General, Sir John Monash, Personal Files Book 22, 10 April - 1 June 1919- Part 6

[*See OPF No 48

9/5/19

HIT

9/5/19*]

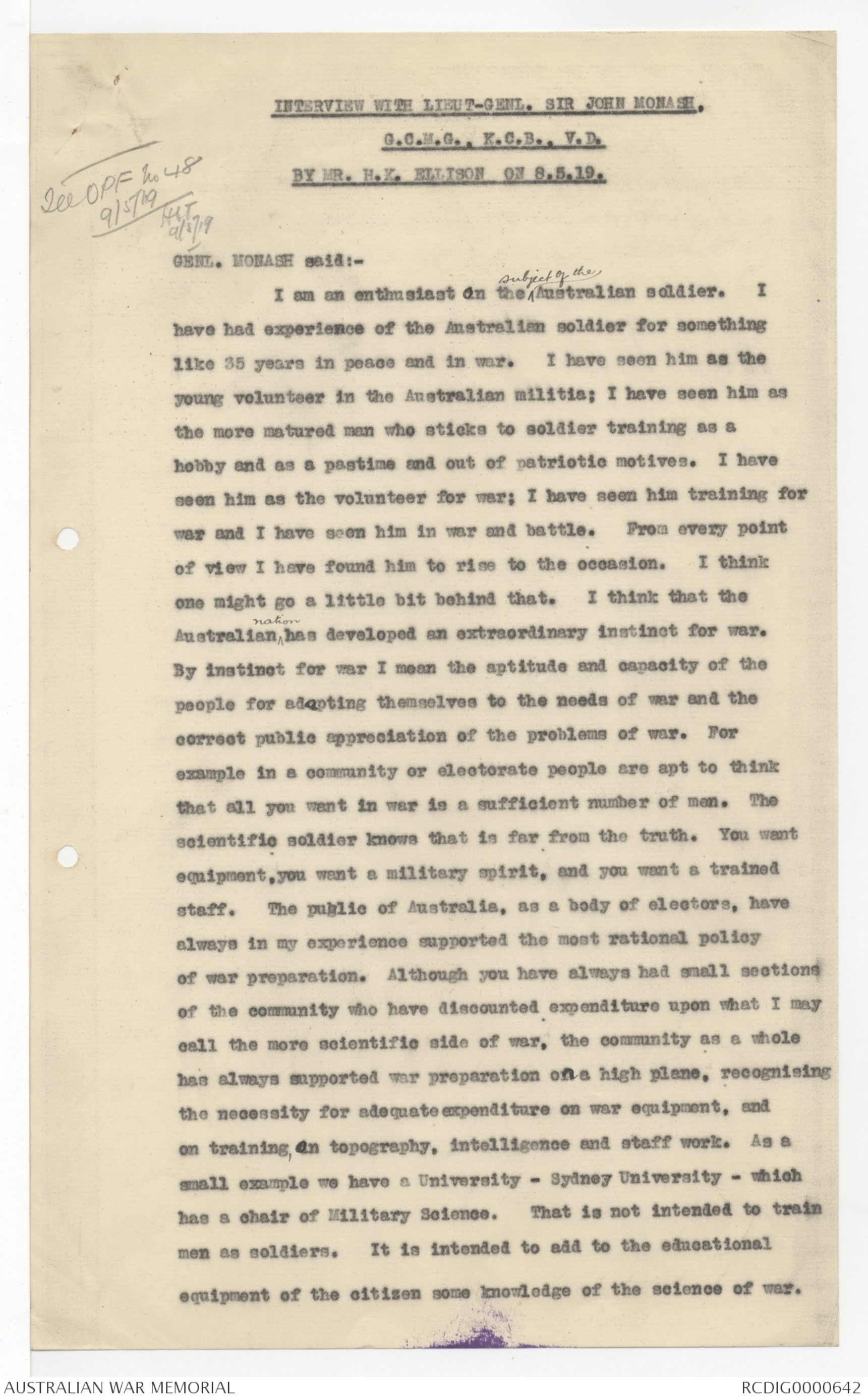

INTERVIEW WITH LIEUT-GENL. SIR JOHN MONASH.

G.C.M.G., K.C.B., V.D.

