Papers written by Hodgkin, Ernest P. (Doctor, b.1908 - d.1998) - Part 4

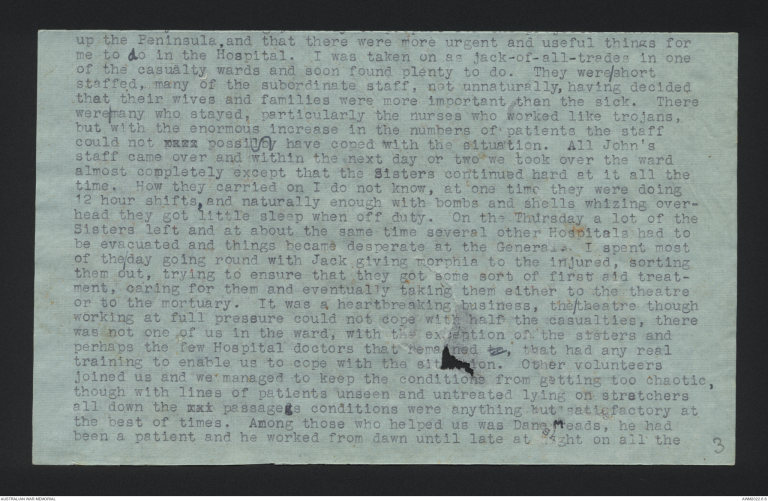

up the Peninsula, and that there were more urgent and useful things for

me to do in the hospital. I was taken on as jack-of-all-trades in one

of the casualty wards and soon found plenty to do. They were/short

staffed, many of the subordinate staff, not unnaturally, having decided

that their wives and families were more important than the sick. There

were/many who stayed, particularly the nurses who worked like trojans,

but with the enormous increase in the numbers of patients the staff

could not prco possilbly have coped with the situation. All John's

staff came over and within the next day or two we took over the ward

almost completely except that the sSisters continued hard at it all the

time. How they carried on I do not know, at one time they were doing

12 hour shifts, and naturally with bombs and shells whizing overhead

they got little sleep when they were off duty. On the Thursday a lot of the

Sisters left and at about the same time several other Hospitals had to

be evacuated and things became desperate at the Generals. I spent most

of the/day going round with Jack giving morphia to the injured, sorting

them out, trying to ensure that they got some sort of first aid treatment,

caring for them and eventually taking them either to the theatre

or to the mortuary. It was a heartbreaking business, the/theatre

though working at full pressure could not cope with half the casualties; there

was not one of us in the ward, with the exception of the sisters and

perhaps the few Hospital doctors that remained to, that had any real

training to enable us to cope with the situation. Other volunteers

joined us and we managed to keep the conditions from getting too chaotic,

though with lines of patients unseen and untreated lying on stretchers

all down the mai passagegs conditions were anything but satisfactory at

the best of times. Among those who helped us was Dane Meads, he had

been a patient and he worked from dawn until late at night on all the

[*3*]

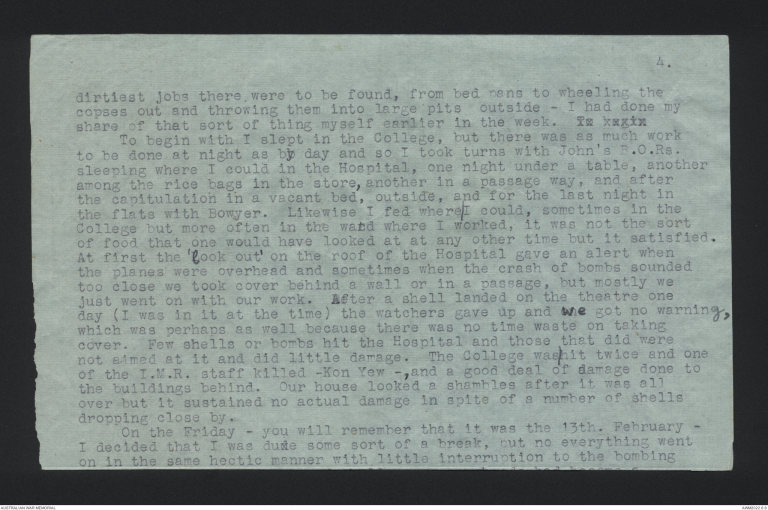

4.

