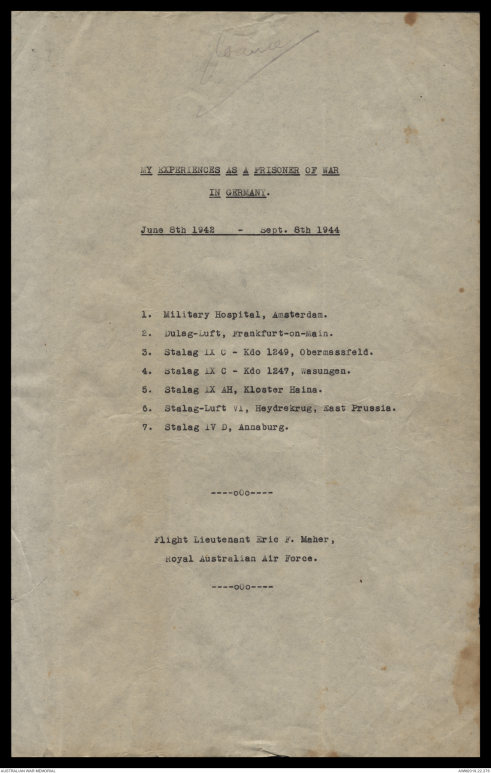

Memoir of Eric Francis Maher, 1945 - Part 1

France

MY EXPERIENCES AS A PRISONER OF WAR

IN GERMANY.

June 8th 1942 - Sept. 8th 1944

- Military Hospital, Amsterdam.

- Dulag-Luft, Frankfurt-on-Main.

- Stalag IX C - Kdo 1249, Obermassfeld.

- Stalag IX C - Kdo 1247, Wasungen.

- Stalag IX AH, Kloster Haina.

- Stalag-Luft VI, Heydrekrug, East Prussia.

- Stalag IV D, Annaburg.

Flight Lieutenant Eric F. Maher,

Royal Australian Air Force.

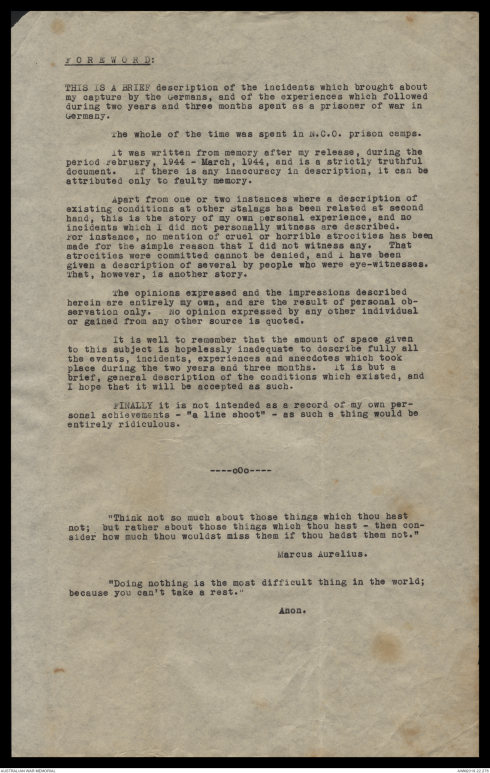

FOREWORD:

THIS IS A BRIEF description of the incidents which brought about

my capture by the Germans, and of the experiences which followed

during two years and three months spent as a prisoner of war in

Germany.

The whole of the time was spent in N.C.O. prison camps.

It was written from memory after my release, during the

period February, 1944 - March, 1944, and is a strictly truthful

document. If there is any inaccuracy in description, it can be

attributed only to faulty memory.

Apart from one or two instances where a description of

existing conditions at other Stalags has been related at second

hand, this is the story of my own personal experience, and no

incidents which I did not personally witness are described.

For instance, no mention of cruel or horrible atrocities has been

made for the simple reason that I did not witness any. That

atrocities were committed cannot be denied, and I have been

given a description of several by people who were eye-witnesses.

That, however, is another story.

The opinions expressed and the impressions described

herein are entirely my own, and are the result of personal

observation only. No opinion expressed by any other individual

or gained from any other source is quoted.

