Papers written by Hodgkin, Ernest P. (Doctor, b.1908 - d.1998) - Part 6

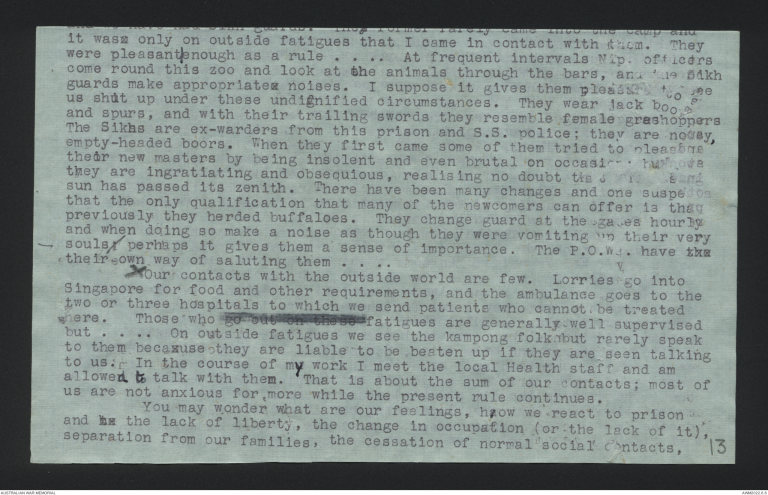

it was only on outside fatigues that I came in contact with them. They

were pleasant enough as a rule.... At frequent intervals Nip. Officers

come round this zoo and look at the animals through the bars, and the sikh

guards make appropriate noises. I suppose it give them pleasure to see

us shut up under these undignified circumstances. They wear jack boots

and spurs, and with their trailing swords they resemble female grasshoppers.

The Sikhs are ex-warders from this prison and S.S. police; they are [nocsy?]

empty-headed boors. When they first came some of them tried to please

their new masters by being insolent and even brutal on occasion to [?]

they are ingratiating and obsequious, realising no doubt the [?]

sun has passed its zenith. There have been many changes and one suspects

that the only qualification that many of the newcomers can offer is they

previously they herded buffaloes. They change guard at the [?] hourly

and when doing so make a noise as though they were vomiting up their very

souls; perhaps it gives them a sense of importance. The P.O.W.'s have xxx

their own way of saluting them.......

Our contacts with the outside world are few. Lorries go into

Singapore for food and other requirements, and the ambulance goes to the

two or three hospitals to which we send patients who cannot be treated

here. Those who go out on the s fatigues are generally well supervised

but..... On outside fatigues we see the kampong folk but rarely speak

to them because they are liable to be beaten up if they are seen talking

to us. In the course of my work I meet the local Health staff and am

allowed to talk with them. That is about the sum of our contacts; most of

us are not anxious for more while the present rule continues

You may wonder what are our feelings, how we react to prison

and the lack of liberty, the change in occupation (or the lack of it),

separation from our families, the cessation off normal social contacts,

13

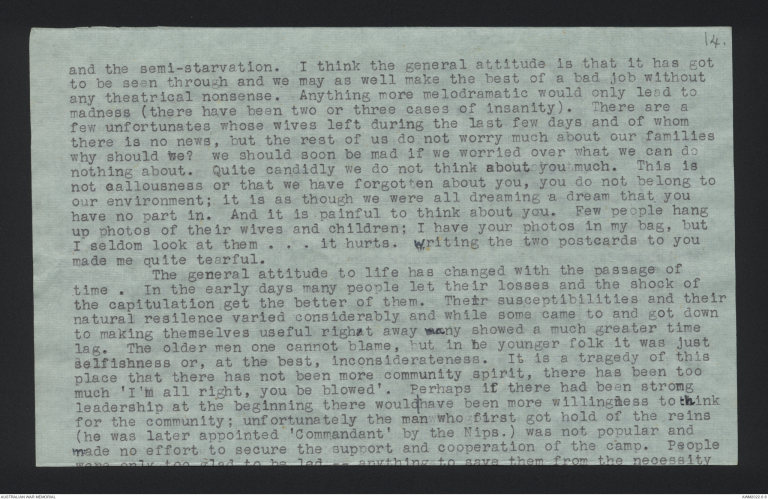

and the semi-starvation. I think the general attitude is that it has got

to be seen through and we may as well make the best of a bad job without

any theatrical nonsense. Anything more melodramatic would only lead to

madness ( there have been two or three cases of insanity). There are a

few unfortunates whose wives left during the last few days and of whom

there is no news, but the rest of us do not worry much about our families

why should we? we should soon be mad if we worried over what we can do

nothing about. Quite candidly we do not think about you much. this is

not callousness or that we have forgotten about you, you do not belong to

our environment; it is as though we were all dreaming a dream that you

have no part in. And it is painful to think about you. Few people hang

up photos of their wives and children; I have your photos in by bag, but

I seldom look at them. . . it hurts. writing the two postcards to you

made me quite tearful.

