Typescript copy of diary entries of Percy Wellesley Chapman, 1 July 1915 to 30 June 1916 - Part 3

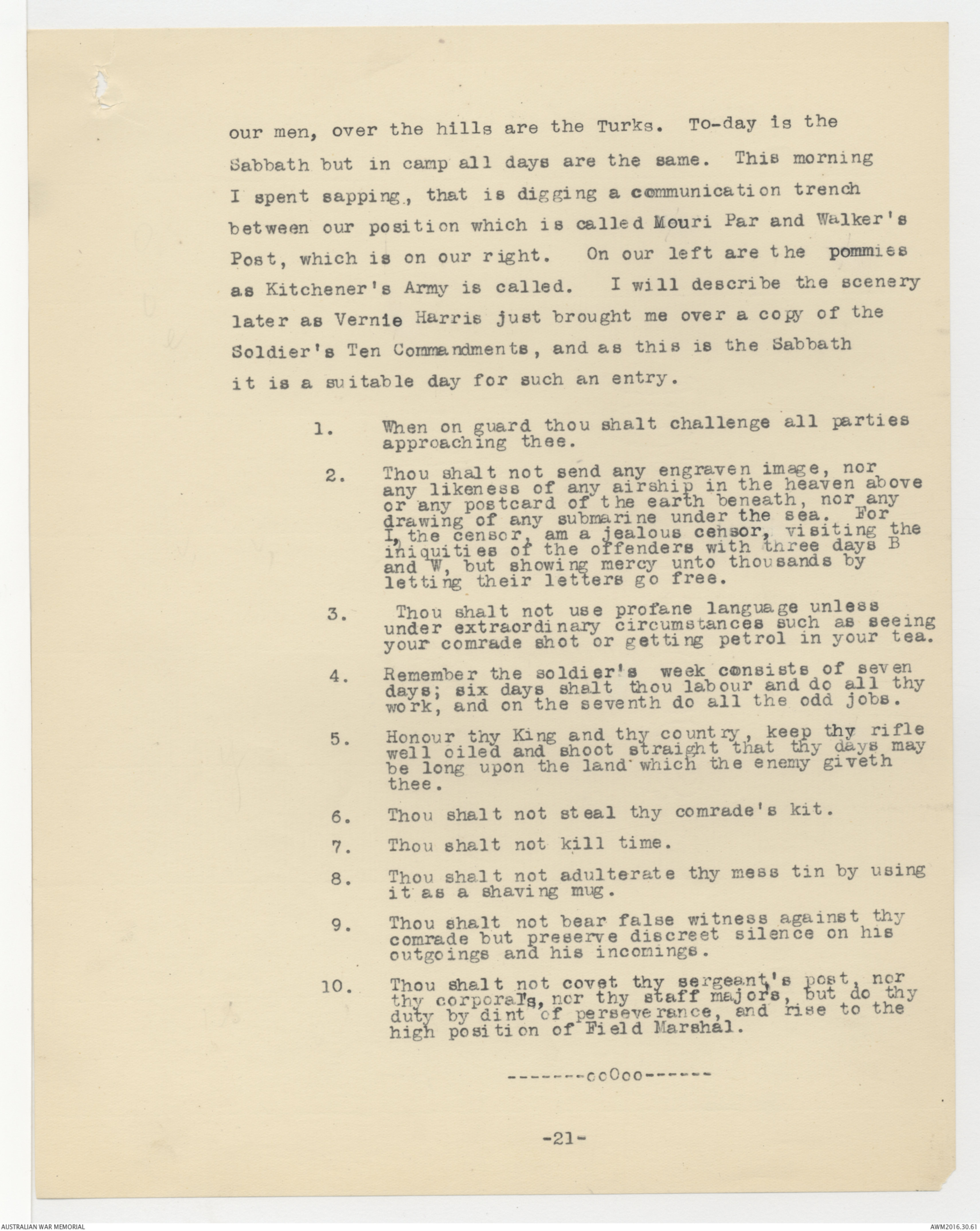

our men, over the hills are the Turks. To-day is the

Sabbath but in camp all days are the same. This morning

I spent sapping, that is digging a communication trench

between our position which is called Mouri Par and Walker's

Post, which is on our right. On our left are the pommies

as Kitchener's Army is called. I will describe the scenery

later as Vernie Harris just brought me over a copy of the

Soldier's Ten Commandments, and as this is the Sabbath

it is a suitable day for such an entry.

