Photostat copy of diaries of Benjamin Bennett Leane, 1915 - Part 8

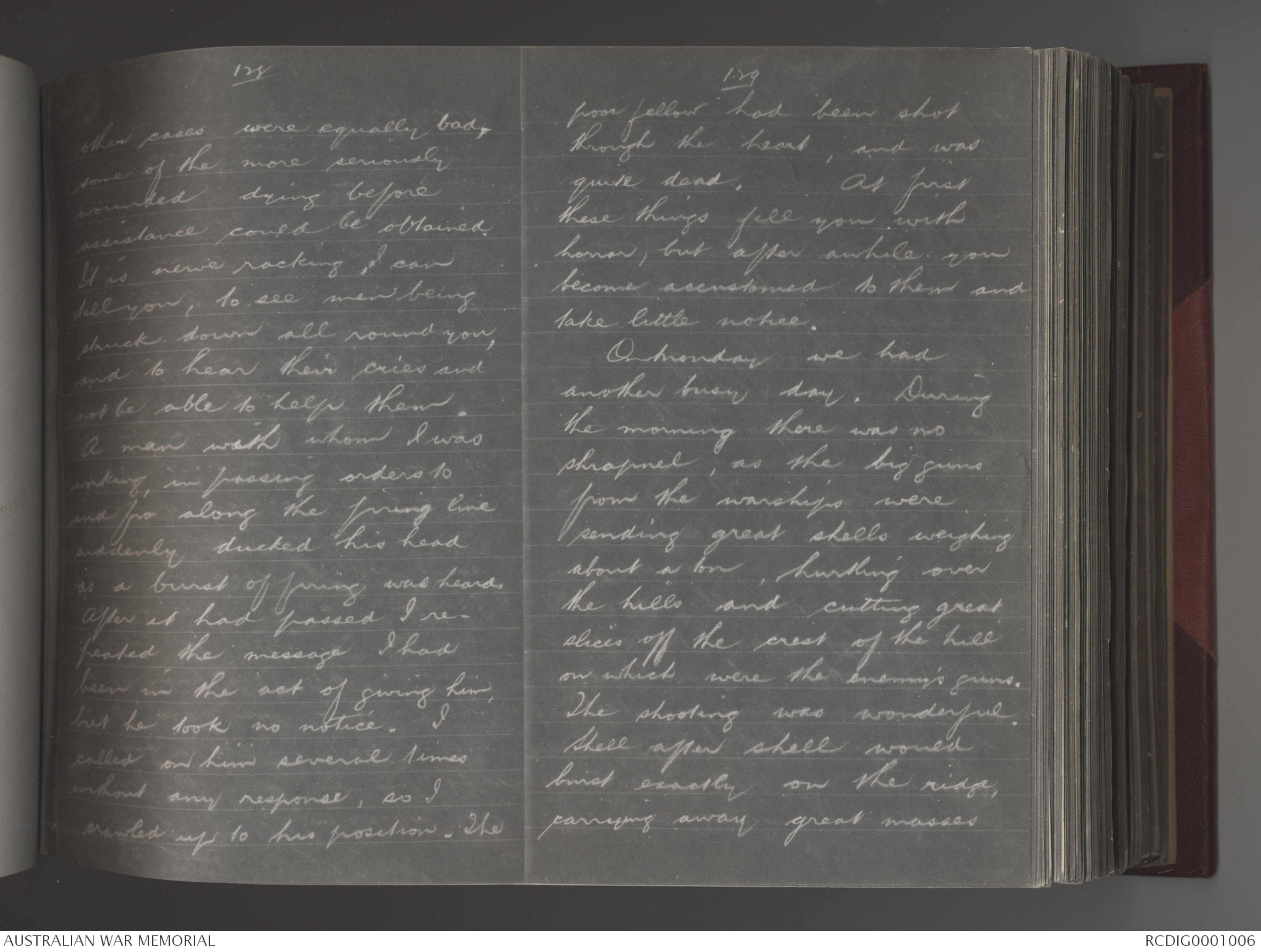

128

other cases were equally bad,

some of the more seriously

wounded dying before

assistance could be obtained.

It is nerve racking I can tell

you, to see men being

struck down all round you,

and to hear their cries and

not be able to help them.

A man with whom I was

working, in passing orders to

and fro along the firing line

suddenly ducked his head

as a burst of firing was heard.

After it had passed I repeated

the message I had

been in the set of giving him,

but he took no notice. I

called on him several times

without any response, so I

crawled up to his position. The

129

poor fellow had been shot

through the head, and was

quite dead. At first

these things fill you with

horror, but after awhile you

become accustomed to them and

take little notice.

On Monday we had

another busy day. During

the morning there was no

shrapnel, as the big guns

from the warships were

sending great shells weighing

about a ton, hurtling over

the hills and cutting great

slices off the crest of the hill

on which were the enemy's guns.

The shooting was wonderful.

