Papers written by Hodgkin, Ernest P. (Doctor, b.1908 - d.1998) - Part 10

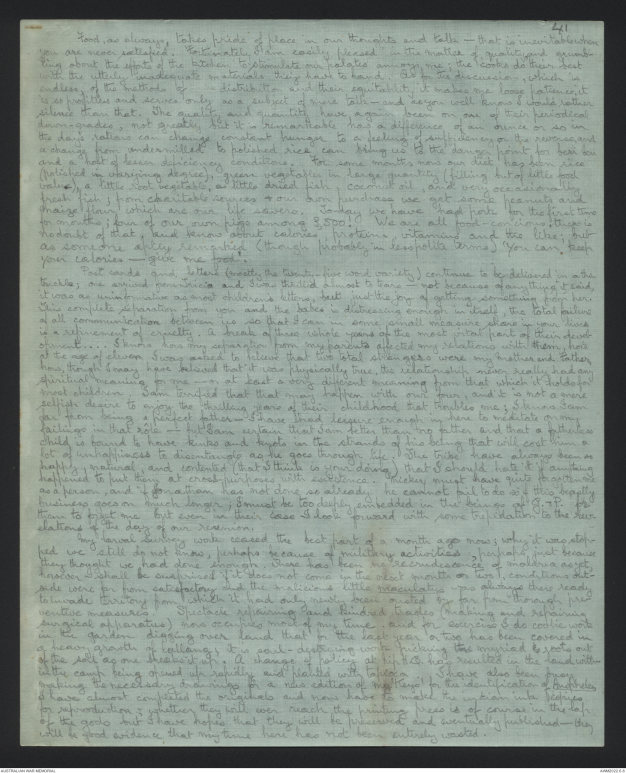

41

Food, as always, takes pride of place in our thoughts and talk - that is inevitable when

you are never satisfied. Fortunately I am easily pleased in the matter of quality and grumbling

about the efforts of the kitchen to stimulate our palates' annoy me ; the cooks do their best

with the utterly inadequate materials they have to hand. As for the discussion, which is

endless, of the methods of distribution and their equitability it makes me loose patience, it

is so profitless and serves only as a subject of more talk - and as you well know I would rather

silence than that. The quality and quantity have again been on one of their periodical

down-grades, not greatly but it is remarkable how a difference of an ounce or so in

the day's rations can change constant hunger to a feeling of sufficiency or the nausea, and

a change from undermilled to polished rice can bring us to the danger point for beri beri

and a host of lesser deficiency conditions. For some months now our diet has been rice

(polished in varying degree), green vegetables in large quantity (filling but of little food

value), a little root vegetable, a little dried fish, coconut oil, and very occasionally

fresh fish, from charitable sources & our own purchase we get some peanuts and

maize flour which are our life savers. Today we have had pork for the first time

for months; four of our own pigs among 3,500! We are all food-conscious, there is

no doubt of that, and know about calories, proteins, vitamins and the like; but

as someone aptly remarked (though probably in less polite terms) 'You can keep

your calories - give me food'.

Post cards and letters (mostly the twenty-five word variety) continued to be delivered in a the

trickle, one arrived from Tricia and I was thrilled almost to tears - not because of anything it said,

it was as uninformative as most children's letters, but just the joy of getting something from her.

This complete separation from you and the babes is distressing enough in itself, the total failure

of all communication between us so that I can in some small measure share in your lives

is a refinement of cruelty. A break of these whole years of the most vital point of their development....

I know how my separation from my parents affected my relations with them, how

at the age of eleven, I was asked to believe that two total strangers were my Mother and Father,

how, though I may have believed that it was physically true, the relationship never really had any

spiritual meaning for me - or at least a very different meaning from that which it holds for

most children. I am terrified that that may happen with our four, and it is not a mere

selfish desire to enjoy the thrilling years of their childhood that troubles me; I know I am

far from being a perfect father - I have had leisure enough in here to meditate on my

failings in that ro^le - but I am certain that I am better than no father and that a fatherless

child is bound to have kinks and knots in the strands of his being that will cost him a

lot of unhappiness to disentangle as he goes through life. The tribe have always been a

happy, natural, and contented (that I think is your doing) that I should hate it if anything

happened to put them at cross-purposes with existence. Mickey must have quite forgotten me

as a person, and if Jonathon has not done so already, he cannot fail to do so if this beastly

business goes on much longer; I must be too deeply embedded in the beings of G.-P. for

them to forget me but even in their case I look forward with some trepidation to the

revelations of the day of our reunion.

My larval survey work ceased the best part of a month ago now; why it was stopped

we still do not know, perhaps because of military activities, perhaps just because

they thought we had done enough. There has been no recrudesence of malaria as yet,

however I shall be surprised if it does not come in the next month or two, conditions

outside were far from satisfactory and the malicious little maculatus was always there ready

to invade territory from which it had only newly been ousted by far from thorough

preventative measures. Spectacle reframing and kindred trades (making and repairing

surgical apparatus) now occupies most of my time and for exercise I do coolie work

in the garden digging over land that for the last year or two has been covered in

a heavy growth of lallang, it is soul-destroying work picking the myriad of roots out

of the soil as one breaks it up. A change of policy at nip H.Q. has resulted in the land within

the camp being opened up rapidly and planted with tapioca. I have also been busy

making the necessary drawings of a new edition of my 'Keys' for the identification of [?]

I have almost completed the originals and now have to make the [interim] into copies

for reproduction; whether they will ever reach the printing press is of course in the lap

of the gods but I have hopes that they will be preserved and eventually published - they

will be good evidence that my time here has not been entirely wasted.