1. When on guard thou shalt challenge all parties

approaching thee.

2. Thou shalt not send any engraven image, nor

any likeness of any airship in the heaven above

or any postcard of the earth beneath, nor any

drawing of any submarine under the sea. For

I, the censor, am a jealous censor, visiting the

iniquities of the offenders with three days B

and W, but showing mercy unto thousands by

letting their letters go free.

3. Thou shalt not use profane language unless

under extraordinary circumstances such as seeing

your comrade shot or getting petrol in your tea.

4. Remember the soldier's week consists of seven

days; six days shalt thou labour and do all thy

work, and on the seventh do all the odd jobs.

5. Honour thy King and thy country, keep thy rifle

well oiled and shoot straight that thy days may

be long upon the land which the enemy giveth

thee.

6. Thou shalt not steal thy comrade's kit.

7. Thou shalt not kill time.

8. Thou shalt not adulterate thy mess tin by using

it as a shaving mug.

9. Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy

comrade but preserve discreet silence on his

outgoings and his incomings.

10. Thou shalt not covet thy sergeant's post, nor

thy corporal's, nor thy staff major's, but do thy

duty by dint of perseverance, and rise to the

high position of Field Marshal.

-21-

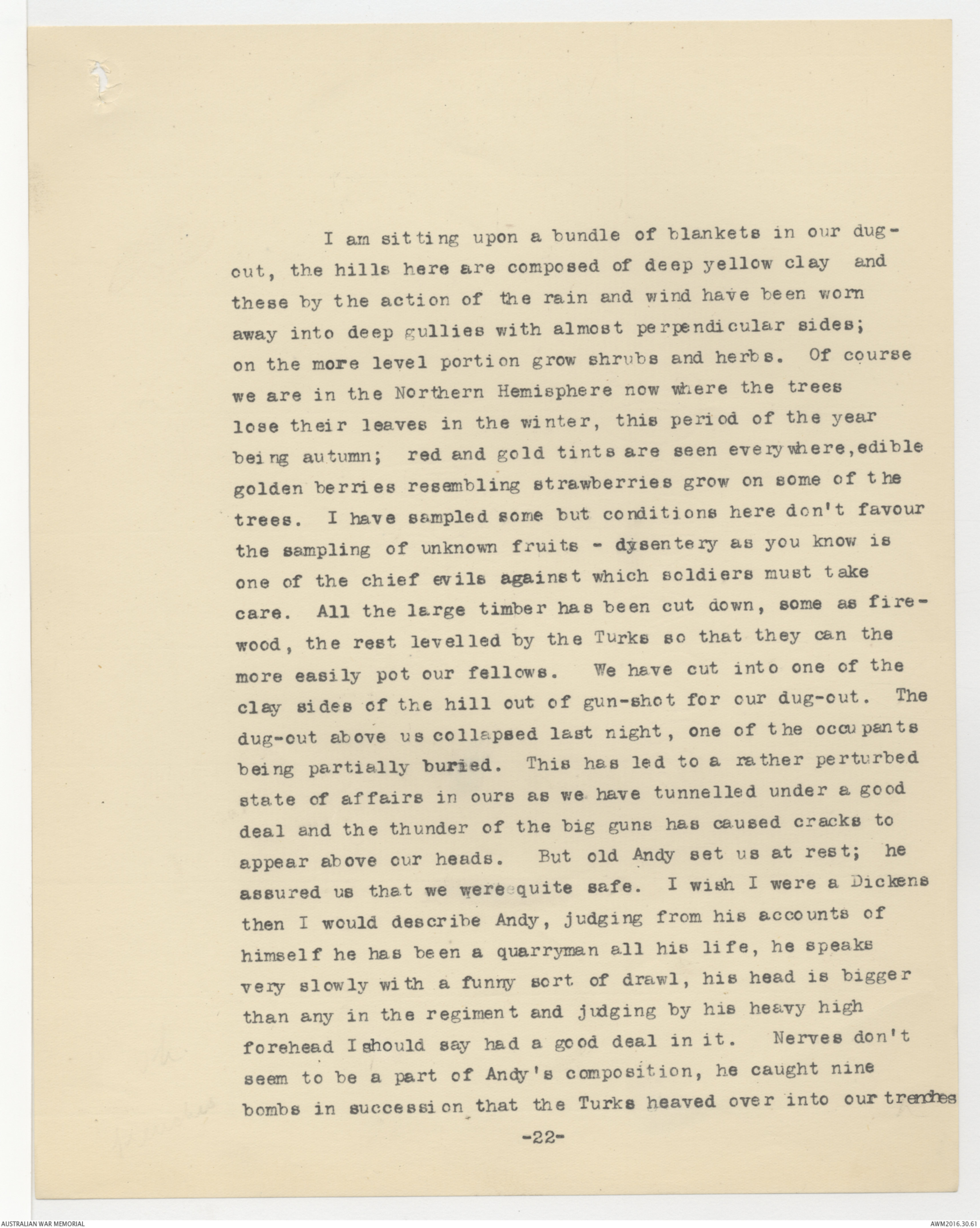

I am sitting upon a bundle of blankets in our dugout,

the hills here are composed of deep yellow clay, and

these by the action of the rain and wind have been worn

away into deep gullies with almost perpendicular sides;