It is well to remember that the amount of space given

to this subject is hopelessly inadequate to describe fully all

the events, incidents, experiences and anecdotes which took

place during the two years and three months. It is but a

brief, general description of the conditions which existed, and

I hope that it will be accepted as such.

FINALLY it is not intended as a record of my own personal

achievements - "a line shoot" - as such a thing would be

entirely ridiculous.

"Think not so much about those things which thou hast

not; but rather about those things which thou hast - then consider

how much thou wouldst miss them if thou hadst them not."

Marcus Aurelius.

"Doing nothing is the most difficult thing in the world;

because you can't take a rest."

Anon.

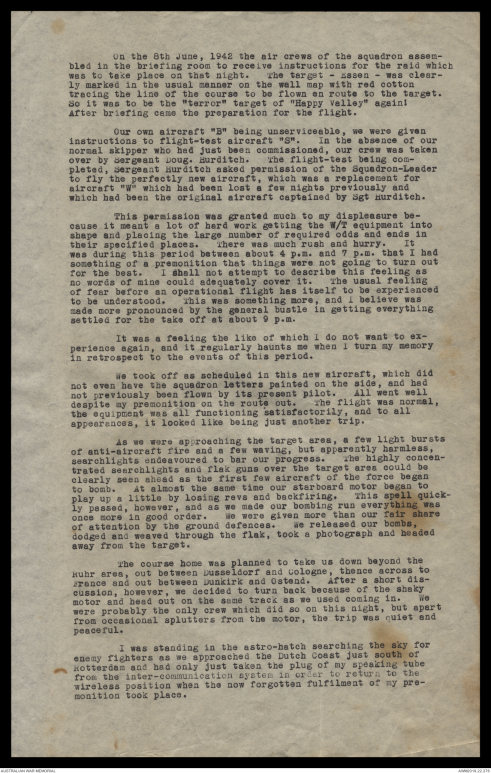

On the 8th June, 1942 the air crews of the squadron assembled

in the briefing room to receive instructions for the raid which

was to take place on that night. The target - Essen - was clearly

marked in the usual manner on the wall map with red cotton

tracing the line of the course to be flown en route to the target.

So it was to be the "terror" target of "Happy Valley" again!

After briefing came the preparation for the flight.

Our own aircraft "B" being unserviceable, we were given

instructions to flight-test aircraft "S". In the absence of our

normal skipper who had just been commissioned, our crew was taken

over by Sergeant Doug. Hurditch. The light-test being completed,

Sergeant Hurditch asked permission of the Squadron-Leader

to fly the perfectly new aircraft, which was a replacement for

aircraft "W" which had been lost a few nights previously and

which had been the original aircraft captained by Sgt Hurditch.

This permission was granted much to my displeasure because

it meant a lot of hard work getting the W/T equipment into

shape and placing the large number of required odds and ends in

their specified places. There was much rush and hurry. It

was during this period between about 4 p.m. and 7 p.m. that I had

something of a premonition that things were not going to turn out

for the best. I shall not attempt to describe this feeling as

no words of mine could adequately cover it. The usual feeling

of fear before an operational flight has itself to be experienced

to be understood. This was something more, and I believe was

made more pronounced by the general bustle in getting everything

settled for the take off at about 9 p.m.

It was a feeling the like of which I do not want to experience

again, and it regularly haunts me when I turn my memory

in retrospect to the events of this period.

We took off as scheduled in this new aircraft, which did

not even have the squadron letters painted on the side, and had

not previously been flown by its present pilot. All went well

despite my premonition on the route out. The flight was normal,

the equipment was all functioning satisfactorily, and to all

appearances, it looked like being just another trip.

As we were approaching the target area, a few light bursts

of anti-aircraft fire and a few waving, but apparently harmless,

searchlights endeavoured to bar our progress. The highly concentrated

searchlights and flak guns over the target area could be

clearly seen ahead as the first few aircraft of the force began

to bomb. At almost the same time our starboard motor began to

play up a little by losing revs and backfiring. This spell quickly

passed, however, and as we made our bombing run everything was

once more in good order. We were given more than our fair share

of attention by the ground defences. We released our bombs,

dodged and weaved through the flak, took a photograph and headed

away from the target.

