Charles E W Bean, Diaries, AWM38 3DRL 606/243A/1 - 1916 - 1934 - Part 7

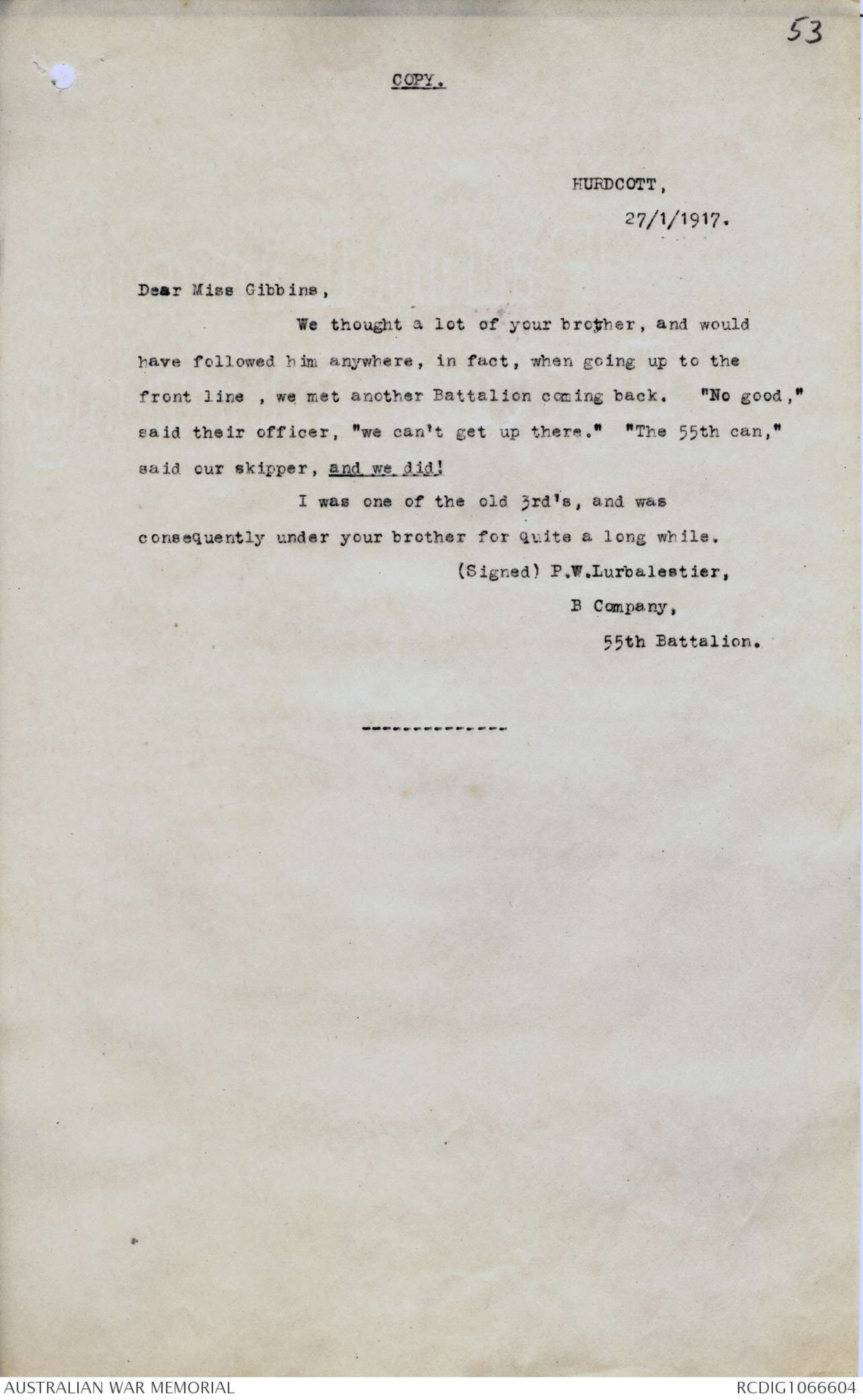

53

COPY.

HURDCOTT,

27/1/1917.

Dear Miss Gibbins,

We thought a lot of your brother, and would

have followed him anywhere, in fact, when going up to the

front line, we met another Battalion coming back. "No good,"

said their officer, "we can't get up there." "The 55th can,”

said our skipper, and we did!

I was one of the old 3rd's, and was

consequently under your brother for quite a long while.

(Signed) P.W.Lurbalestier,

B Company,

55th Battalion.

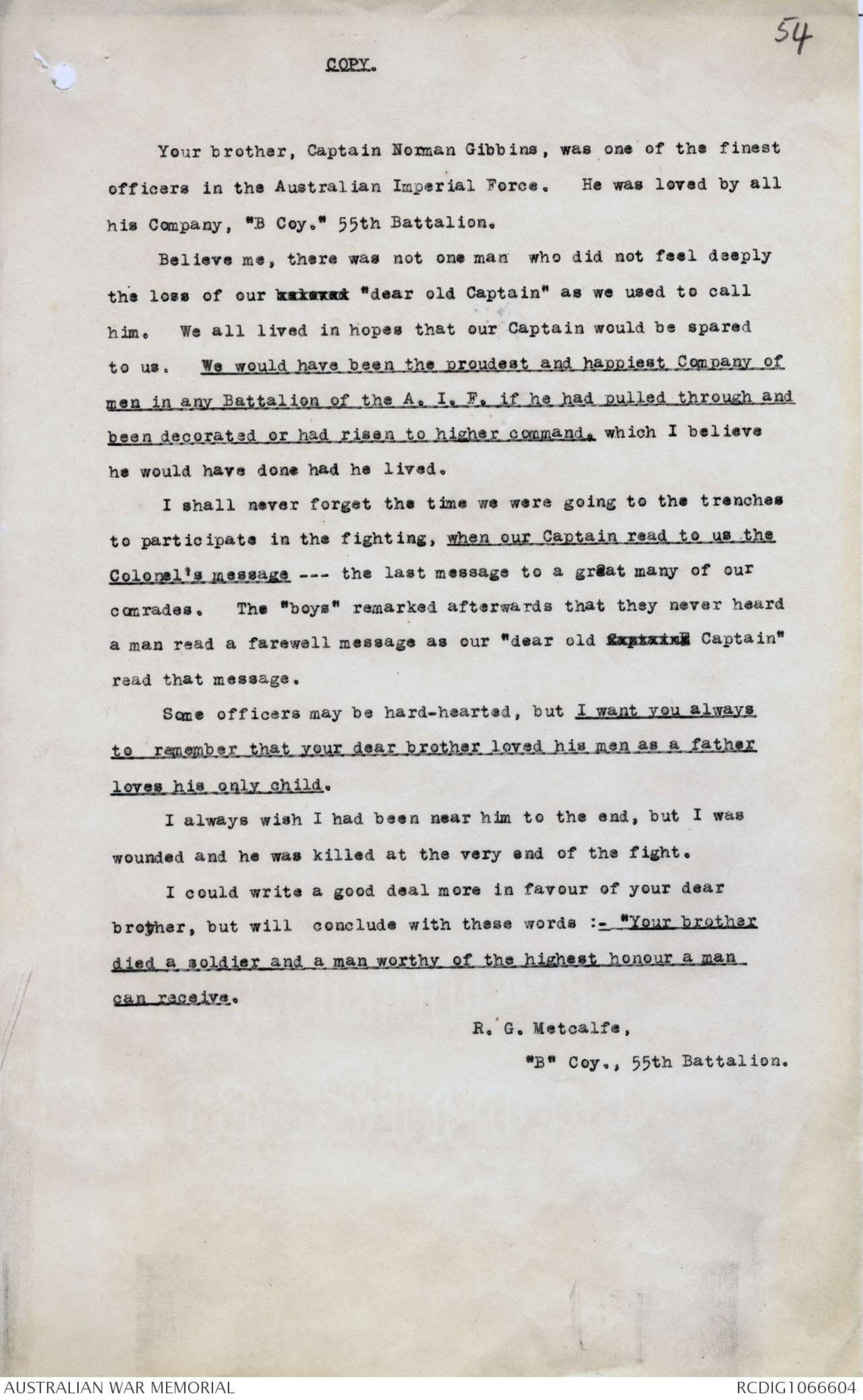

54

COPY.

