Papers written by Hodgkin, Ernest P. (Doctor, b.1908 - d.1998) - Part 13

[*71*]

cannot maintainit itself on the steeper slopes which are & dusty green or

bure and brown. On the southern face the sun does not touch the cliffs

and they are black slashes against the sage, of the slopes.

(sample of military language from todays's orders: Medical history

cards WILL be completed before personnel are allowed to disembark. A

notice on the deck says 'Chairs will be returned to the lounge after use -

an entirely erronous statement.)

Sunday 7th. Oct. The scene was still the same when I woke this morning,

very lovely but one can have too much of a good thing. It was a pleasant

cahnge when after breakfast we ran into Bowen I think. They varied in size

from one that must have been at leat twenty miles long to rocks no bigger

than a house. Through the maze of channels we steered a tortuous sourse,

at one moment sailing straight for a hundred-foot cliff xxx only to swerve

sharply and forge ahead in quite a different direction just when it seemed

we must run ashore. X One channel was called Whitsunday Channel. I suppose

that nowhere were we less than a mile from the land but from sixty feet

above the water it looked as though one could throw a stone ashore. Some

of the islands were very lovely, steep, grass or shrub-covered hill sides

with fir-like trees, rocks, and little sandy bays, set in a jade sea.

Someone had built a bungalow on the prettiest and ther were people there to

wave to us. That was almost the first sign of life we had seen. It must

be a wonderful place for yachting; sheltered water, an infinity xx of safe

anchorages, plenty of fresh water, bathing and camping places. The only

apparent snag was the tide rips that tore the water round many of the headlands.

Whales might be uncomfortable neighbours in a small boat; for a long

time we watched one coming up to blow and frolic a mile or so from the ship

The weather has been brilliant, scarcely a cloud in the sky. A

breeze strong enough to take the bite from the fierce sun and to make the

air quite chilly out of the sun; for the first time I have felt I needed a

shirt during the day. Sleeping on deck I am glad of a woollen blanket. over

two nights ego I hastily pulled a second blanket over me, overas and two nights ago I hastily pulled a second blanket over me when a

change of course brought a gale chasing down the deck and threatening to

blow me overboard. Thank goodness it has been calm -so far. The worst we

have had was a slight pitch one day and the for the rest one would not know

one was in a|ship at all save for the swish of the water and the xxxx throb

of the engines.

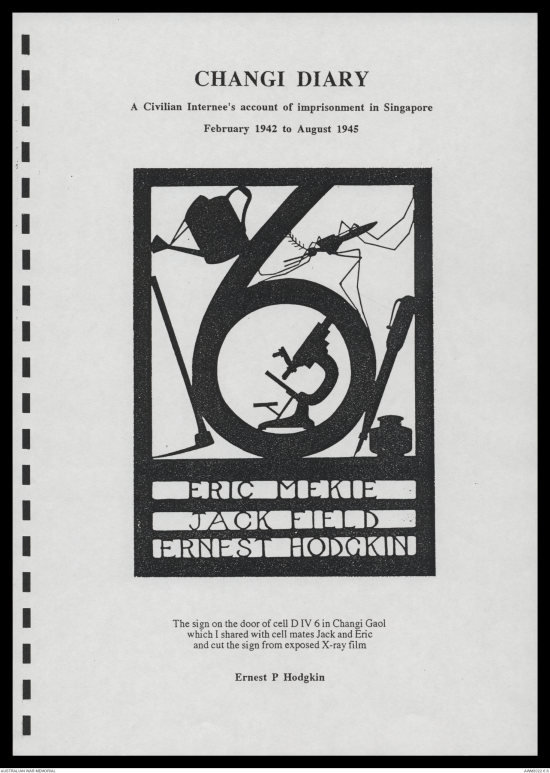

CHANGI DIARY

A Civilian Internee's account of imprisonment in Singapore

February 1942 to August 1945

Diagram – see original document.

