Typescript copy of diary entries of Percy Wellesley Chapman, 1 July 1915 to 30 June 1916 - Part 4

November 28th.

To-day is my birthday and is Sunday, so I will consider

the circumstance merits an entry in my diary. In fact

it is rather a novel way of spending a birthday. Of

yore should I be at home, I would have been ushered into

the breakfast table in state to inspect the huge bundle

of presents on my plate. But to-day I began the Sabbath

at 12 o'clock midnight, rifle in hand, creeping out into

the snow and cold on patrol work. Outside the

dug-out

while I write, sitting in my blankets, the snow flakes

are chasing each other towards the earth, where they

flitter about looking for the most suitable place to

settle. To-day is Thursday and nearly all traces

of the snow have gone. In the sheltered crevices of the

hills it still lingers, just isolated patches here and

there as if it were unwilling to make way for sunny

days. Gallipoli can be cold sometimes, for instance

a couple of mornings ago after we had finished breakfast,

the tea left in the cups and billy froze into a solid

mass, but now peace and sunshine have taken possession;-

except for the crack of rifles in the distance everything

is still. A hospital boat lying at anchor about three

miles out to sea is awaiting its load of sick and wounded--

sometimes when it is cold and miserable a wounded man

is envied because he can go out to a comfortable bed.

Bang! a shrapnel has just burst at Casualty Point right

on the water's edge, too low to do any damage I fancy.

These shells come from a gun known as "Beachy Bill"

concealed somewhere in what is known as the olive grove,

but so far our guns have not been able to silence it, the

number of victims fallen to Beachy Bill total over a

-31-

thousand or more. Three men have been told off as

permanent bomb-throwers - Jack Holland, Betts and myself.

With the instructions issued about throwing, it mentions

that only the bravest and best men must be chosen for

this branch. I don't know whether to feel flattered

or not. I suppose they have chosen the first three

that struck their notice. I am a permanent patrol

member also, not that that signifies anything,but in the

patrol work a man has scope for a little freedom of

thought and action and that is what I like. In the

trenches you have a much easier and warmer time, a good

deal more sleep also, but non-coms are always there and

officers to be "halted" and allowed to pass; a fellow

is only a machine more or less in the trench, once he

creeps out over the parapet towards the Turks he has to

think. I have to-night off and am glad of it too.

During the first part of the cold snap one of the boots

that I was wearing had had some slits made in the toe as

that member of my foot had a habit of pushing itself

forward and becoming sore, consequently when the snow and

slush came it filtered through. I had those boots and

socks on for about fort-eight hours, the result is that

since then my foot has a habit of throbbing. It will be

perfectly well by to-morrow and does not need any sympathy

however. I have become an out-and-out pincher, and

have become quite proud of the accomplishment. Once I

heard a story about two soldiers who went through the

Crimean War comfortably and it was done just by looking

after themselves. Well, I'm going to follow their example

The day after the snow we were sent down to the beach to

get some trousers for the regiment; the whole beach down

-32-

there is packed with cases of all sorts of things such

as boots, leggings, clothes, eatables, etc., but although

the commissariat do their duty and have the staff stuff

here ready, the military authorities never issue it

until too late, and if a fellow helps himself he is apt

to get two years hard. However I wanted a pair of

boots, and as luck would have it "Beachy Bill" started

to shell the clothes, so that every one was ordered to

leave. The place is full of military police, but as a

shell lobbed near a box of leggings and these chaps

ducked for safety, I followed their example and ducked

also, but to the box where I secured a good pair. I also

got an overcoat, a pair of boots, a waterproof cape, and

never felt so happy as when I got home and changed into

dry boots and socks. I heard that during the snow there

were about eleven cases of frost-bite, a good many

occurred amongst the Gurkhas. Yesterday afternoon a

rumour spread that at half-past three a cannonading demonstration

would be given against Snipers Nest. Snipers

Nest I may say is a Turkish post, a pointed ridge which

juts out towards our position about four hundred yards

from our trenches. I made my way up to our Snipers

post that I could have a good view. I expect you have

never heard six-inch shells bursting in earnest. They

were lyddite and great clouds of green smoke rose as they

thundered on to this narrow neck of land. The first

shell hit a little wide among some green brush, and dis

turbed a flock of grouse, one fluttered with a broken

wing into the Turkish trench. The second shell also

fell short, but the third crashed right on to the posi¬

tion through a bank of earth and burst in a tunnel. The

whole hill seemed to shake as these high explosives

-33-

burst, and the sound seemed to crash against our ears.

