

all often lose it. Courage does not count here. It is all nerve.

Once that goes one becomes a gibbering maniac. The noise of our

own guns, the enemy's shells, and the getting lost in the darkness.

You see this is enemy country. We're in the remnants of their

trenches and wrecked villages, and the great horror of many of us is

the fear of being lost with troops at night on the battlefield.

We do all our fighting and moving at night and the confusion of

passing through a barrage of enemy shells in the dark is pretty appalling.

You've read of the wrecked villages. Well some of these about here

are not wrecked. They are utterly destroyed, so that there are not

even skeletons of buildings left - nothing but a churned mass of

debris, with bricks, stones and girders and bodies pounded to

nothing. And forests! There are not even tree trunks left, not

a leaf or a twig. All is buried and churned up again and buried again.

The sad part is that one can seen no end of this. If we live

tonight we have to go through tomorrow night and next week and next month.

Poor wounded devils you meet on the stretchers are laughing with glee.

One can not blame them. They are getting out of this.

One can write so little. Will you send this letter to my

brother, W.L. Raws, Elder Smith and Co., Melbourne, to let him see it.

I go over in another attack on the German trenches tonight and this

letter goes with me.

8/8/16 I am still all right, though have been through

some terrible fighting.

2.

[*23*]

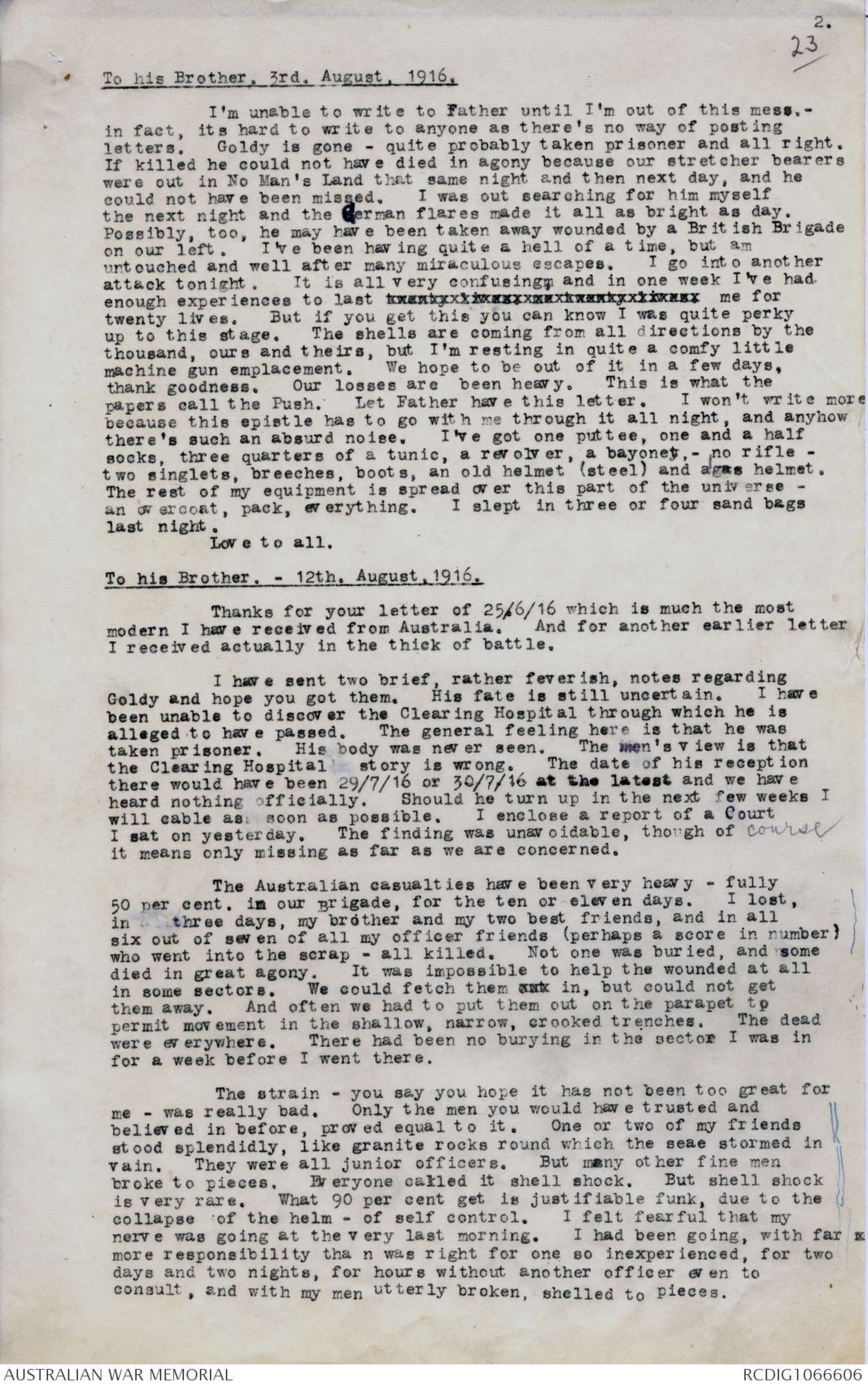

To his Brother, 3rd, August, 1916.