Your brother, Captain Norman Gibbins, was one of the finest

officers in the Australian Imperial Force. He was loved by all

his Company, "B Coy." 55th Battalion.

Believe me, there was not one man who did not feel deeply

the loss of our beloved "dear old Captain" as we used to call

him. We all lived in hopes that our Captain would be spared

to us. We would have been the proudest and happiest Company of

men in any Battalion of the A. I. F. if he had pulled through and

been decorated or had risen to higher command, which I believe

he would have done had he lived.

I shall never forget the time we were going to the trenches

to participate in the fighting, when our Captain read to us the

Colonel's message –-- the last message to a great many of our

comrades. The "boys" remarked afterwards that they never heard

a man read a farewell message as our "dear old Captainx Captain"

read that message.

Some officers may be hard-hearted, but I want you always

to remember that your dear brother loved his men as a father

loves his only child.

I always wish I had been near him to the end, but I was

wounded and he was killed at the very end of the fight.

I could write a good deal more in favour of your dear

brother, but will conclude with these words :- "Your brother

died a soldier and a man worthy of the highest honour a man

can receive.

R. G. Metcalfe,

"B" Coy., 55th Battalion.

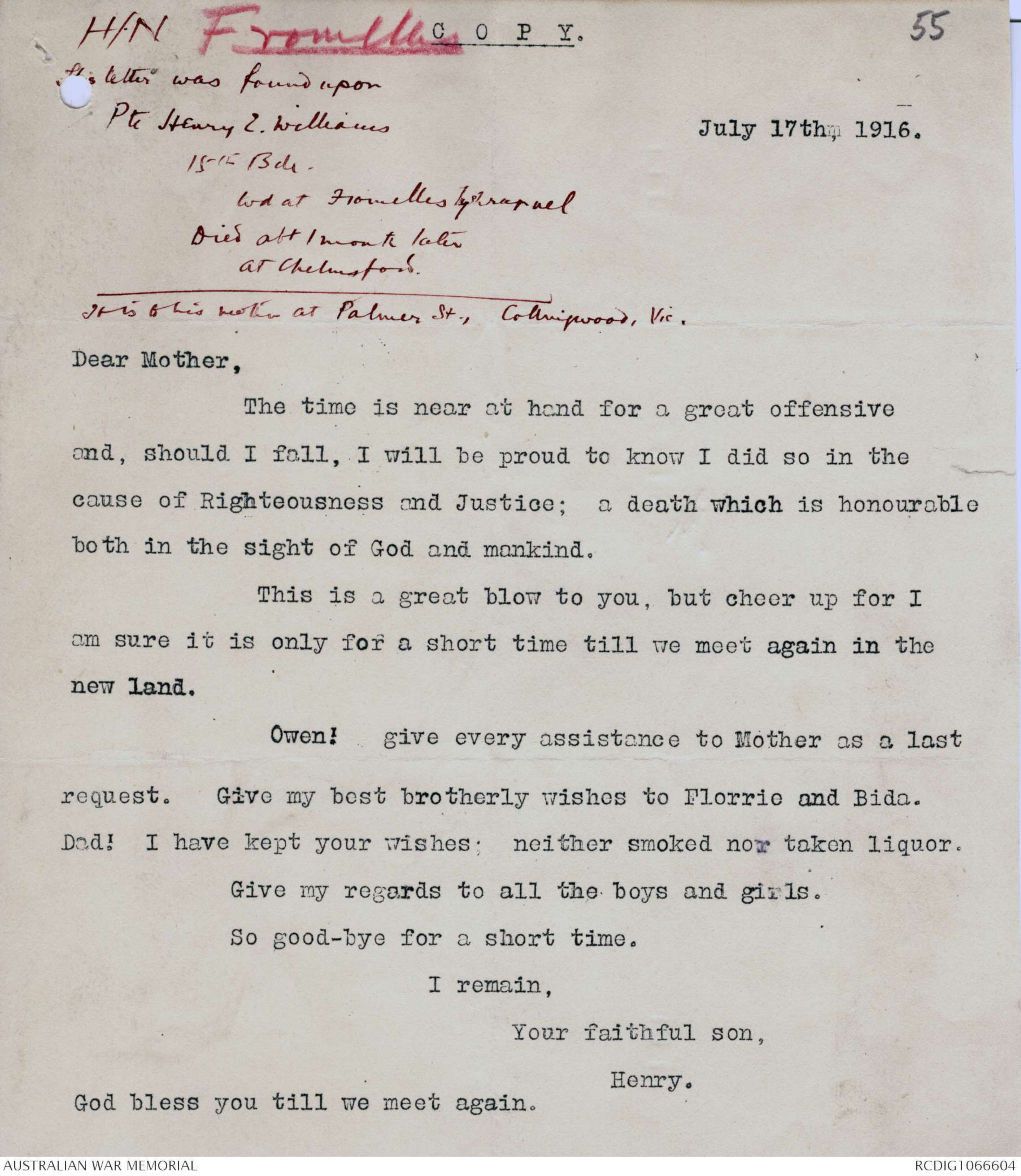

55

[*H/N Fromelles*]

COPY.

[*This letter was found upon

Pte Henry E. Williams

15th Bde

Wd at Fromelles by shrapnel

Died abt 1 month later

at Chelmsford

It is to his mother at Palmer St., Collingwood, Vic.*]

July 17th, 1916

Dear Mother,

The time is near at hand for a great offensive

and, should I fall, I will be proud to know I did so in the

cause of Righteousness and Justice; a death which is honourable

both in the sight of God and mankind.

This is a great blow to you, but cheer up for I

am sure it is only for a short time till we meet again in the

new land.

Owen! give every assistance to Mother as a last

request. Give my best brotherly wishes to Florrie and Bida.

Dad! I have kept your wishes; neither smoked nor taken liquor.

Give my regards to all the boys and girls.

So good-bye for a short time.

I remain,

Your faithful son,

Henry.

God bless you till we meet again.

