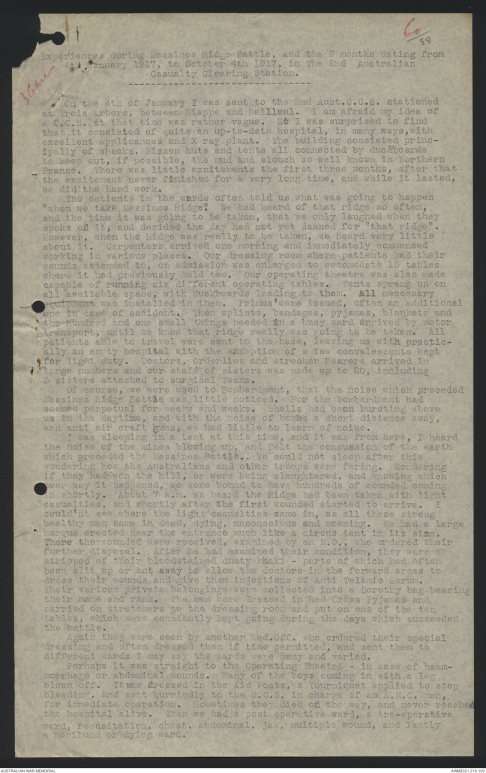

AWM41 1041 - [Nurses Narratives] Sister A N Smith - Part 2

[*60 *]

88

Experiences during Messines Ridge Battle, and the 2 months dating fromxx January 1917, to October 4th 1917, in the 2nd Australian

Casualty Clearing Station

[*3 Copies*]

On the 4th of January I was sent to the 2nd Aust C.C.S. stationed

at Trois Arberes, between Neippe and Bailleul. I am afraid my idea of

a C.C.S. at that time was rather vague. So I was surprised to find

that it consisted of quite an up-to-date hospital, in many ways, with

excellent appliances and X ray plant. The building consisted principally

of shacks, Nissen huts and tents all connected by duckboards

to keep out, if possible, the mud and slouch so well known in Northern

France. There was little excitements the first three months, after that

the excitement never finished for a very long time, and it lasted,

so did the hard work.

The contents of the wards often told us what was going to happen

"when we take Messines Ridge." We had heard of that ridge so often,

and the time it was going to be taken, that we only laughed when they

spoke of it, and decided the day had not yet dawned for "that ridge".

However, when the Ridge was really to be taken, we feared very little

about it. Carpenters arrived one morning and immediately commenced

working in various places. Our dressing room where patients had their

wounds attended to, on admission was enlarged to accomodate 10 tables

where it had previously held two. Our operating theatre was also made

capable of running six different operating tables. Tents sprang up on

all available space, with duckboards leading to them. All necessary

equipment was installed in them. Primus' were issued, often an additional

one in case of accident. Then splints, bandages, pyjamas, blankets and

one hundred and one small things needed in a busy ward arrived by motor

transport, until we knew that ridge really was going to be taken. All

patients able to travel were sent to the base, leaving us with practically

an empty hospital with the exception of a few convalescents kept

for light duty. Doctors, Orderlies and strecher Bearers arrived in

large numbers and our staff of sisters was made up to 20, including

3 sisters attached to surgical Teams.

Of course, we were used to Bombardment, that the noise which preceded

Messines Ridge Battle was little noticed. For the bombardment had

seemed perpetual for weeks and weeks. Shells had been bursting above

us in the daytime, and will the noise of bombs a short distance away,

and anti air craft guns, we had little to learn of noise.

I was sleeping in a tent at this time, and it was from here, I heard

the noise of the mines blowing up, and felt the concussion of the earth

which preceded the Messines Battle. . We could not sleep after this

wondering how the Australians and other troops were faring. Wondering

if they had won the hill, or were being slaughtered, and know which

ever way it happened, we were bound to have hundreds of wounded coming

in shortly. About 7 a.m. we heard the Ridge had been taken with light

casualties, and shortly after the first wounded started to arrive. I

couldn't see where the light casualties came in, as all these strong

healthy men came in dead, dying, unconscious and moaning. We had a large

marque erected near the entrance much like a circus ten in its size.

There the wounded were received, examined by an M.O., who ordered their

further disposal. After he had examined their condition, they were

stripped of their bloodstained duty khaki - parts of which had often

been slit up or cut away to allow the doctors in the forward areas to

dress their wounds and give them injections of Anti Telamlo Serum.

