Memoir of Eric Francis Maher, 1945 - Part 3

19.

sidue of Red Cross packing cases and odd scraps of other timber

out of a wooden barrack which had been set aside by the Germans

to serve this purpose, presumably in order to keep our minds off

escaping.

For several months, I edited a daily paper called "The

Daily Graph" which was eventually refused publication by the Germans

on account of uncomplimentary references which the paper made

to them. It was designed to record the state of the morale prevalent

in the camp and as the morale naturally rose with allied victories

just before and after the invasion, it followed, as a matter of

course, that much of the printed matter would be objectionable

to the Germans.

I read such books as it was possible to obtain - some of

them were excellent indeed; I wrote criticisms of plays and on

camp policy and government, on such scraps of paper as I could

obtain; I played much sport and took part in other activities

which cannot at present be recorded herein.

It would seem then that I managed to fill in the time well

and fully. Nothing, however, could be more contrary to the truth

The standard 24 hours of every day seemed like a much lengthier

period. Time dragged miserably by and I sank into a mental,

moral and physical laziness - along with many another fellow - and

felt the abject depression known only by those who are denied the

free and unstinted privilege of enjoying the normal and necessary

amenities of life.

Though at times, and for quite long periods, this strange

nightmare existence took on the hues of reality and normality -

incredible and fantastic as it may appear - the knowledge of what

one was missing and of how one's youth was dwindling away was ever

present is the background, tempting, tantalising, maddening!

The few available text books on such subjects as the German

language, economics, French and bookkeeping and accountancy

provided material for the exercise of the mind and without them I

should have noticed more strongly the passing of the weary hours.

Everything in the way of reading material, sports equipment,

writing materials, study books, books of plays, sheet music,

band instruments, stage make-up, cooking utensils and the main

thing of all, food, were of course supplied through the International

Red Cross Society and the Y.M.C.A.

P.O.W's can never be thankful enough that such an organisation

as the Red Cross Society exists. Without the food supplied

by them we should of starved in a physical sense; without the

books, games etc. we should have starved mentally. No greater

tribute can be paid to the work done by the Red Cross! No

greater illustration of the need for such an organisation can be

provided. I shall personally always be proud to shout their

praises from the highest rooftops and will ever count myself

indebted to the Red Cross for my life.

To illustrate how necessary it was to supply prisoners with

Red Cross food parcels, I set out below a rough copy of the German

scale of food rations. This is according to my memory but is, I

think, accurate.

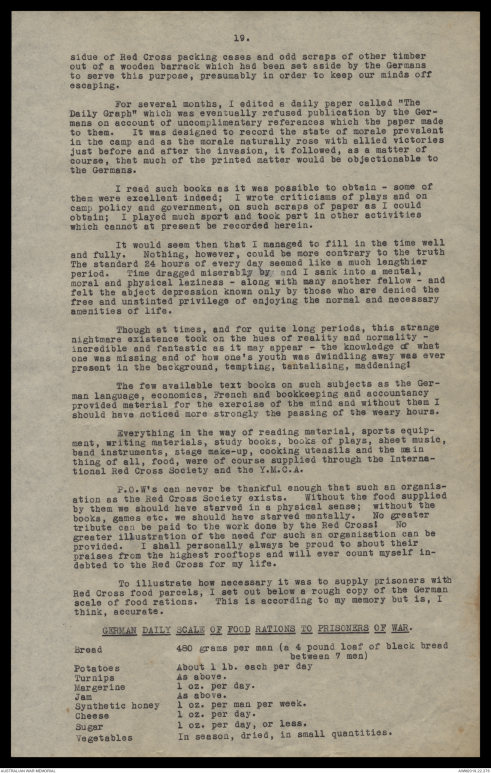

GERMAN DAILY SCALE OF FOOD RATION TO PRISONERS OF WAR.

Bread 480 grams per man (a 4 pound loaf of black bread

between 7 men)

Potatoes About 1 lb. each per day

Turnips As above.