BY MR. H.K. ELLISON ON 8.5.19.

GENL. MONASH said:-

I am an enthusiast on the ^subject of the Australian soldier. I

have had experience of the Australian soldier for something

like 35 years in peace and in war. I have seen him as the

young volunteer in the Australian militia; I have seen him as

the more matured man who sticks to soldier training as a

hobby and as a pastime and out of patriotic motives. I have

seen him as the volunteer for war; I have seen him training for

war and I have seen him in war and battle. From every point

of view I have found him to rise to the occasion. I think

one might go a little bit behind that. I think that the

Australian ^nation has developed an extraordinary instinct for war.

By instinct for war I mean the aptitude and capacity of the

people for adapting themselves to the needs of war and the

correct public appreciation of the problems of war. For

example in a community or electorate people are apt to think

that all you want in war is a sufficient number of men. The

scientific soldier knows that is far from the truth. You want

equipment, you want a military spirit, and you want a trained

staff. The public of Australia, as a body of electors, have

always in my experience supported the most rational policy

of war preparation. Although you have always had small sections

of the community who have discounted expenditure upon what I may

call the more scientific side of war, the community as a whole

has always supported war preparation one high plane, recognising

the necessity for adequate expenditure on war equipment, and

on training on topography, intelligence and staff work. As a

small example we have a University - Sydney University - which

has a chair of Military Science. That is not intended to train

men as soldiers. It is intended to add to the educational

equipment of the citizen some knowledge of the science of war.