Shell after shell would

burst exactly on the ridge,

carrying away great masses

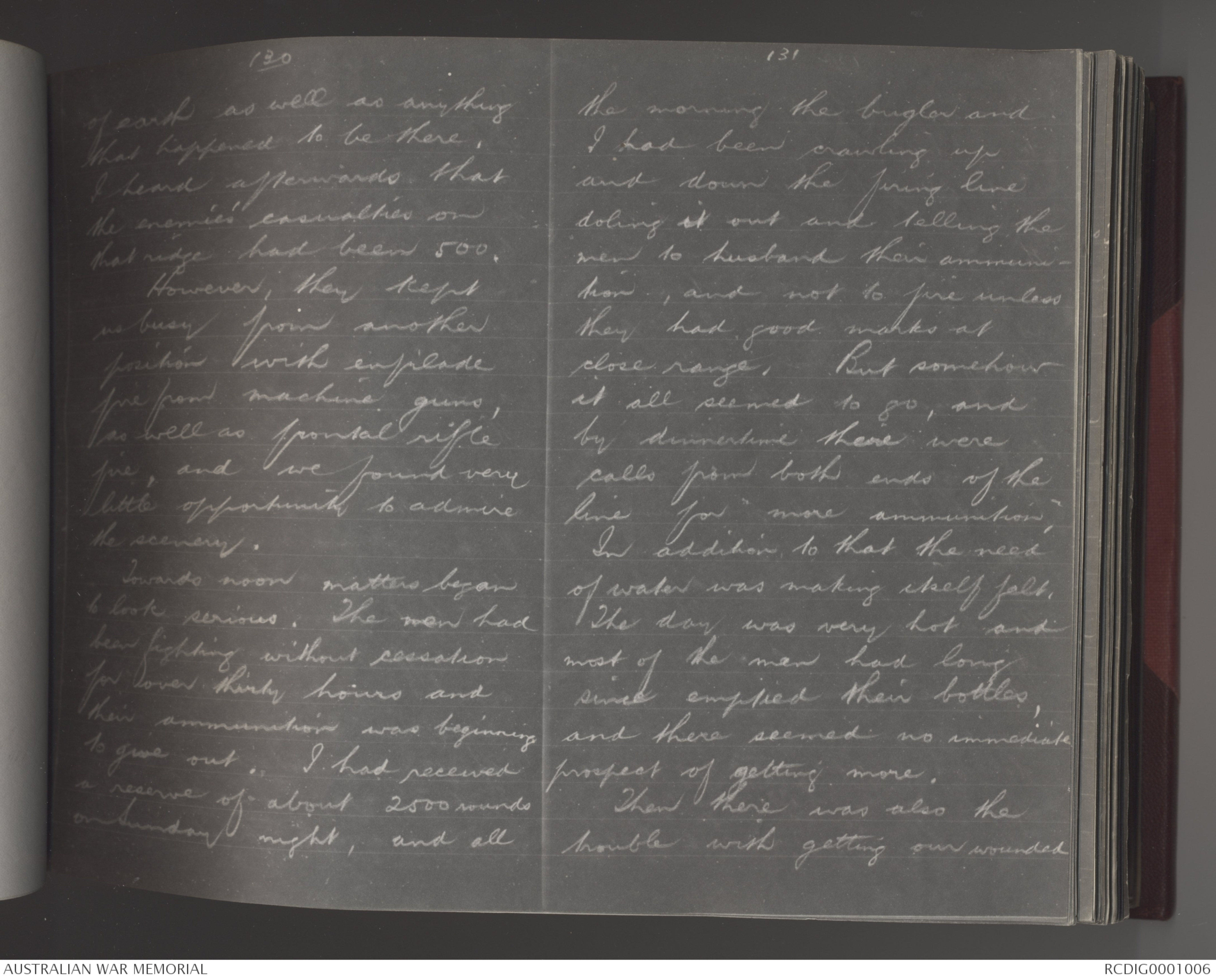

130

of earth as well as anything

that happened to be there,

I heard afterwards that

the enemie's casualties on

that ridge had been 500.

However, they kept

us busy from another

position with explode

fire from machine guns,

as well as frontal rifle

fire, we found very

little opportunity to admire

the scenery.

Towards noon matters began

to look serious. The men had

been fighting without cessation

for over thirty hours and

their ammunition was beginning

to give out. I had received

a reserve of about 2000 rounds

on Sunday night, and all

131

the morning the bugler and

I had been crawling up

and down the firing line

doling out and telling the

men to husband their ammunition,

and not to fire unless

they had good marks at

close range. But somehow

it all seemed to go, and

by dinnertime there were

calls from both ends of the

line for "more ammunition."

In addition to that the need

of water was making itself felt.

The day was very hot and

most of the men had long

since emptied their bottles,

and there seemed no immediate

prospect of getting more.