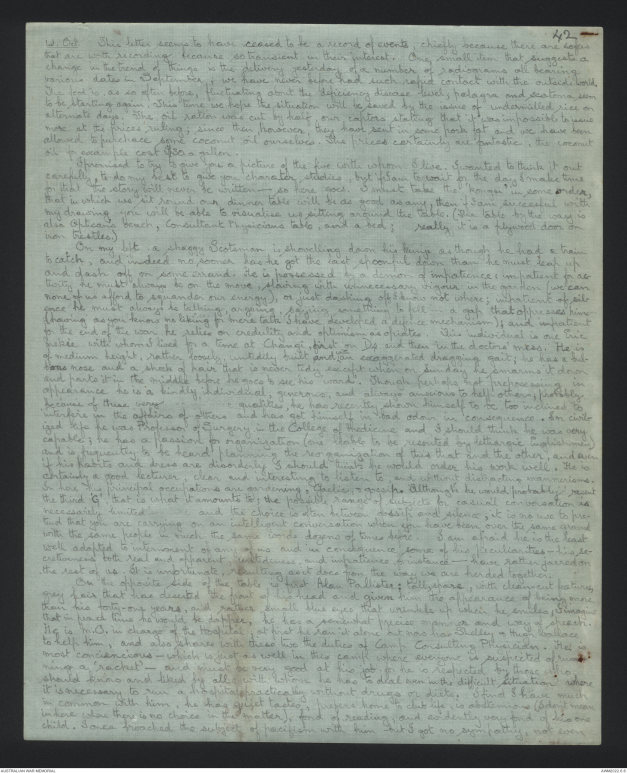

42

1st Oct. This letter seems to have ceased to be a record of events, chiefly because there are heaps

that are worth recording because so transient in their interest. One, small item that suggests a

change in the trend of things is the delivery yesterday of a number of radiograms all bearing

various dates in September, we have never before had such rapid contact with the outside world.

This led to, as so often before, fluctuating about the deficiency disease level, pelagra and scotoma, seem

to be starting again. This time we hope the situation will be saved by the issue of undermilled rice on

alternate days. The oil ration was cut by half, our captors stating that it was impossible to issue

more at the prices ruling; since then, however, they have sent in some pork fat and we have been

allowed to purchase some coconut oil ourselves. The prices certainly are fantastic, the coconut

oil for example cost $30 a gallon.

I promised to try to give you a picture of the five with whom I live. I wanted to think it out

carefully, to do my best to give you character studies, but if I am to wait for the day I make time

for that the story will never be written - so here goes. I must take the 'Konji' in some order,

that in which we sit round our dinner table will be as good as any, then if I am successful with

my drawing you will be able to visualise me sitting around the table. (The table by the way is

also Opticians bench, Consultant Physicians table, and a bed; really it is a plywood door on

iron trestles.)

On my shift a shaggy Scotsman is shovelling down his kenji as though he had a train

to catch, and indeed no sooner has he got the last spoonful down than he must leap up

and dash off on some errand. He is possessed by a demon of impatience & impatient for authority

he must always be on the move, moving with unnecessary vigour in the garden (we can

none of us afford to squander our energy), or just dashing off I know not where; impatient of silence

he must always be talking, arguing, saying something to fill a gap that oppresses him

(having as you know no liking for mere talk I have developed a defence mechanism); and impatient

for the end of the war he relies on credulity and optimism as opiates. This individual is one Eric

Mekie with whom I lived for a time at Changi, first on D4 and then in the doctors mess. He is

of medium height, rather loosely, untidily built and ^with an exaggerated dragging gait; he has a bulbous

nose and a shock of hair that is never tidy except when on Sunday he smarms it down

and parts it in the middle before he goes to see his "Grand". Though perhaps not prepossessing in

appearance he is a kindly individual, generous and always anxious to help others, probably

because of these very [[?]] qualities, he has recently shown himself to be too inclined to

interfere in the affairs of others and has got himself in bad odour in consequence. In civilised

life he was Professor of Surgery in the College of Medicine and I should think he was very

capable; he has a passion for organization (one liable to be resented by lethargic Englishmen)

and is frequently to be heard planning the reorganization of this that and the other, and even

if his habits and dress are disorderly I should think that he would order his work well. He is

certainly a good lecturer, clean and interesting to listen to, and without distracting mannerisms.

In fact his principal preoccupations are gardening, Gaelic & gossip. Although he would probably resent

the last 'G' that is what it amounts to the possible range of subjects for casual conversation is

necessarily limited [[?]] and the choice is often between gossip and silence, it is no use to pretend

that you are carrying on an intelligent conversation when you have been over the same ground

with the same people in much the same words dozens of times before. I am afraid he is the least

well adapted to internment of any of us and in consequence some of his peculiarities - his secretiveness

both real and apparent, untidiness and impatience, for instance - have rather jarred on

the rest of us. It is unfortunate, resulting as it does from the way we are herded together.

On the opposite side of the table is first Alan Pallister: tall, spare, with clean cut features,

grey hair that has deserted the front of his head and given him the appearance of being more

than his forty-one years, and rather small blue eyes that wrinkle up when he smiles, [[?]]

that in peace time he would be dapper, he has a somewhat precise manner and way of speech.

He is M.O in charge of the Hospital, at first he ran it alone but now has Shelley & Hugh Wallace

to help him, and also shares with these two the duties of Camp Consulting Physician. He is

most conscientious - which is just as well in this camp where everyone is suspected of running

a 'racket' - and must be very good at his job for he is respected by those who

it is necessary to run a hospital practically without drugs or diets. I find I have much

in common with him, he has quiet tastes, prefers home to club life, is abstemious (I don't mean

in here where there is no choice in the matter) , fond of reading, and evidently very fond of his one

child. I once broached the subject of pacifism with him but I got no sympathy, not even

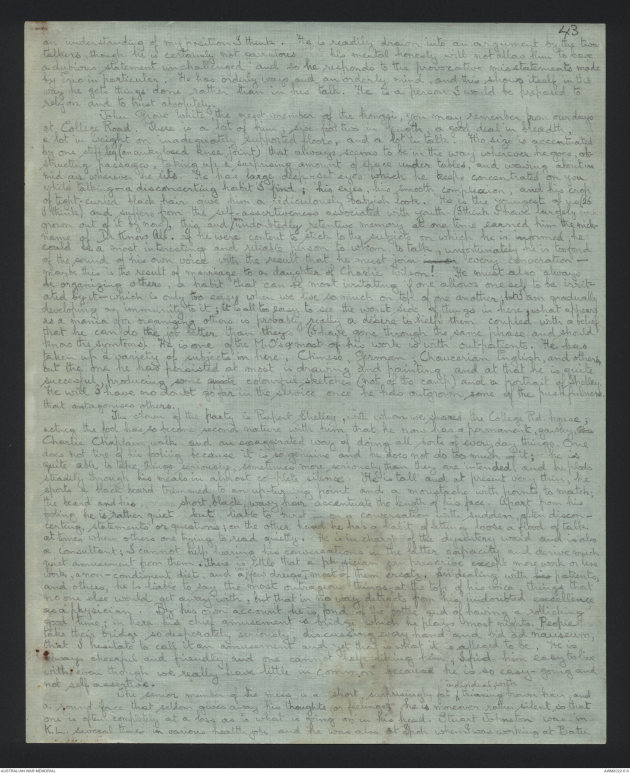

43

an understanding of my position I think. He is readily drawn into an argument by the two

talkers, though he is certainly not cautious his mental honesty will not allow him to leave

a dubious statement unchallenged and so he responds to the provocative misstatements made

by Eric in particular. He has orderly ways and an orderly mind, and this shows itself in the

way he gets things done rather than in his talk. He is a person I would be prepared to

rely on and to trust absolutely.