The general attitude to life has changed with the passage of

time. In the early days many people let their losses and the shock of

the capitulation get the better of them. Their susceptibilities and their

natural resilence varied considerably and while some came to and got down

to making themselves useful right away many showed a much greater time

lag. The older men one cannot blame, but in the younger folk it was just

selfishness or, at the best, inconsiderateness. It is a tragedy of this

place that there has not been more community spirit, there has been too

much 'I'm all right, you be blowed'. Perhaps if there had been strong

leadership at the beginning there would have been more willingness to think

for the community; unfortunately the man who first got hold of the reins

(he was later appointed 'Commandant' by the Nips.) was not popular and

made no effort to secure the support and cooperation of the camp. People

were only too glad to be led.. anything to save them from the necessity

of thinking for themselves--- but when on recovering consciousness they

found the camp just drifting they only offered carping criticism of those

who/were doing their best in their small way. This seems a gloomy

story but it is relieved by the many public-spirited individuals who have

done their best from the start (only to have all sorts of false motives

imputed to them). Things are very different now; the realisation that

willy nilly we may have to live here for years, and that we shall not

tomorrow be translated to some better sphere by some miraculous interven-

tion, has induced most people to try and make themselves useful in some

way. Those who just sit and think or sometimes just sit, are now only a

small minority, there is no lack of volunteers for any new permanent

fatigue, and even the routine fatigues seem to be done more cheerfully.

There seems to be a healthier spirit in the camp.

'Wishful thinking' is an overworked expression and in Changi it

is also an overworked faculty. Even in the first few weeks we expected

to be exchanged or relased in some mysterious manner, and rumours of our

imminent repatriation have recurred with such regularity that one might

suppose them to have been coined by someone who wished to buoy us up with

hope. Rumours have been founded on propaganda in the local rag, and a

few on authentic statements by Nips. xxxxxxxxxxx, but most have

originated miasma-like from the impact of an over-heated imagination on

a simple statement by a person of no authority. Once such rumour cent-

ered round a conversation I had with Mr. Asahi (Supervisor of Civilian

Internment Camps), and by the time it came back to me it was so embellished

that it was unrecognisable, except that my name was attached to it. The

expectation of early repatriation may have prevented some weak-minded

drones from loosing their reason, but it has had a very unsettling effect,

and for many it is the excuse -- though possibly unconscious -- for their

14

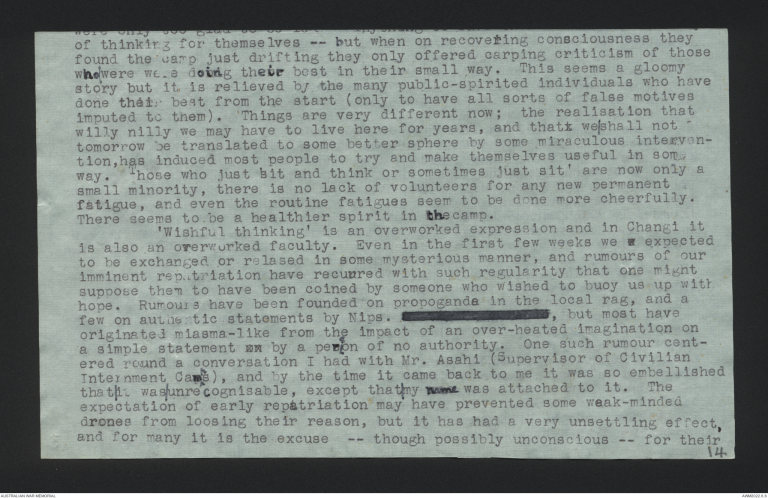

doing nothing useful. Probably we are all a bit mad or the fantastic

rumours that circulate from time to time would never be given credence.