I'm unable to write to Father until I'm out of this mess.-

in fact, it's hard to write to anyone as there's no way of posting

letters. Goldy is gone - quite probably taken prisoner and all right.

If killed he could not have died in agony because our stretcher bearers

were out in No Man's Land that same night and then next day, and he

could not have been missed. I was out searching for him myself

the next night and the German flares made it all as bright as day.

Possibly, too, he may have been taken away wounded by a British Brigade

on our left. I've been having quite a hell of a time, but am

untouched and well after many miraculous escapes. I go into another

attack tonight. It is all very confusingm, and in one week I've had

enough experiences to last twentyxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxtwenty lives me for

twenty lives. But if you get this you can know I was quite perky

up to this stage. The shells are coming from all directions by the

thousand, ours and theirs, but I'm resting in quite a comfy little

machine gun emplacement. We hope to be out of it in a few days,

thank goodness. Our losses are been heavy. this is what the

papers call the Push. let Father have this letter. I won't write more

because this epistle has to go with me through it all night, and anyhow

there's such an absurb noise. I've got one puttee, one and a half

socks, three quarters of a tunic, a revolver, a bayonet, - no rifle -

two singlets, breeches, boots, an old helmet (steel) and agas helmet.

The rest of my equipment is spread over this part of the universe -

an overcoat, pack, everything. I slept in three or four sand bags

last night.

Love to all.

To his Brother. - 12th, August, 1916.

Thanks for your letter of 25/6/16 which is much the most

modern I have received from Australia. And for another earlier letter

I received actually in the thick of battle.

I have sent two brief, rather feverish, notes regarding

Goldy and hope you got them. His fate is still uncertain. I have

been unable to discover the Clearing Hospital through which he is

alleged to have passed. The general feeling here is that he was

taken prisoner. His body was never seen. The men's view is that

the Clearing Hospital story is wrong. The date of his reception

there would have been 29/7/16 or 30/7/16 at the latest and we have

heard nothing officially. Should he turn up in the next few weeks I

will cable as soon as possible. I enclose a report of a Court

I sat on yesterday. The finding was unavoidable, though of course

it means only missing as far as we are concerned.

The Australian casualties have been very heavy - fully

50 per cent, in our Brigade, for the ten or eleven days. I lost

in three days, my brother and my two best friends, and in all

six out seven of all of my officer friends (perhaps a score in number)

who went into the scrap - all killed. Not one was buried, and some

died in great agony. It was impossible to help the wounded at all

in some sectors. We could fetch them out in, but could not get

them away. And often we had to put them out on the parapet to

permit movement in the shallow, narrow crooked trenches. The dead

were everywhere. There had been no burying in the sector I was in

for a week before I went there.

The strain - you say you hope it has not been too great for

me - was really bad. Only the men you would have trusted and

believed in before, proved equal to it. One or two of my friends

stood splendidly, like granite rocks round which the seae stormed in

vain. They were all junior officers. But many other fine men

broke to pieces. Everyone called it shell shock. But shell shock

is very rare. What 90 per cent get is justifiable funk, due to the

collapse of the helm - of self control. I felt fearful that my

nerve was going at the very last morning. I had been going, with far x

more responsibility tha n was right for one so inexperienced, for two

days and two nights, for hours without another officer even to

consult, and with my men utterly broken, shelled to pieces.

3.

[*24*]