Then there was also the

trouble with getting our wounded

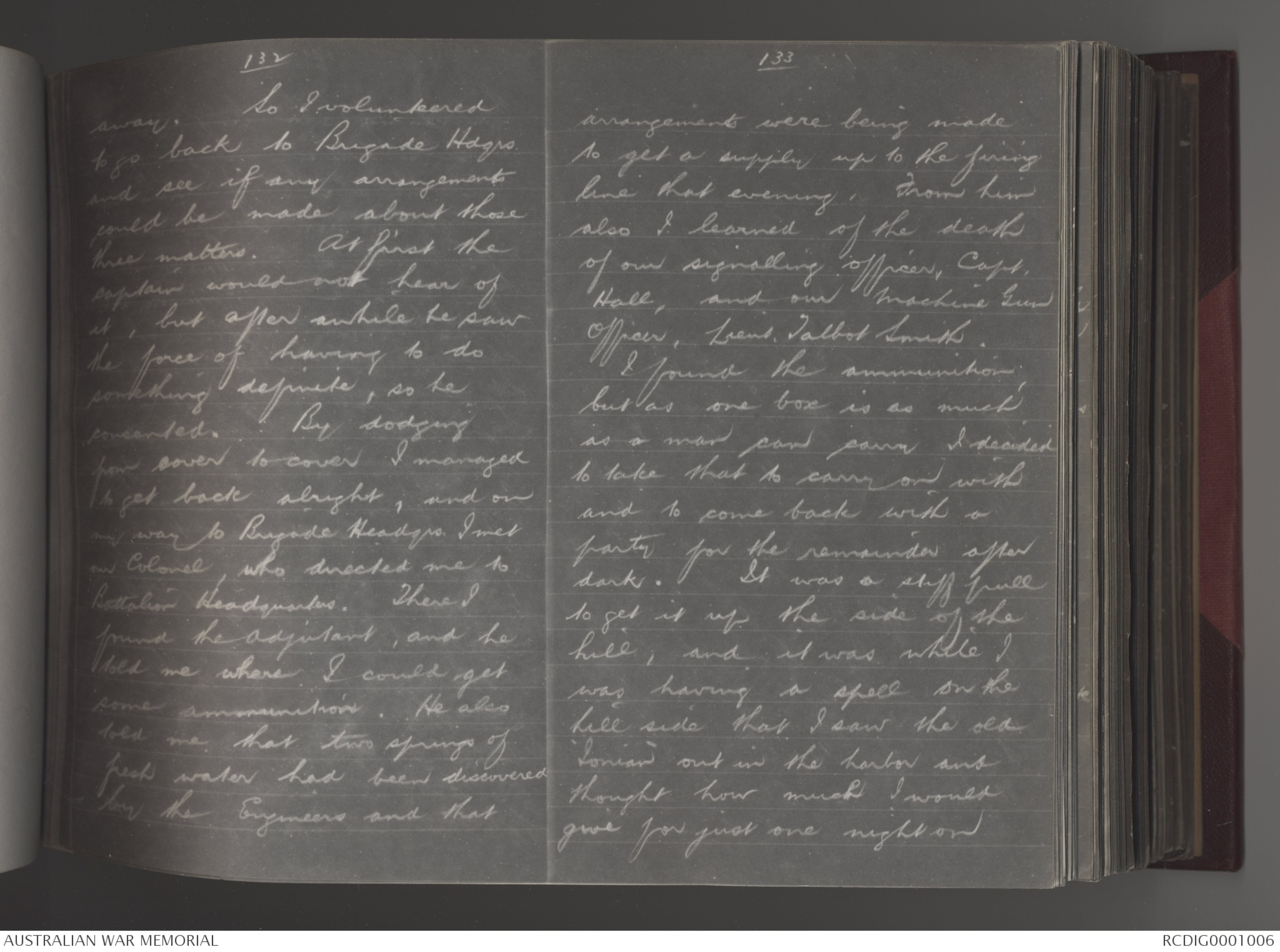

132

away. So I volunteered

to go back to Brigade Hdqrs

and see if any arrangements

could be made about those

three matters. At first the

captain would not hear of

it, but after while he saw

the force of having to do

something definite, so he

consented. By dodging

from cover to cover I managed

to get back alright, and on

my way to Brigade Headqrs I met

our Colone,l who directed me to

Battalion Headquarters. There I

found the adjutant, and he

told me where I could get

some ammunition. He also

told me that two springs of

fresh water has been discovered

by the Engineers and that

133

arrangements were being made

to get a supply up to the firing

line that evening. From him

also I learned of the death

of our signalling officer, Capt.

Hall, and our Machine Gun

Officer, Lieut. Talbot Smith.

I found the ammunition

but as one box is as much

as a man can carry on with

and to come back with a

party for the remainder after

dark. It was a stiff pull

to get it up the side of the

hill, and it was while I

was having a spell on the

hill side that I saw the old

"Ionian" out in the harbor and

thought how much I would

give for just one night on

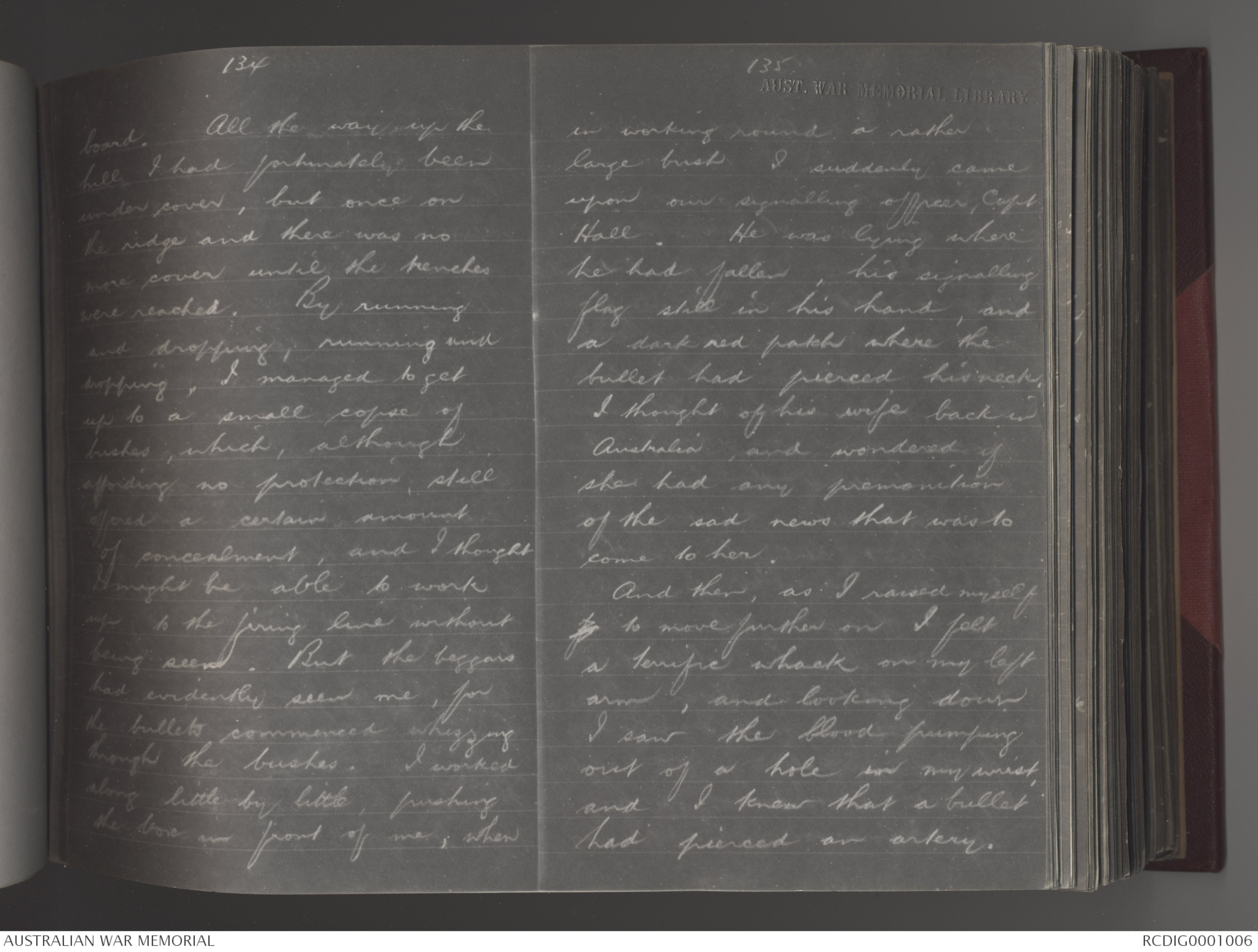

134

board. All the way up the

hill I had fortunately been

under cover, but once on

the ridge and there was no

more cover until the trenches

were reached. By running

and dropping, running and

dropping, I managed to get

up to a small copse of

bushes, which, although

affording no protection, still

offered a certain amount

of concealment, and I thought

I might be able to work

up to the firing line without

being seen. But the beggars

had evidently seen me, for

the bullets commenced whizzing

through the bushes. I worked

along little by little, pushing

the box in front of me, when

135

in working round a rather

large bush I suddenly came

upon our signalling officer, Capt.

