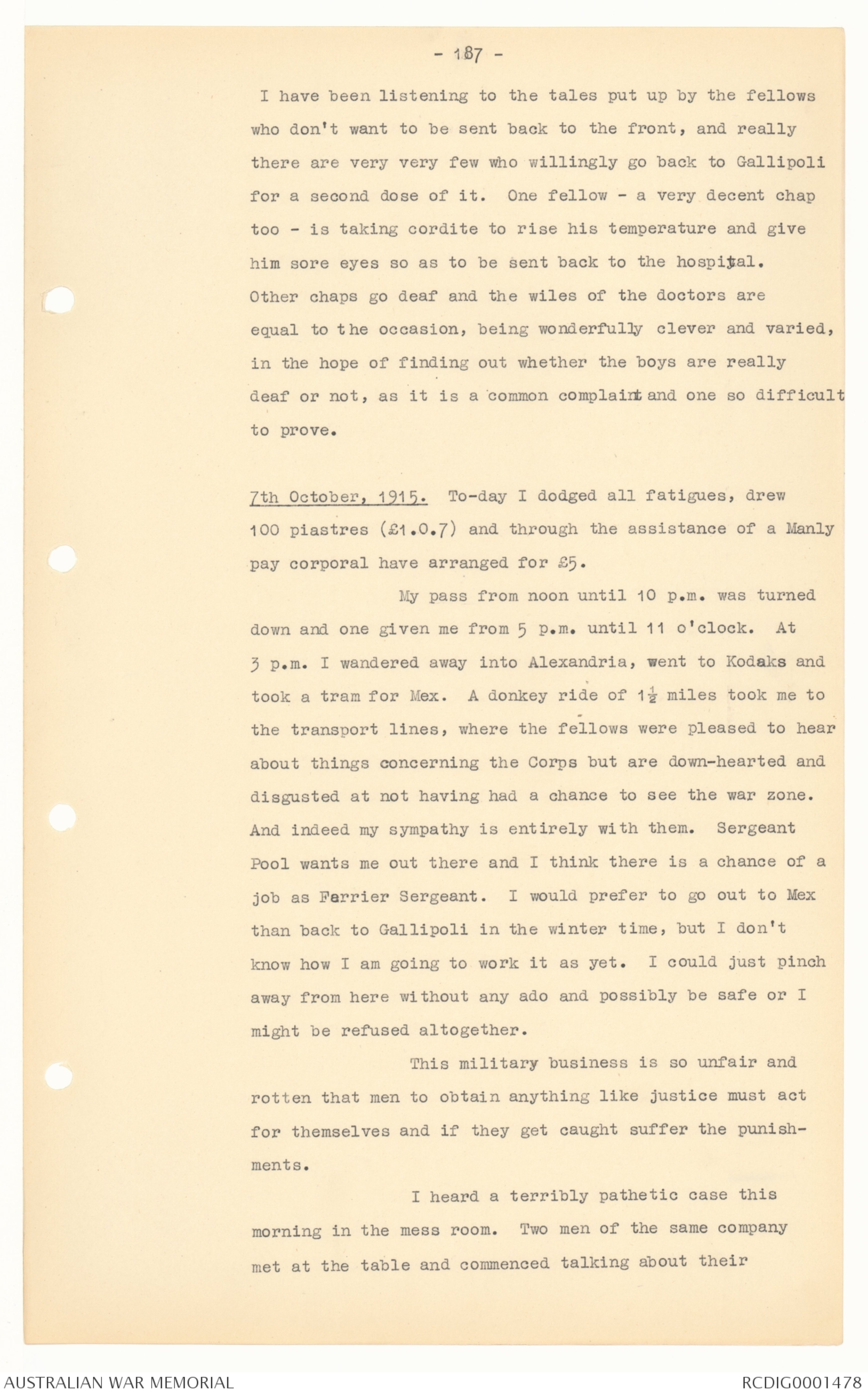

Thomas James Richards, Diaries, Transcript Vol. 2 - Part 19

- 178 -

It seemed strange to me/that the "Catacombs"

were so dry at a depth of 95 ft., more so as there is a

canal which connects Alexandria to the Nile River, only

100 yards away.