Margarine 1 oz. per day.

Jam As above.

Synthetic honey 1 oz. per man per week.

Cheese 1 oz. per day.

Sugar 1 oz. per day, or less.

Vegetables In season, dried, in small quantities.

20.

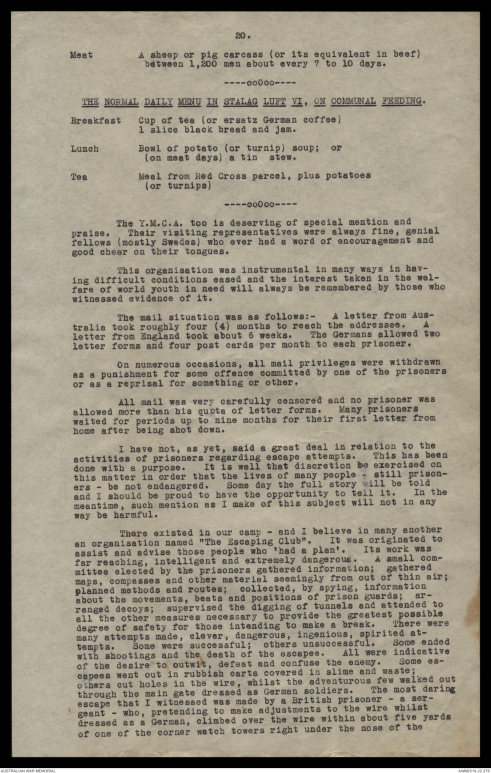

Meat A sheep or pig carcass (or the equivalent in beef)

between 1,200 men about 7 to 10 days.

THE NORMAL DAILY MENU IN STALAG LUFT VI. ON COMMUNAL FEEDING.

Breakfast Cup of tea ( or ersatz German coffee)

1 slice black bread and jam.

Lunch Bowl of potato (or turnip) soup; or

(on meat days) a tin stew.

Tea Meal from Red Cross parcel, plus potatoes

(or turnips)

The Y.M.C.A. too is deserving of special mention and

praise. Their visiting representatives were always fine, genial

fellows (mostly Swedes) who ever had a word of encouragement and

good cheer on their tongues.

This organisation was instrumental in many ways in having

difficult conditions eased and the interest taken in the welfare

of world youth in need will always be remembered by those who

witnessed evidence of it.

The mail situation was as follows:- A letter from Australia

took roughly four (4) months to reach the addressee. A

letter from England took about 6 weeks. The Germans allowed two

letter forms and four post cards per month to each prisoner.

On numerous occasions, all mail privileges were withdrawn

as a punishment for some offence committed by one of the prisoners

or as a reprisal for something or other.

All mail was very carefully censored and no prisoner was

allowed more than his quota of letter forms. Many prisoners

waited for periods up to nine months for their first letter from

home after being shot down.

I have not, as yet, said a great deal in relation to the

activities of prisoners regarding escape attempts. This has been

done with purpose. It is well that discretion be exercised on

this matter in order that the lives of many people - still prisoners -

be not endangered. Some day the full story will be told

and I should be proud to have the opportunity to tell it. In the

meantime, such mention as I make of this subject will not in any

way be harmful.

There existed in our camp - and I believe in many another

an organisation named "The Escaping Club". It was organised to

assist and advise those people who 'had a plan'. Its work was

far reaching, intelligent and extremely dangerous. A small committee

elected by the prisoners gathered information; gathered

maps, compasses and other material seemingly from out of thin air;

planned methods and routes; collected, by spying, information

about the movements, beats and positions of prison guards; arranged

decoys; supervised the digging tunnels and attended to

all the other measures necessary to provide the greatest possible

degree of safety for those intending to make a break. There were

many attempts made, clever, dangerous, ingenious, spirited attempts.