Hall. He was lying where

he had fallen, his signalling

flag still in his hand, and

a dark red patch where the

bullet had pierced his neck.

I thought of his wife back in

Australia, and wondered if

she had any premonition

of the sad news that was to

come to her.

And then, as I raised myself

fu to move further on I felt

a terrific whack on my left

arm, and looking down

I saw the blood pumping

out of a hole in my wrist,

and I knew that a bullet

had pierced an artery.

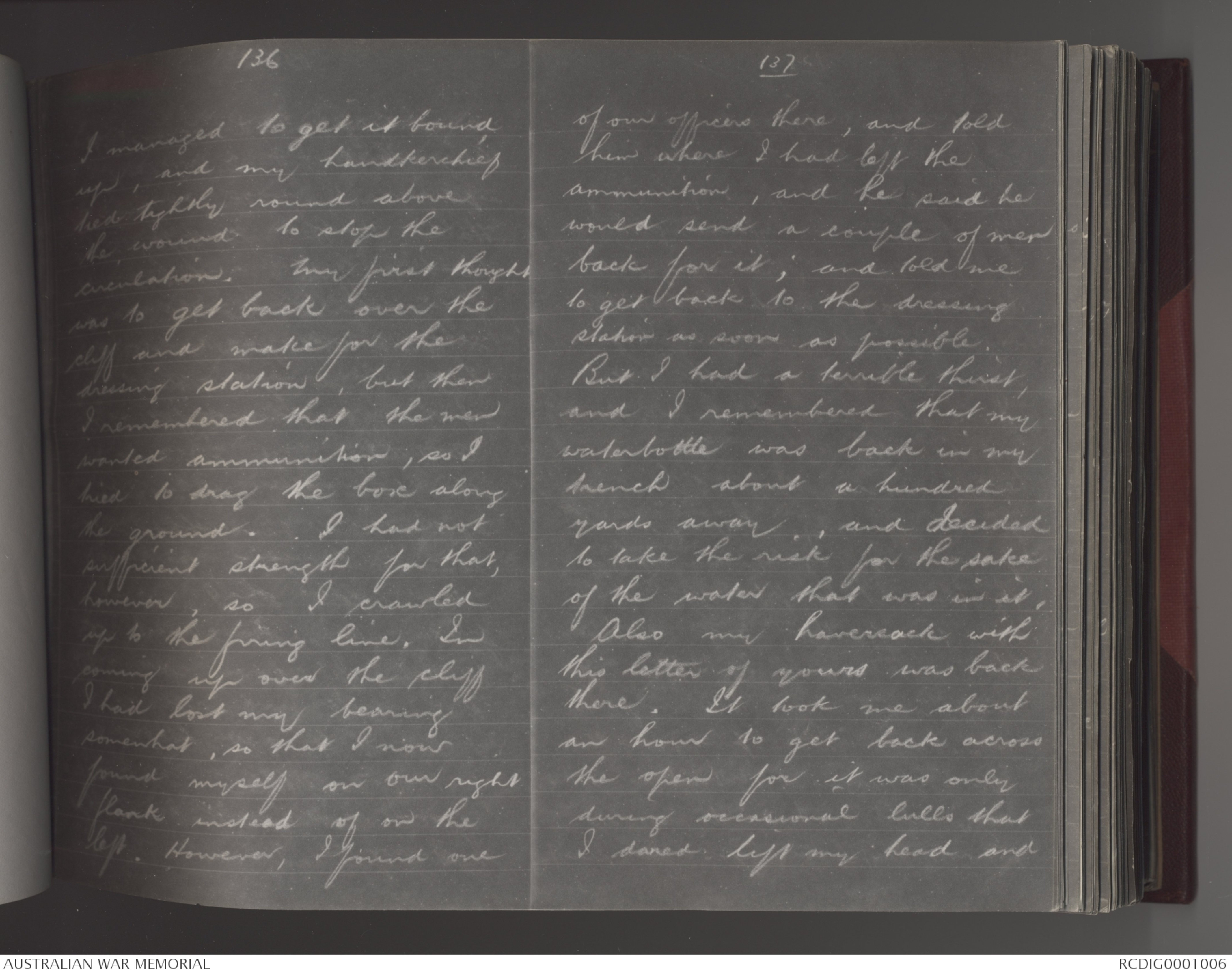

136

I managed to get it bound

up, and my handkerchief

tied tightly round above

the wound to stop the

circulation. My first thought

was to get back over the

cliff and make for the

dressing station, but then

I remembered that the men

wanted ammunition, so I

tried to drag the box along

the ground. I had not

sufficient strength for that,

however, so I crawled

up to the firing line. In

coming up over the cliff

I had lost my bearing

somewhat, so that I now

found myself on our right

flank instead of on the

left. However, I found one

137

of our officers there, and told

him where I had left the

ammunition, and he said he

would send a couple of men

back for it; and told me

to get back to the dressing

station as soon as possible.

But I had a terrible thirst,

and I remembered that my

waterbottle was back in my

trench about a hundred

yards away, and decided

to take the risk for the sake

of the water that was in it.