on the more level portion grow shrubs and herbs. Of course

we are in the Northern Hemisphere now where the trees

lose their leaves in the winter, this period of the year

being autumn; red and gold tints are seen everywhere, edible

golden berries resembling strawberries grow on some of the

trees. I have sampled some but conditions here don't favour

the sampling of unknown fruits - dysentery as you know is

one of the chief evils against which soldiers must take

care. All the large timber has been cut down, some as firewood,

the rest levelled by the Turks so that they can the

more easily pot our fellows. We have cut into one of the

clay sides of the hill out of gun-shot for our dug-out. The

dug-out above us collapsed last night, one of the occupants

being partially buried. This has led to a rather perturbed

state of affairs in ours as we have tunnelled under a good

deal and the thunder of the big guns has caused cracks to

appear above our heads. But old Andy set us at rest; he

assured us that we were quite safe. I wish I were a Dickens

then I would describe Andy, judging from his accounts of

himself he has been a quarryman all his life, he speaks

very slowly with a funny sort of drawl, his head is bigger

than any in the regiment and judging by his heavy high

forehead I should say had a good deal in it. Nerves don't

seem to be a part of Andy's composition, he caught nine

bombs in succession that the Turks heaved over into our trenches

-22-

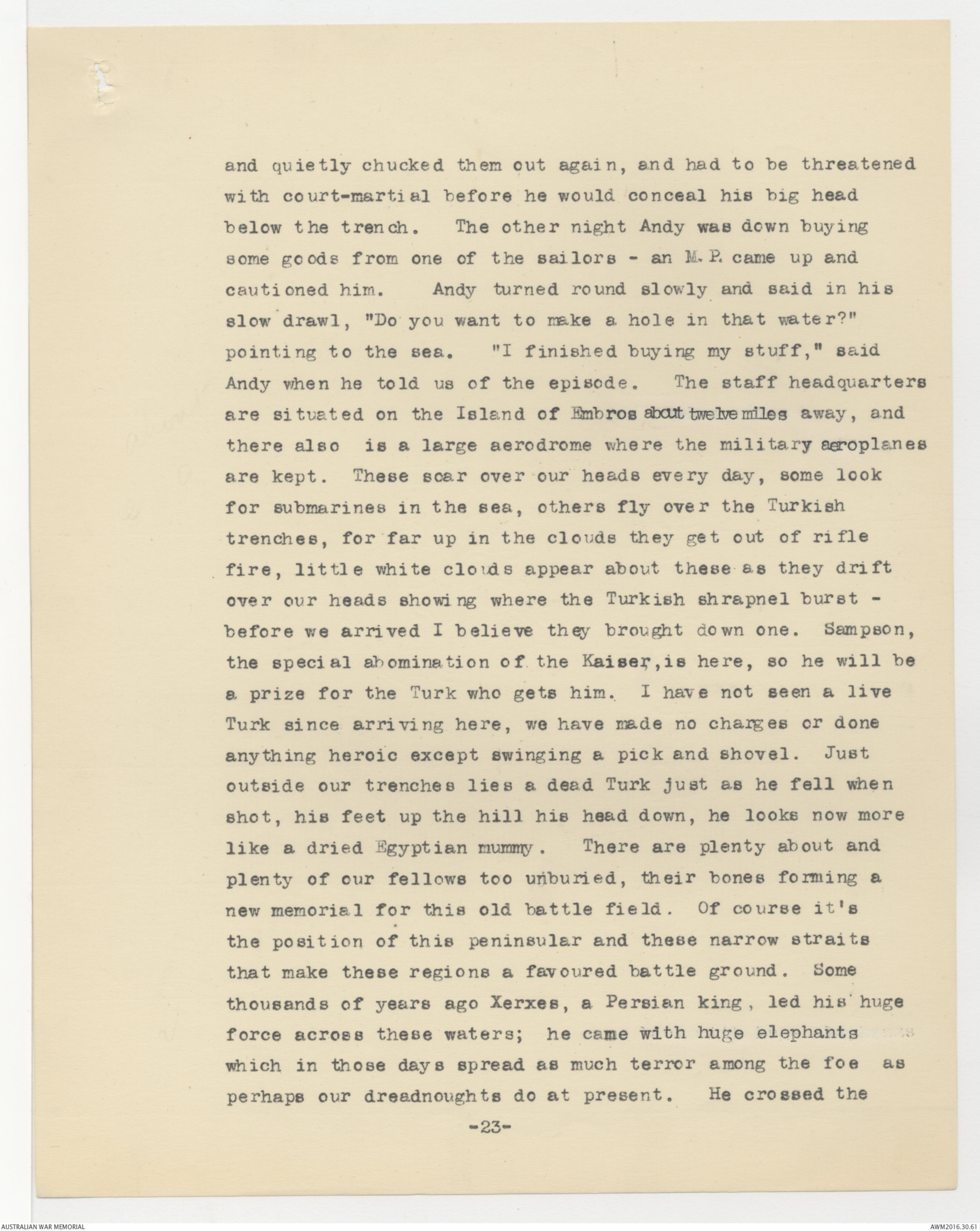

and quietly chucked them out again, and had to be threatened

with court-martial before he would conceal his big head

below the trench. The other night Andy was down buying

some goods from one of the sailors - an M.P. came up and

cautioned him. Andy turned round slowly and said in his

slow drawl, "Do you want to make a hole in that water?"