Some were successful; others unsuccessful. Some ended

with shootings and the death of the escapee. All were indicative

of the desire to outwit, defeat and confuse the enemy. Some escapees

went out in rubbish carts covered in slime and waste;

others cut holes in the wire, whilst the adventurous few walked out

through the main gate dressed as German soldiers. The most daring

escape that I witnessed was made by a British prisoner - a sergeant -

who, pretending to make adjustments to the wire whilst

dressed as a German, climbed over the wire within about five yards

of one of the corner watch towers right under the nose of the

21.

guard. He was gone for several months before the Germans

discovered his absence.

Most of these escape attempts equalled many of the deeds

of bravery which have been carried out by men of daring during

the progress of the war, and were deserving the high decorations

for the display of courage and skill in the face of the enemy.

those who were successful however won greater honour - they won

their freedom.

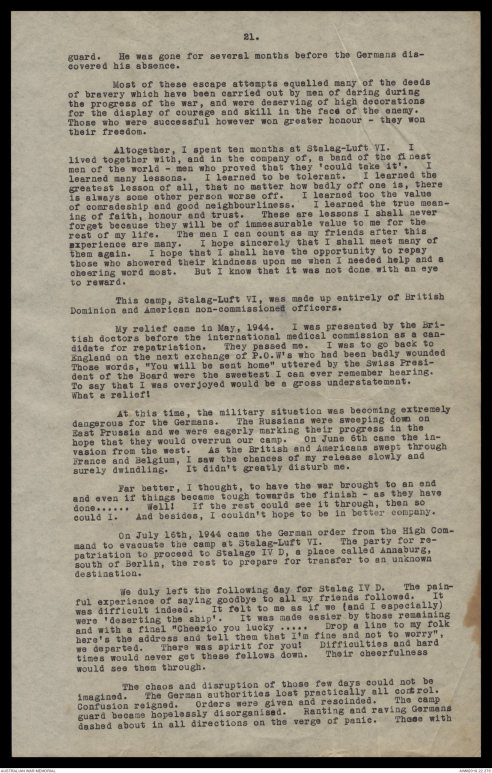

Altogether, I spent ten months at Stalag-Luft VI. I

lived together with, and in the company of, a band of the fi nest

men of the world - men who proved that they 'could take it'. I

learned many lessons. I learned to be tolerant. I learned the

greatest lesson of all, that no matter how badly off one is, there

is always some other person worse off. I learned too the value

of comradeship and good neighbourliness. I learned the true meaning

of faith, honour and trust. These are lessons I shall never

forget because they will be of immeasurable value to me for the

rest of my life. The men I can count as my friends after this

experience are many. I hope sincerely that I shall meet many of

them again. I hope that I shall have the opportunity to repay

those who showered their kindness upon me when I needed help and a

cheering word most. But I know that it was not done with an eye

to reward.

This camp, Stalag-Luft VI, was made up entirely of British

Dominion and American non-commissioned officers.

My relief came in May, 1944. I was presented by the British

doctors before the international medical commission as a

candidate for repatriation. They passed me. I was to go back to

England on the next exchange of P.O.W's who had been badly wounded.

Those words, "You will be sent home" uttered by the Swiss President

of the Board were the sweetest I can ever remember hearing.

To say that I was overjoyed would be a gross understatement.

What a relief!

At this time, the military situation was becoming extremely

dangerous for the Germans. The Russians were sweeping down on

East Prussia and we were eagerly marking their progress in the

hope that they would overrun our camp. On June 6th came the invasion

from the west. As the British and Americans swept through

France and Belgium, I saw the chances of my release slowly and

surely dwindling. It didn't greatly disturb me.

Far better, I thought, to have the war brought to an end

and even if things became tough towards the finish - as they have

done . . . . . Well! If the rest could see it through, then so

could I. And besides, I couldn't hope to be in better company.

On July 16th, 1944 came the German order from High Command

to evacuate the camp at Stalag-Luft VI. The party for repatriation

to proceed to Stalag IV D, a place called Annaburg,

south of Berlin, the rest to prepare for transfer to an unknown

destination.