Also my haversack with

this letter of yours was back

there. It took me about

an hour to get back across

the open for it was only

during occasional lulls that

I dared lift my head and

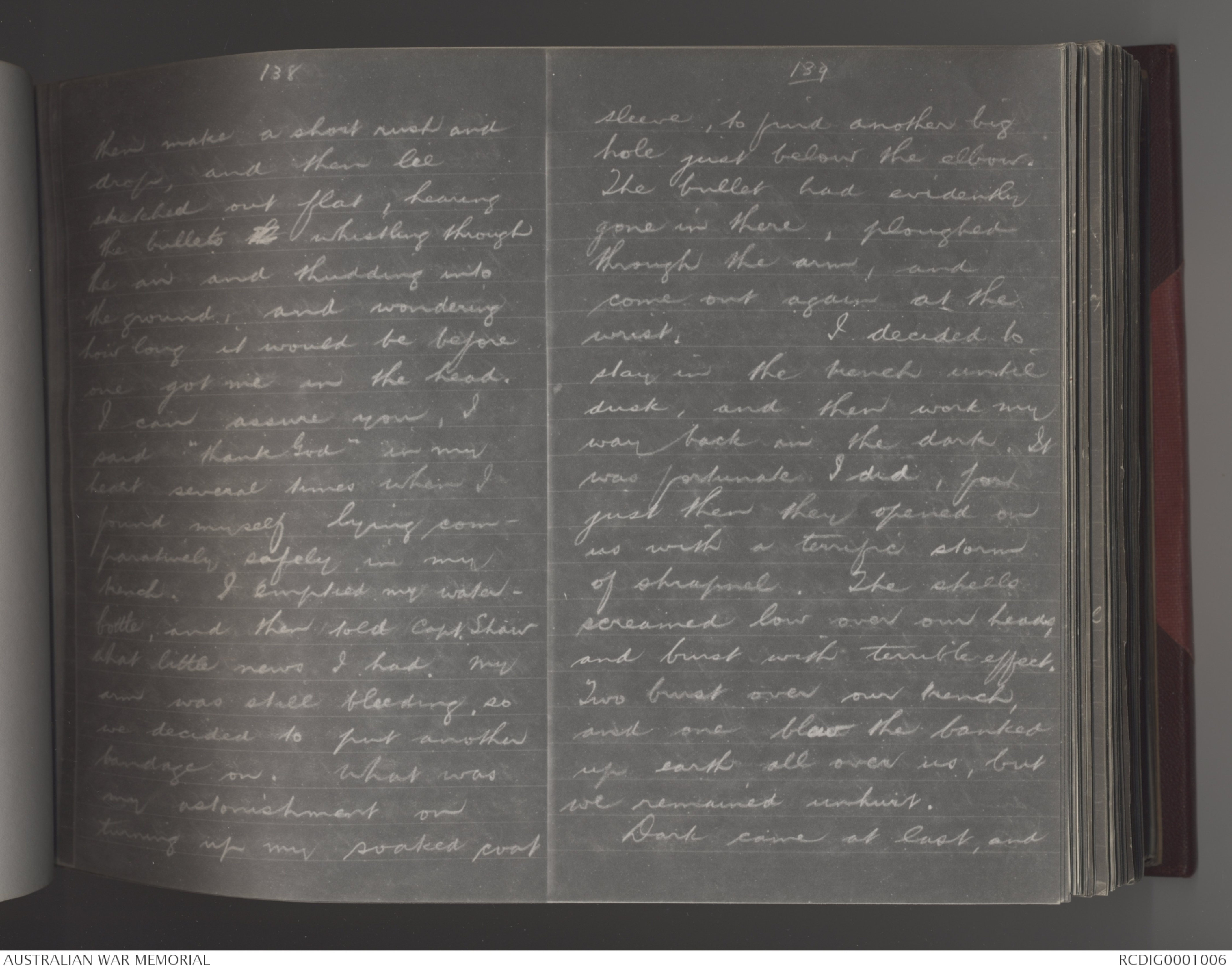

138

then make a short rush and

drop, and then let

stretched out flat, hearing

the bullets xx whistling through

the air and thudding into

the ground, and wondering

how long it would be before

one got me in the head.

I can assure you, I

said "thank God" in my

head several times when I

found myself lying comparatively

safely in my

trench. I emptied my waterbottle,

and then told Capt. Shaw

what little news I had. My

arm was still bleeding so

we decided to put another

bandage on. What was

my astonishment on

turning up my soaked coat

139

sleeve, to find another big

hole just below the elbow.

The bullet had evidently

gone in there, ploughed

through the arm, and

come out again at the

wrist. I decided to

stay in the trench until

dusk, and then work my

way back in the dark. It

was fortunate I did, for

just then they opened on

us with a terrific storm

of shrapnel. The shells

screamed low over our heads,

and burst with terrible effect.

Two burst over our trench,

and one blew the banked

up earth all over us, but

we remained unhurt.