ERIC MEKIE

JACK FIELD

ERNEST HODGKIN

The sign on the door of cell DIV 6 in Changi Gaol

which I shared with cell mates Jack and Eric

and cut the sign from exposed X-ray film

Ernest P Hodgkin

{{PB}}

INTRODUCTION

The Diary

This diary was written during internment following the capitulation

of Singapore to the Japanese army on 15 February 1942. It was written in the

form of a letter to my wife, Mary, who had been evacuated to Perth early in

January 1942 with our four children. It never occurred to me that nearly

four years would elapse before the letter could be delivered, or that it would

grow to some 56,000 words, most of it written in pencil, close-spaced but neat,

on 70 pages of blue quarto notepaper.

The early part of the diary tells the story of the fall of Singapore as

seen from the relative safety of the General Hospital, of our incarceration in

Changi Gaol, and of our life there. From April 1943 it became more a diary of

events, of rumour replacing news, the routine of prison life as I saw it,

cultural activities, snippets of philosophising, and repetitive comments on

food or the lack of it. The first part of the diary ended abruptly following the

'Double Tenth' (10th October 1943), and was not resumed until Christmas of

that year when I/we had got over the shock of that fateful day.

In May 1944, the move from the enclosing high grey walls of Changi

Gaol to the relative freedom of Sime Road Camp in the middle of Singapore

Island was most welcome. However it made little difference to the routine of

life and signalled a progressive decline in nutrition which was only reversed

during the phoney internment period which followed news of the Emperor's

capitulation in Japan on 15 August 1945 and the gradual British takeover,

with the surrender of the Japanese forces in Singapore on 12 September.

The diary ends with evacuation to Australia and purple passages

about the beauty of the Great Barrier Reef islands as seen from the deck of a

troop ship as it approached Brisbane. There GPO staff helped me to phone

Mary in Perth, not easy at that time. Then on to Sydney where Friends

(Quakers) cared for me for three days before the two-day flight with other

internees in a RAF DC3, to reunion with my family on the tarmac of Perth

airport on Sunday 15 October 1945.

Soon after my return a neighbour typed the first part of the diary,

but the second part remained unread, in manuscript, until 1995 when

Elizabeth Frowde read it and kindly offered to type it at her home in England

during her Christmas holidays - what a holiday. She knew people mentioned

in the diary and was interested in our experiences as Civilian Internees. Her

Father, Robert Jagoe, had been a POW, in the Changi Camp.

Our two families were friends, we shared holiday bungalows at Port

Dickson on the west coast, and the friendship continued when the wives and

children were evacuated to Perth. After war ended in Europe the Jagoe family

returned 'Home' to England, as did many others, but Perth had become home

for the Hodgkin family and Mary refused to return to England. So it was to

Australia that I was 'repatriated' and in due course became an Australian

Citizen. My great regret is the loss of contact with the many friends named

in the diary who returned to England and later to their jobs in Malaya.

I have done a minimum of editing and added a few explanatory notes

in square brackets, necessary after the fifty-year gap. If the language seems

florid at times, please remember I was reading avidly in good literature and

being coached in writing English. The following brief personal history may

help readers who are unfamiliar with my background.

Background to internment

At the time of my internment I was a British Colonial Government

Servant employed at the Institute for Medical Research (IMR) in Kuala

Lumpur where for eleven years I was the Medical Entomologist. My job was

to study the mosquitoes and other arthropods that transmit malaria and other

tropical diseases in cooperation with other IMR staff. It was an interesting

job which I enjoyed and would have liked to have returned to after the war.

Mary and I were happy in Malaya it was our home, though of course HOME

meant England to most of us expatriates, only the prospect of separation from

our four children when they reached secondary school age worried us.