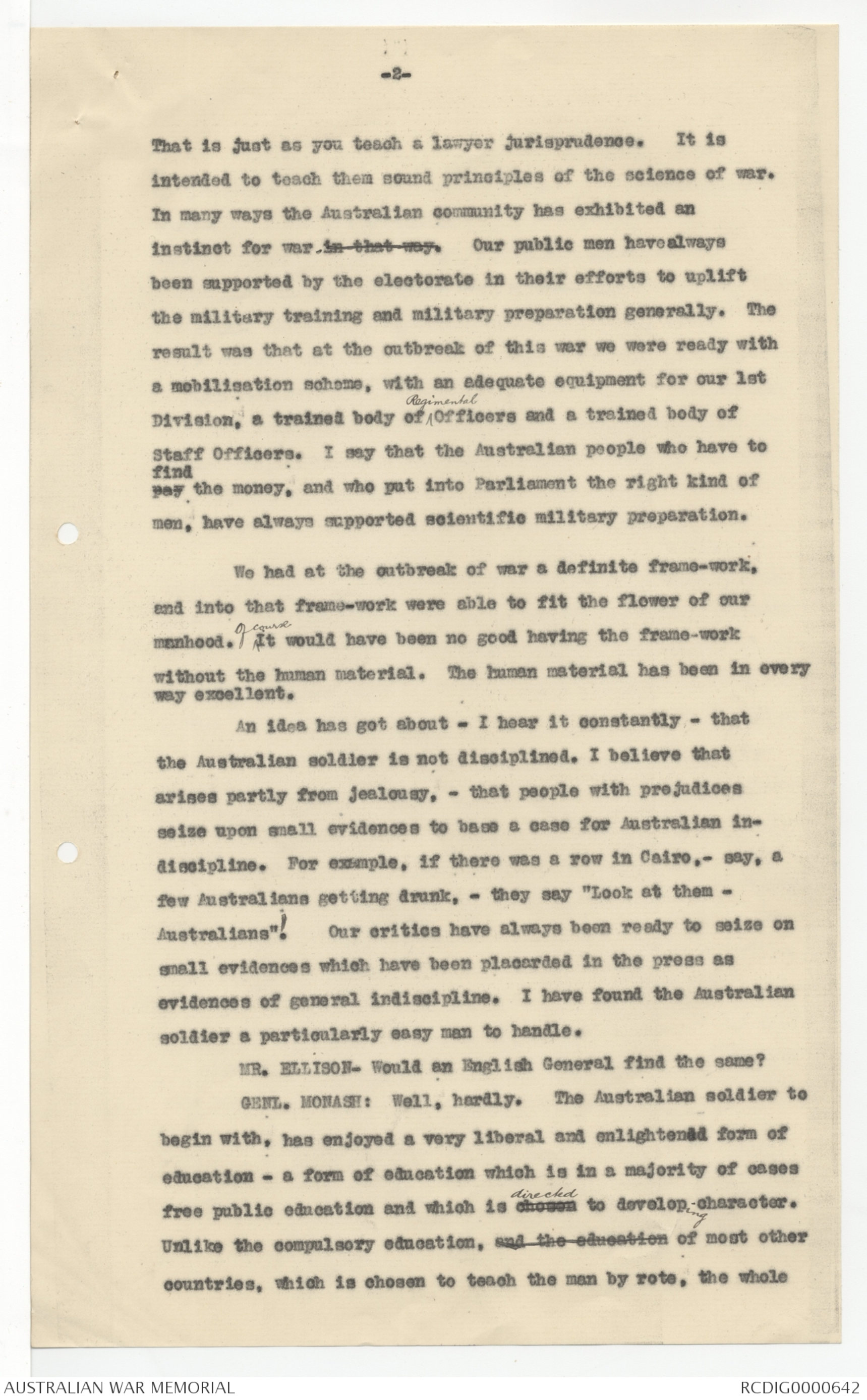

-2-

That is just es you teach a lawyer jurisprudence. It is

intended to teach them sound principles of the science of war.

In many ways the Australian community has exhibited as

instinct for war. in that way. Our public men have always

been supported by the electorate in their efforts to uplift

the military training and military preparation generally. The

result was that at the outbreak of this war we were ready with

a mobilisation scheme, with an adequate equipment for our lst

Division, a trained body of ∧ Regimental Officers end a trained body of

staff Officers. I say that the Australian people who have to

find pay the money, and who put into Parliament the right kind of

men, have always supported scientific military preparation.

We had at the outbreak of war a definite frame-work

and into that frame-work were able to fit the flower of our

manhood. ∧Of course it would have been no good having the frame-work

without the human material. The human material has been in every

way excellent.

An idea has got about - I hear it constantly - that

the Australian soldier is not disciplined. I believe that

arises partly from jealousy, - that people with prejudices

seize upon small evidences to base a case for Australian indiscipline.

For example, if there was a row in Cairo, - say, a

few Australians getting drunk, - they say "Look et them -

Australians"! Our critics have always been ready to seize on

small evidences which have been placarded in the press as

evidences of general indiscipline. I have found the Australian

soldier a particularly easy man to handle.

MR. ELLISON- Would an English General find the same?

GENL. MONASH: Well, hardly. The Australian soldier to

begin with, has enjoyed a very liberal and enlightened form of

education - a form of education which is in a majority of cases

free public education and which is chosen directed to developing character.