John Grove White, the next member of the barrage, you may remember from our days

at College Road. There is a lot of him, six foot two in length, a good deal in breadth,

a lot in weight on inadequately supported floors, and a lot in talk. His size is accentuated

by one stiff leg (an ankylosed knee joint) that always seems to be in the way wherever he goes,

obstructing passages, taking up a surprising amount of space under tables, and waving about in

mid air wherever he sits. He has large deep set eyes which he keeps concentrated on you.

while talking a disconcerting habit I find, his eyes, his smooth complexion, and his crop

of tight curled black hair give him a ridiculously babyish look. He is the youngest of us (26

I think) and suffers from the self-assertiveness associated with youth (I think I have largely [[?]]

grown out of it by now), this and ^an undoubtedly retentive memory at one time earned him the nick

name of Dr Know All. If he were content to stick to the subject on which he is informed, he

could be a most interesting and reliable person to whom to talk, unfortunately he is too fond

of the sound of his own voice with the result that he must join xxxxx every conversation -

maybe this is the result of marriage to a daughter of Charlie Wilson! He must also always

be organizing others, a habit that can be most irritating if one allows oneself to be irritated

by it which is only too easy when we live so much on top on one another, but I am gradually

developing my immunity to it, it is all too easy to see the worst side of things in here, what appears

as a mania of organizing others is probably really a desire to help them coupled with a belief

that he can do the job better than they (I have gone through the same phase and should

know the symptoms). He is one of the M.O.'s & most of his work is with outpatients. He has

taken up a variety of subjects in here, Chinese, German, Chaucerian English, and others

but the one he has persisted at most is drawing and painting and at that he is quite

successful, producing some quite colourful sketches (not of the camp) and is portrait of Shelley.

He will I have no doubt go far in the service once he has outgrown some of the [[?push]] fulness

that antagonises others.

The clown of the party is Rupert Shelley, with whom we shared the College Rd. house;

acting the fool has so been second nature with him that he now has a permanent, gawky, xxx

Charlie Chaplain walk and an exaggerated way of doing all sorts of everyday things. One

does not tire of his fooling because it is so genuine and he does not do too much of it; he is

quite able to take things seriously, sometimes more seriously than they are intended and he plods

steadily through his meals in almost complete silence. He is tall and at present very thin. he

sports a black beard trimmed to an upturning point and a moustache with points to match;

the beard and his [[?]] short, black, wavy hair accentuate the length of his face. Apart from his

fooling he is rather quiet but liable to burst into a conversation with sudden often disconcerting,

statements or questions, on the other hand he has a habit of letting loose a flood of talk

at times when others are trying to read quietly. He is in charge of the dysentery ward and is also

a consultant; I cannot help hearing his conversations in the latter capacity and derive much

quiet amusement from them. There is little that a physician can prescribe except more work or less

work, a non-condiment diet, and a ^ [[?]] few drugs most of them [[?]] for treating his patients

and others, he is liable to say the most outrageous things at the top of his voice, things that

no one else would get away with, but that in no way detracts from his undoubted excellence

as a physician. By his own account he is fond of the bottle and of having a rollicking

good time; in here his chief amusement is bridge which he plays most nights. People

take their bridge so desperately seriously discussing every hand and bid ad nauseum,

that I hesitate to call it an amusement and yet that is what it is alleged to be. He is

always cheerful and friendly and one cannot help liking him, I find him easy to live

with even though we really have little in common because he is so easy-going and

not self assertive.

The union member of the mess is a short, surprisingly fat ^ individual, with thinning brown hair, and

a sound force that seldom gives away his thoughts or feelings he is moreover rather silent in that

one is often completely at a loss as is what is going on in his head. Stuart Johnston was in

K.L. several times in various health jobs and he was also at [[?S]] when I was working at Batu

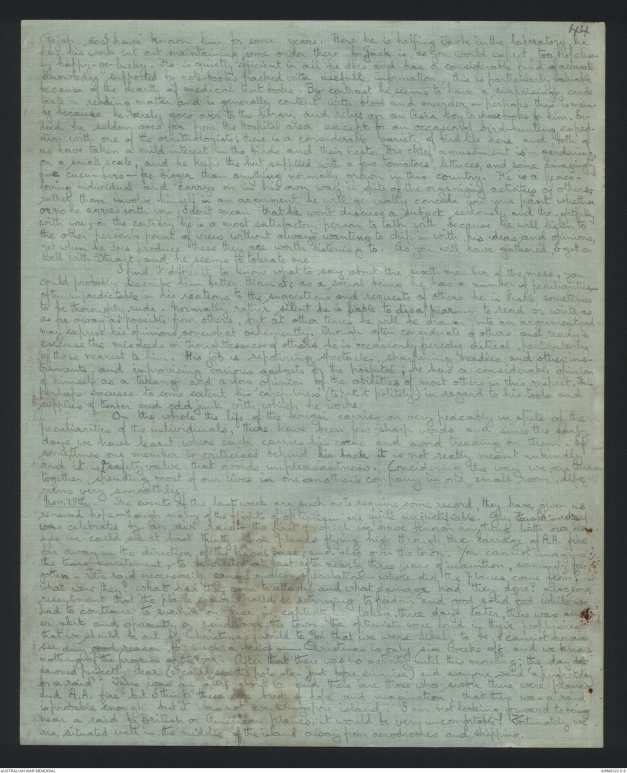

44

[?] [?] have known him for some years. Here he is helping Jack in the laboratory, he

