Memoir of John Shakespear Bartley, 1916-1919 - Part 7

-8-

often had a lot of stock phrases and would often remark "You're

going to France, I'm not", and then someone would roar out a

suitable reply. Freddie would wax warm and shout out "The man who

said that, one pace to the front--one pace to the rear--quick march!"

Some one heaved a brick through the sergeants window one night.

On parade next morning he appeared with the brick in his hand and

said "The man that threw this brick--one pace to the front--one

pace to the rear--quick march! No one stirred. Then walking up

to the adjutant he said "It wasn't 'B' Company, Sir, I asked them."

(Incidentally it was "B" Company.) He had quite a mania for inspection

parades and was always adjusting the men's equipment, and

was constantly calling out "Will you never learn." He insisted

on standing in the ranks as stiff as a poker, and no man was permitted

to raise a hand to brush a fly away. "Put that hand down", he

would roar out many times a day.

One day he told the men to take a lesson from the Spartans.

"Those Spartan youths stood unflinching in the ranks while ferrets

gnawed at their breasts" was what he "put over", but he forgot that

he was speaking to Australians and not Spartans.

He was not too liberal on granting men permission to leave the

parade ground during smoke-oh at eleven, and one day he came up

the lines armed with a large stick and caught a lot of men drinking

water, and drove them all out, as one of his hard laws was "No drinking

during parade hours."

One afternoon a General came along to lecture the N.C.Os. The

Serg-Major (called by the boys "The, black snake"), who was no favourite

at the time (but afterwards in ^(ALCORN) in France as an officer he was

quite a different man, for it is wonderful how common danger brings

men on to a level) was the only N.C.O. left in charge of the whole

company. Of course the boys played up, and it was a sheer impossibility

for this man to make them drill. So he hit on a plan of

marching them round and round in a circle, up and down a bit of a

hill. It was funny. All the time the troops were singing "Australia

will be there", and letting him know in plain language what they

thought of him. Then he picked out a few of the men who were his

own particular mates and told them to sit down. As a result others

PERIOD 2.

-9-

sat down un^invited, and so the fun went on. Nos. 2880 and 2929 fairly

enjoyed themselves that day. The parade hour being finished

the S.M. marched the men back to the Orderly Room, and reported

the matter to Freddie. "You men have been having a big joke with

the Sergeant-Major", he said, "Very well, I have plenty of time.

I've met men like you before. About turn! And off went the Company

back again for a march round the paddock, which lasted quite

a long while, and when the men were tired, he formed them up in a

circle, and said "Now I've got something to read to you", and he

commenced to read a great bundle of literature about poison gas.

But he received many interjections from the men. Finally one man

fainted from sheer exhaustion, and this put the wind up Freddie,

and he said"I think you've had enough, now." and one chap called

out. "Yes! You old -----". "Step out the man who said that

roared old Freddie; and the men (Mac) did "hop out" and faced him.

"What did you say" Roared Freddie, "I said, "Yes, Sir." replied

Mac. And that ended the days sport.

On another occasion Billy Hughes came to inspect the Company

and all the other Aussies on the plains, and the order was that

all companies were to carry water-bottles and haversacks containing

a meal. Freddie took fine care that his company marched out

with nothing, saving a rolled overcoat and plain belts. Upon

arrival at the place of inspection it rained heavily. The troops

were kept standing in the pouring rain for hours, and no one was

allowed to unrol a coat for it would spoil the effect of the march

past, they were informed. As a result there was much murmuring

in the ranks and Mac, (referred to a few lines back) put his on.

But his name was taken and he had to take it off.

The review came off O.k. and later on, an officer noticed that

"B" Company had no rations, whilst all the other companies were

eating their dinner, which consisted of bread and tinned salmon.

It was noticed that Freddie was sent to the rear of his company

on the march back and Captain KATE (a good fellow) took

command. After this Freddie was missing for four days. The rumour

had it that he had to face a court-martial.

"You know", he often said "that I don': belong to the 30th

Battalion.

Period 2.

-10-

was only lent." The boys used to reckon that his own crowd must

have turned him down, but wished that he would return to his fold

again.

1t was hard to obtain leave to London or Salisbury, during

Freddie's reign. A man would put in his application and be paraded

before him and generally his reply was "I have a son, wounded

in London, and I can't get leave to see him. You know what a good

soldier does. About turn! Quick march! back to your huts." No

wonder that men used to take French leave. Especially when it began

to be noticed that Freddie often did go to London. When he returned

at night he would go sneaking along the sentry posts to find

out whether the guard was doing his duty.

