Memoir of John Shakespear Bartley, 1916-1919 - Part 2

-6-

Those in camp at the time can never forget John Willis, the C. of E.

tent orderly, who really deserves mention for the good work he did

as a pianist, and for his popularity with the men.

It was characteristic of the troops to express their appreciation

of the various items rendered at these concerts by whistling

and of stamping feet, and calling out "What do we want?" And then

the answer "We want more." There is no doubt that the artists

enjoyed those concerts as much as the troops themselves.

So life went on smoothly till 17th February, when an unfortunate

thing happened. A great strike took place. The less said about

that the better. Since that day many of those lads who caused

trouble that day have given their life for their country, and so

let us forget all about that strike.

The result was that the authorities saw the danger of concentrating

too large a body, of troops near Sydney, and hit on a scheme

of forming more country camps.

Previous to the riot, there was a whole series of minor disturbances,

principally directed on the Greek shops in the City.

As a result of the riot, No. 2880 was fined 5/- for being

A.W.L. as he went home that day.

Another result was that they received orders to leave the camp

and proceed to Liverpool.

A few days before the move came off, a night march was arranged

to be combined with night operations. The route lay across the

scrub in the direction of Liverpool camp. Being in column of fours,

the long line of men could be plainly seen moving towards Liverpool

at dusk, and No. 2880 jokingly remarked to the man alongside of

him that there was a possibility of the other camp becoming alarmed

at their approach and taking for granted that another riot was about

to begin.

Operations had commenced. The troops lined a road and a screen

of scouts were sent forward to explore the wood in front. Very soon

the scouts returned, a little excited, and reported to Major Cook.

that an armed party was lying in ambush in front of them. At first

-7-

The Major ridiculed the idea, but upon investigation this information

proved correct. Explanations followed; Liverpool Camp had seen

them, and suspecting another riot, had sent out an armed party to

prevent it. This was bad enough, but when a leading Sydney paper

published wrong facts, and mis-led the public the next morning, it

was worse. Why always look on the worst side of a soldier? No.

2880 has often asked this question many times during the war.

Life at Liverpool camp, was similar to that of the camp just

left.

One of the things No. 2880 will never forget was those Kitchener

rides on the railway. Instead of paying fares the guard was told

to put it down to Kitchener's account. Later on in Belgium it

was often put down to Foch, and it was awfully humorous to watch

those Belgian guards trying to collect fares from the Diggers.

The spot selected to pitch tents was not far from Meningitis

gully, and at the top end of the camp, and very close to the A.M.C.

They had to pitch their own tents and cut roads. It was here that

No. 2880 first met No. 2929 and both men now found themselves drafted

to the 6th Reinforcement of the 30th Battalion, and on the eve

of proceeding overseas. Their tent mates were Jim FALCONER Billy WATT,

Harry REID, Earnest COOKE, and Arthur FISH (the Flounder).

Of these Jim F. was the only one killed. Soon after reaching

France, he was transferred to the Railway Unit, as cook, until

one day a shell landed in the cook-house, and Jim was no more.

His cook-house was a kind of charitable institution, while Jimmy

was alive, inasmuch that No's. 2880 and 2929 who knew the little

Welshman well, could always get a "hand-out" of rations from Jimmy

when they came out of the line.

No. 2880 last saw him alive at the Bapaume railway station

about May, 1917.

The tent was fairly crowded and Earney COOKE was afraid of

watching a hundred imaginary complaints, as he was awfully fidgety.

The rough camp life did not suit him at all. So in order to get

rid of him, and incidentally to make a little more room and comfort

for themselves, the boys got one chap named Cruickshank, to pretend to

-8-

be awfully ill. As a consequence, the ruse was successful and

Earnest found new diggings in the R.C. tent.

A pleasant association of Liverpool is always connected with

the songs of Billy WATT.

The Major ^Chaseling was not too popular. On one occasion he measured the

men's great-coats with a long stick, and all men were made to wear

long coats. Months afterwards those same men "blessed"him, for in

the line at Flers, the mud was so bad, that the only remedy was to

use the bayonet and cut all coats off a foot from the bottom all

round. This released a "ton" of mud. But, of course, Major C----

never saw France. When the troops were farewelled the same individual

was heard by No. 2880 to say "Some of you lads are going away

to win glory, some of you are going to push up the daisies in France."

True words, no doubt, but what a thing to say to his own men!

Then there was Adjutant COLLIER, Captain SEYMOUR, (nicknamed

Harbour Lights, on account of his singing a song of that name, at

Holdsworthy Camp on one occasion, and who never pronounced his aitches

Lieut. ADAMS ※ (a dinkum man, and a real "stoush" artist) and Lieut.