pointing to the sea. "I finished buying my stuff," said

Andy when he told us of the episode. The staff headquarters

are situated on the Island of Embros about twelve miles away, and

there also is a large aerodrome where the military aeroplanes

are kept. These soar over our heads every day, some look

for submarines in the sea, others fly over the Turkish

trenches, for far up in the clouds they get out of rifle

fire, little white clouds appear about these as they drift

over our heads showing where the Turkish shrapnel burst -

before we arrived I believe they brought down one. Sampson,

the special abomination of the Kaiser, is here, so he will be

a prize for the Turk who gets him. I have not seen a live

Turk since arriving here, we have made no charges or done

anything heroic except swinging a pick and shovel. Just

outside our trenches lies a dead Turk just as he fell when

shot, his feet up the hill his head down, he looks now more

like a dried Egyptian mummy. There are plenty about and

plenty of our fellows too unburied, their bones forming a

new memorial for this old battle field. Of course it's

the position of this peninsular and these narrow straits

that make these regions a favoured battle ground. Some

thousands of years ago Xerxes, a Persian king, led his huge

force across these waters; he came with huge elephants

which in those days spread as much terror among the foe as

perhaps our dreadnoughts do at present. He crossed the

-23-

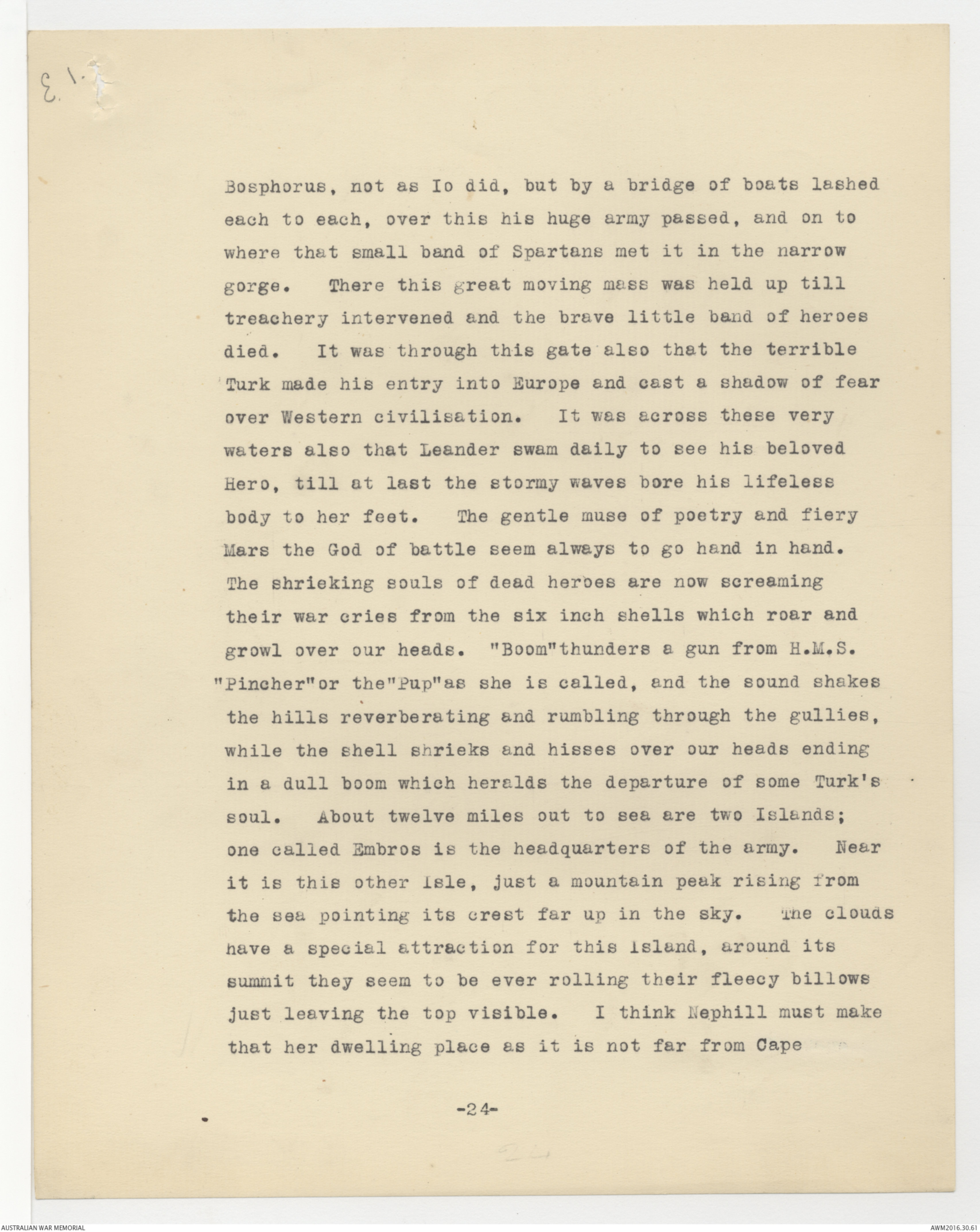

Bosphorus, not as Io did, but by a bridge of boats lashed