dirtiest jobs there were to be found, from bed pans to wheeling the

copses out and throwing them into large pits outside - I had done my

share of that sort of thing myself earlier in the week. To begin

To begin with I slept in the College, but there was as much work

to be done at night as bby day and so I took turns with John's R.O.Rs.

sleeping where I could in the Hospital, one night under a table, another

among the rice bags in the store, another in a passage way, and after

the capitulation in a vacant bed, outside, and for the last night in

the flats with Bowyer. Likewise I fed where/I could, sometimes in the

College but more often in the ward where I worked, it was not the sort

of food that one would have looked at at any other time but it satisfied.

At first the 'Llook out' on the roof of the Hospital gave an alert when

the planes were overhead and sometimes when the crash of bombs sounded

too close we took cover behind a wall or in a passage, but mostly we

just went on with our work. aAofter a shell landed on the theatre one

day (I was in it at the time) the watchers gave up and [[on?]]we got no warning,

which was perhaps as well because there was no time waste on taking

cover. Few shells or bombs hit the Hospital and those that did were

not aimed at it and did little damage. The College was/hit twice and one

of the I.M.R. staff killed -Kon Yew -,and a good deal of sdamage done to

the buildings behind. Our house looked a shambles after it was all

over but it sustained no actual damage in spite of a number of shells

dropping close by.

On Friday - you will remember that it was the 13th. February -

I decided that I was dude some sort of a break, but no everything went

on in the same hectic manner with little interruption to the bombing

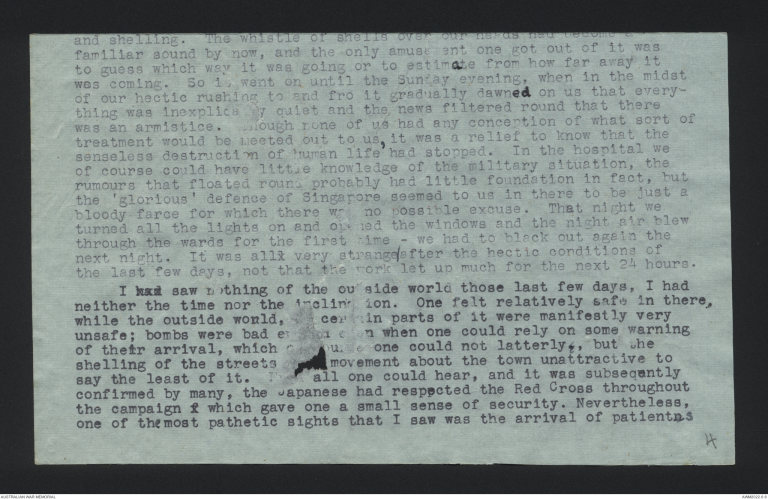

and shelling. The whistle of shells over our heads had become a

familiar sound by now, and the only amusement one got out of it was

to guess which way it was going or to estimeate from how far away it

was coming. So it went on until the Sunday evening, when in the midst

of our hectic rushing to and fro it gradually dawned on us that everything

was inexplicably quiet and the news filtered round that there

was an armistice. Although none of us had any conception of what sort of

treatment would be meeted out to us, it was a relief to know that the

senseless destruction of human life had stopped. In the hospital we

of course could have little knowledge of the military situation, the

rumours that floated round probably had little foundation in fact, but

the 'glorious' defence of Singapore seemed to us in there to be just a

bloody farce for which there was no possible excuse. That night we

turned all the lights on and opened the windows and the night air blew

through the wards for the first time - we had to black out again the

next night. It was alll very strange/after the hectic conditions of

the last few days, not that the work let up much for the next 24 hours.