We could hear pieces of broken shell humming over our

heads. As soon as this gun had found the range two of

them opened fire, and four shells in succession crashed

home. I don't know what became of the Turks. I didn't

see any legs or arms flying skywards, but perhaps they

had withdrawn to a safe position after the first shell.

Jack Holland was sent on guard to Embros a couple of

weeks ago, and returned the day before yesterday with a

nice supply of provisions such as six tins of milk, two

bottles of bovril, some tins of salmon and a bag of

oranges and potatoes, and last but not least about ten

shillings' worth of chocolates. I suppose you think it

strange that we spend so much on chocolates, but you

really have no idea of the craving for something of that

sort that takes possession of a fellow here. Of course

ten shillings does not buy very much, a penny stick

costs as much as sixpence here; huge profits are made

by some of the sailors on the hospital ships, they buy

things such as chocolates, dried figs, tinned fish, etc.,

at Malta or Alexandria where prices are normal and

retail, then sell them here at three or four times their

original price. Squadron cooking has started now, and

this means that we don't get the dainty dishes, or the

amount of food that we had when doing our own. And

lately also, owing to the rough weather and no stores

being able to be landed we have been on half rations.

But it didn't affect us much - I have rigged up a little

stove in the wall of the dug-out, and on this we cook

porridge in the morning made from ground biscuits, and

