Memoir of John Shakespear Bartley, 1916-1919 - Part 10

Period 3.

-11-

felt they needed it. No. 2880 to sit down on the road,

sometimes in a pool of water, and barely had the strength to rise

up again; for the pack seemed to pin him to the ground, and those

shoulders did ache. Both No. 2880 and No. 2929 went right through

with the march. At one stage some-one fired a shot which whistled

past the Colonel, who was trying to urge the men on. About

four in the morning the billets were reached, at least the billeting

area, and when all the "stragglers" came along, it happened

that Sergt. BUTTERWORTH afterwards killed in action; lost them in

an attempt to locate the billets and more men fell out. Finally

the men were quartered in the usual barn and slept like new-born

babes. Those who fell out reported back next day, and a waggon

was sent back over the route to collect what gear had been dumped.

The village bore the name of Bussus(?) Thus the Long-pres-

Bussus march was a famous one, and was the worst march during

No. 2880 and No. 2929's term with the Battalion.

The "froggies" (French people) at Bussus were afraid of the

"wild Australian Soldats", for the shop-keepers only allowed a

few men in at a time to be served and would then close the door.

All the people locked up their houses and kept a close watch on

them. They had never seen Australians before, and perhaps they

may have heard strange tales about them. But it must be written

about there as elsewhere, if the Aussie was not welcome, his

money was.

Large apple orchards were in the district, but for some reason

the trees had been neglected for a long time and had been

unpruned for years, and the old adage that stolen fruits are

sweetest, proved wrong in that village.

On 21st October the Battalion moved on towards the Somme

front and motor transports took them to a place named Beurie(?)

A couple of nights were spent in this village. It was awfully

cold and they billeted on the cold cement floor of a room containing

a draughty fire place (of course there was no fire) and

having the glass panes removed from the windows. As usual it

was dark when they arrived, but upon "poking about"

Period 3.

-12-

the place, a barn full of straw was discovered, having a ladder

leading up to the top. Here was temptation, but a freezing floor

knows no conscience, and very soon they emerged with the "goods"

and laid down a good bed of "straw", but the orderly officer

ordered the stuff to go back to the barn again, as it was unthrashed

wheat. So No. 2880 emerged into the cold night and was

about to enter one barn door, just as a Frenchman (leading a couple

of horses) happened to be coming out another. War was declared

on sight, and No. 2880 dropped the "straw" and thinking that

discretion was the better part of valour, fled into the night with

the Frenchman in full pursuit and armed with a pitch-fork, and

calling out at intervals "Le Capitaine! Le Capitaine!" But he

was very soon lost in the darkness.

Next morning they could get no water. A large cask was standing

in the yard containing water, and the troops freely helped

themselves until disturbed by the same Frenchman, who refused

to allow the men water to wash with. During the stay there, that

same "froggie" made it quiet a habit of inspecting his tumble-down

out-places, so that he might get a chance to put a bill in for

damages. Some of them were master-hands at that, too.

Such, was a typical treatment that the lads received in that

part of France (The Somme) in 1916. Surely they must have been

hun sympathisers? Other parts of France were so very, very different

as regards the treatment of our men.

On 27th October, the Battalion marched to "Hungry Hill",

so named on account of the small issue of rations. On this hill

a tarpaulin was rigged up for shelter and 40 men (one platoon)

were placed under this, lying on their sides, and remaining like

that all night. If they wanted to turn, then all had to turn

together. Any how it was better than being out in the frost all

night.

On one occasion, Lieut. Dad White told Pte. Donniger and No.

2880 and No 2929 and a few others, who could not crawl under the

tarpaulin (on account of there being no further room, as the last

man was about half in and half out in the frost) to go over and

sleep in an ammunition shed, and to allow no one to turn them out.

Period 3.

-13-

So thinking that they "were in clover" the boys went over and cooked

a meal, consisting of fried-bully, in a dixie lid. A fire was

lighted close to a dump of .303 cartridges. Presently there came

along, swelling with importance a certain Sergeant-Major of the

29th Battalion, with whom the boys had previously struck trouble

at Armentieres. He gave them notice to get out as the shed was

situated in the 29th Battalion Area. The lads refused and the

R.S.M. significantly drew attention to his revolver. Donniger

came to the front, by informing him that "we all had rifles and

bayonets." So he departed, but only to return again, this time

accompanied with a Major. This gentleman told the R.S.M. to give

them time to get out, and if they didn't go, to put them out by

force. So after a conference with their own officers ("Dad" and

Lieut. Coleman) the boys had to vacate, and had to crawl back under

the tarpaulin, somehow.