I had saw nothing of the outside world those last few days, I had

neither the time nor the inclination. One felt relatively safe in there,

while the outside world, [[or?]] certain parts of it were manifestly very

unsafe; bombs were bad enough even when one could rely on some warning

of their arrival, which [[of course?]] one could not latterly., but the

shelling of the streets [[made?]] movement about the town unattractive to

say the least of it. From all one could hear, and it was subsequently

confirmed by many, the Japanese had respected the Red Cross throughout

the campaign f which gave one a small sense of security. Nevertheless,

one of the most pathetic sights that I saw was the arrival of patientns

[*4*]

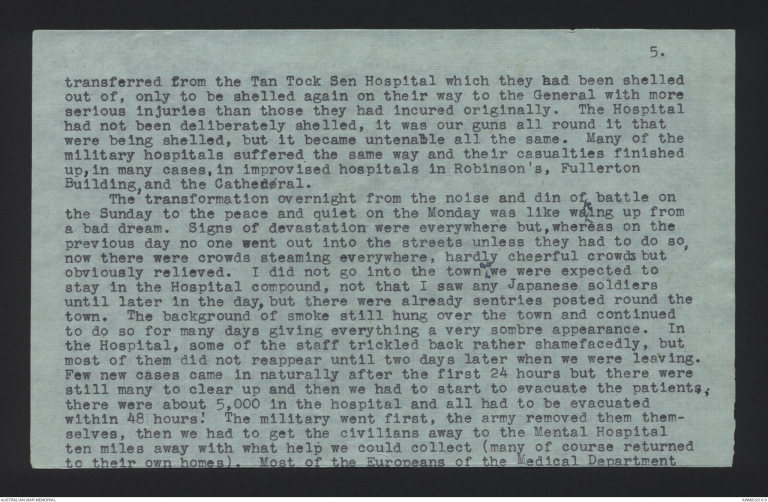

5.

transferred from the Tan Tock Sen Hospital which they had been shelled

out of, only to be shelled again on their way to the General with more

serious injuries than those they had incured originally. The Hospital

had not been deliberately shelled, it was our guns all round it that

were being shelled, but it became untenable all the same. Many of the

military hospitals suffered the same way and their casualties finished

up, in many cases, in improvised hospitals in Robinson's, Fullerton

Building, and the Catherderal.

The transformation overnight from the noise and din of battle on

the Sunday to the peace and quiet on the Monday was like wa^king up from

a bad dream. Signs of devastation were everywhere but, whereas on the

previous day no one ewent out into the streets unless they had to do so,

now there were crowds steaming everywhere, hardly cheerful crowd^s but

obviously relieved. I did not go into the town^as we were expected to

stay in the Hospital compound, not that I saw any Japanese soldiers

until later in the day, but there were already sentries posted round the

town. The background of smoke still hung over the town and continued

to do so for many days giving everything a very sombre appearance. In

the Hospital, some of the staff trickled back rather shamefacedly, but

most of them did not reappear until two days later when we were leaving.

Few new cases came in naturally after the first 24 hours but there were

still many to clear up and then we had to start to evacuate the patients;