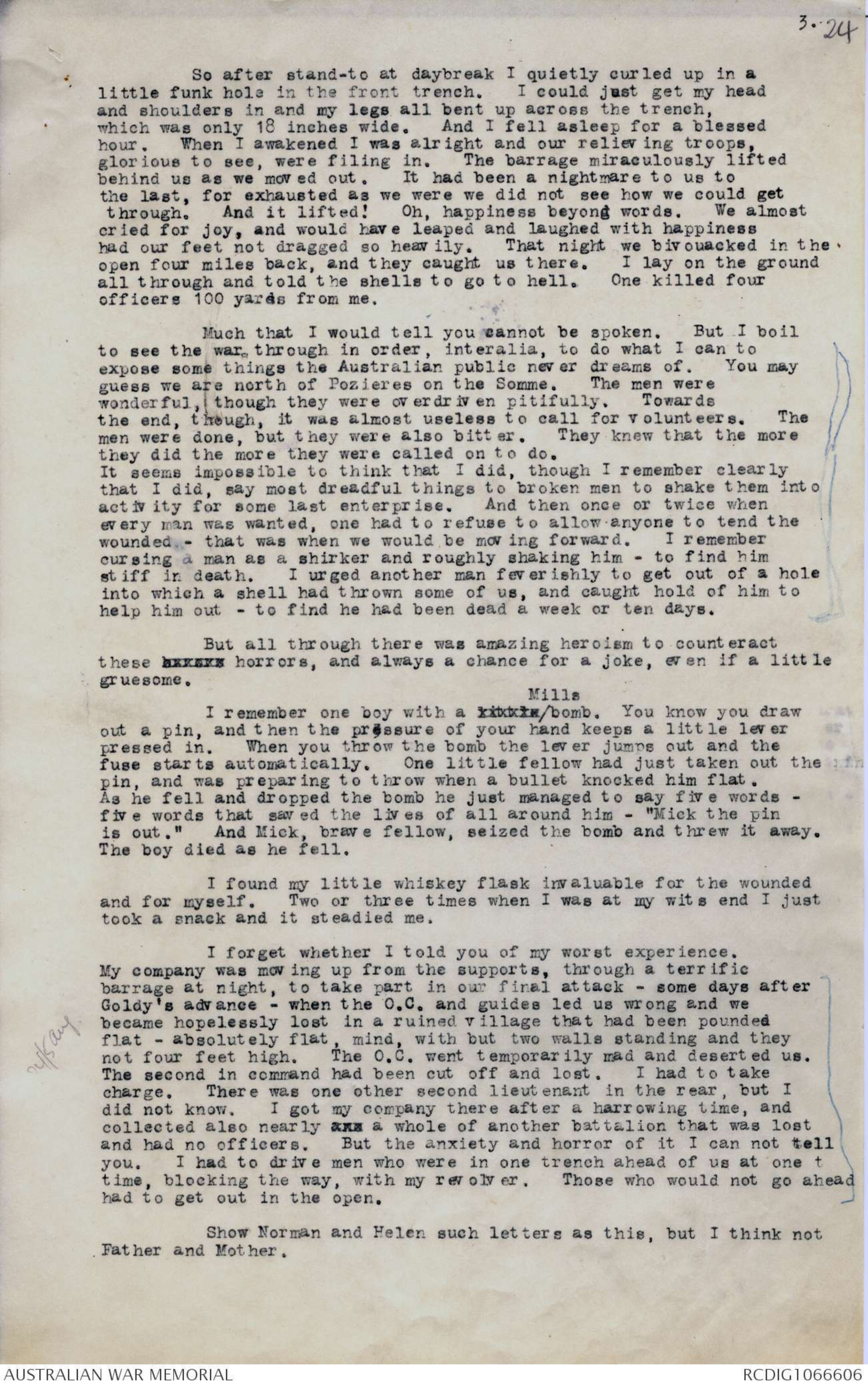

So after stand-to at daybreak I quietly caurled up in a

little funk hole in the front trench. I could just get my head

and shoulders in and my legs all bent up across the trench,

which was only 18 inches wide. And I fell asleep for a blessed

hour. When I awakened I was alright and our relieving troops,

glorious to see, were filing in. The barrage miraculously lifted

behind us as we moved out. It had been a nightmare to us to

the last, for exhausted as we were we did not see how we could get

through. And it lifted! Oh happiness beyond words. We almost

cried for joy, and would have leaped and laughed with happiness

had our feed not dragged so heavily. That night we bivouacked in the

open four miles back, and they caught us there. I lay on the ground

all through and told the shells to go to hell. One killed four

officers 100 yards from me.

Much that I would tell you cannot be spoken. But I boil

to see the war through in order, interalia, to do what I can to

expose some things the Australian public never dreams of. You may

guess we are north of Pozieres on the Somme. The men were

wonderful, though they were overdriven pitifully. Towards

the end, though, it was almost useless to call for volunteers. The

men were done, but they were also bitter. They knew that the more

they did the more they were called on to do.

It seems impossible to think that I did, though I remember clearly

that I did, say most dreadful things to broken men to shake them into

activity for some last enterprise. And then once or twice when

every man was wanted, one had to refuse to allow anyone to tend the

wounded - that was when we would be moving forward. I remember

cursing a man as a shirker and roughly shaking him - to find him

stiff in death. I urged another man feverishly to get out of a hole

into which a shell had thrown some of us, and caught hold of him to

help him out - to find he had been dead a week or ten days.

But all through there was amazing heroism to counteract

these horors horrors, and always a chance for a joke, even if a little

gruesome.

I remember one boy with a little^Mills bomb. You know you draw

out a pin, and then the pressure of your hand keeps a little lever

pressed in. When you throw the bomb the lever jumps out and the

fuse starts automatically. One little fellow had just taken out the

pin, and was preparing to throw when a bullet knocked him flat.

As he fell and dropped the bomb he just managed to say five words -

five words that saved the lives of all around him - "mick the pin

is out." And Mick, brace fellow, seized the bomb and threw it away.

The boy died as he fell.

I found my little whiskey flask invaluable for the wounded

and for myself. Two or three times when I was at my wits end I just

took a snack and it steadied me.

I forget whether I told you of my worst experience.

My company was moving up from the supports, through a terrific

barrage at night, to take part in our final attack - some days after

Goldy's advance - when the O.C. and guides led us wrong and we

[*?4/5 Aug*] became hopelessly lost in a ruined village that had been pounded

flat - absolutely flat, mind, with but two walls standing and they

not four feet high. The O.C. went temporarily mad and deserted us.

The second in command had been cut off and lost. I had to take

charge. There was one other second lieutenant in the rear, but I

did not know. I got my company there after a harrowing time, and

collected also nearly xxx a whole of another battalion that was lost

and had no officers. But the anxiety and horror of it I can not tell

you. I had to drive men who were in one trench ahead of us at one t

time, blocking the way, with my revolver. Those who would not go ahead

had to get out in the open.

Show Norman and Helen such letters as this, but I think not

Father and Mother.

4.