SNUGHALL (a smart soldier).

The N.C.O's were Serg.-Major Lindsay, a good fellow, Serg. SHEPHERD

who was dubbed as "sheeps-heard", and who became a "notorious" individual,

later on, in France. He was too conscientious for a sergeant,

that was his only "fault", for he was never known to crime anyone,

and he put up with more abuse than any N.C.O. in the A.I.F. But

more of him later.

There was Sergt. BROWN, also a good fellow, Sergt H----,

fine chap and a great Linguist, Q.M. FISHER, Corporal PICKERING, and

Corp. H----, Serg. Fitzgerald

After four days of final leave in March, they finally left

[[ION?]] Liverpool for good, on the 8th April, (and the next day sailed away

[*→*] on the good ship "Nestor" bound for an unknown destination, on

Active Service at last.)

On Saturday, April 8th, 1916, Nos. 2880 and 2929 awoke early,

[*→*] after the boys coming back to camp late, and spending their second

last night in Australia. Some of them "fou the noo". Nearly all

※ YANK.

-9-

that night they were kept awake by Billy WATT'S dopey songs.

About midnight, a perfect din of the kerosene tin band broke on the

air, and combined with the constant discharge of Chinese crackers,

somewhat forbid sleep, as the boys were having great fun. The

crackers seemed like an introduction of Turkish artillery, and the

[[T.?]] revel grew in intensity and fires were lighted along the camp lines.

The din woke the Adjutant, who came along the lines and restored

order. Tents were now dropped on the occupants inside, by practical

jokers outside. So in a jocular mood they sat and talked until

the bugle sent forth its familiar notes of "Get out of bed, you

lazy devils." We all arose in eagerness. A hurried meal, and loading

the heavy kits on the motors, we prepared to go to Sydney for

a public review and farewell. It commenced to rain like cats and

dogs. Arriving at the Central station we made a fine display. In

front was a rattling band. Each battalion carried its own Union

Jack and its own beautiful colours. The blue and gold banner of

the 30th, carried by "Tiny" MATTHEWS that day has floated in many

strange countries since. Many people of different creeds and colours

have gazed on the beautiful colours of our flag. Unfortunately

the man who carried it, returned to Australia later, having

lost both feet as a result of Trench feet, caught on the Somme

during the long cruel winter of 1916-17.

Coming from the station we were struck by the sight of thousands

of people who lined the streets to pay a tribute of their

respect to the lads going far away to fight for home and liberty,

helping the grand old Mother-Land in her hour of affliction, and

to protect their loved ones from the power of the Huns. Sad to

say that some of those lads who marched with No. 2880 that day have

paid the supreme sacrifice. Some passed away through illness at sea,

some lie buried in Egypt and some in England, whilst many lie

sleeping in France.

The line of the spectacular march that day was along College

Street to the Domain. It was a grand sight: the people cheered

them as they marched along. There were crowds of people and the

police had a very hard job to clear the traffic. There were

-10-

several bands en route. The review went off well. It was a

grand sight to look upon the various units all arranged in Review

order, and the colours of the ribbons and bunting further added

to the scene.

On the journey to the Domain the ranks were broken by mothers,

wives, sweethearts, etc., who linked arms with the soldiers and

marched along with them.

This attitude broke the ranks and from a military aspect

spoilt the march, but they were only too glad to have the people with

them. No. 2880 was thus accompanied with his sister until a big

policeman separated them at the gate.

After the Review a march to the Show-Ground followed. This

time however, the ranks were absolutely disorganised by people

breaking in amongst the soldiers, and the march thus took much longer

time to perform than was expected. In one respect we were sorry

for this delay, and yet in another glad. "We wanted to have a last

look at Sydney, and by the time we were dismissed" says No. 2880,

it was fairly late." Leave was given and the order was that all

men had to be back in quarters by nine o'clock that night, an order

which very few, if any, attempted to carry out. No. 2880 came

back that night in the pouring rain about midnight, accompanied by

the Flounder. No. 2929 remained in camp.

That night it rained heavily. They were encamped in one of the

grand-stands, and the rain poured through and saturated the blankets,

kits and equipment, and likewise themselves. So, as on the previous

night it was a case of sitting up, and passing the time as

pleasantly as possible.

They were hoping that the public would allow us to march rapidly

to the boat in the morning, as they had kits to carry, but in

this respect were doomed to disappointment.