These wonderful Catacombs were discovered by

accident as recently, I believe, as 1912, at which time

they were full up with water and debris.

I intended leaving the Catacombs in the cab

garry that waited for me but fearing it would be rather

late I discharged the cabman and to his astonishment I

gave him 10 piastres (2/1). Cabs are very cheap here.

I had this man for 1½ hours - a 6/- job in Australia.

It was now 5.30 and getting dull. I went on

to the sea front where there were a number of people of all

colours sitting and walking about. A nice breeze was

blowing, and as I leaned on the sea wall I thought, as I

gazed upon the ruins of the old lighthouse built by the

Romans and handed down to us, until it collapsed as one

of the world's seven wonders - Phasos Light, 590 feet

high. It was never considered a safe structure though

it remained for the earthquake in 13th century to destroy

it.

On strolling back into the main thoroughfare

I passed through the Gardens (which were remarkably

pretty and covered with grass when I saw them months

before). The Summer and the natives running wildly over

it has made it bare now. Groups of coloured families were

picturesquely resting leisurely and contentedly while the

children kicked a rag soccer ball about and the youth

gathered in bands and played good-naturedly at a game in

which one has to guess the man that touches or hits the

person standing up-right with right hand bent upwards

against the side of his face, and other other, palm

outwards, folded under the right arm.

- 179-

The players stand aside and behind and when

one man hits the palm either a light or a heavy blow

(and some of them fairly rattled the prisoner) the whole

of the players crowd in and holding a hand, finger

extended, up for the leading artist to pick out the

person who struck the blow. If successful, they

change places and so the game goes on continuously and

with considerable merriment.

I went down to get some dinner but after the

first course the place did not suit me so I went and did

some shopping deciding to dine later at the "Serene" at

7.30. This I did, after buying a volume of Omar Khyyam

for the Night Sister, Miss A. M. Wood, who at present is

very disgusted with me on account of my freeness and her

own pitiful simplicity but as I promised, so I will fulfil.

At 7.40 I got into "Serenes" and remained at

a table by myself - a one-man table - enjoying a fine

dinner with decent china and silver, white tablecloth

and a real serviette, midst the charm of a bowl of flowers

at my right elbow. The service was frightfully slow,

so much so that when I enquired the time from some

Frenchmen, after devouring some five courses with sweets

and fruit still to follow, learnt to my surprise and

horror that it was 9 o'clock, and the last train leaves

at 9.5 p.m. I paid up my 15 piastres (3/1d.) and after

some delay a cab was found to run me down to the tramshed

where the fellows often told me it was possible to overtake

the train at Victoria Station, some five miles out.

After a very pleasant ride through pretty San Stefano I

landed at Victoria College only to find the train had

gone through ten minutes earlier. My pass was for 10

o'clock and the authorities were pretty strict, but alas!

it was 7 minutes to ten and I had six miles to do either

on foot or on a donkey. They donkey man wanted 2/-. I

offered 1/-. We eventually settled up at 1/3 and on

- 180 -

the donkey with a big Arab planting whacks to the donkey's

rudder every few feet and shouting every time.

The night was very dark but this improved the glory of the

stars, so I was in my element even though the nigger

running behind (essential as he was) did irritate me.

We left the railway track and went into a dark and mystic

palm grove for half a mile, the Arab shouting and hitting

the donkey a severe blow causing the animal to canter.