there were about 5,000 in the hospital and all had to be evacuated

within 48 hours! The military went first, the army removed them themselves,

then we had to get the civilians away to the Mental Hospital

ten miles away with what help we could collect (many of course returned

to their own homes). Most of the Europeans of the Medical Department

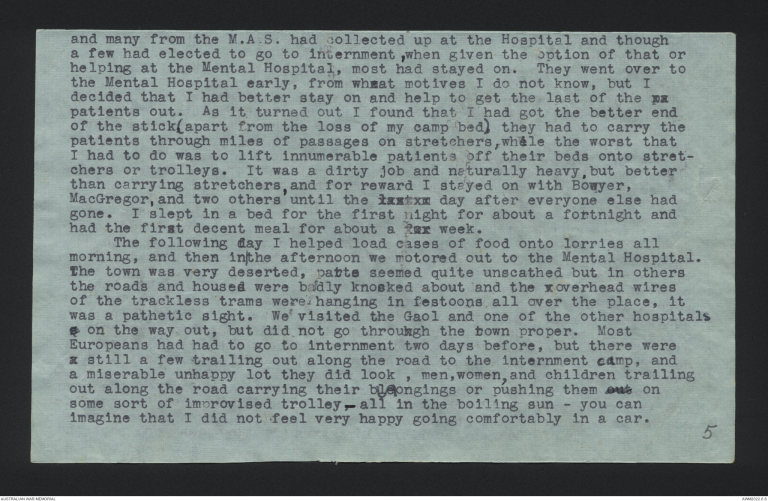

and many from the M.A.S. had collected up at the Hospital and though

a few had elected to go to internment ,when given the option of that or

helping at the Mental Hospital, most had stayed on. They went over to

the Mental Hospital early, from wheat motives I do not know, but I

decided that I had better stay on and help to get the last of the pa

patients out. As it turned out I found that I had got the better end

of the stick,(apart from the loss of my camp bed) they had to carry the

patients through miles of passages on stretchers , wheile the worst that

I had to do was to lift innumerable patients off their beds onto stretchers

or trolleys. It was a dirty job and naturally heavy , but better

than carrying stretchers, and for reward I stayed on with Boewyer,

MacGregor, and two others until the last a day after everyone else had

gone. I slept in a bed for the first night for about a fortnight and

had the firast decent meal for about a for week.

The following fday I helped load cases of food onto Iorries all

morning, and then in/the afternoon we motored out to the Mental Hospital.tThe town was very deserted, patrtes seemed quite unscathed but in others

the roads and houses were badly knoscked about and the v overhead wires

of the trackless trams were hanging in festoons all over the place, it

was a pathetic sight. We visited the Gaol and one of the other hospitalss on the way out, but did not go throuhgh the rtown proper. Most

Europeans had had to go to internment two days before, but there werea still a few trailing out along the road to the internment [[??]]camp, and

a miserable unhappy lot they did look , men, women, and children trailing

out along the road carrying their bleongings or pushing them out on

some sort of improvised trolley,-all in the boiling sun - you can

imagine that I did not feel very happy going comfortably in a car.

[*5*]

6.

