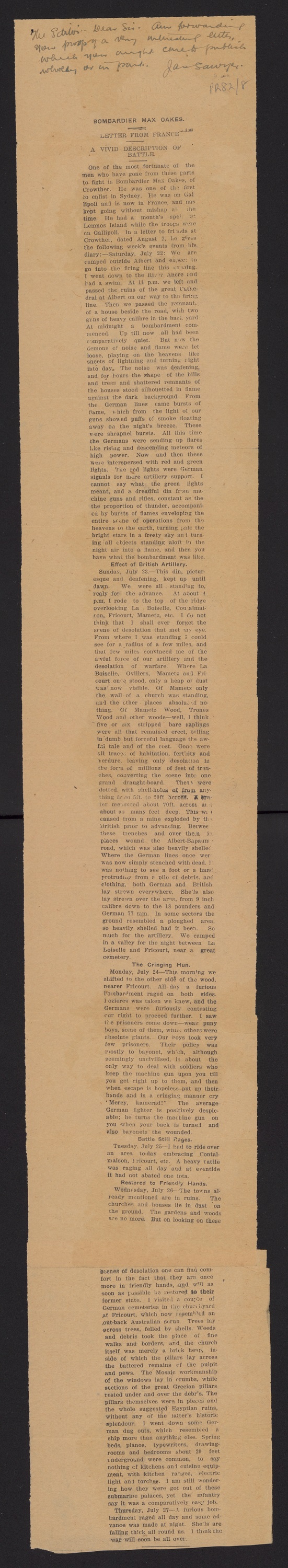

Typed letter forwarded from Jas Sawer to the Editor of the Sydney Morning Herald

The Editor—Dear Sir, Am forwarding

now proposing a very interesting letter

which you aught care to publish

wholly or in part. Jas. Sawyer.

PR82/8

BOMBARDIER MAX OAKES.

LETTER FROM FRANCE

A VIVID DESCRIPTION OF

BATTLE

One of the most fortunate of the

men who have gone from these parts

to fight is Bombardier Max Oakes, of

Crowther. He was one of the first

to enlist in Sydney. He was on Gallipoli

and is now in France and has

kept going without mishap at the

time. He had a month's spell at

Lemnos Island while the troops were

on Gallipoli. In a letter to friends at

Crowther, dated August 2, he gives

the following week's events from his

diary:—Saturday, July 22: We are

camped outside Albert and expect to

go into the firing line this evening.

I went down to the River Ancre and

had a swim. At 11 p.m. we left and

passed the ruins of the great Cathedral

at Albert on our way to the firing

line. Then we passed the remnant

of a house beside the road, with two

guns of heavy calibre in the back yard

At midnight a bombardment commenced.

Up till now all had been

comparatively quiet. But now the

demons of noise and flame were let

loose, playing on the heavens like

sheets of lightning and turning night

into day. The noise was deafening

and for hours the shape of the hills

and trees and shattered remnants of

the houses stood silhouetted in flame

against the dark background. From

the German lines came bursts of

flame, which from the light of our

guns showed puffs of smoke floating

away on the night's breeze. These

were shrapnel bursts. All this time

the Germans were sending up flares

Like rising and descending meteors of

high power. Now and then these

were interspersed with red and green

lights. The red lights were German

signals for more artillery support. I

cannot say what the green lights

meant, and a dreadful din from machine

guns and rifles, constant as the

the proportion of thunder, accompanied

by bursts of flames enveloping the

entire scene of operations from the

heavens to the earth, turning pale the

bright stars in a frosty sky and turning

all objects standing aloft in the

night air into flame, and then you

have what the bombardment was like.

Effect of British Artillery.

Sunday, July 23.—This din, picturesque

and deafening, kept up until

dawn. We were all standing to,

ready for the advance. At about 4

p.m. I rode to the top of the ridge

overlooking La Boiselle, Contalmaiton,

Fricourt, Mametz, etc. I do not

think that I shall ever forget the

scene of desolation of that met my eye.

From where I was standing I could

see for a radius of a few miles, and

that few miles convinced me of the

desolation of warfare. Where La

Boiselle, Ovillers, Mametz and Fricourt

once stood, only a heap of dust

was now visible. Of Mametz only

the wall of a church was standing,

and the other places absolute nothing.

Of Mametz Wood, Trones

Wood and other woods—well, I think

five of six stripped bare of saplings

were all that the remained erect, telling

in dumb but forceful language the awful

tale and of the cost. Gone were

all traces of habitation, fertility and

verdure, leaving only desolation in

the form of millions of feet of trenches,

converting the scene into one

grand draught-board. There were

dotted with shell-holes of from any-

thing from 5ft. to 20ft. across. A crater

measured about 70 feet across and

about as many feet deep. this was

caused from a mine exploded by the

British prior to advancing. Between

these trenches and over them in

places wound the Albert-Bapaume

road, which was also heavily shelled.

Where the German lines once were

was now simply stenched with dead. It

was nothing to see a foot or a hand

protruding from a pile of debris and

clothing, both German and British

lay strewn everywhere. She is also

lay strewn over the area, from 9 inch

calibre down to the 18 pounders and

German 77 mm. In some sector the

ground resembled a ploughed area,

so heavily shelled had it been. So

much for the artillery. We camped

in a valley for the night between La

Loiselle and Fricourt, near a great

cemetery.

The Cringing Hun.

Monday, July 24—This Morning we

shifted to the other side of the wood,

nearer Fricourt. All day a furious

Bombardment raged on both sides

Pozieres was taken we knew, and the

Germans were furiously contesting

cur right to proceed further. I saw

the prisoners come down—weak puny

boys, some of them, while others were

absolute giants. Our boys took very

few prisoners. Their policy was

mostly to bayonet, which, although

seemingly uncivilised, is about the

only was to deal with soldiers who

keep the machine gun on you till

you get right up to them, and then

when escape is hopeless put up their

hands and in cringing manner cry

'Mercy, kamerad!' The average

German fighter is positively despicable;

he turns the machine gun on

you when your back is turned and

also bayonets the wounded.

Battle Still Rages

Tuesday, July 25—I had to ride over

an area to-day embracing Contalmaison,

Fricourt, etc. A heavy battle

was raging all day and at eventide

it has not abated one iota.

Restored to Friendly Hands

Wednesday, July 26—the towns already

mentioned are in ruins. The

churches and houses lie in dust on

the ground. The gardens and woods

are no more. But on looking on these

scenes of desolation one can find comfort

in the fact that they are once

more in friendly hands, and will as

soon as possible be restored to their

former state. I visited a couple of

German cemeteries in the churchyard

at Fricourt, which now resembled an

out-back Australian scrub. Trees lay

across trees, felled by shells. Weeds

and debris took the place of the fine

walks and borders, and the church

itself was merely a brick heap. Inside

of which the pillars lay across

the battered remains of the pulpit

and pews. The Mosaic workmanship

of the windows lay in crumbs, while

sections of the great Grecian pillars

rested under and over the debris. The

pillars themselves were in pieces and

the whole suggested Egyptian ruins

without and of the latter's historic

splendour. I went down some German

dug outs, which resembled a

ship more than anything else. Spring

beds, pianos, typewriter, drawing

rooms and bedrooms about 20 feet

underground were common, to say

nothing of kitchens and cuisine equipment,

with kitchen ranges, electric

light and torches. I am still wondering

how they were got out of these

submarine palaces, yet the infantry

say it was a comparatively easy job.

Thursday, July 27—A furious bombardment:

raged all day and some advance

was made at night. Shells are

falling thick all round us. I think the

war will soon be all over.

Sam scott

Sam scottThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.