has his work cut out maintaining some order there for Jack is as you would expect, too hopelessly

happy-go-lucky. He is quietly efficient in all he does and has a considerable find of accurate

knowledge supported by notebooks packed with usefull information, this is particularly valuable

because of the dearth of medical text books. By contrast he seems to have a surprisingly crude

taste in reading matter and is generally content with blood and murder - perhaps this is mainly

because he rarely goes over to the library and relies on an Asia boy to choose books for him. Indeed

he seldom goes far from the Hospital area except on an occasional bird-hunting expedition

with one of the ornithologists; there is a considerable variety of bird life here and both of

us have taken a mild interest in the birds and their nests. His chief amusement is in gardening,

on a small scale, and he keeps the hut supplied with a few tomatoes, lettuces and some amazingly

fine cucumbers - far bigger that anything normally grown in this country. He is a peace-loving

individual and carrys on in his own way in spite of the organizing activities of others;

rather than involve himself in an argument he will generally concede you your part whether

or not he agrees with you; I don't mean that he won't discuss a subject seriously and thoughtfully

with you, on the contrary he is a most satisfactory person to talk with because he will listen to

the other person's point of views without always wanting to chip in with his ideas and opinions,

yet when he does produce these they are worth listening to. As you will have gathered, I get on

well with Stuart, and he seems to tolerate me.

I find it difficult to know what to say about the sixth member of the room, you

could probably describe him better than I; as a social being he has a number of peculiarities

often unpredictable in his reactions to the suggestions and requests of others he is liable, sometimes

to be thoroughly rude. Normally rather silent he is liable to disappear to read or write as

as far away as possible from others, but at other times he will be drawn into an argument and

may express his opinions somewhat vehemently. Though often considerate of others and ready to

excuse the misdeeds or thoughtlessness of others he is occasionally fiercely critical, particularly

of those nearest to him. His job is repairing spectacles, sharpening needles and other instruments

and improvising various gadgets for the hospital; he has a considerable opinion

of himself as a [?] and a faux opinion of the abilities of most others in this respect. This

perhaps excuses to some extent his 'carefulness' (to put it politely!) in regard to his tools and

supplies of timber and odd junk with which he works.

On the whole the life of the kongui carries on very peacably in spite of the

peculiarities of the individuals, there have been few sharp words said since the early

days we have learnt where each carries his [?] and avoid treading on them. If

sometimes one member is criticised behind his back it is not really meant unkindly

and it is ^a safety valve that avoids unpleasantness. Considering the way we are thrown

together, spending most of our lives in one another's company in one small room, life

runs very smoothly.

Nov 19th. The events of the last week are such as to require some record, they have given us

renewed hope - though many of the flights of optimism are quite unjustifiable. Guy Fawkes day

was celebrated by an air raid! - the first of which we have [?] anything. With our

[[?eyes]] we could see at least thirty [?] planes flying high through the barrage of A.A. fire

far away in the direction of the Naval Base, and also over the town. You cannot imagine

the tense excitement, to be ordered at last after nearly three years of inaction, seemingly forgotten.

The raid necessarily caused endless speculations - where did the planes come from?

What were they? What had they come to attack? and what damage had they done? Also some

resentment that the plane crew should be returning to freedom and good solid food while we

had to continue to survive on rice in captivity! When, three days later, there was an

in albeit and apparently a raid over the town the optimists were loud in their prophesies

that we should be out by Christmas; would to God that we were likely to be I cannot however see any good reason for such a belief - Christmas is only six weeks off and we know

nothing of the progress of the war. After that there was no activity until this morning; thie day xx

dawned perfectly clear (we could see the pole star just before sunrise) and everyone said 'a perfect day

for a raid?' There was an alert about 10 and there are those who swore there was a raid

and A.A fire but I think these were bred of hope and imagination, that there was a raid

is probable enough but it was not ever Singapore Island. I am not looking forward to being

near a raid by British or American planes, it would be very uncomfortable! Fortunately we

are situated well in the middle of the island away from aerodromes and shipping.

45

There is a strange change in the hospital. Two and a half years of exclusive masculinity

has come to an end and Sisters are now allowed to come and nurse the very sick. With

the exception of a single trained male nurse - who is called 'Matron' - the hospital has been

run all this time by untrained volunteers, they have been most willing and patient with all

sorts of difficult patients and cope cheerfully with the most primitive conditions but naturally

they have not much idea of real nursing. It is a boon to the M.Oo and a great benefit to the

patients to have the Sisters. Only two are allowed over at time and they take four hour shifts

from 8am. to 8pm. They are only allowed to talk to men on matters connected with their

work! My affairs seldom take me to the hospital so I seldom see them except on their way

to and from their work when they go past my front door. Patie is among those who come over,

she seems fit, though is thin as ever, and cheery in spite of expressing considerable boredom

with internment - a fairly universal sentiment. Many of the women we see over here are agressively

fat by contrast with the very skinny appearances of most of the men. They get no more

to eat than us now - less, but they have no physical work to do and smaller bodies to keep

up. Many men are pathetically thin, they have no fat left and their flesh too has fallen away

so that their stringy muscles can be seen working under the thin skin, it is often difficult

to recognise a person who one has not seen for some months. The older men and tall are the

worst, they have shrunk piteously; most young folk have maintained a decent weight, they

are neither fat nor thin; and many of the smaller men are very well covered - they get more

than enough food. I seem to have wondered away from the sisters: they come over here

attired in their usual spotless white uniform & flowing white cap, how they manage it after

all these months I do not know, they stand out like swans against a coal heap in contrast

with our nakedness and rags.

The other day I was thrilled beyond measure to receive the photo of the babes, I

jumped for joy and cooed and behaved like a child. They all have very professional grins

but it is lovely for all that. Mickey of course is unrecognisable and they have all obviously

matured; and it makes me rather miserable to think of what I have missed (this seems

to be reflected in the verse I have been scribbling recently for my own amusement). I later

received another copy enclosed in a letter from Graham which it was grand to have. Then

I got your radio less than a month old, it is marvellous to have such recent news of you,

to know that you are all well, and that you intend to stay where you are until my return?