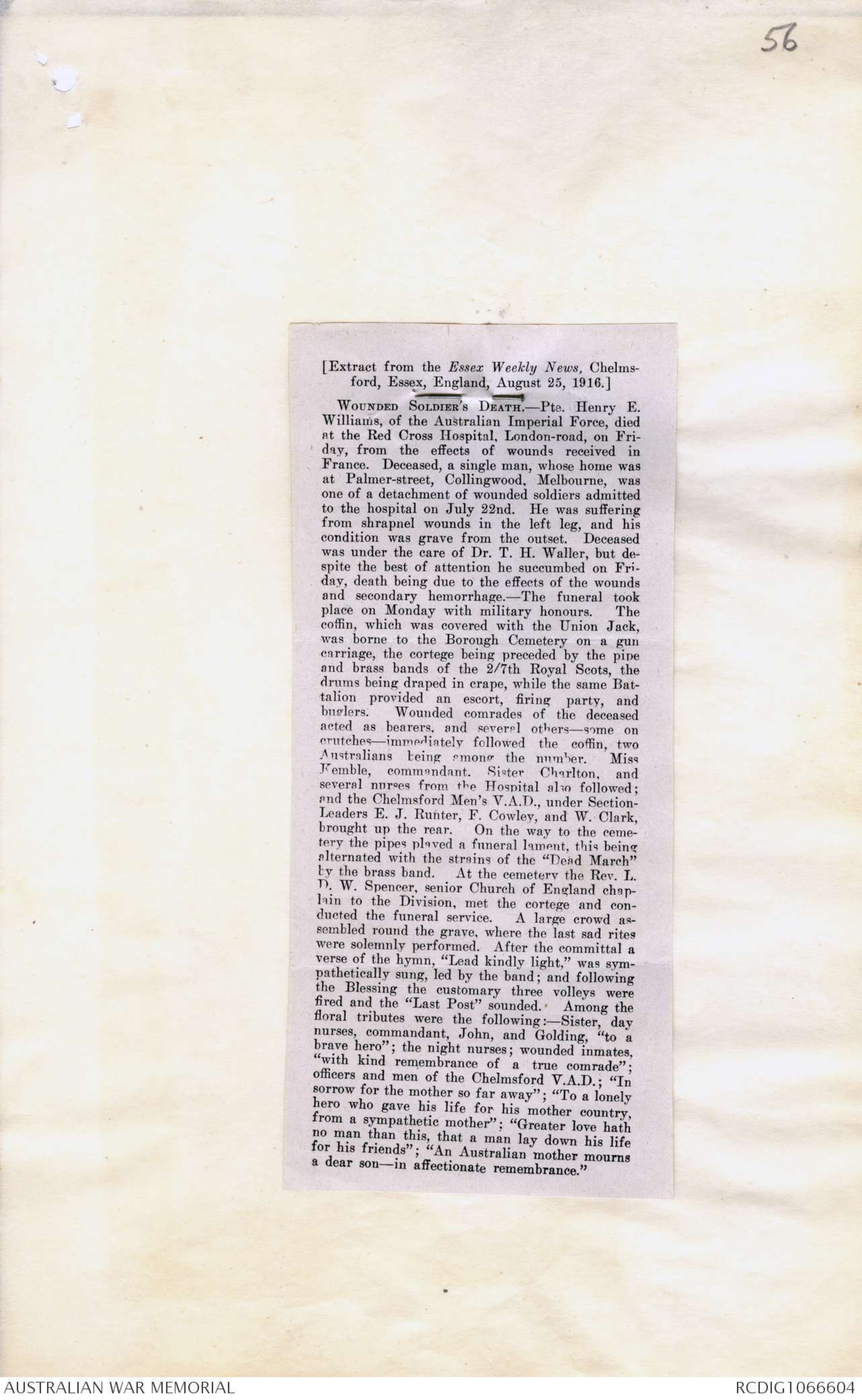

56

[Extract from the Essex Weekly News, Chelmsford,

Essex, England, August 25, 1916.]

WOUNDED SOLDIERS DEATH.--Pte. Henry E.

Williams, of the Australian Imperial Force, died

at the Red Cross Hospital. London-road, on Friday,

from the effects of wounds received in

France. Deceased, a single man, whose home was

at Palmer-street, Collingwood. Melbourne, was

one of a detachment of wounded soldiers admitted

to the hospital on July 22nd. He was suffering

from shrapnel wounds in the left leg, and his

condition was grave from the outset. Deceased

was under the care of Dr. T. H. Waller, but despite

the best of attention he succumbed on Friday,

death being due to the effects of the wounds

and secondary hemorrhage. -The funeral took

place on Monday with military honours. The

coffin, which was covered with the Union Jack,

was borne to the Borough Cemetery on a gun

carriage, the cortege being preceded by the pipe

and brass bands of the 2/7th Royal Scots, the

drums being draped in crape, while the same Battalion

provided an escort, firing party, and

buglers. Wounded comrades of the deceased

acted as bearers, and several others —some on

crutches — immediately followed the coffin, two

Australians being among the number. Miss

Kemble, commandant. Sister Charlton, and

several nurses from the Hospital also followed;

and the Chelmsford Men's V. A.D., under Section-Leaders

E. J. Runter, F. Cowley, and W. Clark,

brought up the rear. On the way to the cemetery

the pipes played a funeral lament, this being

alternated with the strains of the "Dead March"

by the brass band. At the cemetery the Rev. L.

D. W. Spencer, senior Church of England chaplain

to the Division, met the cortege and conducted

the funeral service. A large crowd assembled

round the grave, where the last sad rites

were solemnly performed. After the committal a

verse of the hymn, "Lead kindly light," was sympathetically

sung, led by the band; and following

the Blessing the customary three volleys were

fired and the "Last Post" sounded. Among the

floral tributes were the following:— Sister, day

nurses, commandant, John, and Golding, "to a

brave hero"; the night nurses; wounded inmates,

"with kind remembrance of a true comrade";

officers and men of the Chelmsford V.A.D.; "In

sorrow for the mother so far away"; "To a lonely

hero who gave his life for his mother country,

from a sympathetic mother"; "Greater love hath

no man than this, that a man lay down his life

for his friends"; "An Australian mother mourns

a dear son - in affectionate remembrance."

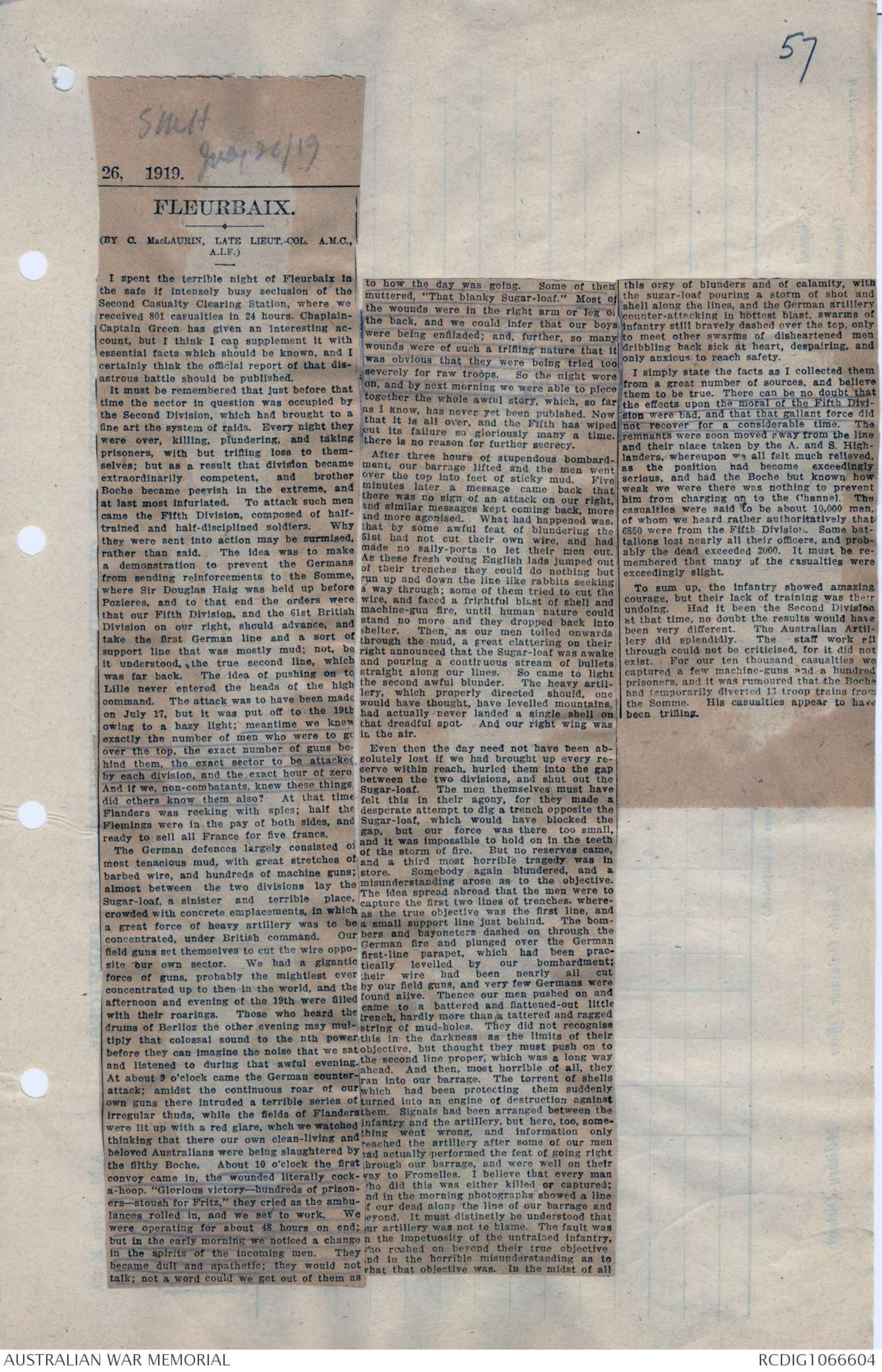

57

[*SMH

July 26/19*]

26, 1919. July 26/19

FLEURBAIX.

(BY C. MacLAURIN, LATE LIEUT.-COL A.M.C.,

A.I.F)

I spent the terrible night of Fleurbaix in

the safe if intensely busy seclusion of the

Second Casualty Clearing Station, where we

received 801 casualties in 24 hours. Chaplain-Captain

Green has given an interesting account,

but I think I can supplement it with

essential facts which should be known, and I

certainly think the official report of that disastrous

battle should be published.

