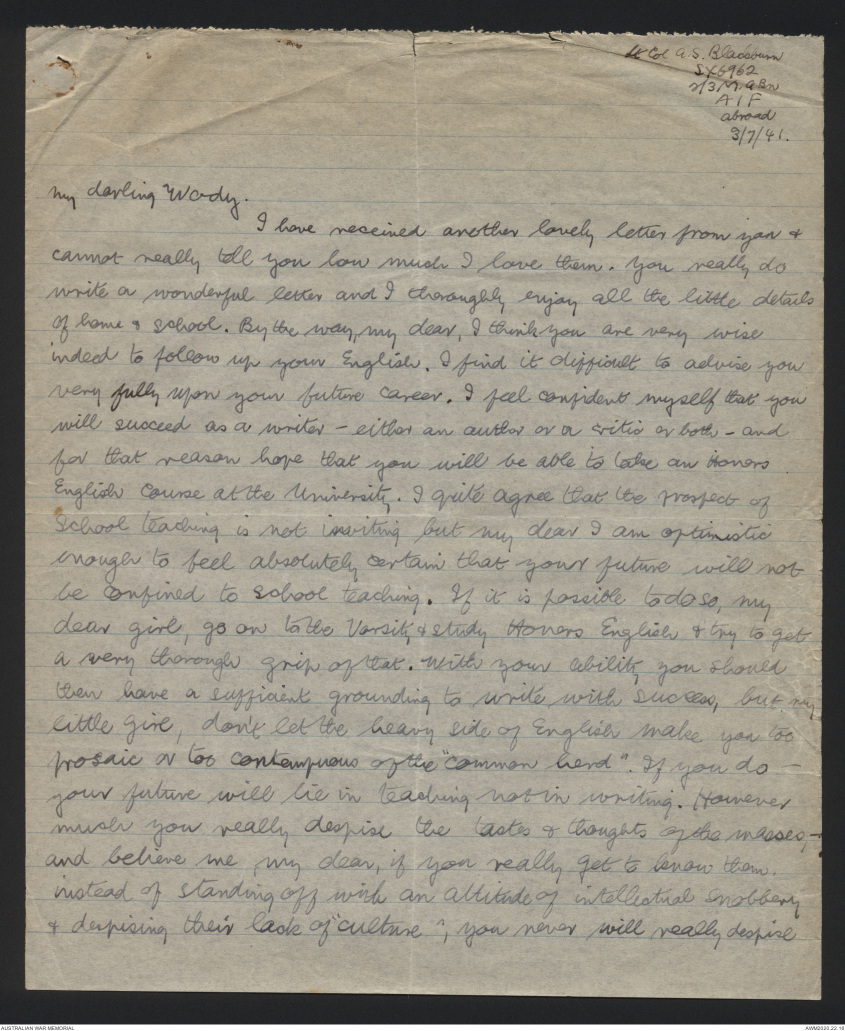

Letters from Arthur Seaforth Blackburn to his family, 1941 - Part 11

Lt Col A.S. Blackburn

SX6962

2/3 M.G Bn

AIF

abroad

3/7/41.

My darling Wody.