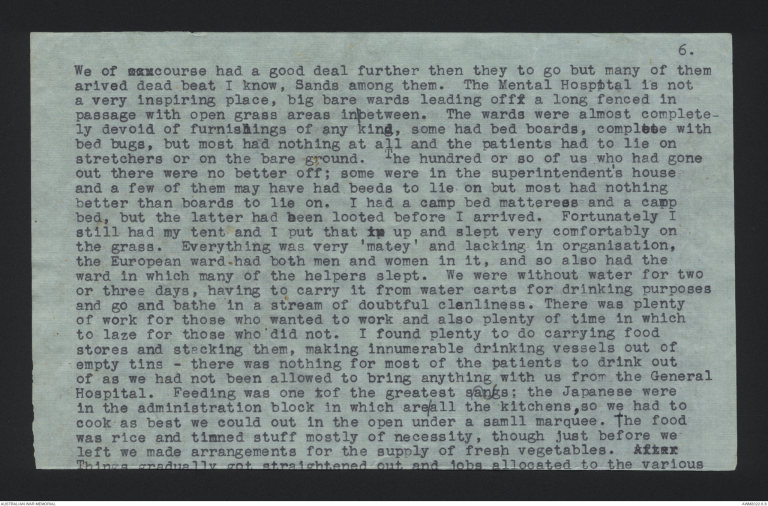

We of ocncourse had a good deal further then they to go but many of them

arived dead beat I know, Sands among them. The Mental Hospoital is not

a very inspiring place, big bare wards leading offf a long fenced in

passage with open grass areas in/between. The wards were almost completely

devoid of furnisihings of any kingd, some had bed boards, compltete with

bed bugs, but most had nothing at all and the patients had to lie on

stretchers or on the bare ground. The hundred or so of us who had gone

out there were no better off; some were in the superintendent's house

and a few of them may have had beeds to lie on but most had nothing

better than boards to lie on. I had a camp bed mattereess and a capmp

bed, but the latter had sbeen looted before I arrived. Fortunately I

still had my tent and I put that in up and slept very comfortably on

the grass. Everything was very 'matey' and lacking in organisation,

the European ward had both men and women in it, and so also had the

ward in which many of the helpers slept. We were without water for two

or three days, having to carry it from water carts for drinking purposes

and go and bathe in a stream of doubtful claenliness. There was plenty

of work for those who wanted to work and also plenty of time in which

to laze for those who did not. I found plenty to do carrying food

stores and stacking them, making innumerable drinking vessels out of

empty tins - there was nothing for most of the patients to drink out

of as we had not been allowed to bring anything with us from the General

Hospital. Feeding was one tof the greatest sangs; the Japanese were

in the administration block in which are/all the kitchens ,so we had to

cook as best we could out in the open under a samll marquee. The food

was rice and timnned stuff mostly of necessity, though just before we

left we made arrangements for the supply of fresh vegetables. After

Things gradually got straightened out and jobs allocated to the various

people who were there, though as it turned otu out the scheme never

went into operation.

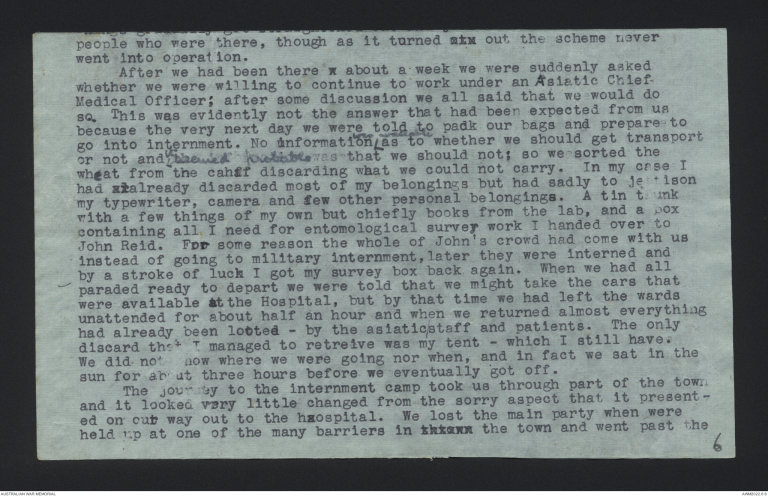

After we had been there w about a week we were suddenly asked

whether we were willing to continue to work under an Asiatic Chief

Medical Officer; after come discussion we all said that we would do

so. This was evidently not the answer that had been expected from us

because the very next day we were told to padck our bags and prepare to

go into internment. No uinformation ^was available as to whether we should get transport

or not and ^ [[it seemed probable?]] was that we should not; so we sorted the

wheat from the cahaff discarding wahat we could not carry. In my case l

had srlalready discarded most of my belongings but had sadly to jettison

my typewriter, camera and afew other personal belongingas. A tin trunk

with a few things of my own but chiefly books from the lab, and a box

containing all I need for entomological survery work I handed over to

John Reid. Froor some reason the whole of John's crowd had come with us

instead of going to military internment, later they were interned and

by a stroke of luchk I got my survey box back again. When we had all

paraded ready to depart we were told that we might take the cars that

were available tat the Hospital, but by that time we had left the wards

unattended for about half an hour and when we returned almost everything

had already been lototed - by the asiatic/staff and patients. The only

I managed to retreive vas my tent - chich I still have.

discard that I managed to retrieve was my tent - which I still have.

We did not know where we were going nor when, and in fact we sat in the

sun for about three hours before we eventually got off.

The journey to the internment camp took us through part of the town

and it looked very little changed from the sorry aspect that it presented

on outr way out to the haospital. We lost the main party when were

held up at one of the many barriers in thtown the town and went past the

[*6*]

7.