each to each, over this his huge army passed, and on to

where that small band of Spartans met it in the narrow

gorge. There this great moving mass was held up till

treachery intervened and the brave little band of heroes

died. It was through this gate also that the terrible

Turk made his entry into Europe and cast a shadow of fear

over Western civilisation. It was across these very

waters also that Leander swam daily to see his beloved

Hero, till at last the stormy waves bore his lifeless

body to her feet. The gentle muse of poetry and fiery

Mars the God of battle seem always to go hand in hand.

The shrieking souls of dead herbes are now screaming

their war cries from the six inch shells which roar and

growl over our heads. "Boom" thunders a gun from H.M.S.

"Pincher" or the "Pup" as she is called, and the sound shakes

the hills reverberating and rumbling through the gullies,

while the shell shrieks and hisses over our heads ending

in a dull boom which heralds the departure of some Turk's

soul. About twelve miles out to sea are two Islands;

one called Embros is the headquarters of the army. Near

it is this other Isle, just a mountain peak rising from

the sea pointing its crest far up in the sky. The clouds

have a special attraction for this Island, around its

summit they seem to be ever rolling their fleecy billows

just leaving the top visible. I think Nephill must make

that her dwelling place as it is not far from Cape

-24-

Helles where her daughter fell into the sea. This is

how Cape Helles and the Hellespont got their names.