Unlike the compulsory education, and the education of most other

countries, which is chosen to teach the man by rote, the whole

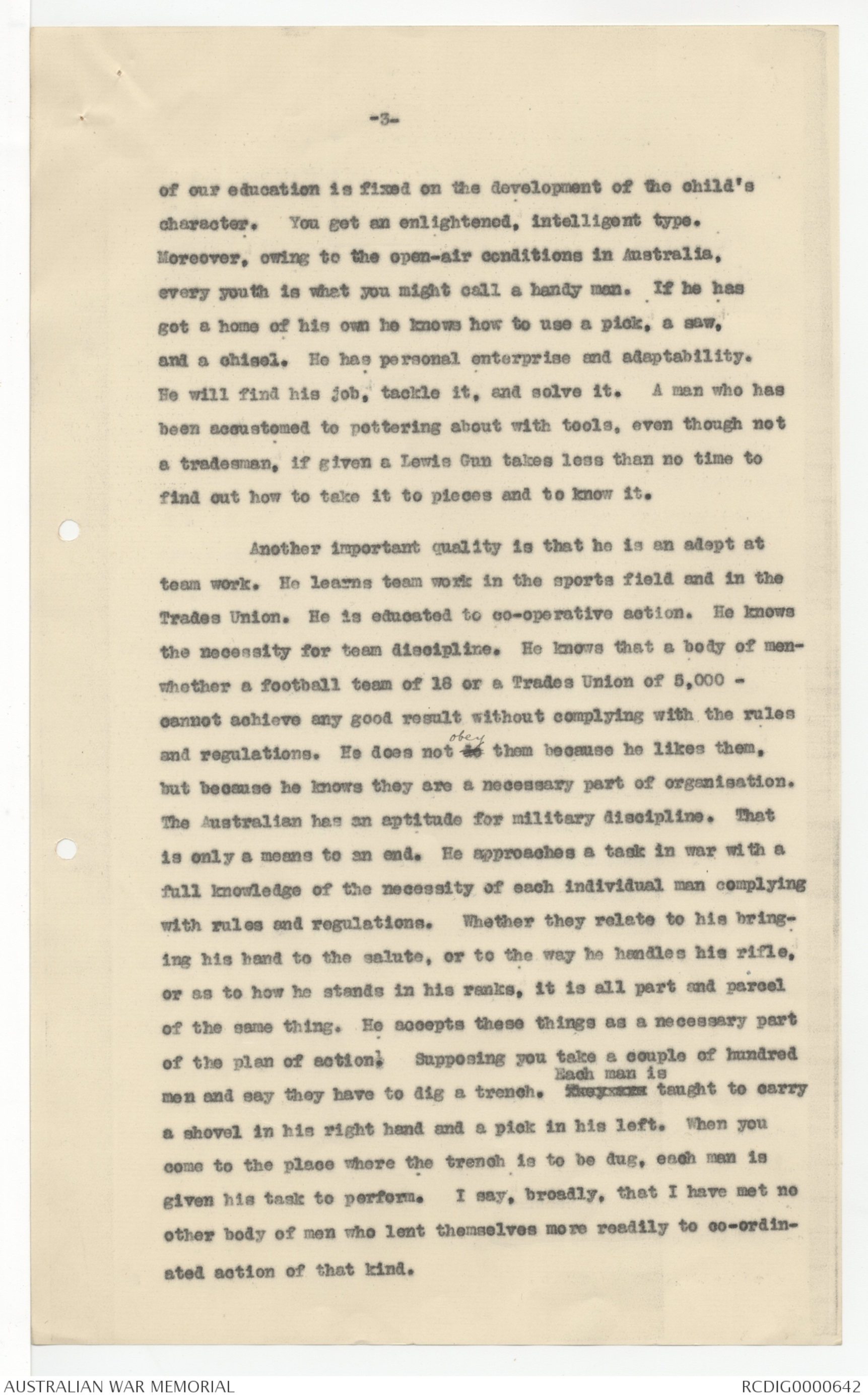

-3-

of our education is fixed on the development of the child's

character. You get an enlightened, intelligent type.

Moreover, owing to the open-air conditions in Australia,

every youth is what you might call a handy man. If he has

got a home of his own he knows how to use a pick, a saw,

and a chisel. He has personal enterprise and adaptability.

He will find his job, tackle it, and solve it. A man who has

been accustomed to pottering about with tools, even though not

a tradesman, if given a Lewis Gun takes less than no time to

find out how to take it to pieces and to know it.

Another important quality is that he is an adept at

team work. He learns team work in the sports field and in the

Trades Union. He is educated to co-operative action. He knows

the necessity for team discipline. He knows that a body of men-

whether a football team of l8 or a Trades Union of 5,000 -

cannot achieve any good result without complying with the rules

and regulations. He does not do obey them because he likes them,

but because he knows they are a necessary part of organisation.

The Australian has an aptitude for military discipline. That

is only a means to an end. He approaches a task in war with a

full knowledge of the necessity of each individual man complying

with rules and regulations. Whether they relate to his bringing

his hand to the salute, or to the way he handles his rifle,

or as to how he stands in his ranks, it is all part and parcel

of the same thing. He accepts these things as a necessary part

of the plan of action. Supposing you take a couple of hundred

men and say they have to dig a trench. They xxx Each man is taught to carry

a shovel in his right hand and a pick in his left. When you

come to the place where the trench is to be dug, each man is

given his task to perform. I say, broadly, that I have met no

other body of men who lent themselves more readily to co-ordinated

action of that kind.