The course home was planned to take us down beyond the

Ruhr area, out between Dusseldorf and Cologne, thence across to

France and out between Dunkirk and Ostend. After a short discussion,

however, we decided to turn back because of the shaky

motor and head out on the same track as we used coming in. We

were probably the only crew which did so on this night, but apart

from occasional splutters from the motor, the trip was quiet and

peaceful.

I was standing in the astro-hatch searching the sky for

enemy fighters as we approached the Dutch Coast just south of

Rotterdam and had only just taken the plug of my speaking tube

from the inter-communication system in order to return to the

wireless position when the now forgotten fulfilment of my premonition

took place.

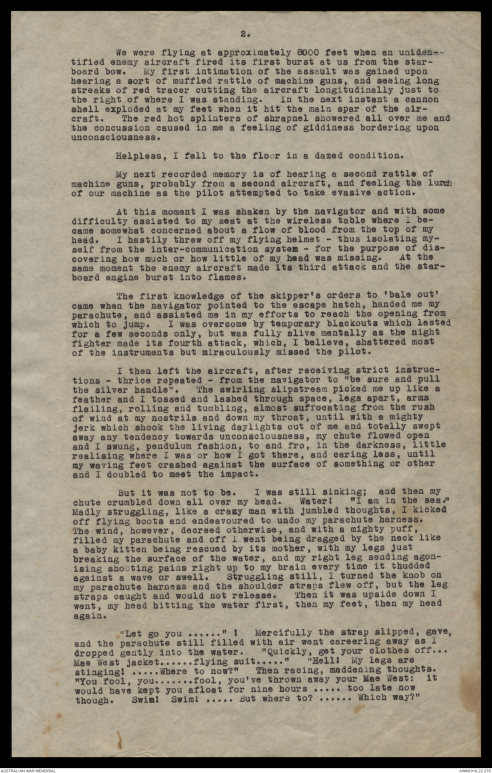

2.

We were flying approximately 8000 feet when an unidentified

enemy aircraft fired its first burst at us from the starboard

bow. My first intimation of the assault was gained upon

hearing a sort of muffled rattle of machine guns, and seeing long

streaks of red tracer cutting the aircraft longitudinally just to

the right of where I was standing. In the next instant a cannon

shell exploded at my feet when it hit the main spar of the aircraft.

The red hot splinters of shrapnel showered all over me and

the concussion caused in me a feeling of giddiness bordering upon

unconsciousness.

Helpless, I fell to the floor in a dazed condition.

My next recorded memory is of hearing a second rattle of

machine guns, probably from a second aircraft, and feeling the lurch

of our machine as the pilot attempted to take evasive action.

At this moment I was shaken by the navigator and with some

difficulty assisted to my seat at the wireless table where I became

somewhat concerned about a flow of blood from the top of my

head. I hastily threw off my flying helmet - thus isolating myself

from the inter-communication system - for the purpose of discovering

how much or how little of my head was missing. At the

same moment the enemy aircraft made its third attack and the starboard engine burst into flames.

The first knowledge of the skippers' orders to 'bale out'

came when the navigator pointed to the escape hatch, handed me my

parachute, and assisted me in my efforts to reach the opening from

which to jump. I was overcome with temporary blackouts which lasted

for a few seconds only, but was fully alive mentally as the night

fighter made its fourth attack, which, I believe, shattered most

of the instruments but miraculously missed the pilot.

I then left the aircraft, after receiving strict instructions

- thrice repeated - from the navigator to "be sure and pull

the silver handle". The swirling slipstream picked me up like a

feather and I tossed and lashed through space, legs apart, arms

flailing, rolling and tumbling, almost suffocating from the rush

of wind at my nostrils and down my throat, until with a mighty

jerk which shook the living daylights out of me and totally swept

away any tendency towards unconsciousness, my chute flowed open

and I swung, pendulum fashion, to and fro, in the darkness, little

realising where I was or how I got there, and caring less, until

my waving feet crashed against the surface of something or other

and I doubled to meet the impact.