I'm afraid this will have to wait as Jack Holland has

just come in with the rations for the day. We live very

well here, bacon is issued every day, rice, jam, treacle,

tinned milk occasionally, sugar, flour or bread, bully

beef and biscuits, and about every third day fresh meat;

currants are issued also. The biscuits are our special

amusement, they're beastly things. Blackey has just

managed to break one in half. Porridge is sometimes

made of them, an empty shell-case comes in very handy for

grinding purposes, it is no use boiling these stone slabs

of nourishment as they will resist the effects of boiling

water for hours. The Turks gave us a little demonstration

last night, Blackey and I were trenching at the time in

the front trenches and were lucky enough to get a good

view of the proceedings. About half-past-eight the rifles

started to crack; there seemed to be a continuous rattle

from Walkers post right up to the lonesome pine. All the

positions here are named. On our left are the Pommies,

our post is called Mouri Par, following on comes Walkers,

a few hundred yards from us just across the gully, then

comes Popes, Quinns, Courteneys, Steels, and lastly the

lonesome pine. But as I have not actually been in a

charge or even helped man the trenches yet, I will leave

my description and impressions till later. Jock and

Blackey are very interested at present over a flea, which

-25-

has up to the present evaded all their attempts at catching.

At last they have him, a regular beauty about five

times the size of an ordinary pulex irritans, this chap

must be a pulex irritantissimus. Now Jock has discovered

another and Blackey drawls out, "Leave 'em alone, now you

have disturbed the whole blanky family." Fleas are

rather plentiful in this camp. Being awake in bed at

night one can feel them indulging in races up and down

one's legs and back. These are the men in our section,

Ted, Eric Blackwell, Jock Holland, and myself. I was

section leader till we arrived here, but as Jock had been

to New Guinea and had seen more service than I, it behoved

me to ask him to accept that responsibility. Blacky is

our chief character; he is rather bushified and very good-natured,

has a pipe in his mouth all day and smokes any

black vile stuff that goes by the name of tobacco. He

expresses ideas which are not favorable to womenfolk.

I will never forget the first time I met him, his legs are

thin and slightly bandy, and inclined to wobble a little

at the knees, not from weakness but just because they are

his and therefore different from the average. When I try

to imagine him in the future I see an old good-natured

face with a bushy black beard and a pair of bandy legs;

these are his main features. The position I seem to see

him in is strolling down George Street with about twenty

open-mouthed youngsters following in his wake, gazing at

the shop-windows. We have to shift quarters this afternoon,

-26-

our present lot of dug-outs are not satisfactory

from a sanitary point of view. Personally, I am very

glad for the shift, as we will be situated upon a terrace

cut out from the side of a hill overlooking the sea, I

always feel cramped and miserable shut away from an

open view; the rest of the section were very pleased

with this posse as it is called, till the roof threatened

a disastrous downpour upon our heads. The last two

nights we have been playing soldiers in reality, doing

patrol work in a deep gully looking for Turks, we creep

gingerly along picking along our steps over stones and

bushes, sitting down every few yards to listen. I will

describe last night's patrol work to give you an idea

what we do. To begin with an order has come out that no

shot is to be fired on the peninsular by our men for

forty-eight hours. The order came out yesterday morning

so all day long our guns were quiet, no shots rang out

from our snipers in answer to the Turks, no machine guns

rattled their death watch tick. Now and then the Turks

would fire but no return being offered their shooting

died down. Yesterday evening just about dusk our trench

partly fell in with the two patrols on the right, before

leaving Captain Wier told us all to be very careful and

vigilant as an attack by the Turks was expected, a

rumour having spread amongst them that we were evacuating.