The last statement, by the way, went all the way round the camp growing as it travelled,

and several people came to ask me if it was true that I had had a radio saying that we

should be repatriated next month! Another letter from you was less cheering, it was dated

1st January 1944 and said 'hoping for better things in New Year!' Which new year? We go on

hoping, and saying "it can't be long now", but the beastly show drags on and we seem

no nearer the end than we were in March 1942, further, because then we could not believe

that hostilities would last three months out here and now there seems no prospect of

our being out in the next six months, it may be many more.

Manning has died from Tropical Typhus, or rather from a whole series of

complications, for he hung on a long time and it looked as though he was [[?pocked]] the

worst when one night he passed out. There have been a lot of deaths recently but

mostly among the old men, many of whom have hung on longer than even they would

outside.

17th Jan 1945. We have started a new year with less confidence than on previous occasions that

it is to be our last, we say to one another, 'It must finish this year' but knowing in our hearts

that there is no 'must' about it. The more frequent air raids inspire unreasoned hope, but at the

same time misery over the further horrible loss of life that there must be if, as one fears, some of

the bombs land in the crowded tenements round the aerodrome and other objectives. I don't like

air raids any more than I did three years ago, the fact that they are our own planes gives a small

level of confidence and to see those huge planes sailing majestically overhead undestroyed by

the attacks of the fighters is rather encouraging, but the sound of gunfire, bombs, and the occasional

whine of a falling dead shell or nose cap is still unpleasant. Nor is it nice to see one of

our planes shot down in flames as happened once recently.

We got what cheer we could out of the festive season. The kitchen did us very

well both in quantity and quality, they saved up for the occasion with the result that for

the first time for a year I was uncomfortably distended. The food was of course mainly

rice disguised in various ways; a sweetened kunji for breakfast and a monumental

46

rice-maize bun with a large lump of lard, savoury rice & the usual soup for lunch, but with

just that little extra in flavouring, and at tea in addition to the sweetened kunji, and I think

a sweet potato hash, a marvellous 'cake' - how they made it with the few ingredients

available I cannot even guess, but it tasted extraordinarily good. We had plenty left over

for a supper at night which we washed down with a mugfull of beer that we brewed ourselves.

Perhaps the last item sounds pretty terrible to you, but we appreciated it quite as much as

the best that Mr. Guiness ever brewed. After that we sang cheerfully - not that the songs

in which Rupert had us were altogether apropriate to the season.

The high spot of the day was the meeting with the ladies in the orchard from 210

to 4.0pm. It was an amazing scene - (I tried to record it in prose but as so often happens

my muse flagged half way). There must have been over a thousand of us: the ladies

all tricked out in their finery, and in spite of three years internment they got themselves

up very attractively; and the men outnumbering them two or three to one and also in

their best, mostly only shorts & shirts but these fresh and tidy, and a few resplendent in

flannels - even ties - I was invited by Dorothy B. to drink tea with her at 3.0 and I gather

that she had been round warning off any others who might take it into their heads to invite

either Jack or myself! Before that I had time to join (uninvited) Miss. Griff's party.

and also to have a few words with Adie Patie and another Sister. Miss Griff was very cheery

and full of chat and it was very pleasant to be able to talk freely to her about you and the

babes as well as others who are not here. Dorothy looked very well and was certainly enjoying

her afternoon out - the ladies get less variety out of life. than we do being more

restricted in their movements and having little to do in the way of fatigues. The food

that our hostesses produced was an amazing achievement & Miss. Griff gave us a very

racy account of her efforts at cake making. How all sorts of people had given her bits

of the most unlikely things to add to it, from the original ground rice to the final taste of

ginger - the result was most tasty. Adie had some butter sweet buns and Dorothy

some ginger biscuits, all very good to our palates. It seems ridiculous that only

should we be allowed to meet our friends in the ladies camp, what harm could come from

more frequent meetings I cannot think & of course relatives & relations meet every Sunday.

The day was rounded off with a concert, nothing very outstanding but quite enjoyable

- the first large-scale concert since before 10.10.43. I forgot that on Christmas Eve we

had a Carol service in the orchard, ladies on one side of the [?] church and men on

the other. The carols were sung by the choir or by the whole congregation - it gave one

a strange thrill when the ladies sang a verse by themselves. The Bishop, in his

purple robes presided, assisted by a very American padre who gave us the story of the

carols that were sung.

New Years day was celebrated with a party for the children of the men's camp &

I assisted with games, towards the end it looked like being a 'howling' success but

apart from that it went off well. I wouldn't have believed it possible for anyone to

eat what some of those kids put away; there was plenty left over after & I found one

child's portion to be comfortably filling; some of them consumed two or even three

portions! There was a concert in the evening distinguished principally by some professional

conjuring and clowning - the population of this camp includes representatives

of the most surprising professions.

I have achieved some notoriety by manufacturing spectacle frames. I make

them from the handles of old tooth brushes and am becoming so expert at it that I

can turn out five or six a week on top of a good deal of other work. They are

strong and almost indistinguishable from the real thing except for the somewhat

loud colours that I necessarily use. I understand that they are becoming eagerly

sought souvenirs in the women's camp, and the difficulty is to decide which are the

most deserving cases. It is just another of the many strange improvisations that internment

has produced, but one of the more spectacular (that is not meant as a pun).

Daily roll calls have recently been instituted after months without any such things at first they

were to be twice a day but what with rain and other excuses we never had one in the evening and

now they only take place on week-day mornings. They are a nuisance because at this time of year

it means getting up in the dark (7.30) and also shaving in the dark if one wants to get it done

before breakfast. As usual one can only speculate on the reason for the change: do our hosts now

think that there is sufficient incentive for us to run away?

47

Sunday evening services somewhat on the lines of a 'Scouts Own' have been started, partly with

the laudable object of keeping the kids out of mischief. The first was Dec 31st and Sands spoke

very well, keeping the interest of the unruly brats. I read the lesson! The third Sunday (when I had

to read again) the Service had to be held in a pig-stye for want of better accommodation - true the

stye is still in course of construction and has never yet been used for its alotted purposes.