But it was not to be. I was still sinking; and then my

chute crumbled down all over my head.. Water! "I am in the sea."

Madly struggling, like a crazy man with jumbled thoughts, I kicked

off flying boots and endeavoured to undo my parachute harness.

The wind, however, decreed otherwise, and with a mighty puff,

filled my parachute and off I went being dragged by the neck like

a baby kitten being rescued by its mother, with my legs just

breaking the surface of the water, and my right leg sending agonising

shooting pains right up to my brain every time it thudded

against a wave or swell. Struggling still, I turned the knob on

my parachute harness and the shoulder straps flew off, but the leg

straps caught and would not release. Then it was upside down I

went, my head hitting the water first, then my feet, then my head

again.

"Let go you......." ! Mercifully the strap slipped, gave,

and the parachute will filled with air went careering away as I

dropped gently into the water. "Quickly, get your clothes off....

Mae West jacket....... flying suit......" "Hell! My legs are

stinging! ........ Where to now?" Then racing, maddening thoughts.

"You fool, you........fool, you've thrown away your Mae West! It

would have kept you afloat for nine hours ...... too late now

though. Swim! Swim! ...... But where to? .... Which way?"

3.

"There! Look, there's something on the horizon. If

it's not land, then you've had it. Get going, it's your only

chance."

And then the painful swim in the rolling sea......mouthfuls

of water........bitter cold........."keep going."

My legs were stinging. Then suddenly I touched the bottom.

"I've touched bottom! My hand touched the bottom! Try with

your feet. Good.......I've made it . I'm safe."

"Wade to shore. Get going......I'm falling. But I

mustn't fall now.......Keep on......Keep on going. It's not deep

here, I'll rest for a minute, and then I'll be alright."

I awoke to find myself lying at the water's edge with the

waves breaking gently over the lower half of my body as if they

were trying to push me ashore; to beach me. But I couldn't get

up. I had no strength. I just had to lie there until my

strength returned. My legs were stinging.......such pain! I

turned my head and then I saw it. There was blood mixing with

the water around my legs. I couldn't attempt to stop the bleeding

because I couldn't move. My every muscle seemed paralysed.

"I must go to sleep. I'm so tired."

"But no! I must stop the bleeding." So clutching the

sand with my fingers and digging in my knees I began to move,

snail-like, out of the water, resting every few yards to regain

my breath. I looked at my watch and it told me that the time

was 18 minutes past 2. I put it to my ear. It had stopped.

"I wonder what the time it can be now?"

The wind blowing against my wet clothes was bitterly cold,

and the pain from my legs was becoming increasingly agonising.

My fingers were beginning to sting also......and my right hip.....

and my head.....and my shoulder......

I crawled forward in the darkness until I was clear of the

water, and eventually reached a sloping bank of loose, fine, sand.

Every time I clutched at the sand it just ran through my fingers.

Maddening! Maddening! And then a dreadful thought struck me,

"Perhaps this beach is mined! Don't move.......Stay where you are."

But the wind was far too cold; I was shivering and had to

get some shelter. So by crawling forward, after what seemed hour

and hours of pain and frustration I scrambled over the bank,

scooped out the sand in the way of digging a trench, climbed in

and pressed the sand over my body still wearing my wet clothes.

Then completely exhausted, I fell asleep.

The gently soothing rays of early morning sunshine awakened

me and I opened my eyes to a perfectly new day. I looked at

my watch again before I realised that it had stopped, but by the

position of the sun I guessed it to be about 9 a.m. When I became

fully awake it seemed as if my whole body was aching. Gnawing

toothache-like pains from my head to my toes. Agonising

little darts of fire burning through my head; and a continual

throbbing, throbbing, throbbing from the waist down. I pushed

back the covering of sand and began to 'lick my wounds'. I felt

my head. It seemed to be all there, though fresh blood came away

on my hand. I pulled back the legs of my battle trousers and was

horrified to see the flesh of both my legs lying open and still bleeding,

though not profusely, and two bone ends appearing through the

gash in my right ankle. "No wonder my legs were aching." I

suddenly felt sick. The sight of the coagulated blood and blood-stained

sand turned my stomach and I began to retch. I covered

my legs with tattered trousers and, because of a sudden twinge

of paid, felt my right hip. It had been torn in a furrow several

inches long, presumably by a stray bullet. My fingers were torn

in several places and both shoulders were bleeding slightly.