Hungry Hill was not far from Flers, and well under shell fire

and a good place to be out of, and many a freeze the men did of

a night, when placed and packed in those dug-outs of the "get-out

now and again for a rest type".

No. 2880 well recollects the duck-board fatigue (the Duck-Board

Barriers)from the Hungry Hill to Needle Dump, along the

duckboards, the night he and Donniger and others got lost coming

back. No one seemed to care for that kind of fatigue for it was

no "cop". The boards were often dumped by men, who were too

exhausted to carry them, and by others who deliberately threw them

away.

Duckboards were laid for miles behind the trenches, and it was

only natural that artillery and machine gun fire would be directed

on them, and Fritz made an awful mess of the track at times. The

boards were necessary on account of the marshy ground.

On 23rd October, the Company moved from Hungry Hill to the

support line at Flers. As usual the men were heavily laden,

and No. 2880 fell back a little, owing to carrying a bucket of

Will's Bombs, till relieved of the load, when he came up again

with the "mob".

Before . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Period 3.

-14-

ering Fish Alley, it became noticeable that dead Tommies were

ing about; it was an uncommon sight to them.

Working their way up Fish Alley, and past Flers dump, they

took over from the Tommies. Fish Alley was nothing more or less

than a creek, and mud was abundant, and the troops had no gum-boots waders). A little on the right was the Village of Flers (in No-

Man's-Land), with its grave-yard of tanks and dead mules ("donks").

and its cellars containing German dead. Fritz was constantly shelling

the village and support line, and it was a lively place to be

in. For ten days and nights the Company occupied this trench, under

Cap. Cheeseman and "Dad" White, and truly they lived an amphibious

life.

In a letter, written home on November 3, 1916, No. 2880, said

(passed by Censor) "I am having all manner of experiences. To

relate all would be impossible. I have been in trenches where we

had to walk through mud and water well over our knees, have slept

out in the rain, owing to dug-outs falling in, and been out in the

open country on Fatigues of a night amongst the shells. Trying to

dodge bursting shells is not a pleasant occupation. The huns tried

to poison us with gas shells. I saw dozens of German dead, all

around us. Those big guns of ours play havoc with Fritz. Shells

are screeching over like peas. Our Artillery is magnificent. We

are in the midst of it all now, and so far I am not hurt, though

I have had several near goes with flying splinters. The air is

like an ant-bed at times with our planes. I have seen those

wonderful tanks, that you have been reading about. Woods and

Villages around here are levelled to the ground.

During the ten days in, a stunt (attack) on a large scale,

was to have taken place, with its final objective Bapaume, a tower

of which could be seen from the trench. "We'll enter Bapaume, yet"

remarked Cap. Cheeseman., one day; later on, he did and won the French Legion of Honour." But owing to the wet weather and the mud the attack, after waiting night after night was postponed. To attempt

to walk across No-Man's Land, was a sure certainty of bogging up

to the waist. So the time was spent in the line and fatigue work.

Period 3. Page 15.

Donniger and Dad Easlie (killed in Action, later on) and others

used to go across to the village and bring back good water, vegetables,

and coal. The huns had left the vegetables planted.

So Donniger's "famous stews" were made on the premises.

They were boiled mostly in yellow shell-hole water, as the village

was only accessable during foggy weather, and even then it

was shelled.

Being in support lines, it was possible to have a fire.

Braziers were made and the coal from the village became good fuel.

This coal was a compound and was the same shape and a little

larger than an egg.

One night someone dropped a live cartridge into the Sergeant's

Brazier, and poor old No. 2929 received the credit for

doing it from Curnow, though he never did so.

Those who remember Dad Easlie, will always remember his

"Black-fellow" fires, and the manner in which he used to crouch

over them, having his pipe constantly in his mouth and carrying on

in his dry old manner. One day, Dad reported sick, and later, the

doctor found him crouching over a smoky coal fire, apparently

(not intentionally, though) inhaling the fumes, and "roared" Dad

up.

No. 2880 ventured on a couple of visits to the village, but

the shells soon kept him in the sap. Going over to Flers was

"no bon". A Tommy was killed over at the village pump one morning.