We duly left the following day for Stalag IV D. The painful

experience of saying goodbye to all my friends followed. It

was difficult indeed. It felt to me as if we (and I especially)

were 'deserting the ship'. It was made easier by those remaining

and with a final "Cheerio you lucky . . . . . . Drop a line to my folk

here's the address and them that I'm fine and not to worry",

we departed. There was spirit for you! Difficulties and hard

times would never get these fellows down. Their cheerfulness

would see them through.

The chaos and disruption of those few days could not be

imagined. The German authorities lost practically all control.

Confusion reigned. Orders were given and rescinded. The camp

guard became hopelessly disorganised. Ranting and raving Germans

dashed about in all directions on the verge of panic. Those with

22.

rifles became 'itchy on the trigger finger' and if it had been

for the cool, sensible attitude of the prisoners themselves a real

slaughter might well have resulted.

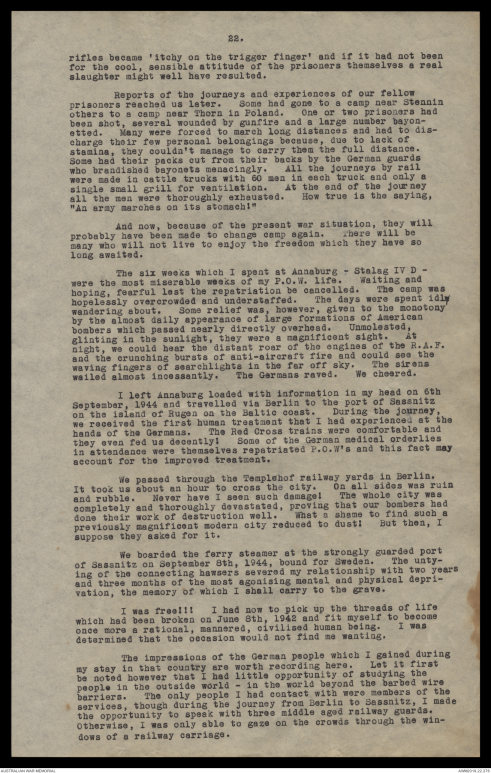

Reports of the journeys and experiences of our fellow

prisoners reached us later. Some had gone to a camp near Stennin

others to a camp near Thorn in Poland. One or two prisoners had

been shot, several wounded by gunfire and a large number bayonetted.

Many were forced to march long distances and had to discharge

their few belongings because, due to the lack of

stamina, they couldn't manage to carry them the full distance.

Some had their packs cut from their backs by the German guards

who brandished bayonets menacingly. All the journeys by rail

were made in cattle trucks with 60 men in each truck and only a

single small grill for ventilation. At the end of the journey

all the men were thoroughly exhausted. How true is the saying

"An army marches on its stomach!"

And now, because of the present war situation, they will

probably be made to change camp again. There will be

many who will not live to enjoy freedom which they have so

long awaited.

The six weeks which I spent at Annaburg - Stalag IV D -

were the most miserable weeks of my P.O.W. life. Waiting and

hoping, fearful lest the repatriation be cancelled. The camp was

hopelessly overcrowded and understaffed. The days were spent idly

wandering about. Some relief was, however, given to the monotony

by the almost daily appearance of large formations of American

bombers which passed nearly directly overhead. Unmolested,

glinting in the sunlight, they were a magnificent sight. At

night, you could hear the distant roar of the engines of the R.A.F.

and the crunching bursts of anti-aircraft fire and could see the

waving fingers of searchlights in the far off sky. The sirens

wailed almost incessantly. The Germans raved. We cheered.

I left Annaburg loaded with information in my head on 6th

September, 1944 and travelled via Berlin to the port of Sassnitz

on the island of Rugen on the Baltic coast. During the journey,

we received the first human treatment that I had experienced at the

hands of the Germans. The Red Cross trains were comfortable and

they even fed us decently! Some of the German medical orderlies

in attendance were themselves repatriated P.O.W's and this fact may

account for the improved treatment.