In spite of early promises no new huts have been erected to lighten the gross overcrowding in

the camp and the wood cut by the sawmill is used to build pig styes and to make a [[?tall]]

fence around the camp. The original stimulus to start the services was provided by the

children themselves, but not in the form of a request for a service. There are two schools

in the men's camp, one for the R.C. children and the other - held in St. David's Church for

the rest. One Sunday evening the St. David's boys created bedlam near the R.C. church

and the following Sunday the R.C's retaliated by horse-play near St. Davids. The following

week, the two schools continued to play havoc with the united church service at the northern

end of the camp. The R.C's started an evening class for their boys and the Camp Police

impounded the more lively spirits among the St. David's boys for the duration of the evening

services. The special services are intended to keep the boys occupied during the regular services,

but I doubt whether they will continue to be attended for long unless there is some-

thing more than moral pressure behind them. The kids are a wild gang, getting very little

discipline either from their parents or from anyone else; of course the facilities for their amusement

are very few, toys, especially constructive ones, are almost non-existent and they are not

encouraged to try their hands with the few ageing tools. Just now there is a craze for butterflies

and caterpillars, small boys rush about with butterfly nets made from the leg of an old pair

of pyjamas fixed on the frame of a badminton racket, or some such improvisation. This afternoon

a shout greeted me, "Kaa!, come and look at my caterpillar" (Kaa is my Cub name). The

lad stooped to a bed of sweet potatoes and produced for my inspection a large handsome black

caterpillar which in due course he no doubt returned there; I didn't enquire whether it was only

put out to grass during the day and was returned to its stable at night or whether sheep like

it was left to graze unattended.

Last week Hotham and several other europeans were brought into the camp after nearly

three years 'liberty' in the town. After a few days' close confinement in the guard room they were

removed again taking with them seven days of rations; what has happened to them we do

not know. They have very unjustly been accused of being [?] by folk who can't think

themselves into the whoes of anyone but themselves. For myself, I have never ceased to be glad

that I refused to go and work with them more than two years ago, I should never have been

happy in the difficult situations in which they must often have been placed.

31st March. Much has happened since last I wrote: there have been drastic reductions in

the food, there has been an invasion of new internees, air raids have become more frequent, and we

have at long last, received a consignment of Red Cross comforts. Food is as usual the most important

subject in our thoughts and conversation. There have been two cuts in our rations, one about

a couple of months ago and another a month back, and we are threatened with further cuts until

August when we are told that we shall have to live on what we grow ourselves, if that be literally

true we shall die, for it is out of the question for us to produce sufficient food for between four and

five thousand internees. Every inch of the camp is under cultivation and considerable areas

oustide the camp, on the golf course and elsewhere, have been dug over and planted with tapioca.

But for grossly underfed Europeans of an average age of 45 to produce enough to live on is out of

the question, soon if we had a sufficient area of land ('European' aplies to a large but dominating

proportion of the camp). The cuts have brought us down to a ridiculously low level; about what

the physiologists consider adequate for a man lying in bed all day! and yet we continue to work

on it and do not as yet feel much the worse. We are of course all losing weight and are

constantly hungry, though not ravenously so. Some of the heavier workers - wood cutters,

special changkaling gangs, and construction gangs - get extra rice and tapioca, but still

far from adequate. Most people have managed to buy red palm oil for themselves to enhance

their diets quite materially; we here take about an ounce a day mixed into our morning kunji

(of rice and maize) or into any other dish that will carry it. The difficulty is to get the palm oil.

A certain amount comes in through legitimate channels and is sold at about $1 a half pint,

but much more comes in through the black market and various other unofficial channels.

And the price then ranges up to $8 for the same quantity. I got two for your old watch

which at current rates of exchange was good value. The currency has long ago ceased

48

to have any relation to its pre-war purchasing value. So far as one can judge the dollar is

about worth one cent in Singapore, many imported goods naturally have a scarcity value

and their prices are even more fantastic. Articles of volume are said to be sold by the inch

or $10 notes! By way of contrast our monthly salaries from the Nipponese are $12., enough

to purchase two duck eggs at current rates! The result is naturally that people part with

their few valuables in exchange for cash or goods. The former particularly is an unsatisfactory

procedure because those who operate the black market take their rake-off both

ways, and they are not philanthropists. Others obtain cash by writing cheques at the pre-war

rate of exchange; the grossest form of profiteering on the part of those who supply the cash,

but regarded in this gilbertian camp merely as good business. As usual the kitchen does

wonders with the meagre fare: kunji for breakfast; savoury rice (rice with a little fat or oil

and ikam feles) and vegetable soup, or a vegetable hash containing some rice, root vegetables,

leaf, belio and much water as filling; for tea there is always a rice-maize bun

(much the same as the kunji but baked to a semi-solid consistency), 'sea pie' of rice, veg. +

dried fish of some sort baked in a pan, or rissoles of much the same composition

but fried up to resemble rissoles in appearance and also, on the more auspicious occasions,

in taste.

The arrival of the Red Cross comforts is one of the most momentous events in our

lives. After more than three years of internment we are each to receive a whole parcel

such as a prisoner in Europe would receive once a fortnight; more, we expect to get a

British parcel each, plus about a half share in a British, Canadian or American parcel.

There are also bulk consignments of cigarettes, books, boot repairing outfits, miscellaneous

comforts and medical supplies. The last are, immensely valuable. We have

had to subsist on what we were able to purchase in the early days. [[?]] on very meagre

supplies from the Nips, and on what we can improvise ourselves. Now we are liberallywell supplied with most of the essential drugs that we need; some that are new to the

country, and one of which we are ignorant of its use. There is also much sorely needed

equipment - hypodermic syringes, bandages, gauze, etc. Of course there are [?]

such as large quantities of vitamin A & D preparations, of which vitamins we have a super-

abundant supply in palm oil and vegetables. I said that we improvised drugs, and

I meant it. The chemists prepare 'kolin' for the treatment of tummies out of clay from the

garden; they make an efficient purgative from 'galangang', a swamp shrub with large spikes

of golden yellow flowers that you must remember; a diuretic is prepared from the leaves

of 'khunin kuching' a small garden plant; and there are other improvisations with which

I won't weary you. Of such is our pharmacopeia. The food parcels have still to be released

by the Nips - they seem to be behaving on the matter like the little girl who only did it to annoy. It is

hard after we have waited so long.

During the last week nearly a thousand new internees have been squeezed into the camp.