Dark came at last, and

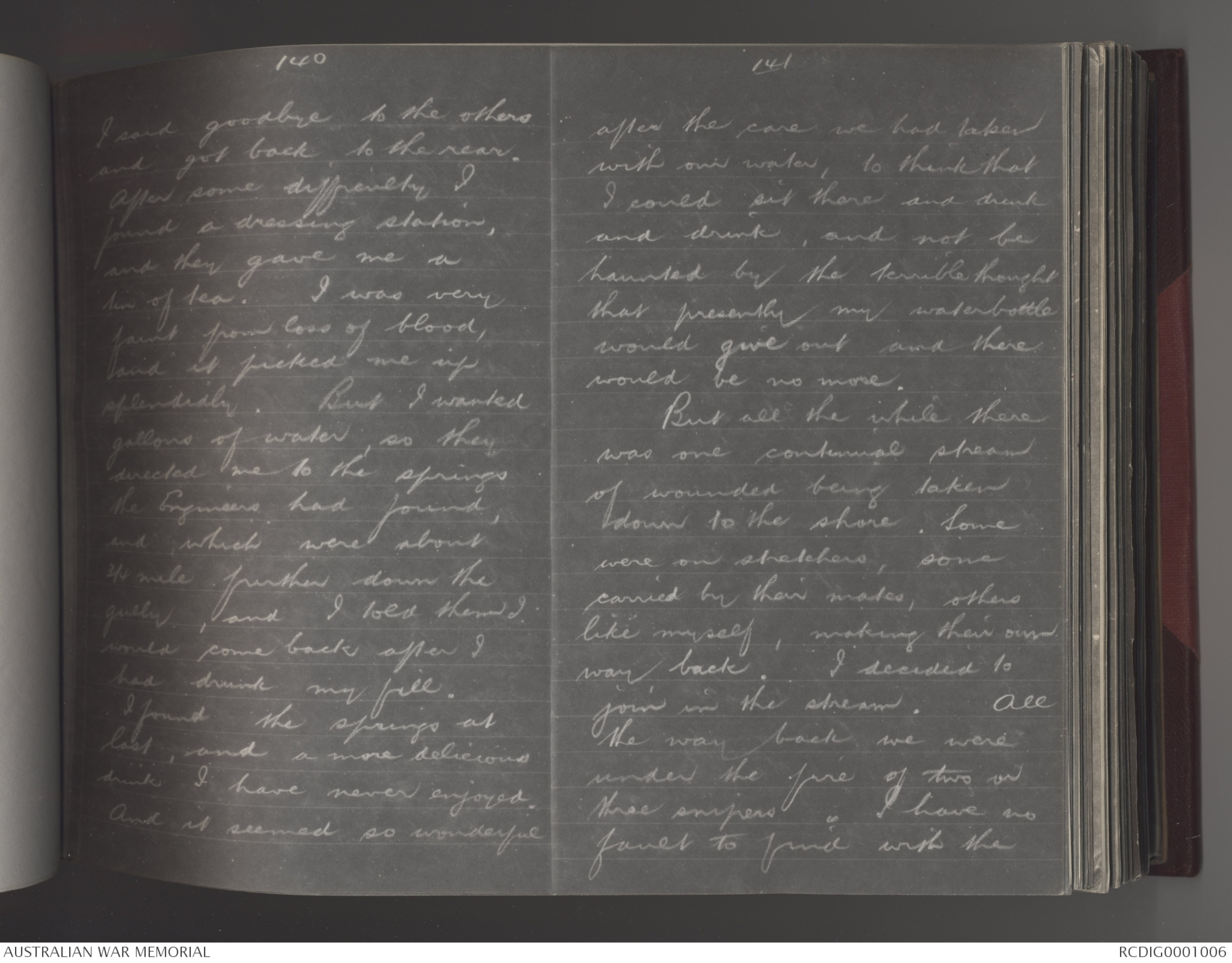

140

I said goodbye to the others

and got back to the rear.

After some difficulty I

found a dressing station,

and they gave me a

tin of tea. I was very

faint from loss of blood,

and it picked me up

splendidly. But I wanted

gallons of water, so they

directed me to the springs

the Engineers had found,

and which were about

3/4 mile further down the

gully, and I told them I

would come back after I

had drunk my fill.

I found the springs at

last, and a more delicious

drink I have never enjoyed.

And it seemed so wonderful

141

after the care we had taken

with our water, to think that

I could sit there and drink

and drink, and not be

haunted by the terrible thought

that presently my waterbottle

would give out and there

would be no more.