The Arab had to run behind to keep up, as he could not

run on the sand more than 70 yards at a time. The journey

therefore meant a series of short sprints the whole way

through. This may not have been so bad but for the fact

that the saddle was a cumbersome affair that rolled about

somewhat and di not give me a chance to feel my knee grip

against the ribs. It was all saddle. This was all right

after a while and I did not notice it, but having no

stirrup irons and a rough carpet covering over the saddle

my bare knees and the inside of my legs right up got a

very rough time and rubbed through in several places before

we reached the back fence, where I gave the nigger 1½

piastres and bade him "good night." During the latter stage

of the continuous journey the moon gave a glorious

exhibition of its majestic powers, rising out of the palm

trees throwing their handsome shadows towards me, and at

the same time tingeing the dampened sand (the dew or

humidity is heavy at night times these hot days) with a

surface of changing sheen in colours from crimson to old

gold, presenting to me a brilliant spectacle and one that

I was quite prepared to suffer punishment for from the

orderly room on the morrow for coming in after "lights

out." That few miles trip was something to remember,

being as I was far from habitation with only a donkey

and an Arab for mortal company. The magnitude and

grandeur of the Heavens combined with the novel position

and the probable prediction on the following day, kept

- 181 -

my mind in a state of calmness and peacefulness.

After dispensing with the services of the

donkey and his counter-part I had some half mile of narrow

road, hemmed in with trees, to wind along and follow. The

shade was very thick and dark but yet the light beams that

did penetrate and find their way through did, with the

damp, musty smell, give me rather an interesting and

fantastic display. On reaching my balcony ward where there

are some 63 beds, I met the Night Sister who is very

particular about the fellows being in punctually, happened

to be in the darkened ward and so I ran face to face with

her, puttees rolled up and boots in hand, as they make

a terrible clatter on the tiled floor. She asked for an

explanation and got for a reply "The damned trains in this

country forget when and where to run at times."

I slept as usual on the isolated reading and

music balcony and woke up with the flies at daylight, but I

spent a great day and one that was novel and full of the

unexpected.

1st October, 1915. To-day has passed by without anything

serious or otherwise happening.

I took my clothes back to the pack store at

10 a.m. Took and made a mess of some photographs for Sister

Bermister. Received a letter from Mrs. Ferguson and some

small books from Maggie in Wales.

After dinner I wrapped up two parcels and

then tied them together for S. J. Graves of the 7th Light

Horse to take back to Sydney for me and leave with A.

Hollingsworth. These are three diaries and a lot of written

matter in one parcel and a shell time fuse with Turkish

bullets and some souvenirs in the other. Graves left at

2 p.m. with a party of 26 men "invalided home" to Australia.

As yet I have heard nothing about coming in

late last night.

- 182 -

A Scotch piper band has been playing here for an

hour or so this evening and night. Nobody actually likes

them and still more strange is the fact that nobody disapproves

of them. The sound 'midst this isolation, however,

does the men a lot of good. It is relaxation at any rate.

2nd October, 1915. I arranged my discharge for Monday

with four days' light duty at Mustapha. I have been

dabbling with photo. prints all day long with only more

or less success./

I have written to Hollingsworth, Ferguson, Mother,

Ralph Hill and probably to Bert to-morrow.

I have a little story to tell one day of woman's

idea of fair play. It is too delicate to deal with now,

but it's wonderful where some women get their weird,

unfair tactics from.

My total credit at present is only 4/-. I expect

to draw on Tuesday next though. I must have some £6 due to

me at 1/6 a day now, even though I did draw £2.16.3 in

Cairo.

Poor Mrs. Cadell received a note simply stating

that her services would no longer be required from this

date, and ended by thanking for devotion to duty etc.

The English people have engineered this to get

rid of her as she is always up against them with her

Australian ideas and strong head, yet I think the loss of

her son is playing terribly upon her mind and bends her

heart towards all Australians almost to excess.

3rd October, 1915. I am cleaning up to-day so as to be

able to get away in comfort to-morrow and find an unfinished

article on the Australian gum trees and the lack

of appreciation these splendid trees receive from Australians

themselves, while in all countries which have

imported these trees they are loved both for their

- 183 -

commercial value and their value as shade and decorative

trees. They seem to grow well in all countries. I have

seen them doing beautifully in Europe (Nice). St. Helena,

California, Africa and Egypt. and feel surprised that

they are not more popular in Australia. All of our few

decent avenues should be lined with them both for shade

and appearance. I hope to do this article one day.