It must be remembered that just before that

time the sector in question was occupied by

the Second Division, which had brought to a

fine art the system of raids. Every night they

were over, killing, plundering, and taking

prisoners, with but trifling loss to themselves;

but as a result that division became

extraordinarily competent, and brother

Boche became peevish in the extreme, and

at last most infuriated. To attack such men

came the Fifth Division, composed of half-trained

and half-disciplined soldiers. Why

they were sent into action may be surmised,

rather than said. The idea was to make

a demonstration to prevent the Germans

from sending reinforcements to the Somme,

where Sir Douglas Haig was held up before

Pozieres, and to that end the orders were

that our Fifth Division, and the 61st British

Division on our right, should advance, and

take the first German line and a sort of

support line that was mostly mud; not, be

it understood, the true second line, which

was far back. The idea of pushing on to

Lille never entered the heads of the high

command. The attack was to have been made

on July 17, but it was put off to the 19th

owing to a hazy light; meantime we knew

exactly the number of men who were to go

over the top, the exact number of guns behind

them, the exact sector to be attacked

by each division, and the exact hour of zero.

And if we, non-combatants, knew these things

did others know them also? At that time

Flanders was reeking with spies; half the

Flemings were in the pay of both sides, and

ready to sell all France for five francs.

The German defences largely consisted of

most tenacious mud, with great stretches of

barbed wire, and hundreds of machine guns;

almost between the two divisions lay the

Sugar-loaf, a sinister and terrible place,

crowded with concrete emplacements in which

a great force of heavy artillery was to be

concentrated, under British command. Our

field guns set themselves to cut the wire opposite

our own sector. We had a gigantic

force of guns, probably the mightiest ever

concentrated up to then in the world, and the

afternoon and evening of the 19th were filled

with their roarings. Those who heard the

drums of Berlioz the other evening may multiply

that colossal sound to the nth power

before they can imagine the noise that we sat

and listened to during that awful evening.

At about 9 o'clock came the German counter-attack;

amidst the continuous roar of our

own guns there intruded a terrible series of

irregular thuds, while the fields of Flanders

were lit up with a red glare, which we watched

thinking that there our own clean-living and

beloved Australians were being slaughtered by

the filthy Boche. About 10 o'clock the first

convoy came in, the wounded literally cock-a-hoop.

"Glorious victory—hundreds of prisoners—

stoush for Fritz," they cried as the ambulances

rolled in, and we set to work. We

were operating for about 48 hours on end;

but in the early morning we noticed a change

in the spirits of the incoming men. They

became dull and apathetic; they would not

talk; not a word could we get out of them as

to how the day was going. Some of them

muttered, "That blanky Sugar-loaf." Most of

the wounds were in the right arm or leg or

the back, and we could infer that our boys

were being enfiladed; and, further, so many

wounds were of such a trifling nature that it

was obvious that they were being tried too

severely for raw troops. So the night wore

on, and by next morning we were able to piece

together the whole awful story, which, so far

as I know, has never yet been published. Now

that it is all over, and the Fifth has wiped

out its failure so gloriously many a time

there is no reason for further secrecy.

After three hours of stupendous bombardment

our barrage lifted and the men went

over the top into feet of sticky mud. Five

minutes later a message came back that

there was no sign of an attack on our right,

and similar messages kept coming back, more

and more agonised. What had happened was,

that by some awful feat of blundering the

51st had not cut their own wire, and had

made no sally-ports to let their men out.

As these fresh young English lads jumped out

of their trenches they could do nothing but

run up and down the line like rabbits seeking

a way through; some of them tried to cut the

wire, and faced a frightful blast of shell and

machine gun fire, until human nature could

stand no more and they dropped back into

shelter. Then, as our men toiled onwards

through the mud, a great clattering on their

right announced that the Sugar-loaf was awake

and pouring a continuous stream of bullets

straight along our lines. So came to light

the second awful blunder. The heavy artillery,

which properly directed should, one

would have thought, have levelled mountains

had actually never landed a single shell on

that dreadful spot. And our right wing was

in the air.

Even then the day need not have been absolutely

lost if we had brought up every reserve

within reach, hurled them into the gap

between the two divisions, and shut out the

Sugar-loaf. The men themselves must have

felt this in their agony, for they made a

desperate attempt to dig a trench opposite the

Sugar-loaf, which would have blocked the

gap, but our force, was there too small,

and it was impossible to hold on in the teeth

of the storm of fire. But no reserves came,

and a third most horrible tragedy was in

store. Somebody again blundered, and a

misunderstanding arose as to the objective.

The idea spread abroad that the men were to

capture the first two lines of trenches, whereas

the true objective was the first line, and

small support line just behind. The bombers

and bayoneters dashed on through the

German fire and plunged over the German

first-line parapet, which had been practically

levelled by our bombardment;

their wire had been nearly all cut

by our field guns, and very few Germans were

found alive. Thence our men pushed on and

came to a battered and flattened-out little

trench, hardly more than a tattered and ragged

string of mud-holes. They did not recognise

this in the darkness as the as the limit of their

objective, but thought they must push on to

the second line proper, which was a long way

ahead. And then, most horrible of all, they

ran into our barrage. The torrent of shells

which had been protecting them suddenly

turned into an engine of destruction against

them. Signals had been arranged between the

infantry and the artillery, but here, too, something

went wrong, and information only

reached the artillery after some of our men

had actually performed the feat of going right

through our barrage, and were well on their

way to Fromelles. I believe that every man

who did this was either killed or captured;

and in the morning photographs showed a line

of our dead along the line of our barrage and

beyond. It must distinctly be understood that

our artillery was not to blame. The fault was

in the impetuosity of the untrained infantry,

who rushed on beyond their true objective

and in the horrible misunderstanding as to

what that objective was. In the midst of all

this orgy of blunders and of calamity, with

the sugar-loaf pouring a storm of shot and

shell along the lines, and the German artillery

counter-attacking in hottest blast, swarms of

infantry still bravely dashed over the top, only

to meet other swarms of disheartened men

dribbling back sick at heart, despairing, and

only anxious to reach safety.

I simply state the facts as I collected them

from a great number of sources, and believe

them to be true. There can be no doubt that

the effects upon the moral of the Fifth Division

were bad, and that that gallant force did

not recover for a considerable time. The

remnants were soon moved away from the line

and their place taken by the A. and S. Highlanders,

whereupon we all felt much relieved,

as the position had become exceedingly

serious, and had the Boche but known how

weak we were there was nothing to prevent

him from charging on to the Channel. The

casualties were said to be about 10,000 men,

of whom we heard rather authoritatively that

6850 were from the Fifth Division. Some battalions

lost nearly all their officers, and probably

the dead exceeded 2000. It must be remembered

that many of the casualties were

exceedingly slight.

To sum up, the infantry showed amazing

courage, but their lack of training was their

undoing. Had it been the Second Division

at that time, no doubt the results would have

been very different. The Australian Artillery

did splendidly. The staff work all

through could not be criticised, for it did not

exist. For our ten thousand casualties we

captured a few machine-guns and a hundred

prisoners, and it was rumoured that the Boche

had temporarily diverted 13 troop trains from

the Somme. His casualties appear to have

been trifling.

58

THE ARGUS, SATURDAY, APRIL 10, 1920.

FROMELLES, 1916!

A GLORIOUS FAILURE.

WHAT REALLY HAPPENED.

"The English attack in the region of Fromelles

was carried out, as we have ascertained,

by two strong divisions. The brave Bavarian

Division, against whose front the attack was

made, counted on the ground in front of them

more than 2,000 enemy corpses. We have

brought in so far 481 prisoners, including 10

officers, together with 16 machine-guns"—German

communique, July 21, 1916.

"Yesterday evening, south of Armentieres,

we carried out some important raids on a front

of two miles, in which Australian troops took

part. About 140 German prisoners were captured."

—British communique, July 20, 1916.

In this form readers of "The Argus" received

their first information of the great

action by Australian troops on the Western

front, which has since come to be known as

"the attack at Armentieres," or "the fight

at Fleurbaix," but was really "the battle

of Fromelles." For a long time the secrecy

of war kept a veil drawn over the details

of this sad page in the history of the Australian

Imperial Force, but closely censored

letters from members of the 8th, 14th, and

15th Infantry Brigades soon began to indicate

that something more serious had happened

than was at first suggested. Since

then more or less accurate accounts of the

battle have been in circulation, but the most

interesting features had necessarily to be

withheld until after the armistice. The

first consecutive record, prepared from official

documents and elaborated by commanding

officers who actually took part in the

engagement, has been prepared by Captain

A. D. Ellis. M.C, of the 29th Battalion,

and it is included in his "Story of the Fifth

Division" (London: Hodder and Stoughton).