But all the while there

was one continual stream

of wounded being taken

down to the shore. Some

were on stretchers, some

carried their mates, others

like myself, making their own

way back. I decided to

join in the stream. All

the way back we were

under the fire of two or

three snipers . I have no

fault to find with the

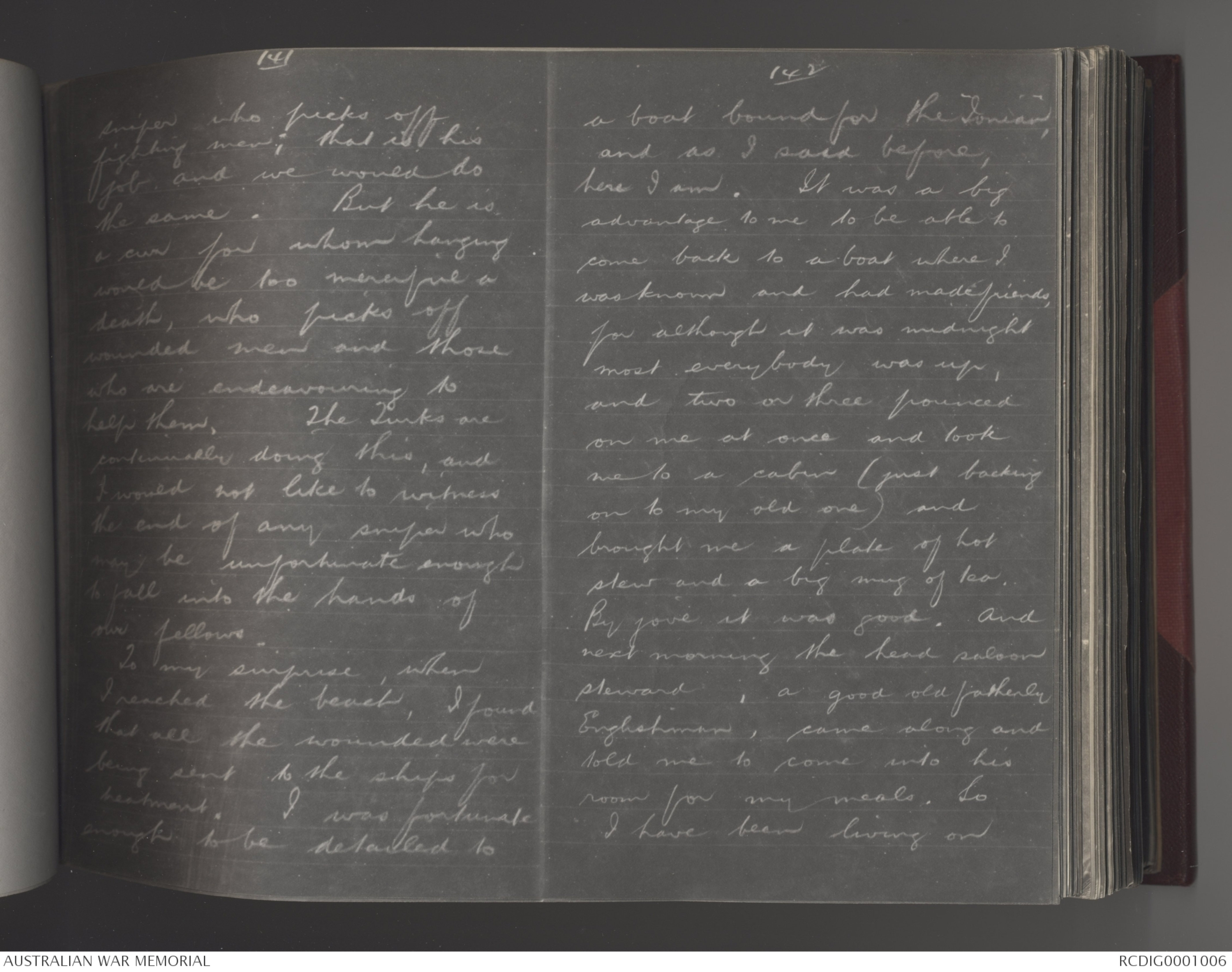

141

sniper who picks off

fighting men; that is his

job and would do

the same. But he is

a cur for whom hanging

would be too merciful a

death, who picks off

wounded men and those

who are endeavouring to

help them. The Turks are

continually doing this, and

I would not like to witness

the end of any sniper who

may be unfortunate enough

to fall into the hands of

our fellows.

To my surprise, when

I reached the beach, I found

that all the wounded were

being sent to the ships for

treatment. I was fortunate

enough to be detailed to

142

a boat bound for the "Ionian",

and as I said before,

here I am. It was a big

advantage to me to be able to

come back to a boat where I

was known and had made friends,

for although it was midnight

most everybody was up,

and two or three pounced

on me at once and took

me to a cabin (just backing

on to my old one) and

brought me a plate of hot

stew and a big mug of tea.

By jove it was good. And

next morning the head saloon

steward, a good old fatherly

Englishman, came along and

told me to come into his

room for my meals. So

I have been living on

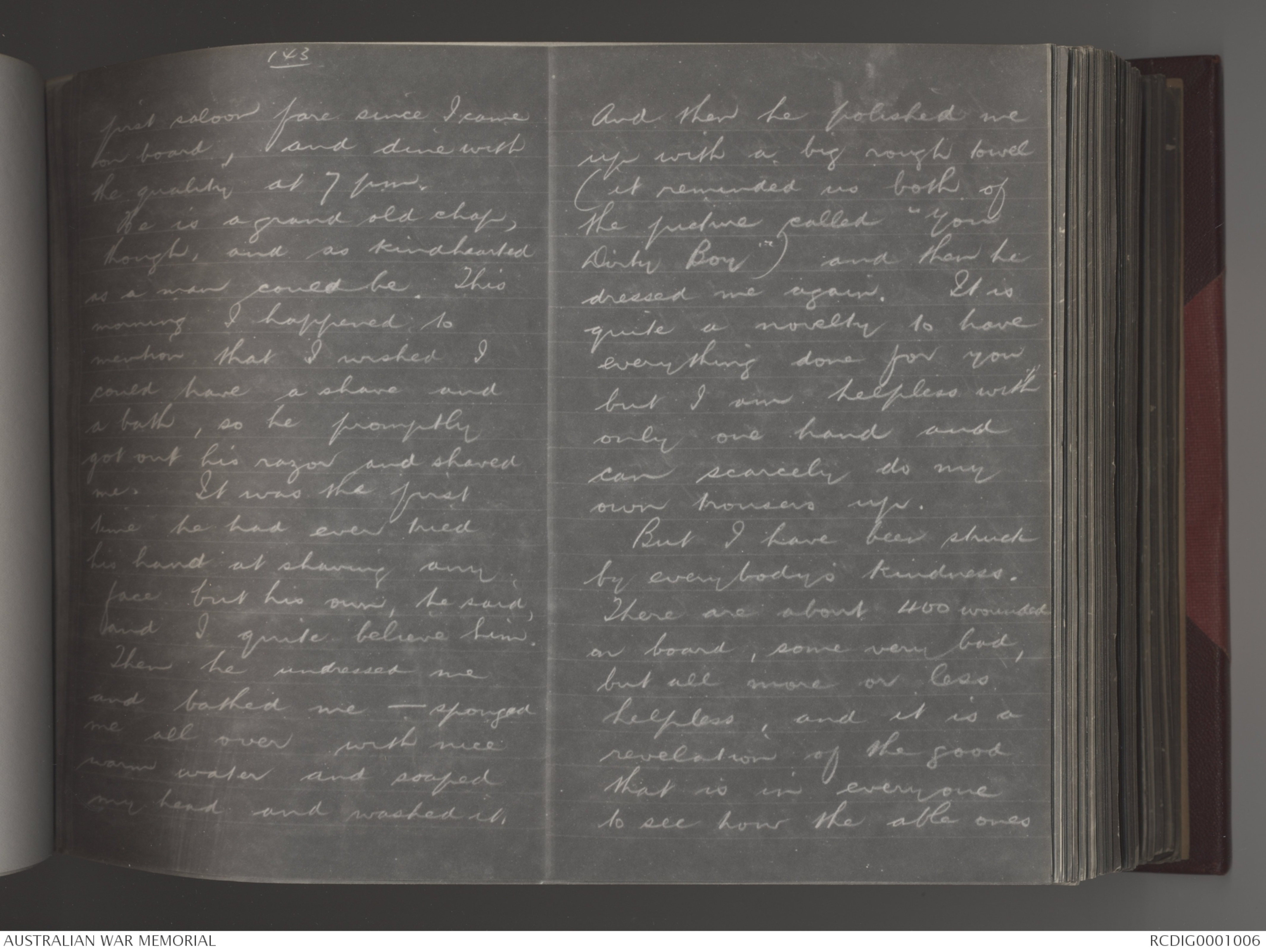

143

first saloon fare since I come

on board, and dine with

the quality at 7 p.m.