I have just returned from a decently long

swim and am sitting on the verandah watching some films

drying. While walking down to the water it dawned on me,

as it has done many many times, that I am stooping more

and more if anything, and I tried to argue out the cause,

if any. Was it laziness - lack of interest in my personal

appearance? This afternoon there are many soldier visitors

around and as I observed the brightness of their leggings,

boots, bandoliers, etc. and the proud, upright carriage

of these fellows who, by the way, have not yet been under

fire (having been in Alexandria the whole time), it made

me wonder why I was not proud of my uniform also and why

I did not walk upright and strut about with more gracefulness,

more particularly now that I have been well seasoned

to all kinds of man-killing devices and more and more

particularly seeing that I have been mentioned in despatches

by an officer of the 7th L.H. and an entire stranger to me.

But no, I am not a bit proud of my position. The fact that

I am an Ambulance man, a non-combatant, seems to weigh me

down and yet I have no longing for infantry work at any

cost. Aviation seems to me the only thing about war that

I could be satisfied with. I cannot be proud of the army

or anything pertaining to military business on account of

the robbery and lack of trust that the officers place in

their men, especially in this hospital. There seems to

be no such thing as honour and this hurts me very much.

- 184 -

4th October, 1915. I leave Montazah House. I slept on

the wide, open verandah last night as usual and about 4 a.m.

Sister Woods brought me a cup of tea and some biscuits as

was her custom some days ago but it lapsed owing to a little

clash we had one night. It was her want to wake me up at

4 a.m. and talk until 5.30 or so, and as she is the proper

English middle-class with superior notions that won’t bear

the light of practicability to-day, I set about disillusioning

her. Jolly, perhaps, but yet a fact, and

worse, perhaps, was the fact that my discussion mostly

centred on and around the prevailing social problems of

the day, and we drifted on and on until she saw fit to

disentangle herself and refuse my presentation of a volume

of Omar Khayyam, and instead of bring me tea and biscuits

she used to send the orderly with it. Miss A. M. Woods

was going to Cairo to-day, so last night she ventured to

bring the tea herself, which I took as a token of friendship

and followed it up by going into the dressing room

and engaging her in a reconcilatory conversation for

an hour and a half. I succeeded in pointing out where

her weakness lay and what it was that actually caused the

rupture between us. I left her on excellent terms which

was later verified by her coming to my couch and speaking

of the object lesson received and expressing sorrow at

our parting. Nothing would have hurt me more than to have

lost her confidence and friendship, and this I really

thought was going to happen. Therefore I worked hard

and with many giles to even matters, and so we parted the

best of friends which pleases me very very much, as I

grieve to leave a bad friend in my wake no matter who or

where.

I shook hands with most of the sisters

about the Home and left at 2 p.m. by train for Mustapha,

arriving there 45 minutes later. Our party consisted of

4 Englishmen and 4 Australians. Nobody met us at Sidi

Gabu station and we had a hell of a time looking for the

officers and finding our camp quarters, carrying our

- 185 -

barrage around the whole time.

We eventually got quartered up in a tent near

the seashore on the heavy sand. General leave was granted

from 5 to 9.30 p.m. I went up town, walked around a little,

did some shopping, films at E Del Mar, and dropped into a

huge drinking hall that provides a musical and picture programme

free but charge 4 piastres for a drink (10d.).

This can hardly be considered excessive when the class of

show provided is taken into consideration, some of the

dancing turns being excellent. I met Fred Arons in this

Palace and he is getting on splendidly. I must call at

his Artillery transport camp and see him. I got home and

slept well in the sand, although the beds and sheets that

I have become used to of late weeks were sadly missed, and

now I find myself surrounded by the rigours of active

service. I don’t very much care what they do with me,

though the plain truth has been slowly dawning upon me

during the last two days that it is rank folly to hanker

after another turn at Gallipoli. A man doesn't get a dog's

chance there and after all a few men or a few hundred is

neither here nor there, and if I remain here with the

transport section I will be relieving a man for the front

just as good as myself.