They are mostly Jews and Eurasians and more than half are women and children. The Jews

are of course from Singapore but the Eurasions are from all over the country; Penang, Perak,

Selanga, & N.S. including quite a number from Bahau where a settlement for Eurasians has

been started. Last June about 2,000 of them were given plots of newly felled jungle about five miles

from Bahau and told to get on with it. They were given rice enough to last them, six months

after which they were to be self sufficient. Apart from malaria which is rampant, they seem to

have got on well and to have enjoyed the life and to be able to support themselves in reasonable

comfort. They lived on Tapioca, sweet potatoes, beans, peanuts, and on game trapped in the

adjacent jungle and not at all a bad life I should think. All from upcountry have most interesting

tales to tell of conditions in the country generally, conditions of which we were totally

ignorant. It is clear that in many respects we shall return to a very different country

from the one we knew ...... The accounts of the damage wrought by our planes are extraordinary.

I suppose that it is necessary for the prosecution of the war, but one wonders

when the damage can ever be made good again, and whether in particular, the railways

will ever be reopened. The loss of life other than Nipponese, seems to have been small apart

from the tragedy of Central workshops where the people appear to have been trapped in the shops

and settlement and these very many casualties. There is news of some of our Eurasian

and Asiatic friends, but it is meagre and it is difficult after three years to put one back

into one's old life to remember all of whom one should make enquiries. There is little and

unhelpful information about the J.N.R. beyond what we already knew.

49

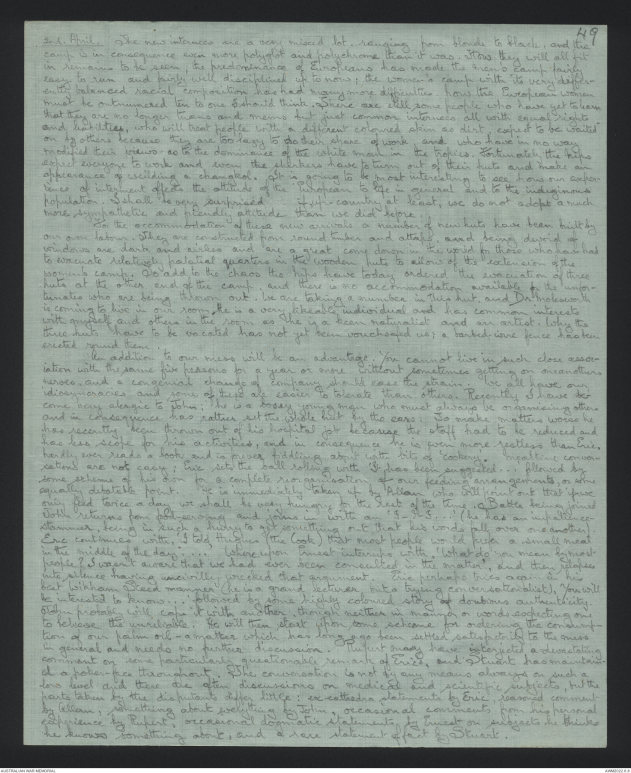

2nd April. The new internees are a very mixed lot, ranging from blonde to black, and the

camp is in consequence even more polyglot and polychrome than it was. How they will all fit

in remains to be seen, the predominance of Europeans has made the men's camp fairly

easy to run and fairly well disciplined up to now, the women's camp with its very differently

balanced racial composition has had many more difficulties. Now the European women

must be outnumbered ten to one I should think. There are still some people who have yet to learn

that they are no longer mams and mems but just common internees all with equal rights

and [[?hostilities]], who will treat people with a different coloured skin as dirt expect to be waited

on by others because they are too lazy to do their share of work and who have in no way

modified their views as to the dominance of the white man in the tropics. Fortunately the Nips

expect everyone to work and even the shirkers have to turn out of their huts and make an

appearance of wielding a changkol. It is going to be most interesting to see how our experience

of internment affects the attitude of the European to life in general and to the indiginous

population. I shall be very surprised [[?]] if, up-country at least, we do not adopt a much

more sympathetic and friendly attitude than we did before.

In the accommodation of these new arrivals a number of new huts have been built by

our own labour. They are constructed from round timber and [[attaps]], and being devoid of

windows are dark and airless and are a great come down in the world for those who have had

to evacuate relatively palatial quarters in the wooden huts to allow of the extension of the

women's camp. To add to the chaos the Nips have today ordered the evacuation of three

huts at the other end of the camp, and there is no accommodation available for the unfortunates

who are being thrown out. We are taking a number in this hut and Dr. Molesworth

with myself and others in the room as he is a keen naturalist and an artist. Why the

three huts have to be vacated has not yet been vouchsafed us; a barbed wire fence has been

erected round them

An addition to our mess will be an advantage. You cannot live in such close association

with the same five persons for a year or more without sometimes getting on one anothers

nerves, and a congenial change of company should ease the strain. We all have our

idiosyncracies and some of these are easier to tolerate than others. Recently I have become

very alergic to John; he is a bossy young man who must always be organising others

and in consequence has rather set the whole hut by the ears. To make matters worse he

has recently been thrown out of his hospital job because the staff had to be reduced and

has less scope for his activities, and in consequence he is even more restless than Eric,

hardly every reads a book and is forever fiddling about with bits of 'cookery. Mealtime conversations

are not easy; Eric sets the ball rolling with 'It has been suggested ......' followed by

some scheme of his own for a complete reorganisation of our feeding arrangements, or some

equally debatable point. He is immediately taken up by Allan who will point out that 'if we

only feed twice a day we shall be very hungry for the rest of the time. Battle being joined

John returns from food-serving and joins in with an 'I-or I....' (he has an impatience-

stammer, being in such a hurry to get something out, that his words fall over one another).

Eric continues with 'I told Hughes (the Cook) that most people would prefer a small meal

in the middle of the day.....' Where upon Ernest interrupts with 'What do you mean by most

people? I wasn't aware that we had ever been consulted in the matter'. and then relapses

into silence having unwillingly wrecked that argument. Eric perhaps tries again in his

best Wikham Steed manner (he is a grand lecturer but a trying conversationalist), 'You will

be interested to know....' followed by some highly coloured story of doubious authenticity.