Appointment to Malaya came more by accident than intent. I had

graduated from Manchester University and been engaged to fellow student

Mary McKerrow for two years. We wanted to get married. There was little

prospect of a job in England in 1930, but we had no aversion to going

overseas. A two-year scholarship to the Imperial College of Tropical

Agriculture in Trinidad was rejected: wives were not allowed. Appointed to a

junior position in Kenya, I was sent to the London School of Hygiene and

Tropical Medicine (LSH&TM) where two famous entomologists, P A Buxton and

V B Wigglesworth, introduced me to medical entomology, and became good

friends. After my three months there, the senior man from Kenya reneged

on his appointment to Kuala Lumpur, and the Colonial Office offered the job

to new-boy — me. I found Malaya on the map, accepted the job and another

month at LSH&TM, married, and set sail for Malaya in February 1931.

Mary followed four months later when she had finished her Teacher's Diploma.

At the IMR I was a lone hand, with no experience and little direction

on the line of research to follow, but guided by Jack Field (Malaria Research

Officer) with whom I had a productive cooperation and happy friendship,

there and in Changi. My principal line of research was the transmission

of malaria by mosquitoes, and measures for their control, but also involved

other diseases: dengue, filariasis, tropical typhus, and the fleas, mites and

ticks that carry them. This took me all over the Peninsula and brought me in

contact with both Government and plantation Health and Medical officers.

When I visited KL in 1993 I was taken by my first Malayan student, now a

well-known Doctor, to visit the IMR and was intrigued to find my old

laboratory still in use and now a designated Heritage building.

Mary's involvement with Girl Guides brought us into the circle of

Guide and Scout leaders who became close friends, and soon I found myself

involved in Scouting. While on sabbatical leave in 1939, I represented Malaya

at the International Rover Scout Moot at Crief in Scotland only weeks before

Hitler invaded Poland. We sailed before Christmas and back in KL life and

work continued more or less normally until the threat of invasion brought

British and Australian troops; some became regular visitors to our home. For

a short time I was an incompetent Sargeant in charge of an ambulance in the

Volunteers — a sort of Dad's Army experience.

The disaster of Pearl Harbour on 7 December 1941, landings in

Kelantan, and the sinking of the Repulse and Prince of Wales three days later

brought the reality of war to our doorstep. The rapid advance of Japanese

forces down the Peninsula forced us to retreat from Kuala Lumpur to

Singapore just after Christmas. We occupied a vacant house in the compound

of the College of Medicine overlooking the docks, a target for the bombers. On

17th January Mary and the children: Graham (9) Patricia (8), Jonathan (4)

and Michael nearly 2, sailed for Perth. The ship was overcrowded and it was

an uncomfortable journey, but it was not harassed by enemy ships or planes

and soon a cable confirmed their safe arrival. There the diary takes over.

Early life

I was born in 1908 and the first three years of life were in

Madagascar where my parents were Quaker missionaries stationed in a small

town 100 km west of the capital, Tananarive. There I probably had my only

personal encounter with the malaria parasite, Plasmodium, which took the

lives of three siblings. After their 'leave' in Ireland where sister Erica was

born (Mother was Irish) and in England (Father was English), my parents

returned to Madagascar in 1912 taking Erica with them. For most of the

next seven years I was fortunate to share a happy family life with close cousins in

Darlington, England. But as the diary relates, I have never wished to inflict

such separation on my children. With the end of the war, my parents

returned to England and for me there followed six years between home and a

Quaker co-educational boarding school, Sidcot School on the end of the

Mendip Hills in Somerset, where I indulged a passion for natural history and

explored the lovely countryside by bicycle. Then a year at Leeds University

and three at Manchester, graduating with a BSc in Zoology and Entomology,

and a fiancée, before starting life in Malaya.

Return to civilisation

Rehabilitation into family life and acclimatisation to Australia were

swift and easy: "we seem to have gone on just where we left off" is the

comment in a letter written to my parents a week after my return. Picnics in

the hills with family friends, introduction to the abundant wildflowers, and

acceptance into the Quaker fellowship all helped. I don't think internment

left any permanent scars, but it certainly re-oriented my life. From 1946, a

temporary lectureship in Zoology at the University of Western Australia —

which I suspect Mary had engineered — continued under various titles for 28

years. That was followed by 16 years 'part-time' work for the Environmental

Protection Authority on environmental problems of estuaries of the south

west, and now in 'retirement' a continuing involvement in estuarine studies.