in the good times we laid in a supply of bully beef and

-34-

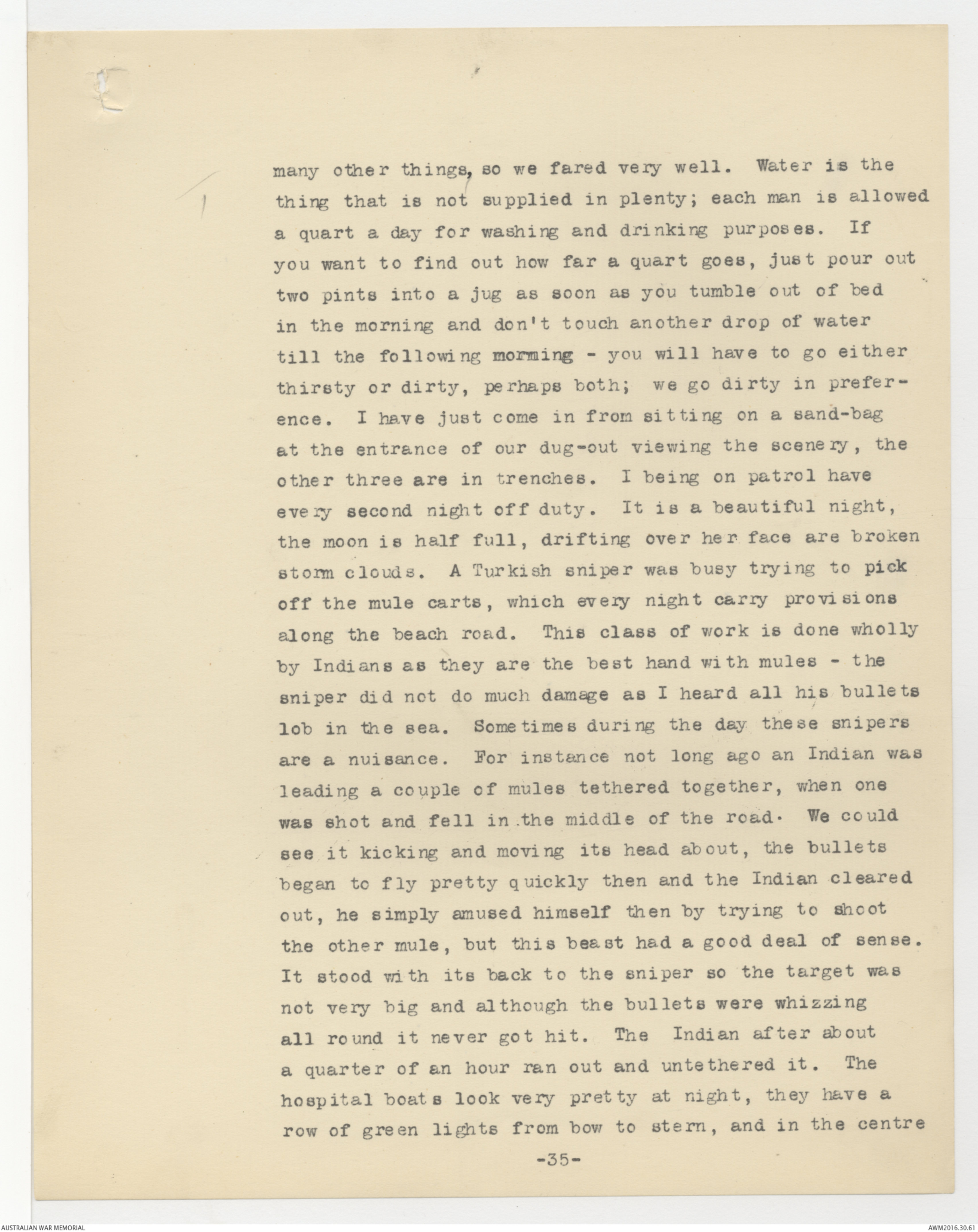

many other things, so we fared very well. Water is the

thing that is not supplied in plenty; each man is allowed

a quart a day for washing and drinking purposes. If

you want to find out how far a quart goes, just pour out

two pints into a jug as soon as you tumble out of bed

in the morning and don't touch another drop of water

till the following morming - you will have to go either

thirsty or dirty, perhaps both; we go dirty in

preference.

I have just come in from sitting on a sand-bag

at the entrance of our dug-out viewing the scenery, the

other three are in trenches. I being on patrol have

every second night off duty. It is a beautiful night,

the moon is half full, drifting over her face are broken

storm clouds. A Turkish sniper was busy trying to pick

off the mule carts, which every night carry provisions

along the beach road. This class of work is done wholly

by Indians as they are the best hand with mules - the

sniper did not do much damage as I heard all his bullets

lob in the sea. Sometimes during the day these snipers

are a nuisance. For instance not long ago an Indian was

leading a couple of mules tethered together, when one

was shot and fell in the middle of the road. We could

see it kicking and moving its head about, the bullets

began to fly pretty quickly then and the Indian cleared

out, he simply amused himself then by trying to shoot

the other mule, but this beast had a good deal of sense.