"What a mess.....and what a place to be, when in such a mess!"

4.

I gazed about but there appeared to be nothing for miles

around. The land immediately inshore was soggy and shushy, with

a few isolated, barren trees leaning like farmers' scarecrows in

all directions. On the far horizon the sky line was disorganised,

and though my view was interrupted by a rising ridge, I

guessed that there was a village or perhaps a town in that direction.

This later proved to be so.

The pain was now becoming almost unbearable and I decided

to make my way as best I could in the general direction of the

town. The first movement however sent such stabs of pain through

my body that I decided to just lie there and hope for the best;

and if there was no best, to fade away as gently and as peacefully

as possible.

It was about this time that I discovered that there was a

broken bone in my left leg also. I began to examine it and after

doing so, raised my eyes to see a party of armed soldiers, in

green uniforms, about 150 yards away spread out in a half circle making

their way through the long grass with their rifles at the ready.

It was obvious immediately that they were searching for me and for

any other members of the crew who, I presumed, had baled out and

might be in the vicinity.

I saw however that they had not noticed me and appeared to

be passing me by. I decide it was useless to lie there and so I

gave a long shout. They turned quickly and confronted me "en

masse" and I had a ringside view of about fourteen rifle barrels

from the business end!

They approached me cautiously, gesticulating and shouting.

I took their exhortations to mean 'put your hands up' and I did so

without delay. One soldier detached himself from the party and

coming right up, and gave me a real gangster's frisk. As I had no revolver,

hand-grenade or similar weapon in my possession, they all

lowered their rifles to my very great relief; though, at the same

time, if they had put a bullet or two into me I would not have

resented it in any way.

They then began to chatter noisily among themselves. I

was extremely thirsty and weak and decided to ask for water. How

very difficult it is to make people who don't speak one's language

understand what one wants! I said the word 'water' in what I

thought to be every conceivable way. But did they understand?

Did they, Hell! I pointed to the sea. I went through the

motions of turning on the tap, of filling a glass and placing it

to my lips; and finally one of the soldiers who must have been

slightly less dim than the rest, ejaculated, "Ja, Ja! Wasser."

But I didn't get my drink even then.

The party of soldiers then broke up. Four men stayed with

me and the others pressed on with their search. Two of my guards

I took to be officers as the other two were clicking their heels

and saluting them with monotonous regularity. The two officers

took off their greatcoats - beautifully long ones that trailed almost

on the ground, and they placed one on the sand. Then by

taking me by the legs and under the arms placed me upon it. The

other they spread over me. As I was almost blue with cold by

this time, I can't remember anything in my life for which I was

more grateful, and I must say that I began to have quite a regard

for the thoughtfulness of these two men even though they were

Germans.

The two soldiers then disappeared in the direction of the

town and the two officers sat down by me to keep vigil. They

offered me cigarettes and tried to find out the whereabouts of the

other members of my crew by employing an elaborate sign language.

My brain was fairly clear by now and as I thought of the possibility

of the other members of the crew being able to make their

escape, I pointed to the water and made a gesture of hopeless despair

with my hands, shoulders and face. They appeared to understand

that my 'Kameraden' (comrades) had gone into the sea with the

5.

plane, and they returned my gesture. I felt pretty good about

this. I thought it was one up for me!

After about an hour, the two soldiers reappeared with a

horse and dray which they drove through the marshes towards us.

They also brought a flask of water and a flask of vile-tasting

black coffee; both of which I drank straight off. On the dray

was a long wicker rest couch and it was on to this that I was

lifted. One of the soldiers and the two officers mounted the

front of the dray and the other soldier took up position in the

back and we set off over the bumpy, winding trail.

It was to be the most uncomfortable and humiliating journey

of my life.