In this the movements of the various units

from the day the intention to attack at Fromelles

was first announced until the work

of clearing up the battlefield had been

completed are carefully followed with the

aid of diagrams, and even the most unmilitary

reader will find much to stir him in

this account of "our most glorious failure."

QUICK INTO SERVICE.

On July 13, 1916 (less than a month after

its arrival in France), the 5th Australian

Division (under Major-General Sir James

McCay) was informed that it would participate

in operations intended to prevent

the enemy moving troops to the

Somme front. Orders were given that the

artillery preparation was to commence next

day, but it was not until July 16 that all

the batteries could be got into position,

although it had been arranged for the

attacks to be delivered on the 17th. The

objectives were the enemy front and support

lines on a front of about 4,000 yards,

which were to be taken and held. As soon

as definite information was available, all

ranks threw their energies into the work

of making ready. One task was the concentration

of over 60,000 rounds of 18-pounder

shell for the artillery, and proportionately

heavy stores of ammunition,

bombs, stores, &c., for the other units. All

of this had to be "man handled" through

crowded saps over the final stages of the

journey to the front lines. The 4th Australian

Divisional Artillery, as well as three

18-pounder batteries of the 121st (Imperial)

Artillery Brigade, were added to the artillery

of the 5th Division for the operations

(making 132 field guns). Judged by

later standards (205 "heavies" alone, ranging

from 6in. to 15in. howitzers, were used

at Polygon Wood), this was a comparatively

weak artillery support for an attacking division,

but it involved a great amount of preliminary

work. When in position the

guns had to make their registrations on new

targets and barrage lines all within two

days—during which mists prevailed—and in

such a way that the enemy would not suspect

that routine was being departed from.

Mists and fog were not, however, all to the

Australians' disadvantage, for at the appointed

time on July 17 preparations were

not complete, and to the relief of the exhausted

workers it was decided to postpone

the attack for two days, in the hope that

visibility would improve.

SEVEN HOURS' BOMBARDMENT.

The artillery programme was not complicated.

It comprised registration and a

certain amount of wire-cutting on the days

before the attack. At zero hour on

the 19th, an artillery bombardment of

seven hours' duration was to precede

the infantry attack. It was

considered that this would be sufficient

to flatten the enemy front and support lines

to such an extent that they would offer no

serious obstacle to the infantry. At stated

times throughout the seven hours' bombardment

a succession of four brief lifts to barrage

lines was arranged. These lifts were

to be of a few minutes' duration, and were

designed to induce the enemy to believe that

the infantry assault was about to commence,

and thus to cause him to come out of his underground

shelters and man his parapets.

At the conclusion of each lift the barrage

was to fall suddenly again on to the enemy

front line, where it was hoped it would

cause heavy casualties to his exposed infantry

and machine-gunners. For this reason

shrapnel was to be used for the first

two minutes after each lift, instead of high

explosive. During each lift the men in the

front line were instructed to show their

naked bayonets and dummy figures over the

parapet, in order to encourage the delusion

that they were about to assault. At 6 p.m.

the artillery was to lift finally to certain

barrage areas behind the objectives, where

it was hoped that it would afford the infantry

security during its consolidation of

the new positions. The medium and heavy

trench mortar programme was arranged on

similar lines, except that their special mission

was the destruction of the enemy wire

that skirted in thick, impenetrable waves

the entire enemy front line. The arrangements

for the infantry assault were somewhat

simple. The three brigades were to

attack each on a two-battalion frontage:

the third battalion was to be employed in

carrying stores to the attacking troops and

in garrisoning the front line after the others

had moved out of it. The fourth battalion

of each brigade was to be held in reserve.

The assaulting troops were to go over in

four waves at distances of about 100 yards.

The orders provided for the commencement

of the deployment of the leading wave in

No Man's Land 15 minutes before the final

lift of the artillery, and as near to the

enemy front as our own barrage permitted.

GERMANS ALERT

The morning of the 19th was calm and

misty, with the promise of a clear, find day

later. Reports from patrols in No Man's

Land during the night indicated that the

damage done to the enemy's wire was as yet

inconsiderable, but no great importance was

attached to that, as the chief part of the

artillery preparation had still to come. The

patrol reports disclosed also that the enemy

was very vigilant, and that close inspection

of parts of his wire was impossible owing

to the presence of strong enemy posts in No

Man's Land. At a quarter past 2 p.m., however,

there was a marked increase in enemy

counter preparation, and by 3 p.m. a heavy

and continuous volume of fire was falling

over the front and support line and the saps

leading to them, now filled with the

assembling infantry. The assembly was reported

complete on the 8th Brigade front

at 26 minutes past 3 p.m., on the 14th at

a quarter to 4 p.m., and on the 15th at 4

p.m. The men had received specially good

breakfasts and dinners, and were in high

spirits. The enemy fire continued to increase

in volume on the front trenches,

where already three of the four company

commanders of the 53rd Battalion had become

casualties.

Punctually at 5.45 p.m. deployment into

No Man's Land commenced, and it was

hoped that the artillery barrage would be

sufficiently intense to keep enemy heads

down until the deployment was completed.

On the extreme right of the 5th Divisional

frontage the 59th Battalion was scarcely

over the parapet before a little desultory

musketry fire was opened on it, coming

chiefly from the Sugar Loaf. Before the

men had gone 30 yards this fire had grown

in intensity, and a machine gun added its

significant voice to the rapidly increasing

fusillade. The waves pressed forward

steadily, but just as steadily the enemy fire

grew hotter, and the enemy front lines

were seen to be thickly manned with troops.

The losses mounted rapidly as the men

pressed gallantly on into the withering fire.

Lieut.-Colonel Harris was disabled by a

shell, and Major Layh took charge of the

dwindling line, which, finding a slight depression

about 100 yards from the enemy

parapet, halted in the scanty cover it provided.

and commenced to reorganise their

broken and depleted units.

THE THINNING LINES.

The deployment of the 60th Battalion was

attended by similar circumstances. Heavy

fire was encountered almost from the moment

of its appearance over the parapet.

Into this the troops pressed with the same

steadiness as that displayed by the 59th,

and with the same result. The ranks, especially

on the right, where they were most

exposed to the Sugar Loaf, thinned rapidly;