Their various private belongings were collected into a Dorothy bag bearing

their name and rank. The men were dressed in Red Cross pyjamas and

carried on stretchers to the dressing room and put on one of the ten

tables, which were constantly kept going during the days which succeeded

the battle.

Again they were seen by another Med.Off. who ordered their special

dressing and often dress them if time permitted, and sent them to

different wards I may say the wards and were many and varied.

Perhaps it was straight to the Operating Theatre - in case of haemmorrhage

or abdominal wounds. Many of the boys coming in with a leg

blown off. It was dressed in the Aid Posts, a Tourniquet applied to stop

bleeding, and sent hurriedly to the C.C.S. in charge of an A.M.C. man,

for immediate operation. Sometimes they died on the way, and never reached

the hospital alive. Then we had a post operative ward, a pre-operative

ward, resusitation, chest, abdominal, [[ja?]] multiple wound, and lastly

a moribund or dying ward.

-2-

Each patient was sent to a ward, sorted accordingly to his wound and all

necessary treatment and dressing done. We had no time to think of the

hundreds of casualties. We only knew that work was waiting to be done

everywhere, and men were suffering - waiting to be dressed, or to have

an injection of morphia, strychnine or other stimulant, and that many

of them had not had a drink or food for hours.

Everybody worked may hours at a stretch. We had a day and night

staff, but how could anyone go off duty with dying and wounded men all

waiting their turn to be next, and you know that it would be for

hours, before the night or day staff as it happened to be, could cope

with the crowded wards. Everybody tried to have enough sleep to keep

them going, without interfering with the way they did their work, realising

the best work could not be done without some sleep. But how

could anyone sleep, with our big guns firing a short distance from us.

Shells bursting overhead, and air craft and maching guns going continually

with the noise or the general bombardment and the screech of shells

overhead on their way to Bailleul, or Neuys Eglise. Colonel received

great praise, afterwards, for putting through 2,300 cases in 19 hours -

the greater part of which were operated on, and the foreign bodies

removed. Everything must have been well planned. We had all we wanted

and everything went very smoothly. All working very cheerfully together

from the Padre who served the patients with the tea, if we were busy,

to the stretcher bearer who looked, judging by his appearance as if he

were just fit to be carried out on a stretcher himself, instead

of carrying others.

Disposal of patients.

Many patients on admittance were sent to the pre Operative Ward,

there to wait their turn for the X Ray room and theatre. There was

little time for preparation, only that which was necessary being done.

Many of them were too badly wounded to know they were going to the

theatre, Others less wounded were remarkably bright, and only seemed

to want a cigarette, and for you to look after someone who was worse

hit than themselves. Occasionally a doctor came in, and left list of

names as they were to go to the theatre, or a padre came in to see

someone who had not long to live. From the theatre, the very serious

cases were sent to wards for further treatment, and to wait till they

would have recovered from shock and haemorrhage, sufficiently to go

down the line to the Base. The lesser wounded we put in a tent till

the effects of the anasthetic had passed off, they were then put on

the train which ran beside the C.C.S. When one hospital train was

full, it pulled out and an empty hospital train pulled in, waiting

to be filled. I worked in various parts of the hospital, sometimes

in the Operating Room, Abdominal Ward or Dressing Room, or perhaps

the Resusitation Ward assisting the doctors with the various methods

of combating shock and haemorrhage, and trying to help the patients

over this critical time, by giving injections, and special feeding,

to prepare them for the operating theatre, their only hope.

Often we were successful, sometimes our best efforts failed, sometimes

it was hopeless from the beginning.

For some time I had charge of the Moribund or Dying Ward. It was

a hopeless heartbreaking place, roves of dying men, mostly Australians

and New Zealanders, nearly all headcases and uncon/scious and unconscious

or else raving in delirium, and pulling their bandages off. None likely

to live more than a few hours, and pronounced hopeless by the doctors.

Each on a mattress on a stretcher, mostly in their khaki. They were

the only cases not undressed in the admitting tent. Every hour or

so, someone dying and being taken out, only to be followed by someone

else in an hour or so. All we do was try and get them to take

nourishment, give injections to deaden pain; undress them and make them

comfortable. Many of them wore [[?discs]] with their rank and unit on one

side and the next-of-kin's address on the other, seemingly asking

for some one to write to their people and tell them how and when they

died.