We passed through Templehof railway yards in Berlin.

It took us about an hour to cross the city. On all sides was ruin

and rubble. Never have I seen such damage! The whole city was

completely and thoroughly devastated, proving that our bombers had

done their work of destruction well. What a shame to find such a

previously magnificent modern city reduced to dust! But then, I

suppose they asked for it.

We boarded the ferry steamer at the strongly guarded port

of Sassnitz on September 8th, 1944, bound for Sweden. The untying

of the connecting hawsers severed my relationship with two years

and three months of the most agonising mental and physical

deprivation, the memory of which I shall carry to the grave.

I was free!!!! I had now to pick up the threads of life

which had been broken on June 8th, 1942 and fit myself to become

once more a rational, mannered, civilised human being. I was

determined that the occasion would not find me wanting.

The impressions of the German people which I gained during

my stay in that country are worth recording here. Let it first

be noted however that I had little opportunity of studying the

people in the outside world - in the world beyond the barbed wire

barriers. The only people I had contact with were members of the

services, though during the journey from Berlin to Sassnitz, I made

the opportunity to speak with three middle aged railway guards.

Otherwise, I was only able to gaze on the crowds through the

windows of a railway carriage.

23.

I found that the German nation was impressionably militaristic.

They were well, possibly over, disciplined, though

one gained the idea that they were rather blindly obedient.

They lived in constant fear of the black-shirted Gestapo and the

next highest and so on, men of military rank. They were regimented

and suppressed and bore themselves automaton fashion.

They were arrogant, excitable - even panicky - and proud. They

held high regard for ceremony and fashionable and showy regalia,

and loved a parade. The seeds of future militarism were sown in

the 'Hitler Jugend' (Youth organisations) who marched, sang and

'Heiled' their way to manhood and womanhood. These organisations

were well trained in such things as bushcraft (they uncovered many

an escapee because of this), knowledge of rifles, aircraft and

ship recognition, etc. etc.

Though the majority of the guards were easily bribed and

noticably corruptible because of the shortage of soap, coffee and

cigarettes, many - particularly the officer class - were kept

honest by either their distinct pride or their fear of the

consequences if they were caught. Several German soldiers found to

be looting Red Cross supplies were given extremely severe sentences

whilst, on one occasion, as mentioned before, one of the

guards hanged himself to escape the wrath of the Gestapo for

"betraying the fatherland".

Many of the higher officers were cruel, bitter and at time

sadistic, and when allied victories and air blows were announced,

these traits became most marked. Individually the guards were

cowards. This was most noticeable and was the cause of many of

the atrocious shootings which took place. This cowardliness in

the individual indicated a most obvious inferiority complex and

all the 'blather' about 'master race' and 'Aryanism' was a veneer

which merely made the complex and pronounced.

The whole race appeared to be very gullible and credulous

as was proved by their belief of Nazi propaganda. A military defeat

was never conceded - it was always announced as a 'tactical

withdrawal' or a 'planned alteration of the line'. The severe

allied air blows cut the people deeply and a great hate of British

and American personnel was built up by the Nazi propagandists with

the use of such words as 'brutal' 'callous' and 'inhuman'. Many

allied airmen are known to have been slaughtered by the civil

population after parachuting to earth in the target area.

Our camp propagandists did good work by reminding the German

soldiers of the shameful, indiscriminate bombing of Warsaw,

Coventry, Prague and Liverpool in the early days of the war, a

fact they seemed to have forgotten.

Their phrase "Es ist kein kreig mehr" (it is no longer war)

meaning it is now mere annihilation, gave the impression that

whilst they disregarded the rules of common decency and humaneness

themselves, they expected enemy nations to abide by them rigidly

and absolutely.

They have shown by their achievements in this war that

they are clever, cunning, industrious, devilish and determined.

The Gestapo is a model organisation for the propagation of fear.

The German Intelligence Service is remarkably well informed.