One night he returned very late and walked up to sentry who

let him come on without the usual challenge. Not recognising him,

he said "What are you looking for, mate?" That sentry was soon in

"clink", and the next day, the company heard all about it, and special

instruction in guard and sentry duties were given. He put another

tale over on them. He related how he once put a guard over

seme huns (didn't say where it was though) and upon his coming

round for inspection, he found the guard asleep with the huns.

No. 2880 applied for leave for Salisbury for the week end. It

'was on a Saturday, and the next day was to be his birthday. Before

signing the pass, Freddie made him wear a belt and a haversack so

that he would be assured of No. 2880 carrying his shaving gear.

No. 2880 had a fair time in Salisbury, visiting the famous Cathedral

and so. 2929 well knows how he came back in a motor car, owing to

the busses breaking down.

Freddie did not get on too well with "La Bassee" who blamed

him for the failure of a dummy stunt on one occasion near the Fargo

Hospital.

Most of these training stunts wereccarried out at night, and the

first one was responsible for alarming the people in the hospital

owing to the noise made by the bayonet charge.

On another occasion a gèneral inspected the company in the pouring

rain, and the troops were wet through. After the inspection

Freddie marched the men straight out on to the usual parade ground

-11-

commenced his fancy orders, such as "a quarter left wheel" and

two thirds of a "right turn", etc., and got quite wild because there

was a little hesitation and bungling about the carrying out of the

orders. "Because I give you an order, that's not in the book, you

can't do it", he roared. "Will you never learn?" However Captain

Worrall (La Bassee) rode up and ordered the Company into the huts

to get dry clothing.

La Bassee was greatly amused that day, while waiting for the

General to come along. It was always waiting on those occasions.

They would have the troops up at daylight, and then would follow a

great rush to get cleaned up, and then breakfast, and then the usual

wait for hours, standing with pack-up on a parade ground, waiting for

the "heads" to come along. Sometimes they would not come at all,

and when they did come the whole ceremony was over in a very little

wnile.

But this day the boys started up a song which ran like this:

"Waiting, waiting, waiting.

All day long we are waiting,

From Revielle to lights out

We're waiting all day long.

When we're dead and in our grave

We'll jolly well wait no more."

In the second verse the word "starving" was substituted for "waiting."

This amused La Bassee very much. Freddie had a horror of the

Bugle Band, which he said possessed no harmony. When the troops

marched in from parade, this band usually was stationed at a point

they had to pass, and then played them in.

On passing this band he would place his hands over his ears, to

show his contempt, and roar out "Stop that ---- band". But they played

on. Eventually he led his company in, round the other way, and

left the band playing to the flies.

"What I can do, you can do," he often said and for an old man

was quite an athlete. Playing Prisoner's Base, one day, it was noticed

that not one man in the Company could catch him on the run.

He wore an awfully shabby uniform. The boys reckoned that he

was too mean to get a better one, till he was compelled to.

Period 2.

-12-

He was greatly hurt, when his brother officers told him, that

his pack was filled with paper, while on the march, so he turned

out his pack to show them it was "dinkum."

Another amusing officer at Lark Hill was "Mad Mick". He was

quite a character and very witty. One morning whilst engaged in

inspecting the men on leave for London, he paused in front of No.

2929 and complained about his bulging pockets, (which were full of

books, etc.,) and roared out in his own peculiar way, "Call yourself

a soldier!" "One - One-two. Step to the front and fix those

pockets.

There were three absentees from the parade on one occasion,

and upon the N.C.O reporting some, he replied, "Well, Sergeant, I

don't know where the devil they are. They must have joined the

Flying Corps last night and are still on the wing."

No. 2929 unfortunately got into holts with the Quarter Master,

who was loved by very few, and was Freddie's right hand man. The

cause of the trouble was that No. 2929 refused to sweep out the

hut. He had every good cause to do so. The Q.M. demanded his

name, but he would not divulge it, and went on parade. Later on

however, his name was supplied by another party and the matter "blew

over".

But as far as No. 2929 was concerned, the incident will ever

remain with him. According to all accounts it was just as well

that they never met in France.

However this "Quarter-bloke" took care to dodge the line for

a long time, and he was not in the line long, when he became wounded.

The circumstances of which will be related as this sketch proceeds.

A period of four days leave was allotted to all troops from

overseas, in which to have a look at London. Fancy "seeing" London

in four days!

So on 7th July, 1916, after a run of over eighty miles from

Amesbury, they both found themselves on Waterloo Station, and were

marched down to Head-quarters at Horseferry Road, Westminster.