The decision to abandon my job in Malaya was difficult, though

probably never really in doubt because it would again have involved

separation from the family. It was made easier by friendship with the

Professor of Zoology and an entertaining week of field work on Rottnest

Island with him, his staff and students — my induction into Australian

university mores. He gave me the facilities of his Department to finish, and

publish, the 'keys' to the Anopheles of Malaya which I had worked on in

Singapore. Later, there were two more papers on mosquitoes and malaria, and

a brief brush with mosquitoes in northern WA, and with fleas and urban

typhus in Perth. But my career as a medical entomologist really ended in 1950

with a thesis, The Transmission of Malaria in Malaya, which gained me the

degree of DSc from the University of Western Australia, and the 'Doctor' label

necessary for an Academic.

When the children grew up Mary returned to study, and an MA In

Anthropology, then was a popular lecturer in Asian studies at UWA. For many

years we kept contact with Malaya while she cared for the welfare of Asian

students. Twice when on leave, we returned to Malaya to visit former students

for her to interview them for the two books she wrote: Australian Training

and Asian Living (1966) and The Innovators (1972). Sadly, after retiring,

Mary died of a stroke in 1985. Now, after fifty-five years here, our family

scores: the four children with their spouses, fourteen grandchildren with

nine spouses, and eighteen great-grandchildren, most still in Australia.

THE SIEGE OF SINGAPORE

26th. April, 1942.

I decided I would not do as so many others are doing and keep a diary

because I am not anxious to remember the happenings of the last few weeks; on the other hand

I know that you will want to know all about it. So before all the events surrounding the fall of Singapore quite go from my memory l will try to record them and the happenings of the

subsequent weeks as they affected me. I do not suppose that the political events interest you particularly, and in any case they are probably best omitted from what may at some time have to

be censored.

You may possibly have heard something of my doings after you left from Elsie Field

or Mrs. Shelley, but very little I expect. They went at the end of January and until then I

continued to live with the Shelleys at College Road, next to the College of Medicine. At this

distance of time there is nothing that stands out particularly during those weeks; I worked hard,

chiefly at a new edition of my Keys for identifying Anopheles mosquitoes, went out in the field

a certain amount with John Strahan's Malaria Unit, but apart from that hung about the house

and College mostly — there was nothing to take me away. As it seemed at the time things got

rather hot there; there was a good deal of bombing on either side and one or two came most

uncomfortably close, but no one in the house was ever hurt. Nevertheless I was very thankful

you got away when you did as the kids would have been very frightened on one or two

occasions.

Things gradually became more and more difficult; green vegetables became quite

unobtainable, the bread failed for a few days, and I know Mrs Shelley had a pretty difficult

time doing the shopping. But although of course we continued to camp out we never really

wanted for anything important. Dr. Faris, in whose house we were, continued to denude the

house of all his furniture, and a bomb at the foot of the bank in front of the house finally

removed all the blackout material; if the bank had not been there the bomb must have done

much more serious damage. We made a very efficient shelter inside the front door with sand

bags and the dining room table, we filled the sand bags from one of the bunkers on the golf

course and I carried them up the hill — hard labour!