[*25*]

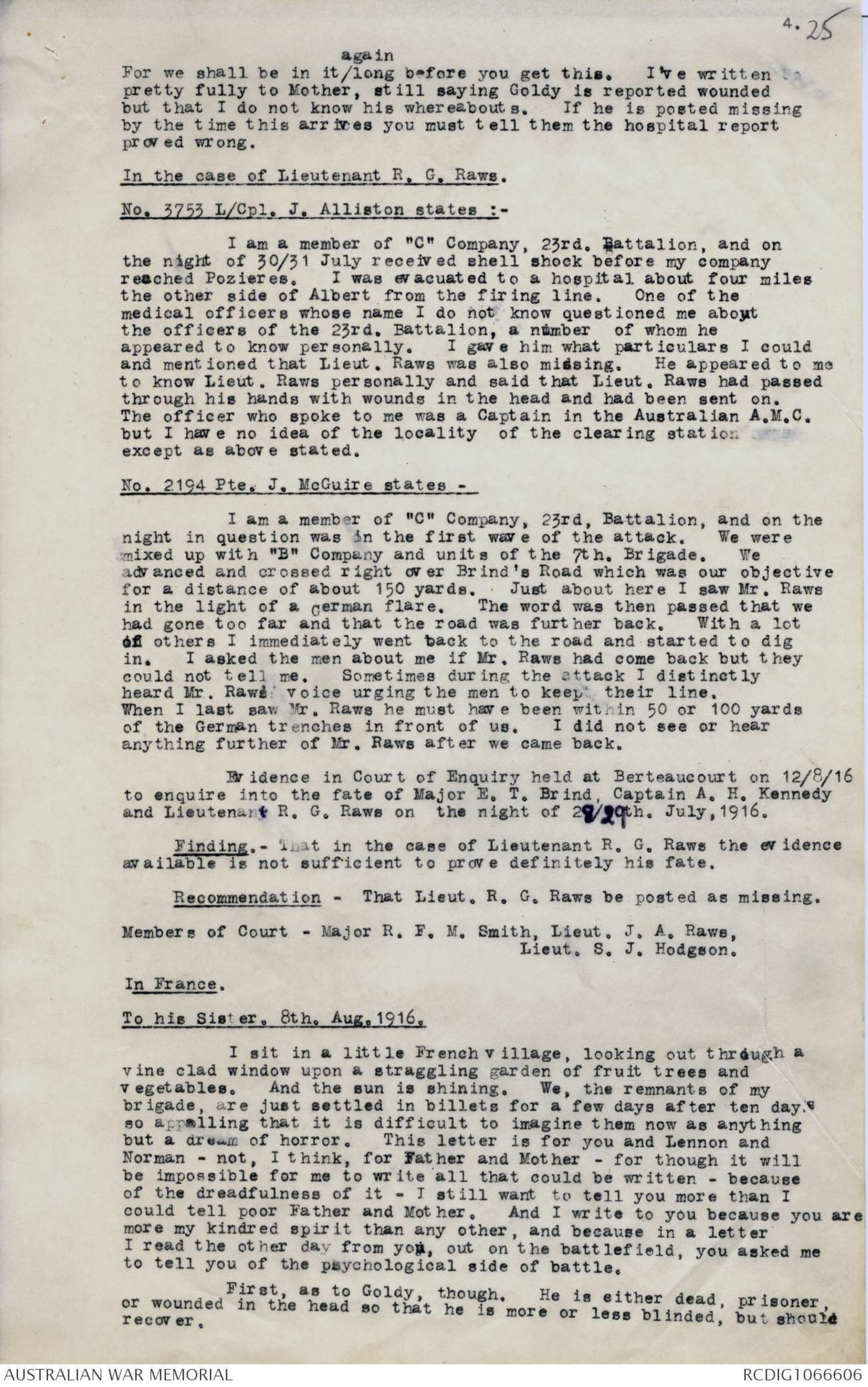

For we shall be in it ^again long before you get this. I've written

pretty fully to Mother, still saying Goldy is reported wounded

but that I do not know his whereabouts. If he is posted missing

by the time this arrives you must tell them the hospital report

proved wrong.

In the case of Lieutenant R. G. Raws.

No. 3753 L/Cpl. J. Alliston states:-

I am a member of "C" Company, 23rd. Battalion, and on

the night of 30/31 July received shell shock before my company

reached Pozieres. I was evacuated to a hospital about four miles

to other side of Albert from the firing line. One of the

medical officers whose name I do not know questioned me about

the officers of the 23rd. Battalion, a number of whom he

appeared to know personally. I gave him what particulars I could

and mentioned that Lieut. Raws was also missing. He appeared to me

to know Lieut. Raws personally and said that Lieut. Raws had passed

through his hands with wounds in the head and had been sent on.

The officer who spoke to me was a Captain in the Australian A.M.C.

but I have no idea of the locality of the clearing station

except as above stated.

No.2194 Pte. J. McGuire states-

I am a member of "C" Company, 23rd, Battalion, and one the

night in question was in the first wave of the attack. We were

mixed up with "B" Company and units of the 7th Brigade. We

advanced and crossed right over Brind's Road which was our objective

for a distance of about 150 yards. Just about here I saw Mr. Raws

in the light of a German flare. The word was then passed that we

had gone too far and that the road was further back. With a lot

of others I immediately went back to the road and started to dig

in. I asked the men about me if Mr. Raws had come back but they

could not tell me. Sometimes during the attack I distinctly

heard Mr. Raws voice urging the men to keep their line.