He is a grand old chap,

though, and as kindhearted

as a man could be. This

evening I happened to

mention that I wished I

could have a shave and

a bath, so he promptly

got out his razor and shaved

me. It was the first

time he had ever tried

his hand at shaving any

face but his own, he said,

and I quite believe him.

Then he undressed me

and bathed me - sponged

me all over with nice

warm water and soaped

my head and washed it.

And then he polished me

up with a big rough towel

(it reminded us both of

the picture called "You

Dirty Boy") and then he

dressed me again. It is

quite a novelty to have

everything done for you

but I am helpless with

only one hand and

can scarcely do my

own trousers up.

But I have been struck

by everybody's kindness.

There are about 400 wounded

on board, some very bad,

but all more or less

helpless, and it is a

revelation of the good

that is in everyone

to see how the able ones

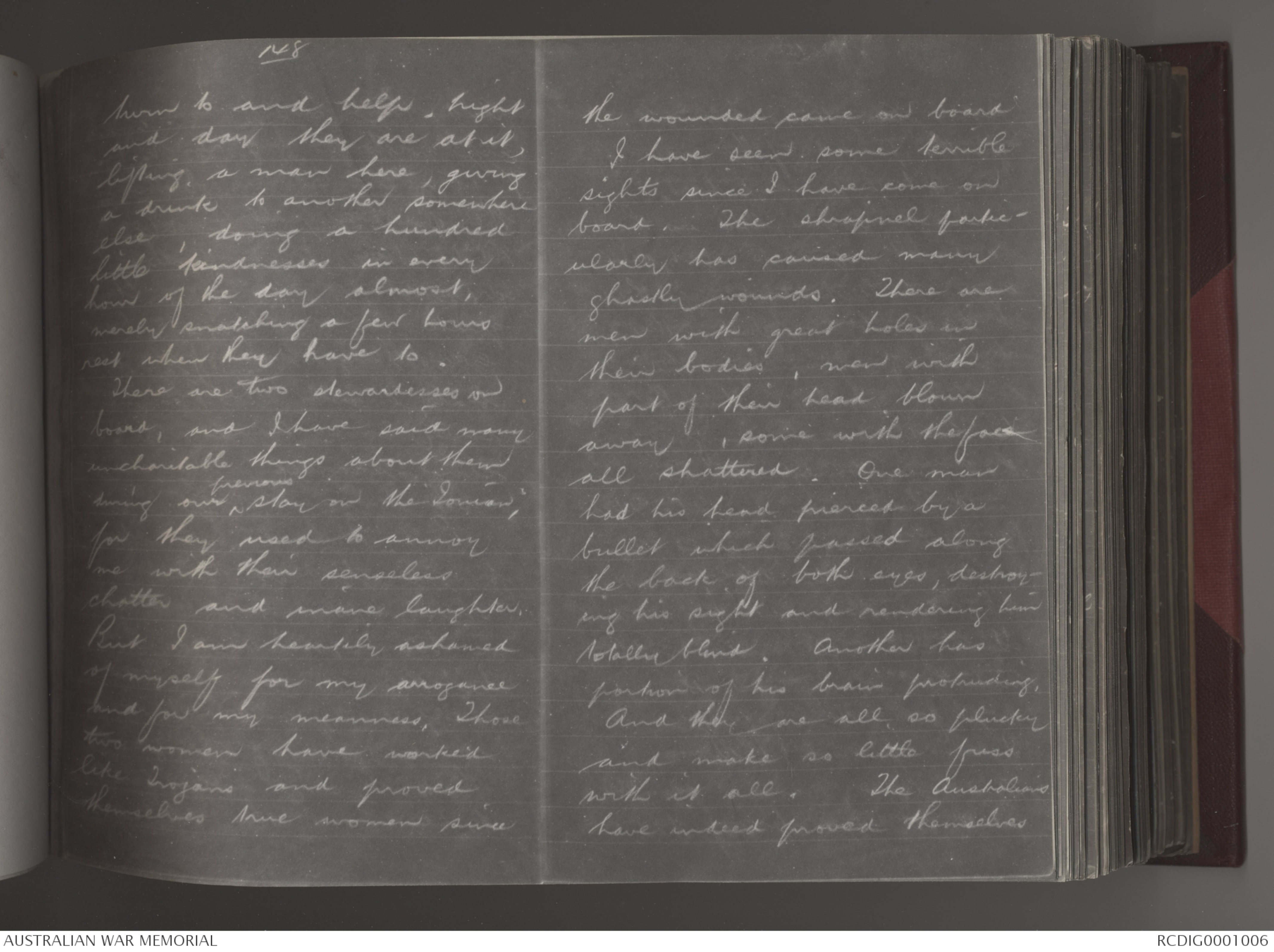

148

turn to and help. Night

and day they are at it,

lifting a man here, giving

a drink to another somewhere

else, doing a hundred

little kindnesses in every

hour of the day almost,

merely snatching a few hours

rest when they have to.

There are two stewardesses on

board, and I have said many

uncharitable things about them

during our ∧ previous stay on the "Ionian",

for they used to annoy

me with their senseless

chatter and inane laughter.

But I am heartily ashamed

of myself for my arrogance

and for my meanness. Those

two women have worked

like Trojans and proved

themselves true women since

the wounded came on board.

I have seen some terrible

sights since I have come on

board. The shrapnel particularly

has caused many

ghastly wounds. There are

men with great holes in

their bodies, men with

part of the head blown

away, some with the face

all shattered. One man

had his head pierced by a

bullet which passed along

the back of both eyes, destroying

his sight and rendering him

totally blind. Another has

portion of his brain protruding.

And they are all, so plucky

and make so little fuss

with it all. The Australians

have indeed proved themselves

Loretta Corbett

Loretta CorbettThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.