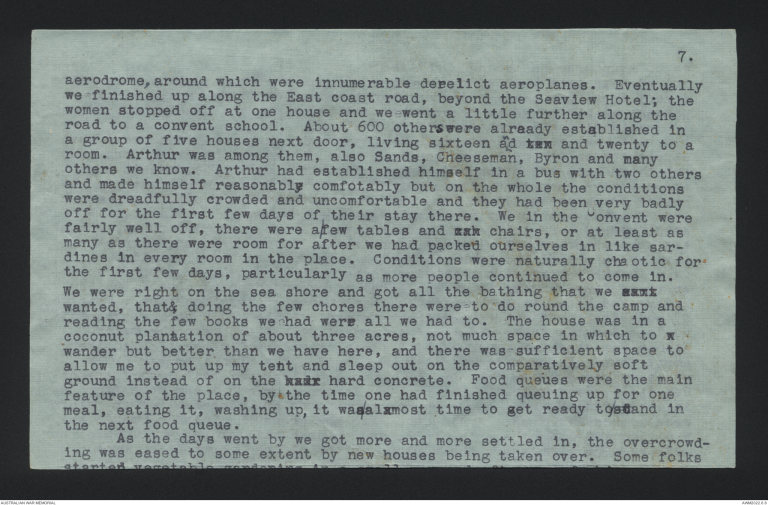

aerodrome, around which were innumerable deerelict aeroplanes. Eventually

we finished up along the East coast road, beyond the Seaview Hotel; the

women stopped off at one house and we went a little further along the

road to a convent school. About 600 others awere alraeady estqablished in

a group of five houses next door, living sixteen a^nd ten and twenty to a

room. Arthur was among them, also Sands, Cheeseman, Byron and many

others we know. Arthur had established himself in a bus with two others

and made himself reasonabley comfotably but on the whole the conditions

were dreadfully crowded and uncomfortable and they had been very badly

off for the first few days of their stay there. We in the Convent were

fairly well off, there were a/few tables and cah chairs, or at least as

many as there were room for after we had packed ourselves in like sardines

in every room in the place. Conditions were naturally cha otic for

the first few days, particularly as more people continued to come in.

We were right on the sea shore and got all the bathing that we want

wanted, that&, doing the few chores there were to do round the camp and

reading the few books we had werre all we had to. The house was in a

coconut planatation of about three acres, not much space in which to w

wander but better than we have here, and there was sufficient space to

allow me to put up my tetnt and sleep out on the comparatively soft

ground instead of on the hadr hard concrete. Food queues were the main

feature of the place, by the time one had finished queuing up for one

meal, eating it, washing up, it waas/alamost time to sget ready to/sdtand in

the next food queue.

As the days went by we got more and more settled in, the overcrowding

was eased to some extent by new houses being taken over. Some folks

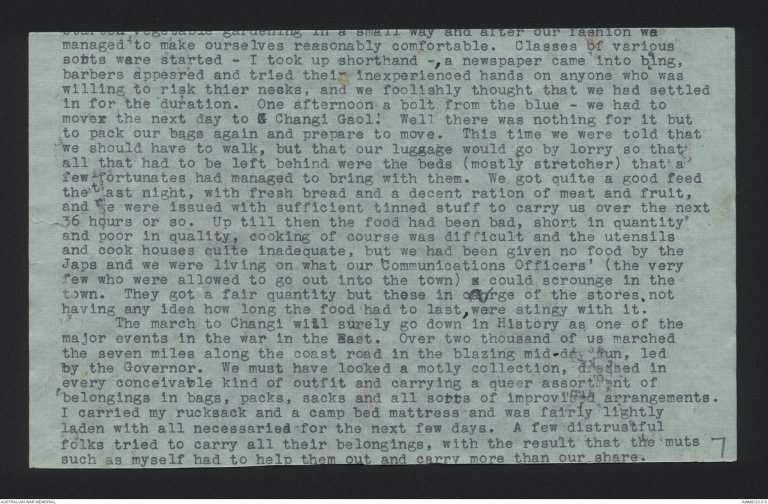

started vegetable gardening in a small way and after our fashion wae

managed'to make ourselves reasonably comfortable. Classes of various

sotrts waere started - I took up shorthand -,a newspaper came into b^eing,

barbers appeared and tried their inexperienced hands on anyone who was

willing to risk thier nescks, and we foolishly thought that we had settled

in for the duration. One afternoon a bolt from the blue - we had to

movexr the next day to G Changi Gaol! Well there was nothing for it but

to pack our bags again and prepare to move. This time we were told that

we should have to walk, but that our lugsgage would go by lorry so that

all that had to be left behind were the beds (mostly stretcher) that a

few fortunates had managed to bring with them. We got quite a good feed

the last night, with fresh bread and a decent ration of meat and fruit,

and we were issued with sufficient tinned stuff to carry us over the next

36 hours or so. Up till then the food had been bad, short in quantity

and poor in quality, cooking of course was difficult and the utensils

and cook houses quite inadequate, but we had been given no food by the

Japs and we were living on what our 'Communications Officers' (the very

few who were allowed to go out into the town) s could scrounge in the

town. They got a fair quantity but theose in cahrge of the stores, not

having any idea how long the food had to last,were stingy with it.