but the later waves followed on without

hesitation or confusion. On the left flank

more headway was made. To halt in No

Man's Land in these circumstances was to

court certain death, and Major McRae led

his troops towards the enemy parapet. It

was his last act of gallant leadership. Just

at the enemy wire the enfilade fire from the

Sugar Loaf became intense, and there almost

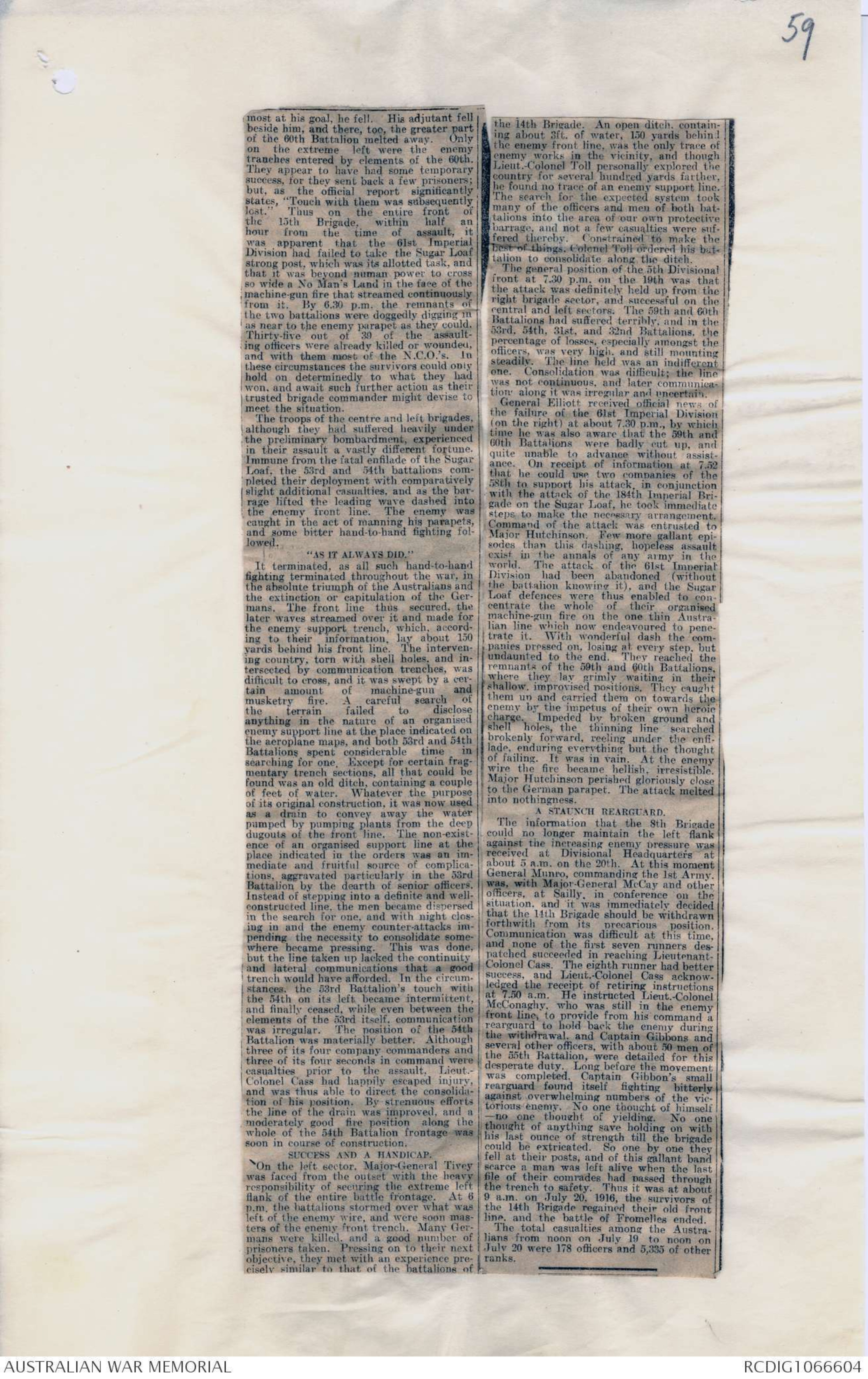

59

at his goal, he fell. His adjutant fell

beside him, and there, too, the greater part

of the 60th Battalion melted away. Only

on the extreme left were the enemy

tranches entered by elements of the 60th.

They appear to have had some temporary

success, for they sent back a few prisoners;

but, as the official report significantly

states, "Touch with them was subsequently

lost." Thus on the entire front of

the 15th Brigade, within half an

hour from the time of assault, it

was apparent that the 61st Imperial

Division had failed to take the Sugar Loaf

strong post, which was its allotted task, and

that it was beyond human power to cross

so wide a No Man's Land in the face of the

machine gun-fire that streamed continuously

from it. By 6.30 pm. the remnants of

the two battalions were doggedly digging in

as near to the enemy parapet as they could.

Thirty-five out of 39 of the assaulting

officers were already killed or wounded,

and with them most of the N.C.Os. In

these circumstances the survivors could only

hold on determinedly to what they had

won, and await such further action as their

trusted brigade commander might devise to

meet the situation.

The troops of the centre and left brigades,

although they had suffered heavily under

the preliminary bombardment, experienced

in their assault a vastly different fortune.

Immune from the fatal enfilade of the Sugar

Loaf, the 53rd and 54th battalions completed

their deployment with comparatively

slight additional casualties, and as the barrage

lifted the leading wave dashed into

the enemy front line. The enemy was

caught in the act of manning his parapets,

and some bitter hand-to hand fighting followed.

"AS IT ALWAYS DID."

It terminated, as all such hand-to-hand

fighting terminated throughout the war, in

the absolute triumph of the Australians and

the extinction or capitulation of the Germans.

The front line thus secured, the

later waves streamed over it and made for

the enemy support trench, which, according

to their information, lay about 150

yards behind his front line. The intervening

country, torn with shell holes, and intersected

by communication trenches, was

difficult to cross, and it was swept by a certain

amount of machine-gun and

musketry fire. A careful search of

the terrain failed to disclose

anything in the nature of an organised

enemy support line at the place indicated on

the aeroplane maps, and both the 53rd and 54th

Battalions spent considerable time in

searching for one. Except for certain fragmentary

trench sections, all that could be

found was an old ditch, containing a couple

of feet of water. Whatever the purpose

of its original construction, it was now used

as a drain to convey away the water

pumped by pumping plants from the deep

dugouts of the front line. The non-existence

of an organised support line at the

place indicated in the orders was an immediate

and fruitful source of complications,

aggravated particularly in the 53rd

Battalion by the dearth of senior officers.

Instead of stepping into a definite and well-constructed

line, the men became dispersed

in the search for one, and with night closing

in and the enemy counter-attacks impending

the necessity to consolidate somewhere

became pressing. This was done,

but the line taken up lacked the continuity

and lateral communications that a good

trench would have afforded. In the circumstances,

the 53rd Battalion's touch with

the 54th on its left became intermittent,

and finally ceased, while even between the

elements of the 53rd itself, communication

was irregular. The position of the 54th

Battalion was materially better. Although

three of its four company commanders and

three of its four seconds in command were

casualties prior to the assault, Lieut-Colonel

Cass had happily escaped injury,

and was thus able to direct the consolidation

of his position. By strenuous efforts

the line of the drain was improved, and a

moderately good fire position along the

whole of the 54th Battalion frontage was

soon in course of construction.

SUCCESS AND A HANDICAP.

On the left sector, Major-General Tivey

was faced from the outset with the heavy

responsibility of securing the extreme left

flank of the entire battle frontage. At 6

p.m. the battalions stormed over what was

left of the enemy wire, and were soon masters

of the enemy front trench. Many Germans

were killed, and a good number of

prisoners taken. Pressing on to their next

objective, they met with an experience precisely

similar to that of the battalions of

the 14th Brigade. An open ditch. containing

about 3ft. of water, 130 yards behind

the enemy front line, was the only trace of

enemy works in the vicinity, and though

Lieut.-Colonel Toll personally explored the

country for several hundred yards farther,

he found no trace of an enemy support line.

The search for the expected system took

many of the officers and men of both battalions

into the area of our own protective

barrage, and not a few casualties were suffered

thereby. Constrained to make the

best of things, Colonel Toll ordered his battalion

to consolidate along the ditch.

The general position of the 5th Divisional

front at 7.30 p.m. on the 19th was that

the attack was definitely held up from the

right brigade sector, and successful on the

central and left sectors. The 59th and 60th

Battalions had suffered terribly, and in the

53rd, 54th, 31st, and 32nd Battalions, the

percentage of losses, especially amongst

officers, was very high, and still mounting

steadily. The line held was an indifferent

one. Consolidation was difficult; the line

was not continuous, and later communication

along it was irregular and uncertain.

General Elliott received official news of

the failure of the 61st Imperial Division

(on the right) at about 7.30 p.m., by which

time he was also aware that the 59th and

60th Battalions were badly cut up, and

quite unable to advance without assistance.

On receipt of information at 7.52

that he could use two companies of the

58th to support his attack, in conjunction

with the attack of the 184th Imperial Brigade

on the Sugar Loaf, he took immediate

steps to make the necessary arrangement.

Commands of the attack was entrusted to

Major Hutchinson. Few more gallant episodes

than this dashing, hopeless assault

exist in the annals of any army in the

world. The attack of the 61st Imperial

Division had been abandoned (without

the battalion knowing it), and the Sugar

Loaf defences were thus enabled to concentrate

the whole of their organised

machine-gun fire on the one thin Australian

line which now endeavoured to penetrate

it. With wonderful dash the companies

pressed on, losing at every step, but

undaunted to the end. They reached the

remnants of the 59th and 60th Battalions,

where they lay grimly waiting in their

shallow, improvised positions. They caught

them up and carried them on towards the

enemy by the impetus of their own heroic

charge. Impeded by broken ground and

shell holes, the thinning line searched

brokenly forward, reeling under the enfilade,

enduring everything but the thought

of failing. It was in vain. At the enemy

wire the fire became hellish, irresistible.