As it happened our patrol party had the first shift, that

is from about half-past five till midnight. We crept over

the parapet just about dusk into the bed of a stony little

creek which runs up into the gully and then branches out

into two arms. The formation of the gully resembles a

crater somewhat, high clay walls surround it ri sing in

places to about two hundred feet, the only opening being

-27-

where this small watercourse breaks through to the sea;

cutting this water course at right angles are some of

our trenches; cutting this large hollow in half is a

steep ridge tapering down from the Turkish trenches

to the junction of the watercourse. Our usual programme

is to follow the bed of one creek up generally

the right then cut across and examine the left, but as

this was a special night we did otherwise. As soon as

we had got a little distance from our trenches I asked

Sergeant Riley what his plan of procedure was, but before

he could reply I asked might I make a suggestion. He is

a very nice fellow, as game and careful as he can be.

Of course he said yes I could, so this is what I proposed.

Our usual course is either up the bed of the

creek I said, or else through the more or less open bush;

on the left bank now the last few nights have been very

moonlight and in all probability the Turks have noted

this course, and should they intend making an attack the

first thing they will do will be to capture us to stop

the alarm being given. I propose that we cut through

this scrub on the right and take up a high position overlooking

a track which in all probability they would take

should they come down. The idea I have written down was

really the Sergeant's as he had really suggested the

posse on the right, but I will just write down here what

actually took place. My suggestion of cutting through

the scrub was followed, so we crept along the bank till

we came to what appeared to be a track. I gave my rifle

to the Sergeant while I crept up this, accompanied of

course by my little automatic pistol, to see if it

offered a chance of progress, it seemed to have been a

-28-

track once but appeared to have been abandoned to foxes.

I thought we could get along this so came back and

reported. Up we crept all of us all told, the Sergeant

and I in front, the other two about fifteen yards behind,

there was only room of course for one abreast; sometimes

we'd push through on our hands and knees, at others

just force through the thick wild holly and privet.

We had not got far before it began to get very dark, the

moon did not come up till nine o'clock and as it was

cloudy the darkness seemed to settle over everything and

take possession. Turning a sharp bend in this track

a rather pungent odour made its presence known, something

like an old dead sheep decayed just enough to let the

ribs appear. But no sheep had died here - lying along

the track all facing the same way were six dead Turks.

Their bones showing white in the fast fading light, their

uniforms tattered bits of rag about them. Here the track

seemed to end, and as it was too dark to proceed further

we had to crouch down amidst this ghastly company. Here

we had to sit for about two hours till the faint rays

of the coming moon helped us on our way. It is wonderful

how many noises are in the undergrowth at night, various

little night creatures were scratching among the dead

leaves; one took a visit to the dead Turks and took

sudden fright at my boot, at another time we heard something

coming up from the creek; swish, swish we heard

in the undergrowth just like a man's thighs brushing

against the leaves. My safety catch went forward and I

slipped the cut-off out of my rifle ready to bail up

Mister Turk should it happen to be he, but it must only

have been a fox jumping through the leaves. As soon as

-29-

the light began to show we pushed forward and arrived

at last at the Turkish outpost. We skirted this and wound

our way down the gully again. We did not go far down

however, we had satisfied ourselves that no Turks were

mobilising for an attack, so turned sharp to the right

crossing the ridge rather high up. By this time the

moon was well up in the sky, fleecy white clouds were

drifting across but peace was not over all, towards the

north flashes would appear in the sky looking from where

we were seated like sheet lighting. Then would follow

a great peal of thunder - boom! boom! it would sound

rumbling over the sea and up the gullies. Our battleships

were bombarding the Narrows. We investigated the

left hand gully, creeping up little watercourses that led

up towards our trenches looking for Turks that might

have crept down in the darkness and concealed themselves

for the purpose of throwing bombs. But Abdul kept very

serenely to his trenches last night and we returned to

ours just on the tick of twelve. Captain Wier seemed

rather pleased to see us. Lieutenant Harris told me

later that the Captain was very anxious lest we should be

cut off last night. I got a good souvenir the other day,

in fact it was on Mother's birthday. I was doing fatigue

work fixing up a wall near the cook house (squadron cooking

is starting in a few days) when something plucked

at my sleeve and buried itself with a splutter in the

clay in front of me. The something seemed to be a bullet

which passed through the right sleeve of my shirt. I

dug the bullet out, I was looking for a good one to bring

back and now I have it.

-30-

dm

dmThis transcription item is now locked to you for editing. To release the lock either Save your changes or Cancel.

This lock will be automatically released after 60 minutes of inactivity.