In Changi it has intrigued me to discover how few are one's essen-

tial requirements. Like most others I arrived here with what would go into

a kit bag and a rucksack, and I was fortunate enough to have a roll of

bedding. If we were to go to liberty tomorrow the rucksack would hold

all that I really want. In spite of what you call my property complex I

feel little regret for what is lost. I am very/sad to loose the children's

photos, and the records of eleven years work do not bear thinking about;

I would very much like my tools, typewriter, and many of my books, but I

cannot feel any overwhelming sense of loss; maybe I shall when they have

to be replaced. We have all managed to acquire more belongings than we

brought with us, some by gift or purchase and many be scrounging. (There

is hones scrounge, as for instance material collected from a dump of xxx

derelict lorries that has been my main source of timber, and dishonest

scrounge which is indistinguishable from theft, and there are all shades

of respectability in between. It is often best not to enquire into the

origins of things.) these acquisitions are few of them things that we

shall want to take away with us, except perhaps as souvenirs, but they

make life more tolerable: an infinite variety of stools, tables of sorts,

beds tat would have delighted Heath Robinson (mine is the springs from

the back seat of a car), bedding of sacks stuffed with coir, tins convert-

ed to drinking cups or cooking utensils, and a host of other contraptions.

We are nothing if not ingenious in our improvisations. Do not think that

any of us will refuse the comfort of decent beds, chairs, or crockery

after this, or prefer to live in overcrowded barracks and subsist on a

rice diet. My greatest material ambition is to sleep in a comfortable

bed with clean sheets and a long chair with comfortable cushions would

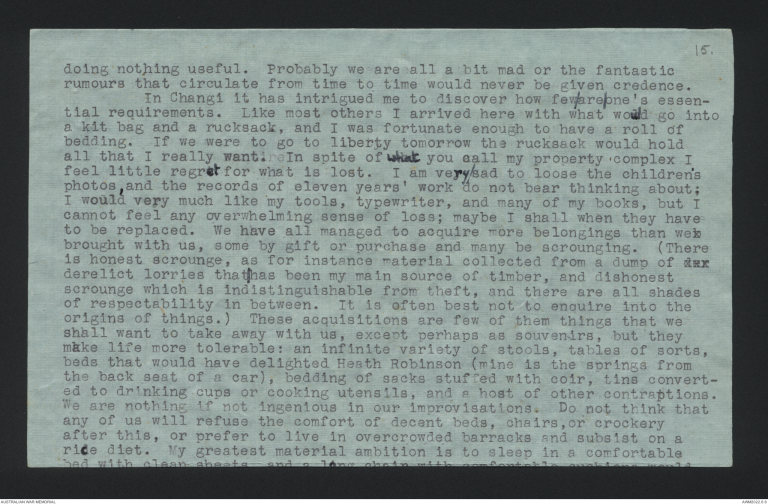

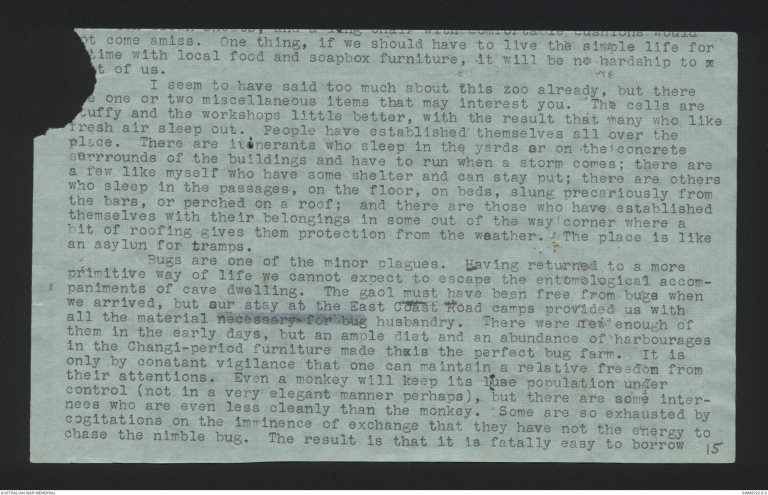

not come amiss. One thing, if we should have to live the simple life for

sometime with local food and soapbox furniture, it will be no hardship to

[?] of us.