Lady Graham was at the Hospital and made

a point of seeing me and conversing for half an hour.

I gave her three films from which to have enlargements

taken and she promises to have them sent on to Australia

to Hollingsworth address.

5th October, 1915. I went up town to-night after an easy

day during which I presented a claim for £5 and had a

decent swim and found some of my old friends accidentally.

The heat seems terrible here on the sand, and as I am

wearing heavy military clothes I feel it rather badly

and would not care if I had stayed on at Montazah for a

- 186 -

while longer. The food here is up to putty too and I

was never so absolutely short of cash. Last night I

walked in from Alexandria and spent my last ½ piastre

on a pomegranate which I ate before getting back to camp,

penniless. I have never been absolutely broke in my life

until coming to Egypt and the present is probably the

worst on account of the possibility of my removal to

Lemnos any moment now and the number of purchases I

have to make for the boys at the front.

6th October, 1915. Up at 5. Parade at 6 a.m., which

is just a roll call and the arrangement of fatigue parties.

I was pulled out for guard duties but as only four out of

the six were wanted I got away and instead of going on to

the ordinary parade I bolted off and walked into

Alexandria, looking all along the road (2½ miles) for

photographs but I only made one exposure. At the Ramleh

terminus I met Mrs. Cadell and promised to call upon her

at Sterling House, Capt. Finley, at 6 p.m., but at 6 p.m.

I walked and walked for miles and miles trying to fathom

the directions given me by Mrs. Cadell, giving up the

ghost at 8 p.m. and coming back to camp, rather annoyed

as I wanted to see Stirling House, as I understand there

are some nice people there.

To-day was pay-day but I was amongst the

party who did not get a chance to draw until the office

was shut down and a promise to pay to-morrow was forthcoming.

It is surprising in what a short space of

time a fellow can grip the illegal means of getting out

of camp. General leave is given at 5 p.m. until 9.30

but I went out in the morning saying to the guard with

a stern look of indignation when he held me up - "Base

post office duties" and passed right on.

The tricks that the fellows get on to here

are wonderfully cunning and surprisingly well executed

- 187 -

I have been listening to the tales put up by the fellows

who don't want to be sent back to the front, and really

there are very very few who willingly go back to Gallipoli

for a second dose of it. One fellow - a very decent chap

too - is taking cordite to rise his temperature and give

him sore eyes so as to be sent back to the hospital.

Other chaps go deaf and the wiles of the doctors are

equal to the occasion, being wonderfully clever and varied,

in the hope of finding out whether the boys are really

deaf or not, as it is a common complaint and one so difficult

to prove.

7th October, 1915. To-day I dodged all fatigues, drew

100 piastres (£1.0.7) and through the assistance of a Manly

pay corporal have arranged for £5.

My pass from noon until 10 p.m. was turned

down and one given me from 5 p.m. until 11 o'clock. At

3 p.m. I wandered away into Alexandria, went to Kodaks and

took a tram for Mex. A donkey ride of 1½ miles took me to

the transport lines, where the fellows were pleased to hear

about things concerning the Corps but are down-hearted and

disgusted at not having had a chance to see the war zone.

And indeed my sympathy is entirely with them. Sergeant

Pool wants me out there and I think there is a chance of a

job as Farrier Sergeant. I would prefer to go out to Mex

than back to Gallipoli in the winter time, but I don’t

know how I am going to work it as yet. I could just pinch

away from here without any ado and possibly be safe or I

might be refused altogether.

This military business is so unfair and

rotten that men to obtain anything like justice must act

for themselves and if they get caught suffer the punishments.

I heard a terribly pathetic case this

morning in the mess room. Two men of the same company

met at the table and commenced talking about their

Not Yet Replaced By AI

Not Yet Replaced By AIThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.