It stood with its back to the sniper so the target was

not very big and although the bullets were whizzing

all round it never got hit. The Indian after about

a quarter of an hour ran out and untethered it. The

hospital boats look very pretty at night, they have a

row of green lights from bow to stern, and in the centre

-35-

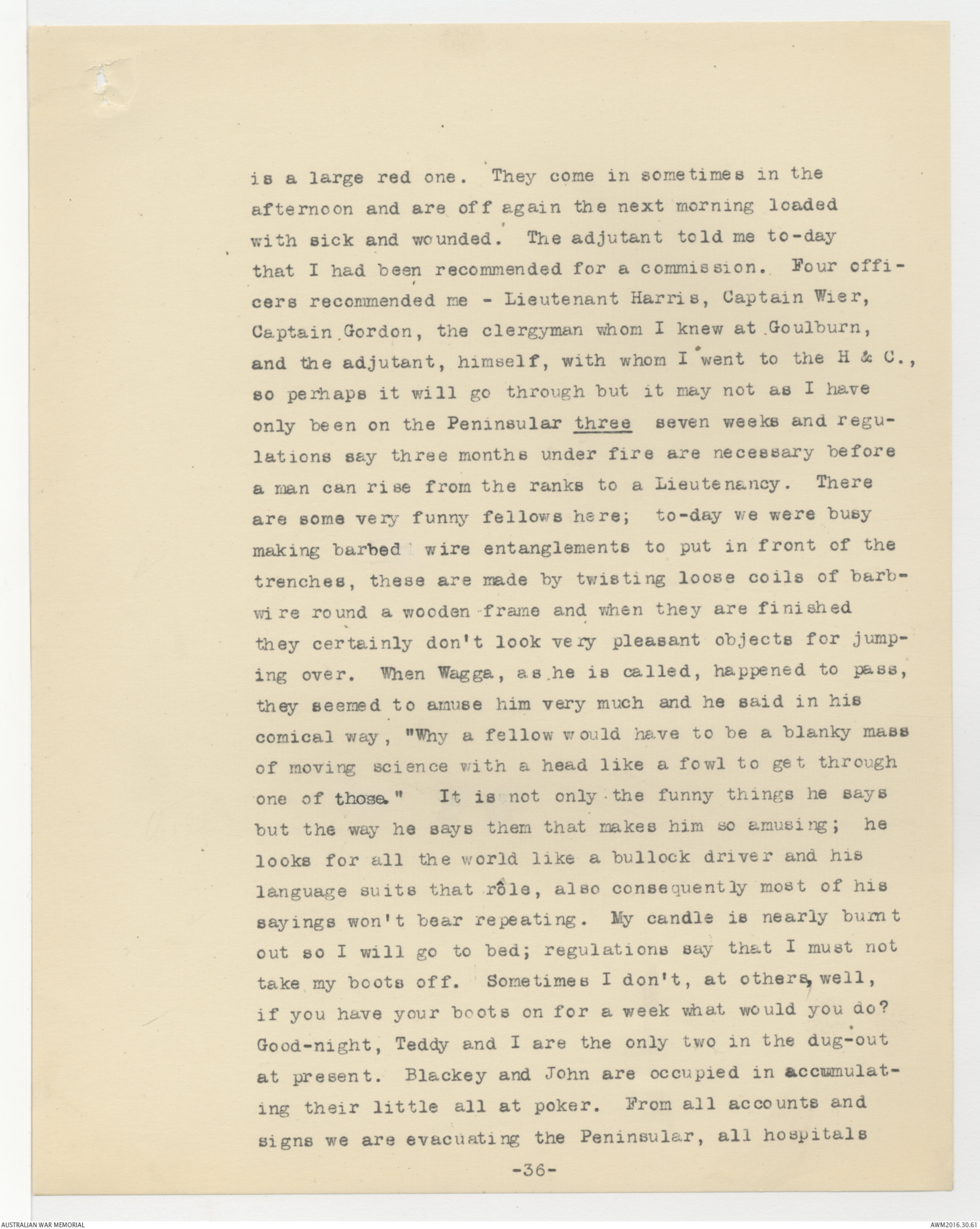

is a large red one. They come in sometimes in the

afternoon and are off again the next morning loaded

with sick and wounded. The adjutant told me to-day

that I had been recommended for a commission. Four officers

recommended me - Lieutenant Harris, Captain Wier,

Captain Gordon, the clergyman whom I knew at Goulburn,

and the adjutant, himself, with whom I went to the H & C.,

so perhaps it will go through but it may not as I have

only been on the Peninsular three seven weeks and regulations

say three months under fire are necessary before

a man can rise from the ranks to a Lieutenancy. There

are some very funny fellows here; to-day we were busy

making barbed wire entanglements to put in front of the

trenches, these are made by twisting loose coils of barbwire

round a wooden frame and when they are finished

they certainly don't look very pleasant objects for jumping

over. When Wagga, as he is called, happened to pass,

they seemed to amuse him very much and he said in his

comical way, "Why a fellow would have to be a blanky mass

of moving science with a head like a fowl to get through

one of those" It is not only the funny things he says

but the way he says them that makes him so amusing; he

looks for all the world like a bullock driver and his

language suits that role, also consequently most of his

sayings won't bear repeating. My candle is nearly burnt

out so I will go to bed; regulations say that I must not

take my boots off. Sometimes I don't, at others, well,

if you have your boots on for a week what would you do?