After travelling for some time, I discovered that I still

had my escape equipment and emergency food rations in a small tin

in my pocket, and a copy of the wireless frequencies for the previous

night also. I extracted these articles cautiously and

awaiting the opportunity, flung them far out into the marshes.

My action, thank God, went unnoticed.

Eventually we arrived in a small village and drove up to a

dilapidated two-storey building outside of which was flying the

largest flag that I have ever seen in my life. It was my first

sight of a Nazi war flag, with the big hooked cross, of which I was

destined to see many in the next few years. That cross was indeed

an ominous sign.

I was carried by two men into a small room where I was

searched thoroughly by an officer in a black uniform with a

swashtika armband (Gestapo) and given another drink of water.

His first words to me, spoken in perfect English, were, "For you

the war is over." I cringed visibly.

I was transferred from here about an hour later to another

centre or police station, in a Ford V-8 sedan which I took to have

been captured from the Allies in either France, Belgium or Holland.

To my very great surprise, I was taken on a stretcher into

a fairly large room where I met the other members of my crew who

were sitting about very dejected indeed. Colin Campbell,

our rear gunner, was also on a stretcher and had a very bad leg

wound from which he was two months later to contract gangrene and

die.

In the few short spaces of time when we were left along, I

was able to learn something of the events which followed after I

left the aircraft by parachute. The crew consisted of three Australians

and two Englishmen. It appears that I left the aircraft

at a height of somewhere between 700 and 1000 feet. Just after I

had jumped, the skipper noticed the water glinting below and decided

that he was too low for the rest of the crew to bail out, and

so had only one alternative, to crash land on the beach.

By magnificent judgement and remarkable skill - this learned

from the other members of the crew - he manoeuvred the aircraft to

such a position as to make this crash landing possible, and despite

the fact that the starboard engine was on fire, the tail unit

damaged, wheels and flaps down, and all instruments damaged, he

somehow managed to 'prang' on the beach after hitting the top of a

ridge and settled the aircraft on to the sand without further injury

to the remaining members of the crew.

Two of them then went off to find assistance for the rear

gunner, who, by this time, was in a serious state due to loss of

blood; whilst the other endeavoured to destroy the aircraft, maps,

etc. by fire. These actions were all highly commendable, especially

in view of the fact that it may well have been possible for

them to make good their escape had they not delayed.

From this Gestapo centre, the pilot and front gunner, who

6.

were uninjured, went off to a Stalag (Luft 3), and I was to meet

up with them again nearly eighteen months later at Stalag Luft 6.

The navigator, who had been grazed by a bullet, the rear gunner

and myself were taken by motor ambulance to the German Military

Hospital in Amsterdam, which, previous to the war, had been

the biggest general hospital in that city.

Then followed the most unforgettable period of my life.

I was stripped of all clothing by means of cutting open my uniform

down both sides with a pair of scissors, and was lifted out

of my battle tunic and underwear looking a very sorry sight indeed.

I was then wheeled into the operating theatre where there

were three tables and a large number of doctors and nurses, German

and Dutch, looking extremely businesslike in long white gowns.

I was placed on one table and strapped down so that I could not

raise even my shoulders. For some minutes I remained thus, and

then noticed a doctor and a couple of nurses preparing instruments

and laying them out on a wheel-table near my feet.

The very next instant the doctor put his hand on my right

leg and I felt a searing pain burn right through my body. He had

made an incision in my leg without administering an anaesthetic!

I let out such a scream of agony as could have been heard throughout

Holland, and rocked and rolled the operating table till it was

on the verge of rolling over. A Dutch nurse, (Red Cross), whom I

later learned was the only person there who could speak English,

and she only about twenty words, came and tried to pacify me, saying

"I am your friend." I forgot my manners completely and said,

"It b...... well looks like it, when you let those b...... b...... do

that!" She appeared however not to understand, but eventually by

using a sign language I was able to to convey my meaning to her. I

then received an injection in the back which paralysed my body from

the hips down.