I found the Shelleys good company, though needless to say I would have liked to

spank the children quite often. Ginger and Spike both turned up to say good bye to you soon

after you had gone, and if I remember rightly I saw Gorge Tice once or twice. I suppose he got

away and you may have heard from him. I went to town little, there was little to take me there

except my frantic efforts to get as much money to you as I could before the crash. The town

was not an attractive place during the morning ‘hate’ everyone went to earth during the alerts

whether or not there were any planes about so it was difficult to get anything done. I spent one

raid in company with Dr. Morris in the basement of Whiteaway's shop and then foolishly

returned by the docks only to be caught by another alert — fortunately uneventful. I went to get

enlargements of the photos of the kids that we sent for Christmas, only to find the shop had

disappeared the previous day; so all I have are the ones we sent the Christmas before. Why on

earth I did not give you the camera to take away with you I do not know, but then if I had

known when you went that Singapore would fall there are lots of other things that I would have

given you to take. It is no use crying over spilt milk.

When Elsie and Joan Field and the Shelleys left at the end of January I went to live at

Nassim Road with Jack Field, John Strahan, John Reid and Routley (also in John's unit). John

S. did not stay long but returned to the College so as to be near his men. We got on quite well

together, violent arguments — mostly political — drove me out of the house many evenings, but

generally I found work to do and sometimes went to call on James Cox and Brunt at the end of

the road. It was a delightful place to live in until it became uncomfortably near the front line and

we had to move back to the College. The shelter that Elsie had pinned her faith on was

miserable affair, if there had been the smallest bomb within a hundred yards all the sand bags

1

would have fallen in on her; one of the first things I did was to rebuild it. We also dug a slit

trench in the garden but fortunately never had any real need to use either. We slept downstairs,

all four of us in one room; I thought I was scared of bombs but I could not compete with

Routley who went scuttering for shelter at the least thing. Jack on the other hand, I was

convinced would move too late if anything did come our way! Incidentally I doubt if Elsie and

Joan would ever have got away if he had not been pushed by all his friends. He used to get me

very wild because I could not get him up early in the morning, if he had his own way he was

never ready to leave until the time of the morning alert, in which we were inevitably caught

either at the house or on our way to the College. However by dint of much bullying I

eventually managed to get him away by 7.45 which was rather an achievement.

During the week or more we were at Nassim Road, work at the College was

necessarily rather disturbed. I think the planes must have used the College as a landmark for

letting off their bombs for the docks, anyway they always seemed to come directly overhead

and you could never be quite certain that they would not let their eggs go too soon one time. I

am afraid I got a bit jittery about that time and I found it difficult to settle down to accurate

scientific drawings, in between running up and down stairs to take shelter in the passage or

library. At that time the College was already sheltering a considerable number of people who

either would not or could not live in their own homes, and the passage was fitted up with

bunks complete with bed bugs. Consecutive work was generally possible during the

afternoons, and the evenings were almost always peaceful.

About the middle of that week it must have been that the oil tanks at the Naval Base

were fired, Singapore was already very smoky, but after that an air of gloom hung over the

whole town blotting out the sun and making everything filthy, it was almost like being in

Manchester if it had not been for the contrast of the green grass and trees. The gloom became

worse as the smoke from burning buildings was added to that from the oil tanks, but that was

during the last week. We knew well enough the night the Japs landed on the island, the barrage

was terrific, though it let up towards the morning, the next night was much the same and after

that the sound of bombing and shell fire became almost continuous. Looking back it is

extraordinary to think how normally we carried on in the midst of it all but I cannot say that I

should care to go through it all again, although we were never in any real danger, or at any rate

not then.

It must have been about the 10th February that we left Nassim Road; for the last few

nights there had been occasional shots nearby and no one seemed to know just where the Japs

were. For myself, I did not care to run the risk of waking up one morning to find that I was in

the front line. The fighting was like that, there does not seem to have been a definite line, or if

there was one on our side there were certainly Japs behind it often enough. Jack and John Reid

stayed on a night longer than Routley and myself, but they spent an uncomfortable night and

when they went back later in the day it was to find a platoon stalking a sniper in the trees at the

end of the road. The servants at Nassim Road had been very pleasant and the cook had fed us

amazingly well in spite of the difficulties. By contrast the picnicking at the College was rather a

come down.