I have received another lovely letter from you &

cannot really tell you how much I love them. You really do

write a wonderful letter and I thoroughly enjoy all the little details

of home & school. By the way, my dear, I think you are very wise

indeed to follow up your English. I find it difficult to advise you

very fully upon your future career. I feel confident myself that you

will succeed as a writer - either an author or a critic or both - and

for that reason hope that you will be able to take an Honors

English course at the University. I quite agree that the prospect of

School teaching is not inviting but my dear I am optimistic

enough to feel absolutely certain that your future will not

be confined to school teaching. If it is possible to do so, my

dear girl, go on to the Varsity & study Honors English & try to get

a very thorough grip of that. With your ability you should

then have a sufficient grounding to write with success, but my

little girl, don't let the heavy side of English make you too

prosaic or too contemptuous of the "common herd". If you do -

your future will lie in teaching not in writing. However

much you really despise the tastes & thoughts of the masses, -

and believe me my dear, if you really get to know them,

instead of standing off with an attitude of intellectual snobbery

& despising their lack of "culture", you never will really despise

2/

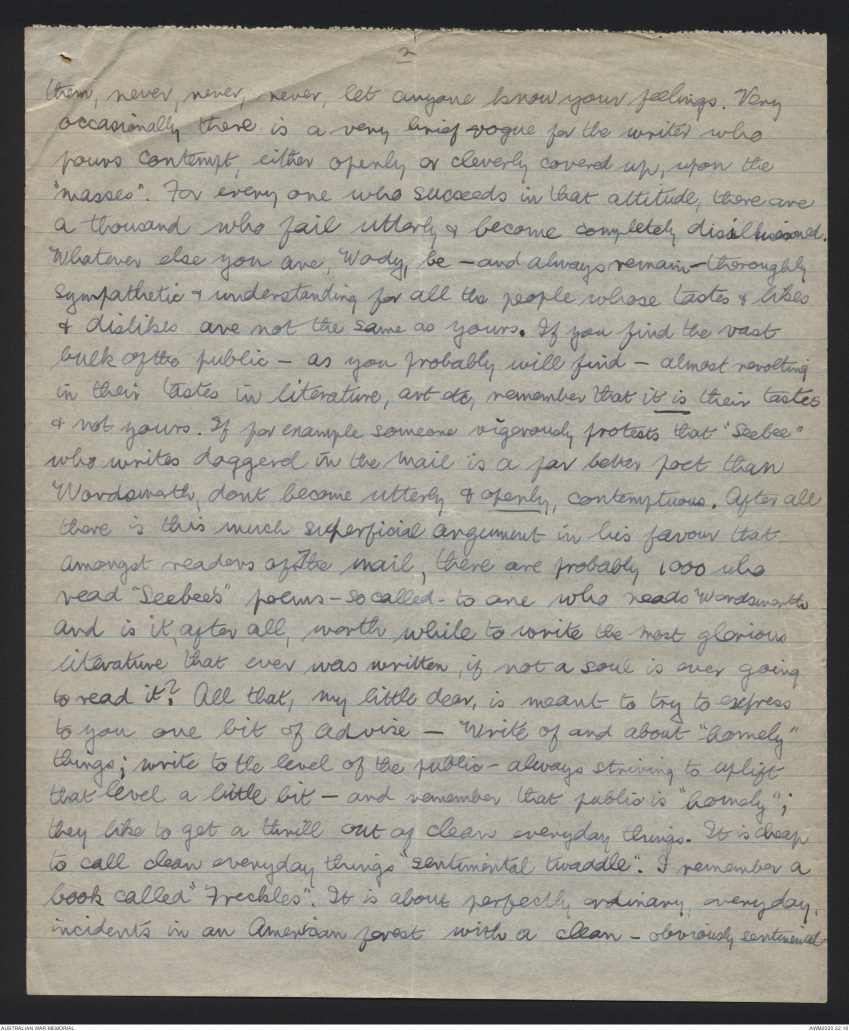

them, never, never, never, let anyone know your feelings. Very

occasionally there is a very brief vogue for the writer who

pours contempt, either openly or cleverly covered up, upon the

"masses". For every one who succeeds in that attitude, there are

a thousand who fail utterly & become completely disillusioned.

Whatever else you are, Wody, be - and always remain - thoroughly

sympathetic & understanding for all the people whose tastes & likes

& dislikes are not the same as yours. If you find the vast

bulk of the public - as you probably will find - almost revolting

in their tastes in literature, art etc, remember that it is their tastes

& not yours. If for example someone vigorously protests that "Seebee"

who writes doggerel in the Mail is a far better poet than

Wordsworth, don't became utterly & openly, contemptuous. After all

there is this much superficial argument in his favour that

amongst readers of the Mail, there are probably 1000 who

read "Seebee's" poems - so called - to one who reads Wordsworths

and is it, after all, worth while to write the most glorious

literature that ever was written, if not a soul is ever going

to read it? All that, my little dear, is meant to try to express

to you one bit of advise - write of and about "homely"

things; write to the level of the public - always striving to uplift

that level a little bit - and remember that public is "homely";