When I last saw Mr. Raws he must have been within 50 or 100 yards

of the German trenches in front of us. I did not see or hear

anything further of Mr. Raws after we came back.

Evidence in Court of Enquiry held at Berteaucourt on 12/8/16

to enquire into the fate of Major E. T. Brind, Captain, A. H. Kennedy

and Lieutenant R. G. Raws on the night of 28/29th. July, 1916.

Finding. - That in the case of Lieutenant R. G. Raws the evidence

available is not sufficient to prove definitely his fate.

Recommendation - That Lieut. R. G. Raws be posted as missing.

Members of Court - Major R. F. M. Smith, Lieut. J. A. Raws,

Lieut. S. J. Hodgson.

In France.

To his Sister, 8th. Aug. 1916.

I sit in a little French village, looking out through a

vine clad window upon a straggling garden of fruit trees and

vegetables. And the sun is shining. We, the remnants of my

brigade, are just settled in billet for a few days after ten days,

so appalling that it is difficult to imagine them now as anything

but a dream of horror. This letter is for you and Lennon and

Norman- not, I think, for Father and Mother - for though it will

be impossible for me to write all that could be written - because

of the dreadfulness of it - I still want to tell you more than I

could tell poor Father and Mother. And I write to you because you are

more my kindred spirit than any other, and because in a letter

I read the other day from you, out on the battlefield, you asked me

to tell you of the psychological side of battle.

First, as to Goldy, though. He is either dead, prisoner,

or wounded in the head so that he is more or less blinded, but should

recover.

5.

[*26*]

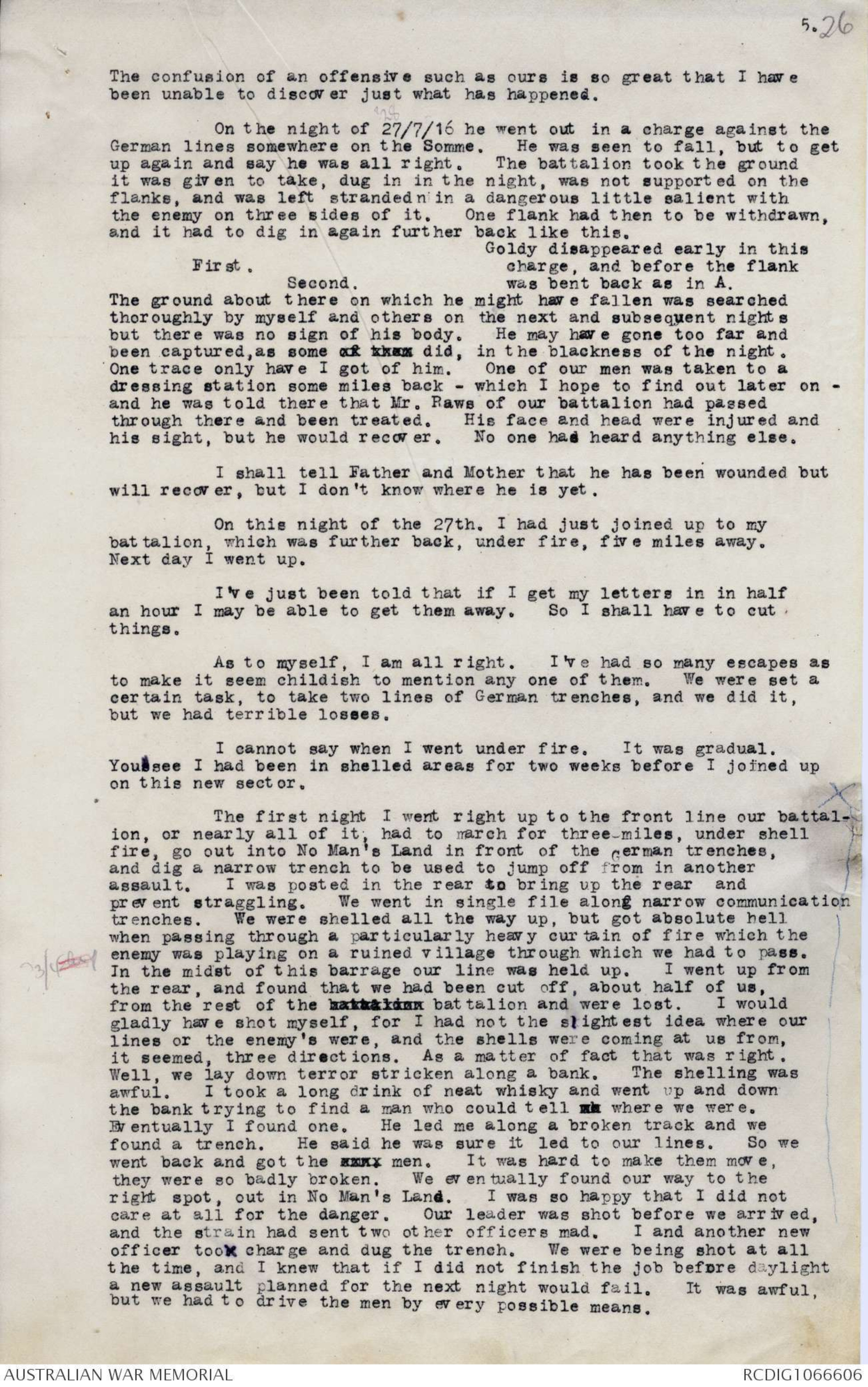

The confusion of an offensive such as ours is so great that I have

been unable to discover just what has happened.