I seem to have said too much about this zoo already, but there

are one or two miscellaneous items that may interest you. The cells are

stuffy and the workshops little better, with the result that many who like

fresh air sleep out. People have established themselves all over the

place. There are itinerants who sleep in the yards or on the concrete

surrounds of the buildings and have to run when a storm comes; there are

a few like myself who have some shelter and can stay put; there are others

who sleep in the passages, on the floor, on beds, slung precariously from

the bars, or perched on a roof; and there are those who have established

themselves with their belongings in some out of the way corner where a

bit of roofing gives them protection from the weather. The place is like

an asylum for tramps.

Bugs are one of the minor plagues. Having returned to a more

primitive way of life we cannot expect to escape the entomological accom-

paniments of cave dwelling. The gaol must have been free from bugs when

we arrived, but our stay at the East Coast Road camps provided us with

all the material necessary for bug husbandry. There were few enough of

them in the early days, but an ample diet and an abundance of harbourage

in the Changi-period furniture made this the perfect bug farm. It is

only by constant vigilance that one can maintain a relative freedom from

their attentions. Even a monkey will keep its louse population under

control (not in a very elegant manner perhaps), but there are some inter-

nees who are even less cleanly than the monkey. Some are so exhausted by

cogitations on the imminence of exchange that they have not the energy to

chase the nimble bug. The result is that it is fatally easy to borrow

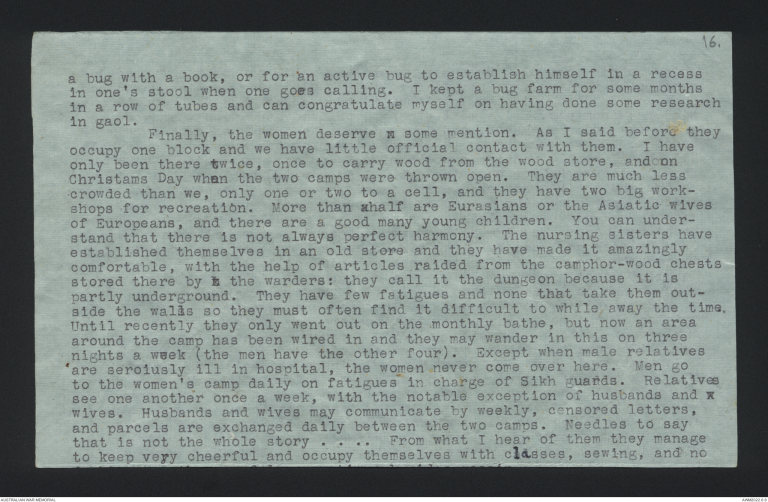

a bug with a book, or for an active bug to establish himself in a recess

in one's stool when one goes calling. I kept a bug farm for some months

in a row of tubes and can congratulate myself on having done some research

in gaol.

Finally, the women deserve some mention. As I said before they

occupy one block and we have little official contact with them. I have

only been there twice, once to carry wood from the wood store, and on

Christmas Day when the two camps were thrown open. They are much less

crowded than we, only one or two to a cell, and they have two big work-

shops for recreation. More than half are Eurasians or the Asiatic wives

of Europeans, and there are a good many young children. You can under-

stand that there is not always perfect harmony. The nursing sisters have

established themselves in an old store and they have made it amazingly

comfortable, with the help of articles raided from the camphor-wood chests

stored there by the warders: they call it the dungeon because it is

partly underground. They have few fatigues and none that take them out-

side the walls so they must often find it difficult to while away the time.

Until recently they only went out on the monthly bathe, but now an area

around the camp has been wired in and they may wander in this on three

nights a week (the men have the other four). Except when male relatives

are seriously ill in hospital, the women never come over here. Men go

to the women's camp daily on fatigues in charge of Sikh guards. Relatives

see one another once a week, with the notable exception of husbands and

wives. Husbands and wives may communicate by weekly, censored letters,

and parcels are exchanged daily between the two camps. Needless to say

that is not the whole story...... From what I hear of them they manage

to keep very cheerful and occupy themselves with classes, sewing and no

doubt many other occupations, besides gossip.