The march to Changi wiill surely go down in History as one of the

major events in the war in the eEast. Over two thousand of us marched

the seven miles along the coast road in the blazing mid-day sun, led

by the Governor. We must have looked a motly collection, dressed in

every conceivavble kind of outfit and carrying a queer assortment of

belongings in bags, packs, sacks and all sotrts of improvised arrangements.

I carried my rucksack and a camp bed mattress and was fairly lightly

laden with all necessariesd for the next few days. A few distrustful

folks tried to carry all their belongings, with the result that the muts

such as myself had to help them out and carry more than our share.

[*7*]

8.

[*CHANGI*]

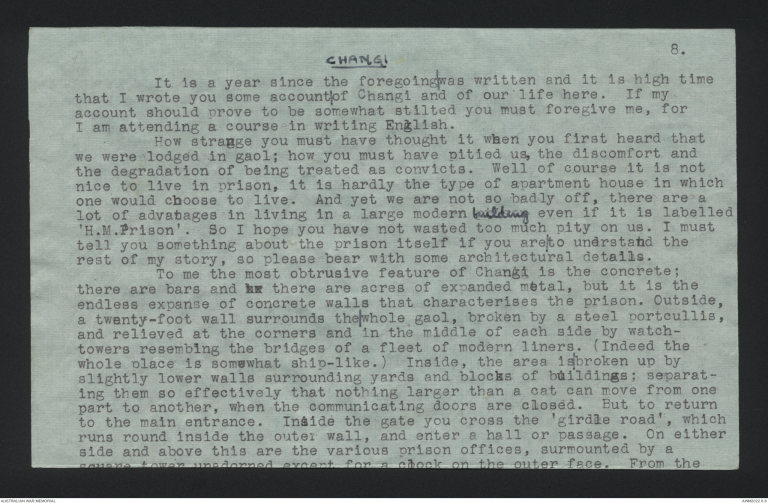

It is a year since the foregoing/was written and it is high time

that I wrote you some account/of Changi and of our life here. If my

account should prove to be somewhat stilted you must foregive me, for

I am attending a course in writing Enlglish.

How stragnge you must have thought it wehen you first heard that

we were lodged in gaol; how you must have pitied us, the discomfort and

the degradation of being treated as convicts. Well of course it is not

nice to live in prison, it is hardly the type of apartment house in which

one would cohoose to live. And yet we are not so badly off, there are a

lot of advantages in living in a large modern building even if it is labelled

'H.M. 'Prison'. So I hope you have not wasted too much pity on us. I must

tell you something about the prison itself if you are/to undrstatnd the

rest of my story, so please bear with some architectural detaisls.

To me the most obtrusive feature of Chaniggi is the concrete;

there are bars and he there are acres of expanded mtetal, but it is the

endless expanse of concrete walls that characterises the prison. Outside,

a twenty-foot wall surrounds the/whole gaol, broken by a steel portcullis,

and relieved at the corners and in the middle of each side by watchtowers

resembilng the bridges of a fleet of modern liners. (Indeed the

whole place is somwewhat ship-like.) Inside, the area is/broken up by

slightly lower walls surrounding yards and blocsks of biuildinsgs; separating

them so effectively that nothing larger than a cat can move from one

part to another, when the communicating doors are colosed. But to return

to the main entrance. Iniside the gate you cross the 'girdele road', which

runs round inside the outer wall, and enter a hall or passage. On either

side and above this are the various prison offices, surmounted by a

square tower unadorned except for a colock on the outer face. From the

Sam scott

Sam scottThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.