Falling in at half past three in the morning they moved silently

off, but once outside those gates the whole programme of the

yesterday was repeated. Many of the public had waited outside all

night. Early as the hour was, the ranks were invaded again by

hundreds of people who had relatives going away with the troops.

-11-

No's 2880 and 2929 shall never forget sights of that morning.

All the way to Woolloomooloo Bay, where the transport lay, the

[*nooLoo.*] people came forth to bid them "farewell and good luck boys." The

most touching scenes of all were the final good-byes said at the

boat. Mothers were crying and clinging to their sons. In some

cases it was a sight like this that caused other lads to cry too.

Perhaps out of sympathy, perhaps out of recollection of a mother or

sweetheart not then present. Brave men were going out, perhaps

to die, and many of the farewells taken that morning were the last

on earth. No. 2880 was glad that he had said good-bye to his mother

the day previous. All the same he was thinking of his loved ones,

and of the girl whom he was leaving behind, hoping that after he had

earned the right in France, he would return and claim her for his

very own. As the story goes on we will see how far he was successful.

In some cases that morning it became necessary for the police

to part mother and son, at the iron gates leading on to the wharf.

Until the troops embarked the public were not allowed on the

wharf, but as soon as the gates were thrown open there was a general

rush.

The troops lined the decks of the transport "Nestor" (H.M.A.T.

A71), Blue Funnel Line, and climbed far up the rigging, and the

scene on the wharf will never be forgotten by those who witnessed

it. The wharf was packed, and many a man recognised a familiar face

amongst the crowd, who showed no little signs of excitement, whilst

the band on the wharf played "Auld Lang Syne". As A 71 moved off,

thousands of streamers of all colours, reaching from the ship to

the shore, were snapped. The boats in the harbour "cock-a-doodle-

dooed" (funny word) and as the crowd faded away on that eventful

Sunday morning, the boys on board began to realise that at last

they were on Active Service, and on the high seas, bound for an unknown

destination. Thus April 9th will always be a "red- letter"

day for Nos. 2880 and 2929.

Life on the transport, and a good old boat she was, was just

[*ARD*] O.K. Conditions and food were good. In the Australian Bight rough

No. 83. Gathering Cocoa. Ceylon.

Photograph - see original document

-12-

APRIL 16.

weather was encountered for three days. Many of the lads were

sick, but Nos. 2880 and 2929 managed to avoid this kind of thing,

probably more from sheer good luck than good management.

It was on Sunday 16th April that the Australian shores were

left behind at dusk, and the course now lay across the Indian

Ocean to Colombo.

The Ship's doctor was a grand old Englishman, who was a great

favourite and a real sport, and is well remembered by his songs

at the concerts, especially "Three Jews", and by his splendid

address at sea to the boys on the Anniversary of the Landing at

Gallipoli.

As far as the ocean was concerned, the whole journey of about

13,000 miles to England was as smooth as a harbour-trip on a calm

day. At times the sea was like an immense sheet of glass. The

monotony was broken by a little rough weather, well outside the

famous Bay of Biscay.

Colombo was reached on the night of April 28, after a run

[*[[?]]*] of 17 days from Sydney. It is no exaggeration to state that Colombo

could be smelt before reaching there, and it was not a very

pleasant smell either, I can assure you who take the trouble to

try and read this, and it was not until landing that the truth of

the old hymn "What though the spicy breezes blow soft o'er Ceylon's

Isle", justifies its self.

The "Nestor" stayed there for a couple of days in order to

take in coal and water. It was about nine o'clock at night when

the vessel arrived, and it was a very pretty sight from the deck

to watch the light-houses and the coloured harbour-lights.