they like to get a thrill out of clean everyday things. It is cheap

to call clean everyday things "sentimental twaddle". I remember a

book called "Freckles". It is about perfectly ordinary, everyday,

incidents in an American forest with a clean - obviously sentimental

3/

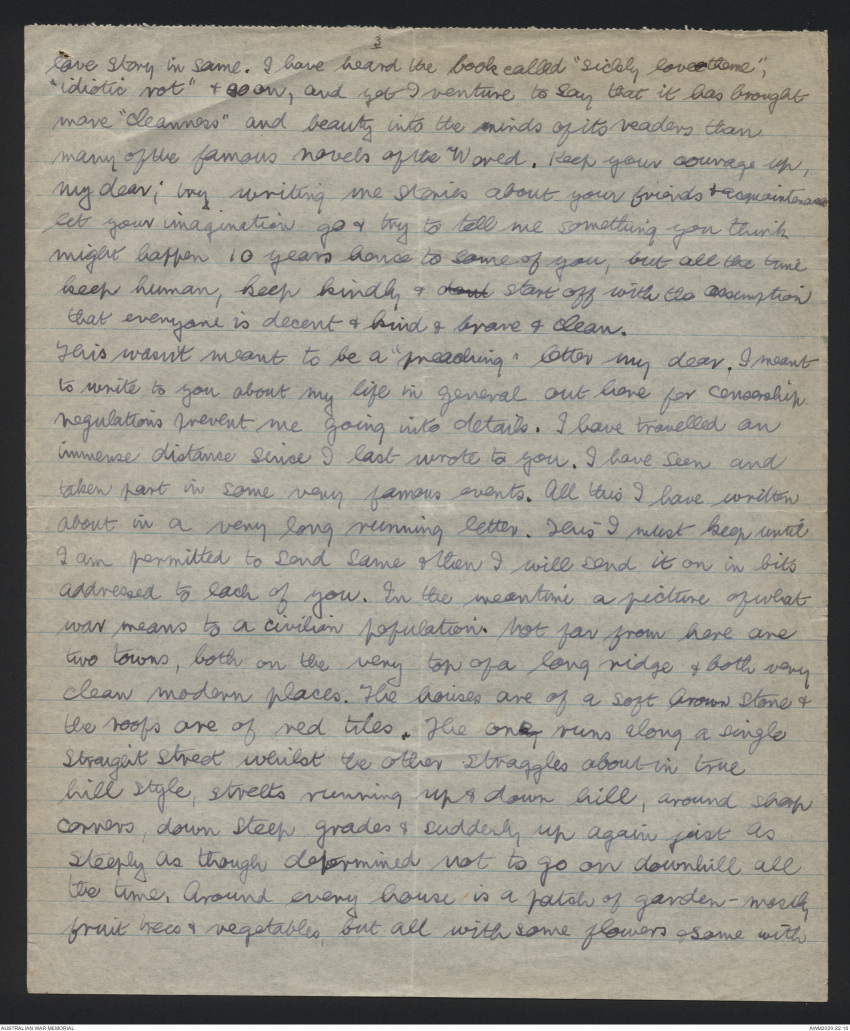

love story in same. I have heard the book called "sickly love-theme",

"idiotic rot" & so on, and yet I venture to say that it has brought

more "cleanness" and beauty into the minds of its readers than

many of the famous novels of the World. Keep your courage up,

my dear; try writing me stories about your friends & acquaintances

let your imagination go & try to tell me something you think

might happen 10 years hence to some of you, but all the time

keep human, keep kindly & dont start off with the assumption

that everyone is decent & kind & brave & clean.