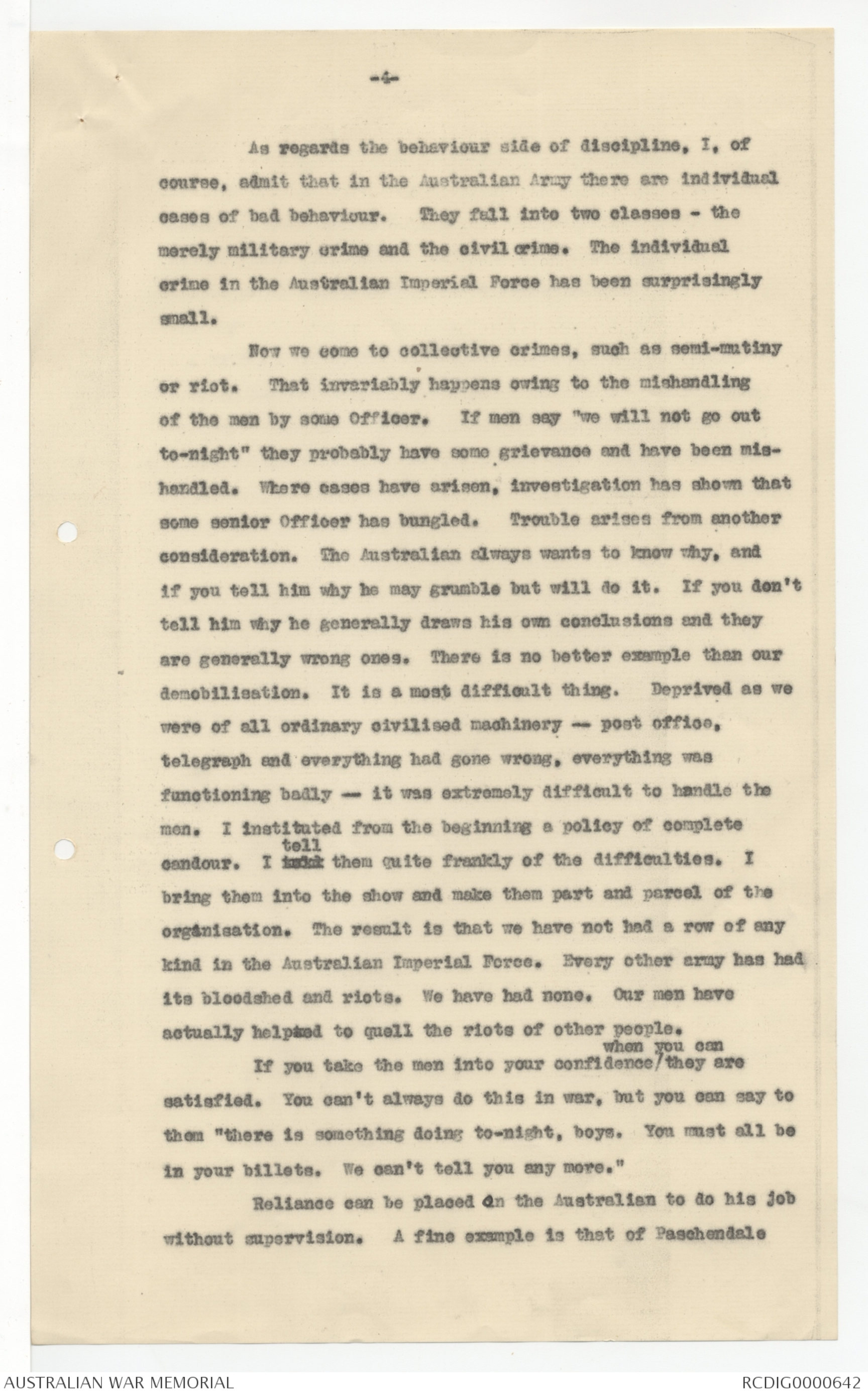

-4-

As regards the behaviour side of discipline, I, of

course, admit that in the Australian Army there are individual

cases of bad behaviour. They fall into two classes - the

merely military crime and the civil crime. The individual

crime in the Australian Imperial Force has been surprisingly

small.

Now we come to collective crimes, such as semi-mutiny

or riot. That invariably happens owing to the mishandling

of the men by some Officer. If men say "we will not go out

to-night" they probably have some grievance and have been mishandled.