Major Hutchinson perished gloriously close

to the German parapet. The attack melted

into nothingness.

A STAUNCH REARGUARD.

The information that the 8th Brigade

could no longer maintain the left flank

against the increasing enemy pressure was

received at Divisional Headquarters at

about 5 a.m. on the 20th. At this moment

General Munro, commanding the 1st Army,

was, with Major-General McCay and other

officers, at Sailly, in conference on the

situation, and it was immediately decided

that the 14th Brigade should be withdrawn

forthwith from its precarious position.

Communication was difficult at this time

and none of the first seven runners despatched

succeeded in reaching Lieutenant-Colonel

Cass. The eight runner had better

success, and Lieut.-Colonel Cass acknowledged

the receipt of retiring instructions

at 7.50 a.m. He instructed Lieut.-Colonel

McConaghy, who was still in the enemy

front line, to provide from his command a

rearguard to hold back the enemy during

the withdrawal, and Captain Gibbons and

several other officers, with about 50 men of

the 55th Battalion, were detailed for this

desperate duty. Long before the movement

was completed. Captain Gibbon's small

rearguard found itself fighting bitterly

against overwhelming numbers of the victorious

enemy. No one thought of himself

—no one thought of yielding. No one

thought of anything save holding on with

his last ounce of strength till the brigade

could be extricated. So one by one they

fell at their posts, and of this gallant band

scarce a man was left alive when the last

file of their comrades had passed through

the trench to safety. Thus it was at about

9 a.m. on July 20, 1916, the survivors of

the 14th Brigade regained their old front

line, and the battle of Fromelles ended.

The total casualties among the Australians

from noon on July 19 to noon on

July 20 were 178 officers and 5,335 of other

ranks.

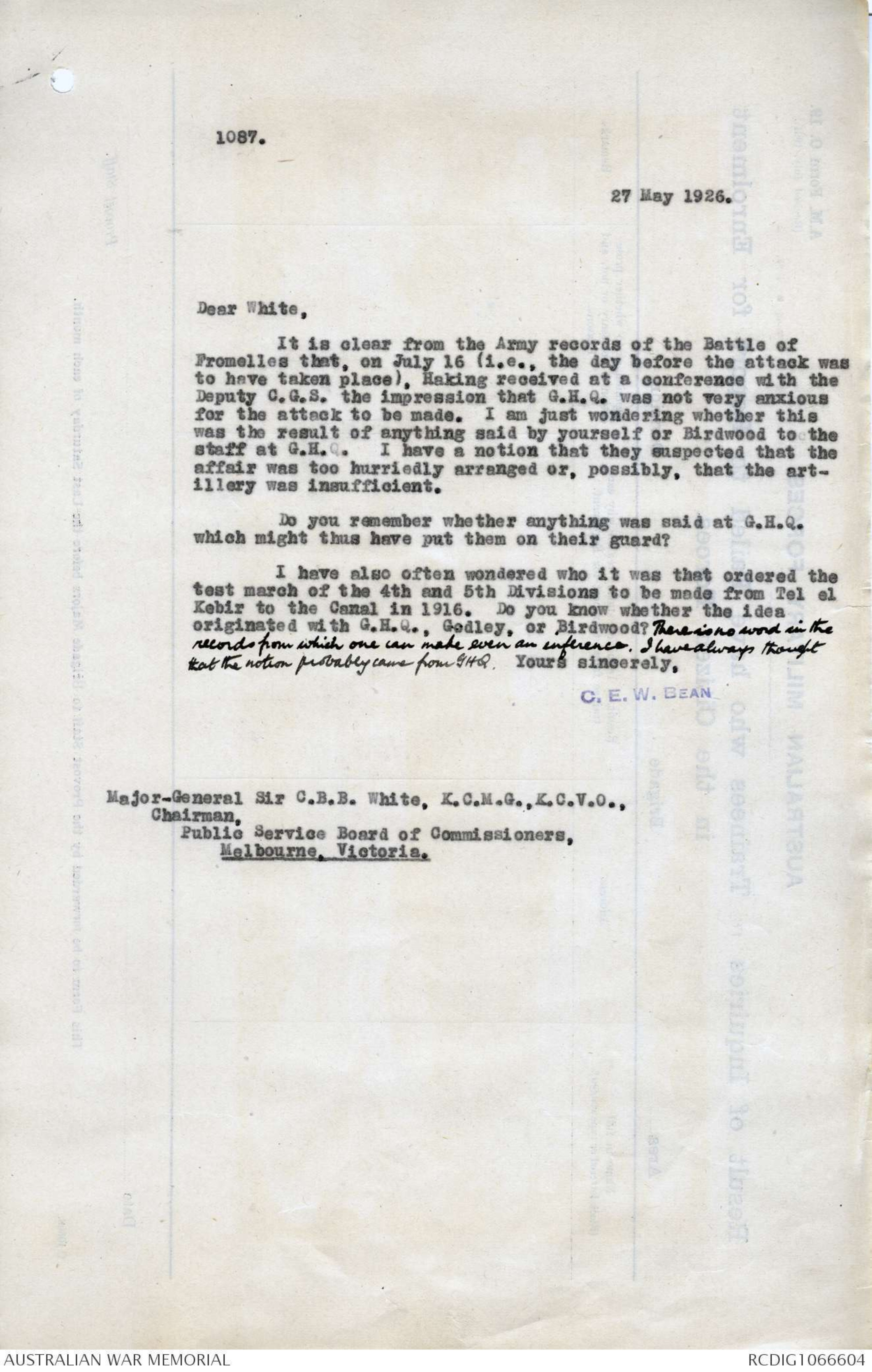

1087.

27 May 1926.

Dear White,

It is clear from the Army records of the Battle of

Fromelles that, on July 16 (i.e., the day before the attack was

to have taken place), Haking received at a conference with the

Deputy C.G.S. the impression that G.H.Q. was not very anxious

for the attack to be made. I am just wondering whether this

was the result of anything said by yourself or Birdwood to the

staff at G.H.Q. I have a notion that they suspected that the

affair was too hurriedly arranged or, possibly, that the artillery

was insufficient.

Do you remember whether anything was said at G.H.Q.

which might thus have put them on their guard?

I have also often wondered who it was that ordered the

test march of the 4th and 5th Divisions to be made from Tel el

Kebir to the Canal in 1916. Do you know whether the idea

originated with G.H.Q., Godley, or Birdwood? [*There is no word in the

records from which one can make even an inference. I have always thought

that the notion probably came from GHQ.*]

Yours sincerely,

C.E.W.BEAN

Major-General Sir C.B.B. White, K.C.M.G., K.C.V.O.,

Chairman,

Public Service Board of Commissioners,

Melbourne, Victoria.

[*HN*]