This wasn't meant to be a "preaching" letter my dear. I meant

to write to you about my life in general out here for censorship

regulations prevent me going into details. I have travelled an

immense distance since I last wrote to you. I have seen and

taken part in some very famous events. All this I have written

about in a very long running letter. This I must keep until

I am permitted to send same & then I will send it on in bits

addressed to each of you. In the meantime a picture of what

war means to a civilian population. Not far from here are

two towns, both on the very top of a long ridge & both very

clean modern places. The houses are of a soft brown stone &

the roofs are of red tiles. The one runs along a single

straight street whilst the other straggles about in true

hill style, streets running up & down hill, around sharp

corners, down steep grades & suddenly up again just as

steeply as though determined not to go on downhill all

the time. Around every house is a patch of garden - mostly

fruit trees & vegetables, but all with some flowers & some with

4

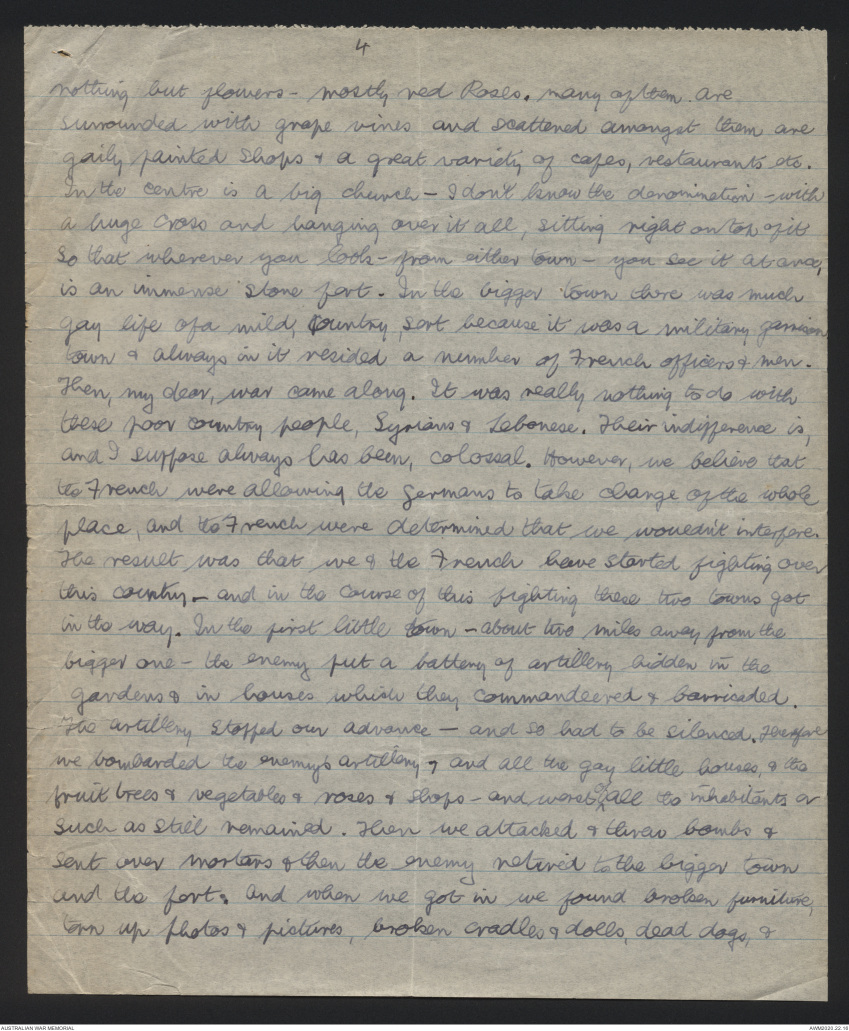

nothing but flowers - mostly red Roses, many of them are

surrounded with grape vines and scattered amongst them are

gaily painted shops & a great variety of cafes, restaurants etc.

In the centre is a big church - I don't know the denomination - with

a huge cross and hanging over it all, sitting right on top of it

So that wherever you look - from either town - you see it at once,

is an immense stone fort. In the bigger town there was much

gay life of a mild, country, sort because it was a military garrison

town & always in it resided a number of French officers & men.

Then, my dear, war came along. It was really nothing to do with

these poor country people, Syrians & Lebanese. Their indifference is,

and I suppose always has been, colossal. However, we believe that

the French were allowing the Germans to take charge of the whole

place, and the French were determined that we wouldn't interfere.

The result was that we & the French have started fighting over

this country - and in the course of this fighting these two towns got

in the way. In the first little town - about two miles away from the

bigger one - the enemy put a battery of artillery hidden in the

gardens & in houses which they commandeered & barricaded.