A little while before he was boasting "no hun shell had

his number on". He had been through Gallipoli.

During the stay in the support lines, many trips were

made to Flers Dump, which usually came in well for its share of

shells, and Lieut. - ---, and two men were killed.

A fatigue was sent out one day to lay a cable in broad-

daylight. A six-foot trench had to be dug to lay the cable

down in, and the place was not far from Fritz, and at the foot

of the hill.

But the huns turned artillery on the fatigue party, and

a retreat was ordered. One shell, luckily a dud, passed right

through one man's legs. "Minniwerfer Bill" was in charge of

Period 3.

-16-

the party.

Trench feet now began to make their appearance, and the

"chats" became abundant.

The big "howitzers" behind the line, were wheel to wheel.

There were many guns covering the front and one French 75 could

be distinguished from all the rest, barking away all night, behind

the position of No.2880 and No. 2929. The short sharp bark

of a French 75, cannot be forgotten, nor can the hun 77, or

Whizz-bang.

A host of sap fatigues were done, as the Trench began to

fall in, owing to the nature of the earth, and the rainy weather.

Thus began the long winter campaign of 1916-17, on the Somme.

The mud was awful; the men shortened their great coats, by cutting

off a width from the bottom with their bayonets, as the weight

of the clinging wet mud was too cumbersome to carry about. (Prior

to leaving Liverpool, Australia, the men's coats were all measured

with a stick by Major Chaseling who made all men embark with very

long coats. But that's the Army all over.)

Later on it came out in orders, that coats were not to

be cut, and tags were issued, so that the coat could be raised

above the knees, like the French pattern.

Fatigue parties had to go back through the mud and shell

holes for rations and water. There was no ration for the first

forty-eight hours, and when the rations did arrive, the "dodger"

and the cigarettes and matches were completely saturated, and the

men had to go without a smoke.

It was a common sight to see men looking around for a tin

of bully or pork and beans, and No. 2880 found some hun tinned meat

which came in handy.

The transport (mules) brought up the rations to a certain

point by night, and then they became man-handled to the trenches.

Often a ration party would come under shell fire, and lose a few

men, and so they became "buckshee" ( if, as sometimes, some of the

rations would be dumped) for the first party that chanced to come

along, while the men in the trenches went short.

Period 3.

-17-

During the trip in at Flers, Fritz used a great deal of gas

shells, and got a few casualties. There was no shelter for the

Entrenching tools came in useful for scraping a funk-hole,

when this was done, the bank collapsed, and so later on it

came out in orders that "men must not weaken the parapet, by digging in the side of the trench, but must stand out in the weather.

the "heads', always had their dug-outs.

One afternoon during a "strafe" No.2880 and Cap. White

had had a narrow escape. A shell burst on the parapet, and a

piece of "buckshee" buried itself in the bank, and missed these

(going between them) who were standing close together, by a

few inches.

During a gas alarm, one night, No.2880 was roused up by

No.2929, and had a trying time trying to find his cap comforter

in a pool of water, with a gas mask on.

The roads behind the line were in an awful condition at

times with mud and shell holes, and gangs of men were employed

to keep them swept and repaired. Sometimes the Aussies did this

work, while out of the line for a rest, and it was not a pleasant

job during the winter months.

Flers, soon convinced Charles D----- that he could not

stick to trench life any longer, and the doctor thought so too,

so they found a job for him at the Comfort Funds Deport, to which

he held on until the war finished. But, (as he will tell those

who ask) his job was not all beer and skittles.

In a shell hole, and lying in No-Man's Land, was a hun

bombing team, five of them and all dead, with their faces turned

black with the frost. Evidently they had been surprised and shot

down. One man still held a "potato-masher" (hun stick bomb) in

his hand.

No. 2880 eager for souvenirs, cut off a set of brass buttons

from off the tunic of one man. One the buttons was a double-

headed eagle. But he soon "got the wind up", and got rid of them,

for an "old soldier" informed him that if Fritz caught him with

them, he would certainly be shot for loot.

At one stage at Flers, Fritz asked for a four hours' Armis-

Period 3.

-18-

tice to bury his dead. This request was refused, as he had

proved himself not to be trusted, in the past. Instead of

burying the dead, only, he had been found putting in concrete

emplacements for his guns.