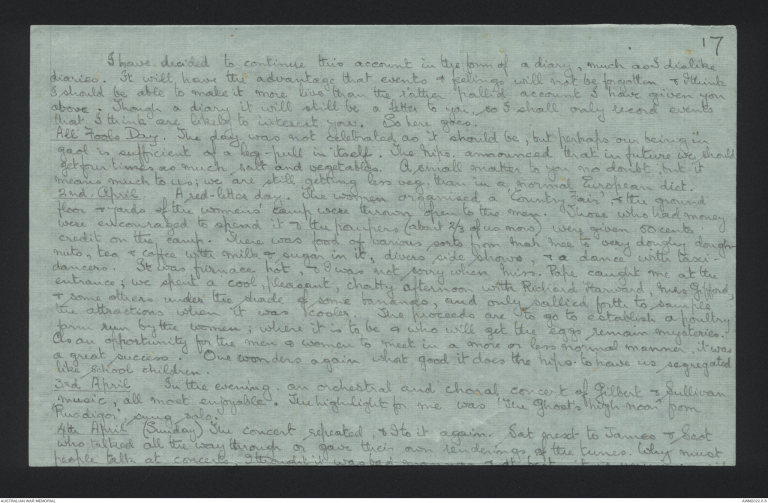

I have decided to continue this account in the form of a diary, much as I dislike

diaries. It will have the advantage that events & feelings will not be forgotten & I think

I should be able to make it more live than the rather pallid account I have given you

above. Though a diary it will still be a letter to you, so I shall only record events

that I think are likely to interest you. So here goes.

All Fools Day The day was not celebrated as it should be, but perhaps our being in

gaol is sufficient of a leg-pull in itself. The Nips announced that in future we should

get four times as much salt and vegetables. A small matter to you no doubt, but it

means much to us, we are still getting less veg. than in a normal European diet.

2nd April A red-letter day. The women organised a 'Country Fair', the ground

floor & yards of the women's camp were thrown open to the men. Those who had money

we encouraged to spend it & the paupers (about 2/3 of us now) were given 50 cents

credit on the camp. There was food of various sorts from [Nah?] [?] to very doughy dough-

nuts, tea & coffee with milk & sugar in it, divers side shows, & a dance with taxi-

dancers. It was furnace hot, & I was not sorry when Miss Pape caught me at the

entrance, we spent a cool, pleasant, chatty afternoon with Richard Harward, Mrs Gifford,

and some others under the shade of some bananas, and only sallied forth to sample

the attractions when it was cooler. The proceeds are to go to establish a poultry

farm run by the women, where it is to be & who will get the eggs remain mysteries.

As an opportunity for the men and women to meet in a more or less normal manner, it was

a great success. One wonders again what good it does the Nips to have us segregated

like school children.

3rd April In the evening an orchestral and choral concert of Gilbert & Sullivan

music, all most enjoyable. The highlight for me was "The Ghost's High Noon" from

Ruddigore, sung solo.

4th April (Sunday) The concert repeated, & I to it again. Sat next to James & Scot

who talked all the way through or gave their own renderings of the tunes. Why must

people talk at concerts, I thought it was bad manners & the best it was

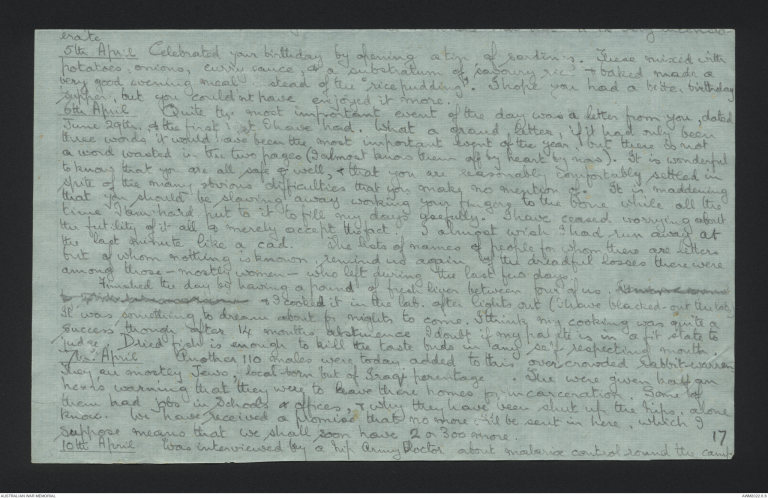

erate

5th April Celebrated your birthday by opening a tin of sardines. These mixed with

potatoes, onions, curry sauce at a substratum of savoury rice - baked made a

very good evening meal stead of the 'rice pudding'. I hope you had a better birthday

supper, but you couldn't have enjoyed it more.