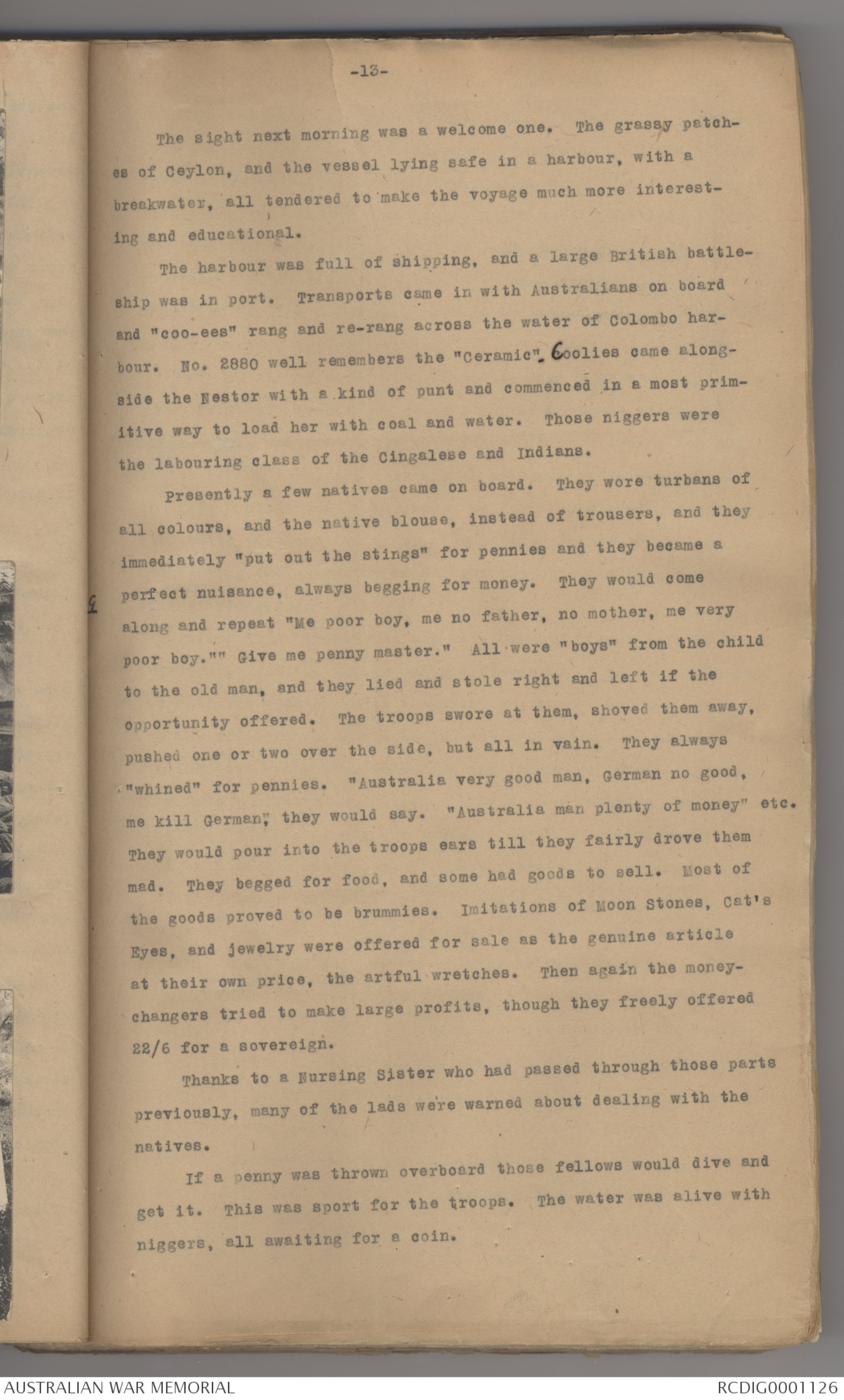

Colombo is the capital and chief trade of Ceylon and does a

great trade in tea.

So filled with curiosity to view the strange people of a

strange land, the troops that night from the high deck gazed down

on the coolies who had come out to meet the ship in boats, mainly

for the purpose of begging, and so made their first introduction

to the Cingalee. A few coppers were dropped into the boats, but

after a bombardment of adds and ends and lighted cigarette ends.

the natives withdrew.