Good-night, Teddy and I are the only two in the dug-out

at present. Blackey and John are occupied in accumulating

their little all at poker. From all accounts and

signs we are evacuating the Peninsular, all hospitals

-36-

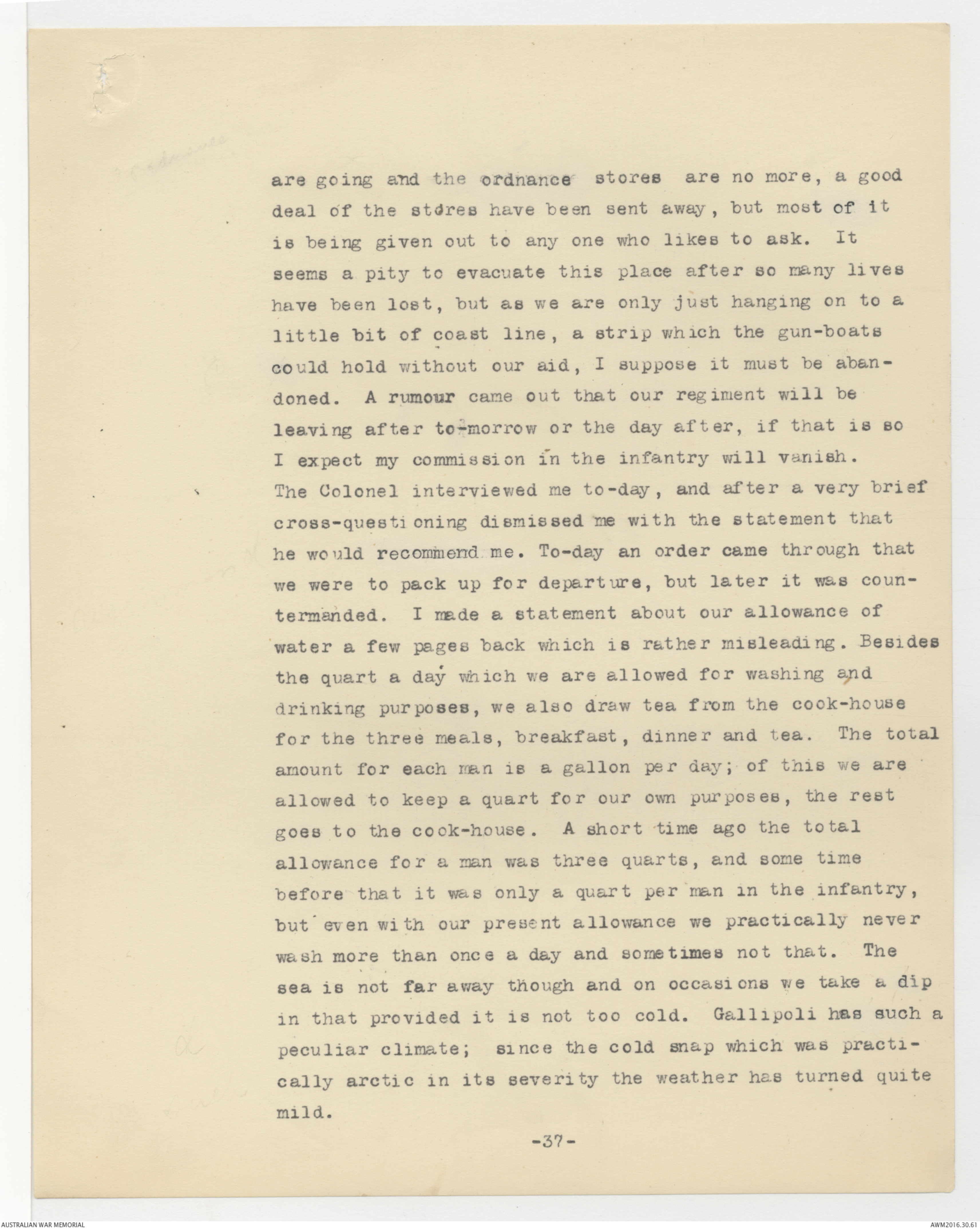

are going and the ordnance stores, are no more, a good

deal of the stores have been sent away, but most of it

is being given out to any one who likes to ask. It

seems a pity to evacuate this place after so many lives

have been lost, but as we are only just hanging on to a

little bit of coast line, a strip which the gun-boats

could hold without our aid, I suppose it must be abandoned.

A rumour came out that our regiment will be

leaving after tomorrow or the day after, if that is so

I expect my commission in the infantry will vanish.

The Colonel interviewed me to-day, and after a very brief

cross-questioning dismissed me with the statement that

he would recommend me. To-day an order came through that

we were to pack up for departure, but later it was countermanded.