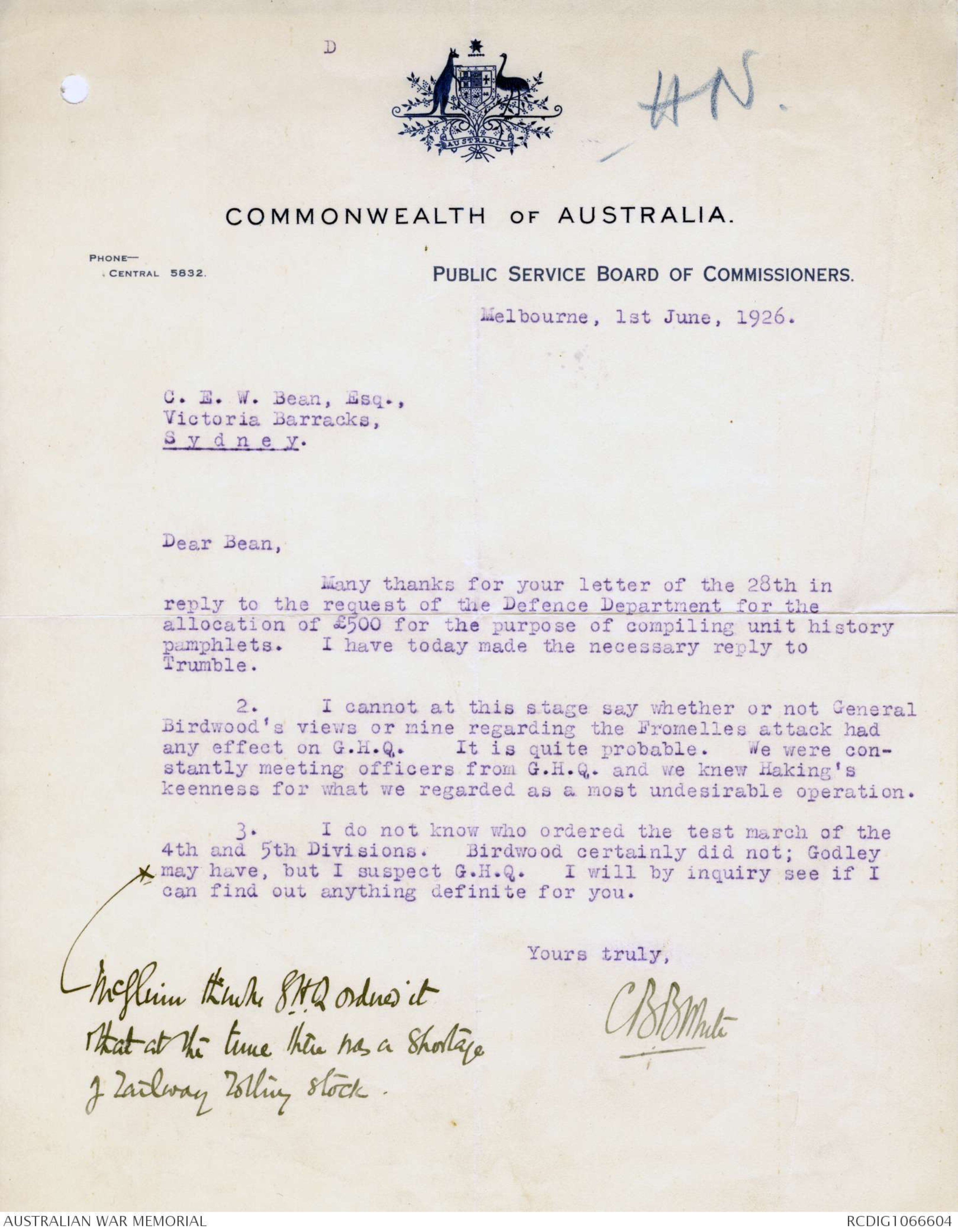

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA.

PHONE-

CENTRAL 5832

PUBLIC SERVICE BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS

Melbourne, 1st June, 1926.

C. E. W. Bean, Esq.,

Victoria Barracks,

Sydney.

Dear Bean,

Many thanks for your letter of the 28th in

reply to the request of the Defence Department for the

allocation of £500 for the purpose of compiling unit history

pamphlets. I have today made the necessary reply to

Trumble.

2. I cannot at this stage say whether or not General

Birdwood's views or mine regarding the Fromelles attack had

any effect on G.H.Q. It is quite probable. We were constantly

meeting officers from G.H.Q. and we knew Haking's

keenness for what we regarded as a most undesirable operation.

3. I do not know who ordered the test march of the

4th and 5th Divisions. Birdwood certainly did not; Godley

x may have, but I suspect G.H.Q. I will by inquiry see if I

can find out anything definite for you.

Yours truly,

CBB White

[*McGlinn thought G.H.Q. ordered it

& that at the time there was a shortage

of railway rolling stock.*]

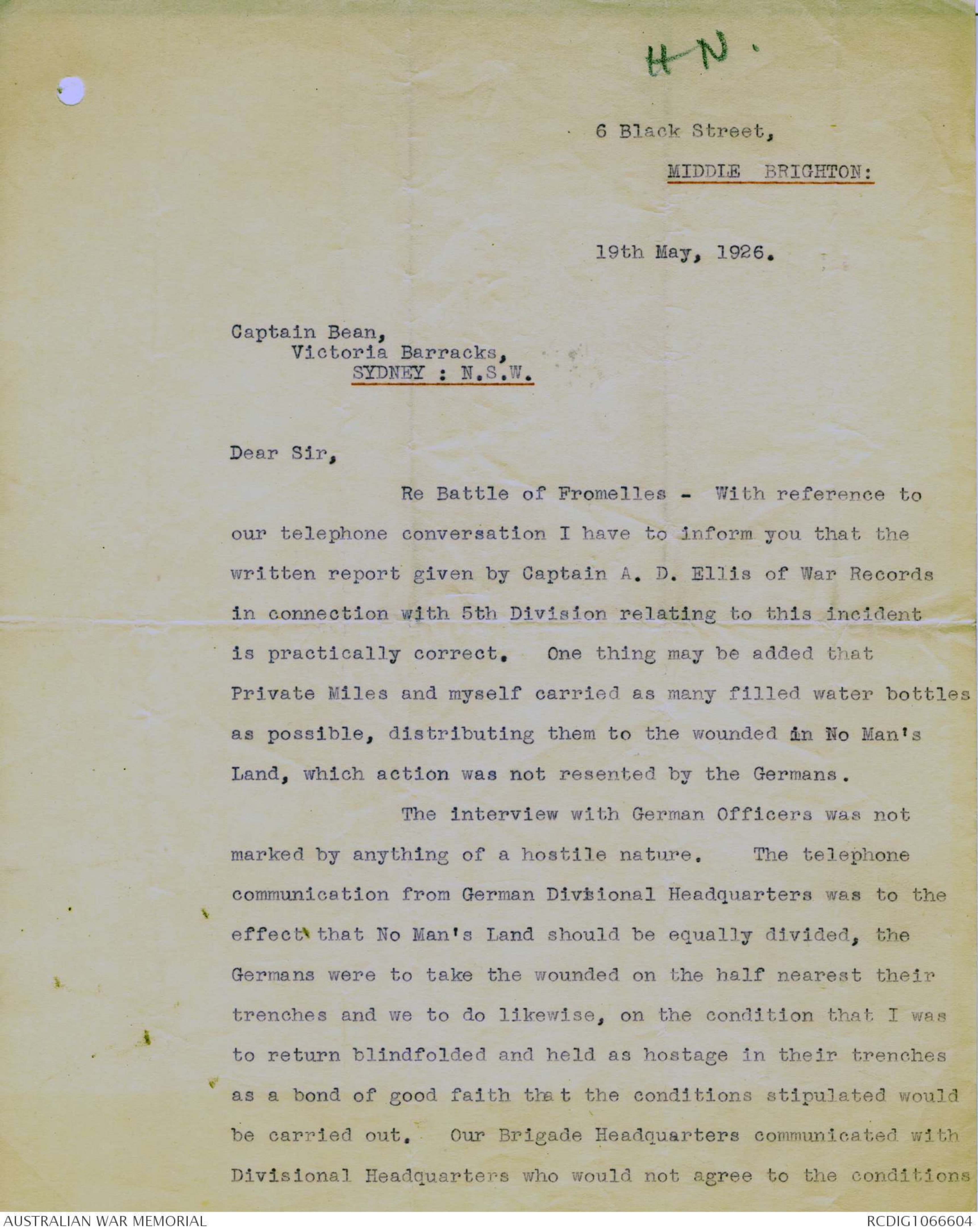

[*HN.*]

6 Black Street,

MIDDLE BRIGHTON:

19th May, 1926.

Captain Bean,

Victoria Barracks

SYDNEY : N.S.W.

Dear Sir,

Re Battle of Fromelles - With reference to

our telephone conversation I have to inform you that the

written report given by Captain A. D. Ellis of War Records

in connection with 5th Division relating to this incident

is practically correct. One thing may be added that

Private Miles and myself carried as many filled water bottles

as possible, distributing them to the wounded in No Man's

Land, which action was not resented by the Germans.

The interview with German Officers was not

marked by anything of a hostile nature. The telephone

communication from German Divisional Headquarters was to the

effect that No Man's Land should be equally divided, the

Germans were to take the wounded on the half nearest their

trenches and we to do likewise, on the condition that I was

to return blindfolded and held as hostage in their trenches

as a bond of good faith that the conditions stipulated would

be carried out. Our Brigade Headquarters communicated with

Divisional Headquarters who would not agree to the conditions

Deb Parkinson

Deb ParkinsonThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.