6th April Quite the most important event of the day was a letter from you, dated

June 29th, & the first I have had. What a grand letter if it had only been

three words it would have been the most important event of the year, but there so not

a word wasted in the two pages ( I almost know them off by heart by now). It is wonderful

to know that you are all safe & well, & that you are reasonably comfortably settled in

spite of the many obvious difficulties that you make no mention of. It is maddening

that you should be slaving away working your fingers to the bone while all the

time I am hard put to it to fill my days gleefully. I have ceased worrying about

the futility of it all & merely accept this fact. I almost wish I had run away at

the last minute like a cad. The lists of names of people for whom there are letters

but of whom nothing is known, remind us again of the dreadful losses there were

among those - mostly women - who left during the last few days.

Finished the day by having a pound of fresh liver between four of us. xxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx & I cooked it in the lab after lights out ( I have blacked-out the lab).

It was something to dream about for nights to come. I think my cooking was quite a

success though after 14 months abstinence I doubt if my palate is in a fit state to

judge. Dried fish is enough to kill the taste buds in any self respecting mouth.

7th April Another 110 males were today added to this overcrowded rabbit warren

They are mostly Javo, local born but of Iraqi parentage. The were given half an

hour's warning that they were to leave there homes for incarceration. Some of

them had jobs in schools & offices, & why they have been shut up the Nips, alone

know. We have received a promise that no more will be sent in here, which I

suppose means that we shall soon have 2 or 300 more.

10th April Was interviewed by a Nip Army Doctor about Malaria control

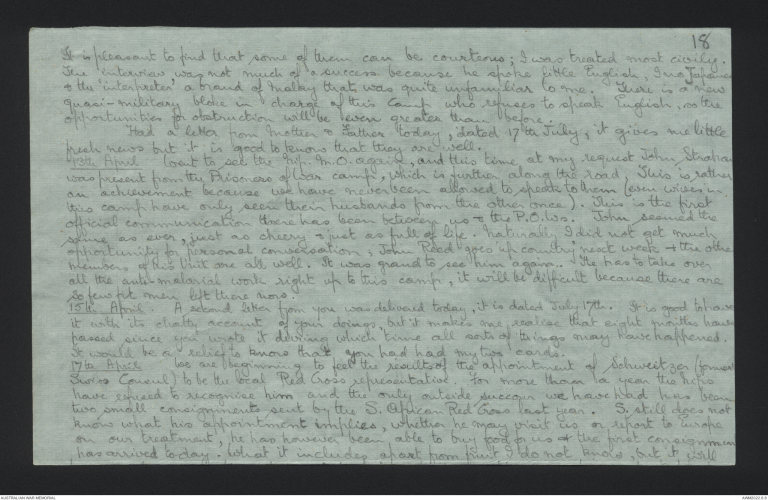

It is pleasant to find that some of them can be courteous; I was treated most civilly.

The interview, was not much of a success because he spoke little English, I no Japanese

& the 'interpreter' a brand of Malay that was quite unfamiliar to me. There is a new

quasi-military bloke in charge of this camp who refuses to speak English, [?] they

opportunities for obstruction will be even greater than before.

Had a letter from Mother & Father today, dated 17th July, it gives me little

rest news but it is good to know that they are well.

13th April Went to see the Nip M.O. again, and this time at my request John Strahan

was present from the Prisoners of War camp, which is further along the road. This is rather

an achievement because we have never been allowed to speak to them (even wives in

this camp have only seen their husbands from the other once). This is the first

official communication there has been between us & the P.O.W.'s. John seemed the

same as ever, just as cheery - just as full of life. Naturally I did not get much

opportunity for personal conversation, John Reed goes up country next week - the other

members of his Unit are all well. It was grand to see him again. He has to take over

all the anti-malarial wok right up to this camp, it will be difficult because there are

so few fit men left there now.

15th April A second letter from you was delivered today, it is dated July 17th. It is so good to have

it with its chatty account of your doings, but it makes one realise that eight months have

passed since you wrote it during which time all sorts of things may have happened.

It would be a relief to know that you had had my two cards.

17th April We are beginning to feel the results of the appointment of Schweitzer ([?]

Swiss Consul) to be the local Red Cross representative. For more than a year the Nips

have refused to recognise him and the only outside succour we have had has been

two small consignments sent by the S. African Red Cross last year. S. still does not

know what his appointment implies, whether he may visit us or report to Europe

on our treatment, he has however been able to buy food for us & the first consignment

has arrived today. What it includes apart from fruit, I do not know, but it will

Sam scott

Sam scottThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.