The lady who had done the catering at the College had done it very well, but she

pushed off quite without warning and things would have been very difficult if the stewards

from the Empress of Asia had not been billeted on the College. As it was they cooked as best

they could on charcoal stoves in the College itself and for the rest they opened tins so that we

fared very well under the difficult conditions, thanks to the foresight of Dr. Allen who laid up

large stores of food there. The building was very crowded, the subordinate staff with many of

their families camped out in the central passage, the European staff and many hangers on such

as myself occupied the rooms on the ground floor or camped out in the passages or labs, while

the Empress staff lived in several of the larger rooms on the upper floors. Richard Green (of

the I.M.R.) established himself in two rooms on the top floor with a complete set of furniture brought there at the expense of more important things and made himself thoroughly

comfortable and most unpopular.

2

THE GENERAL HOSPITAL

I don't think I can have stayed many nights in the College because I soon discovered

that the Hospital was in desperate need of assistance. I concluded that with the Japs on the

Island it was not much use continuing placidly to prepare for the projected advance up the

Peninsula, and that there were more urgent and useful things for me to do in the hospital. I was

taken on as Jack-of-all-trades and soon found plenty to do. They were short-staffed, many of the

subordinate staff, not unnaturally, having decided that their wives and families were more

important than the sick. There were many who stayed, particularly the nurses who worked like

trojans, but with the enormous increase in the numbers of patients the staff could not possibly

have coped with the situation. All Strahan's staff came over and within the next day or two we

took over the ward completely, except that the sisters continued hard at it all the time. How they

carried on I do not know, at one time they were doing twelve-hour shifts, and naturally with

shells and bombs whizing overhead all the time they got little sleep when they were off duty.

On the Thursday a lot of the sisters left and at about the same time several other

hospitals had to be evacuated and things became desperate at the General. I spent most of the

day going round with Jack Field giving morphia to the injured, sorting them out, trying to

ensure that they got some sort of first aid treatment, caring for them and eventually taking them

either to the theatre or the mortuary. It was a heartbreaking business, the theatre though

working at full pressure could not cope with half the casualties; there wasn't one of us in the

ward, with the exception of the sisters and the few Hospital doctors that remained, that had any

real training to enable us to cope with the situation. Other volunteers joined us and we managed

to keep the conditions from getting too chaotic, though with lines of patients unseen and

untreated lying on stretchers all down the passages conditions were anything but satisfactory at

the best of times. Among those who helped us was Dane Meads, he should have been a patient

and he worked from dawn until late at night on all the dirtiest jobs there were to be found, from

bed pans to wheeling the corpses out and throwing them into large pits outside — I had done my share of that sort of thing earlier in the week.

To begin with I slept in the College, but there was as much work to be done by night

as by day and so I took turns with John's B.O.Rs. sleeping where I could in the Hospital, one

night under a table, another among the rice bags in the store, another in a passage way, and

after the capitulation in a vacant bed outside, and for the last night in the flats with Dr. Bowyer

Likewise I fed where I could, sometimes in the College but more often in the ward where I

worked, it was not the sort of food one would have looked for at any other time but it satisfied.

At first the lookout on the roof of the Hospital gave an alert when the planes were

overhead, and sometimes when the crash of bombs sounded too close we took cover behind a

wall or in a passage, but mostly we just went on with our work. After a shell landed on the

roof of the theatre one day (I was in it at the time) the watchers gave up and we got no warning,

which was perhaps as well because there was no time to waste in taking cover. Few shells or

bombs hit the Hospital and those that did were not aimed at it and did little damage. The

College was hit twice and one of the I.M.R. staff (Kon Yew) was killed, and a good deal of

damage was done to the buildings behind. Our house looked a shambles after it was all over

but it sustained no actual damage in spite of a number of shells dropping close by.