At Flers, No.2880 had a septic hand, caused by getting it

torn on rusty hun barb wire. He reported it to the doctor, who

instructed the A.M.C. chap to give a dry dressing, and a couple

of blue pills to place in the water for washing the hand with.

Though the A.M.C. was in a large dug-out, yet he had to go

back to his post and treat the hand himself. It was impossible to

keep the mud away from the wound, and so no progress towards recovery was made, and the hand became painful and swollen.

After coming out of the line, he again went on sick parade.

That morning there was a big route march on, and the Doctor

told the A.M.C. Orderly to apply a dry dressing, and send No.2880

off on the march, and when that was over, to instruct him to report

for treatment. He was sent off on the march but was allowed

to carry no rifle. That night he and No.2929 broke the Army

regulations and walked to a field hospital. The Sergeant Major,

as a special favour cleaned the wound and made a good job of it.

Great numbers of planes were seen in the air at the one time

at Flers. Sometimes as many as fifty or so would be hovering around.

At the back of the line were the kite balloons (or Sausages),

while the Archies (anti air-craft batteries) were placed

almost everywhere.

At night, the hun flares went up, and appeared like a garden

of flowers with bended stalks, lighting up No-Man's Land.

In those days it usually took six hours for a stretcher

bearing party to carry out a wounded man to the aid station.

It was an awful job struggling though, through the mud, and

a pitiful sight to see the mules and horses bogged, with only

their heads above the surface of the mud, left there to die. More

than one man has perished in a similar manner on that Somme.

However the stunt did not come off and the troops moved

back to Hungry Hill, and very nearly returned straight back in to

Period 3.