On the night of 27^?28/7/16 he went out in a charge against the

German lines somewhere on the Somme. He was seen to fall, but to get

up again and say he was all right. The battalion took the ground

it was given to take, dug in in the night, was not supported on the

flanks, and was left stranded n in a dangerous little salient with

the enemy on three sides of it. One flank had then to be withdrawn,

and it had to dig in again further back like this.

Goldy disappeared early in this

First. charge, and before the flank

Second. was bent back as in A.

The ground about there on which he might have fallen was searched

thoroughly by myself and others on the next and subsequent nights

but there was no sign of his body. He may have gone too far and

been captured as some of them did, in the blackness of the night.

One trace only have I got of him. One of our men was taken to a

dressing station some miles back - which I hope to find out later on

and he was told there that Mr. Raws of our battalion had passed

through there and been treated. His face and head were injured and

his sight, but he would recover. No one had heard anything else.

I shall tell Father and Mother than he has been wounded but

will recover, but I don't know where he is yet.

On this night of the 27th. I had just joined up to my

battalion, which was further back, under fire, five miles away.

Next day I went up.

I've just been told that if I get my letters in in half

an hour I may be able to get them away. So I shall have to cut

things.

As to myself, I am all right. I've had so many escapes as

to make it seem childish to mention any one of them. We were set a

certain task, to take two lines of German trenches, and we did it,

but we had terrible loses.

I cannot say when I went under fire. It was gradual.

Youx see I had been in shelled areas for two weeks before I joined up

on this new sector.

The first night I went right up to the front line our battalion,

or nearly all of it, had to march for three miles, under shell

fire, go out into No Man's Land in front of the German trenches,

and dig a narrow trench to be used to jump off from in another

assault. I was posted in the rear to bring up the rear and

prevent straggling. We went in single file along narrow communication

trenches. We were shelled all the way up, but got absolute hell

when passing through a particularly heavy curtain of fire which the

[*?3/4 Aug] enemy was playing on a ruined village through which we had to pass.

In the midst of this barrage our line was held up. I went up from

the rear, and found that we had been cut off, about half of us,

from the rest of the battalion battalion and were lost. I would

gladly have shot myself, for I had not the slightest idea where our

lines or the enemy's were, and the shells were coming at us from,

it seemed, three directions. As a matter of fact that was right.

Well, we lay down terror stricken along a bank. The shelling was

awful. I took a long drink of neat whisky and went up and down

the bank trying to find a man who could tell xx where we were.

Eventually I found one. He led me along a broken track and we

found a trench. He said he was sure it led to our lines. So we

went back and got the xxxx men. It was hard to make them move,

they were so badly broken. We eventually found our way to the

right spot, out in No Man's Land. I was so happy that I did not

care at all for the danger. Our leader was shot before we arrived

and the strain had sent two other officers mad. I and another new

officer took charge and dug the trench. We were being shot at all

the time, and I knew that if I did not finish the job before daylight

a new assault planned for the next night would fail. It was awful,

but we had to drive the men by every possible means.

[*27*]

6.

And dig ourselves. The wounded and killed had to be thrown on one

side. I refused to let any sound man help a wounded man. The sound men

had to dig. Many men went mad.

Just before daybreak, an engineer officer out there, who

was hopelessly rattled, ordered us to go. The trench was not finished.

I took it on myself to insist on the men staying, saying that any man

who stopped digging would be shot. We dug on and finished amid a

tornado of shells, bursting shells. All the time, mind, the enemy

flares were making the whole area almost as light as day. We got away

as best we could. I was again in the rear going back, and again we

were cut off and lost. I was buried twice, and thrown down several

times - buried with dead and dying. The ground was covered with

bodies in all stages of decay and mutilation, and I would, after

struggling free from the earth, pick up a body by me to lift him out

with me, and find him a decayed corpse. I pulled a head off - was

covered with blood. The horror was indescribable. In the dim

mistly light of dawn I collected about 50 men and sent them off, mad with

terror, on the right track for home. Then two brave fellows stayed

behind and helped me with the only unburied wounded man we could find.

The journey down with him was awful. He was delirious. I tied one

of his legs to his pack with one of my puttees. On the way down

I found another man and made him stay and help us. It was so terribly

slow!

We got down to the first dressing station. There I met another

of our men who was certain that his cobber was lying wounded in that

barrage of fire. I would have given my immortal soul to get out of it,

but I simply had to go back with him and a stretcher bearer. We

spent two hours in that devastated village looking for wounded.

But all were dead. The sights I saw during that search, and the

smell, can I know never be exceeded by anything else the war may show me.

I went up again the next night and stayed up there. We were

shelled to hell ceaselessly. My company commander went mad and

[*?4/5 Aug*] disappeared. I and another officer who arrived with me did duty

with others.