The artillery stopped our advance - and so had to be silenced. Therefore

we bombarded the enemy's artillery & and all the gay little houses, & the

fruit trees & vegetables & roses & shops - and worst of all its inhabitants or

such as still remained. Then we attacked & threw bombs &

sent over mortars & then the enemy retired to the bigger town

and the fort: and when we got in we found broken furniture,

torn up photos & pictures, broken cradles & dolls, dead dogs, &

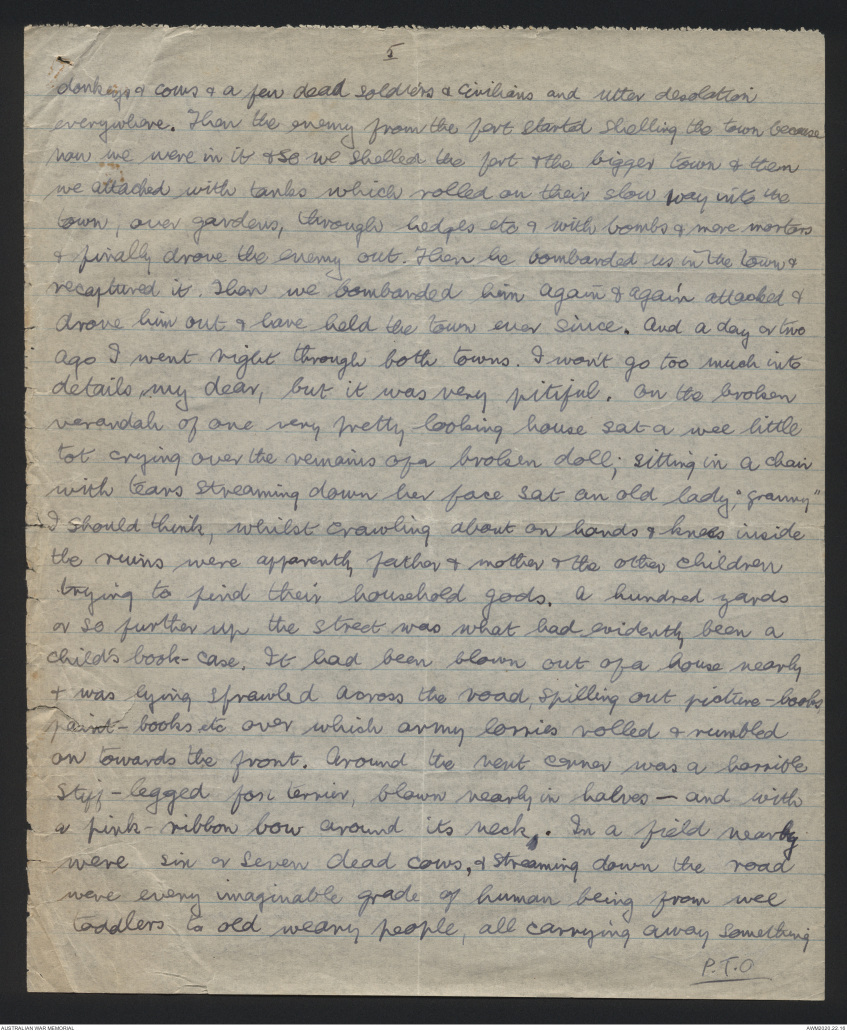

5/

donkeys & cows & a few dead soldiers & civilians and utter desolation

everywhere. Then the enemy from the fort started shelling the town because

now we were in it & so we shelled the fort & the bigger town & then

we attacked with tanks which rolled on their slow way into the

town, over gardens, through hedges etc & with bombs & more mortars

& finally drove the enemy out. Then he bombarded us in the town &

recaptured it. Then we bombarded him again & again attacked &

drove him out & have held the town ever since. And a day or two

ago I went right through both towns. I won't go too much into

details my dear, but it was very pitiful. On the broken

verandah of one very pretty looking house sat a wee little

tot crying over the remains of a broken doll; sitting in a chair

with tears streaming down her face sat an old lady, "granny"