I made a statement about our allowance of

water a few pages back which is rather misleading. Besides

the quart a day which we are allowed for washing and

drinking purposes, we also draw tea from the

cook - house

for the three meals, breakfast, dinner and tea. The total

amount for each man is a gallon per day; of this we are

allowed to keep a quart for our own purposes, the rest

goes to the cook-house. A short time ago the total

allowance for a man was three quarts, and some time

before that it was only a quart per man in the infantry,

but even with our present allowance we practically never

wash more than once a day and sometimes not that. The

sea is not far away though and on occasions we take a dip

in that provided it is not too cold. Gallipoli has such a

peculiar climate; since the cold snap which was practically

arctic in its severity the weather has turned quite

mild.

-37-

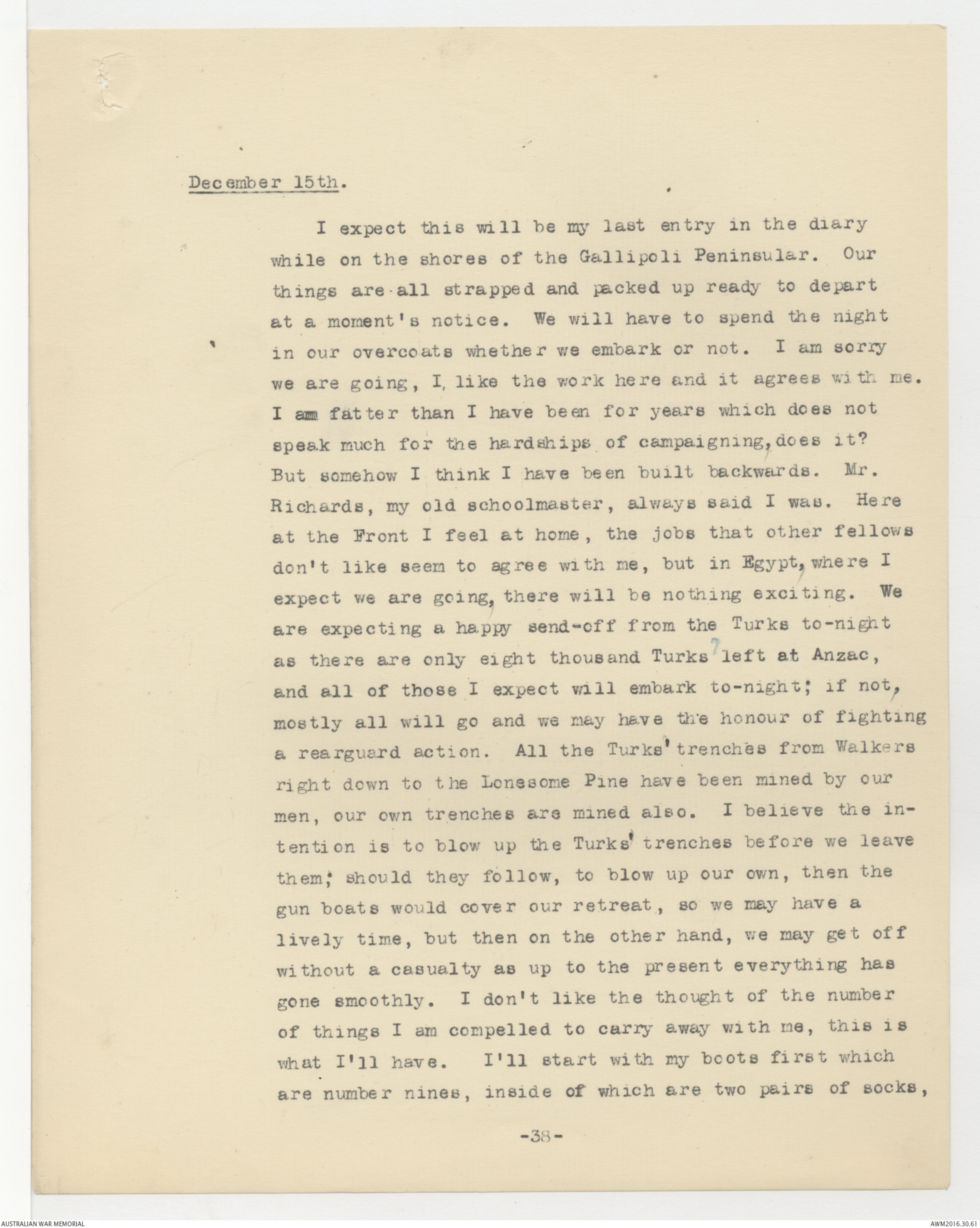

December 15th.