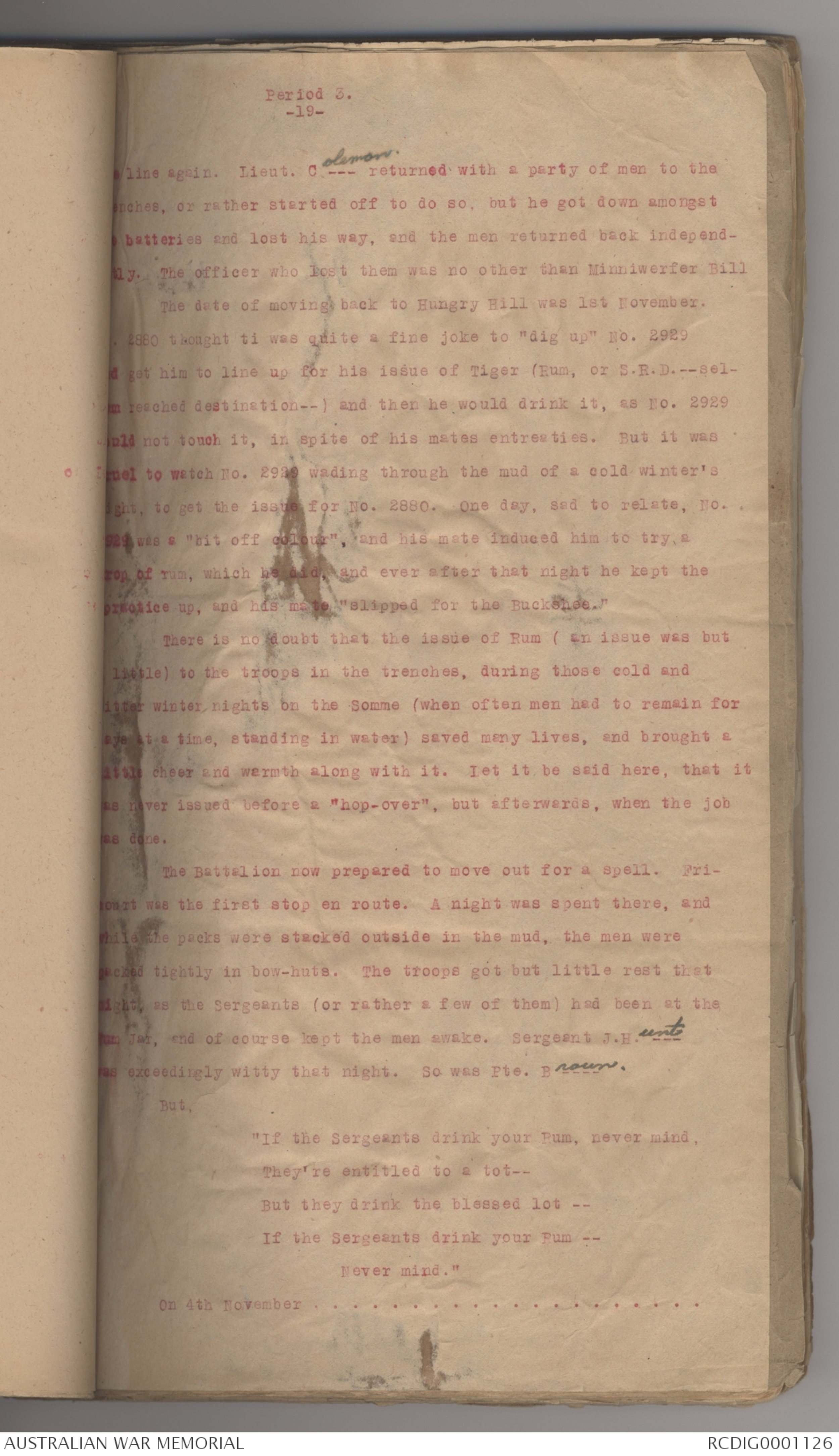

-19-

line again. Lieut. Coleman returned with a party of men to the

trenches, or rather started off to do so, but he got down amongst

the batteries and lost his way, and the men returned back independently. The officer who lost them was no other than Minniwerfer Bill.

The date of moving back to Hungry Hill was 1st November.

No.2880 thought it was quite a fine joke to "dig up" No. 2929

and get him to line up for his issue of Tiger (Rum, or S.R.D--sel-

reached destination--) and then he would drink it, as No. 2929

would not touch it, in spite of his mates entreaties. But it was

cruel to watch No.2929 wading through the mud of a cold winter's

night to get the issue for No.2880. One day, sad to relate, No.

2929 was a "bit off colour", and his mate induced him to try a

drop of rum, which he did, and ever after that night he kept the

practice up, and his mate "slipped for the Buckshee".

There is no doubt that the issue of Rum (an issue was but

little) to the troops in the trenches, during those cold and

bitter winter nights on the Somme (when often men had to remain for

days at a time, standing in water) saved many lives, and brought a

little cheer and warmth along with it. Let it be said here, that it

is never issued before a "hop-over", but afterwards, when the job

was done.

The Battalion now prepared to move out for a spell. Fricourt

was the first stop en route. A night was spent there, and

while the packs were stacked outside in the mud, the men were

packed tightly in bow-huts. The troops got but little rest that

night as the Sergeants (or rather a few of them) had been at the

Rum Jar, and of course kept the men awake. Sergeant J.Hunt

was exceedingly witty that night. So was Pte. Brown.

But,

"If the Sergeants drink your Rum, never mind.

They're entitled to a to --

But they drink the blessed lot --

If the Sergeants drink your Rum --

Never mind."