Diggings were found at Peel House in Regency Street, Westminster,

which place was known as King George and Queen Mary's Club, for

soldiers of the Empire. The Club was a grand place to stay, being

-13-

close to the famous old Abbey. It was at Peel House (once a police

barracks) that soldiers from all parts of the Empire were to be met

and it was close to the Y.M.C.A. building (afterwards the War Chest

club.)

London, with its old buildings, once white but now dusty with

ege, was at first sight rather disappointing. But the great age

of the city, is one of its most beautiful charms.

Their first visit was to Madam Tussaud's famous Wax-works

situated at the top of Baker Street. Here were seen figures of

Royalty, statesmen, poets, etc., and a few beautiful tableaux.

They were escorted around the building by four Jack Tars from off

a submarine.

Here aselsewhere they were admitted free of cost. The place

is full of beauty, and on entering a room, one is undecided whether

the figures are really wax. Many get "had" with the policeman at

the door. How No. 2880 got had (at a later date) in another portion

of the building, will be told later.

Leaving Madam Tussaud's, the pair wandered along the old

Tottenham Court Road, and began to grow weary of saluting, when a

Tommy Officer approached and handed them a couple of Theatre-tickets

for a show at the Savoy-Theatre, Strand. Upon investigation it was

found that the tickets were valued at 10/6 a piece, and so after

"shaving up" and "Kiwi-ing" their boots, they taxied down to the

theatre in great style. Upon arrival, an usher showed them the way

to go, and a young lady attendant then showed them to their seats.

Here was an almost embarrassing situation, for two rough Australian

soldiers were occupying seats surrounded by the Elite of England

(at least they imagined so), and it was a quite noticeable fact,

that their presence caused no little attraction, judging by the

manner which several of the ladies had, of looking under their

fans at them. Upon presenting the programmes, the young lady

remained immediately behind the chairs, as if in anticipation of a

"tip". As tipping appeared to be a great custom in England. No.

2880 fully thought that a tip was awaited, and actually was about

to hand over a shilling (two-pence seemed to be the usual tip in

London), when the young lady said, "Would you....

Period 2.

-14-

like to give me a shilling, please Sir?" (They were good on the

Sir.) A little surprised, he said "Certainly, Miss."

A little later, all doubts were removed, for the programmes

cost a shilling. In Aussie, at that time it was customary to give

away Programmes. The play was enjoyed, but what it was all about

has long been forgotten. But that night, and the walk back to

Peel House; shall it ever be forgotten? Lost in London at midnight

was the situation. As a matter of fact they managed to lose themselves

every hour of the day, but then it was quite a simple matter

to jump into a taxi and call out "Peel House, driver", and all

became clear again. But this Saturday night, all efforts to get

a taxi were unavailing, as those conveyances were all engaged. It

seemed as if the air was full of whistles, calling up Taxis.

A constable advised them to walk home, and directed them.

After walking and enquiring for no less than one and a half hours,

they eventually arrived home. All the time they were only about

twenty minutes walk from the theatre. No. 2880 has done that same

walk many a time since, and could not be lost there now.

That night they asked many police for guidance, (the London

Police were a fine and obliging body of men), and on nearing Peel

House they fell in with a possee of constables going on duty, who

sook them right to the door.

Hyde park was visited next day, and after passing Charring

Cross Hospital, they wandered down to the old Museum of antiquities,

opposite the Horse Guards in Whitehall. Here were seen curios,

some of them thousands of years old. At the entrance were some

anchors, which formerly belonged to some of the vessels of the

Armada. The inside revealed Chinese cages, Tel-el-Kebir relics of

1882, a model of the Ship "Queen Mary," cannons of wrought iron of

the 15th Century, Chinese guns and guns of all kinds from the earliest

day to the present, guns captured in the Indian Mutiny of

1857-8, Relics of Waterloo, Kruger Sovereigns, Armour of Jameal,

Relics of the Royal George, Relics of Campaigns in Africa and the

Soudan, etc.