The cost of battle is never taken into account. Nothing stands

in the way. "The weak must go to the wall" is their motto and

it seems to be a fitting one for their purpose.

My conversation with the railway guards led me to believe

that the first signs of discontent had been born. They had been

fooled by the Nazi ideal and were just awakening from the trance;

but it will be many months before the rising swell of dissatisfaction

assumes proportions sufficiently strong to cause the overthrow

of the powers that reign. Indeed, it appears that the

country will now be overrun and defeated before such a thing as

internal revolt has time to materialise.

24.

We eventually arrived, in the late afternoon of 28th

September, at the Swedish port of Trelleborg. We unshipped and

transferred to a train which was to take us to the port of

Gothenberg and to the boat for England. The Swedish people (now

decidedly pro-British) and the Swedish Red Cross gave us a marvellous

welcome. They fed us, pampered us, sympathised, carried

our bags and did everything to help us in the realisation

that we had again come out into the world of freedom.

How grand it was to see all the lights! The whole country

appeared as some new fantastic fairyland and gave new life

and cheer to us all.

At Gothenberg three ships were awaiting our arrival -

the Gripsholm, the Drottingholm and the Arundel Castle. I was

embarked on the Gripsholm. We sailed in convoy, protected and

escorted through the minefield by a German destroyer. Night

fell and I retired to the first sleep of peace for a long, long

time. When morning came we were anchored in the port of

Christiansand on the southern tip of Norway and were surrounded by

small craft flying the Nazi war flag. My heart was in my mouth!

Surely nothing could have gone wrong at this stage? German

officials came aboard and after a nine hour search, removed three

civilian passengers. Could they have been agents? We were then

allowed to continue on the way.

A week of perfect sea travel followed. Good weather, a

fully lighted ship and such food as I had not tasted since I left

Australia in October, 1940. We were even given fruit - oranges,

apples etc. - as much as we could eat and more. Glorious!

Almost everyone received a full set of clothing. The

Red Cross officials gave out cigarettes, sweets, toilet requisites -

almost all the things of which we were in dire need - until

I thought that it must be a dream and that I should awaken to

find that it was all unreal and that I was, in fact, still back

behind barbed wire.

But on. On, to England!

Liverpool, Saturday, September 16th, 1944. Time: About

2 p.m. Bands playing; crowds cheering; ferry boats blowing

their hooters; flags flying in the breeze, flags of all the

United Nations - see the Australian flag . . . . there it is . . . . .

no! not there . . . . right in the middle. Everyone chattering.

Everyone with tears in their eyes. Some smiling. Some too

bewildered to smile. England . . . . . . home at last!

A skurrying of deck hands. Ropes thrown over to the

wharf . . . . . a few last 'Boops' from the tugs and there we were,

docked safe and sound.

A British General at the microphone. Absolute quiet.

The General speaks: "I have been commanded by His Majesty, the

King, to give you the following message from the King and Queen -

'We all know what you have been through . . . .may you all have a

quick return to good health' . . . . .Three rousing cheers. Then, the

General again. "I have no need to tell you of the work of the

Red Cross . . . . ." He can say that again. We shan't forget.

Down with the gang plank and off we go . . . . .thousands of

people waving and cheering . . . . . everyone happy . . . .cigarettes and

sweets being pushed into our hands . . . . a few words from the

welcoming Australian officers, Red Cross officials and other

representatives and then into the bus which was to take us the R.A.F

hospital at Weeton, near Blackpool.

What a day of days! One never to be forgotten, because

we shall always remember what it meant.

48 hours - or was it less - at Weeton, during which time

we were given a thorough medical examination, a full set of new

clothing, received ration cards, identity cards, a thousand and

25.

one other things - and best of all - 28 day leave pass.

I went to London. Brother Dick (from whom I had received

a welcoming note) was at the station to meet me. We

hadn't seen each other for four years. He took me out to his

billet at Turnpipe Lane where I stayed for abut a week. We

talked, and talked, and talked.