I should think, whilst crawling about on hands & knees inside

the ruins were apparently father & mother & the other children

trying to find their household goods. A hundred yards

or so further up the street was what had evidently been a

child's book-case. It had been blown out of a house nearby

& was lying sprawled across the road, spilling out picture-books

paint-books etc over which army lorries rolled & rumbled

on towards the front. Around the next corner was a horrible

stiff-legged fox terrier, blown nearly in halves - and with

a pink-ribbon bow around its neck,. In a field nearby

were six or seven dead cows, & streaming down the road

were every imaginable grade of human being from wee

toddlers to old weary people, all carrying away something

P.T.O

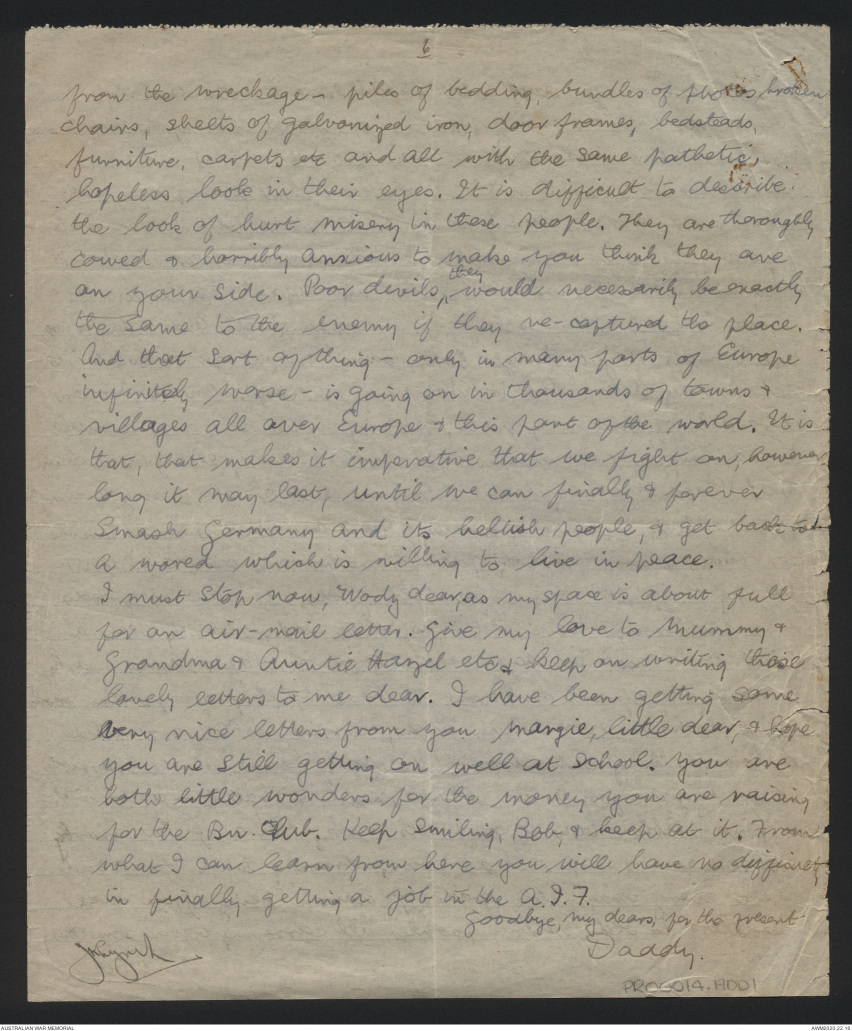

6/

from the wreckage - piles of bedding, bundles of photos, broken

chairs, sheets of galvanized iron, door frames, bedsteads,

furniture, carpets etc and all with the same pathetic

hopeless look in their eyes. It is difficult to describe

the look of hurt misery in these people. They are thoroughly

cowed & horribly anxious to make you think they are

on your side. Poor devils they would necessarily be exactly

the same to the enemy if they re-captured the place.

And that sort of thing - only in many parts of Europe

infinitely worse - is going on in thousands of towns &

villages all over Europe & this part of the world. It is

that, that makes it imperative that we fight on, however

long it may last, until we can finally & forever

Smash Germany and its hellish people, & get back to

a world which is willing to live in peace.

I must stop now, Wody dear, as my space is about full

for an air-mail letter. Give my love to Mummy &

Grandma & Auntie Hazel etc & keep on writing those

lovely letters to me dear. I have been getting some

very nice letters from you Margie, little dear, & hope

you are still getting on well at school. You are

both little wonders for the money you are raising

for the Bn. Club. Keep Smiling, Bob & keep at it. From

what I can learn from here you will have no difficulty

in finally getting a job in the A.I.F.

Goodbye, my dears, for the present

Daddy.

JKLynch

Jacqueline Kennedy

Jacqueline KennedyThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.