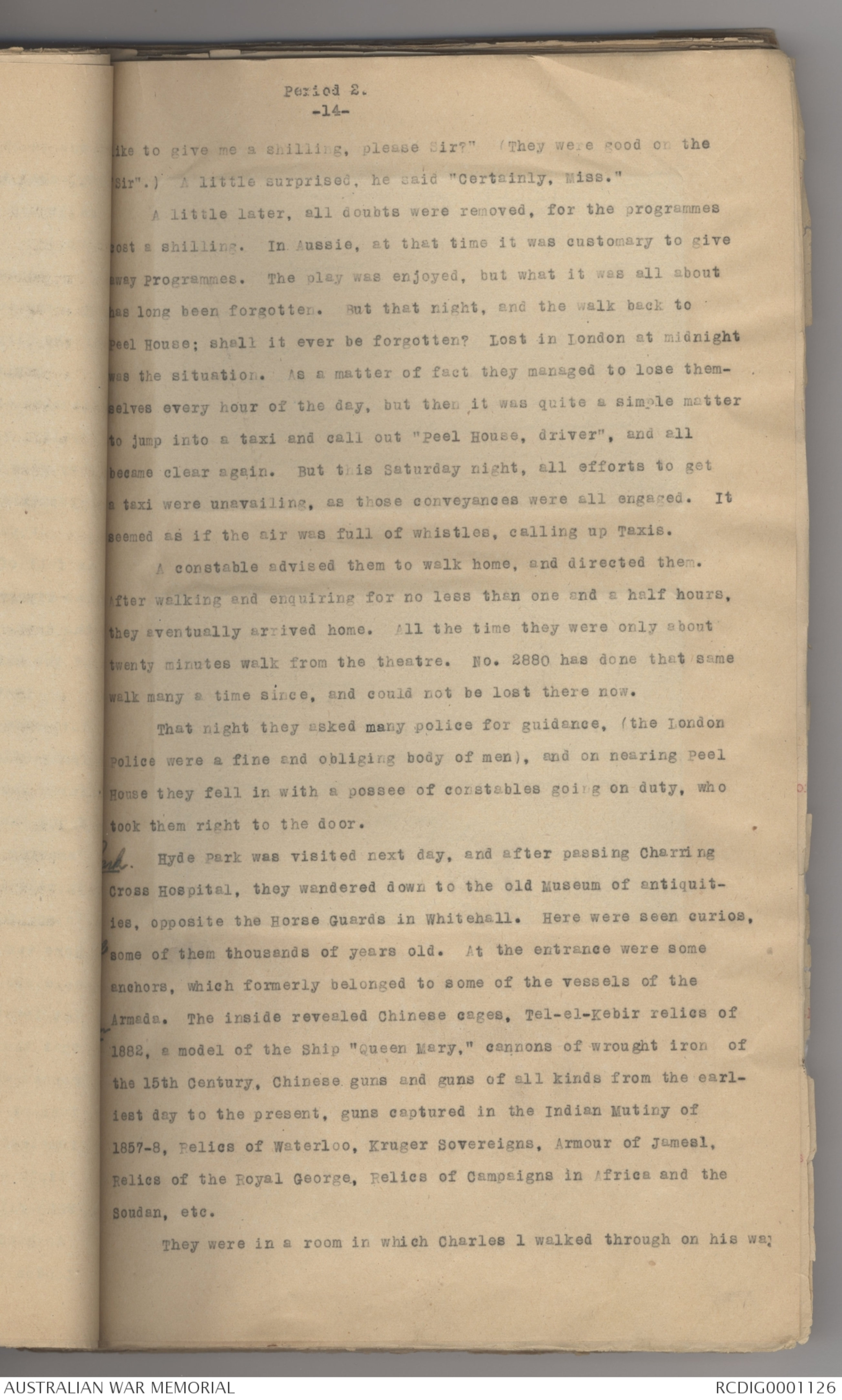

They were in a room in which Charles 1 walked through on his way

Black and white postcards, see original document

St John's Chapel in White Tower,

Tower of London and

Horse Armoury.

Tower of London

-15-

to execution on 15th January, 1649, and were also in the banqueting

hall of James 2.

Also on view was General Gordon's revolver, Blucher's saddle

and Kitchener's field Marshal's Baton. There was a lock of Napolean's

hair, and the Skeleton of the grey horse he used to ride

to Egypt.