I expect this will be my last entry in the diary

while on the shores of the Gallipoli Peninsular. Our

things are all strapped and packed up ready to depart

at a moment's notice. We will have to spend the night

in our overcoats whether we embark or not. I am sorry

we are going, I like the work here and it agrees with me.

I am fatter than I have been for years which does not

speak much for the hardships of campaigning, does it?

But somehow I think I have been built backwards. Mr.

Richards, my old schoolmaster, always said I was. Here

at the Front I feel at home, the jobs that other fellows

don't like seem to agree with me, but in Egypt, where I

expect we are going, there will be nothing exciting. We

are expecting a happy send-off from the Turks

to-night

as there are only eight thousand Turks left at Anzac,

and all of those I expect will embark to-night; if not,

mostly all will go and we may have the honour of fighting

a rearguard action. All the Turks trenches from Walkers

right down to the Lonesome Pine have been mined by our

men, our own trenches are mined also. I believe the intention

is to blow up the Turks trenches before we leave

them; should they follow, to blow up our own, then the

gun boats would cover our retreat, so we may have a

lively time, but then on the other hand, we may get off

without a casualty as up to the present everything has

gone smoothly. I don't like the thought of the number

of things I am compelled to carry away with me, this is

what I'll have. I'll start with my boots first which

are number nines, inside of which are two pairs of socks,

-38-

then come underpants and trousers, cholera belt, trousers'

belt on which hangs a n automatic pistol and fifty rounds

of ammunition, a camera and field ambulance bandages,

singlet flannel shirt, cardigan jacket, tunic woolly

sheepskin vest, comforter, balaclava cap. overcoat

and

cap: then comes wet equipment and 150 rounds rifle,

two haversacks, one containing two tins bully beef, tin

of herring, biscuits, tin of jam one of milk and some

of cocoa and some soup tablets, the other containing razors

turn-out, tooth brush, towel, etc., water bottle; then

comes pack, which contains three pairs of socks, trousers

and tunic, putties - I am wearing leggings -towel,

singlet, underpants, spare cardigan jacket, photo films,

tobacco, on that comes two blankets, a rug and a waterproof sheet,

and a waterproof cape which I collared on the

beach, Amen. Something to fight a rearguard action on,

isn't it? But I have the pack and blankets tied on

separately so that they can be heaved into the nearest

ditch should the necessity arrive. I forgot to mention

that I have also a bayonet, and entrenching tool, quart

pot and dixy.

December 21st. Lemnos.

Well, we are off the Peninsular at last, but I must

leave the description and accounts of events till I am

in a more restful frame of mind. Just at present there

are eleven of us in a tent, the first tent since we left

Egypt just eight weeks ago. I intended making rather a

big entry but gentle sleep is hovering round, already she

has laid her soft hand upon some of the inmates of the

tent and their quite steady breathing reminds me that

perhaps I had better lay me down.

-39-

December 23rd.

Still Lemnos, but our stay here will be ended very

soon, Last night we embarked upon the HARORAPA, a

New Zealand boat of about twelve thousand tons. There

are over two thousand of us on board, a nice little

haul should we come across a submarine, but I must tell

you of the departure from Gallipoli. Sometime before

we left our squadron was changed from Number 1

subsection

trenches to No 11 subsection which means that instead

of manning the trenches in the gully we shifted to those

on top of the hill. I did not sample those but when on

duty I was on the outpost, a small trench about two

hundred yards in front of the main trenches. That night

of the evacuation the first light-horse had the honour

of leaving the trenches last. For days beforehand

troops had been leaving the Peninsular; one day we would

hear that there were eight thousand all told left to man

the trenches, next day the number would sink still lower

although we never heard the official numbers. The first

thing that really assured us we were going was the burning

of stores, etc. that could not be carted away;

thousands of pounds' worth of eatables and clothing had

to be destroyed, as the facilities for loading were so

poor. There are no harbours, and the rough sea breaks

straight upon the jetties taking all before it,

consequently time could not be given to much surplus material.

A great fire burned for two days before we left illuminating

the whole sky with its lurid light. I never

realised how wasteful war can be till I saw those great

heaps of food burning, with streams of melted bacon fat

running from them. Some of the stores-houses on the beach

-40-

Leanne mckenna

Leanne mckennaThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.