The barrage behind us grew worse every day, cutting us

off from our supplies. We hung on, until eventually we were relieved

on 6/8/16.

I've told you hardly anything. There is so much to say.

My nerve lasted all right and my constitution. I had not even a

coat and we had no dug outs. I got water and biscuits from a German

body.

I saw many of my friends die.

c The post is off. Good luck.

To his Sister - 8th. Aug. 1916.

I sent away a brief note to you yesterday, but may not have

got it. In that I made reference to Goldy's wounds. I have not yet

been able to find out where he is. You see, we have been in severe

action for ten days, and in an offensive of this kind, you can

understand that one's time actual world is very limited. I was quite

close to Goldy, on that same section of the battlefield, but did not

see him. He fell very early, in the first charge across which led off

across open country to German lines. I was not there until next day.

Our Brigade went straight up from resting, through a considerable

bombardment, reached our lines, climbed out over the parapet, and

lay down in the open in front of the trench. It was our job to charge

across a certain section, reach a road, and there dig in, while troops

on our right were to go over at the same time, and occupy a line of

German trenches on our right.

[*28*]

7.

Diagram - see original document

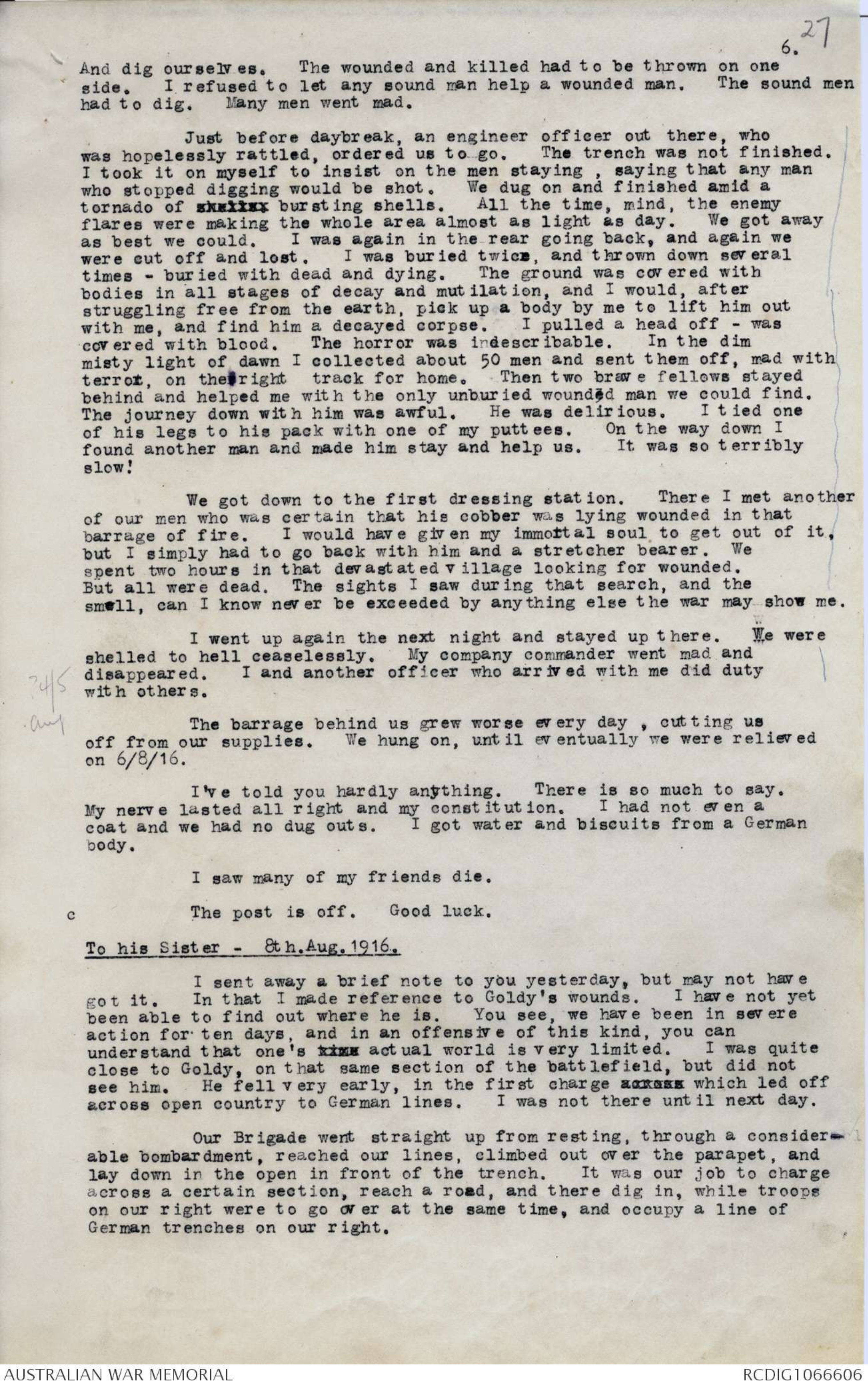

We went across at midnight, and had great difficulty in

discovering the road. Many went past it. The troops on our right

failed to take the trenches opposite them, and retired though some of

them came over towards us, and became mixed up with us. We dug

in almost half way across the wood, and found our position terribly