The next three weeks were spent travelling all over

the country - North to see some old friends and to talk of old

times on the squadrons - to York to visit an old Irish friend

who had also been a P.O.W. - to West Drayton to spend some

time with Mrs. Florey at the 'Anchor', and so on.

My vocabulary is not sufficiently mature nor extensive

to fully describe my reactions to this new birth of freedom.

Much of the whirl of excited and scurrying travel was gone

through in the state of semi-realisation and I fear that my

brain, lethargic because of the long period of mental stagnation

experienced, failed to register and record many of the events of

these weeks, I met and talked with many people. I read -

devoured hungrily would be a better description - every available

newspaper. I bought books and magazines. I re-read my

diary. I studied back numbers of Hansard to enjoy parliamentary

debates long since forgotten. I sought information on

a thousand subjects to fill in the gap caused by two years'

absence.

I ate and drank and slept in peace, comfort and security.

All food seemed delicious. I couldn't understand people who

groused because this or that wasn't quite right; wasn't well

cooked; was not delicately prepared. To me, it was most

appetising and was consumed with relish. A pleasant drink of

beer or a glass of fine wine - a treat long denied me - was

sipped, inspected and made to last. A comfortable bed with

clean sheets spelled Heaven. All three in studied moderation

until I once more became a connoisseur of these three of life's

most prized pleasures.

I found myself shy and embarrassed in company and unable

to express my true feelings and appreciation. My once free

flow of small talk and conversation was missing. I became

physically tired out very quickly and for a long time felt awkward,

clumsy and 'out of things' generally. My manners at the

table and in company were anything but satisfactory. I usually

managed to say the wrong thing at the wrong time.

All these traits, however, and faults were quickly

straightened out. I gained confidence by taking every opportunity

of meeting people and talking. I was soon able to hold

my own again, confident in the knowledge that I had overcome my

difficulties and shyness.

I spoke at Rotary Club luncheons; addressed members of

squadrons on my experiences as a P.O.W. and called on people that

I knew who held comparatively high office. I constantly read

good books. My mental laziness departed and my conversation

became free and easy.

Soon all was well again.

I returned from leave and determined to regain some

measure of health and to take advantage of specialised medical

treatment before going home, lest my people and friends be

disappointed, r have cause to be sympathetic. I arranged to spend

some time at a rehabilitation centre at Hoylake, near Liverpool.

This was a great spot. A beautiful, suburban ex-boys'

school with swimming pools, golf course, cricket and football

field, squash and tennis courts, billiard room and gymnasium, it

had been presented to the R.A.F. for the duration of the war to

be used for this very purpose.

26.

We were given grand treatment and I soon began to feel

well physically and mentally.

Still wondering how I should appear to the folks at

home - would they think me changed, be disappointed or glad?

etc. etc. - but confident that I could now present myself in a

satisfactory light, I asked to be allowed to proceed to the

embarkation depot at Brighton for transfer to Australia.

I spent a final glorious Christmas at the Anchor Hotel.

It was a Christmas I shall not easily forget. I had been hoping

that my last Xmas in England would be a 'white one'. It was.

Not white with snow, but a hoary, cleansed frost. The whole

scene had a fairyland atmosphere and a picture postcard beauty

which was unforgettably magnificent and reminded me of a passage

from one of Charles Dickens' books - "No fog, just cool, clear

crackling fresh air. Glorious! Glorious!"

Some delay was caused in my departure due to an investigation

which was being made regarding promotion and so I remained

at Brighton for two months. I enjoyed the lazy life and the

atmosphere of England's biggest seaside resort tremendously and, in

addition, met several very old friends who were constantly coming

and going.

My promotion eventually came through and I was commissioned

with effect from the day previous to being reported missing, thus

making me up directly to the rank of Temporary Flight Lieutenant.

A sort period of rush and hurry followed whilst I got

together the necessary kit . . . . . .and then, aboard ship 'bound for

Australia' after an absence of four years and six months.

Sam scott

Sam scottThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.