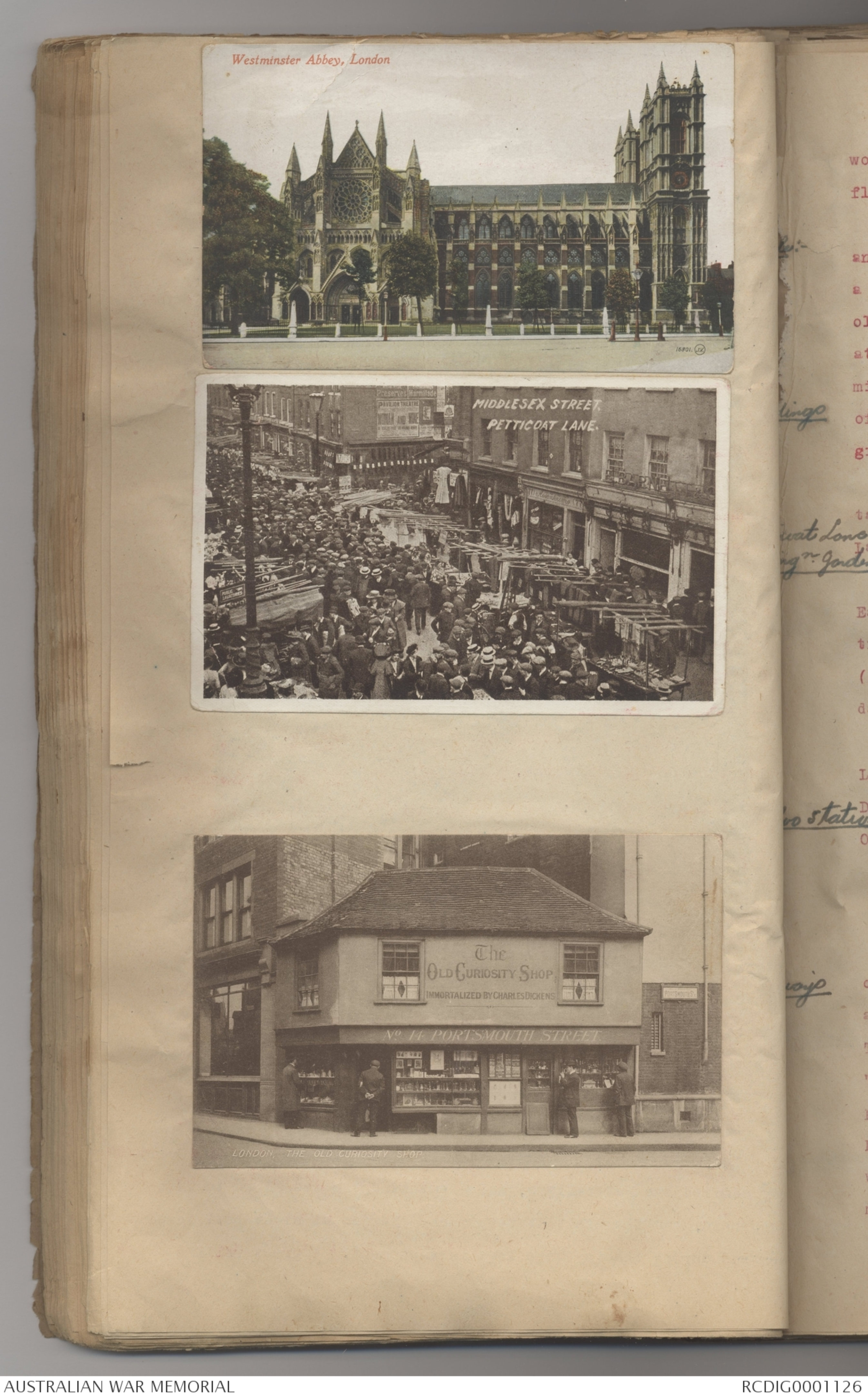

One day they wandered along to Trafalgar Square, Leicester

Square, St. James Park, Strand, and by the Houses of Parliament. (But

later on No. 2880 came to know these places like a book, and much

more will be said later. No. 2929 on his later leaves went to the

North of England, Yorkshire, but somehow for No. 2880, London had

a mysterious power of attraction.)

They noticed many things. Saw few trams and a great underground

system of tube-railways.

On July 8th, they wandered along to Buckingham Palace and saw

the guard change, and met a Tommy who showed them around a bit.

Wandering along Whitehall, they saw the Horse Guards and were told

that the officers were mostly Lords and Earls,

What struck them most was the statues of London, the beautiful

architecture of the buildings, which were once white, but now blackened

with smoke and dust.

Passing through Pall-Mall and having a look at Marlborough

House, they finally found themselves at the gates of the British

Museum, where they were informed by a policeman that that institution

was closed during the war, and advised them to take a look at

Tower.

Catching a bus (and it is said that the best way to see London

is on top of a bus) they very soon alighted at the Monument, which

marks the spot where the Great Fire started in 1666. Close by was

the Tower and London Bridge.

A little later the Art Gallery was visited.

The courteousness of the English people was remarkable. Everybody

admired the Australians, and great kindness was shown to them

everywhere, and they felt it very much. London at night bewildered

them and during the day were lost in amazement. A great rolling

3 photos - see original document

Transcriber 30666

Transcriber 30666This transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.