Where cases have arisen, investigation has shown that

some senior Officer has bungled. Trouble arises from another

consideration. The Australian always wants to know why, and

if you tell him why be may grumble but will do it. If you don't

tell him why he generally draws his own conclusions and they

are generally wrong ones. There is no better example than our

demobilisation. It is a most difficult thing. Deprived as we

were of all ordinary civilised machinery - post office,

telegraph and everything had gone wrong, everything was

functioning badly - it was extremely difficult to handle the

men. I instituted from the beginning e policy of complete

candour. I told tell them quite frankly of the difficulties. I

bring them into the show and make them part and parcel of the

organisation. The result is that we have not had a row of any

kind in the Australian Imperial Force. Every other army has had

its bloodshed and riots. We have had none. Our men have

actually helped to quell the riots of other people.

If you take the men into your confidence ∧when you can they are

satisfied. You can't always do this in war, but you can say to

them "there is something doing to-night, boys. You must all be

in your billets. We can't tell you any more."

Reliance can be placed on the Australian to do his job

without supervision. A fine example is that of Paschendale

-5-

in 1917, where the conditions were the most horrible that

any army had to face - mud, and slush, and rain, and every

kind of stress and shellfire. The problem of supplying

the guns with ammunition was most difficult. The only way

to get it up was to give a man a couple of mules and panniers

end say "Your job is to carry ammunition from this dump to

the guns". You could not supervise his work ∧but you could

rely on him to carry on until he or his mules dropped dead.

Again, if you gave certain men the tucker for the rest of

their Company and told them "Here you are: here is the tucker;

take it to the men", they would rather die than not take it to

their comrades, even though they did not know where they were,

and had to search for their position.

RELATIONS BETWEEN AUSTRALIANS AND ENGLISH: I have a very

high opinion of the British effort, and a very high opinion

of some very fine Units- the British Cavalry, the Guards,

and the 29th and 51st Divisions. I also have a high opinion

of the quiet way in which the United Kingdom is returning to

peace conditions. I do believe it is going remarkably well.

From the point of view of the man in the ranks,

his personal experience of the British soldier by actual

contact in battle has been unsatisfactory. He takes a narrow

view. He only sees what is in front of his eyes. It has been

our bad luck to have had rotten troops with us. They have let

us down. An Australian never forgives being let down. A bad

case was that of Etinehem Spur which they failed to take, and

a mile of flank was left exposed. It did not take many hours

for that sort of thing to be talked about throughout the

whole five Divisions. That creates bad feeling.

From an industrial point of view, our men think

very badly of the British artisan, particularly his attitude

towards industrial problems. I am sorry to say that I think

the opinion of the A.I.F. of the Mother Country has fallen

instead of risen.

-6-

I do not think that feeling is shared by senior officers or

intellectual men. I think the Australian will go back to

Australia prouder of his own country than ever, both in the

abstract and in comparison with other countries.

We Australians think that we are not only a nation,

but a very formidable nation.

As regards the nationhood, it did not take many weeks

of war to dissipate anything in the nature of Interstate

jealousies. While we started from Australia saying "I am a

Victorian" or "I am a Tasmanian" that rapidly disappeared. We

rapidly became 'Aussies". It invariably happened that when

a person asked an Australian where he came from (meaning what

part of Australia) he would reply "From Australia".

I hope that the A.I.F. will be a very powerful

spiritual momentum in Australia in every way.

Australia has made very big sacrifices. Her casualties

comprised 60,000 dead and 200,000 wounded. What she will get out

of the was is e sense of nationhood. She will get a very greatly

enhanced confidence in herself, and will get a the spiritual momentum

given by the enlargement of view of something like 300,000 men

who have learnt to know the world and have gone through a wonderful

experience of life. The tradition of the A.l.F. is going to

be a wonderful thing. I am inclined to think that there will be

grow up a sort of schism of the men who did, and the men who

didn't. I think the A.I.F. will hang together, and will combine

for the achievement of a higher national efficiency. It is the

case of the man who knows, and the man who doesn't. Just imagine

a man on a farm who hasn't been over here arguing about the conditions

in France or England!! He knows nothing compared with the

man who has been and seen. They ∧latter will become a class by themselves.