awkward. Our flank "A" was exposed to the Germans on our right

and the other "B" to the Germans on our left. We managed to dig

round on our left, and line up with British troops there, and then

we had to withdraw our right from "A", back almost at a right angle,

and dig back to our old line at "C". When I arrived next day, the

29th. July, our position was B.A.C. and you can see how terribly open

we were to the German fire. To make our position worse, the Germans

were able to establish a barrage of heavy continuous fire behind us,

which destroyed our communication trenches for bringing troops up,

and made communication very difficult. Thus to get up to

Diagram - see original document

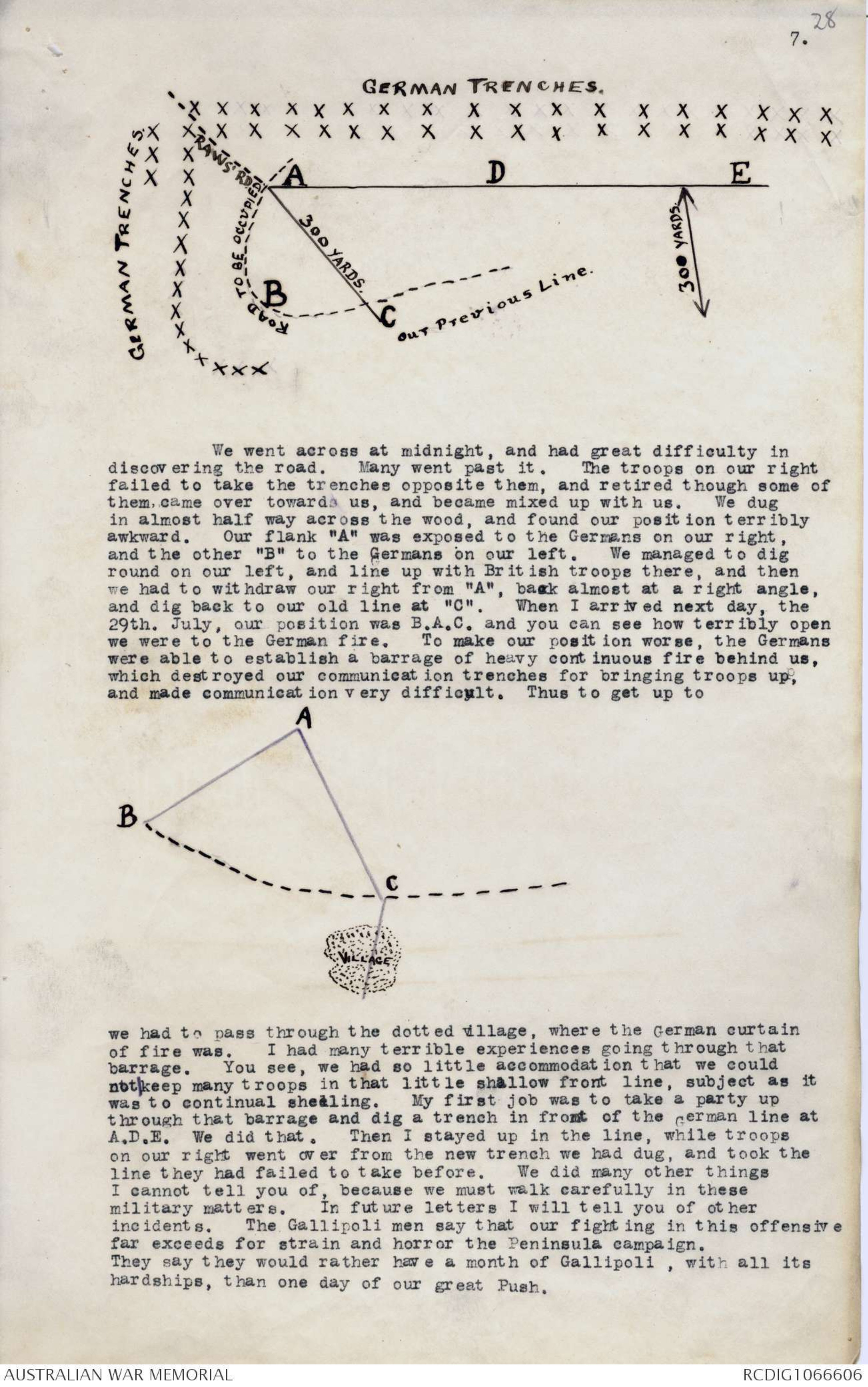

we had to pass through the dotted village, where the German curtain

of fire was. I had many terrible experiences going through that

barrage. You see, we had so little accommodation that we could

not keep many troops in that little shallow front line, subject as it

was to continual shelling. My first job was to take a party up

through that barrage and dig a trench in front of the German line at

A.D.E. We did that. Then I stayed up in the line, while troops

on our right went over from the new trench we had dug, and took the

line they had failed to take before. We did many other things

I cannot tell you of, because we must walk carefully in these

military matters. In future letters I will tell you of others

incidents. The Gallipoli men say that our fighting in this offensive

far exceeds for strain and horror the Peninsula campaign.

They say they would rather have a month of Gallipoli, with all its

hardships, than one day of our great Push.

Deb Parkinson

Deb ParkinsonThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.