On the Friday — you will remember that it was the 13th February [our wedding

anniversary] — I decided I was due for some sort of a break, but no, everything went on in the

same hectic manner with little interruption to the bombing and shelling. The whistle of shells

over our heads had become a familiar sound by now, and the only amusement one got out of it

was to guess which way a shell was going or to estimate from how far away it was coming. So

it went on until Sunday evening, when in the midst of our hectic rushing to and fro it gradually

dawned on us that everything was inexplicably quiet and the news filtered through that there

was an armistice. Though none of us had any conception of the sort of treatment that would be

meted out to us, it was a relief to know that the senseless destruction of human life had

stopped. In the hospital we of course could have little knowledge of the military situation, the

rumours that floated round probably had little foundation in fact, but the 'glorious' defence of

3

Singapore seemed to us in there to be just a farce for which there was no possible excuse. That

night we turned all the lights on and opened the windows and the night air blew through the

wards for the first time — we had to black out again the next night. It was all very strange after

the hectic conditions of the last few days, not that the work let up very much for the next

twenty-four hours.

I saw nothing of the outside world those last few days. I had neither the time nor

inclination. One felt relatively safe in there while the outside world, or certain parts of it, were

manifestly very unsafe; bombs were bad enough even when one could rely on warning of their

arrival, but the shelling of the streets made movement about the town unattractive to say the

least of it. From all one could hear, and it was subsequently confirmed by many, the Japanese

had respected the red cross throughout the campaign which gave one a small sense of security.

Nevertheless one of the most pathetic sights that I saw was the arrival of patients transferred

from the Tan Tock Sen Hospital which they had been shelled out of, only to be shelled again

on their way to the General, with more serious injuries than those they had sustained originally.

The hospital had not been deliberately shelled it was our guns all round it that were being

shelled, but it became untenable all the same. Many of the military hospitals suffered in the

same way and many of their casualties finished up in improvised hospitals in Robinson's shop,

Fullerton Building and the Cathedral.

EVACUATNG THE HOSPITAL

The transformation overnight from the noise and din of battle on the Sunday to the

peace and quiet on the Monday was like waking up from a bad dream. Signs of devastation

were everywhere, but, whereas on the previous day no one went out into the streets unless they

had to do so, now there were crowds streaming everywhere, hardly cheerful crowds but

obviously relieved. I did not go into the town as we were expected to stay in the Hospital

compound, not that I saw any Japanese soldiers until later in the day, but there were already

sentries posted round the town. The background of smoke still hung over the town and

continued to do so for many days giving everything a very sombre appearance.

In the Hospital some of the staff trickled back shamefacedly, but most of them did not

reappear until two days later when we were leaving. Few new cases came in after the first

twenty-four hours but there were still many to clear up and then we had to start to evacuate the

patients; there were about 5,000 and all had to be evacuated within forty-eight hours. The

military went first, the army removed them themselves, then we had to get the civilians away to

the Mental Hospital ten miles away with what help we could collect (many of course returned to

their own homes). Most of the Europeans of the Medical Department and many of the M.A.S.

had collected at the hospital and though a few had elected to go to internment, when given the

option of that or helping at the Mental Hospital, most had stayed on. They went over to the

Mental Hospital early, from what motives I do not know, but I decided that I had better stay on

and help to get the last of the patients out. As it turned out, I got the better end of the stick

(apart from the loss of my camp bed) they had to carry the patients through miles of passages

on stretchers, while the worst I had to do was to lift innumerable patients off their beds onto

stretchers or trolleys. It was the dirtiest job and naturally heavy, but better than carrying

stretchers and, for reward, I stayed on with Dr. Bowyer, Dr. MacGregor, and two others until

the day after everyone else had gone. I slept in a bed for the first night for about a fortnight and

had the first decent meal for about a week.

The following day I helped load cases of food on to lorries all morning, and then in the

afternoon we motored out to the Mental Hospital. The town was very deserted, parts seemed

quite unscathed but in others the roads and houses were badly knocked about and the overhead

wires of the trackless trams were hanging in festoons all over the place, it was a pathetic sight.