Whether this anaesthetic was overlooked or forgotten about

or forgotten purposely, I cannot say; but my opinion that it was

disregarded purposely will always be most decided. It was well

known that the Germans were short of medical supplies, and I shall

always believe that it was not the policy at the time to waste

their scanty reserves on prisoners of war.

I had previously been x-rayed from my head to my toes, but

after the shrapnel had been removed from my legs and the bones set

I was taken up to a room which contained five beds. These beds

were occupied by our navigator and rear gunner and two other R.A.F

chaps who had been shot down the previous night.

I had only just been placed on the bed and the stretcher

taken away when they returned with it and took me down to the

operating theatre once more. It seems that they had forgotten

about the small splinters of shrapnel in my hands, arms and head;

and now, after shaving off all my hair, they set to work to dig

these pieces out. They were removed without further anaesthetic.

I shall never forget the awful crunching noise as pieces of shrapnel

were recovered from my head, and I was many times to relive

that period in the operating theatre again in dreams, nightmares

and in my thoughts.

On the next seven days I have little recollection. I was

in a hazy stupor most of the time and can only recall one or two

incidents which happened in that time even though I was taken out

of the room every morning to have my "scratches" washed and redressed.

An illustration of my complete absence of mind can be

gained from the fact that on one occasion I threw off the coma long

enough to ask for the time of day, (all this was said to me afterwards

by the navigator) and after being told that it was 9.30 a.m,

I asked, "is it today or yesterday?"

When I eventually became sufficiently sensible to be aware

of events which were taking place, I found that I had been placed

in the care of a German Luftwaffe hospital orderly, who, l must

7.

say, treated me with every sympathy and, despite the language difficulty,

with every understanding. It was he who took me every

day to the surgery-cum-bathroom and changed dressings - all paper

bandages were used - and washed me. As, at this stage, I had my

right leg in plaster to the knee, my left leg in removable splints

my head bandaged so as to leave uncovered the eyes, nose and mouth

only, and both hands swathed in paper bandages, it can be seen

that I was in a pretty hopeless state in so far as helping myself

was concerned.

About this time, I can remember the German doctor bringing

in a number of leeches in a bottle which were eventually used

on the rear gunner's leg - he was sleeping in a bed which ran at

right angles to the foot of my own - in an endeavour to suck the

poisonous gangrene from his leg. This, however, failed and

shortly after he was removed from our room, operated upon to the

extent of having his right leg amputated above the knee, and then

placed in another ward. As far as I can remember he was never

fully conscious from the time he entered hospital and thereafter

he became lower and lower in health. I saw him for the last

time when I was wheeled into his ward one morning on a stretcher

by my medical orderly. I made some few cheering remarks, but I

don't believe that he really understood them or recognised me,

although he made some sort of reply. He was taken soon afterwards

to Dulag-Luft, and from there to a civilian hospital where

he died two months after the date of our being shot down. We

received this information by letter in Stalag-Luft 6 almost

eighteen months later.

I remained at Amsterdam approximately three weeks and was

taken then, along with the navigator and several other prisoners

of war, who had arrived in the interim, to Dulag-Luft - an interrogation

centre just on the outskirts of the city of Frankfurt-on-Main.

It was during this journey that one of the most amusing

incidents in all my P.O.W. experience took place. Upon leaving

Amsterdam, I was given a German Luftwaffe uniform to wear as all

my own clothing had been destroyed by the hospital authorities.

Whilst travelling in the train we were accommodated in two reserved

third class compartments, and I was placed as a lying-patient on

one of the seats. At a big rail centre, I forget the name, we

had to change trains and I was handed through the window and

placed in a recumbent position on the station platform. Two

German Red Cross nurses brought us blankets and these were placed

over me. The rest of the British prisoners of war were standing

under guard about ten yards further down the platform, whilst I

was left entirely on my own. Presently a crowd of civilians,

recognising the German uniform I was wearing, gathered around me

and began to jabber away in their own tongue, presumably offering

me sympathy. As I was terrified that they would discover their

mistake and give me an unpleasant time, I had to feign an agonised

look and stage a mock faint so that I was not forced to speak and

thereby reveal my identity. Meanwhile, the other British lads

were being spat upon and given very black, spiteful looks only a

few yards away!