On 4th November . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

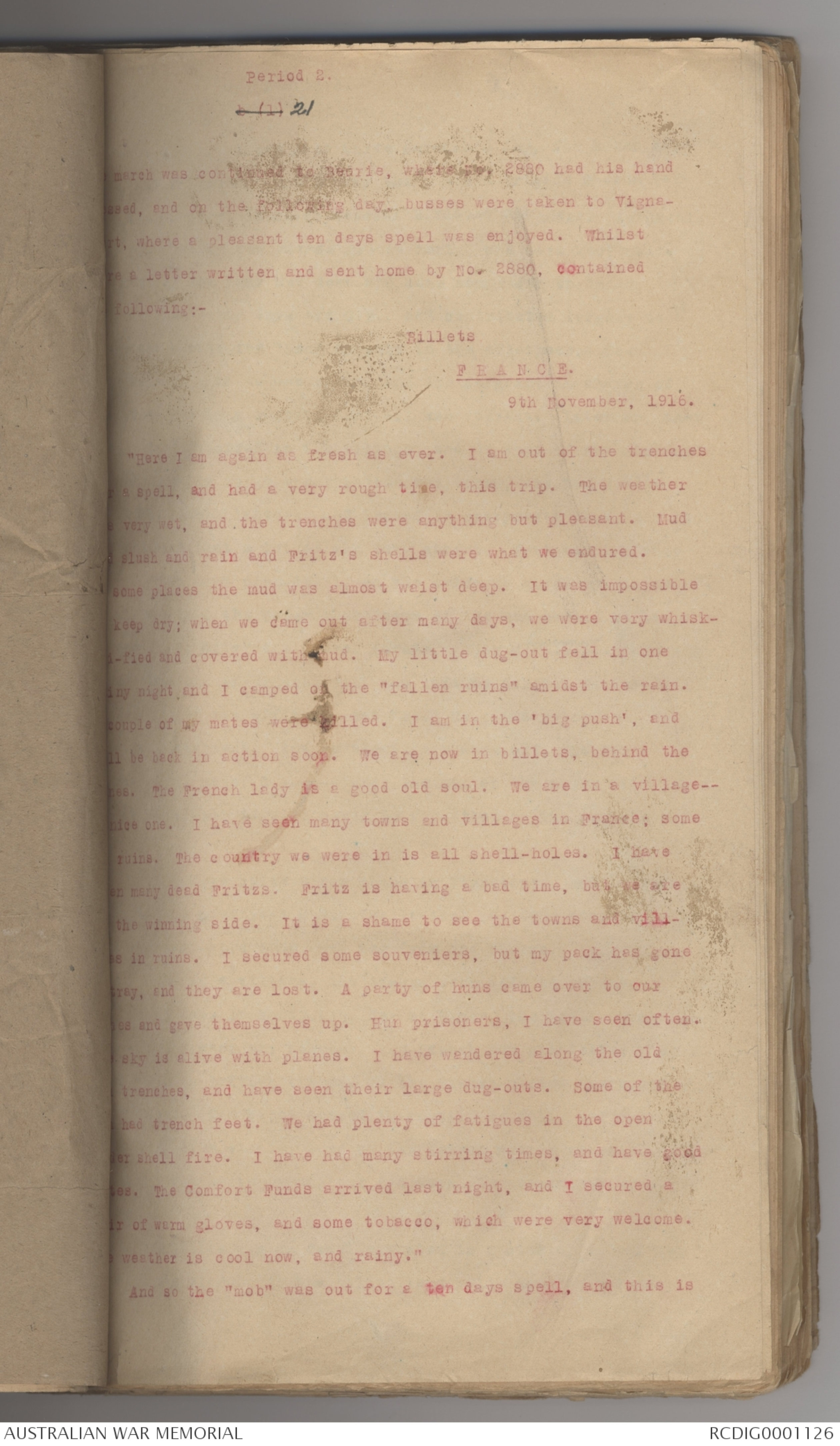

Period 2.

b (1) 21

march was continued to Bearie, where No. 2880 had his hand

dressed, and on the following day, busses were taken to Vignacourt,

where a pleasant ten days spell was enjoyed. Whilst

there a letter written and sent home by No 2880, contained

the following:-

Billets

F R A N C E.

9th November, 1916.

"Here I am again as fresh as ever. I am out of the trenches

a spell, and had a very rough time, this trip. The weather

is very wet, and the trenches were anything but pleasant. Mud

slush and rain and Fritz's shells were what we endured.

some places the mud was almost waist deep. It was impossible

to keep dry; when we came out after many days, we were very whisk-

er-fied and covered with mud. My little dug-out fell in one

rainy night and I camped on the "fallen ruins" amidst the rain.

A couple of my mates were killed. I am in the 'big push', and

will be back in action soon. We are now in billets, behind the

lines. The French lady is a good old soul. We are in a village--

a nice one. I have seen many towns and villages in France; some

in ruins. The country we were in is all shell-holes. I have

seen many dead Fritzs. Fritz is having a bad time, but we are

on the winning side. It is a shame to see the towns and villages

in ruins. I secured some souvenirs, but my pack has gone

astray and they are lost. A party of huns came over to our

lines and gave themselves up. Hun prisoners, I have seen often.

The sky is alive with planes. I have wandered along the old

trenches, and have seen their large dug-outs. Some of the

men had trench feet. We had plenty of fatigues in the open

under shell fire. I have had many stirring times, and have good

The Comfort Funds arrived last night, and I secured a

pair of warm gloves, and some tobacco, which were very welcome.

The weather is cool now, and rainy."

And so the "mob" was out for a ten days spell, and this is

Judi Gayfer

Judi GayferThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.