There are a great many Officers who have decided enjoyed

authority and the pleasure of being an autocrat who will not want

-7-

to go back to civil private life. Many will want to take part in

public affairs. They will get the support of their own men.

There is nothing calculated to cement allegiance so much as

successful leadership. If a man can lead troops successfully

in war end make them win battles, no man can stand up against

him.

I think that Imperial training need only be confined

to the training of staffs. I do not think any good purpose

is to be served in sending actual personnel – actual troops -

to other Dominions, for after all a Trench Mortar is a Trench

Mortar and a Lewis Gun is a Lewis Gun everywhere. We mast continue

to have interchanges among senior Officers and Staff

Officers, not only with England but other Dominions. We will

always have staff Officers at Military Colleges in England and

India.

I want to try to improve the ∧military education of the public

of Australia. If you have money to spend do not spend it all

on teaching men how to handle a rifle; spend ∧most of it on buying

ammunition and equipment and in training staff Officers. You

can make a soldier quicker then you can make a gun.

As an example of what can be done with the right kind

of human material in creating a formidable fighting unit, I

should like to instance the example of the 3rd Australian

Division. This Division was raised in Australia in the early

part of 1916 at a time when Australia had already sent abroad

every scrap of military equipment in its possession. The

20,000 men of this Division therefore arrived in England during

July and August, 1916, absolutely devoid of every kind of

military equipment except the uniforms in which they stood. The

great majority of the men had never handled a rifle; none of them

had ever even seen a Lewis Gun, or a Vickers Machine Gun, or a

Trench Mortar, or an 18-pounder gun, or a 4.5 inch Howitzer.

Most of the troops had never seen their commanders.

-8-

None of them had ever met together before in numbers greater

than a Battalion. This conglomerate mass of individuals

arrived in England at the rate of about 3,000 a week during

July and August. In the early part of September the War

Office began to dole out training equipment on a very inadequate

scale, never exceeding 10% of requirements. This

included horses, vehicles, motor transport and the like.

Serious work of organisation and training could not commence

on anything like an adequate scale until the first week in

October, 1916. In spite of all these difficulties this

Division was actually carrying out successful fighting against

the enemy by the last week of November, 1916. This was the

Division which not long afterwards took such a brilliant part

in the capture of Messines.

That is a proof of what I say that the men man is the

last thing that you need care about in war. If I had not been

able to get the Lewis Guns &c and the trained instructors those

20,000 men would have been useless. They would never have

been an army. Having the Guns and the instructors the men were

the last thing ∧in order of importance.

In regard to demobilisation the men had to be kept

contented. The psychology had to be watched. It was a

psychological problem. Seeing that it was inevitable that

more than 2/3rds. of the total number of troops would remain

in Europe for more then three to six months I encouraged them to

apply for some form of civil training and secured from my

Government authority to spend a considerable amount on pay and

subsistence. We now have a very large number of men in positions

from the student in the University down to the artisan in the

factory or workshop. It has ∧had a wonderful effect. It has turned

their thoughts from war to peace. It has given them something

to think of in regard to what they will be when they get home,

end as to how they will improve their positions. It has a

-9-

general tendency to uplift them. Although the material

results are not very big, yet the main thing is the

psychological effect upon the men. They had all turned their

thoughts to the future. The men are put on the very best

possible terms. They are getting their Military pay, and

are allowed to pocket any earnings they may receive. The

Government has got to pay them, ∧whether or no and they might as well be

employing themselves usefully instead of having to stay in

the camps. The positions cover the whole field of industry

and the professions. The men may be divided into two classes¬

those men who are at a definite curriculum for definite set

periods, and those men who are merely carrying on until their

ship is ready to sail. The latter kind are called up several back to camp

weeks before their ship is due to sail.

As regards Demobilisation progress, we will have

reached the half-way house in our programme in a week from

now. The end of the year should clean everything up.

Up to date, only 1200 applications for discharge

elsewhere than in Australia have been received and granted,

and then this number includes a number of cases of men of

independent means who received their discharges here in order

to enable them to proceed home via America and other routes,

and undergo training in foreign countries.

The total discharges, ∧will eventually amount to a little more than

one per cent of the whole Australian Imperial Force.

Sam scott

Sam scottThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.