German Prisoners (Wounded).

In a tent next to these were German prisoners, mostly wounded and

needing quick operative attention if they were to live. Our own men

were attended to first, unless the germans were very seriously wounded.

-3-

Some of them had been lying out some time, and gas gangrene had been

developed very quickly, where otherwise the wound was not very serious.

They were operated on as quickly as possible and sent xx down the line

to make room for others. Very few could speak a word of English, but

as I had an orderly who could speak German it did not matter much.

Our own men were wonderfully brave about their wounds, seldom complaining,

now and then a groan bursting from them which told how they were

suffering. The germans seldom complained, either, they were good patients.

Only once, and officer complained to me in broken English, but it was

not of his wound. It was to speak of the degradation of the officers

being "put" as he expressed it to "lie with the common soldiers". The

officers were afterwards screened of and their stretchers put on trestles.

Shelling and Bombing of the Cas.Clearing Station.

During all this time of severe work and for weeks after Messines

the C.C.S. had been receiving shells, parts of shells or shrapnel.

Sometimes directed at a balloon between us and the bombs. Sometimes

the germans were shelling the Railway Line and trucks hoping to find

a 12in gun which was kept on a line very close to us, camouflaged as

a truck, and was generally sent up the line at night, at other times

it seemed to us just the shelling of back areas. The staff and patients

had sometimes an anxious time,. Numerous narrow escapes ocurred, but

no one was seriously wounded. For three days and nights after Messines

the night staff worked hours, later than their usual hours and were

kept awake by the noise, until they got so tired they would have slept

thro anything. Bombs were continually being dropped on different

camps, and on the Bailleul-Nieppe road. No one bothered much about

them. We all had the idea that we were safe, because we were a

hospital.

However in July 1917 a taube dropped several bombs just outside

a tent, killing two patients, two orderlies, and wounding 14 or 15

other men. This happened about 10 o'clock at night.

On the afternoon of this same day, the Germans had been shelling

the balloon pretty frequently and pieces were falling in different parts

of the camp. One large piece came down and buried it self in a tent

between two patients, who were side by side on stretchers. It missed

both and one of the patients was an elderly man, and was very much

terrified, and practically suffered from shellshock all the afternoon.

This luck was further out however, as he was one of the patients

killed by the bomb that night.

After this the sisters peace was at an end, a dugout was built for

them. It did not matter where we were working, if a taube appeared

we had to leave our task and go to a dugout, and perhaps remain hours

there. At the time I speak of, the taubes were kept out of the sky

by our machine guns and anti air-craft guns during the day, but always

came over us at night, generally on their way to bomb Hazebrouck and

Bailleul. So we spent most of the day wondering, and spent most of the

night in the dugout - not sleeping. It was underground, and pretty

damp and miserable - until a new one was built above ground for us.

We arose at 5 a.m. to dress the patients to leave by the hospital train

at 6 a.m.

To give some idea of the uncertainty of life surrounding the C.C.S.

One evening a man was admitted, badly wounded by a shell which

exploded in a motor transport waggon on the Bailleul Armentiera Road.

Two friends in his unit hearing he was wounded, rode 14 miles to see

him, on horseback, arriving at 10 p.m. at night just as lights were to be

put out. I spoke to the two men, and told them they need not hurry

away, as their friend was to go down on the hospital train, and they

would not see him again. I left the two men with him and went to supper.

I was not away ½ an hour, when I returned to another ward. As I entered

the stretcher Bearers were taking another man our of a red cross

waggon, I went up to have a look at the patient, as I did so, he

exclaimed "Why, we must be in the same hospital, this is the sister

we were talking to". They were the two men I left talking to their

friend. They had got their horses, rode a few hundred yards from the

camp. A bomb fell between them, killing both horses and wounding pretty

badly the two men - one having his foot blown off. There were so

dazed they did not recognise that it was the same hospital,

-4-

they had just left, till they saw me. All three went down on the

train the next morning.

(Sgd)A.N.Smith, N.S.

No. 1 Aust.Gen.Hospital,

Sutton Veny.

Item Control

Australian War Memorial

005172285

Sam scott

Sam scottThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.