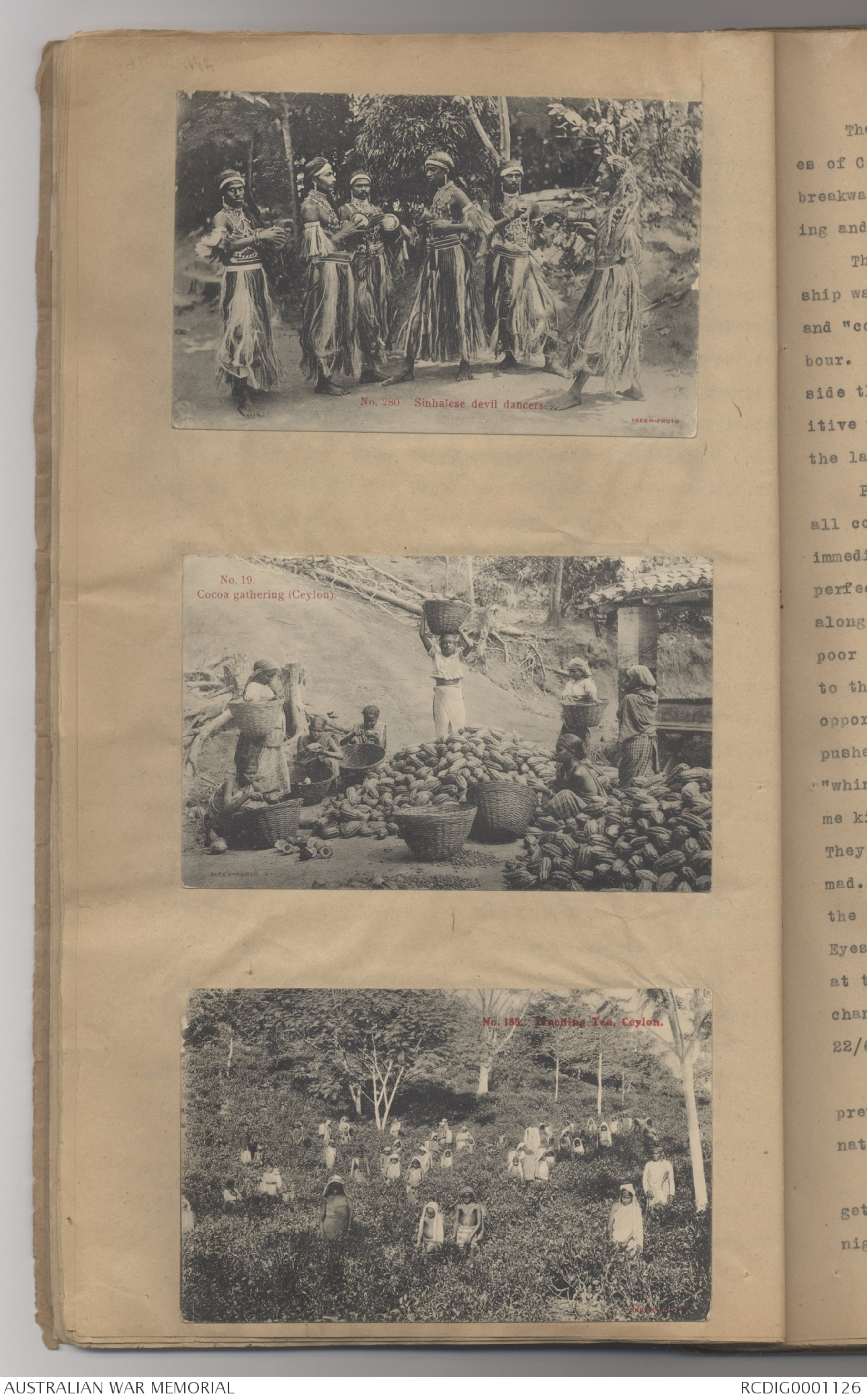

No. 280 Sinbalese devil dancers

Photograph - see original document

No.19. Cocoa gathering (Ceylon)

Photograph - see original document

No. 185. Plucking Tea. Ceylon

Photograph - see original document

-13-

The sight next morning was a welcome one. The grassy patches

of Ceylon, and the vessel lying safe in a harbour, with a

breakwater, all tendered to make the voyage much more interesting

and educational.

The harbour was full of shipping, and a large British battleship

was in port. Transports came in with Australians on board

and "coo-ees" rang and re-rang across the water of Colombo harbour.

No. 2880 well remembers the "Ceramic". Coolies came alongside

the Nestor with a kind of punt and commenced in a most primitive

way to load her with coal and water. Those niggers were

the labouring class of the Cingalese and Indians.

Presently a few natives came on board. They wore turbans of

all colours, and the native blouse, instead of trousers, and they

immediately "put out the stings" for pennies and they became a

perfect nuisance, always begging for money. They would come

along and repeat "Me poor boy, me no father, no mother, me very

poor boy."" Give me penny master." All were "boys" from the child

to the old man, and they lied and stole right and left if the

opportunity offered. The troops swore at them, shoved them away,

pushed one or two over the side, but all in vain. They always

"whined" for pennies. "Australia very good man, German no good,

me kill German," they would say. "Australia man plenty of money" etc.

They would pour into the troops ears till they fairly drove them

mad. They begged for food, and some had goods to sell. Most of

the goods proved to be brummies. Imitations of Moon Stones, Cat's

Eyes, and jewelry were offered for sale as the genuine article

at their own price, the artful wretches. Then again the money-changers

tried to make large profits, though they freely offered

22/6 for a sovereign.

Thanks to a Nursing Sister who had passed through those parts

previously, many of the lads were warned about dealing with the

natives.

If a penny was thrown overboard those fellows would dive and

get it. This was sport for the troops. The water was alive with

niggers, all awaiting for a coin.

KatieL

KatieLThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.