We visited the gaol and one of the other hospitals on the way out, but did not go through the

town proper. Most Europeans had had to go to internment two days before, but there were still

a few trailing out along the road to the internment damp, and a miserable unhappy lot they

looked: men, women, and children tramping out along the road carrying their belongings or

pushing them on some sort of improvised trolley — all in the boiling sun — you can imagine that

4

I did not feel very happy going comfortably in a car. We of course had a good deal further to

go than they but many of them arrived dead beat I know — Sands among them.

The Mental Hospital is not a very inspiring place, big bare wards leading off a long

fenced-in passage with open grass areas in between. The wards were almost completely devoid

of furnishings of any kind, some had bed boards, complete with bed bugs, but most had

nothing at all and the patients had to lie on stretchers or on the bare ground. The hundred or so

of us who had gone out there were no better off; some were in the Superintendent's house and

a few may have had beds to lie in, but most had nothing better than the boards to lie on. I had a

camp bed mattress and a camp bed, but the latter had been looted before I arrived. Fortunately I

still had my tent and I put that up and slept very comfortably on the grass. Everything was

'matey' and totally lacking in organisation, the European ward had both men and women in it,

and so also had the ward in which many of the helpers slept. We were without water for two or

three days, having to carry it from water carts for drinking purposes and go and bathe in a

stream of doubtful cleanliness.

There was plenty of work for those who wanted to work and also plenty of time in

which to laze for those who did not. I found plenty to do carrying stores and stacking them,

making innumerable drinking vessels out of empty tins — there was nothing else for the patients

to drink out of as we had not been allowed to bring anything with us from the General. Feeding

was one of the the greatest snags; the Japanese were in the administration block in which are all

the kitchens, so we had to cook as best we could out in the open under a small marquee. The

food was rice and tinned food mostly, though just before we left we made arrangements for the

supply of fresh vegetables. Things gradually got straightened out and jobs allocated to the

various people who were there, though as it turned out the scheme never went into operation.

WE ARE INTERNED

After we had been there about a week we were suddenly asked whether we were

willing to work under an Asiatic Chief Medical Officer: after some discussion we all said that

we would do so. This was evidently not the answer that had been expected from us because the

very next day we were told to pack our bags and prepare to go into internment. No information

was available as to whether we should get transport or not and it seemed probable that we

would not: so we sorted the wheat from the chaff discarding what we could not carry. I had

already discarded most of my belongings but had sadly to jettison my typewriter, camera, and a

few other personal belongings. A tin trunk with a few things of my own, but chiefly. Book

from the lab and a box containing all I need for survey work I handed over to John Reid. For

some reason the whole of Strahan's crowd had come with us instead going to military

internment, later they were interned and by a stroke of luck I got my survey box back again.

When we had all paraded ready to start we were told we might take the cars that were

available at the Hospital, but by that time we had left the wards unattended for half an hour and

when we returned almost everything had been looted, by the Asiatic staff and patients. The

only discard that I managed to retrieve was my tent, which I still have. We did not know where

we were going to nor when, and in fact we sat in the sun for about three hours before we

eventually got off.

The Journey to the internment camp took us through part of the town and it looked

very little changed from the sorry aspect it presented on our way out to the hospital. We lost the

main party when we were held up at one of the many barriers in the town and went past the

aerodrome, around which were innumerable derelict aeroplanes. Eventually we finished up

along the East Coast Road, beyond the Seaview Hotel; the women stopped off at one house

and we went a little further along the road to a convent school. About 600 others were already

established in a group of five houses next door, living sixteen and twenty to a room. Arthur

Westrop was among them, also Sands, Cheeseman, Byron and many others we know. Arthur

had established himself with two others in a bus and made himself reasonably comfortable, but

on the whole the conditions were dreadfully crowded and uncomfortable. They had been very

short of food for their first few days there. We in the Convent were fairly well off, there were a

5

Sam scott

Sam scottThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.