John probably will, cap it with another, though neither in manner or words expecting one

to believe the unbelievable. He will then start upon some scheme for ordering the constuction

of our palm oil in a matter which has long ago been settled satisfactorily to the mess

in general and needs no further discussion. Rupert may have interjected a devastating

comment on some particularly questionable remark of Erics, and Stuart has maintained

a poker-face throughout. The conversation is not by any means always on such a

low level and there are often discussions on medical and scientific subjects, but the

parts taken by the disputants differ little : ex-cattedra statements by Eric, reasoned comment

by Allan, something about everything by John, occasional comments from his personal

experience by Rupert, occasional dogmatic statements by Ernest on subjects he thinks

he knows something about, and a rare statement of fact by Stuart.

50

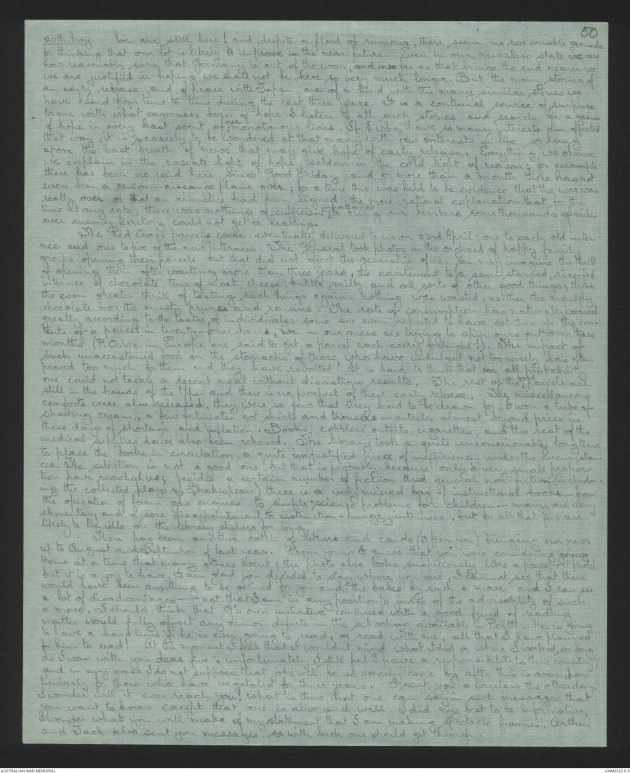

20th May. We are still here! and despite a flood of rumours, there seems no reasonable grounds

for thinking that our lot is likely to improve in the near future. Even in our newsless state we are

now reasonably sure that Germany is out of the war, and in so far as that brings the end nearer we

we are justified in hoping we shall not be here so very much longer. But the many stories of

an early release and of peace with Japan are of a kind with the many similar stories we

have heard from time to time during the last three years. It is a continual source of surprise

to me with what eagerness born of hope. I listen to all such stories and search for a grain

of hope in every last event of ^our monotonous lives. If I who have so many interests am affected

that way, it is scarcely to be wondered at that many with few interests in life so hang

upon the least breath of 'news' that may give hope of early release. Everything we observe

we explain in the rosiest light of hope, seldom in the cold light of reason: for example

there has been no raid here since Good Friday and for more than a month there has not

even been a reconnaissance plane over; for a time this was held to be evidence that the war was

really over or that an armistice had been signed, the more rational explanation that, for the

time at any rate, there was nothing of sufficient ^importance to bring our bombers some thousands of miles over enemy territory could not get a hearing.

The Red Cross parcels were eventually delivered to us on 23rd April; one to each old internee

and one to give to the new internees. The General took photos in the orchard of happy family

groups opening their parcels but that did not affect the generality of war. You may imagine the thrill

of opening them after waiting more than three years, the excitement to a semi starved rice-fed

internee of chocolate, tins of meat, cheese, butter, milk and all sorts of other good things; then

the even greater thrill of tasting such things again. Nothing was wasted, neither the mouldy

chocolate nor the musty prunes and raisins. The rate of consumption has naturally varied

greatly according to the tastes of individuals some are even reported to have got through the contents

of a parcel in twenty-four hours, we in our mess are trying to spin ours out over three

months (P.O.W in Europe are said to get a parcel each every fortnight!). The impact of

such unaccustomed food on the stomachs of those who have indulged not too wisely has often

proved too much for them and they have revolted! It is hard to think that in all probability

one could not tackle a decent meal without disastrous results. The rest of the ^food parcels are

still in the hands of the Nips and there is no prospect of their early release. The miscellaneous

comforts were also released, they were so few that they had to be drawn for & I won a tube of

shaving cream, a few fortunates got shirts and trousers - articles almost beyond price in

these days of shortage and inflation. Books, cobblers outfits, cigarettes, and the rest of the

medical supplies have also been released. The library took a quite unconscionably long time

to place the books in circulation, a quite unjustified piece of inefficiency under the circumstances.

The selection is not a good one, but that is probably because only a very small proportion

have reached us; besides a certain number of fiction and general non-fiction (including

the collected plays of Shakespeare) there is a very mixed bag of instructional books from

the operation of farm gas engines to simple science problems for children - many are very

elementary and a sore disappointment to instruction - hungry internees, but for all that few are

likely to be idle on the library shelves for long.

There has been another batch of letters and cards (3 from you) bringing us news

up to August and September of last year. From yours I guess that you were considering going

Home at a time that many others went & the photo also looks suspiciously like a passport photo!

but it is a joy to have. I am glad you decided to stay where you are, I cannot see that there

would have been anything to be gained for you and the babes by such a move and I can see

a lot of disadvantages - not that I am in any position to judge of the advisability of such

a move. I should think that G's own initiative combined with a good friend of reading

matter would fully offset any minor defects in the schooling available in Perth. He is going

to have a hard time if he is ever going to read, or read with me, all that I have planned

for him to read! At the moment I feel that I wouldn't mind what I did or where I worked so long

as I was with you dear five, unfortunately I still feel I have a responsibility to this country.

and in any case I do not suppose that jobs will be as easily come by after this is over particularly

for those who have vegetated for three years. I sent you a wireless the other day

I wonder will it ever reach you! What is there that one can say in such messages that

you want to know except that one is alive and well. I did my best to be informative,

I wonder what you will make of my statement that I am making spectacle frames. Arthur

and Jack also sent you messages so with luck one should get through.

Transcriber 206

Transcriber 206This transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.