We were taken in a motor transport from Frankfurt Station

to the prison hospital, after being given a bowl of potato soup, of

which I was later to see a good deal. I was there placed in a

single room and left to my resources for four days. The only

person I saw in this time was a German medical orderly who brought

me food, water, urine bottles etc., and carefully locked the door

upon his entry and exit. On the fifth day, two smartly dressed

German air force officers came into the room. They offered me

American and British cigarettes, and in perfect English, began to

ask me a lot of awkward questions. I gave them my name, rank

and number, and the address of next-of-kin; and answered "I

forget" to all other questions.

They were particularly interested to know, or verify, the

number of my squadron, the name of the commanding officer, where I

trained, when I left home, and a thousand other things, and by the

8.

time they were finished questioning, my head was pounding. Eventually

they left. Whether I gave any information away by looks of

surprise, by the flick of an eye, or by any other action, I shall

never know. They appeared however to leave in a very irritable

mood and this raised my spirits no end.

I was then transferred to a hospital ward in which were

five or six other R.A.F. chaps. They were all in high spirits

and were extremely cautious in talking lest they gave away any information.

Those few who were able to move around played the

game magnificently and waited hand and foot on the less fortunate

ones who were confined to bed.

It was here that the spirit of comradeship prevalent in

P.O.W. camps - so magnificent and praiseworthy - was first revealed

to me; and I was later to admire this quality in the many

fine fellows that I met - all of whom had gone through their own

frightening experiences - and I determined to do my best to

emulate their fine spirit and example. As I grew to learn how

very fortunate I was compared with many others of the fellows,

this quality eventually became quite natural in me.

The medical treatment at Dulag-Luft was an absolute disgrace.

The German doctor called only twice a week, and unless

one's limb was practically falling off, as many were, dressings

were renewed but once a week. When the order came that we were

to move to Obermassfeld, a P.O.W. hospital staffed with British

P.O.W. doctors and medical personnel, the change appeared to be

for the better.

I arrived there about the end of July, 1942 and had

several operations for the removal of further pieces of shrapnel,

bone etc. before moving to another P.O.W. hospital at Wasungen,

when the wounded Canadian soldiers began to arrive after the

Dieppe debacle about three weeks later.

Whilst the actual medical attention at Obermassfeld was

excellent, the organisation on the British side was a complete

disgrace. The actual hospital was equipped with a kitchen, but

no cooked food was available apart from the midday meal, which

consisted of potato or barley soup provided by the Germans. The

R.A.M.C. medical orderlies were uncivil and selfish and more interested

in looking after themselves than the patients in their

care. Although this was most noticeable - a blind man could have

seen it - the R.A.M.C. medical officers made little or no attempt

to put things right. Individually the doctors did magnificent

work with poor equipment, but this did not atone for the complete

disregard of other things which could have made life more easy and

pleasant for all concerned.

The German Kommandant was a strict disciplinarian. His

hospital guards and medical orderlies made life almost unbearable

with their continual spying on the prisoners, their repeated searchings

of our few meagre belongings, and the imposing of childish

restrictions on such things as smoking, on hours when patients

could walk here or sit there etc. etc. but despite all this, the

morale of the prisoners was gloriously high and no indication was

ever given that they "couldn't take it." In fact, many subtle

ways were found to annoy the Germans and to make their task difficult

and objectionable. The German Kommandant was a typical

Prussian Nazi; the punishments that he awarded were hardly in accordance

with the dictates of justice and he appeared to be hated

by the Germans under his charge as well as by the prisoners of war.

His actual control and organisation of the hospital however, was

particularly businesslike and he was, thank God, very strict about

matters pertaining to hygiene.

At Wasungen, a P.O.W. hospital for French and Russians

mostly suffering from T.B. and other chest complaints, I met two

Australian doctors and two medical orderlies, and consequently,

had few complaints to make regarding treatment. There were only

12 British patients there altogether and the doctors were very

pleased to have someone there with whom they could speak in their

own language. There was, therefore, no rank barrier whatsoever.

Sam scott

Sam scottThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.